Pynchon Music: Tim Souster

A hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning

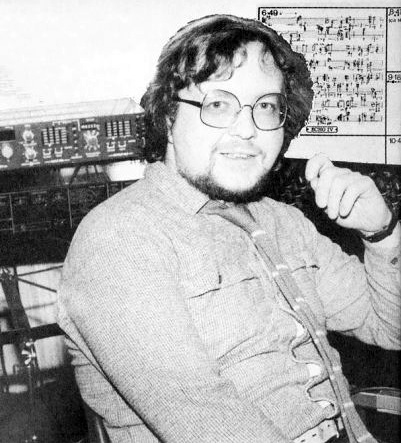

Tim Souster (1943–1994)

Tim Souster was a British composer who specialized in electronics. After studying under teachers influenced by Schönberg and Boulez, he became a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen, attending summer courses in Darmstadt in 1964. Returning to England, Souster was employed as a producer for the BBC. Working under the progressive “Controller of Music” Sir William Glock, Souster used his position to expose audiences to the musical avant-garde, from the thorny pieces of the Darmstadt School to the repetitive rhythms of American Minimalism. A fan of progressive rock, Souster saw numerous connections between “pop music” and “art music,” and he sought to bridge the two worlds through innovative programming and personal practice. In 1969 Souster invited Soft Machine to the BBC Proms, and his own avant-garde group, Intermodulation, worked with The Who. He also wrote articles and academic papers on musicians such as the Beatles, the Velvet Underground, Captain Beefheart, and the Grateful Dead.

In 1969, Souster produced his first electronic composition, Titus Groan Music. Inspired by the baroque fantasy of Mervyn Peake, the piece was scored for wind quintet, ring modulator, amplifiers, and tape. A few years later, Souster accepted a position as Stockhausen’s teaching assistant in Cologne. Returning to England in 1975, he continued his career as a composer at Keele University in Staffordshire. In 1978, Souster spent six months in California, working at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA, usually pronounced “Karma.”) In the 1980s Souster worked with the BBC again, scoring numerous films, documentaries, and television programs, including The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and The Green Man. In 1994, Tim Souster died of a “sudden, brief illness.” At the time of his death, he was composing a song cycle based on the poetry of Baudelaire.

Pynchon Connection

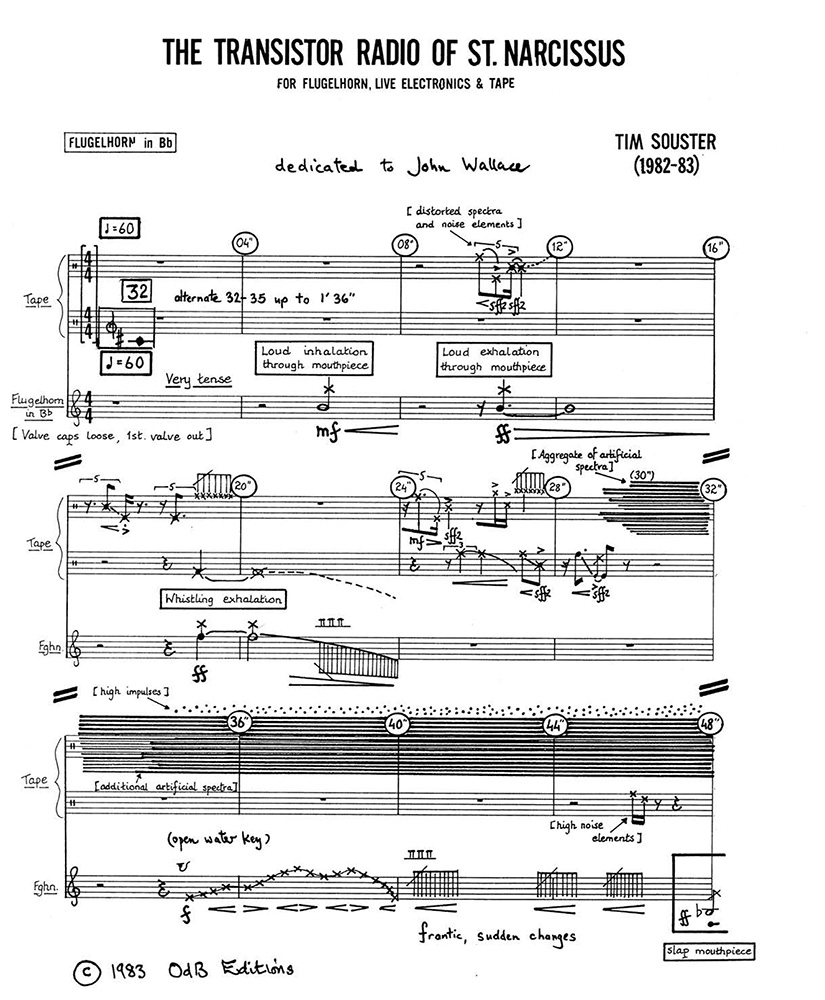

In 1983 Tim Souster composed The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus, a work for flugelhorn and electronics inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. While he wasn’t the first musician to be inspired by the novel, Souster had a pretty compelling claim to the book, as Pynchon mentions his mentor by name:

The Scope proved to be a haunt for electronics assembly people from Yoyodyne. The green neon sign outside ingeniously depicted the face of an oscilloscope tube, over which flowed an ever-changing dance of Lissajous figures… A sudden chorus of whoops and yibbles burst from a kind of juke box at the far end of the room. Everybody quit talking. The bartender tiptoed back, with the drinks.

