Borges Nonfiction

- At July 26, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

To refute him is to become contaminated with unreality.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “The Avatars of the Tortoise”

Borges Works: Nonfiction

This page profiles Borges’ major works of nonfiction, including several books only available in Spanish. The page is divided into two sections: “Core Works,” which represent Borges’ original essay collections, and “Compilations,” which include edited selections from his “core works” and other sources. In doing so, I have attempted to create a chronological narrative that highlights Borges’ development as an essayist. (I have, however, placed Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions as the first book profiled.) The following works are included:

Core Works

Inquisiciones (1925)

El tamaño de mi esperanza (1926)

El idioma de los argentinos (1928)

Evaristo Carriego (1930)

Discusión (1932)

Las kenningar (1933)

Historia de la eternidad (1936)

Otras inquisiciones / Other Inquisitions (1952)

Compilations

Selected Non-Fictions (1999)

Borges y el cine / Borges In/And/On Film (1974/1988)

Prólogos, con un prólogo de prólogos (1975)

On Argentina (2010)

On Mysticism (2010)

On Writing (2010)

Borges On Shakespeare (2018)

All book images include the Spanish first edition where appropriate; subsequent English translations are generally represented by their most “current” covers. Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com, unless it’s the original first edition, which just enlarges the image. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

Selected Non-Fictions / The Total Library

Selected Non-Fictions By Jorge Luis Borges Edited by Eliot Weinberger Viking, 1999 Online at: Internet Archive |

Selected Non-Fictions By Jorge Luis Borges Edited by Eliot Weinberger Penguin, 2000 |

The Total Library (Non-Fiction 1922–1986) By Jorge Luis Borges Edited by Eliot Weinberger Penguin, 2000/2007 |

In 1999 the literary world celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of Borges’ birth. This “Borges Centennial” was marked by numerous lectures, conferences, and artistic projects, from performances of Borges-themed tango to exhibitions of original manuscripts. One of the most anticipated events was Penguin-Viking’s publication of three massive volumes of Borges’ work, each dedicated to a different genre: his short stories, his non-fiction, and his poetry. It was the first time a single publisher had attempted to collect, curate, and translate the bulk of Borges’ impressive oeuvre, and it was justly celebrated as a watershed of Borges translation.

The third of these volumes was Selected Non-Fictions, which immediately won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. It was an honor well deserved. Until its publication, English translations of Borges’ essays were painfully rare. A few stray pieces appeared in Labyrinths, but the only genuine collection was Other Inquisitions, published in 1964 and occasionally criticized for its didactic translations.

It would be impossible to collect all of Borges’ nonfiction in a single volume; but editor Eliot Weinberger does an excellent job presenting a broad survey of his work, selecting 161 pieces from over twelve hundred “essays, prologues, book reviews, film reviews, transcribed lectures, capsule biographies, encyclopedia entries, historical surveys, and short notes on politics and culture.” Two-thirds of these pieces had never been translated into English, and the others were given fresh translations by Eliot Weinberger, Esther Allen, and Suzanne Jill Levine. Their work reveals a side of Borges previously unknown to many Americans, who primarily associate Borges with his intricate and sometimes challenging short fictions. Like the amiable professor next door, the Borges of Selected Non-Fictions makes a charming dinner guest, brimming with enthusiasm about countless subjects and delighted to converse with any guest. As Weinberger remarks in his excellent introduction:

Those for whom Borges is the archetype of the detached and cerebral metaphysician may be surprised… Borges, the blind old man of the popular image, was for years a movie critic. Borges, the recondite scholar, was a regular contributor to the Argentine equivalent of the Ladies’ Home Journal. He was equally at home with Schopenhauer or Ellery Queen, King Kong or the Kabbalists, Lady Murasaki or Erik the Red, Jack London, Plotinus, Orson Wells, Flaubert, the Buddha, or the Dionne Quints. More exactly, they were at home with him. Borges is both a deceptively self-effacing guide to the universe and the inventor of a universe that is a guide to Borges.

The pieces are arranged chronologically and occasionally grouped by the genre, such as “Capsule Biographies” or “Film Reviews.” The majority of Borges’ best-known essays are represented—“A History of Eternity,” “The Total Library,” “A New Refutation of Time,” “Kafka and his Precursors”—along with lesser-known gems such as his scathing dismissal of King Kong, a hatchet-piece directed at Lord Dunsany, and a review of Faulkner’s Absalom! Absalom! that doesn’t mention the book until the final three sentences.

The most fascinating discoveries are the “Prologues,” Borges’ introductions to the works of other writers. While a few are expected, such as Borges’ modest preface to his own translation of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and his introduction to Adolfo Bioy Casares’ novel, The Invention of Morel, the more obscure selections are the real standouts. His preface to Franz Kafka’s “The Vulture” is only five paragraphs long, but Borges delivers a cogent, no-nonsense appraisal of Kafka that’s all the more brilliant for its brevity and concision. Another pleasant surprise is his generous prologue to Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles:

In its character of anticipating a possible or probable future, [Kepler’s] Somnium Astonomicum prefigures, if I am not mistaken, the new narrative genre which the Americans of the North call “science fiction” or “scientifiction,” of which a notable example is these Chronicles… What has this man from Illinois created—I ask myself, closing the pages of his book—that his episodes of the conquest of another planet fill me with such terror and solitude?

Although Selected Non-Fictions has a few puzzling omissions, such as “Partial Magic in the Quixote,” “A Note on (toward) Bernard Shaw,” and Borges’ “Autobiographical Essay,” the collection could be twice as long and still barely scratch the surface. This is an essential book, and will please not just admirers of Borges, but anyone who delights in literature, journalism, metaphysics, and paradox.

The Total Library

In 2000 Allen Lane/Penguin issued Selected Non-Fictions in the UK as The Total Library (Non-Fiction 1922–1986). The paperback version came out in 2007, sporting a lovely cover taken from Sean Kernan’s The Secret Books. Although the “new” name suggests a larger anthology than “Selected Non-Fictions,” the contents of both books are identical. Readers looking to purchase a paperback version of Selected Non-Fictions may prefer The Total Library, simply because it has a much nicer cover!

Core Works

Inquisiciones

Inquisiciones By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Editorial Proa, 1925 Online at: Internet Archive |

Inquisiciones By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1998 |

In 1914, the First World War stranded the Borges family in Geneva, where Borges attended the Collège Calvin. After he graduated, the family moved to Spain. Finding a mentor in the Andalusian poet Rafael Cansinos Asséns, the young Borges was absorbed into the ultraístas, a literary circle devoted to cosmopolitan ideals and avant-garde poetry. During his time immersed in Spanish ultraísmo, Borges wrote two books of essays and poems, praising among other things pacifism, anarchy, and the Russian Revolution. Embarrassed by these youthful manifestos, Borges destroyed both books before leaving Europe in 1921.

Upon his return to Buenos Aires, Borges became part of a burgeoning avant-garde literary scene. He founded two magazines, Prisma and Proa, and published his first book of poetry, Fervor de Buenos Aires. Proa, or “Prow,” lasted eighteen issues across two iterations, and featured many of Borges’ essays, reviews, poems, and translations. Borges was also published in Nosotros, Inicial, Martín Fierro, and the Uruguayan magazine Alfar. In 1925, Borges collected the best of his essays under the title of Inquisiciones, a 160-page book published by Editorial Proa in a run of 500 copies.

The original edition of Inquisiciones included the twenty-eight essays listed below. Three pieces are included in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF], and three pieces are included in Penguin’s On Writing [OW].

- Prólogo

- Torres Villaroel

- La traducción de un incidente

- El “Ulises” de Joyce (“Joyce’s Ulysses”) [SNF, OW]

- Después de las imágenes (“After Images”) [SNF, OW]

- Sir Thomas Browne

- Menoscabo y grandeza de Quevedo

- Definición de Cansinos Asséns

- Ascasubi

- La criolledad en Ipuche

- Interpretación de Silva Valdés

- Examen de metáforas

- Norah Lange

- Prólogo de “La calle de la tarde”

- Buenos Aires

- “…abreviatura de mi libro de versos y la compuse el novecientos veintiuno.”

- La Nadería de la Personalidad (“The Nothingness of Personality”) [SNF]

- E. González Lanuza

- Acerca de Unamuno, Poeta

- La Encrucijada de Berkeley

- Acotaciones

- Manuel Maples Arce—Andamios interiors—México, 1922

- Ramón Gómez de la Serna (La sagrada cripta de Pombo)

- Omar Jayám y Fitz Gerald

- Queja de todo criollo.

