Chapter 4: Galápagos Islands – Background

- At July 29, 2023

- By Great Quail

- In White Leviathan

0

0

Take five-and-twenty heaps of cinders dumped here and there in an outside city lot, imagine some of them magnified into mountains, and the vacant lot the sea, and you will have a fit idea of the general aspect of the Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles. A group rather of extinct volcanoes than of isles, looking much as the world at large might after a penal conflagration… Cut by the Equator, they know not autumn, and they know not spring; while, already reduced to the lees of fire, ruin itself can work little more upon them. The showers refresh the deserts, but in these isles rain never falls. Like split Syrian gourds left withering in the sun, they are cracked by an everlasting drought beneath a torrid sky. “Have mercy upon me,” the wailing spirit of the Encantadas seems to cry, “and send Lazarus that he may dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, for I am tormented in this flame.”

—Herman Melville, The Encantadas

Keeper’s Information & Background

Six hundred miles west along the equator from Ecuador, the Galápagos Islands are a chain of unique islands famous for their unusual climate and broad diversity of wildlife. Loosely governed by Ecuador since 1832, the islands are also known as “Los Encantadas,” or “The Enchanted Isles.” The epithet is not as piquant as it seems. The islands are considered enchanted because they sometimes appear to change location, the result of contradictory currents and unpredictable wind patterns that make navigation surprisingly difficult. For this reason they’re also called “The Wandering Isles.”

A) Brief History of Exploration, 1535-1845

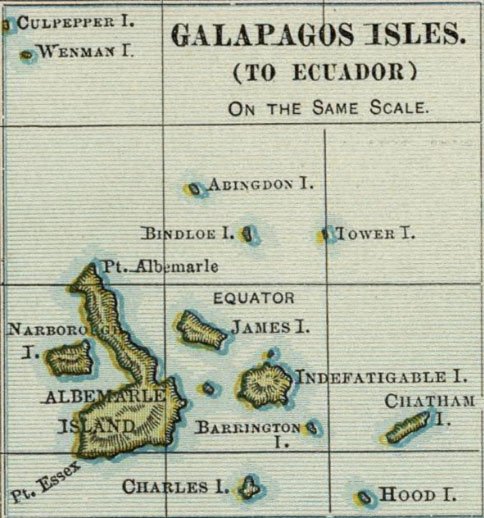

The first sailors to make note of the Galápagos were the Spanish, who discovered the uninhabited archipelago in 1535. Difficult to navigate and containing little water, the islands were more or less ignored, and early maps depict them in broad strokes. For the next two centuries, the main patrons of the islands were English buccaneers, who used them as a haven when pillaging Spanish treasure fleets. The first somewhat accurate map of the archipelago was made by the privateer William Ambrose Cowley in 1684. It was Captain Cowley who gave most of the islands their English names. Cowley’s map was refined in 1793 by Captain James Colnett of the British Navy, who explored the archipelago and suggested it could serve as a way-station for British whalers.

In 1818 the Globe of Nantucket discovered the waters around the islands were filled with sperm whales, and for the next few decades American whalers began using the islands to gather wood and tortoises. In 1831 the islands were claimed by the newly-minted Republic of Ecuador, who dispatched General José María de Villamil to settle them with colonists. While most of the old Spanish names were retained, Villamil and his companions renamed some islands in honor of South American war heroes.

Of course, the most famous visitor to the Galápagos Islands was the British naturalist Charles Darwin, who explored the islands in 1835 during the second expedition of the HMS Beagle. Darwin published Journals and Remarks in 1839. Commonly called The Voyage of the Beagle, the book describes his round-the-world journey with Captain FitzRoy, and contained geological and biographical descriptions of Charles Island, James Island, and Albemarle Island. Darwin would eventually use some of his observations to support his theory of natural selection, publishing On the Origin of Species in 1859.

The Islands in 1845

In 1845, the Galápagos Islands remain largely uninhabited. Although the archipelago is nominally a province of Ecuador, most British and American sailors consider this little more than an opportunistic boast, and treat the islands as neutral grounds. Yankee sailors use the English names, although a few have started calling Charles Island “Floreana” on account of the Spanish colony established by General Villamil.

B) Geography

The Galápagos Archipelago is composed of hundreds of islands, most of them too small to be recorded on contemporary maps. Only a dozen islands merit serious consideration, and the largest—Albemarle/Isabela—could contain the rest of the archipelago.

