Kaúxuma Núpika

- At March 22, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Vampire

0

0

…but what is this we here, casting their eyes with a stern look on her, is it true that the white men have brought with them the Small Pox to destroy us; and two men of enormous size, who are on their way to us, overturning the Ground, and burying all the Villages and Lodges underneath it; is this true, and are we all soon to die. I told them not be alarmed, for the white Men who had arrived had not brought the Small Pox, and the Natives were strong to live, and every evening were dancing and singing; and pointing to the skies, said, you ought to know that the Great Spirit is the only Master of the ground, and such as it was in the days of your grandfathers it is now, and will continue the same for your grandsons. At all which they appeared much pleased, and thanked me for the good words I had told them; but I saw plainly that if the man woman had not been sitting behind us they would have plunged a dagger in her.

—David Thompson, Journals 1807-1811

Kaúxuma Núpika

Clan: Gangrel antitribu

Affiliation: Byzantium Coven

Role: Oracle

Introduction

Every important Sabbat coven has an oracle, a Cainite tasked with using clairvoyance and precognition to protect and advance the pack. Generally drawn from the ranks of Tzimisce and Tremere antitribu, oracles are granted their title by La Reina Bruja, and unlike other Cainites, may not depart their coven unless granted permission. For most of its history, the Byzantium Coven was not assigned a formal oracle—Venus and Orchid seemed to fulfil the role quite well herself! But as the “Cult of Venus” gained momentum towards the end of the century, the Latrocinium Council decided the coven required a traditional oracle, one who was unconnected to Venus from her time in London or New York. They selected Kaúxuma Núpika—more commonly known as Xuma—a transgendered Gangrel from Montréal, an elder who began life as a Kootenai prophet and seer. Drawing her oracular power from sexually-charged journeys into a private “Dark Land” of clairvoyant symbols, Xuma seemed like the perfect choice. Trained by the Sabbat in Montréal, the source of her talents was alien to Venus’ classical magicks, she was fiercely loyal to the Sabbat, and she had a voracious sexual appetite. What could go wrong?

Description

Kaúxuma Núpika began life as a Kootenai Indian, a member of a peaceful band of hunters from the Creston region of British Columbia. Standing slightly over six feet tall with a sturdy, muscular frame, Xuma considers herself to possess the body of a woman and the spirit of a male. Preferring the pronoun “she,” Xuma dresses in plain clothing with a distinctive Western flair, favoring jeans, embroidered shirts, leather boots, and frequently sporting a Stetson cowboy hat. She wears her hair long and free, and over the years her Gangrel blood has given her Kootenai features a sleek, leonine appearance. She rarely wears any jewelry, but often paints her face with simple symbols denoting her relationship with the spirits of the Dark Land. Xuma speaks in a masculine, low-pitched voice with a slight Québécois accent, and is fluent in sixteen languages, from her native Ktunaxa to a smattering of ancient Greek.

Personality

Xuma has a taciturn personality, rarely wasting words and keeping to her immediate circle of acquaintances. Although the years have granted her a certain degree of restraint, she still possesses the quick temper and stubborn character of her youth, and has learned to avoid situations that “bring out the beast,” as she refers to her Gangrel nature. She is sexually voracious, seeking new lovers whenever the mood strikes; but few of these young women are invited back for a second visit. Xuma is only romantically attracted to a single woman at a time, forming intense partnerships that last for many years. Unfortunately, most of these “marriages” have imploded in fits of jealousy and rage. The exception is her current wife Mixie. The only ghoul Xuma ever created, Mixie has remained by her side for over a century.

Feeding Habits

Xuma is a cautious feeder, and only drinks from humans during sex or Sabbat rituals. She prefers to maintain a limited group of feeding partners, and generally takes only what she needs. Despite her tempestuous history of violence, she rarely slips into a frenzy—Xuma prefers to release her aggressions on animals when in panther form. This reluctance to commit murder is balanced by a particular passion for diablerie, and there is nothing Xuma craves more than the vitae of a fellow vampire. This makes her a devoted member of the Vinculum, a fierce sexual partner, and a very dangerous foe. In combat, Xuma unshackles her humanity and becomes a wild animal, enjoying the hot spray of Kindred blood and rending her enemies limb from limb. She calls this fury her “Scalp Dance,” and those who’ve witnessed Xuma in battle are often shocked to discover she’s an oracle, not a warrior. To Xuma, there’s little difference. Once you’ve grasped the un-language of the Dark Land, the names of the waking world are merely limitations to be cast aside. Oracle, warrior; man, woman; white, red; civilized, savage; human, beast—doesn’t the Sabbat teach that dichotomies are merely “asses” to “be set to grind corn?”

History

Over the course of her long and fascinating life, Xuma has borne many names and witnessed many strange events; but her story begins in 1790 with a volcanic eruption. The volcano was Mount St. Helens, and though it was five hundred miles away, it marked Xuma with an apocalyptic birthname and granted her the gift of second sight.

Rain of Ashes

The morning Xuma was born, an ominous sky began raining ash. An inexorable downfall of trembling grey petals, the ash covered the trees, drifted over the valleys, and poisoned the crystal rivers. Over the course of the day, the sun was extinguished and the clouds obliterated. By the time the last flakes settled into place the following afternoon, the earth in every direction was blanketed under ten inches of ash. The sky was the color of mushrooms; it was impossible to see from one lodge to the other; the sounds of coughing muffled by the hazy gloom. Near nightfall, the ashen rain began again.

Perceiving the ash as a sign of the sun’s displeasure, some Kootenai worried that the spirits of the dead could no longer find the setting sun. They made offerings of song and dance to please the three supreme akínakat, praying for the sun’s return and a restoration of order. A few of the more superstitious Kootenai believed the situation was even more dire. Seeing the rain of ashes as a sign of the apocalypse, they began preparing for the dead to return from the mysterious east. The akínakat would allow the dead to embrace their living relatives; but the wicked would be transformed into rocks, serpents, and frogs. The gods would crash the moon into the earth—unless of course, they have already done so; in which case everyone had been judged wicked. These terrified souls began painting funeral stripes of red, blue, and green upon their faces, dancing in the ashes until they toppled from exhaustion.

Many members of Xuma’s band scoffed at these fanatics and worriers, claiming the rain of ash was a natural phenomenon. Didn’t that old flathead woman once tell a story about a fiery mountain that covered her tribe with ashes, only to be washed away in the rain the following day? Xuma’s mother and father belonged to this group, and sensibly remained in their lodge, their attention diverted by the birth of their new girl.

Whether it was the conclusion of a natural phenomenon or the result of answered prayers, the rain of ashes stopped the following day. The sun emerged from a hazy sky, exposing countless deer tracks in the swirling grey drifts. Hunting parties were dispatched, and returned victorious—the animals of the forest were stunned by the fallout, some willingly accepting their deaths rather than struggle further through the unforgiving terrain. During the feast that followed, the baby girl was given the name “Rain of Ashes” and properly celebrated, her tribe remarking on her robust size and the strength of her cry. Surely a baby born on that fateful day would have special gifts? The oldest Crazy Owl was escorted to the baby’s lodge to offer her learned opinion. Taking one look into Xuma’s alert eyes, the healer chuckled—“This one’s going to be trouble.”

The old woman was not wrong. As Rain of Ashes matured, she acquired a quick temper and stubborn character to accompany her increasingly masculine physique. When she was six years old, the Crazy Dogs came to her family’s tipi to take its cover for the Sun Dance lodge. Although it was considered an honor, the young girl refused to let them “steal” her father’s precious bison skin. She clung to the hide the entire way to the lodge, her parents horrified as the warriors and accompanying singers laughed at her antics. After her mother punished her vigorously, Rain of Ashes spent the rest of the summer pretending to speak to the “spirits” of the forest, spirits who “instructed” her to take up a toy bow rather than learn the arts of basketmaking and preserving camas. Some in her tribe began calling her a títqattek, or “girl pretending to be a man.”