- Herrera y Reissig

- Acerca del expresionismo: Alfred Vogts, Werner Hahn, Wilhelm Klemm [OW]

- Ejecución de tres palabras

- Advertencias

The majority of Borges’ “inquisitions” deal with the art and craft of writing, the Spanish literary tradition and its relationship to the Argentine avant-garde, and the challenges of translation. A few pieces celebrate local writers, such as Norah Lange, the subject of Borges’ unrequited romantic attention and the darling of the Florida group. A few non-Spanish authors are discussed, most notably Omar Khayyám, John Milton, Walt Whitman, Thomas Brown, and a trio of German poets grouped under the title “About Expressionism.”

One of the most enduring pieces in Inquisiciones is “El ‘Ulises’ de Joyce.” First published in Proa in January 1925, this essay offers Borges’ first thoughts on James Joyce, a writer who would fascinate Borges for the remainder of his life. Written three years after the publication of Ulysses, Borges’ comments are not only prescient, they suggest the same mixture of bafflement and awe experienced by many first-time readers of Ulysses even today:

Beside the new humor of his incongruities and amid his bawdyhouse banter is a macaronic prose and verse, he raises rigid structures of Latin rigor like the Egyptian’s speech to Moses. Joyce is bold as the prow of a ship, and as universal as a mariner’s compass. Ten years from now—his book having been explicated by more pious and persistent reviewers than myself—we will still enjoy him. Meanwhile, since I have not the ambition to take Ulysses to Neuquén and study it with quiet repose, I wish to make mine Lope de Vega’s respectful words regarding Góngora:

Be what may, I will always esteem and adore the divine genius of this Gentleman, taking from him what I understand with humility and admiring with veneration what I am unable to understand.

Although Inquisiciones was the first of Borges’ essay collections to survive his editorial wrath, Borges later disavowed its contents as “affected and dogmatic avant-garde exercises.” He refused to have Inquisiciones revised or reprinted, and was rumored to have purchased stray copies and consigned them to flames. The book does not appear in Obras completas, and has never been translated into English. Fortunately, Borges’ Spanish publisher Alianza reprinted Inquisiciones in 1998, and that version has become the most commonly read.

Additional Information

The translation of “El ‘Ulises’ de Joyce” quoted above is by Suzanne Jill Levine. Larry of Vaguely Borgesian posted a review of the Alianza Inquisiciones on his site, with a few translated passages.

El tamaño de mi esperanza

El tamaño de mi esperanza By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Editorial Proa, 1926 |

El tamaño de mi esperanza By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

The second iteration of Proa ceased publication in 1926, the same year Borges began writing for the newspaper La Prensa, which significantly broadened his audience. Later that year, Borges published his second collection of essays, “The Extent of My Hope.”

Collecting pieces that originally appeared in Nosotros, Proa, Inicial, Martín Fierro, La Prensa, and Valoraciones, the original edition of El tamaño de mi esperanza included the twenty-two essays listed below. Two pieces are included in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF], and three pieces are included in Penguin’s On Writing [OW].

- El tamaño de mi esperanza (“The Extent of My Hope”)

- El Fausto criollo

- La pampa y el suburbio son dioses

- Carriego y el sentido del arrabal (“Carriego and His Awareness of the City’s Outskirts”)

- La Tierra Cárdena

- El idioma infinito

- Palabrería para versos (“Verbiage for Poems”) [OW]

- La adjetivación

- Reverencia del árbol en la otra banda

- Historia de los ángeles (“A History of Angels”) [SNF]

- Las coplas acriolladas

- Acotaciones: El otro libro de Fernán Silva Valdés

- Oliverio Girondo – Calcomanías

- Las luminarias de Hanukah

- Saint Joan: a chronicle play

- Leopoldo Lugones – Romancero

- Ejercicio de análisis

- Milton y su condenación de la rima

- Examen de un soneto de Góngora

- La balada de la cárcel de Reading (The Ballad of Reading Gaol) [OW]

- Invectiva contra el arrabalero

- Profesión de fe (“A Profession of Literary Faith”) [SNF, OW]

As with Inquisiciones from the previous year, El tamaño de mi esperanza contains numerous ideas that would be developed more completely in Borges’ later work, from his notions about an infinite language to his uneasy fascination with Oscar Wilde’s “Ballad of Reading Gaol.” Having already established himself as a writer, Borges is more sure of himself in this second collection; but his earnestness occasionally approaches the humorless, particularly when he’s defending himself against critics:

I believe that words must be conquered, lived, and that the apparent publicity they receive from the dictionary is a falsehood. Nobody should dare write “outskirts” without having spent hours pacing their high sidewalks; without having desired and suffered as if they were a lover; without having felt their walls, their lots, their moons just around the corner from a general store, like a cornucopia… I have now conquered my poverty, recognizing among thousands the nine or ten words that get along with my soul; I have already written one book in order to write, perhaps, one page.

As the penultimate paragraph of “A Profession of Literary Faith,” the sentiment is salvaged from pomposity by that classic Borgesian hesitation, “perhaps.” While Borges would profess the same belief in the power of words throughout his life, it’s hard to imagine the mature philosopher using such imperious language as “nobody should dare” and “I have conquered” without a degree of irony. Borges’ widow María Kodama shares an amusing story about her husband’s discomfort about the collection in her introduction to the 1998 Alianza reissue:

One afternoon in 1971, after receiving his honorary doctorate in Oxford, while we were chatting with a group of admirers, someone spoke of El tamaño de mi esperanza. Borges reacted immediately, assuring her that the book didn’t exist, and he counseled her not to seek it any more. Next he changed the topic and he asked me to tell this genteel friend something more interesting; for example, our trip to Iceland. Everything seemed to remain there, but the following day a student called him on the telephone and said to him that the book was in the Bodleian Library, that he could remain tranquil before it existed. Borges, ending the conversation, with a smile said to me, “What are we going to do, María, I am lost!”

Borges refused to have El tamaño de mi esperanza revised or reprinted during his lifetime, and was rumored to have purchased stray copies and consigned them to flames. The book does not appear in Obras completas, and has never been translated into English. Fortunately, Borges’ Spanish publisher Alianza reprinted El tamaño de mi esperanza in 1998, and that version has become the most commonly read.

Additional Information

The translation of “Profesión de fe” quoted above is by Suzanne Jill Levine. The excerpt from María Kodama’s introduction was translated by Larry, the author of the Vaguely Borgesian blog, and comes from his review of El tamaño de mi esperanza, which features additional translated passages. “Carriego y el sentido del arrabal” appears in E.P. Dutton’s 1984 edition of Evaristo Carriego, translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni as “Carriego and His Awareness of the City’s Outskirts.”

El idioma de los argentinos

El idioma de los argentinos By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: M. Gleizer, 1928 |

El idioma de los argentinos By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1998 |

In 1928 Borges published his third book of essays, El idioma de los argentinos, or “The Language of the Argentines.” The following year, the collection won the Second Municipal Prize for Literature, which included a “lordly sum” of 3000 pesos. One of the things Borges bought with the prize money was the complete set of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Collecting pieces that originally appeared in Martín Fierro, La Prensa, Síntesis, and Criterio, the original edition of El idioma de los argentinos included the twenty essays listed below. Two pieces are included in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF] and Penguin’s On Writing [OW].

- Prólogo

- Indagación de la palabra (“An Investigation of the Word”) [SNF, OW]

- El truco

- Ubicación de Almafuerte

- La felicidad escrita

- Otra vez la metáfora

- El culteranismo

- Un soneto de Don Francisco de Quevedo

- La simulación de la imagen

- Las coplas de Jorge Manrique

- La fruición literaria (“Literary Pleasure”) [SNF, OW]

- Ascendencias del tango

- Para el centenario de Góngora

- Alfonso Reyes: Reloj de sol

- Ricardo E. Molinari

- Apunte férvido sobre las tres vidas de la milonga

- La conducta novelística de Cervantes

- Sentirse en muerte (“To Feel Oneself in Death”)

- Hombres pelearon

- Eduardo Wilde

- El idioma de los argentinos. (“The Language of the Argentines”)

Borges begins La idioma with a curiously detached preface:

No book is less in need of a prologue than this one, a lazy accumulation of prologues, a sediment of prologues, that is to say, inaugurations and first principles.

Its encyclopedic and monotonous air—Argentine hope, rough drafts of philological inclination, literary histories, hallucinations or lucid metaphysical finales, pleasures of memory, tricks of rhetoric—is more apparent than real. It is governed by three cardinal points. The first is a suspicion, language; the second is a mystery and a hope, eternity; the third is this flavor, Buenos Aires. The last two come together in the declaration entitled “To Feel Oneself in Death.” The first wants to watch over everything.