Galápagos Islands, 1897

Today the islands are properly referred to by their Spanish names. Because this scenario is set upon a Yankee whaler in 1845, it generally uses the English names, as would the crew of the Quiddity. To avoid confusion with modern maps, here are the English and corresponding Spanish names of the islands mentioned in this scenario, listed in order of decreasing size:

| English Name | Spanish Name |

| Albemarle Island | Isla Isabela |

| Indefatigable Island | Isla Santa Cruz |

| Narborough Island | Isla Fernandina |

| James Island | Isla Santiago |

| Chatham Island | Isla San Cristóbal |

| Charles Island | Isla Floreana |

| Hood Island | Isla Española |

| Barrington Island | Isla Santa Fé |

| Duncan Island | Isla Pinzón |

| Gardner Island | Isla Gardner |

C) Geology & Climate

The product of a geological hot-spot located between two tectonic plates, the Galápagos Islands sprawl over 330 miles of equatorial ocean. All of the islands were created by volcanic activity, but only the western islands are still active. The eastern islands are mostly extinct volcanoes, destined to be eroded into the sea and forgotten. Indeed, numerous once-visible islands are now entombed by waves, silent sentinels marching to oblivion on the lonely seafloor. Many of the western volcanoes are topped by calderas, bowl-like craters filled with solidified lava, or sometimes water. Occasionally lava erupts from these heights, but usually the most dramatic event in a caldera is a partial collapse.

Despite their location, the Galápagos Islands have a very different climate than most tropical islands. While the relentless, equatorial sun pounds the black anvil of the volcanic rocks, the shores of the islands are cooled by an Antarctic current, preventing the temperature from rising much above 90°F. This differential produces the islands’ famous cloud cover, a low ceiling of vapor wreathing the tops of the mountains but rarely producing rain. This combination of moist top and dry bottom gives the islands a distinct ecology, with damp vegetation found in the heights, and saltbush, cacti, and palo santo trees sprawled across the arid lowlands. While the shores are relieved by the odd mango grove, anyone expecting an abundance of rainfall and palm trees will be sorely disappointed!

Sunrise & Sunset

Being located along the equator, there’s very little seasonal variation in Galápagos. The sun generally rises around 6:00 am and sets around 6:00 pm, giving day and night an equal length of twelve hours.

D) The Yankee Perspective

Modern travelers see the Galápagos Islands as a magical place, a lost world of volcanic landscapes teeming with exotic wildlife. An expensive tourist destination, the islands never want for travelers seeking the perfect photograph of a blue-footed booby, a manta ray, or a cluster of black iguanas. It may come as a surprise, but nineteenth-century sailors have a more dour view of the “Galleypaguses.” Although not without their beauty, the islands are seen as forbidding and inhospitable. Crawling with huge spiders and weird reptiles, the islands’ rainless shores and saline lakes provide little relief from the equatorial sun. There are precious few lagoons, cocoa-nuts and bananas are in short supply, and the only women are the criminal deportees of Floreana’s penal colony. Fresh water must be sought far inland, and gathering firewood is considered a loathsome task—it’s invariably infested with centipedes and scorpions.

E) The Galápagos Tortoise

…there is something strangely self-condemned in the appearance of these creatures. Lasting sorrow and penal hopelessness are in no animal form so suppliantly expressed as in theirs; while the thought of their wonderful longevity does not fail to enhance the impression. Nay, such is the vividness of my memory, or the magic of my fancy, that I know not whether I am not the occasional victim of optical delusion concerning the Gallipagos. For, often in scenes of social merriment, and especially at revels held by candlelight in old-fashioned mansions, so that shadows are thrown into the further recesses of an angular and spacious room, making them put on a look of haunted undergrowth of lonely woods, I have drawn the attention of my comrades by my fixed gaze and sudden change of air, as I have seemed to see, slowly emerging from those imagined solitudes, and heavily crawling along the floor, the ghost of a gigantic tortoise, with “Memento * * * * *” burning in live letters upon his back.

—Herman Melville, “The Encantadas”

The Galápagos Archipelago takes its name from its most famous inhabitants. Tortoises reminded early visitors of saddles, so they were called galápagos, and old Spanish word for “saddle.” Numerous species of tortoise live on the islands, some possessing life spans well over a century. Painfully slow and abysmally stupid, the creatures have been hunted to the edge of extinction by several generations of hungry whalemen. Wild dogs, pigs, and sheep have also contributed to their decline in numbers, whether destroying their habitats or devouring their eggs. Thirty years ago a ship could bag hundreds of the tasty creatures; but by 1845, a few dozen is considered a good haul.

