Joyce Music – Boulez: Third Piano Sonata

- At June 22, 2024

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I have often compared this work with the plan of a city. One does not change its design, one perceives exactly what it is, and there are different ways of going through it. One can chose one’s own way through it, but there are certain traffic regulations.

—Pierre Boulez on the “Third Piano Sonata”

Troisième Sonate pour Piano

(1958 to never)

Formant I—Antiphonie (posthumous, includes “Sigle”)

Formant II—Trope

Formant III—Constellation/Constellation-miroir

Formant IV—Strophe (unpublished)

Formant V—Séquence (unpublished)

A musical labyrinth incorporating nonlinear design, performer-based decisions, and notions of form itself as a principle aesthetic, Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata represents a pinnacle of musical Modernism, an “open work” cast in ebony and ivory. Despite (or more likely, because of) this, the Third Piano Sonata is more often discussed than heard; and having spawned numerous essays, critiques, justifications, nearly-inscrutable liner notes, and snide post-mortems, it has produced more commentary than concerts. It’s also rather difficult to perform, requiring much preparation on the part of the interpreter in terms of organization as well as practice.

In part, the Third Piano Sonata arose from Boulez’s interest in literary Modernism, particularly as represented in works by Stéphane Mallarmé and James Joyce. Mallarmé offered the multiple fascinations with form as aesthetic, with his typographical effects drawing attention to the relationships between the printed words and the page containing them; and later, his belief that a book should contain a degree of reader-initiated indeterminacy. Although Joyce held similar views to the French poet, his ideas on language and style were taken to greater extremes. Finnegans Wake pointed the way to an open text, a cyclical work available for entry at multiple points. Boulez—always ready to overturn the old order in his quest for musical revolution—was intensely attracted to these ideas, and sought a way to adapt them to the compositional process. The result was the Third Piano Sonata, a work-in-progress that to this day awaits “completion.”

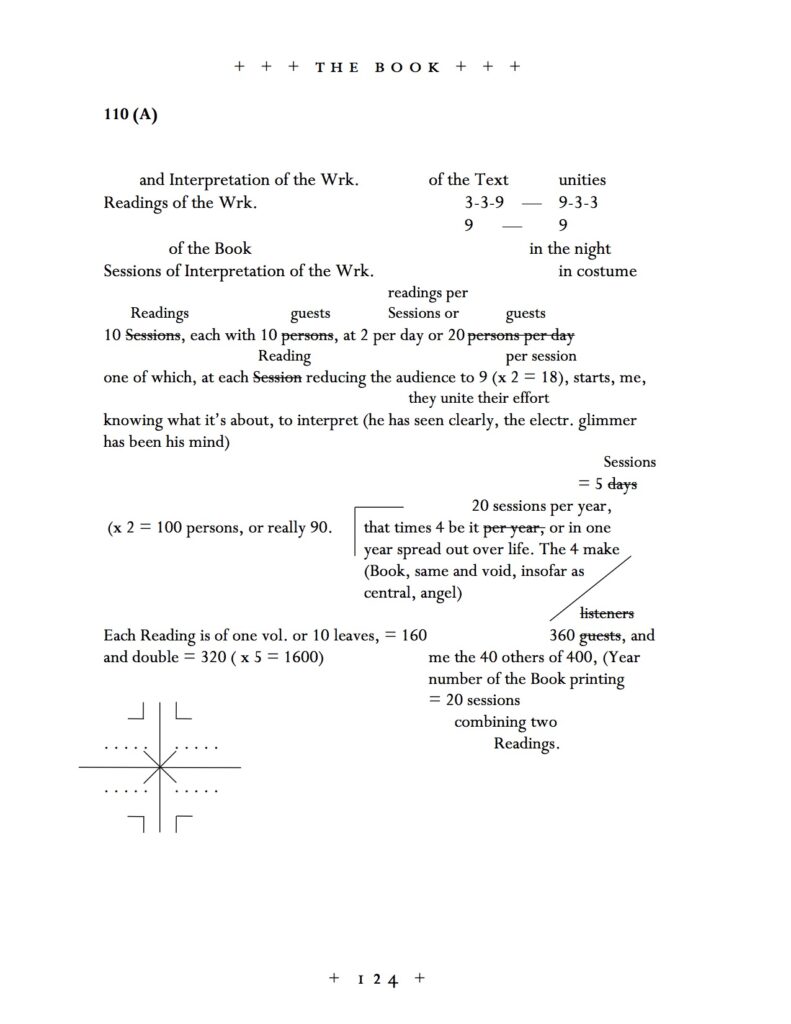

Page from Gorelick’s translation of Mallarmé’s Livre (Credit: Hyperallergic)