This rebellion lasted nearly a year, until her father became ill while fishing for salmon. After that, Rain of Ashes acquiesced to her mother’s wishes, watching enviously as her brother Broken Flint stepped forward to fill his father’s shoes. Her father died two months later, speaking his last words into her ear—“Be a good daughter.”

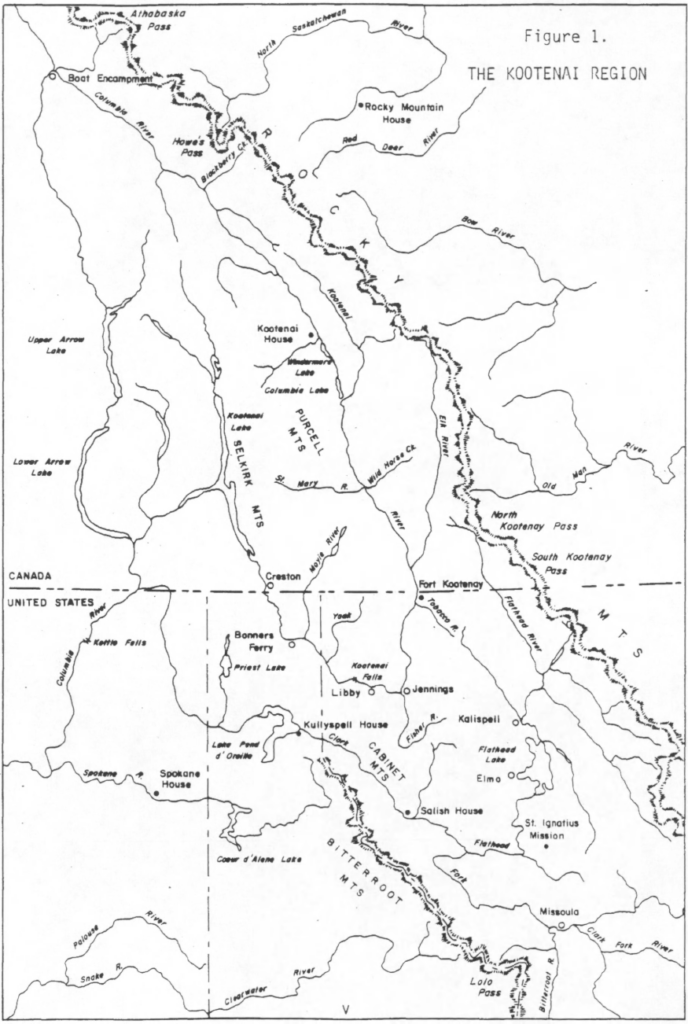

From Cynthia Manning’s “Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians”

From Cynthia Manning’s “Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians”

Qúqunok Pátke

On her eleventh birthday, Rain of Ashes was renamed Qúqunok Pátke, or “Standing Lodgepole Woman.” Ostensibly a commentary on her size and strength, it was not lost on the girl that lodgepoles were also known for their inflexibility. As if her boyish body and brazen personality weren’t enough to keep her adolescence troubled, with puberty came a new set of problems. As soon as she started menstruating, her previous “pretend” powers became significantly less imaginary, and young Qúqunok Pátke began manifesting the powers of a shaman. A traditionally male role in Kootenai society, medicine men were permitted special privileges; women who experienced visionary dreams were encouraged to become healers. Xuma adamantly rejected this direction, insisting that her dreams were very different than the “female” visions of the Crazy Owls. Xuma was a traveler to the Dark Land.

The Dark Land

Ever since her first moon time, Xuma’s nights were disturbed by journeys to a “Dark Land” on the hypnagogic borders of sleep. More like a presence masking itself as a place, this Dark Land was both alien and familiar, a trackless world of impressions and sensations that unfolded around her dreams. On nights when the Dark Land was particularly lucid, some of Xuma’s dreams carried the weight of premonition. When she was twelve, Xuma predicted the worst blizzard in tribal history, and she foresaw that Little Foot would drown just before the Grizzly Bear Dance. She correctly claimed that a white moose would pass through her village shortly after the moon turned red, and in 1807 she prophesied the imminent arrival of white explorers. Although her mother told her to keep her dreams to herself, frankly Xuma enjoyed the attention. She began to interpret other people’s dreams; and if those “interpretations” were sometimes embellished according to her own likes and dislikes, well—shouldn’t nice things happen to good people, and bad things happen to bad people? Or at least, people who were not nice to awkward girls who were trying to tell adults the truth?

An unhappy childhood matured into a lonely adolescence, and soon Standing Lodgepole Woman was experiencing physical and spiritual longings she couldn’t satisfy with mere dreams. Finding it difficult to attract a husband, she began spending time with the white voyageurs. She was fascinated by their bearish frames, their rough beards, and their soft, toneless languages. After a particularly nasty argument with her mother in 1808, Qúqunok Pátke left her village in the company of David Thompson, known to the natives as Stargazer. She traveled with his group under the flag of the North West Company, serving as local guide and interpreter. She quickly became the “country wife” of Augustin Boisverd, one of Thompson’s French-Canadian voyageurs. While Qúqunok Pátke was somewhat skeptical about the legalities of their brief “marriage ceremony,” Augustin enjoyed her forthright character, was willing to learn some Ktunaxa, and genuinely appreciated her “big-boned” body.

The first time Xuma had sex was a revelation. Not because of the sex itself—that was exactly as she had expected, full of grunting, bizarre odors, and a general lack of fulfilment on her part. But the sheer carnality of the act triggered a welcome rush of energy, and after she brought herself to orgasm once Augustin fell asleep snoring, her dreams were extraordinarily vivid. After a few more nights of one-sided sex, Xuma demanded that her husband focus more attention on her own needs. At first, Augustin seemed surprised; but she showed him how to use his hand correctly, and soon he became quite eager, especially when she began to moan and squeal with genuine delight.

Of course, Augustin never suspected that the “promiscuity” of his Indian wife was intended to satisfy her spiritual needs as much as her physical cravings. But each time Xuma experienced an orgasm, her dreams came into sharper focus, and the Dark Land became more intelligible, an un-language composed from impressions, glimpses, and contours. Sometimes she could even sense possibilities, radiating outwards like the branches of a tree. While not every vision came true, she refined her ability to sift through these branches and select one that seemed the most sturdy, the most reliable. As Xuma shared her dreams with the voyageurs, they began referring to her as la petite sorcière. Apparently in the white world, women were traditionally the ones with such gifts; and while some of the voyageurs viewed her with suspicion, it was because of her powers, not in spite of them.

A few months after their marriage, Augustin and Xuma were hunting with a British trapper named Robert Pettigrew. The trio were caught outside in a sudden blizzard, the result of miscommunication and poor planning. Taking shelter from the storm in a makeshift hangard, Xuma nestled between the two men for warmth. After a few tentative touches and a grunt of assent from Augustin, they were both treating her like a wife. And Augustin, though certainly no kupalketek, seemed surprisingly eager to please Robert. After that night, she was free to visit Robert alone. It didn’t take long for the Englishman to share her with another woman, a shy Cree the men called Honey. And that—well, that was simply wonderful. Robert let Xuma take the lead, and she took to the more assertive role with great relish. Honey was soft and delicious; her mouth, her breasts, her hips—everything was soft and delicious. The four began having regular sex in various configurations; but it was always Honey that made Xuma the happiest.

Needless to say, Xuma developed the kind of reputation one might expect surrounding a sexually active Indian woman, and her “loose” manner as a “courtesan” began generating friction among Thompson’s native allies and his more religiously-inclined voyageurs. The situation became impossible to ignore when Xuma turned her attention to Klootchie, a Chinook half-breed whose husband recently returned to his white family in Churchill. Klootchie was unhappy with Xuma’s advances; and while her status as a half-breed gave her few options, she was not about to be seduced by a licentious berdache. She made her discomfort public, and Thompson was forced to act. In 1810, Qúqunok Pátke was dismissed from Kootenae House trading post.

