Review – Borges In/And/On Films

- At December 01, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

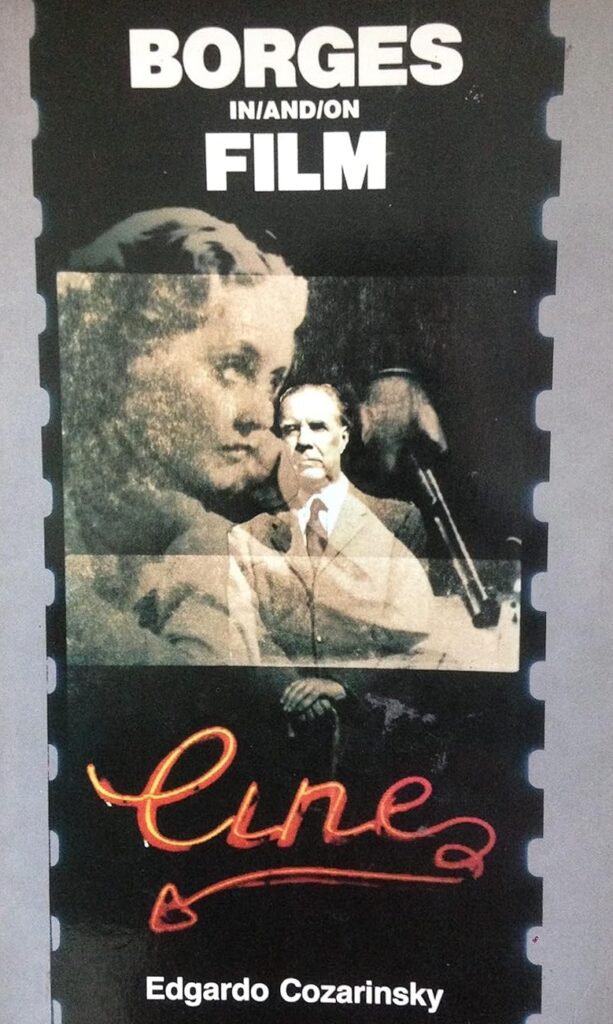

Borges In/And/On Film

Edgardo Cozarinsky

Translation by Ronald Christ

Lumen Books, 1988

We all know that a party, a palace, a great undertaking, a lunch for writers and journalists, an atmosphere of light-hearted and spontaneous camaraderie are essentially horrible. Citizen Kane is the first film that shows these things with some awareness of this truth.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “An Overwhelming Film,” 1941.

Edgardo Cozarinsky is an Argentine novelist, filmmaker, and film critic who was acquainted with Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares in the 1960s. In 1974, he published Borges y el cine. A popular book, it was translated into Italian in 1978 and into French the following year. In 1980 it was reprinted in Spanish with the title Cozarinsky had originally preferred, Borges en/y/sobre cinema, which was translated into English as Borges In/And/On Film in 1988. In each iteration of his book, Cozarinsky made revisions, alterations, and additions. He acknowledges the book’s confusing history in his preface: “I think Borges might have been pleased by the idea of a book whose different editions do not coincide, either in title or content.”

Beginning with a prologue written by Bioy Casares, Borges In/And/On Film is divided into four parts. The first is an essay written by Cozarinsky for the original Borges y el cine, “Partial Enchantments of the Narrative,” its title a play on Borges’ famous essay “Partial Magic in the Quixote.” An examination of Borges’ narrative tropes in the context of cinema, the essay is the most difficult piece in the book; which makes it a curious selection to greet the first-time reader. Cozarinsky is overly fond of academic jargon, obscure allusions, and the impenetrable neologisms of critical theory. Fortunately, these trappings of academia cannot conceal the pen of a novelist, and ultimately Cozarinsky wants to be understood by general readers as well as fellow critics. The essay rewards patience, and once a reader has untangled Cozarinsky’s run-on sentences and decoded the dense clusters of terminology, he proves to be a very subtle and nuanced thinker. His analysis of Borges’ famous “enumerations”—those startling and pleasurable lists that populate his work—is worth quoting at length:

Enumeration proposes to express the inexpressible; and, although it relies on only one scheme—enumeration—it is, like storytelling itself, syntactical in nature. In enumeration, the discontinuity of the actual text seems to be endowed with the prestige of representing absent, still greater text. By 1935, Borges’ enumerations in Universal History of Infamy reveal how they function as concealed illusionism: they display properties of narratives usually disguised in the very act of being employed. The terms in these enumerations—or the arguments united in a discourse—appear separated by what really connects them, as if by an electrical current: incongruity, paradox, simple otherness. At the same time, the enumerative combination as a whole registers the ironic richness of these clashes.

Although I am not convinced by his subsequent argument that Borges’ enumerations correspond to cinematic montage, Cozarinsky’s description is compelling, and the passage acquires a powerful poetic momentum of its own.

This opening essay is followed by a section called “Borges on Film.” The most extensive collection of Borges’ movie reviews available in English, this is the longest section in the book, and undoubtedly the main selling point for most readers. Originally published in Sur magazine from 1931-1945, these reviews encompass dozens of films, from classics such as The Petrified Forest and King Kong to lesser-known Argentine gems such as La Fuga. This section also contains Borges’ essay “On Dubbing,” the prologue to Los orilleros/El paraiso de los creyentes Borges wrote with Bioy Casares, and the pair’s Santiago collaborations, “Two Synopses of Films.”

Borges critiqued movies with the same erudition and enthusiasm he brought to his contemporary book reviews and author biographies, familiar to English-language readers from Selected Non-Fictions and other compilations. Much the way he might condemn a poem save for a felicitous turn of phrase, or praise a novel while singling out a particular image for scorn, Borges rarely discusses a film as a unified entity, but atomizes his critique scene by scene—“I want to stress one powerful touch,” or “two great scenes elevate the film” are formulations that appear often in these reviews. He is particularly sensitive to “unbelievable” characters, who “contaminate with unreality” the plausible characters around them. Also like his book reviews, these pieces are animated by paradox and wit. Borges hands out praise with reservation, but his barbs carry a Wildean sting—“Thus, in one of the noblest Soviet films, a battleship bombards the overloaded port of Odessa at close range, with no casualties except for some marble lions. This marksmanship is harmless because it comes from a virtuous, maximalist battleship.” Indeed, at times Borges is delightfully bitchy, such as his comment about Josef von Sternberg—“Formerly, he seemed mad, which at least is something; now, merely simple-minded”—or when he suggests that certain films demand “the burning down of the moviehouses where they play.”

In general, Borges disdains simplicity and sentimentality, prefers his villains to exhibit complex motivations, and appreciates bold cinematography. He is predictably sensitive to the differences between cinematic adaptations and their literary source material; however, Borges offers sincere praise when a director matches or even improves upon a book.

Of course, many of the films Borges discusses have been forgotten or rendered obscure by the passing years. Some readers may be reluctant to devote time to movies they’ve never seen and are unlikely to watch any time soon. Fortunately, Borges possesses the ability to make even the most arcane subject a matter of spirited debate. Whether one is familiar or not with the film being discussed, Borges’ writing sparkles, and his points proceed quickly from the specific to the general. A modern reader is likely to be surprised at how many of Borges’ comments still ring true—“I will not even mention the French: thus far their one and only desire has been not to resemble the Americans—a risk, I assure them, they do not run.” There are also enjoyable misfires. Perhaps the best-known piece in the collection, Borges’ review of Citizen Kane is remarkable for his insight into the film’s literary qualities; but also his woefully inaccurate prediction that Orson Welles’ film is one “no one especially wants to see again.”