“What’s happening?” Oedipa whispered.

“That’s by Stockhausen,” the hip graybeard informed her, “the early crowd tends to dig your Radio Cologne sound. Later on we really swing. We’re the only bar in the area, you know, has a strictly electronic music policy. Come on around Saturdays, starting midnight we have your Sinewave Session, that’s a live get-together, fellas come in just to jam from all over the state, San Jose, Santa Barbara, San Diego—”

“Live?” Metzger said, “electronic music, live?”

“They put it on the tape, here, live, fella. We got a whole back room full of your audio oscillators, gunshot machines, contact mikes, everything man. That’s for if you didn’t bring your ax, see, but you got the feeling and you want to swing with the rest of the cats, there’s always something available.”

One of the figures included on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was something of a cult figure, a musical and cultural iconoclast who was never shy of publicity—or controversy. While his music pushed the avant-garde as far as it could go (extreme electronic distortion, punishingly long durations, using helicopters as musical instruments) it was Stockhausen’s personal life that drew the most attention. He created his own musical utopia in the German countryside, an isolated compound where he led a polygamous life and worked obsessively on Licht, a week-long opera. He also claimed to have extraterrestrial origins, and famously described the 911 terrorist attack as “the greatest work of art that is possible in the whole cosmos,” despite its “criminal” failure to inform the audience they’d be “dispatched into eternity.”

Musically, Stockhausen was best known for incorporating modern technology into contemporary “classical” music. While he had the same fondness for dissonance, aleatory composition, and musical spatialization as his Darmstadt colleagues Pierre Boulez and Luigi Nono, Stockhausen developed a passion for electronics that lasted until his death in 2007, and most of his best-known pieces contain electronic elements and electroacoustic manipulations. It’s this embrace of technology that most informs the work of his students, disciples, and admirers, and that includes Tim Souster and The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus.

Review: The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus

Electronic music is always a dicey proposition. A cutting-edge piece can become hopelessly outdated overnight, and the public has a low tolerance for technological obsolescence. Many pieces of “avant-garde” electronics have not aged well, especially to ears long accustomed to rock, where pioneers like Pink Floyd and Brian Eno—themselves influenced by Stockhausen—pushed the medium forward. While Luciano Berio’s tape manipulations were innovative in the 1950s, today they’re only mildly interesting, even a touch silly. On the other hand, Steve Reich’s tape loops maintain their original power. Even more unpredictably, sometimes a piece of electronic music endures precisely because it’s dated, its former novelty alchemized by nostalgia into naïve charm: think of Pierre Henry’s “Psyché Rock,” Ron Grainer’s original Doctor Who theme, or even Morton Subotnick’s Silver Apples of the Moon.

But every so often an electronic composition just works. Despite the dated medium and evolving musical expectations, the piece still evokes the sense of mystery, of otherworldliness, that first intrigued contemporary listeners. Perhaps it’s because our subconscious registers synthetic sounds as alien, creating a sense of disorientation in our lizard brains; or perhaps it’s a brush with the technological sublime. Or, to borrow a term from the 70s, maybe we feel a tingle of “future shock.” For whatever reason, electronic music can be vaguely unsettling; but also numinous and curiously alluring—there’s a reason it’s often described as “spooky,” “spacey,” “celestial,” or “hypnotic.”

The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus is such a piece; a vintage slice of 1983 that still retains its original power. While not a complete success, it works more often than not, and is surprisingly accessible for music so intentionally disorienting—to compare it to Stockhausen, it has more in common with the intriguing soundscapes of Freitag than the unlistenable “Strukturs” of Kontakte. Like most avant-garde electronics, St Narcissus rewards a close listen, and is best played at high volumes. The electronic textures demand a tangible sense of presence, and the extreme ranges in frequency and dynamics work best when filling a room.

Lasting 24 minutes with no divisions, The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus is appropriately scored for a flugelhorn and live electronics. (Sadly, a postal horn has less range!) While not program music per se, the piece was inspired by Oedipa Maas’ near-epiphany upon seeing San Narciso spread out like the circuit-board of a transistor radio:

St Narcissus begins with a blaring hiss of distortion, a tearing sound like the sky ripping open. Electronics twitter like startled birds, while a synthesized organ beams a sustained chord down from on high. After this dramatic introduction, the piece settles into a more contemplative mood, with eerie electronic swells and subterranean rumbles that bring to mind Vangelis’ opening to Blade Runner. It’s not an unwarranted comparison, as both works hover above a sprawling cityscape, and the mood borders on the apocalyptic. Three years prior to composing St Narcissus, Souster himself visited California. It’s reasonable to wonder how much of his own experience is reflected here; flying into San Francisco or Los Angeles can certainly provoke feelings not unlike Oedipa’s “odd, religious instant.”