Augustin Boisverd was disappointed by his “divorce,” but he had his own problems, and rumors of sodomy dogged his heels for the rest of his life. After suffering a rupture falling from his horse, he travelled deeper into Canada and continued exploring the northwest. He died of old age in Toronto in 1853. Robert Pettigrew was killed during the Battle of the Thames in 1813, Honey married a Sandwich Islander and moved to Nantucket, and Klootchie turned to prostitution and was beaten to death by a French drunkard in Williamstown. Only David Thompson himself would again encounter Qúqunok Pátke, and by then she’d have a different name.

Photograph by Barry A. Taylor

Kaúxuma Núpika

Exiled from her life among the contradictory whites, Qúqunok Pátke returned home with a mixture of reluctance and relief. In the tradition of prodigal children everywhere, she took the opportunity to reinvent herself. Appearing suddenly during the Sun Dance, she announced that her name was now Kaúxuma Núpika, or “Gone to the Spirits.” Dressed like a voyageur and carrying a battered Charleville musket, Xuma announced that something else had changed besides her name—she was now a man, her sex changed by the magic of her white husband! She performed a dance to relate the story, but despite the skepticism of her people, Xuma refused to offer actual proof.

To the amusement of her tribe and the embarrassment of her family, Kaúxuma Núpika proceeded to dress like a man, act like a man, and took up hunting, sporting, and gambling. Her people again referred to her as a títqattek, but Xuma rejected this characterization—she was a man, complete with a penis and a desire to take a wife. Frightened by her intensity, many eligible brides fled from Xuma’s aggressive overtures, and she was forced to broaden her search.

Pretty Duck

Eventually Xuma came across Pretty Duck, a young woman from the Upper Kootenai whose husband had divorced her for infidelity. At first, Pretty Duck was incredulous of Xuma’s claims; but when Xuma revealed a “penis” made from leather, the divorcée understood. Not sure whether Xuma was incredibly ambitious or just crazy, Pretty Duck decided to accept her offer, and they settled down with Xuma’s family, now consisting of her terminally depressed mother, her spiteful older sister, and her combative younger brother, Broken Flint. Over the next few months, Xuma played the role of husband, bringing home game and practicing her shamanistic powers openly. As people discovered the accuracy of Xuma’s predictions, they began accepting her story. The couple even attracted a servant, a simple orphan named Flashing Fish who considered Xuma to be a prophet. Content with her renewed social status and satisfied by Xuma’s leather strap-on, the irreverent Pretty Duck laughed at the inevitable questions and tribal gossip—“Oh yes, of course I’ve seen his cock, and it’s huge!” Privately, things were less harmonious, as Xuma treated Pretty Duck roughly, perhaps overcompensating as she adopted a more masculine role. There was also Xuma’s passion for gambling, and various objects began to mysteriously appear or disappear from the lodge in accordance to the waxing and waning of Xuma’s fortunes.

In the summer of 1810, Kaúxuma Núpika finally “proved” her manhood, taking part in a raid on the neighboring Colville tribe and returning with her first spoils of conquest. The happy warrior came home to find Pretty Duck hastily concealing evidence of an affair. Enraged, Xuma lashed out with her bow and struck Pretty Duck across the face. In response, Pretty Duck accused Xuma of being a terrible “husband,” caring more about her own pleasure and recently gambling away their prized canoe. The quarrel grew increasingly more heated, and Xuma struck her wife a second time. Pretty Duck snatched the bow from Xuma’s hands and ran outside. As Xuma stepped from the lodge, she found Pretty Duck shooting arrows into the sides of the leveraged canoe. Sprinting towards her wife in a rage, Xuma was stunned when Pretty Duck loosed an arrow at her heart. The shot went wide by a mere hand, passing through the hemp mat of their lodge and glancing off the stock of Xuma’s musket. It was the end of their short marriage; Pretty Duck returned to her people up north, and Kaúxuma Núpika took up with Flashing Fish.

Qánqon-kámek-klaúla

Despite the success of her first raid, not everyone in the tribe was willing to believe Xuma’s story about her magical sex change, and she remained a source of constant speculation. Indeed, the truth was almost revealed during her second foray into war, an attempt to steal horses from the southern Kalispel. As the prospective leader of the raid passed through the village thumping on a painted caribou hide with his war stick, Broken Flint announced his intentions to join the party, and Xuma asked to accompany her brother with her knife and musket. The party left the next morning, but found the Kalispel camp abandoned two days later. Friendly locals informed the Kootenai that their targets got wind of the raid, so they’d best take precautions when returning to their village. This meant crossing the rivers in groups—one group to cross, and one to remain armed and guarding against retaliation.

Because it was the custom of warriors to undress as they waded across rivers, Xuma was worried that she’d be exposed, both figuratively and literally. As each crossing arrived, she found an excuse to remain behind, ensuring privacy when she forded the river to catch up. Sensing an opportunity to finally learn the truth, Broken Flint hid himself to observe her crossing. Xuma spotted him just as she stripped off her shirt, her breasts coming free from their binding. Horrified, she squatted down into the water to conceal herself, pretending her foot was trapped. Snorting in derision, her brother hurried up to join the party—but kept his peace.

Although the raid was unsuccessful, they had escaped enemy territory without incident. That night the leader declared that his warriors were free to select a new name. With her eye on her sullen brother, Kaúxuma Núpika defiantly adopted the masculine name Qánqon-kámek-klaúla, or “Grizzly Squatting in the Water.” She was relieved when her brother only shot her a contemptuous glance. For now, her secret was safe.

Qánqon

A few weeks after the raid, Qánqon-kámek-klaúla was back to her old ways, and was overheard beating her new wife. This time, her companion failed to cook her food appropriately, and had the temerity to request a “smaller” phallus. The fight was loud and dramatic, and Flashing Fish made no attempt to conceal her cries. Disgusted by his sister’s crude behavior, Broken Flint finally exposed her story as a lie. As further insult, he refused to use her new name, shortening it to Qánqon—“You are no grizzly bear, sister. You must squat to pee, so I shall call you Squatting.” Xuma become the subject of tribal ridicule once again, along with her short temper, her leather dildos, and her claims to be a prophet. Flashing Fish joined their scorn, and openly denied that her “husband” had any supernatural powers, accusing Xuma of faking her visions in order to have “unnatural” sex. In response, Qánqon-kámek-klaúla beat the girl senseless and finally departed her tribe for good.

Gone to the Spirits

Returning to her former name, Kaúxuma Núpika spent the following year wandering the wilderness, presenting herself as a man and a prophet. Liberated from the corrosive disbelief of her tribe, her powers as a visionary grew stronger. The dream-language she glimpsed during her days with Augustin was becoming more clear, a strange alphabet of glowing symbols she felt more than saw, like traces of the wind across her body. The whites came to regard her as a capable guide, courier, and interpreter, while the natives considered her a seer. As she tried to relate her experiences to other people, she discovered that her newfound clarity did not translate into better communication skills, and her typically brusque manner won her few friends. Xuma relished being the center of attention; and if she was free from her family’s negativity, she was also untethered from the social pressures that encouraged modesty and restraint. She seemed oblivious to the impact of bad news, and predictions of disease, tragedy, and misfortune were delivered in a dramatic tone that seemed uncomfortably close to enthusiasm.

Klaúwampatki

It was around this time that Xuma met Klaúwampatki. Employed as a courier for the whites at Spokan House, Xuma was staying with a northern clan of Chinook, a small band of beaver trappers and fishermen who valued her abilities to negotiate their trades. One night the village was visited by another Kootenai, a young woman from a northern band who called herself Klaúwampatki, the “Returned Woman.” Free-spirited and comely, the woman dressed in Plains fashion and bore appalling scars upon her throat. Klaúwampatki had arrived at the confluence of the Spokane rivers to speak specifically with the “famous shaman” Kaúxuma Núpika. Troubled by a series of terrible dreams, Klaúwampatki related them to Xuma with a quiet passion, stories about white monsters that dwelled in the north, spreading a ghastly infection through the natives of the region. She was granted these visions by a “blood spirit” that entered her body two years ago through a “hole” in her throat. Placing Xuma’s fingers on her scars, Klaúwampatki looked solemnly into her eyes. “My people were originally from the Big Village. Before the plague took them. Every night I see the darkness coming closer.” Xuma wasn’t aware she was lovingly tracing the contours of Klaúwampatki’s neck until the other woman gently removed her hand and began kissing her fingertips.