Memento Mori

From Darwin to Melville to Coulter, contemporary explorers frequently remarked on the unsettling demeanor of the Galápagos tortoise—its antediluvian features, the horror of its shaggy, ponderous crawl, or the satanic cast to its hooded face. Indeed, a curious superstition exists among seamen regarding tortoises. It’s said that certain wicked officers, especially captains, are transformed at death into one of these sluggish creatures. A few go even further, suggesting that particularly evil commodores may undergo this vile transformation while still among the living!

F) Turpining

Sailors erroneous refer to tortoises as terrapins, or just “turpins.” Hunting tortoises is called “turpining.” Turpining is a difficult and odious task, a chore universally hated by sailors from greenhorns to old tars. Following tracks worn into the rock, the men stalk the creatures inland. When they find a tortoise of manageable size, they flip it on its back and place rocks on its chest, which prevents the creature from retracting its legs. Slinging a canvas harness around the tortoise, its feet are used as lash-points. Often weighing between 50-75 pounds, the struggling creature is hefted onto a sailor’s back and carried to the ship, usually across volcanic rocks under a burning sun. This method is called “backing down” the turpin. Larger creatures are strapped to a pair of whaleboat oars and carried by two or more men. If a tortoise is caught near shore, it’s often flipped onto its back and dragged with leather straps or ropes fastened to its legs. Creatures too large to transport may be butchered on the spot.

One of the reasons tortoises are so valuable is their sheer hardiness. Stacked in the hold like so many living casks, tortoises can survive up to a year without food and water! When it’s finally time to cook the animal, it’s retrieved from storage and allowed a few days of freedom to “savor the meat.” Starved and thirsty, these poor reptiles roam the decks, pathetically licking everything in sight. They’re also quite stubborn in their general stupidity—it’s not unknown for a tortoise to bang its head against an unmovable mast and continue to plow forward, paddling is feet uselessly for hours. Needless to say, the sailors consider this all good fun.

Tortoises are usually made into soup, but large ones provide the officers with hearty steaks. The fat is considered especially succulent, as are the liver and bone marrow. Tortoise eggs are widely considered delicious. The creature’s fat may be rendered into oil, which is used for cooking and medicine—sailors believe that terrapin oil works wonders on digestion, prevents cramping, and loosens stiff joints. Finally, the creature’s shell and calipee may be fashioned into soup tureens and salvers.

Mythos Connection & The Lowell Expedition

The Galápagos Islands are where the player characters first come face-to-face with K’th-thyalei civilization. Although the islands themselves are only 5 million years old, their location has Mythos connections which extend to the Eocene Epoch.

A) Thal’n’lai

Some 50 million years ago, a different group of islands occupied the location of the Galápagos Archipelago. Most of these islands are now part of the sea floor, but once they were populated by the K’th-thyalei, who built several advanced structures in the region. The largest of these was Thal’n’lai a-Bha’nahf Yeth, unpoetically translated as “Sea Temple/Elder Thing Prison/Lab Nineteen.” The primary purpose of Thal’n’lai was to study a captive Elder Thing. (See “Background Part 1—History of Dagon.”) Things didn’t go quite as planned, and the Cataclysm brought the end of the Ancestors and their machinations. Thal’n’lai fell into disrepair and languished, lost to time at the bottom of the ocean floor.

B) Y’ha-n’thal

In 3600 BCE, the Deep Ones began studying the mantle plume that created the Galápagos Archipelago. The constructed a laboratory along the seafloor and carved several smaller facilities into the islands themselves, including a sizable outpost inside Volcán Wolf. These structures were connected by a series of Gates controlled from the main laboratory. When they finally coordinated the Gates, they made an unexpected discovery—there was an extra Gate, an ancient artifact that had plugged itself seamlessly into their network! The Deep Ones passed through this mysterious portal and discovered the Great Hall of Thal’n’lai. And there was the captive Elder Thing—half dead and insane, but still a source of inestimable knowledge. Like their Ancestors before them, they eagerly plucked the forbidden fruit.

Unfortunately, the Deep One’s discovery coincided with the end of their “Pacific Golden Age.” Corrupted by decadence, saddled by superstition, and riven by civil war, Deep One culture was already in decline. Over the next thousand years, science became magic, and magic became religion. The tectonic laboratories were abandoned and left to ruin. By 2600 BCE, only the outpost in Volcán Wolf remained. Its Gate now tuned solely to Thal’n’lai, the former laboratory had become a temple: Y’ha-n’thal, slavishly devoted to worshipping the Ancestors. The temple was inhabited by a degenerate cult of Deep Ones who viewed exposure to the Elder Thing as a holy sacrament, each trip to the communicant’s tank accelerating the breakdown of their collective sanity. (For its own part, the Elder Thing was unable to possess a Deep One mind. The best it could do was to keep the Gate open, which at least prevented complete entombment.) In 2112 BCE, a series of volcanic eruptions collapsed the aquatic dormitories and flooded Y’ha-n’thal with magma. The Deep Ones were boiled alive like a pot of frogs. The survivors slithered away and joined the new cults of Father Dagon and Mother Hydra. Eventually Y’ha-n’thal was forgotten—until discovered by Dr. Montgomery St. John Lowell.

