Of course, Bigfoot operates in the straight world, so his means of coming to terms with his personal unfinished business involves sketchy plots, heroin smuggling, and manipulating Sportello, who is still just a disposable hippie freak, while Bigfoot is a respected police officer. The climactic scene of this parallel in the movie is one of Anderson’s more daring divergences from the novel, bringing out a kinship between the two men, when Doc and Bigfoot, two ships carrying breakable cargo, get completely in sync and speak together:

This shared dialogue is again word-for-word from the novel, but Anderson re-jiggers the context and speakers and adds a brief coda from later in the novel, making it between Doc and Bigfoot (Phoenix adds tears of recognition here, a beautiful and strange choice, but one that fits in that the hunkering suspicion that he and Bigfoot are closer in spirit than either want to admit). The movie, after Bigfoot takes a hit of Doc’s joint (“give it to me”—almost a sexual come-on) and then proceeds to eat his stash:

Bigfoot: I’m not your brother.

Doc: No, but you could use a keeper.

Which is a cut-up of a later scene in the novel where Doc and Denis share a joint and Doc realizes that Bigfoot was tailing his planted heroin transaction, still on his (futile?) quest to avenge his partner’s death. Is there an end to these missions to right wrongs? Doc worries about Bigfoot’s safety:

“Here,” Denis said after a while, passing a smoldering joint.

“Bigfoot’s not my brother,” Doc considered when he exhaled, “but he sure needs a keeper.”

“I know. Too bad, in a way.”

This re-contextualization of two scenes from the novel and adding another beat (Bigfoot eating the weed—was this improvised by Brolin? Which would make Phoenix’s tears even more interesting. Pynchon gets Bigfoot and Doc in sync with Doc’s attempt to gift Bigfoot the apparently fraudulent Wyatt Earp Mustache Mug) displays an affinity with the source material by bringing out a subtext throughout the book—that Doc and Bigfoot are sides of the same coin—and creating a new scene that underlines that subtext while being a true creation of that adaptation. At one point in the novel, Doc remembers “Time was when (he) used to actually worry about turning into Bigfoot Bjornsen…. opaque to the light which seemed to be finding everybody else walking around in this regional dream of enlightenment…” Added to the choice to have Bigfoot (finally) get stoned to get on Doc’s level (Doc’s many journeys into the straight world of police stations and court rooms might be the equivalent), Anderson manages to add a layer of complexity to his characters while straying from his source material, without betraying it.

Even though Anderson’s filmmaking has matured to such an extent that he has absorbed his influences—as opposed to intertextually highlighting them via compositions—he mentioned some of the direct influences on Inherent Vice during his press tour. One of his oft-cited references is Howard Hawks’ adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep. A classic noir/star vehicle for Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, its reputation lies with a plotting so convoluted that its three screenwriters (including William Faulkner and Leigh Brackett) were rumored to not really know what the plot was. The film is all about the star power—Bogart’s classic Phillip Marlowe smoking and drinking (Marlowe’s vice of booze as prevalent as Doc’s weed smoking) his way through various femme fatales and dangerous mobsters. But after a while, it doesn’t matter where Bogart’s leads lead, it’s the journey that makes the film. The plot twists pile up until the plot becomes secondary to the more important pursuit of atmosphere.

Plot secondary to atmosphere—the labyrinthine twists of The Big Sleep (1946) come to a head for Humphrey Bogart’s Philip Marlowe.

It’s a rare film that forces the viewer to give up in a sense and go with the flow, and this stoned quality appears to be what drew Anderson to it as a source for his Inherent Vice. There are at least five plots swirling around Doc, and all seem to be connected to that fateful night when Shasta returned to him. What was she really doing there? Did she really need Doc’s help or was she using him? And if she was using him what did that mean about their relationship, their love? And if Doc’s true love could be called into question, then it seems everything could be on the table, and potentially connected—if the positive vibes associated with love led to some sort of bliss (leaving off the square’s additive of “marital”), then what would the opposite be? Doc’s journey in both the book and the movie contain the convoluted layers of atmosphere Hawks plied on (interestingly The Big Sleep is missing from Doc’s repertoire of cinema—he’s much more of a John Garfield man), but Anderson one-ups Hawks by delving into some of Pynchon’s more serious thematic concerns along the way: What does it all mean, and what of it is worth doing?