The flugelhorn becomes recognizable two minutes in, beginning its extended duet with the electronics: long, plaintive notes drift through a shimmering field of twinkling chimes, staccato fanfares are submerged in reverb, and glissandos flutter like hovering rotors. According to Souster’s notes, a Fairlight CMI is used to create mirror images of the flugelhorn’s “matrix chords.” Meant to evoke the similarity between San Narciso’s cityscape and a radio’s circuit board, this doubling provides some structure to the piece, but it’s frankly too arcane to be immediately apparent. (Typical of the Darmstadt school, Souster’s notes for St Narcissus read something like a math puzzle.) What’s more comprehensible, however, is the sense of impending revelation expressed by Oedipa, “As if, on some other frequency, or out of the eye of some whirlwind rotating too slow for her heated skin even to feel the centrifugal coolness of, words were being spoken.” The music seems continually poised to reveal something; an opening up, an unexpected melody, a satisfying resolution. Some kind of answer to this restless musical questioning.

Our answer comes 17½ minutes into the work, but it’s quiet, almost whispered. After pressing through a cascade of rippling brass, we find ourselves in the tranquil eye of the whirlwind. The flugelhorn unveils a simple seven-note melody, quietly repeated and developed over an undulating drone. Beautiful, mysterious, and delicate, it’s all-too brief. In the most striking moment of the piece, the understated melody drops away, the sudden silence filled by the sound of the player breathing through dead brass—a potent reminder of the “soft machine” behind the electronics.

The coda begins in a swirl of hissing static and chirping electrons, a walking bassline building suspense as we depart the serenity of the eye. The flugelhorn reappears, hesitant at first, unwilling to return to the maelstrom: but soon it’s back to its old tricks, with fluttering glissandos and peals of brass echoing off the staggering electronics. Sporadic drumbeats appear, and the synthesized bassline escorts the piece to its conclusion—a curt dismissal by a sharp downstroke.

Unfortunately, this four-minute coda prevents St Narcissus from achieving greatness. Much of the blame falls on the keyboards, which sound more dated here than anywhere else in the piece—the coda wouldn’t feel out of place in an early-80s Doctor Who episode. But this is superficial compared to the deeper problem, which is Souster’s need to resolve St Narcissus at all. Upon beholding San Narciso, Oedipa felt that a revelation “trembled just past the threshold of her understanding.” A better ending—or at least, a truer ending—would have forsaken the coda, allowing the horn to fall silent and the sound of beathing to fill the void.

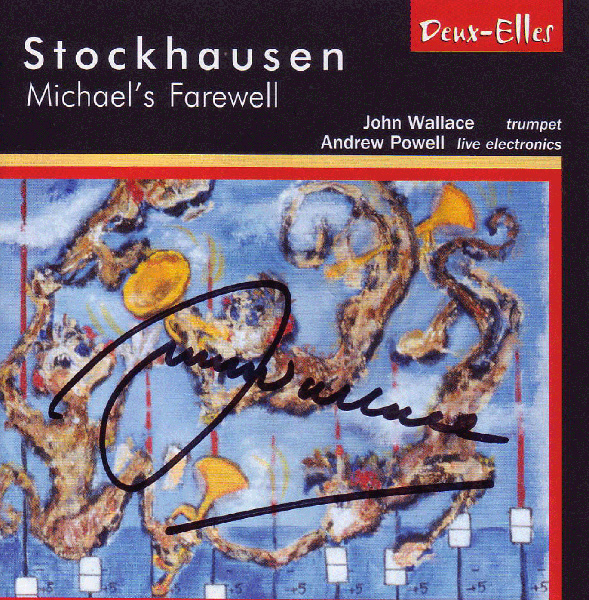

Despite this quibble, The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus remains a wonderful piece of electroacoustic invention, and deserves a wider audience. Unfortunately, the only recorded version is on the now-deleted Michael’s Farewell CD (Deux-Elles, 2002). For those listeners unwilling to dig through used record bins or enjoy the dubious pleasures of eBay, digital versions are available at Classical Archives and at John Wallace’s homepage.

Program Notes

For flugelhorn, live electronics and tape

- Fairlight CMI

- Roland Jupiter 8 synthesizer

- Roland MC4B micro-computer

- Roland Vocoder Plus

- Serge Modular System analogue synthesizer

- Lexicon Prime Time digital delay line

- MXR pitch transposer

Additional Information

2. Roger Smalley: Echo III (10:48)

3. Tim Souster: The Transistor Radio of St Narcissus (24:08)

4. Michaels-Abschied (12:47)

Andrew Powell—electronics.

John Wallace—trumpet.

Pynchon on Record

Return to the main music page

Last Modified: 23 November 2020

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com