As with Inquisiciones and El tamaño de mi esperanza, the essays of El idioma de los argentinos feel somewhat labored, even affected, and one longs for the clarity, charm, and vaguely conspiratorial air of the mature Borges. Many of the ironies are unintentional, and it’s hard not to chuckle when a twenty-something Borges declares, long before he’s translated Faulkner or discovered Anglo-Saxon verse: “I must confess that…new readings do not enthrall me.” Still, a few beautiful passages emerge from the labyrinth of convoluted prose, and the essays contain many fascinating ideas destined for elaboration in later and more celebrated works. It is not difficult to glimpse the foundations of Tlön in “An Investigation of the Word,” and his discussions of Don Quixote feel like rehearsals for “Pierre Menard.”

And there are many discussions of the Quixote! Spanish literary tradition casts a long shadow over El idioma, particularly Cervantes, Quevedo, and Góngora. Each of these writers is granted an individual essay, but their verses are stitched throughout the collection, and Borges frequently invokes their work to examine the power, structure, and habits of language.

This is clearly demonstrated in one of the most accessible essays in the collection, “La fruición literaria,” appearing in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions as “Literary Pleasure.” Borges uses the essay to explore one of his favorite ideas, that the meaning and value of a literary passage are created by the reader, who engages with a text based on his own background, expectations, and assumptions about the source. Borges borrows the opening line from Cervantes’ sonnet “At the Tomb of King Philip II in Seville” to illustrate how “distance and antiquity” also play a role:

Time, such a respected subversive, so famous for its demolitions and Italic ruins, also constructs. Upon Cervantes’ lofty verse:

¡Vive Dios, que me espanta esta grandeza!

[By God, this greatness terrifies me!]

we see time refashioned and even notably widened. When the inventor and storyteller of Don Quixote wrote it, “vive Dios” was as ordinary an exclamation as “my goodness!” and “terrify” meant “astonish.” I suspect his contemporaries would have felt it to mean: “How this device astonishes me!” or something similar. Time—Cervantes’ friend—has sagely revised his drafts.

If time is here Cervantes’ editor, how much more will it serve Pierre Menard? More importantly, Borges’ point is intelligible to readers unfamiliar with Cervantes’ poem. One of the many virtues of Borges’ nonfiction, even these early “suppressed” essays, is Borges’ ability to engage the reader regardless of his subject. Whether discussing famous lines of verse, celebrating an obscure poet, or dissecting arcane systems of thought, Borges never makes his readers feel unintelligent or unprepared. While his subjects may be esoteric, Borges’ discussions are rarely hermetic. His subjects are spring-boards into broader explorations of language and metaphysics, conversations that invite the reader to draw their own conclusions.

An excellent example of this is “El culteranismo,” an examination of three common critiques directed against the poetry of Luis de Góngora. Most English readers are not overly familiar with Luis de Góngora or his rival Francisco de Quevedo, and have probably never heard of culteranismo, a Spanish baroque movement defined by Borges’ beloved Encyclopaedia Britannica as “an esoteric style of writing that attempted to elevate poetic language and themes by re-Latinizing them, using classical allusions, vocabulary, syntax, and word order.” However, no prior knowledge of culteranismo is required to appreciate the striking comparison that opens the essay:

If mathematics (a specialized system containing only a handful of signs, founded and governed strictly by reason) has its incomprehensibilities, and remains an object of perpetual discussion; how can we not obscure language, with its thousands of symbols, driven by something close to randomness?

Continuing, Borges presents language as a living organism subject to evolution and change. He positions the poet as central to this process: “Poetry—a conspiracy made by men of good will to honor being—favors the words it uses, regenerating them and almost reshaping them.” After dismissing claims that culteranismo abused metaphors and engaged in needless Latinisms, Borges proclaims:

We are now faced with the third mistake of culteranismo, the only one without remission and without pity, because in this small flaw we can glimpse death. I speak of his boundless mythological zeal, of his superstitious handling of Greek myths, or I should say the names in myths. It is as shamelessly lazy as “I swear to God!” from the mouth of an atheist, or the invocation “Cruz diablo!” spoken by one who believes in neither cross nor demon. Poetry is the discovery of myth, of intimate contact with myth, not taking advantage of exotic sounds and vanished realms. Culteranismo sinned: it fed on shadows, reflections, traces, words, echoes, absences, apparitions. He spoke—without believing in them—of the phoenix, of classical divinities, of angels. It was the garish image of poetry: it was adorned with deaths.

Intimacy with Luis de Góngora is not required to appreciate the poetic force of Borges’ accusation. Contemporary readers are free to make their own connections; as Borges would agree, relevance is created by the reader.

As with his first two essay collections, Borges refused to have El idioma de los argentinos revised or reprinted during his lifetime, and was rumored to have purchased stray copies and consigned them to flames. The only essay to escape his censure was “Sentirse en muerte,” or “To Feel Oneself in Death,” which was enrolled into Historia de la eternidad in 1936. El idioma de los argentinos does not appear in Obras completas, and has never been translated into English. Fortunately, Borges’ Spanish publisher Alianza reprinted El idioma in 1998, and that version has become the most commonly read.

Like Inquisiciones and El tamaño de mi esperanza, El idioma is long overdue for an English translation; unfortunately, Penguin tends towards conservatism, treating Obras completas as biblical authority and sometimes underestimating the English-speaking public.

Additional Information

The translation of the prologue is my own, but I leaned on the translation found in the Vaguely Borgesian blog’s review of the Alianza edition of El idioma de los argentinos. The review is worth reading, and contains several passages in English. The excerpts from “El culteranismo” were also translated by myself, albeit poorly. If anyone has a better translation, I’d appreciate it.

Evaristo Carriego

Evaristo Carriego By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: M. Gleizer, 1930 |

Evaristo Carriego [Revised and Expanded] By Jorge Luis Borges 1. Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1955 2. Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1965 |

Evaristo Carriego By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1998 |

Evaristo Carriego: A Book About Old-Time Buenos Aires

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation Norman Thomas di Giovanni

New York: E.P. Dutton, 1983

Shortly after Borges was born, his family relocated to Palermo, a suburb on the northeast outskirts of Buenos Aires along the bank of the Río de la Plata. Today, Palermo is a trendy neighborhood known for its high cost of living and myriad boutiques; but at the turn of the century, it was considered a vaguely seedy, lower-class barrio with a reputation for discordant politics and knife-wielding compadritos. By the time Borges entered his childhood, gentrification was well underway, and the neighborhood had lost some of its colorful character.

Still, Palermo enchanted young Borges with its legacy of cabarets and brothels, its tales of wanton women and violent men, desperadoes who danced the tango and enacted vengeance at the point of a knife. Borges absorbed the barrio’s outlaw heritage with the intensity of a boyish intellectual attracted to the dangerous and misbegotten. He eventually established a friendship with a local poet, his neighbor Evaristo Carriego. A reckless man who represented much of the “sentimental machismo” of Argentine tradition, Carriego soon became one of Borges’ early idols. Carriego died of tuberculosis in 1912, two years before the Borges family moved to Europe. They would come back to Buenos Aires in 1921, returning to a thriving city exploding with new ideas.

In 1930, Borges was flush with his first literary success. Having published three books of poetry and three collections of essays, he was a rising figure in the Argentine avant-garde, writing for numerous magazines and winning a national prize for El idioma de los argentinos. Despite being associated with the intellectual Florida group of writers, Borges spent much of his time immersed in the gaucho lore of his youth, wandering the slums, absorbing the local lunfardo dialect, and learning to dance the tango. This phase of his career culminated with the publication of Evaristo Carriego.

Ostensibly a biography of his boyhood hero, the book is a nostalgic paean to a vanished Buenos Aires, conjuring a mythic world of knife-fights and ringing with the sound of guitars and milongas. Published by M. Gleizer, the book was 118 pages long, featured two photographs by Horacio Cóppola, and sported an epigraph from de Quincey: “a mode of truth, not of truth coherent and central, but angular and splintered.”

The original edition of Evaristo Carriego included the seven chapters listed below. The English titles are from the Dutton edition.

- Declaración

- I. Palermo de Buenos Aires (“Palermo, Buenos Aires”)

- II. Una vida de Evaristo Carriego (“A Life of Evaristo Carriego”)

- III. Las misas herejes (“Heretic Masses”)

- IV. La canción del barrio (“The Song of the Neighborhood”)

- V. Un posible resumen (“Possible Summary”)

- VI. Páginas complementarias (“Complementary Pages”)

- I. Del segundo capítulo (“To Chapter II”)

- II. Del cuarto capítulo, “El truco” (“To Chapter IV, Truco”)

- VII. Las inscripciones de carro (“Inscriptions on Wagons”)

Evaristo Carriego was not successful, and as Borges matured, he viewed the book with an increasing amount of embarrassment. In 1955 he completed a revision for Emecé Editores, reducing some of its “excesses” but adding five more chapters:

- VIII. Historias de jinetes (“Stories of Horsemen”)

- IX. El puñal (“The Dagger”)

- X. Prólogo a una edición de las poesías completas de Evaristo Carriego (“Foreword to an Edition of the Complete Poems of Evaristo Carriego”)

- XI. Historia del tango (“A History of the Tango”)

- XII. Dos cartas (“Two Letters”)

A third and final edition came out in 1965. Featuring only minor revisions, it was this version that appeared in Obras completas.