What’s also interesting is what Anderson decided to include in his adaptation and what he left out—mainly for reasons of space (it appears). The released film clocked in at just under two and a half hours—definitely on the beefy side for a feature. The novel’s road trip to Vegas was completely omitted, as was Doc’s interaction with Tito the limo driver, and some minor though important characters—Boris and Dawnette Spivey, Trillium Fortnight, Einar (Puck Beaverton’s lover), and Fritz and Sparky (including their utilizing the pre-Internet ARPAnet). In the novel, Doc sees Mickey Wolfmann in Vegas with the two Feds we met earlier in the novel and film. Since Anderson needed to omit the Vegas trip, he places Wolfmann in the Chryskylodon asylum (also moving Doc’s mental “what the fuck” to Coy Harlingen’s silent mouthing—Coy is seen in the asylum in both the film and novel) and allows for a meeting between Doc & Mickey not in the novel—where some of the info given to Doc by Boris can come directly from Mickey’s lips. These are surface-level changes, and all connected to the Vegas trip.

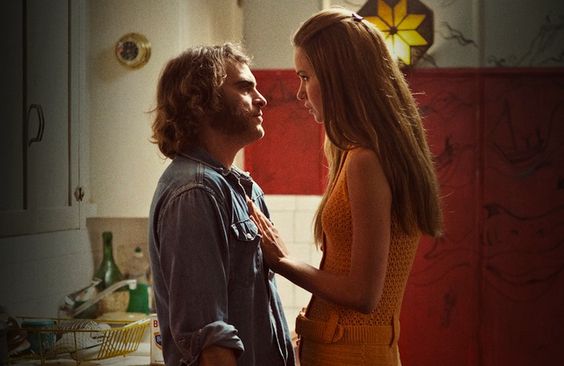

A more substantial change is the omission of Doc’s parents—who admittedly would feel somewhat out of place in the stoned noir mood of the film. In the novel, they serve to give Doc a sympathetic heart, that underneath the hippie is a good son who still loves his parents. Having Doc discuss getting his parents stoned would have sat uneasily next to the scene of Doc aggressively spanking(!) and having sex with Shasta, which does make sense contextually—Shasta becoming Doc’s shallow hippie fantasy instead of his true love—but seeing it played out on screen, especially with Joaquin Phoenix’s somewhat brutish take on Doc (more on that in a bit), makes it uncomfortable, one which seems to change the tenor of the rest of the movie. By removing some of the heart from Pynchon’s novel, Anderson takes his Inherent Vice into more cynical territory. This leads to one of his more noteworthy changes—that of the very end of the story.

The novel’s final pages are a brief and dreamy denouement. Doc is driving solo on the Santa Monica Freeway when a major fog sets in. He observes how his fellow travelers guide themselves through the fog by sharing each other’s headlights to their respective exits. Doc addresses the indeterminacy of life—his stoned demeanor accepting what lies under the identity-erasing fog, whatever it may be, and hopefully it’s something fortunate (“whatever would happen”). That there’s even the small possibility for magic under the fog of the day. The soundtrack is Fapardokly’s “Super Market,” Elephant’s Memory, the Spaniels’ “A Stranger in Love,” and that anthem to 60s nostalgia and love, The Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.” The songs set the scene.

Anderson had used “God Only Knows” in his things-just-might-work-out montage towards the end of Boogie Nights, and it makes sense for him to not want to repeat himself; but his changes to the ending reflect a creeping cynicism in Anderson’s post Punch-Drunk Love works (excepting Licorice Pizza which felt like his own light nostalgia trip as a response to Covid’s darkness): The drunken Plainview murdering Paul Sunday in There Will Be Blood, the Clockwork Orange-ish “I was cured all right” ending of The Master, and Woodcock submitting to the sado-masochistically controlled relationship in Phantom Thread. These are dark endings, not exactly celebrating the depths of depravity, but presenting an acceptance with a flawed humanity motivated by uncontrollable urges. People can be shit, which makes the world shit. Things weren’t so bleak in earlier films. The love of a makeshift family in Boogie Nights, Sandler’s Barry Egan finally giving into love at the end of Punch-Drunk Love, and even Melora Walters’ possibly breaking-character smile after three hours of torment at the end of Magnolia—these endings reflect a sense of inviting even the possibility of love—which could also reflect Anderson’s youth at the time of making the films. Pynchon in Inherent Vice seems to be tempering some of his more cynical inclinations throughout the novel, which feels like a love letter to his own younger self (he would definitely buy Doc a beer, as he mentioned wondering about his younger self in the intro to Slow Learner).