As Klaúwampatki continued visiting her lodge, Xuma found herself falling in love—and miraculously, wondrously, the feeling was returned. Although she was young and astonishingly beautiful, Klaúwampatki had rejected all the warriors of her tribe; earning her the mocking title of Tínlam, or “Old Woman.” It wasn’t until meeting Kaúxuma Núpika that Klaúwampatki finally understood why she wasn’t interested in the warrior’s clumsy overtures, their sharp bodies, their preening bravado.

The first night they made love, Xuma felt a satisfaction, peace, and wholeness that she had never experienced with any other partner. That night, the Dark Land emerged from sleep as a living terrain, pressing its dream-language into her flesh like letters in clay. Unfortunately, the visions were anything but peaceful, and Xuma awoke in a cold sweat, her head a riot of monstrous images—a world of enormous giants, reeling across the rivers and mountains and destroying everything they touch, burying villages beneath the earth and poisoning native blood with disease. Shaking her lover awake, Xuma described her dreams, and recognition dawned in Klaúwampatki’s eyes. Still, the Returned Woman shook her head—“You cannot tell people this. They will not listen, and you will find them unhappy with the messenger.”

Stubborn as always, Xuma paid her lover no heed, and informed the Chinook of the coming calamity. At first, they were hesitant to believe her, but her feverish intensity won them over, and word began spreading.

A few weeks later Xuma was summoned to the trading post by its overseer, a red-haired Scotsman named Finan McDonald. Explaining that he had an important mission for a capable Indian guide, Xuma was given a package for John Stuart, the master of Fort Estekatadene in New Caledonia, some four hundred miles to the west. Pleased to be entrusted with such a responsibility, Xuma was oblivious to the real nature of the mission—a make-work errand designed to rid Spokan House of “its most troublesome native.” Not only had “Ko-come-ne-pe-ca” been making inappropriate comments to McDonald’s Salish wife Peggy, her recent fondness for apocalyptic tales was infecting the natives with confusion and hysteria. The last thing Spokan House needed was Indians obsessed with the Prophet Dance, the growing belief that the dead would return and purge the land of white invaders. It would take months for the troublesome berdache to reach the Frazer River—that is, if a bear didn’t gobble her first!

Klaúwampatki agreed to accompany Xuma on the dangerous journey, and after a week of preparations they began paddling down the Spokane to the Columbia. Along the way, Xuma continued to ignore her lover’s advice, broadcasting her alarming predictions as she traveled downriver. Not every band was eager to hear of their coming extinction, and the pair were forced to flee with their lives on more than one occasion. Klaúwampatki persisted in her attempts to curb Xuma’s behavior, but Kaúxuma Núpika had been “chosen” as a prophet for a reason, and only became more stubborn.

Their tensions finally came to a head while paddling towards Little Beaver Lake. Frustrated by Xuma’s mounting self-importance, Klaúwampatki finally revealed the story behind her name, “Returned Woman.”

Sulee

Klaúwampatki’s original name was “Sulee,” a name her mother believed captured the birdsong heard when she was born. Two summers ago, Sulee encountered a monster while returning from bathing. The monster had the shape of a white woman, but was half-human and half-beast, and set upon Sulee like a ferocious animal. Pinning her down, the monster began drinking her blood, leaving Sulee drained and terrified before bounding back into the forest like a panther. The next week, the monster attacked again, this time when Sulee was picking flowers in the moonlight. Two weeks later, Sulee was stolen from her lodge; but now she submitted with a queer docility, like the monster had bound her will under the yoke of a powerful magic. The following week, Sulee walked into the forest alone, shed her garments, and lay down willingly upon the moss. Or perhaps not quite willingly—things had become cloudy; and each time Sulee gazed into the monster’s beautiful, golden eyes, she felt more under its spell. Soon the monster began conversing with Sulee, its broken Ktunaxa heavily accented with French. And soon after that, Sulee found herself no longer thinking of the monster as an “it,” but as a “she.” And then, just as “Amalia.”

One night her two brothers secretly followed Sulee into the woods. Aghast at what they witnessed, they attacked the monster with arrows. Becoming enraged, Amalia transformed into a panther and attacked the brothers, tearing them to pieces and gulping their hearts like bursting fruit. Frenzied with hot blood, Amalia turned upon her mortal lover and sank her teeth into Sulee’s throat. The bite would have been fatal, but Amalia immediately came to her senses. Transforming back into human form, she threw herself upon the dying Kootenai and tore open her own wrists with her nails. As her magical blood poured into Sulee’s gasping mouth, a terrible energy poured through Sulee’s body. Holding her rigid, Amalia licked her throat clean, using her perfect teeth to seal the gaping wounds. She then explained that Sulee must now accept this “blood medicine” every week, or her body would begin to die. Her golden eyes glowing in the dusk, Amalia instructed Sulee to blame the attack on a wild lion, and to never speak the truth.

Confused, terrified, and stricken with grief, Sulee discovered that she could not go against her lover’s will. The next week she was back in the moonlight, and the next, and the following. With each visit, Sulee became stronger; able to run faster and move more stealthily. Her body began healing itself of any injury, and her eyes were no longer blinded by darkness. Believing that Sulee had miraculously survived the lion’s attack and had returned from the dead with magic powers, her tribe renamed her “Klaúwampatki.”

Hearing tales about a Kootenai seer, Klaúwampatki traveled to the Chinook camp to tell her story. But upon her arrival, she found that her tongue was still silenced by the monster’s will, and she could not speak truthfully about her experience. At least, not until now, not until the blood medicine had weakened, and she was far away from Amalia. And here she was, pouring out her heart to her beloved, whose own heart was so full of herself that her ears might be stuffed shut. Could Kaúxuma Núpika make any sense of her lover’s strange tale?

Kaúxuma Núpika could not. In fact, for the first time in her life, she found herself sympathetic to her family’s disbelief about her own outrageous stories. Some of which were—as she had to admit—not entirely true. The morning air filled with birdsong, Xuma accused Klaúwampatki of lying. They began arguing, the canoe drifting with the current as they unpacked several weeks of growing resentments. Finally Klaúwampatki spat, “All this time, I’ve been the one with the real power, while you pretend to be what you are not!” Her temper flaring, Xuma snatched an arrow and slammed it down on Klaúwampatki’s hand, sneering, “Heal this!”

A stunned silence fell across the canoe. Without breaking eye contact, Klaúwampatki pulled the arrow from of her hand and flung it into the river. She licked her wound, and the ragged hole closed like a mouth, leaving only an accusatory stain of blood. The pair paddled onwards in silence, returning to shore and taking separate beds.

The following week was painfully tense, neither partner speaking beyond the terse essentials. When they found shelter with a band of Chinook, Klaúwampatki was surprised when Xuma refrained from her tales of doom and gloom. Indeed, she seemed visibly chastened, taking pains to foretell only positive things. The following night, Xuma presented Klaúwampatki with a pair of new moccasins, decorated with colorful beads and porcupine quillwork. What she traded for the moccasins was a mystery, but the gift was accepted, and the breach was healed. They slept together than night as partners, Xuma crying her apologies and kissing every scar on her lover’s body—her throat, her hand, her heart.

Manlike Woman

Kaúxuma Núpika and Klaúwampatki arrived at Fort Astoria on June 15, 1811. After an interview with the whites, they realized they had made an error in navigation, and had arrived south of their intended destination by a hundred some miles. Nevertheless, their knowledge of the interior was invaluable to the traders of the newly-founded Pacific Fur Company, who were eager for more information about the beaver trade along the Spokane River. Deciding that the North West Company shouldn’t have the region all to themselves, the Astorians organized an expedition of their own, and the Kootenai were hired to guide the explorers back up the Columbia. In his attempt to rid the post of “Ko-come-ne-pe-ka,” McDonald had delivered them into the hands of his rivals.