Page from Gorelick’s translation of Mallarmé’s Livre (Credit: Hyperallergic)

Design

The ideal version of the Third Piano Sonata has five movements, which Boulez called formants. The central movement—formant 3—must be either Constellation or Constellation-miroir. The remaining four formants are grouped into pairs: Antiphonie/Trope, and Strophe/Séquence. The pianist selects which pairs are placed before and after formant 3.

Only formants 2 and 3 were published in Boulez’s lifetime, so the work has never received a complete public performance by anyone save Boulez himself.

Formant 2—Trope

Trope is made up of four fragments, each taking its name from related terms of literary criticism: Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire, and Glose. The performer is free to choose which fragment serves as the beginning; as long as Commentaire is played either before or after Glose, and the performer plays through each fragment to the end in the direction selected.

According to Robert Nemecke:

The four section delineate various relationships between principal notes and their tropes. In Texte, the relationship is monodic; in Glose, it is exclusionary, at least with respect to the main note; in Parenthèse, the musical flow is interrupted regularly by intermittent insertions; while in Commentaire, the most complicated trope, the assembled techniques are recapitulated.

Overall a pianist is presented with eight different ways of navigating the Trope cycle. A clear inspiration here is Finnegans Wake; in fact, Boulez indicates that the score for Trope should be bound in a spiral to emphasis its nonlinearity.

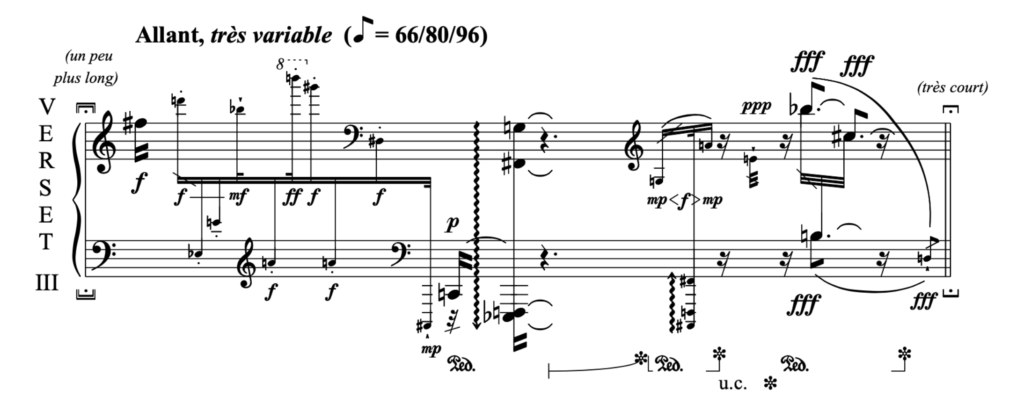

Formant 3—Constellation/Constellation/miroir

The next formant, Constellation, serves as a labyrinth of sorts, allowing the performer the freedom to select a path through the movement from several alternative possibilities. (Something like an old “Choose Your Own Adventure” book.) The movement is essentially comprised of a series of “vertical” fragments called points which are printed in green ink; and “horizontal” fragments called blocs, which are printed in red ink. (Although a small sub-section named Mélanges reverses these color assignments.) As their names suggest, points are composed of single notes, and blocs consist of chords and arpeggios. After playing a fragment, arrows in the score prompt the performer to go to one of four possible next fragments, and so on through the piece. As if this weren’t enough, the opposite sides of the sheets contain Constellation-miroir, a reversed form of Constellation which may be played in its stead. (Interestingly, only Constellation-miroir has been formally published.)