Anderson inverts the ending on two levels. His setup of Doc driving Shasta in his car at night starts off with Shasta commenting on Sortilege’s possible psychic ability, which could be Anderson’s tip of the hat to his making Sortilege the film’s narrator (as opposed to the omniscient narrator of the novel, which never leaves Doc’s viewpoint). The novel’s fog is missing from the movie. (Although the scene is shot too tightly to be certain; it could be foggy outside the car?) His first inversion comes from taking lines directly from an earlier scene in the novel (“This doesn’t mean we’re back together.” “No. No, course not.”) and swapping the speakers. In the novel, this immediately follows another round of Shasta/Doc coitus. Shasta tells Doc they aren’t back together, and Doc understands that it’s just friendly sex, not an invitation to love. In the movie, after Shasta feels that maybe Sortilege had been using her psychic powers to set them up in the first place, that she might know something about them they don’t know, that possibly they actually were meant for each other.

After the entire narrative leading up to Doc coming to terms with Shasta not being who he thought she was and possibly even putting his life in danger, it makes more sense for Doc to refuse the insinuation that they are meant to be, and Waterston—who goes from stoned/dreamy to sad throughout the scene—smiles at Doc’s recognition of the reality of their relationship. Doc looks in the rearview mirror as the reflection of the headlights behind catches him in the face. Someone might be following them. Love is for suckers, and better look over your shoulder as you don’t know who might be coming for you. The resolution of his relationship with Shasta is that the love he felt for her has now made him paranoid, and they might be actually out to get him. She has used Doc and put him in perpetual danger, maybe even brought him down to her compromised level, that of a world where you better get yours while you can because others won’t be waiting to take from you—a much different sentiment than the novel.

The second inversion plays into Pynchon’s nostalgia for, versus Anderson’s remote view of, the 1960s. In the novel, Doc is alone in his car, using the headlights and taillights of other cars to guide him through the fog: a “temporary commune to help each other home.” This is a much different note to end on than what Anderson conveys in his film. Though you can’t really blame Anderson for changing this—shooting a caravan on a highway in fog at night with the purpose of showing headlights and taillights as guides off an exit would prove to be an extremely complicated and tricky scene to pull off. (Though I’m sure Anderson could do it! Baumbach does something similar with the traffic jam out of town in White Noise, which reportedly had over four times the budget of Inherent Vice.) More to the point, it would go against the tone of the movie. Anderson was barely alive when the thrust of Inherent Vice took place, so Pynchon’s nostalgia for the 60s would be false for Anderson (he is two generations older—his WW2 “greatest generation” vs. Anderson’s Gen-X sensibility). His choice to avoid nostalgia might have played into his truth in telling this particular story, which also folds into some similar cynical thematic territory as his twenty-first century productions. With Inherent Vice, he is channeling another’s nostalgia that he cannot directly share, and views that hazy optimism with a dash of cynicism. (It makes sense that Anderson would explore his own sense of nostalgia more thoroughly with Licorice Pizza a few years after filming Pynchon’s callback to his halcyon days.)