C) Professor Lowell and the Encantadas

In 1829, the naturalist Montgomery Lowell signed onto the British whaler Atlantis, trading his skills as surgeon for the chance to observe the great Leviathan first-hand. Commanded by Hamilton Wolf, the Atlantis would take the Professor whaling for a year, then deposit Lowell in Hawaii so he could return on a homebound vessel. Ten months into the voyage, a freak squall capsized the Atlantis near Duncan Island, an extinct shield volcano halfway between Albemarle Island and Indefatigable Island. Over a dozen men perished in the shipwreck, including Captain Wolf. Salvaging a pair of whaleboats, the survivors reached Albemarle Island and settled at Banks Cove. Surely they’d be rescued soon?

Lowell quickly became obsessed with the island’s peculiar wildlife and tantalizing geology. One morning he set out to explore the northern volcano. Knowing the men would not appreciate his absence if a ship were sighted, he brazenly lied about his destination. His only companion was Rafael Castro. A Spanish sailor the Atlantis had acquired in Callao, Castro was a talented sketch artist and amateur geographer. In fact, it was Castro who suggested naming the northern volcano in honor of their departed captain, and so “Volcán Wolf” was marked on their map.

The Discovery

After a day exploring the volcano’s caldera, Lowell and Castro discovered a large cave in the shape of a hemisphere. A pit in the center of the cavern contained some strange jewelry and a stylus lathed from an unknown alloy. A passage at the end of the cavern led to something even stranger—a stone door locked by a curiously advanced mechanism based on a zodiacal progression. It only took Lowell a few hours to unlock the “Zodiac Door,” which brought him to the temple of Y’ha-n’thal and the Gate. The Gate proved more difficult to open than the door, but a restless night of surreal dreams gave him the answer, and he croaked his way into Thal’n’lai.

And there, Professor Lowell discovered the Elder Thing. Imprisoned in its tank since the Eocene Epoch, the creature was hopelessly damaged: its body was rotting into the nutrient fluids, and 50 million years of isolation had driven it insane. But nevertheless, it saw an opportunity in this strange mammalian scientist. If only this curious monkey could be convinced to enter the adjacent tank, the Elder Thing could begin the long process of domination and possession. It would finally have a servant—and maybe even a new body. It could finally escape.

Lowell didn’t need convincing. He crawled into the “communicant’s tank” without hesitation. And the Elder Thing showed him the universe.

What happened afterward is hazy. Using the stylus from the oubliette, Lowell began recording his revelations on the walls of the caldera cave. Prolonged exposure to the alien consciousness had a deleterious effect on his sanity, and he found himself entering amnesiac fugues, losing hours at a time. Soon he forgot about the others. How many days had he been gone? Did it matter? As long as Castro kept bringing him food…

Rescue Attempts

To the rest of the castaways, Lowell and Castro seemed to have vanished. A group of four men were dispatched to find the Professor and his amanuensis, but Lowell trapped them in the cave and imprisoned them in the oubliette. Erasing all evidence that they had entered the caldera, Lowell concealed the entrance and continued his work. Castro was next in the tank, but something went wrong. He emerged in a state of partial derangement, and repeated exposures only worsened his condition.

In the meantime, salvation arrived at Banks Cove in the form of the Jupiter, a British whaler commanded by Thomas Cotton. Captain Cotton agreed to mount a second rescue party, but five days of fruitless searching found no trace of the missing men. Bidding their lost comrades a sad farewell, the remaining survivors of the Atlantis departed the island.

Three weeks later, the Jupiter vanished at sea.

Madness

The Good Doctor continued his downward spiral. Deaf to the pleas of his former shipmates, he kept them confined to the oubliette and allowed Castro to supply them with food and water. The first to be killed was the second mate, Anthony Manley. Lowell’s closest companion on the Atlantis, Manley seemed an excellent candidate to share Lowell’s enlightenment. The Professor escorted him to Thal’n’lai and invited him to enter the communicant’s tank, but Manley refused. Upon returning to the cave, the second mate tried to overpower Lowell. Castro stabbed Manley in the throat with the stylus and dumped his body into the pit.