Formant 3 makes unusual demands on the performer apart from the need to make choices regarding organization and rhythm. As the pianist Steffen Schleiermacher points out, the performer must also employ various resonance effects, including near-virtuoso “legwork” on the pedal and the use of piano harmonics. One key is depressed in a way that makes no sound, but causes a resonance effect when a neighboring key is firmly struck: “The sounds seem to cast virtual shadows, to continue to sound in the background, while the next structure appears in the foreground.” (Schleiermacher, 2000)

“Sigle” and Antiphonie

In 1968 Boulez published a new fragment called “Sigle.” (The name should spark the interest of a Finnegans Wake reader, who may be reminded of Joyce’s “Sigla.”) It was first recorded by Steffen Schleiermacher in 2000, who placed it between Trope and Constellation-miroir. In 2007 Boulez allowed formant 1 to be played in private workshops, and “Sigle” became attached to Antiphonie. Intrigued by the renewed interest in the Third Sonata from modern musicians and musicologists, Boulez agreed to finally complete Antiphonie, but his death in 2016 left only a series of extraits: “Antiphonie I,” “Antiphonie II,” “Sigle,” and “TRAIT INITIAL / premier trait médian.” As explained by Boulez’s publisher, Universal Edition:

Against all expectation, it was on the initiative of Universal Edition, on the occasion of a working meeting at the Paul Sacher Foundation on the 13th September 2007, exactly half a century after the first performance of the Third Sonata in its original form, that the composer finally allowed himself to be persuaded to look once again at these scattered fragments, with a view to a possible completion of the movement—a project he was unfortunately unable to carry out on account of the deterioration in his health, which finally carried him off on the 5th January 2016 at Baden-Baden. In spite of this ultimate obstacle, the publishers urged Krystyna Reeder, the copyist who had worked with the composer up to the eve of his death, to complete the project as far as was possible—a plan frustrated in its turn by her own sudden death in Paris on the 3rd January 2018, indicating what some might interpret as a certain curse attached to this work!

Despite this series of unfortunate events, UE published the fragments in 2019. Three years later, Florent Boffard recorded the first commercial version of the Third Piano Sonata to include a realization of Antiphonie. As Robert Piencikowski, the former curator of the Pierre Boulez Collection at the Paul Sacher Foundation, writes in his liner notes to the Boffard disc:

Here then is its first, posthumous recording, at last giving us a glimpse of what the sonata would have become had the composer been able to finish it. The listener will notice the transformation of the piano writing of the first Trait (1963)—a transition between Chapter II of the Second Book of Structures for two pianos (1961) and the initial cadenza of Éclat (1965).

Music is a labyrinth with no beginning and no end, full of new paths to discover, where mystery remains eternal.

—Pierre Boulez

Perception

So how does all this actually sound? Oddly enough, although relentlessly atonal, Trope and Constellation are fairly gentle, if a bit prickly. Both formants are basically static, lacking any sense of motion or narrative development, and in both, silence plays an important role. The music takes the form of tiny, spiky clusters of notes, each embedded in a field of silence with varying degrees of lingering sustain or pointillist crispness connecting them to the next cluster. Like sporadic drops of icy rain falling into a clear pool of silence, the music evades any sense of dramatic continuity, forcing the listener to focus on each isolated event rather than its overall relation to the whole. Although each cluster has its own microcosmic sense of dramatic unity, the sequence of clusters is without any perceivable structure or theme. Indeed, a casual listener remains blissfully unaware of the underlying mechanisms needed to generate the music, and I must confess, that having heard countless recordings of the score, I could not readily tell that I was listening to different permutations. Like Finnegans Wake, the overall piece retains its core identity no matter where you dip in for sampling.

Choice, Chance, and Chaos

Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata was not without its share of controversy. Although Boulez readily credits Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance) as an influence, the piece bears even more similarities to Mallarmé’s notes on his unrealized project Livre, in which the poet describes a book with interchangeable pages that may be read in any order. Mallarmé indicates that such a work could be read by various “operators” to different audiences, all of which would generate unique experiences and interpretations. Moreover, Mallarmé used terms like “Constellations” to describe the indeterminate aspects of his idealized open work. Boulez, however, maintains that he developed his ideas independently of Livre, and that he only became aware of its existence after he had composed the majority of his sonata.