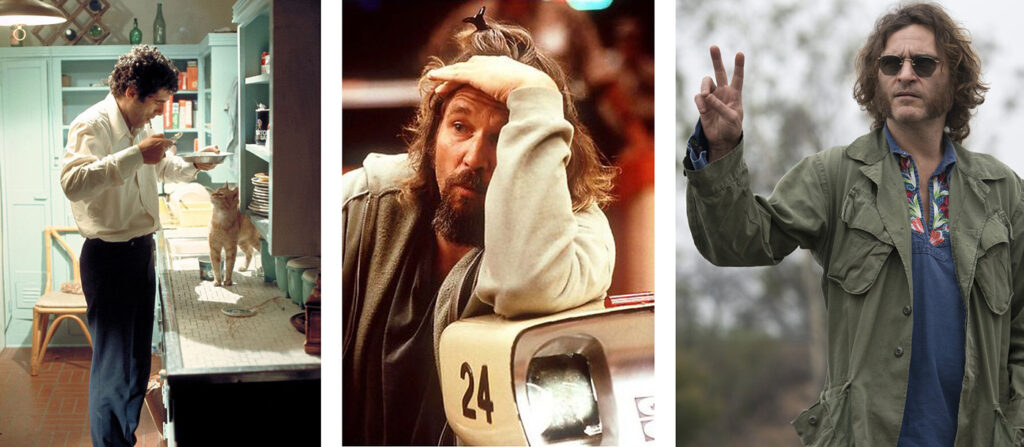

One of the trickier aspects of adapting Pynchon and Inherent Vice (and adaptations in general) is casting. Readers create the characters in their own minds and then casting an actor will forever change perceptions of said character. Anderson’s casting of Joaquin Phoenix as Doc is a bit of a mixed bag. Phoenix is one of the finest actors of his generation, and Anderson had previously presented him with the exemplary role of Freddie Quell in The Master, which played to all his strengths: a Brandoesque brute with a vulnerable, sensitive core, motivated by primal urges he can’t begin to explain or understand. He is. Immediately before Inherent Vice, Phoenix played the hapless Theodore in Spike Jones’ Her which showed much more of his vulnerable side. Doc Sportello would potentially allow Phoenix’s sillier inclinations to come to the fore, which audiences largely had not seen. He has not (to my estimate) gone cartoonish or silly in ways that some of Anderson’s other staple actors had—Philip Seymour Hoffman in Along Came Polly (even his roles in Hard Eight and Punch Drunk Love are broad), or John C. Reilly in Step Brothers, among other things. Josh Brolin seems to hit the right tone of cartoonish absurdity with his Bigfoot Bjornsen—though he had cultivated that as George W. Bush in Oliver Stone’s W. and the various Marvel films he’d appeared in (and brought out again in the Coen Brothers’ Hail Caesar). His scenes with Phoenix have some great comedic timing. Phoenix excels in the more serious, visceral scenes later in the film—the killing of Puck Beaverton and Adrian Prussia for example—but that tone of Pynchon goofiness seems tricky for both Anderson and Phoenix to nail consistently throughout the film. The result is a strange mixture of tone that veers drastically from freaky cartoonishness to sober realism on the shoulders of Phoenix’s somewhat cypher-ish portrayal of Doc. Anderson and Phoenix experiment throughout, and the film comes off as more intriguing than engaging, which benefits greatly from the viewer being familiar with the novel.

Experimenting throughout: Joaquin Phoenix and Paul Thomas Anderson on the set of

Experimenting throughout: Joaquin Phoenix and Paul Thomas Anderson on the set of Inherent Vice.

It’s a tricky balance not leavened by the poetic code of Pynchon’s writing—which Anderson samples throughout in the dialogue and in Joanna Newsom’s narration. Part of the movie’s inscrutability comes from Anderson’s direct use of Pynchon’s words in dialogue and narration. If the viewer isn’t familiar with the novel, much of this might sound like gibberish. (I thought of my father trying to follow Inherent Vice!) A recent watch of Christopher Nolan’s divisive Tenet reminded me of some of Inherent Vice’s dialogue. Nolan’s characters speak in a spy-code which does not directly relate to the on-screen action—“we live in a twilight world” of course pertains to the perception of the real world, but is used in the movie as the cue-in to others who are in on the covert machinations under the surface action. Doc gets a similar coded clue with “Beware the Golden Fang,” a seemingly nonsense phrase that potentially describes a boat, a building, a group of sinister dentists, and is the Greek translation of the asylum where Mickey Wolfmann winds up, as well as a reference to the legendary “Golden Triangle” in Southeast Asia – rumored to be the source of the heroin that made it to the states in the 70s. Just as in Tenet, it’s all connected, and if the reader or viewer becomes intrigued, they can follow these trails of connections off the page. Anderson succeeds in capturing that sense of Pynchon’s fiction as piercing reality (in the reader’s mind at least); that conversation he’s having with your brain during the reading/viewing of Inherent Vice.