Things went rapidly downhill. As food became scarce, the prisoners stopped receiving meals. They were forced to consume the body of their former officer. Now that the taboo of cannibalism had been broken, Lowell plunged headlong through the gates of atrocity. A few weeks later he butchered and cooked midship oarsman Douglas Fisher. The following month, Charles Thomas was subjected to living vivisection in the name of “science.” His dismembered body parts were tossed to the starving prisoners like offal.

Meanwhile, Lowell continued his sessions with the Elder Thing. Eventually he reached the limits of what could be learned through second-stage Contact. In order to continue, Lowell had to undergo Communion with the creature on a physical level; and to do that, the Elder Thing had to alter Lowell’s nervous system. Lowell would have to enter the creature’s tank and allow it to sculpt new orifices into his body, interfaces for the Thing’s ganglionic tendrils. Before Lowell consented to this procedure, he needed to understand exactly what it entailed—he had to research the procedure himself. One prisoner remained in the oubliette, but Karl Brophy was too weak to survive the ordeal. That left only Lowell’s faithful companion, the one soul he’d yet to betray.

It took several weeks of exploratory surgery, but the data was invaluable. The Elder Thing was right—direct neural contact was needed. The flesh could be modified. And unlike Lowell’s operations on Castro, the Thing’s modifications would be painless. Actually, even…pleasurable.

Lowell flung his mutilated assistant into the oubliette and celebrated his success with a bowl of turtle-and-Brophy soup.

The Delusion

At this point, Lowell was completely insane. Perhaps to preserve a flicker of his remaining humanity, his delirious brain fabricated a beautiful delusion: the K’th-thyalei prison was Lowell’s home in Cambridge, the Elder Thing was his wife Sarah, and the surgical operations were erotic encounters. In Lowell’s mind, he was crawling into a warm bath with his eager lover. In reality, he was lowering himself into a tank where an alien biologically engineered orifices into his flesh. Seven orifices were required for Communion, each session in the tank bringing Lowell one degree closer to perfection. On the eight session, the Elder Thing would transfer its consciousness to Lowell’s brain. He would become one with Sarah.

Nine months after being shipwrecked, Lowell was finally ready. Slipping into Sarah’s claw-footed tub, his new orifices opened to receive her love.

But something went wrong. As the Elder Thing downloaded its consciousness into Lowell’s demented brain, the Professor’s mind—or soul—finally shattered. Sarah’s mind was flung back into her decaying body. Lowell scrambled from the tank, howling and alone.

It took Lowell three days to return to the cave. Castro had managed to escape the oubliette and was nowhere to be found. Working in a daze, Lowell cleared the pit of human remains and hid them behind the Zodiac Door. A few days later, he spied a sail in the distance—it was the Rachel from Nantucket.

The Lacuna

The crew of the Rachel found Lowell wandering Banks Cove, croaking for help in a strange, guttural language. Filthy and bearded, the crazed hermit could not recall his name, or how he had arrived on the island. Promising to “show them something philosophical,” he escorted them to the cave, but his garbled attempts to explain his “testimony” fell on deaf ears. Nor could Lowell recall how to open the Zodiac Door. When Lowell lashed out at one of his rescuers, the harpooneer William Hart laid him flat on his back. Taking the deranged amnesiac under their care, the Rachels delivered Lowell to a convent in Salinas.

When Lowell finally came to his senses, he found himself in a hospital bed attended by Spanish nuns. The last nine months of his life were missing, excised from his memory with surgical precision. All he remembered was the shipwreck, and the survivors making their way to Banks Cove. Everything after that was a total blank.

Lowell began calling this period “the Lacuna.”

Believing his ordeal was over, Montgomery Lowell attempted to resume his old life. But Lowell was unaware that his mind was still actively colluding with madness and delusion! The Lacuna may have erased his experiences on Albemarle, but it also erased the very existence of Rafael Castro, and continued to smooth over the rough edges of his increasingly-troubled life. After Lowell’s mounting eccentricities cost him his position at Cambridge, his wife left him, and he took a razor to his wrists. Lowell’s housekeeper Felicity found him bleeding in the bathtub, attempting to thrust one of Sarah’s stockings into his wound and muttering something about ganglionic tendrils. His colleagues covered up the suicide attempt, but Lowell was quietly placed on academic leave. Still operating in failsafe mode, Lowell’s brain deleted these traumatic events as well. In fact, Lowell has completely repressed the fact that he even had a wife, mentally rewriting his history to omit Sarah’s presence completely. And the scars on his wrists? He can look at them all he wants, but all he sees are injuries received during the shipwreck of the Atlantis.