The piece also contributed to the growing antipathy between Pierre Boulez and John Cage after their falling out. In 1957 Boulez published an essay called “Aléa” (meaning a single die) in which he detailed his ideas on “controlled chance,” or limited indeterminacy; a compositional technique that would open a work to indeterminacy while still preserving creative control. In this essay he attacked pure chance operations, and rather arrogantly implied that those who pursued such a course were foolish and incompetent. The attack was obviously directed at Cage, who became quite angry with Boulez, once a friend and creative associate. Cage remarked, “After having repeatedly claimed that one could not do what I set out to do, Boulez discovered the Mallarmé Livre…. With me the principle had to be rejected outright, with Mallarmé it suddenly became acceptable to him. Now Boulez was promoting chance, only it had to be his kind of chance.” Cage’s anger was compounded by the popularity of the essay, which firmly established Boulez’s term “aleatory music” as the label for the type of music that Cage had practically invented.

The work is also controversial in the broader context of Modernist music, specifically as realized by Boulez in his three piano sonatas, which are often criticized as being overly academic or even “unlistenable.” Many critics have remarked upon the apparent disconnect between the underlying theory and the music itself. While the process behind the Third Piano Sonata is ingenious, and the sheet music has a visual appeal that cannot be denied, some listeners find the music unpleasant, lacking the elegance and artistry of the printed score. As composer and critic Peggy Glanville-Hicks of the New York Herald Tribune wrote about the Second Piano Sonata, “The Boulez Sonata—to this reviewer—is chaos, organized, stabilized chaos….To the eye and intellect, the printed page of Boulez presents logic and design, but to the ear, its true arbiter, these are not apparent.”

While Glanville-Hicks makes a valid point, she ironically underlines the appeal of Boulez for some listeners: “organized, stabilized chaos.” Not everyone’s ear conducts the same arbitration, and Boulez is the perfect example of the humorous caveat, “You’ll like it if you’re the type who likes that sort of thing.” When played with sensitivity and conviction, Boulez’s piano sonatas reveal a sparkling world of abstract beauty and turbulent passion. Whether or not one finds them to one’s taste, they’re important works of twentieth-century music, and should not be overlooked.

Excerpts from To Boulez and Beyond

By Joan Peyser

To Boulez and Beyond: Music in Europe Since the Rite of Spring

Billboard Books, 1999

In the fall of 1943, when Boulez first arrived from Provence, he moved into a tiny apartment on rue Beautreillis, near the historic Place des Vosges. In his cluttered, tiny rooms he kept his manuscripts rolled up like papyrus on the floor. In addition to the manuscripts there was a narrow bed, a small desk, an electric heater, and several African masks. Reproductions of Paul Klee were on the walls; the works of Rimbaud, Mallarmé, and James Joyce were on the shelves. (Chapter 19)

Perhaps to resist the increasing popularization and, on occasion, the vulgarization of art which had flourished under neoclassicism and socialist realism and had been encouraged by radio and films, perhaps to restore a more intellectually aristocratic elite, many artists—both in Europe and the United States—began to build on the refined, inaccessible language that had roots earlier in the century. This is not to say that it was the intent of Schoenberg, Kandinsky, or Pound to be as hermetic as they were; it is rather to point out that inaccessibility was certainly a consequence of what each of them did. But those artists who came of age after World War II elevated this secondary consequence to a primary purpose. For Boulez, James Joyce was a critical symbol. He had read Ulysses in French, and an exhibit in 1949 at Le Hune bookshop in Paris increased his excitement about Joyce’s work. Recalling what drew him to Joyce, Boulez cites the “specificity of technique for each chapter, the fact that technique and story were one. The technique reflected exactly what Joyce meant; it was rich and I had never met it before in a book.”

But it was Finnegans Wake that overwhelmed the group. In a letter to Cage written in December 1949, a young French poet wrote:

The advent of Finnegans Wake at Pierre’s has not yet finished provoking many arguments and discussions. There were several stormy sessions on Rue Beatreillis where the tone of things reached such a high pitch that the vocabulary consisted of several forceful “merdes” which each of the participants flung at each other without any mental reservation concerning the parsimony of the words used.