“Beware the Golden Fang”—Doc justifiably paranoid by the heroin stash planted on him by Bigfoot Bjornsen.

“Beware the Golden Fang”—Doc justifiably paranoid by the heroin stash planted on him by Bigfoot Bjornsen.Pynchon’s prose is at once extremely specific and enticingly ambiguous (as Steve Erickson says in his intro to Zak Smith’s Pictures Showing What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow: “There’s not one Gravity’s Rainbow but thousands.”) A film adaptation is a puzzle without a solution, and for the foreseeable future Anderson’s approach will remain the Word on filming Pynchon. He handles that burden with a graceful touch, bringing beauty to the shores of Gordita Beach, and creating his own puzzle under the paving-stones and fog.

Soundtracks and Film-Novels

When Inherent Vice came out, Pynchon himself (supposedly) sent Amazon a playlist for the novel—songs that appeared in the narrative and would potentially make good reading music to capture the vibe of the time. Of course, some invented bands and songs made their way into that list. I loved this—time spent on iTunes (or whatever) stitching together this playlist added to the overall joy of diving into the novel, to hear the sound of this world. Vineland and Bleeding Edge were also chock-full of songs and movies and television shows, but Inherent Vice had the blessing of the pope as it were, giving the reader even more of the nostalgic texture of the time. Anderson jumped in with the trailer, using two period-correct tracks (Sam Cooke’s “(What a) Wonderful World” and Sly & the Family Stone’s “I Want to Take You Higher”) that added up to one of the most saliva-inducing promises of theatrical glory I’d ever seen. I’d put it up there as one of the best trailers in recent memory, alongside Sofia Coppola’s “Age of Consent” mood-setter in Marie Antoinette, and Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis—two minutes of electricity the entire 160 minute feature never recaptured. Anderson strays from Pynchon’s soundtrack almost immediately—yes, Can’s “Vitamin C” is a great song, but is maybe a year too early for period correct? But you know, even just saying that out loud seems like it would get a “fuck you” reaction from the creators. You know, the movie is NOT reality (“with an adjustment or two what the world might be”), and a great Can track from 1972 fit what Anderson was doing when Doc and Denis go to get pizza, foolish period accuracy be damned.

Inherent Vice’s soundtrack presents Pynchon’s sonic referents (especially post-Vineland) within his context—it’s not too much of a stretch to think that the author listened to the songs in his novel at least once, and probably had some affinity for them. It’s quite different from putting together a soundtrack for a feature film where those nasty things like performance and songwriting rights and money come into play. (Though of course a filmmaker of Anderson’s stature and history with re-contextualizing songs so that they become cool again—see “Sister Christian,” “99 Luftballoons,” “Let Me Roll It,” etc.—shouldn’t have too much trouble securing those rights.) Anderson has admitted that Neil Young’s movie and song “Journey Through the Past” was a key influence on his adaptation. The vibe of the song and the look of the film drench Pynchon’s words in a sense of nostalgia, which feels like a major throughline; the song capturing that halcyon sense of the early 70s (for Anderson) and its lyrics potentially piercing the referent veil for Pynchon—what is Inherent Vice if not a “Journey Through the Past?” I’m sure that other writers have created mixes to go along with their novels—Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad takes place in the late 90s world of indie and major label rock, but didn’t seem to quite indulge in the specific bands and songs that Pynchon did. More along the lines of Inherent Vice would be Steve Erickson’s Shadowbahn (which includes a mixtape from the father character to his daughter), or David Keenan’s Industry of Magic & Light (the first half of the novel is a character sifting through the contents of a caravan, which includes vinyl LPs).

Shadowbahn is the most explicit of using songs to convey a sense of the narrative—he’s looking for a lost America (potentially lost by the fall of the WTC in 9/11) via an alternate reality guided by Elvis’s dead twin brother Jesse. Interestingly, some of the dreamlike apocalypse mood of Shadowbahn would be captured by Scott Walker’s haunting song off The Drift—“Jesse,” also potentially about Elvis’s dead brother (missing from Erickson’s playlist but it doesn’t quite work in that context anyway). Erickson seems to be longing for America’s redemption—the central track to Shadowbahn’s playlist is Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman” with its eerily prophetic pre-9/11 lyrics “here come the planes.”