D) Approaching Albemarle: Lowell’s Nightmares

As the Galápagos Islands are approached, Professor Lowell begins experiencing an irresistible pull towards Albemarle. His days are troubled by migraines and brown studies, and his nights are unsettled by terrible dreams. He begins recalling tantalizing insights about evolution, quantum physics, astronomy and biology—as well as suffocating nightmares, many of which suggest that revelations are just around the corner. The Keeper should use this opportunity to reveal more of Lowell’s repressed experiences, slowly dissolving the Lacuna and reawakening memories of his estranged wife Sarah, his time on Albemarle, and his attempted suicide in London. Images of cannibalism, horrible experimentation on living humans, erotic dreams with highly disturbing components—all revolving around “Sarah,” who enters his dreams with increasing lucidity, beckoning him towards one final, fleshy reunion, the consummation of their love.

E) Approaching Albemarle: Morgan’s Dreams

Dr. Lowell isn’t the only one who senses something awaiting him on Albemarle Island! By the time the Quiddity reaches the Galápagos, Leland Morgan will be approaching Stage 3 of his Transformation into a Deep One. The Keeper should make life fairly uncomfortable for Morgan, visiting him with dreams, nightmares, and wild thoughts of sex and cannibalism. Among these sensations should be the certainty that something waits under the sea, just for him—some legacy, some heritage. And paradoxically, the only way to go down is to go up—up the slopes of Lowell’s accursed volcano…

F) Expedition to Volcán Wolf

There are two narrative pathways to Volcán Wolf. Interested player characters may be open about their desires and enlist Pynchon’s assistance, or they may use subterfuge and strike out on their own.

Option 1: Planning an Expedition

How honest the Professor and Morgan have been with Joab and Pynchon is entirely up to the players; but if they want permission to explore Volcán Wolf, they’re going to have to open up to some degree. Fortunately Pynchon is a die-hard cultist, and anything with Mythos overtones is going to capture his interest, from “cave covered with revelations” to “ancient power submerged below the waves.” Of course, Morgan may have to disclose more than Lowell—Lowell’s history at Volcán Wolf is well-known, but Morgan’s ostensibly a simple (i.e., human) blacksmith. (Though he may certainly ride Lowell’s coat-tails—“The crazy professor wants to explore the mountain? That’s cool, can I come along?”) Joab is less intrigued by possible Mythos connections than Pynchon, but he’ll allow his first mate a week to explore the island while he prepares the Quiddity for an extended period of whaling.

Pynchon’s Visions

One way the Keeper can push characters towards the “open” option is by having William Pynchon sense the proximity of the Gate to Thal’n’lai. Of course, he won’t understand exactly what he’s sensing; but the wily cultist knows there’s something important about Volcán Wolf. Something so important he’s willing to mount an expedition, and who better to accompany that expedition than Albemarle’s famous castaway?

Option 2: Desertion

If player characters don’t want to involve the officers, they may quietly desert the ship at Banks Cove. It’s certainly the more foolish of the two options, and players should fully understand the consequences of going AWOL. Desertion is met with an armed response, with Pynchon (or Coffin) leading a squadron to track down and retrieve the runaways. Even if the trip to Volcán Wolf proves justified, Joab insists the deserters receive some form of punishment—Lowell may be ejected from the captain’s cabin, while Morgan may be denied future shore leave.

The Republic of Caliban

The main antagonists of Chapter 4 are the Republic of Caliban, a group of castaways centered around a Jesuit geologist named Ingo Quiring. Inhabiting Lowell’s cave since 1840, lately the Republic has been conducting raids on unsuspecting sailors. Magnetized by the Call of Dagon, the Republic has fallen under the spell of the Elder Thing, and have pledged to release the creature from its prison and transport it to the Black Island. (See Ingo Quiring’s NPC profile and the Republic of Caliban NPC profiles for statistics and details.)