Evaristo Carriego: A Book About Old-Time Buenos Aires

In 1983, E.P. Dutton published an English edition of Evaristo Carriego translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Titled Evaristo Carriego: A Book About Old-Time Buenos Aires, the book features an appendix with additional material related to Carriego, including an essay from El tamaño de mi esperanza entitled “Carriego and His Awareness of the City’s Outskirts,” the “Foreword to an Edition of the Selected Poems of Evaristo Carriego,” and a helpful “Notes” section. It also includes an informative introduction by Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Until Penguin adds Borges’ strange biography to their roster of twenty-first century translations, the Dutton edition remains the only Evaristo Carriego available in English.

Discusión

Discusión By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Gleizer, 1932 |

Discusión By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1957 Online at: Internet Archive |

Discusión By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1976 |

By the year 1930, Proa, Martín Fierro, and Inicial had ceased publication, and most of Borges’ writing was appearing in La Prensa. In 1931, Victoria Ocampo founded a new magazine named Sur, or “South.” Established with the support of Spanish writer and philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, Sur was loosely based on the Spanish magazine Revista de Occidente. Designed for a cosmopolitan readership and more serious in intent than Martín Fierro, Sur combined poetry, prose, politics, art, culture, and social commentary, and quickly became one of the most important voices in Argentine letters. Like many of his comrades from the avant-garde, Borges became a frequent contributor to Sur, and was a regular at the literary soirees held at Ocampo’s home. It was here that Borges met his lifelong friend and collaborator, Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Discusión is Borges’ fourth book of nonfiction, and collects essays and reviews that originally appeared in La Prensa, Sur, and the Spanish magazine El Sol. The original edition included the fourteen works listed below, many of which have appeared in English translations, including Labyrinths [L], Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF], and Penguin’s On Writing [OW].

- Prólogo

- La poesía gauchesca (“Gauchesco Poetry”)

- La penúltima version de la realidad (“The Penultimate Version of Reality”)

- La supersticiosa ética del lector (“The Superstitious Ethics of the Reader”) [SNF, OW]

- El otro Whitman (“The Other Whitman”)

- Una vindicación de la Cabala (“A Defense of the Kabbalah”) [SNF]

- Una vindicación del Falso Basílides (“A Defense of Basilides the False”) [SNF]

- La postulación de la realidad (“The Postulation of Reality”) [SNF]

- Films [SNF]

- El arte narrativo y la magia (“Narrative Art and Magic”) [SNF, OW]

- Paul Groussac

- Norah Lange

- La duración del infierno (“The Duration of Hell”) [SNF]

- Las versions Homéricas (“The Homeric Versions”) [SNF, OW]

- La perpetua carrera de Aquilies y la tortuga (“The Perpetual Race of Achilles and the Tortoise”) [SNF]

In 1957 Borges revised Discusión for Emecé Editores, dropping “Norah Lange” and including five additional essays and a handful of short pieces under the collective heading “Notas.”

- Nota sobre Walt Whitman (“A Note on Walt Whitman”)

- Avatares de la Tortuga (“Avatars of the Tortoise”) [L]

- Vindicación de “Bouvard y Pécuchet” (“A Defense of Bouvard and Pécuchet”) [SNF]

- Flaubert y su destino ejemplar (“Flaubert and His Exemplary Destiny”) [SNF, OW]

- El escritor argentino y la tradición (“The Argentine Writer and Tradition”) [L, SNF]

- Notas:

- H. G. Wells y sus parabolas [SNF]

- Edward Kasner and James Newman: Mathematics and the Imagination [SNF]

- Gerald Heard: Pain, Sex and Time

- Gilbert Waterhouse: A Short History of German Literature

- Leslie D. Weatherhead: After Death [SNF]

- M. Davidson: The Free Will Controversy

- Sobre el doblaje (“On Dubbing”) [SNF]

- El Dr. Jekyll y Edward Hyde, transformados. [SNF]

Discusión is the first collection of essays Borges allowed to remain in print, and it’s the first to appear in Obras completas. The book contains more reviews than his earlier collections, including film reviews and notes on cinema. Whether Borges was simply maturing as a writer, benefited from Ocampo’s influence, or a combination of the two, these essays are sharper and more focused than his work from the twenties. Less concerned with impressing the reader with his erudition and orotund prose, Borges writes directly to the point, conveying his ideas with a lighter touch and a fine appreciation of irony. Borges is also funnier, as may be seen in “A Defense of Basilides the False.” The subject of this essay is typically Borgesian—a long-forgotten Gnostic heresiarch. Borges narrates his discovery of this obscure figure with the conversational tone of someone describing how they gradually became a fan of the Grateful Dead:

In about 1905, I knew that the omniscient pages (A to All) of the first volume of Montaner and Simon’s Hispano-American Encyclopedic Dictionary contained a small and alarming drawing of a sort of king, with the profiled head of a rooster, a virile torso with open arms brandishing a shield and a whip, and the rest merely a coiled tail, which served as a throne. In about 1916, I read an obscure passage in Quevedo: “There was the accursed Basilides the heresiarch. There was Nicholas of Antioch, Carpocrates and Cerinthus and the infamous Ebion. Later came Valentinus, he who believed sea and silence to be the beginning of everything.” In about 1923, in Geneva, I came across some heresiological book in German, and I realized that the fateful drawing represented a certain miscellaneous god that was horribly worshiped by the very same Basilides. I also learned what desperate and admirable men the Gnostics were, and I began to study their passionate speculations.

Because who doesn’t stumble across these things in “some heresiological book in German?” Borges then presents Basilides’ central idea: our universe is a mere emanation, a shadow, of some primary Ideal universe. There are many such emanations, and tragically, we are the final and most imperfect of these; number 365 in a series of increasingly shabbier universes, each more sinful than the last. To escape this fallen state and reach the primordial Divinity, one must ascend through each universe in succession, earning one’s passage by reciting the secret names of its corresponding angels. There are 2555 of these “oral amulets,” only two of which have been retained by Gnostic philosophy—“Caulacau,” the “precious name of the redeemer,” and “Abraxas,” our own demiurge.

Borges concludes “Defense” with a sporting glimpse of an alternate reality where the Gnostics had not been ferreted out and destroyed: “Had Alexandria triumphed and not Rome, the bizarre and confused stories that I have summarized would be coherent, majestic, and ordinary.”

That Borges uses the word “stories” is telling. Earlier in the essay, Borges attributes his description of Basilides’ cosmogony to St. Irenaeus, an early bishop known for combating heresies. Borges explains, “I realize that many may doubt its accuracy, but I suspect this disorganized revision of musty dreams may in itself be a dream that never inhabited any dreamer.” Whether honest note of caution or subtle escape clause, this sentence casts the essay in a new light. Without direct access to Borges’ arcane sources, how much of “Defense” is history and how much is invention? If you replace the “I” of the essay with some obsessed scholar, or even the “fictional” Borges of Tlön, “A Defense of Basilides the False” reads like one of Borges’ ficciones, and very few readers would be able to distinguish the dream from the dreamer.

The two most famous essays in Discusión are both later additions: “The Avatars of the Tortoise” and “The Argentine Writer and Tradition.” Both were included in the 1962 collection Labyrinths, making them Borges’ first essays to reach the broader English-speaking world.

“The Avatars of the Tortoise” was written in 1939. A meditation on Zeno’s Paradox, one of Borges’ earliest obsessions, the essay begins with this wonderful passage: “There is a concept which corrupts and upsets all others. I refer not to Evil, whose limited realm is that of ethics; I refer to the infinite.” The essay continues cheerfully, even tongue-in-cheek, one idea playfully following another. Near the end, Borges offers a philosophical justification punctuated by his trademark dry humor:

It is venturesome to think that a coordination of words (philosophies are nothing more than that) can resemble the universe very much. It is also venturesome to think that of all these illustrious coordinations, one of them—at least in an infinitesimal way—does not resemble the universe a bit more than the others.