Pynchon isn’t necessarily trying to make those types of leaps of connection with Inherent Vice—his tracklist plays closer to Keenan’s also 1970-and-before period-correct songs in Industry of Magic & Light. Keenan was a music journalist and record store owner before becoming a novelist so it would make sense that the soundtrack to his novel would consist of extremely rare vinyl tracks that would be obscure “holy grails” to record collectors. He does slip in a fictional band from time to time (like Pynchon), but he gets so obscure that only the true heads (or those so inclined to investigate) would know that Zweistein’s Trip-Flip Out-Meditation is a real (and extremely rare) album from 1970. Keenan is actually about the same age as Anderson, but instead of Anderson’s side-stepping of nostalgia for a time he can never experience, Keenan seems to want to channel the spirit of the 60s wholesale through its detritus and Tarot cards—closer to Pynchon’s own mixtape of his past. Keenan soundtracks a sex scene to Black Sabbath’s “Planet Caravan” (which causes the narrator to avoid listening to Paranoid ever after), and his fighter Adam has a theme song that shifts from Frank Zappa’s “Trouble Every Day” to the haunting Blind Faith track “Presence of the Lord.” Listening to the tracks while reading enhances the trip, as it were. All three of these novels seem to be aware of the possibility of their readers’ ability to create playlists based on the songs catalogued within, as opposed to pre-download eras where (especially in Keenan’s case) tracking down the albums would cost a reader thousands of dollars. The authors seem to be giving their readers an invitation to listen—to step beyond the page and let their narratives soundtrack the world outside.

Similarly, Inherent Vice reflects its characters (and potentially its author’s) propensity for music, movies, and television by over-loading it with pop culture references. The Crying of Lot 49 is set close to the time it was written and has some direct references (Lamont Cranston, the Beatles, etc.) but not close to the volume of Inherent Vice. Doc is a John Garfield fan, the tragic star whose run-ins with HUAC contributed to his stress-related early death. Doc’s interactions with both Penny and Bigfoot could have some stoned correlation to John Garfield, or he could just be a fan of Body and Soul, They Made Me a Criminal, and Out of the Fog. Sloane Wolfmann in both the novel and the film drops that “Jimmy Wong Howe” did the lighting to her living room—allowing Anderson to both emulate Howe’s evocative toplighting and enjoy a reference to a cinematic obscurity that those who know would realize is a real cinematographer, whereas the bands Spotted Dick, Meatball Flag, and The Boards are fiction (though Pynchon does provide the lyrics for Meatball Flag’s “Soul Gidget” which could be spoofing the Doors “Soul Kitchen” or the Bar-Kays “Soul Finger”). In the novel, we also get references to the theme to Dark Shadows (and a discussion of parallel time from the show), Tiny Tim’s trippy “The Other Side,” and an obscure one-hit wonder in Bob Lind’s “Elusive Butterfly.”

“Do you like the lighting? Jimmy Wong Howe did it for us…”—Serena Scott Thomas as Sloane Wolfmann.

“Do you like the lighting? Jimmy Wong Howe did it for us…”—Serena Scott Thomas as Sloane Wolfmann.Pynchon including his own songs in his novels has carried through since

V.—all of Pynchon’s books are musicals in a way—but his soaking

Inherent Vice,

Vineland, and

Bleeding Edge in pop songs and cinema presented a way for other authors to explore their own cinematic taste in their fictions. David Foster Wallace’s filmography for James O. Incandenza in

Infinite Jest places his fictional filmmaker alongside real directors like Beth B., Fritz Lang, and David Lynch—pointing towards DFW’s fly-on-the-wall reportage of David Lynch making

Lost Highway in “

David Lynch Keeps His Head.” Steve Erickson’s

Zeroville cine-autist Vikar has

A Place in the Sun tattooed on his head, and knowledge of Dreyer’s

The Passion of Joan of Arc becomes integral to the story. (Not to mention the whole thing feels like it takes place within Peter Biskind’s chronicle of late 60s Hollywood

Easy Riders, Raging Bulls—which James Franco seemed to want to shit on with his, shall we politely say, experimental adaptation of Erickson’s novel, which misspelled Erickson’s last name in its trailer.) Other film-set novels include Marisha Pessl’s