Later that week, David Thompson arrived to take charge of the expedition. Stargazer immediately recognized “Madame Boisverd,” and informed the whites that the Indian “man and wife” were actually a pair of women, one dressed like a man for “protection.” Amused, the whites shrugged their shoulders—man, woman, or berdache, Xuma’s knowledge of the interior was worth money. The whites began calling Xuma “Manlike Woman” and “Bowdash,” the former a mistranslation of her Kootenai name, and the latter a corruption of berdache, the French term for “sexually deviant” Indians. Exposed once again by a man she trusted, Kaúxuma Núpika came to a momentous decision. It was time to embrace the dual nature of her spirit. Xuma was what she was—neither woman nor man, she was simply “Gone with the Spirits.”

The return trip was largely uneventful; however, Xuma found herself chafing at her demotion to “guide.” Hadn’t she and Klaúwampatki made it to the mouth of the Columbia River on their own? And here was Stargazer, once more in command of “discovering” her native lands and treating her like an amusing curiosity. And her fellow Indians, how they glared at her when they recognized her. Things never change—people only listen to what they want to hear, white or red, male or female, young or old. Soon Xuma began giving them what they wanted, predicting only good things no matter what her visions were showing. All she had to do was wave around McDonald’s packet and claim they were letters from the Great White Chief granting her authority to speak on behalf of the whites, promising Indians a time of peace and prosperity. While Klaúwampatki took a predictably dim view of Xuma’s cynicism, she certainly didn’t complain about the results. All along the river Chinook and Salish lined up to present the prophet with gifts—shirts of fine beaver, decorated quivers, even horses. By the time the party reached Spokan House, Xuma and Klaúwampatki had become wealthy, departing Stargazer with twenty-six horses in tow!

Settling down with Klaúwampatki near Spokan House, Xuma continued to work as a guide, interpreter, and negotiator, earning admiration and respect from whites and Indians alike. Whether they called her Kaúxuma Núpika or Bowdash, Qánqon or Manlike Woman, they came to her with problems and she solved them. She paid the cost for this prosperity during her evenings, when the Dark Land receded into the background and her visions became more dim and elusive. Klaúwampatki also paid a price. No longer in contact with Amalia, she gradually descended into humanity, her powers fading as her body returned to the cycles of natural aging.

Then one day Blackfoot Indians shot the pair full of arrows, leaving them to die as they crawled into each other’s arms.

Interlude: The Monster

The wife of a French officer killed during the Bataille des Plaines d’Abraham, Amalia Desmarais was an adventuress who actually enjoyed life in the wilderness of Nouvelle-France. Arrogant and reckless, the young woman welcomed La Conquête, as the British victory liberated her from her social station and turned her loose to roam Canada as she pleased. Eventually she fell in with a group of exiles and rogues. Moving from place to place, they raided, robbed, and debouched like a gang of highwaymen; which, perhaps they were.

One night in 1764 Amalia partook in a barbaric game hosted by French partisans outside of Québec. Astride powerful horses and dressed in English hunting gear, Amalia’s gang embarked on a human foxhunt. Drawn from a group of British captives, each “fox” was allowed a fifteen-minute start before being hounded down and shot by the drunken Frenchmen. After killing a fox, the gang would cut off his “brush, pads, and mask”—in this case, his penis, hands, and scalp—then use his blood to mark the next fox. Amalia herself led the third hunt, firing her shotgun directly into her prey, a Huguenot slavemaster named Rufus Metz. Leaping from her horse to claim his scalp like a proper Indian, Amalia was astonished when Rufus laughed off his mortal injury. With the strength of twenty men, her erstwhile prey became her captor, carrying the adventuress off into the night.

Rufus was no mere human being—he was a Gangrel, a kind of European vampire; a neonate exiled to the New World after a failed rebellion against the Camarilla in Lyon. Because his blood-brothers couldn’t bring themselves to execute a once-beloved comrade, they placed Rufus in torpor and exiled him to Nouvelle-France. Once in the New World, he proved even more feckless than before, working for the English and feeding from their population of enslaved Africans. He actually allowed himself to be caught for the foxhunt, believing it would be an amusing diversion. But when he realized that his hunter was a “fallen woman,” he knew immediately what must be done. Using her discharged shotgun as a cudgel, Rufus had his way with Amalia, then Embraced her and tossed her into an open grave. After shoveling in a few mandatory scoops of earth, he abandoned his unborn progeny and set off for New Orleans. He made it as far as Texas, where he was torn apart by a pack of Black Spiral Dancers.

Amalia survived her Embrace, emerging a few nights later in a feeding frenzy that claimed numerous wild and domesticated animals, a pair of French children picking flowers, and an escaped slave hiding in a canyon along the Sainte-Anne-du-Nord. It took her months to control her hunger, let alone her new Gangrel body, which had the power of shifting into bestial forms. Once her wits had finally returned, she understood that the only reasonable course of action was to depart the confines of civilization. While not exactly remorseful over her killing spree, leaving a trial of dead bodies was hardly conducive to her continued survival. And anyway, she had always wanted to see the Pacific Ocean.

Amalia wandered the interior for years, gradually heading west and taking pleasure in her new abilities. When life in the wilderness became too lonely, she’d haunt villages and settlements, keeping abreast of politics and sometimes making contact with the voyageurs, Indians, and trappers. The longest she remained in civilization was a few years spent in St. Louis, where she fell in with a Lasombra named Estevanico de Niza. A Spanish-speaking Moor who once accompanied Coronado, Estevanico introduced Amalia to contemporary Cainite culture, helping the fledgling understand her proper place as a “Caitiff Gangrel” and providing a vampiric vocabulary to help navigate her posthumous existence. When Estevanico decided to return south, Amalia continued her journey, following the trade routes into the “Inland Empire.”

In 1809, Amalia came across a beautiful young Kootenai named Sulee, and was inexorably drawn to the mysterious sauvage noble. She continued to stalk the maiden, and after nearly killing her in a state of frenzy, transformed her into a ghoul. Amalia took up the rôle of seductive monstress with a sense of self-discovery she found exquisitely liberating—the lust, the horror, the transgression, the sheer pagan joy of it! This connection to Sulee brought Amalia into contact with Xuma. Unbeknownst to the Kootenai couple, their first months together were shadowed by the Gangrel, whose initial jealousy transformed into delight the moment she realized the Sapphic nature of their relationship.

Once the couple reached Fort Astoria, Amalia become bored, and decided to make her way to the Orient. Traveling south, she found herself troubled by dreams of Sulee. By the time she arrived in California, she realized that something was calling her back to her first and only ghoul. With preternatural speed, Amalia traveled across the wilderness, but was too late to stop the hail of arrows that ended Sulee’s life. She could, however, do something about Xuma, who was bleeding to death over her dead lover. As she had once before, Amalia Desmarais surrendered her blood to save another’s life.

Amalia Desmarais (1756)

Xuma la Goule

Xuma awoke in a canvas tent, her naked body covered with scars and her limbs restrained by leather thongs. A white woman was kneeling over her, regarding her with curious golden eyes set into an attractive leonine face. Greeting Xuma with a smile, the woman revealed a pair of gleaming fangs. Her voice breaking, Xuma croaked, “Hello monster.”

The following week was difficult for both Gangrel and ghoul. Amalia confirmed that she was indeed the “monster” who had given Klaúwampatki her powers, and announced that Xuma would now take her place. Too bereaved for amazement or gratitude, Xuma begged to join her wife in death; but Amalia was intrigued by the tribade shaman, and refused to grant her suicidal request. It didn’t help that Xuma insisted on slashing her thighs from grief—Amalia had to hold back a frenzy on several occasions, drinking only enough blood to curb her hunger and licking closed the wounds. As Xuma emerged from her grieving, she regained her sense of self-composure, and demanded to be liberated from her bondage. To Xuma’s surprise, Amalia agreed; and to her greater surprise, she found herself returning to Amalia’s tent night after night. And not just for more “blood medicine,” either—but for companionship.