“The Argentine Writer and Tradition” is quite a different animal. Originally a lecture delivered to the Colegio Libre de Estudios Superiores in 1951, it appeared as an essay in Sur in 1955 and was added to Discusión in 1957. By the time Borges delivered this lecture, he had written Ficciones and El Aleph, was nationally recognized for his work in Crítica, El Hogar, and La Nación, and was widely known for his anti-Peronista politics. Unlike the other pieces in Discusión, “The Argentine Writer and Tradition” has overt political overtones, and is often identified as a precursor to postcolonial deconstructionism. A critique of the idea of a “national literature,” Borges deconstructs gauchesco poetry to expose its inherent artifice, and takes his own share of the blame for the “forgettable and forgotten” poems of his youth. Borges then eloquently refutes the notion that any specific culture must feel bound by tradition:

Furthermore, I do not know if it needs to be said that the idea that a literature must define itself by the differential traits of the country that produces it is a relatively new one, and the idea that writers must seek out subjects local to their countries is also new and arbitrary. Without going back any further, I think Racine would not have begun to understand anyone who would deny him his right to the title of French poet for having sought out Greek and Latin subjects. I think Shakespeare would have been astonished if anyone had tried to limit him to English subjects, and if anyone had told him that, as an Englishman, he had no right to write Hamlet, with its Scandinavian subject matter, or Macbeth, on a Scottish theme. The Argentine cult of local color is a recent European cult that nationalists should reject as a foreign import.

I wish to note another contradiction: the nationalists pretend to venerate the capacities of the Argentine mind but wish to limit the poetic exercise of that mind to a few humble local themes, as if we Argentines could only speak of neighborhoods and ranches and not of the universe.

Borges concludes his essay with a bold challenge and a solemn note of warning, an artistic declaration that resonates just as powerfully today as it did mid-century:

Therefore I repeat that we must not be afraid; we must believe that the universe is our birthright and try out every subject; we cannot confine ourselves to what is Argentine in order to be Argentine because either it is our inevitable destiny to be Argentine, in which case we will be Argentine whatever we do, or being Argentine is a mere affectation, a mask.

Additional Information

You can read the 1957 edition of Discusión in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF. Larry of Vaguely Borgesian posted a review of Discusión on his site, with a few translated passages. An interesting article that discusses “The Argentine Writer and Tradition” is “Borges, Politics, and the Postcolonial” by Gina Apostol for the Los Angeles Review of Books.

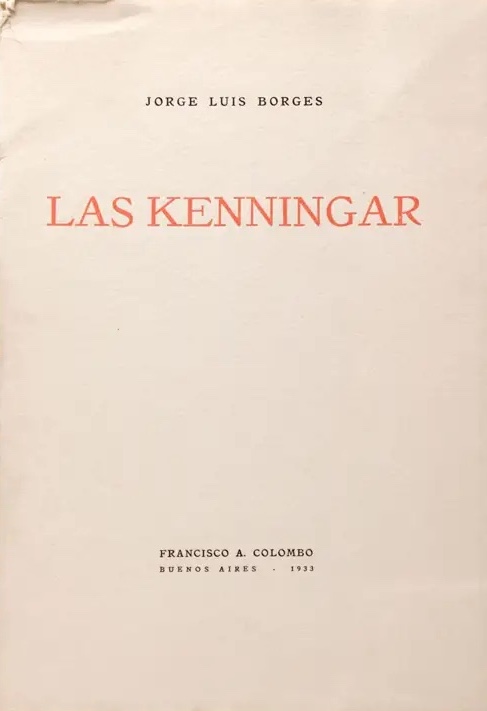

Las kenningar

Las kenningar

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Francisco A. Colombo, 1933

In the early 1930s Borges became fascinated with Nordic and Icelandic verse. Perhaps influenced by Norah Lange—who had recently written an essay on Snorri Sturluson for Azul—Borges published his own thoughts on Icelandic “kennings” in the Autumn 1932 issue of Sur under the title “Noticia de los kenningar.” A type of metaphor in which a poetic phrase is substituted for a common noun, typical kennings include “spear din” for battle, “battle sweat” for blood, and “whale road” for sea.

Considering Borges’ later obsession with Icelandic verse, it’s surprising this early encounter left the Argentine poet unmoved—he dismisses kennings as “formulaic” constructions devoid of the power to surprise. The essay concludes with a direct reference to Norah Lange and her Scandinavian heritage: “The dead ultraísta whose ghost continues to inhabit me always, delights in these games. I dedicate them to a bright companion of those heroic days, to Norah Lange, whose blood might perhaps recognize them.”

In 1933 Borges revised and expanded the essay as a slim book called Las kenningar. (He changed the gender from masculine to feminine to reflect Icelandic grammar.) In 1936 “Las kenningar” was reprinted in Historia de la eternidad; then further revised as “La poesía de los escaldos” (“The Poetry of the Skalds”) twenty years later for Antiguas literaturas germánicas. Borges used this opportunity to temper some of his youthful scorn.

Additional Information

Edel Porter discusses the history of this essay in “Noticia de los Kenningar: Borges, Kennings, and the Spanish Tradition,” published in the Old English Newsletter 47.1 (2021). M.J. Toswell published an English translation of “La poesía de los escaldos” for her translation of Ancient Germanic Literatures.