Night Film, Theodore Roszak’s

Flicker, and Mark Z. Danielewski’s

House of Leaves (

The Navidson Record in approach resembles the

Blair Witch Project, which came out a year before). But where the film and novel of

Inherent Vice really found its truest literate-cum-filmic conversationalist was in Quentin Tarantino’s film and novel

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Quentin Tarantino is the seismic shift in Hollywood sensibility of the 1990s, to such an extent that the following ten years—especially in the indie realms—seemed to mirror what he was doing in both Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. It’s not a stretch that Anderson’s early career followed in the wake that Tarantino had laid out for him—Sundance darlings operating in the stylish black comic crime mode. David Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, and Steven Soderbergh had laid the groundwork for Tarantino to seize the day as it were—Blue Velvet and Mystery Train would make for a great triple feature with Pulp Fiction. All three films wrestle with 50s iconography and how it affects contemporary sensibilities—Bobby Vinton’s song still makes psychotic perv Frank Booth cry, Elvis appears to the stranded Italian tourist (and Clarence in the Tarantino-scripted but very Tony Scott True Romance) in Mystery Train, and Vincent & Mia go out to dinner at Jack Rabbit Slim’s—the ghosts of the 50s shape contemporary America. But Tarantino was the rockstar, achieving the European acclaim of Jarmusch (whose sensibilities have eluded major box office success or academy awards), the zeitgeist-shaping of Lynch (Twin Peaks taking over America’s subconscious for at least its first season), and the indie film David vs. Goliath success of Soderbergh, while making major box office inroads and Academy Awards. A cynic (or Peter Biskind) might look at Harvey Weinstein and Miramax’s hand in Tarantino’s ultimate success, but Tarantino would never have been Tarantino without the films.

His Once Upon a Time in Hollywood could take place in the same world as Inherent Vice, both convoluted re-imaginings of the transition from the 1960s to the 1970s, playing fast and loose with the facts but shrouded in the long shadow of Manson. It seemed somewhat strange for Tarantino to novelize his own movie but in reading it, it allowed him to dive further in the backstories of all the films and television series he’d created for the feature—the fictional 14 Fists of McClusky fits nicely next to the actual Lancer—and tell some of the Hollywood stories he’d amassed in his 30-plus years as a filmmaker. His analysis of the Manson murders—that Manson was ultimately saving face in front of his commune after being stood up by recording industry insider and songwriter Terry Melcher—allows Tarantino to present an insight into the murders missing from Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, though in hindsight Bugliosi’s reportage was so close to the actual killings he might not have been able to connect the dots with what ultimately set off Manson. (Tarantino has Tate listen to the Melcher-produced Paul Revere & the Raiders throughout his film.) Tarantino mourns the death of Sharon Tate and wants to rewrite history in his own histrionic way—you can almost hear his hyper-caffeinated enthusiasm discussing Tate with Roger Avary on their podcast and mourning her much-too-early death: You know what would have been cool? If the Manson Family stumbled into the wrong house and met a fucking flamethrower instead.

Tarantino and Anderson’s usage of pop songs ironically (or even sincerely) immediately points to Scorsese’s titanic influence on contemporary cinema—incorporating the Doors into Who’s That Knocking on My Door, and then of course dropping “Be My Baby” into Mean Streets and culminating in the era-spanning soundtrack of Goodfellas as an alternate history of 50s-70s America. Goodfellas’ resonance with Anderson—especially in Boogie Nights (and by extension Damien Chazelle in Babylon, whose film seems to lose its footing when it tries to ape the rock bottom sequence of Dirk Diggler—Anderson was basing his depths of depravity on the actual story of a dim bulb in way over his head with John Holmes; while Chazelle seemed to be basing his on Boogie Nights) comes out in the packed-to-the-gills Boogie Nights soundtrack which chronicles the changing times via song. It’s a cinematic shorthand to say where you are chronologically by having a needle drop convey it as well. (Of course, Anderson throws in the Easter eggs as well by having Mark Wahlberg sing “The Touch,” an obscurity from the Transformers movie soundtrack.) Pynchon’s usage is a bit more George Lucas in American Graffiti or Richard Linklater in Dazed & Confused—both chronicles of a single night in their respective period—a dose of nostalgia to jog the memory where the dope of the past might have obscured it.