Bound by Kindred blood and their shared love for Sulee, Amalia and Xuma grew closer. Xuma’s French was certainly better than Amalia’s limited Ktunaxa, but during their feeding ritual, very little language was required. One night Xuma attempted to transform the ritual into something sexual, but Amalia gently refused. She found the Kootenai attractive, but sex was a path to frenzy, and Amalia had no desire to recklessly slay another lover.

And then Amalia was shot in the face by an English hunter. It was not an accident; Amalia had lunged for his throat with the intention to devour his blood. It was, however, a grave miscalculation. Having just heard him fire his gun at a bird, she assumed it remained unloaded. But the man was carrying a double-barreled shotgun. Her mangled face a disaster of blind flesh, Amalia managed to kill the tenacious hunter despite being stabbed several times by his hunting knife. Crawling back to Xuma, she informed her ghoul that she’d be forced to spend the next few months healing—a state she called la torpeur. Despite her wretched appearance, Amalia’s body could repair itself; something similar had happened to her after she was attacked by a pair of starving wolves near Fort Gibraltar. All she needed was a safe place to rest and a steady supply of blood. Xuma led her to a small cave secreted behind a waterfall. Exhausted and lapsing into torpor, Amalia instructed Xuma to visit her nightly with offerings of raw meat. In order to remain Amalia’s goule, each week Xuma should cut Amalia’s flesh and drink some medicine—but only during daylight hours. After a couple months, Amalia would emerge “as good as new.”

A couple months turned into ten years. Still little more than a fledgling, Amalia grossly misjudged the amount of time required for her body to repair itself, particularly given the dearth of Kindred blood and the attentions of a thirsty ghoul. Xuma grasped the situation rather quickly, bringing the dormant Gangrel monthly offerings of red meat and small animals. This was always done at a respectful distance; she had no intentions of ending up like that fawn she tied to a stake at the end of the first year.

During this time, Xuma continued her work. Now empowered by Amalia’s Gangrel vitae, she discovered that she’d inherited Klaúwampatki’s supernatural powers, and rumors began circulating around the native population that grief had granted the títqattek shaman a form of spiritual protection. Xuma began taking riskier missions, whether acting as a courier for white traders, traveling to distant reaches to share her prophecies, or acting as a negotiator between various warring tribes. She became involved in the Prophet Dance movement. She took new lovers and consorts. Life went on.

In 1837, Kaúxuma Núpika was attempting to broker peace between a friendly Salish tribe and a band of treacherous Blackfeet. Ambushed by the hostiles, she was stabbed several times—and to the amazement of all, her wounds miraculously healed! Attempting to overcome her supernatural prowess, the Blackfoot warrior finally opened Xuma’s chest with his knife and prepared to tear out the prophet’s heart.

Once again, the potential death of her only goule penetrated the haze of Amalia’s consciousness. Receiving premonitions of Xuma’s demise the day before the fateful blow, Amalia roused herself from torpor, devouring fish, worms, and insects as she waited for sunset. The moment it was safe, she launched herself from the cave, shifting to panther form as she raced towards the imminent battle. Leaping upon the warrior’s back, she tore his head from his shoulders and placed her jaws over his spouting stump. Engorged with human blood, Amalia turned to Xuma as the Blackfeet fled howling with fear. Xuma was a powerful warrior, and her ghoul’s body refused to give up—even though the Blackfoot had hacked opened her chest, her heart was still beating. Amalia slashed her wrists and poured her vitae directly onto Kaúxuma Núpika’s exposed heart. Little did she know it was a time-honored method of Embrace in the early Sabbat.

The Gangrel Fledgling

Despite a decade of caring for her dormant partner, the first months of their new relationship were not easy for Xuma, and she found it difficult to understand exactly what she had become. Was she now a monster too? Was she dead? A ghost? Restricting her diet to animals, she attempted to understand Amalia’s instructions, but became wrathful when her Sire limited her contact with other humans. Amalia forced Xuma to abandon her friends and lovers without so much as a hasty farewell. “They hunt us, you know. Your people and my people alike. On that much they agree. In time—sooner than you think—you will view yourself as apart from them.” For all intents and purposes, Xuma died that evening under the knife of the Blackfoot warrior.

As usual, Amalia was right. Her Cainite blood transformed her spirit as well as her body, and it became increasingly hard to fret about mundane concerns while stalking through the forest as a panther. Forced to sleep during the day, Xuma watched as the Dark Land faded from view. Was she no longer a seer? And did that matter, now that she was immortal? How much else would she sacrifice for this new life?

They finally had sex five months after her Embrace. It was after a successful hunt, bringing down a caribou and sharing its warm, sweet blood. The moon was full, the night was warm, and they decided to wash their bodies in a local pond. Within moments they were entwined, kissing and biting and laughing. Accustomed to being the assertive one, Amalia was surprised at how quickly Xuma took the reins, pinning her down with her powerful muscles and fucking her with her leather godemiche. They curled around each other all day long, fangs embedded in each other’s thighs in a sanguine soixante neuf. Upon awakening, Xuma discovered that she had carved symbols into Amalia’s pliant flesh during lovemaking; and she could read them, interpret them, spin them into a narrative about future events. Unearthed by the potent combination of diablerie and sex, the Dark Land had returned—but in a strange new form, blood-dimmed and mysterious, its un-language flowing from her unconsciously in a stream of bizarre symbols.

The couple traveled together for years, enjoying their nomadic existence and feeding from humans only when necessary. Still, there their relationship contained an unspoken inequity, and it was not the usual imbalance between Sire and Childe. Amalia had fallen in love with her own progeny, viewing their life as an idyllic romance, a vampiric Adam and Eve in an ever-dwindling Eden of wilderness. Xuma, on the other hand, felt increasingly restless. While she certainly loved Amalia, her Sire’s idea of “paradise” felt more like a stockade. According to Amalia, there were entire cities out there, cities full of people! Thousands of people, more people than leaves in the forest; and boats the size of fortresses with trees on deck, and buildings that rose into the clouds, and trains—trains! Trains and boats that led to cities like New York and Paris and London. And more than that, more people meant more sex. Xuma was never one for monogamy, and for once her wife was the jealous one. Despite being a vampire, Amalia had Christian roots, and was not accustomed to sharing her lover with others.

In 1849, a group of Mormon pioneers came across the pair blissfully feeding from a downed buffalo near Fort Laramie. They were in half-human form, two feral monsters playfully tossing each other raw organs. The humans opened fire, and the Gangrel fought back savagely, killing the men in an orgy of violence. Amalia wanted to murder the women and children as well, but Xuma demanded they be shown mercy. In the standoff that ensued, a still-frenzied Amalia began slaughtering the prisoners one by one. With a single survivor remaining, Xuma swiped her claws across her lover’s face, and Amalia vanished into the night. Kaúxuma Núpika would never see her again. Encountering a band of Dakota Sioux, Amalia Desmarais was cornered on the Plains and burned alive. Yet again, Xuma seemed unable to predict the most tragic events that would befall her own life.

Mixie

The survivor was a sixteen-year-old British girl named Maxine Shaw. Xuma was not foolish enough to Embrace the wounded pioneer, but she realized the girl needed infusions of her blood if she were to survive, so “Mixie” became Xuma’s first ghoul. Traumatized by the experience, Mixie believed herself to be in hell, and the devil was—and she certainly didn’t see this one coming!—a sexually deviant Indian vampire who could turn herself into a monstrous panther. Over time, her shock and horror receded, and Mixie adjusted to her new circumstances. As her once-human blood acquired more of Xuma’s characteristics, Mixie discovered she no longer wanted to be rescued. For what, anyway? To live in some American desert, the umpteenth wife of a dusty old zealot?

It was Mixie who first initiated sex, and it was Mixie who first called Xuma “beloved.” The daughter of a self-professed Mormon “prophet,” Mixie was raised believing in the power of second sight, and had helped her father interpret visions using a peep stone made from a piece of Irish cromlech. Soon Mixie took an active role in interpreting Xuma’s dreams. Mixie could feel the un-language written upon her skin, and with just a gentle stroke, she could close off unproductive passages and illuminate new pathways from the chaos. By 1855, they had become inseparable: vampire and ghoul, captor and captive, oracle and interpreter.