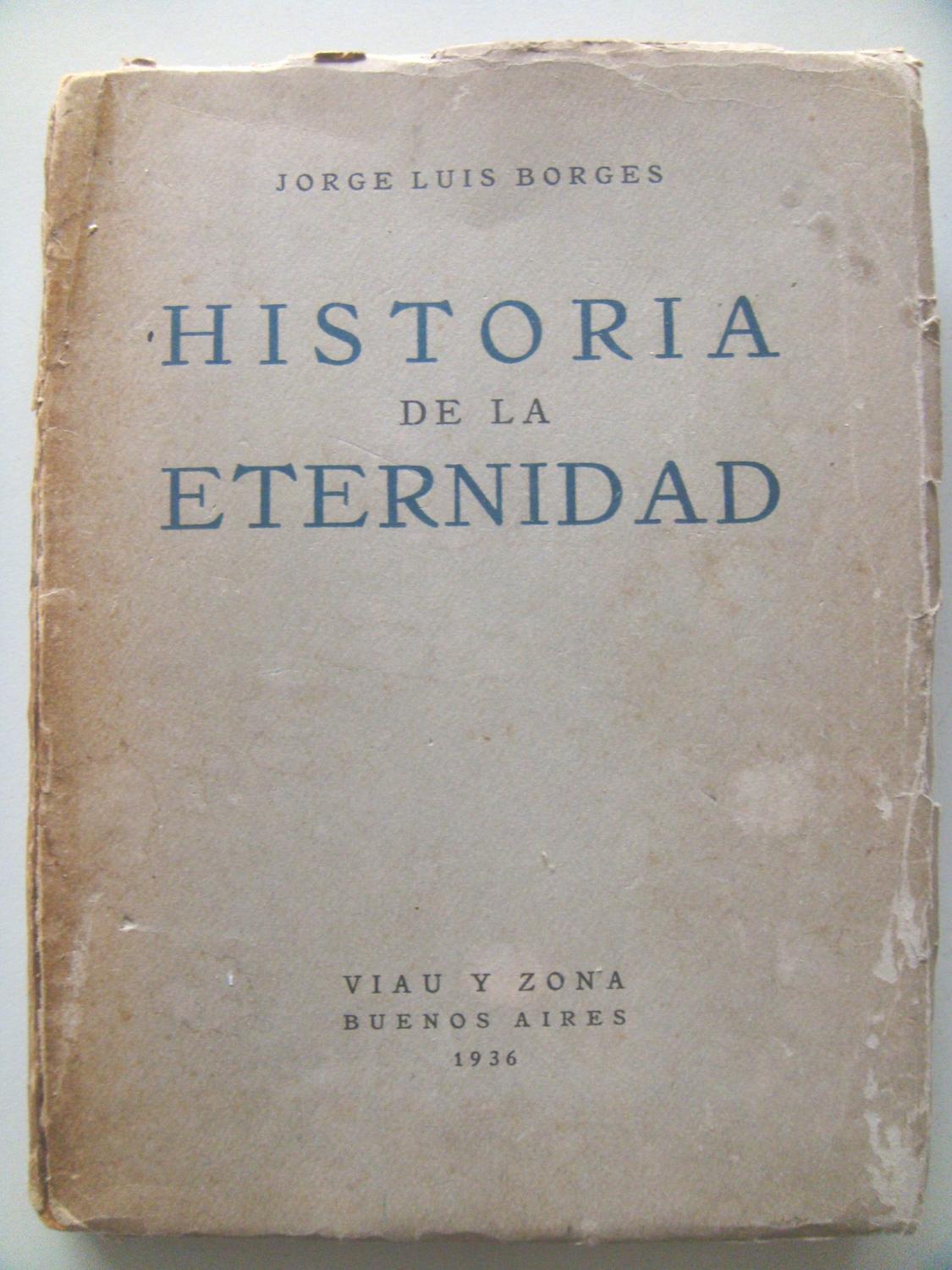

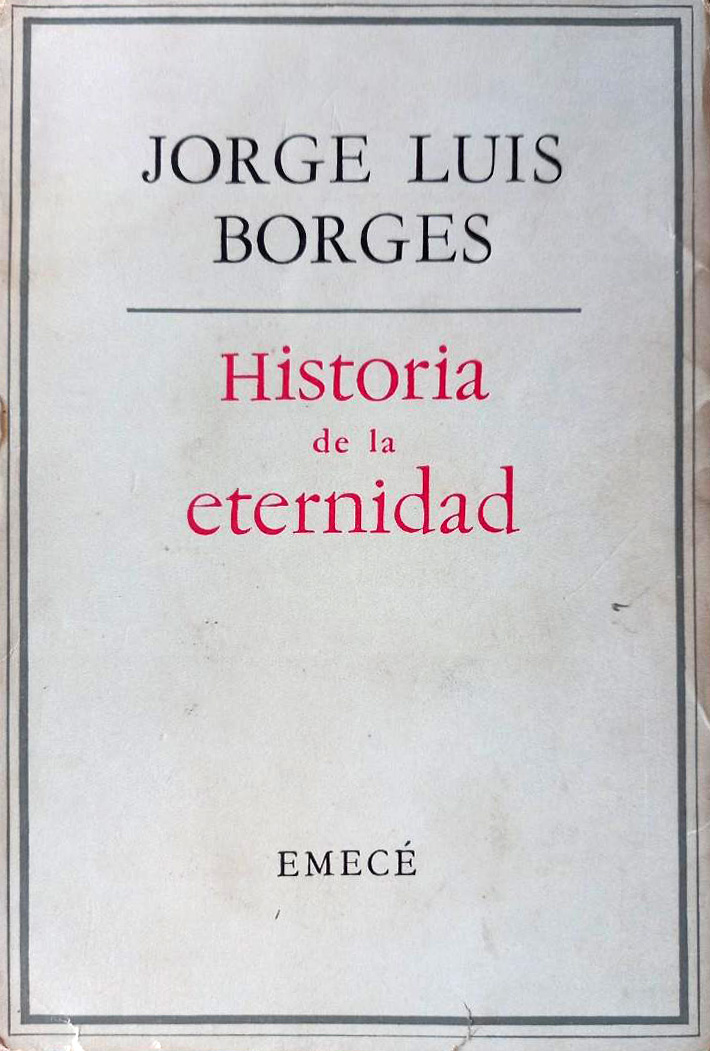

Historia de la eternidad

Historia de la eternidad By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Viau y Zona, 1936 |

Historia de la eternidad By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1953 Online at: Internet Archive |

Historia de la eternidad By Jorge Luis Borges Madrid: Alianza, 1971 |

In 1933, Borges accepted a position as co-editor of Crítica’s literary supplement, Revista Multicolor de los Sábados, or “Saturday Multicolor Magazine.” Charged with selecting its contents as well as contributing his own material, Borges published numerous pieces in Crítica, which had a circulation of 700,000 subscribers. These pieces included book reviews, biographical sketches, essays, and translations. Crítica also published Borges’ first works of fiction, including “Hombre de la esquina rosada” and the sketches that would comprise Historia universal de la infamia, or A Universal History of Infamy.

Historia de la eternidad collects lengthy essays that originally appeared in Sur and Crítica, many of which appear in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF] and Penguin’s On Writing [OW]. The original edition included the six works listed below:

- Historia de la eternidad (“A History of Eternity”) [SNF]

- Las kenningar (“The Kenningars.” Reprinted from the 1933 book.)

- La doctrina de los ciclos (“The Doctrine of Cycles”) [SNF]

- Los traductores de las mil y una noches (“The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights”) [SNF]

- Dos Notas:

- El acercamiento a Almotásim (“The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim.” Published here for the first time.)

- El arte de injuriar (“The Art of Verbal Abuse”) [SNF, OW]

In 1953 Borges revised Historia de la eternidad for Emecé Editores, adding a preface and including two additional essays:

- La metáfora (“Metaphor”) [OW]

- El tiempo circular (“Circular Time”) [SNF]

The collection takes its optimistic title from one of Borges’ most famous essays. Organized into four parts, “A History of Eternity” examines the concept of eternity as expressed in certain religious and philosophical traditions, the Enneads and the writings of St. Augustine in particular. The essay concludes with “Sentirse al muerte,” a reprint of a shorter piece originally published in La idioma de los argentinos. Variously translated as “Feeling in Death” or “To Feel Oneself in Death,” the piece describes Borges’ “personal theory of eternity.” Finding himself lost in an unfamiliar part of town during a twilight stroll, Borges has a sudden apprehension, a “true moment of ecstasy and the possible intimation of eternity.” He describes a feeling wherein the essential timelessness of the location allows his consciousness to dilate from the personal to the universal:

I write it out now: This pure representation of homogenous facts—the serenity of the night, the translucent little wall, the small-town scent of honeysuckle, the fundamental dirt—is not merely identical to what existed on that corner many years ago; it is, without superficial resemblances or repetitions, the same. When we can feel this oneness, time is a delusion which the indifference and inseparability of a moment from its apparent yesterday and from its apparent today suffice to disintegrate.

The number of such human moments is clearly not infinite. The elemental experiences—physical suffering and physical pleasure, falling asleep, listening to a piece of music, feeling great intensity or great apathy—are even more impersonal. I derive, in advance, this conclusion: life is too impoverished not to be immortal.

This “intimation” of eternity would reappear in Borges’ fiction, particularly “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” from Ficciones:

Nowadays, one of the churches of Tlön maintains platonically that such and such a pain, such and such a greenish-yellow colour, such and such a temperature, such and such a sound, etc., make up the only reality there is. All men, in the climactic instant of coitus, are the same man. All men who repeat one line of Shakespeare are William Shakespeare.

It has often been remarked that Borges’ essays contain the seeds of his fiction. Historia de la eternidad takes this a step further, and one of its best-known pieces is considerably more sapling than seed. Boldly presented as a book review, the subject of “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim” is a fictional detective novel named The Conversation with the Man Called Al-Mu’tasim: A Game of Shifting Mirrors, ostensibly written by an Indian lawyer named Mir Bahadur Ali. Borges’ “review” treats the book with deadpan legitimacy, and includes just enough facts and real-world specifics to be entirely plausible. Later referring to “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim” as “both a hoax and a pseudo-essay,” Borges claims that unknowing readers even attempted to order copies of Ali’s book!

“The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim” represents a turning point in Borges’ career. In his Infamia sketches for Crítica, Borges had begun to playfully embellish his sources, a trend first seen in essays such as “A Defense of Basilides.” In “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim,” however, Borges brazenly invents a subject, then places it under the same rigorous intellectual scrutiny reserved for his genuine critiques. Borges claimed that his literary inspirations were Carlyle and Butler, but this seamless blend of fact and fiction felt entirely new, and established a surreal sense of authenticity that would soon be labelled “Borgesian.” If the Infamia sketches are Borges tuning up his fictional orchestra, in “Al-Mu’tasim” the maestro steps onstage and taps his baton against the podium. His next short story would be “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” followed by “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.”

In 1941, “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim” was included in El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan, or “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a collection of eight short stories that forms the first half of Ficciones. In the prologue to El jardín, Borges wryly acknowledges the importance of his “hoax” as a creative breakthrough:

The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a resume, a commentary … More reasonable, more inept, more indolent, I have preferred to write notes upon imaginary books.

Additional Information

You can read the final edition of Historia de la eternidad in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF. Larry of Vaguely Borgesian posted a review of Historia de la eternidad on his site, with a few translated passages.

Otras inquisiciones

Other Inquisitions

Otras inquisiciones By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Sur, 1952 |

Otras inquisiciones By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1960 Online at: Internet Archive |

Other Inquisitions (1937-1952)

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Ruth L.C. Simms. Introduction by James E. Irby

Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964

Online at: Internet Archive

In 1936, the same year that Borges published La historia de eternidad, he accepted a part-time position as an editor for El Hogar, or “Home,” a respected ladies’ journal. In charge of a column called “Libros y authors extranjeros,” or “Foreign Books and Authors,” every two weeks Borges introduced his audience to an eclectic range of writers from Ellery Queen to Virginia Woolf. Writing in an accessible style, he nevertheless refused to underestimate his audience—one of his final pieces was a disparaging review of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake! After producing dozens of reviews, translations, and “capsule biographies,” Borges’ column concluded in 1939.

The following year, Borges had his first piece published in La Nación, “Some Opinions About Nietzsche,” followed by the poem “The Cyclical Night.” One of Latin America’s largest newspapers, La Nación was located on Florida Street and maintained a generally conservative approach to politics and culture. Borges would continue writing for the paper for the rest of his life, contributing everything from short stories to a 1979 obituary for his friend Victoria Ocampo.