If by now the heated arguments have abated somewhat, discussions are still frequent on the subject. I must admit, to be completely objective, that after experiencing Joyce in a very serious way my admiration for Faulkner has vanished.

It is possible that technique alone did not draw Boulez to Joyce for the similarities between the two artists transcended technique. Both Boulez and Joyce were raised devout Catholics; both became disenchanted when they were still young. Both were clearly in search of a father, a search that dominated both men’s lives. (Leopold Bloom was to Stephen Dedalus what Barrault, Souvchinsky, and Strobel were to Boulez.) Both moved towards revolution in the political arena but neither liked manifestos when drawn up by others. Art alone was the route for Joyce and Boulez. It gave them the stature and dignity they sought. Able to renounce the dogma they had been taught, each cast his own revolution in most dogmatic of aesthetic terms. Thus Boulez built Structures on a medieval-like musical language with its secrets hidden from the public at large. Like Finnegans Wake, which inspired numerous “skeleton keys” and “guides,” Structures inspired musical analyses. That the traditional value of beauty played virtually no role in Boulez’s conception is revealed by a passage Boulez wrote to Cage on the eve of his trip to New York: “Soon Monroe Street will see us and hear us. Tell [the pianist] David Tudor, whom I am very eager to know, that he should get some aspirin ready—I am doing as much myself—for Structures is not easy to listen to. But since he has worked on your Music for Changes [here Boulez makes a diagram excerpting CAGE from CHANGES] I would say he is properly prepared.” (Chapter 24)

Excerpts from ‘Sonata, que me veux-tu’

By Pierre Boulez

Orientations

Harvard University Press, 1986

Originally published in Darmstädter Beiträge zur neuen Musik, Vol. III, 1960, pp.27-50.

Why compose works that have to be re-created every time they are performed? Because definitive, once-and-for-all developments seem no longer appropriate to musical thought as it is today, or to the actual state that we have reached in the evolution of musical technique, which is increasingly concerned with the investigation of a relative world, a permanent ‘discovering’ rather like the state of ‘permanent revolution’. […]

What impelled me to write this Third Piano Sonata? It may well be that literary affiliations played a more important part than purely musical considerations. In fact my present mode of thought derives from my reflections on literature rather than on music. Not that I had any wish to write music with a literary reference, for in that case the literary influence would have been very superficial. No, the fact is that I believe that some writers at the present time have gone much further than composers in the organization, the actual mental structure, of their works.

I must at once disclaim any idea of embarking on a literary dissertation, something for which I have no qualifications. I simply want to say something about the two writers who have the most stimulated my thinking and thus most profoundly influenced me, namely Joyce and Mallarmé. A close examination of the structure of Joyce’s two great novels [Ulysses and Finnegans Wake] will reveal the astonishing degree to which the novel has been revolutionized. The novel observes itself qua novel, as it were, reflects on itself and is aware that it is a novel—hence the logic and coherence of the writer’s prodigious technique, perpetually on the alert and generating universes that themselves expand. In the same way music, as I see it, is not exclusively concerned with ‘expression’, but must also be aware of itself and become the object of its own reflection. For me this is one of the primary essentials of the language of poetry, and has been since Mallarmé, with whom poetry became on object in itself, justified in the first place by poetic research, in the true sense.

In music the difficulty of taking this step is a matter of style. Music has no ‘meaning’: it does not make use of sounds which hover ambiguously, as words do, between objective sense and reflective significance. In principle both poet and novelist express themselves by means of words taken from the current vocabulary, and can make use of the ambiguity arising from the fact that a word can both denote a utilitarian object and also serve as a cipher of reflective thought. A large part of Joyce’s world is constructed from the conscious and rational application of ‘stylistic exercises’ of this kind. Everyone will remember Stephen’s excursus on Hamlet in chapter 4 of Ulysses and that astonishing chapter 14, where the growth of a foetus in the womb is suggested by a series of pastiches in which the evolution of the English language is traced from Chaucer to the present day.