The collected reviews are followed by a second Cozarinsky essay, “Film on Borges.” More accessible than the opening piece, “Film on Borges” offers a history of Borges’ influence on European cinema. The essay is organized into two parts. The first half, “A Source of Exegetes,” examines the development of Borgesian motifs in the French nouvelle vague. Bioy Casares’ novel The Invention of Morel is placed in relationship to Alain Robbe-Grillet and Last Year at Marienbad. Jacques Rivette’s Paris Nous Appartient (“Paris Belongs to Us”) is discussed at length, its various Borgesian strands teased out from an appearance of Other Inquisitions on the heroine’s nightstand. A brief study of Borges’ impact on Jean-Luc Godard leads to British and European cinema, and the second part of the essay, “A Source for Cinéastes” examines films produced after Borges was no longer an esoteric influence, but had become famous enough to warrant his own adjective, Borgesian:

The most obvious risk, however, in citing such illustrative examples is that of composing an inverted image of “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim;”—an incessant, interminable dispersion from a once secret source. Like the vestiges of Tlön in this world, the isolated appearance of Borges’s imprint establish a network among themselves; they impose an order, sanction a system.

Bernard Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem is briefly mentioned, but the majority of the discussion is devoted to Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s infamous 1970 film, Performance.

The final section is called “Versions and Perversions,” and features Cozarinsky’s notes and reviews of Borges adaptations from Diás de odio (1954) to Oraingoz Izen Gabe (1986). Cozarinsky’s reviews are engaging and informative, combining the insights of a filmmaker with the acumen of a professional critic. Like Borges, Cozarinsky is unconcerned whether an adaptation remains slavishly faithful to its source material, and praises films that honor the spirit of Borges while remaining true to the medium of cinema. For instance, Bertolucci’s The Spiders Stratagem and Leandro Katz’s Splits are both lauded, despite their significant departures from “The Theme of the Traitor and the Hero” and “Emma Zunz” respectively, while Alain Magrou’s faithful Emma Zunz is declared “utterly forgettable.” Of particular interest are Cozarinsky’s reviews of Invasión and Les Autres, the two films Hugo Santiago developed from synopses written by Borges and Bioy Casares. Cozarinsky rates both of these films quite highly, sharing Bioy Casares’ admiration rather than the disdain famously expressed by his partner. To be fair, Borges’ loathing of Santiago has never appeared entirely justifiable, and Cozarinsky’s well-argued defense of his films is significantly more compelling than Borges’ irascible rejection.

As useful as it may be, this final section is marred by a serious publishing error. The page devoted to Los orilleros and El muerto, a pair of 1975 “Westerns” based on Borges’ work, features the cast and crew of the films as expected. But instead of the correct reviews, they are followed by a non-sequitur—a few sentences describing a pair of Borges documentaries. It is an unfortunate oversight, as Los orilleros is the only adaptation based directly on a Borges script!

Edgardo Cozarinsky’s Borges In/And/On Film has been out of print for decades, and Lumen Books is no longer a going concern. Cozarinsky himself has expressed no interest in keeping the book current. His timing is especially regrettable, as one year after publishing this English translation, Cozarinsky made his own contribution to the canon of Borges cinema: Guerreros y cautivas, an adaptation of “The Story of the Warrior and the Captive.” Also missing are important later adaptations such as Los cuentos de Borges and Alex Cox’s Death and the Compass. Until someone decides to resurrect Borges In/And/On Film from the vault and give it the updated “Criterion treatment,” readers will have to be satisfied with used copies, which are inexpensive and easy to obtain.

Postscript

Until that time when Borges In/And/On Film is reissued, revised, or absorbed into an another book, The Garden of Forking Paths has taken the liberty of reprinting many of Cozarinsky’s reviews in the “Borges and Film” section. In fact, this entire section of the Garden was inspired by Cozarinsky’s book, and I’d like to thank Edgardo Cozarinsky and his translator Ronald Christ for blazing this trail. Now, if I could only get HBO to produce a high-end version of Ficciones…

Additional Information

Borges In/And/On Film

You may purchase a used copy of Cozarinsky’s book from Amazon.com.

Borges and Film

This section of the Garden of Forking Paths profiles every major film based on Borges and his works.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 12 August 2024

Main Reviews Page: Reviews

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com