Sixteen years would pass between La historia de eternidad and Borges’ next book of essays, Otras inquisiciones. His largest collection, Otras inquisiciones is also considered his finest, and gathers essays previously published in Sur, La Nación, and Los Anales de Buenos Aires, a small literary magazine that ran from 1946-1948. In 1964, Otras inquisiciones was published by the University of Texas Press as Other Inquisitions, which has the regrettable distinction of being the sole book of Borges’ essays granted a full English translation.

The contents of the original Otras inquisiciones are listed below, provided with the English titles found in Other Inquisitions, which does not include the “Inscripciones” section. The twenty-one essays found in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions are marked by [SNF], some of which were published under different English titles. Additionally, eight essays from Otras inquisiciones appear in New Direction’s Labyrinths, and are marked by [L].

- La muralla y los libros (“The Wall and the Books”) [L, SNF]

- La esfera de Pascal (“Pascal’s Sphere”) [L, SNF]

- La flor de Coleridge (“The Flower of Coleridge”) [SNF]

- El sueño de Coleridge (“The Dream of Coleridge”) [SNF]

- El tiempo y J. W. Dunne (“Time and J.W. Dunne”) [SNF]

- La creación y P. H. Goss (“The Creation and P.H. Gosse”) [SNF]

- Las alarmas del doctor Américo Castro (“Dr. Américo Castro Is Alarmed”)

- Nota sobre Carriego (“A Note on Carriego”)

- Nuestro pobre individualism (“Our Poor Individualism”) [SNF]

- Quevedo

- Magias parciales del Quijote (“Partial Enchantments of the Quixote”)[L]

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Nota sobre Walt Whitman (“Note on Walt Whitman”)

- Valéry como símbolo (“Valéry as a Symbol”) [L]

- El enigma de Edward Fitzgerald (“The Enigma of Edward FitzGerald”) [SNF]

- Sobre Oscar Wilde (“About Oscar Wilde”) [SNF]

- Sobre Chesterton (“About Chesterton”)

- El primer Well (“The First Wells”)

- El “Biathanatos” [SNF]

- Pascal

- El encuentro en un sueño (“The Meeting in a Dream”) [SNF]

- El idioma analítico de John Wilkins (“The Analytical Language of John Wilkins”) [SNF]

- Kafka y sus precursors (“Kafka and his Precursors”) [L, SNF, OW]

- Avatares de la Tortuga (“Avatars of the Tortoise”) [L]

- Del culto de los libros (“On the Cult of Books”) [SNF]

- El ruiseñor de Keats (“The Nightingale of Keats”)

- El espejo de los enigmas (“The Mirror of Enigmas”) [L]

- Dos libros (“Two Books”) [SNF]

- Anotación al 23 de agosto de 1944 (“A Comment on August 23, 1944”) [SNF]

- Sobre el “Vathek” de William Beckford (“About William Beckford’s Vathek”) [SNF]

- Sobre “The purple land” de Hudson (“About Hudson’s The Purple Land”)

- De alguien a nadie (“From Somebody to Nobody”) [SNF]

- Formas de una leyenda (“Forms of a Legend”) [SNF]

- De las alegorías a las novelas (“From Allegories to Novels”) [SNF]

- La inocencia de Layamón (“The Innocence of Layamon”) [SNF]

- Inscripciones:

- Dreamtigers

- Diálogo sobre un diálogo

- Las uñas

- Argumentum ornitologicum

- Nota sobre (hacia) Bernard Shaw (“A Note on (towards) Bernard Shaw”) [L]

- El pudor de la historia (“The Modesty of History”)

- Nueva refutación del tiempo (“New Refutation of Time”) [L, SNF]

- Epílogo (“Epilogue”)

In 1960, Borges revised Otras inquisiciones for the first edition of Obras completas. “Nota sobre Carriego,” “El encuentro en un sueño,” “La inocencia de Layamón,” were dropped, along with some of the material that was reprinted in El hacedor: “Dreamtigers,” “Diálogo sobre un diálogo,” “Los espejos velados,” and “Argumentum ornithologicum.” Only one new essay was added, “Historia de los ecos de un nombre,” translated as “A History of the Echoes of a Name” in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions.

Widely considered a masterpiece of nonfiction, Other Inquisitions reveals Borges at the peak of his powers. The collection is a delightful romp through his many interests, obsessions, and whimsies, from Cervantes to Zeno’s Paradox. Classical writers are compared, contrasted, and impishly correlated; time is refuted and subsequently reacquired; and metaphysical concepts are juggled with the grace of a chess master playing simultaneous games. Typical of the mature Borges, the reader is cheerfully invited to play along, and no matter the subject, his approach is animated by good humor and generous helpings of skepticism and self-doubt.

Other Inquisitions contains numerous celebrated essays, but even the lesser-known pieces have their moments, as demonstrated by Borges’ review of the English translation of Vathek, a gothic novel written in French but purported to have been translated from the Arabic. A charming read regardless of one’s familiarity with the novel, Borges’ paradoxical comment “the original is unfaithful to the translation” offers a Wildean epigram more memorable than Vathek itself.

Still, it’s the famous pieces that elevate Other Inquisitions above its predecessors, and the collection contains six or seven essays as highly regarded as anything in Ficciones. Two of these are “Kafka and His Precursors” and “A New Refutation of Time.” The first is a study of Kafka that concludes with a frequently-quoted remark about the anxiety of influence:

In the critic’s vocabulary, the word “precursor” is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotations of polemic or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.

The second is another exploration of time, one of Borges’ favorite subjects. However, unlike the youthful author of “Feeling Oneself on Death”—more famous as Part IV of “A History of Eternity”—the middle-aged Borges cannot afford the same intellectual distance, and the essay concludes with some of his most stirring lines:

And yet, and yet… Denying temporal succession, denying the self, denying the astronomical universe, are apparent desperations and secret consolations. Our destiny is not frightful by being unreal; it is frightful because it is irreversible and iron-clad. Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire. The world, unfortunately, is real; I, unfortunately, am Borges.

A tour de force of metaphysics, language, mathematics, and criticism, Other Inquisitions is an essential book, and belongs on the shelf of any serious reader.

Additional Information

You can read the final edition of Otras inquisiciones in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF.

Compilations

Borges y el cine (a.k.a. Borges en/y/sobre cine)

Borges In/And/On Film

Borges y el cine By Edgardo Cozarinsky Buenos Aires: Sur, 1974 |

Borges en/y/sobre cine By Edgardo Cozarinsky Editorial Fundamento, 1980 |

Borges In/And/On Film By Edgardo Cozarinsky Translation by Ronald Christ Lumen Books, 1988 Online at: Internet Archive |

Compiling all of Borges’ film reviews, Borges y el cine was published in 1974 by Edgardo Cozarinsky, an Argentine novelist, filmmaker, and film critic who was acquainted with Borges and Bioy Casares in the 1960s. The book was reissued as Borges en/y/sobre cine in 1980 by Editorial Fundamento; this version was translated into English by Ronald Christ and published as Borges In/And/On Film by Lumen Books in 1988. It has since been out of print. Along with Borges’ film reviews, Borges In/And/On Film includes a Borges-related filmography, two major essays by Cozarinsky, and the author’s reviews of cinematic Borges adaptations from from Diás de odio (1954) to Oraingoz Izen Gabe (1986). The Garden of Forking Paths has a full description and review of Borges In/And/On Film available on the “Borges Reviews” section.

Prólogos, con un prólogo de prólogos

Prólogos, con un prólogo de prólogos

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Torres Agüero, 1975

Online at: Internet Archive

Published in 1975, “Prologues, with a Prologue of Prologues” collects forty prologues Borges wrote between 1923–1974, from his early prologue for Norah Lange’s The Afternoon Street through such classics as Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

The contents of the Prologós are listed below:

- Prosa y poesía de Almafuerte

- Hilario Ascasubi: Paulino Lucero. Aniceto el Gallo. Santos Vega.