Words can be used in this way because they possess a power of reference, a ‘meaning’. With music the problem is different and, as we shall see, it presents itself in a different guise: here the only ‘play’ possible is an interplay between styles and forms…. It must be our concern in the future to follow the examples of Joyce and Mallarmé and to jettison the concept of a work as a simple journey starting with a departure and ending with an arrival. We are assured by Euclidean geometry that a straight line is the shortest way from one point to another, which is roughly the definition for a closed cycle. In this perspective a work is one, a single object of contemplation or delectation, which the listener finds in front of him and in relation to which he takes up his position. Such a work follows a single course, which can be reproduced identically and is unavoidably linked to such considerations as the speed at which it unfolds and the immediacy of its effectiveness. Finally, Western classical music is opposed to all active participation, and this sometimes makes it difficult to establish any really significant contact, even if actual boredom does not intervene between the musical object and the listener contemplating it. […]

As against this classical procedure the idea of a maze seems to me the most important recent innovation in the creative sphere. I can already hear the malicious retort that I shall inevitably receive—that quite a number of Ariadne’s clue-threads may well be needed to make any progress in such a maze possible, and that not everyone feels the call to become a Theseus. Don’t let this worry us! The modern conception of the maze in a work of art is certainly one of the most considerable advances in Western thought, and is one upon which it is impossible to go back…. As I see it, the idea of a labyrinth, or maze, in a work of art is roughly comparable to Kafka’s procedure in his short story ‘The Burrow’. The artist creates his own maze; he may even settle in an already existing maze since any construction he inhabits he cannot help but mould to himself. He builds it in exactly the same way as a subterranean animal builds the burrow so well described by Kafka, continually moving his supplies for the sake of secrecy and changing the network of passages to confuse the outsider. Similarly the work must keep a certain number of passageways open by means of precise dispositions in which chance represents the ‘points’, which can be switched at the last moment. It has already been brought to my notice that this idea of ‘points’ does not really belong to the category of pure chance but rather to that of indeterminate choice, which is something quite different. In any construction containing as many ramifications as a modern work of art total indeterminacy is not possible, since it contradicts—to the point of absurdity—the very idea of mental organization and of style. Given these facts, the very physical appearance of the work will be changed; and once the musical conception has been revolutionized, the actual physical presentation of the score must inevitably be altered.

Here again I should like to refer to my own personal experience. Reading and rereading Mallarmé’s ‘Le Coup de dés’, I was greatly struck by its appearance on the page, its actual typological presentation, and came to realize that this formed an essential part of the new form: the typographical material had to undergo a metamorphosis for Mallarmé. The actual printing of ‘Le Coup de dés’ is of fundamental and primary importance, not only as regards pagination—the spatial disposition of the text with its blanks—but also the typographical character. […]

Such formal, visual, physical—and indeed decorative presentation of a poem (though the poet does not include this)—suggested to me the idea of finding equivalents in music. […]

My sonata, with the five formants that it comprises, may be called a kind of ‘work in progress’, to echo Joyce. I find the concept of works as independent fragments increasingly alien, and I have a marked preference for large structural groups centered on a cluster of determinate possibilities (Joyce’s influence again). The five formants clearly permit the genesis of other distinct entities, complete in themselves but structurally connected with the original formants: these entities I call développants. Such a ‘book’ would thus constitute a maze, a spiral in time. […]

One final word. Form is becoming autonomous and tending towards an absolute character hitherto unknown; purely personal accident is now rejected as intrusion. The great works of which I have been speaking—those of Mallarmé and Joyce—are the data for a new age in which texts are becoming, as it were, ‘anonymous’, ‘speaking for themselves without any author’s voice’. If I had to name the motive underlying the work that I have been trying to describe, it would be the search for an ‘anonymity’ of this kind.

—Pierre Boulez, 1960. Translation by David Noakes and Paul Jacobs.