Brief History of the Republic of Caliban

On 15 April 1840, Lowell’s cave was discovered by an epileptic Jesuit named Ingo Quiring. Father Quiring translated the bulk of Lowell’s “testimony” and learned how to open the Gate to Thal’n’lai. Like Lowell before him, Quiring entered the communicant’s tank and made first-stage Contact with the imprisoned Elder Thing. Having been successfully Baptized, Quiring began the longer process of Confirmation. As his Sanity deteriorated, Quiring began to view the Elder Thing as an imprisoned faerie or daemon, Shakespeare’s “Ariel” confined to the tank’s “Cloven Pine.” That this formulation made him “Prospero” was a comparison he rather liked…

Ariel Hears the Call

When Ingo Quiring lowered himself into the communicant’s tank he was already suffering from Stage 1 Call of Dagon. The Elder Thing had never experienced the Call—the Deep Ones did not hear it, and Lowell and Castro arrived during a period of quiescence. But here it was, the Call of Dagon resonating from Quiring’s brain like the peal of bell, a psychic imperative to open the Abyss and trigger the Apocalypse; emanating from nonother than K’th-oan-esh-el, the very god dethroned and dismembered by the Elder Thing’s original captors! And if the Abyss could be opened, the Terrestrial Equation could be reset. Reality could be re-written. Humanity could be extinguished, the Dreamlands destroyed, and the Elder Things set free. (See “Background Part 4—Pocket Dreamworlds.”)

From that point on, the Elder Thing cultivated a new obsession in Quiring’s brain. The Jesuit—and all who followed him—must free the Thing from its prison by the time the Abyss opened in June 1846. The best method was Possession, but Quiring was neither as intelligent nor resilient as Lowell. If it couldn’t transfer its consciousness into a human being, the only remaining solution was to be physically transported to Kithaat, the Black Island. That would require a crew and a ship to carry them—no mean feat. But wasn’t the Call of Dagon already driving sailors to the Pacific? It was a desperate plan, but after 50 million years of isolation, what other hope was there? Unless of course Lowell came back to Sarah. But that was unlikely, so best for Quiring to develop a following.

The First Caliban

A few months after Quiring discovered Ariel, he received his first visitor to the cave—Rafael Castro, Lowell’s discarded sketch artist and medical lab rat. More amused than horrified by the Spaniard’s appearance, Quiring took Castro as a servant, promising to cure his condition through the “magic” of Ariel. Needless to say, Quiring dubbed the broken creature “Caliban.” When it was time to expose Caliban to Ariel, Castro balked—he’d already been down this road, and had no intentions of meeting “the master’s wife” again! Quiring attempted to force Castro into the tank, and el monstruo emerged. The Jesuit was knocked unconscious and Castro made his escape, never to return to the cave.

The Thistle Mutiny

Quiring gained his first true disciples when three mutineers from the whaler Thistle arrived at Banks Cove in early 1841. The trio was led by the former mate Milo Bean, and included a cunning harpooneer named Oliver Black and a hapless greenhorn named Howard Shell. Already suffering from the Call of Dagon, Black had convinced his partners that “salvation” awaited atop Volcán Wolf. What they found instead was Father Quiring, who introduced himself as Prospero. Immediately recognizing each other as brothers-in-madness, Quiring and Black got along famously, but Bean and Shell were unconvinced by the necessity of Baptism. A few doses of Sycorax overcame their resistance. Bean emerged from the Cloven Pine a true believer, but Shell was reduced to an automaton and became the fledging republic’s first slave.

The Republic

A few weeks after the arrival of the Thistles, Dr. Nigel Vox followed the Call of Dagon up the sides of Volcán Wolf and was successfully Baptized. It was Vox who suggested they call themselves the Republic of Caliban—after all, weren’t they the true sons of the island, each warped and twisted in his own way? And wouldn’t Prospero free Ariel, then carry them all to…to the Epilogue? Whatever that was? Over the following years, castaways, captives, and communicants were enrolled in the Republic one by one: Silvio Marroquín, Carlos Moreno and Inez Apaza, Silas Grant, James Peach, Jon Keokolo, Steamboat Pete, and finally Mary Roberts. Some went completely mad at the Cloven Pine, while others refined their delusions; but one by one the Republic grew stronger.

The Theresa Incident

On 1 May 1845, a New Bedford whaler named the Theresa dropped anchor at Banks Cove. Commanded by the wealthy but eccentric Mount Sinai Butterfield, the Theresa intended to spend a day or two gathering supplies before returning to the hunt. Captain Butterfield took his harpooneer Piri Pat on a hunting expedition to the slopes of modern-day Volcán Darwin. They were ambushed by the Republic of Caliban, who were primarily interested in stealing the captain’s rifle. Piri Pat was incapacitated by a trio of poison darts, but Butterfield managed to shoot Oliver Black in the chest before he was overwhelmed and beaten with clubs. The Māori was dragged back to the cave and thrown in the slave pit.