In any case, Tarantino, Anderson, and Pynchon are looking back at the moment when free love gained its price tag, and Charles Manson ruined the hippie ideal for generations since, contributing skewed additions to the rich legacy of the LA crime film. Anderson channels some of the spirit of Pynchon’s novel, digressing from his source to compact the narrative, while retaining the elusiveness of the prose and the labyrinthine confusion of its plot. Just like the novel, the film teases the audience to keep returning, suggesting that with subsequent viewings, there is something to Inherent Vice; you just need to pay more attention—or listen closer to the soundtrack. Embrace what is not clear, as attuning your antenna to those higher frequencies might lead to clarity. Though of course, you might be planting it there, that meaning that’s sought, and what’s more substantial is the seeking. Just as Doc is hoping for something good to come out from under the fog.

“

This doesn’t mean we’re back together.”—Doc and Shasta Fay now forever looking over their shoulders in the concluding shot of Inherent Vice.

Playlist

“Elusive Butterfly,” Bob Lind

“Super Market,” Fapardokly

“A Stranger in Love,” The Spaniels

“God Only Knows,” The Beach Boys

“I Want To Take You Higher,” Sly & the Family Stone

“(What A) Wonderful World, “ Sam Cooke

“Age of Consent,” New Order

“Vitamin C,” Can

“Sister Christian,” Night Ranger

“99 Luftballoons,” Nena

“Let Me Roll It,” Paul McCartney and Wings

“Journey Through the Past,” Neil Young

“Jesse,” Scott Walker

“O Superman (for Massenet),” Laurie Anderson

Trip – Flip Out – Meditation, Zweistein

“Planet Caravan,” Black Sabbath

“Trouble Every Day,” Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention

“Presence of the Lord,” Blind Faith

“Soul Kitchen,” The Doors

“Soul Finger,” The Bar-kays

“Opening Theme from Dark Shadows,” The Robert Cobert Orchestra

“The Other Side, “ Tiny Tim

“Be My Baby,” The Ronnettes

“The Touch,” Stan Bush

Bibliography

Nonfiction

Fiction

Ballard, J.G.

Crash. Jonathan Cape, 1973.

Ballard, J.G.

High Rise. Jonathan Cape, 1975.

Durrell, Lawrence.

Justine. E.P. Dutton, 1957.

Erickson, Steve.

Zeroville. Europa Editions, 2007.

Erickson, Steve.

Shadowbahn. Blue Rider Press, 2017.

Gaddis, William.

J R. Alfred A. Knopf, 1975.

Herbert, Frank.

Dune. Chilton Books, 1965.

Joyce, James.

Ulysses. Shakespeare & Co., 1922.

McCarthy, Cormac.

Suttree. Random House, 1979.

McCarthy, Cormac.

The Road. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

O’Connor, Flannery.

Wise Blood. Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1952.

Pynchon, Thomas.

Slow Learner. Little, Brown & Company, 1984.

Pynchon, Thomas.

V. J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1963.

Pynchon, Thomas.

Vineland. Little Brown, 1990.

Roszak, Theodore.

Flicker. Chicago Review press, 1991.

Wallace, David Foster.

Infinite Jest. Little, Brown and Company, 1996.

Additional Information

Inherent Vice— You can rent or purchase

Inherent Vice from Amazon Prime.

IMDB Page — The Internet Movie Database features a profile of

Inherent Vice.

0

0  “You were always true”—Katherine Waterston’s Shasta Fay Hepworth puts Doc in a compromised position.

“You were always true”—Katherine Waterston’s Shasta Fay Hepworth puts Doc in a compromised position.

“Beware the Golden Fang”—Doc justifiably paranoid by the heroin stash planted on him by Bigfoot Bjornsen.

“Beware the Golden Fang”—Doc justifiably paranoid by the heroin stash planted on him by Bigfoot Bjornsen. “This doesn’t mean we’re back together.”—Doc and Shasta Fay now forever looking over their shoulders in the concluding shot of Inherent Vice.

“This doesn’t mean we’re back together.”—Doc and Shasta Fay now forever looking over their shoulders in the concluding shot of Inherent Vice.