- Adolfo Bioy Casares: La invencíon de Morel (“The Invention of Morel”) [SNF, OW]

- Ray Bradbury: Crónicas marcianas (“The Martian Chronicles”) [SNF]

- Estanislao de Campo: Fausto

- Thomas Carlyle: Sartor Resartus

- Thomas Carlyle: De los herons (“On Heroes, Hero-worship and the Heroic in History”) Ralph Waldo Emerson: Hombres representativos (“Representative Men”) [SNF]

- Versos de Carriego

- Miguel de Cervantes: Novelas ejemplares

- Wilkie Collins: Le piedra lunar (“The Moonstone”) [OW]

- Santiago Dabove: Le muerte y su traje

- Macedonio Fernández

- El gaucho

- Alberto Gerchunoff: Retorno a Don Quijote

- Edward Gibbon: Páginas de historia y de autobiografía (“Pages of History and Autobiography”) (SNF)

- Roberto Godel: Nacimiento del fuego

- Carlos M. Grünberg: Mester de judería

- Francis Bret Harte: Bocetos californianos (“The Luck of Roaring Camp and Other Sketches”) [SNF]

- Pedro Henríquez Ureña: Obra crítica

- José Hernández: Martin Fierro

- Henry James: La humillación de los Northmore (“The Abasement of the Northmores”) [SNF, OW]

- Franz Kafka: La metamorfosis

- Nora Lange: La calle de la tarde

- Lewis Carroll: Obras

- El matrero

- Herman Melville: Bartleby (“Bartleby the Scrivener”) [SNF]

- Francisco de Quevedo: Prosa y verso

- Attilio Rossi: Buenos Aires en tinta china

- Domingo F. Sarmiento: Recuerdos de provincia

- Domingo F. Sarmiento: Facundo

- Marcel Schwob: La cruzada de los niños

- William Shakespeare: Macbeth

- William Shand: Ferment

- Olaf Stapledon: Hacedor de estrellas

- Emanuel Swedenborg: Mystical Works [SNF]

- Paul Valéry: El cementerio marino

- María Esther Vázquez: Los nombres de la muerte

- Walt Whitman: Hojas de hierba (“Leaves of Grass”) [SNF, OW]

A few of these prologues have appeared in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions [SNF] and Penguin’s On Writing [OW].

On Argentina

On Argentina

By Jorge Luis Borges

Edited by Suzanne Jill Levine and Alfred Mac Adam

Penguin Classics, 2010

Of Penguin’s three 2010 Borges compilations, On Argentina contains the most previously-untranslated pieces. I have not had the chance to review this book, so here’s the information from Penguin Classics:

Jorge Luis Borges wrote about Argentina as only someone passionate about his homeland can. On Argentina reveals the many facets of his passion in essays, poems, and stories through which he sought to bring Argentina forward on the world stage, and to do for Buenos Aires what James Joyce did for Dublin. In colorful pieces on the tango and the gaucho, on the card game truco, and on the criollos (immigrants from Spain) and compadritos (street-corner thugs), we gain insight not only into unique aspects of Argentine culture but also into the intellect and values of one of Latin America’s most influential writers. Featuring material available in English for the first time, this unprecedented collection is an invaluable literary and travel companion for devotees of both Borges and Argentina.

On Mysticism

On Mysticism

By Jorge Luis Borges

Edited by Suzanne Jill Levine and María Kodama. Introduction by María Kodama

Penguin Classics, 2010

A grab-bag of essays, poetry, and prose, most of the pieces compiled in On Mysticism originally appeared in Viking’s Collected Fictions, Selected Poems, and Selected Non-Fictions; only five are new translations. I have not had the chance to review this book, so here’s the information from Penguin Classics:

Jorge Luis Borges immersed himself and his readers in metaphysical fantasies—playing reason against faith, belief against logic. His profound knowledge of eastern religions was an endless source of inspiration for his writing. On Mysticism—edited by Borges’s widow, María Kodama—brings together a stunning group of prose pieces and poems that speak to this signature theme of his writing, from some of his most celebrated works to others that appear here in English for the first time. Together they yield valuable insights into the most ineffable dimension of his writing, illuminating the inimitable rewards of this literary visionary, a wisdom writer whose belief in the magic of words has made him beloved around the world.

On Writing

On Writing

By Jorge Luis Borges

Edited by Suzanne Jill Levine

Penguin Classics, 2010

Online at: Internet Archive

Of the thirty-eight pieces compiled in On Writing, twenty-eight were drawn from Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions; the rest are new translations or works that failed to make the original cut. Penguin offers this description:

Delve into the labyrinth of Jorge Luis Borges’s thoughts on the theory and practice of literature, and learn from one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century not only what a writer does but also what a writer is. For the first time ever, here is a volume that brings together Borges’s wide-ranging reflections on writers, on the canon, on the craft of fiction and poetry, and on translation—an ars poetica of one of the twentieth century’s greatest writers. Featuring many pieces appearing in English for the first time—including his groundbreaking early essay on magical realism, “Stories from Turkestan”—On Writing provides a map of both the changes and continuities in Borges’s aesthetic over the course of his life. It is an indispensable handbook for anyone hoping to master their own style or to witness Borges’s evolution as a writer.

The contents of On Writing are listed below. The essays found in Viking’s Selected Non-Fictions are marked by an asterisk (*).

I. Becoming a Man of Letters

-

- Ultra Manifesto

- On Expressionism

- After Images*

- Joyce’s Ulysses*

- The Ballad of Reading Goal

II. Word Music

-

- Verbiage for Poems*

- An Investigation of the Word*

- The Art of Verbal Abuse*

- On Literary Description*

- On Metaphor

- Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass*

III. On Translation

-

- Two Ways to Translate

- The Homeric Versions*

IV. Reading as Writing

-

- A Professional of Literary Faith*

- Literary Pleasure*

- The Superstitious Ethics of the Reader*

- The Paradox of Apollinaire*

- Kafka and His Precursors*

- Flaubert and His Exemplary Destiny*

V. The Critic at Work

-

- Virginia Woolf*

- T.S. Eliot*

- Paul Valéry*

- William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom!*

- Herman Melville, Bartleby the Scrivener*

- Henry James, The Abasement of the Northmores*

- Marcel Schwob, Imaginary Lives

- H.G. Wells, The Time Machine; The Invisible Man*

- Julio Cortázar, Stories*

VI. The Perfect Plot

-

- The Labyrinths of the Detective Story and Chesterton*

- Ellery Queen, Halfway House

- Adolfo Bioy Casares, The Invention of Morel*

- Wilkie Collins, The Moonstone

- The Detective Story*

VII. Narrative Art

-

- Stories from Turkestan

- The Cinematograph, The Biograph*

- Preface to the 1954 Edition of A Universal History of Infamy

- When Fiction Lives in Fiction*

All in all, it’s hard not to see On Writing as a cash-grab from Penguin. Since most of these essays appeared in Selected Non-Fiction, a committed reader is forced to pay full price for what amounts to ten brief outtakes—and it’s hard to see why pieces like “Ultra Manifesto,” “On Metaphor” and “Stories from Turkestan” weren’t included in the first place!

Borges on Shakespeare

Borges on Shakespeare

Edited and Translated by Grace Tiffany

ACMRS Press, 2018

Grace Tiffany is an American Shakespeare scholar known for writing historical novels. She has also been published on the Renaissance and Ben Johnson. Volume 543 of the Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, Tiffany’s Borges On Shakespeare was a labor of love, produced in cooperation with Penguin, The Folder Library, and the Borges Estate.

Publisher’s Description: Celebrated Argentine author Jorge Luís Borges found Shakespeare’s work so compelling that he not only fictively imagined the life of the playwright in two short stories, but also fashioned other stories and poems into adaptations of or meditations on Shakespeare’s plays, wrote essays about Shakespeare, and discussed him frequently in interviews,university lectures, and public talks. In this volume, Grace Tiffany gathers together all these varied writings and conversations. A critical edition, Borges on Shakespeare contains a lengthy introduction by its editor; annotated Borges stories, poems, essays, and transcribed talks (including his famous tales “Everything and Nothing” and “Shakespeare’s Memory”); essay contributions and one piece of fiction by Borges scholars; and a bibliography. Borges” “Shakespeare” material has heretofore been available to readers only in scattered sources. Combining them in one, Borges on Shakespeare directly addresses Borges’ lifelong engagement with Shakespeare, an author of tremendous significance to his own work and thought, and renders some Borges work sin English translation for the first time. Borges on Shakespeare will be useful to scholars of Shakespeare, Borges, and comparative literature and drama, as well as to the general reader who enjoys Shakespeare, Borges’ fiction, or both.

Additional Information

The author wrote an amusing post about her efforts to get this book published on her blog, Shakespeare In Fiction and Fact.

Borges Works

Main Page — Return to the Borges Works main page and index.

Fictions and Artifices — Short stories; the core Borges works.

Collaborations with Bioy Casares — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Collaborations with Others — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with others.

Poetry Compilations — Selections of Borges’ verse translated into English and published as compilations.

Poetry I — Early post-ultraísmo poetry, 1923 to 1943.

Poetry II — Mid-career collections from 1944 to 1969.

Poetry III — Late poetry books from 1969 to 1985.

Lectures, Conversations, and Interviews — Collections of Borges’ lectures, conversations, and interviews.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 9 August 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com