In the meantime, a search crew from the Theresa found and buried their slain captain. The first mate blamed Piri Pat for the murder, but the party could find no trace of the missing harpooneer. Although many of the crew doubted the mate’s accusation, only Piri Pat’s fellow harpooneer Noobaloo openly defended his friend. He deserted the Theresa the evening before she sailed. A few days later Noobaloo was brought down by Sycorax while exploring the caldera. He awoke next to Piri Pat, and the pair spent the night bewailing their bondage and hurling imprecations at their captors. Eager to try his arcane powers, Father Quiring cast Bind Soul and Compel Flesh on Noobaloo, transforming the harpooneer into the walking dead. Piri Pat was robbed of his soul a few weeks later.

The Republic of Caliban: Beliefs and Goals

The ultimate goal of the Republic of Caliban is to free the Elder Thing from its prison and bring it to the Abyss. In this respect, everyone in the Republic is suffering from the Call of Dagon, but it’s been channeled, modified, and reinforced by the Elder Thing to serve its own purposes. Over the years this goal has developed its own pathology, a delusional system partially derived from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. To put it broadly, the Republic of Caliban follows Prospero, who receives his powers from Ariel. They’ve been tasked with freeing Ariel from the Cloven Pine, an act which will carry them to the Epilogue on the Black Island. Equivalent to Moneypenny’s Golden Altar or Dandridge’s Libertatia, the Epilogue is essentially Abaddon. All the Calibans understand this general idea, but what exactly the Epilogue entails is vague at best. Certainly all shall be revealed when the time comes!

Unfortunately, time is a luxury the Elder Thing cannot afford. Only four Calibans have proved strong enough to pass from Baptism to Confirmation: Quiring, Black, Vox, and Mary. Quiring has become convinced he can only begin the third stage, Communion, once the “Republic is complete,” a nebulous idea the Thing cannot dislodge from his tortured mind. Black was probably the best candidate, but the fool got himself killed trying to steal a gun. Vox is growing increasingly more unstable, and may not survive the next few sessions. Only Mary offers any real hope, so the Thing has reinforced her delusion that her unborn daughter will carry its “soul.” In reality, the Thing hopes to possess Mary and her infant’s blank brain, then manipulate Quiring into stealing a ship and sailing for Kithaat.

Plan B

The death of Oliver Black was a potent reminder that the Elder Thing has little power outside its tank. If it’s unable to possess Quiring, Vox, or Mary, the Elder Thing must resort to a desperate backup plan—the humans must carry it directly to Kithaat on a stolen ship. This is every bit as dangerous as it sounds, because the Thing has degenerated to the point where it needs the K’th-thyalei fluids to survive. The Calibans must physically haul the Elder Thing from the tank and place it in a cask filled with nutrient fluids. (The Thing can survive a few hours outside the tank, but that’s all.) Without the tank’s filtration and rejuvenation systems, the Thing will certainly perish within eight to twelve months; but maybe that’s all the time it needs.

The Arrival of Lowell

With less than a year to reach Kithaat, the despairing Elder Thing has found its prayers answered by the return of its greatest disciple. If only Lowell can be tempted back into the tank, third-stage Contact could be completed in a single session! The Elder Thing could possess Lowell, and finally do away with the irksome and unstable Republic. And if that means Ariel must become Sarah again, so be it.

Sources & Notes

The author is greatly indebted to three principle sources for this chapter. The first is Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea, which details the visit of the whaleship Essex to the Galápagos. The second is Herman Melville’s The Encantadas, Or Enchanted Isles, a set of ten “sketches” published in 1854. Drawing from Melville’s own experiences as a whaler in the 1840s, The Encantadas offers a stylized—and thoroughly embellished!—depiction of the Galápagos Islands. Melville’s sketches borrow generously from previous accounts recorded by William Cowley, James Colnett, Charles Darwin, and David Porter. The final source is John Coulter’s Adventures in the Pacific, published in 1845. A surgeon onboard a British whaler, Coulter spent quite some time at the Galápagos Islands in the 1830s. As with most nineteenth-century travelogues, Adventures reflects an uncritically colonial world-view; and his discovery of “coal” on the Galápagos Islands remains questionable, to say the least. Nevertheless, Coulter’s description of Charles Island offers a first-hand account of Villamil’s penal colony that reveals Melville’s fictionalized version as the wild sea-tale it is. And finally, the 2003 film Master and Commander must be mentioned, as its extended sequence on the Galápagos Islands is required viewing before playing this chapter!

White Leviathan, Chapter 4—Galápagos Islands

[Back to Chapter 3, Encounter 14, Gam with the Julia | White Leviathan TOC | Forward to Chapter 4: Encounters]

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 10 August 2023

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

White Leviathan PDF: [TBD]