Kaúxuma Núpika and Maxine Shaw continued wandering the diminishing west, occasionally taking human lovers and sometimes walking the Spiral of Osiris. As time passed, Xuma watched all her old prophecies became fulfilled. She was wrong only about the timing—the Apocalypse did not happen suddenly, like the old tale of the moon crashing into the earth. The Apocalypse arrived in bits and pieces, treaty by treaty, betrayal by betrayal, one death falling upon another in a measured rain of ashes. Her people were placed in reservations, their lands taken and their once-proud distinctions blurred across tribal lines. Kootenai and Salish, Chinook and Kalispel, even Blackfoot—in the end, the white man saw little difference. There were times when Xuma was tempted to enter the struggle, but in truth, she stopped seeing herself as “Kootenai” even before she stopped seeing herself as “human.” By the time the War came, there was precious little wilderness left. The lovers departed the shipwrecked States for the city of Montréal, reportedly a haven for creatures like themselves.

Amandus of Metz

In Montréal, Xuma was introduced to Amalia’s grandsire, a Merovingian Gangrel named Amandus of Metz. Living in Canada since 1860, the elder was thrilled to meet this curious Indian Gangrel, the last survivor of his line in the New World. Detailing his family history, Amandus explained that his age granted his blood a remarkable potency, and his bloodline still carried traces of the Original Lineage before the clans of the Camarilla were officially recognized in 1111 AD. This is likely the reason that Xuma retained her magical powers when she was Embraced—in a very real way, she was part Tremere. Now a cardinal in the Sabbat, Amandus welcomed Xuma and Mixie into the sect, explaining their struggle with the Camarilla and promising to develop her powers as an “oracle.” The couple agreed, and Kaúxuma Núpika was officially inducted into the Montréal Sabbat on April 31, 1876.

Montréal Harbour 1870

Xuma

Xuma was not expecting to spend a century in Montréal, but she found the Sabbat to her liking—they were the only family, tribe, or group that allowed her to be herself. The Sabbat respected Xuma, appreciated and even needed her, and placed a high value on her oracular pronouncements. After Amandus returned to Europe in 1911, Xuma joined a coven led by his French packmate, Grenadier Toil. A Toreador antitribu in the process of becoming a Daeva, Grenadier was a pansexual neonate with an interest in erotic magic; Xuma found him to be the most fascinating male she had ever met, and he soon joined Xuma and Mixie in a variety of productive—and exhilarating—rituals. Familiar with a coven of Tremere antitribu, Grenadier introduced Xuma to Cainites who helped her refine her oracular abilities. Although she never fully trusted the Tremere, they gave her a coherent framework for her Dark Language, and she gained some fluency with Enochian magic along with the languages of Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Arabic.

In 1956 Xuma was taken to the Engulfed Cathedral to meet Paramándala Voin. To her amazement, La Reina Bruja addressed her as “Rain of Ashes,” her whispered words filling one ear with Spanish and the other with perfect Ktunaxa. Awestruck by the monstrous being before her, Xuma braved a question—“My visions. Where do they come from?” La Reina Bruja chuckled, a terrible, raspy sound in the dark. “Not the spirits, Gangrel. You were not meant for this world; you belong to another. Your soul was displaced by the Irruption. Your visions are the rotting language of another reality. With every prophecy you utter here, a door slams shut elsewhere. You speak the un-language of pandemonica, and your translations are destroying another universe.” Shaking with the mysterious truth of her words, Xuma cleared her throat to ask another question; but the interview was over, and something slithered across her parched lips to seal them shut. “You will make a fine oracle. Until, one day, you will speak the book of your new language, and the Apocalypse will destroy your true home. Then you will take your final name.”

In 1920, Grenadier Toil relocated to the United States to help Venus and Orchid found the Byzantium Coven. Xuma and Mixie remained in Canada, and spent the next few decades serving the Montréal Sabbat. In 2003, the Latrocinium Council decided that the Byzantium Coven needed an oracle. Concerned over the increasing “Cult of Venus,” Cardinal Lilitu and Bishop Malachi came to a rare moment of complete agreement—the Byzantium Coven needed an oracle unconnected to the Daeva, one whose magic was not based in Western tradition. Although Xuma was not the most powerful oracle in the Sabbat, the sexual nature of her magic made her a natural choice, and Venus accepted her presence with good grace.

Current Role

Today, Xuma and Mixie live in Club Byzantium, where they share a luxurious suite in the fifth-floor Magnaura. Having become accustomed to city life, the pair nevertheless take pleasure in Byzantium’s rooftop garden, and Xuma has emerged as its de facto caretaker. In one of her rare attempts at humor, Xuma jokes that she’s not sure which stereotype is to blame—being an Indian or a Gangrel. Unlike most Sabbat oracles, Xuma cannot be consulted by the coven over specific questions, and reports to Venus only when she’s had a vision.

Xuma still misses Montréal, and keeps in close contact with Amandus of Metz, her highly-placed patron in the greater Sabbat. While Xuma gets irritated by Venus’ constant attempts to “understand” or “define” her sexuality, the pair are fairly amicable; the Vicar has stopped believing that Xuma is a Montréal spy, and Xuma has stopped believing that Venus is pretending to be a goddess. Still, the coven has yet to feel like home. While she knows Sister Elsie Toshiro from her time in Montréal, she has always distrusted the assassin, and most of the other members of the coven strike Xuma as vain, frivolous, or insane—or a combination of all three. The only one she genuinely likes is Ingo Wallrafen, who reminds her of Robert Pettigrew. Outside of Byzantium, Xuma enjoys the company of Spiral, a fellow Gangrel who shares many of her own perspectives on the Sabbat.

As Xuma becomes more integrated into the Gotham Sabbat, she has begun to puzzle over the words of Paramándala Voin. A half-century has passed since she first heard her unsettling whispers, and since then no one has called her Rain of Ashes. But lately, the Dark Land has developed new territories, her nightly visits bringing her to the shores of a vast ocean glowing with a mysterious black light. In the distance, she can barely discern something coming closer—something very much like a tall-masted ship. Until now, Xuma has never seen any signs the Dark Land was inhabited by anyone but herself. Whether or not this mysterious ship carries a captain or crew is yet unknown. But it is clearly coming for her. And also? Lately she’s been hearing a new name floating on the wind, carved into the flesh of her lovers, and coalescing from the symbols of un-language. Is this the name foretold by the Witch Queen?

What does it mean to be a “Reckoner?”

Notable Cambions

Maxine “Mixie” Shaw

Although Mixie has spent the last century and a half as a ghoul, she shows no desire to be Embraced, and has developed into a unearthly creature as strange and beautiful as any Cainite. Willowy and blonde, her wholesome features still carry the echo of her pioneer past. She dresses in simple clothing and wears only one item of jewelry, a turquoise necklace made by the Métis and said to bring “good fortune.” She speaks Ktunaxa and English with a Quebecois accent, touched by a British diction inherited in her youth. Reserved in conversation, in bed Mixie reveals an almost psychic ability to please her partner, and her dedication to Xuma is complete.

Sources & Notes

Notes on the Characters

Kaúxuma Núpika is loosely based on a Kootenai figure mentioned in numerous journals from the early nineteenth century. Wherever possible, I used historical records and contemporary scholarship to recreate Xuma’s human life; but as one might imagine, most biographical details about Kaúxuma Núpika have gone unrecorded. Her first name as “Rain of Ashes” is my own invention, inspired by tales of a volcanic fallout that blanketed the region in the late eighteenth century. Kaúxuma Núpika did have a brother, and according to tribal lore, he acted in the manner described above. I fictionalized his name, along with the other details about Xuma’s family. I also invented names for her wives and consorts. Much of Kaúxuma Núpika’s romantic biography is sketchy and contradictory, so I teased out a few coherent narratives and provided brief profiles for her lovers. Klaúwampatki is inspired by the legend of the “Returned Woman” found in that region during the mid-1860s. She was said to have returned from the dead, and was granted supernatural powers by a pair of monstrous animals. David Thompson, Finan McDonald, and Augustin Boisverd are historical; however my characterization of Boisverd is entirely fictional—his name is known to history primarily because of his relationship to Kaúxuma Núpika. Estevanico the Lasombra is also based on an actual person, who indeed accompanied Coronado, but was reportedly killed by natives. All other characters are fictional.

Sources

The vast majority of information about Kaúxuma Núpika comes from “The Kutenai Female Berdache: Courier, Guide, Prophetess, and Warrior,” a paper written in 1965 by Claude E. Schaeffer and published in Ethnohistory, Vol. 12, No.3, pp. 193-236. Schaeffer’s paper synthesizes and correlates numerous historical accounts and contemporary research, from the journals of voyageurs who met Kaúxuma Núpika to academic papers written about the Plateau Indians. Schaeffer also conducted interviews with Kootenai who related oral tradition passed down from the early eighteenth century. Schaeffer’s paper also gave me inspiration for the “rain of ashes” and introduced me to the story of Klaúwampatki.

The following additional sources were also extremely useful:

Manning, Cynthia J. “Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians” (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers, 5855. This paper provided most of the background on the Kootenai and the other tribes of the region.

Nisbet, Jack. Sources of the River: Tracking David Thompson Across Western North America. Sasquatch Books, 2002. A book about Stargazer, it devotes several pages to Kaúxuma Núpika; however it’s clear that Nisbet is simply paraphrasing Schaeffer’s 1965 paper.

Vibert, Elizabeth. “The Natives Were Strong to Live: Reinterpreting Early-Nineteenth-Century Prophetic Movements in the Columbia Plateau.” (1995) Ethnohistory, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 197-229. Duke University Press. Provided some information and context on the Prophet Dance and the general climate of spiritualism among the native people of the Pacific Northwest.

Williams, Walter L. “The Berdache Tradition.” From The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1986. Helped me with some of the Kootenai terms for gender diversity.

While there are several small pieces about Kaúxuma Núpika on the Web, most are easily traced back to Schaeffer’s paper. I made more extensive use of this entry on Finan McDonald at HistoryLink.org, and this article on the Kootenai located at Native American Netroots. I’d also like to mention Michael Punke’s book The Revenant and the amazing Alejandro Iñárritu film it inspired, both of which were on my mind as I wrote this piece. Michael Cisco’s kaleidoscopic novel Unlanguage also helped inspire the creation of Xuma, and I am indebted to Cisco’s delightfully bizarre work for my conception of the Dark Land and the un-language of pandemonica.

Images

The image I selected to represent Xuma is a modern photograph. I found it on a Pinterest site devoted to “Native American Models,” so it is of course unattributed, and I cannot find its duplicate. If anyone knows the identity of the figure or the origin of the photo, please let me know! The map of the “Kootenai Region” was borrowed from Cynthia Manning’s 1983 paper, “Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians.” The photograph of the Columbia River Valley was taken by Barry A. Taylor, and borrowed from his blog “Hiking with Barry.” Visit the site for some great photos of the region! The antique photograph entitled Kutenai Duck Hunter was taken in 1910 by Edward S. Curtis, and currently resides in the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. The photograph of Fort Astoria is a 1911 replica constructed for the centennial, and was found on Wikipedia. The painting I used to represent Amalia Desmarais actually depicts Jane Stanhope, the Countess of Harrington. It was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1778. I do not mean to imply a link between the Countess and Amalia—I just liked the portrait. The photograph of Montréal Harbour and Customs House is dated circa 1870 and was found on Wikipedia. The photograph standing in for Mixie was found on a historical photograph site years ago, but I have unfortunately lost the original attribution.

Notes on Gender & Pronoun Usage

Kaúxuma Núpika is an inherently interesting figure—a berdache, an explorer, a prophet, and a warrior. By Schaeffer’s account, she was also an opportunist, a liar, and was not particularly kind to her wives. Today, she is often claimed by the two-spirit community, and is widely considered to be a transgendered male. Therefore, when writing this fictionalized profile, I was faced with several decisions—how do I treat her sexuality? What pronoun do I employ? Do I call her “berdache” or “transgender?” In the end, my choices reflect several different elements. First and foremost, this is not a Wikipedia entry. This is a fictionalized version of an interesting but obscure historical character, one being absorbed into the horror-based gaming milieus of Vampire: The Masquerade, Werewolf: The Apocalypse, and Savage Worlds’ Deadlands. I filled in a lot of blanks, asking myself how would someone in this position possibly behave? What are the various forces surrounding them, and what would be their motivations for responding as they did or did not? This is one of the pleasures of writing fiction; you may connect speculative dots to reveal any number of fascinating portraits.

I believe that contemporary sensibilities should certainly inform historical fiction, but the forces of modernity and presentism too frequently conspire to create bad historical fiction. While I necessarily wanted to rise above nineteenth-century stereotypes of civilization, savagery, and sexual “deviancy,” I also wanted to avoid simplified modern narratives that reduce people to victims and victimizers and deny the agency of individuals. I think it’s important to consider the complexities faced by Kaúxuma Núpika on all sides. I wanted to look at her actions themselves, believing that she acted with as much agency as possible given the time and place. For instance, some modern accounts portray Kaúxuma Núpika as a transgendered native who was held in bondage and raped for a year by Boisverd; there is no historical evidence to suggest that Kaúxuma Núpika herself believed this was the case. In fact, the accounts of the Kootenai themselves suggest that she was frequently mocked by her own people, and left her tribe on her own volition. This doesn’t mean that the historical Boisverd treated her well, of course, and history is full of white traders taking Indian wives, only to abandon their native families after they’ve returned to “civilization.” As a fiction writer, one may spin the relationship between Kaúxuma Núpika and Augustin Boisverd in any number of ways. I chose one particular path, informed by historical remarks accusing Xuma of “loose” sexual behavior and casting the unknowable Boisverd as a sympathetic bisexual. Other writers are free to create different stories.

Finally, there is Xuma’s sexuality and gender. Today, it is likely Kaúxuma Núpika would be considered transgendered. She was born a woman, attempted to attract a male, married a white man, then proclaimed herself a male and took on multiple wives. However, she also claimed that magic had switched her gender, then went to great lengths to conceal this story, suggesting she knew it was untrue. So, was Kaúxuma Núpika transgendered, bisexual, or a lesbian? Was she deliberately telling falsehoods to explain or justify her lesbianism, or trying to explain her gender dysphoria using the cultural vocabulary of mysticism and magic? The fact is, no one knows; one may only speculate.

This leads us to the correct pronoun. Schaeffer, the Kootenai interviewed, and many historical sources refer to Kaúxuma Núpika as “she.” Most also use the catch-all term “berdache.” Several modern sources, particularly those examining Kaúxuma Núpika from a Two-Spirit or transgendered perspective, use “he.” There is certainly evidence to suggest this conforms to the historical wishes of Kaúxuma Núpika, who claimed to be male after the marriage with Boisverd was dissolved. I gave this some consideration, and in the end decided to retain the traditional “she” pronoun. My fictionalized Kaúxuma Núpika has survived to modern times, but has not exactly adopted the language of contemporary gender theory. She considers herself to be male in spirit and female in body, and has no desire to get a sex change, whether through modern medicine or Tzimisce flesh-crafting. She is only romantically attracted to women, but will have sex with men when required for magic ritual. I acknowledge that if the real Kaúxuma Núpika would have survived to this day as an immortal vampire, it’s just as likely “she” would be “he,” or possibly “zhe” or “they.” But the fictionalized character presented here has made a particular decision, one based in the century of her origin, the development of her arcane powers, and her identity as a Sabbat Cainite. And so, most of her Sabbat packmates consider Kaúxuma Núpika to be a “butch” lesbian. She herself prefers simplicity, and generally resists being labeled.

Author: Great Quail

Original Upload: 22 December 2018

Last Modified: 16 September 2019

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

PDF Version: [Coming Soon]