Liner Notes (Music & Arts 1993)

By Jeffrey Swann

Charles Wuorinen: Second Sonata; Pierre Boulez: Troisième Sonate pour Piano

Music & Arts, 1993

The Troisième Sonate pour Piano of Pierre Boulez is one of history’s most celebrated incomplete works. Indeed, it is practically unique in that the composer himself retired considerable portions of the work after its initial appearance in 1958 “for revision”—and 35 years later has still not reinstated them. It is probably safe to say that the two movements—or formants as Boulez calls them—that we now have represent the definitive form of the work. It is nevertheless worth while to give the initial conception which is as follows:

A. Antiphonie

B. Trope

C. Constellation or Constellation-miroir

D. Strophe

E. Séquence

From what remains of the original form, we can see that Antiphonie and Séquence were very brief, whereas Strophe was approximately of the size of Trope; the two formants we have, therefore, represent by far the greater part of the work. The second part of the title Constellation, Constellation-miroir, refers to the fact that this formant may be played in reverse order—i.e., in a mirror image—if Trope is to follow it instead of preceding it.

The Troisième Sonate is a remarkable mid-20th-century expression of a peculiarly French sound universe. One feels everywhere not so much the influence but the shadow of Debussy and Messiaen in its bright colors and splashy effects. Nevertheless the salient quality of the Troisième Sonate is its aleatoric aspect—that at least in theory each performance should be quite different in content, and that the performer should have the power to make significant compositional decisions, ideally spontaneously. In 1958 this seemed to represent a total change in direction of Boulez’ compositional style. It was an attempt to express the aesthetic of the open work; the conception of a work which is not exhausted in any given performance but which constantly redefines itself within precise parameters given by the composer, the concept of the “work in progress.” The expression “work in progress” links the Troisième Sonate to James Joyce’s original title for Finnegans Wake. This connection and similar connections to other literary works, especially Mallarmé, is particularly important, especially in Boulez own explanation of the work’s aesthetic.

It must be said that from the historical reference of 1993, the highly pretentious and complex terminology and defining aesthetic dialectic in which Boulez and his commentators luxuriated seems as arcane and indeed of as distant a past as early 18th-century writing about the Colors and Temperaments of music—or even a treatise by Boetheus in the early Middle Ages. From our standpoint, the introduction of chance elements seems more a response to the influence of John Cage and other American innovators of the early 50s, as well as a necessary and highly salubrious reaction to the totally organized music of the Darmstadt School, the climax of which is manifested in Boulez Structures, especially the Second Book. The chance elements here are far less pervasive than in Cage but nevertheless give the present work a fluidity and spontaneity which is a new and endearing quality of this work as well as works such as the Mallarmé Livre and Domaine.

The very idea of recording a piece which should be compositionally different in each performance is, of course, contradictory. I have attempted to mitigate this contradiction by giving two versions of each formant. Neither of these should be seen as definitive in any way, but rather representational of the work’s kaleidoscopic possibilities.

The organization of Trope is relatively simple. The formant consists of four sections, Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire, and Glose. These may be played in various orders (actually there are eight possible sequences). The dramatic effect of the formant varies radically according to the order chosen—the order usually performed, Texte, Parenthèse, Glose, Commentaire, proceeds from simplicity to ever-growing complexity and brilliance and concludes emphatically. This is the order I have chosen for one of my performances. Other orders, however, offer quite different and fascinating perspectives, as my alternative solution: Commentaire, Glose, Texte, Parenthèse, shows.

Other than the sequence of sections, the aleatoric aspect of Trope is represented in passages in the sections Parenthèse and Commentaire, which are written in smaller notation and whose performance is optional. If performed, these passages are to be played in a markedly freer style than the others. I might add that this is extremely difficult to portray in performance, since the rhythmic complexity of the work as a whole makes rubato a problematic concept in practice. Nevertheless the inclusion or omission of various passages greatly alters the dramatic quality of the sections involved.

The third formant, Constellation or Constellation-miroir, is much more complex in its aleatoric possibilities. In this formant the performer is given a large number of short fragments varying in length from one or two to perhaps as many as 30 seconds. Each fragment is preceded and followed by a series of arrows in myriad and highly mysterious forms whose purpose is to indicate from which fragments it is possible to arrive at the present one and to which fragments it is possible to go. Only the initial fragment, which lacks preceding arrows, and the concluding one, which lacks following arrows, differ. One must play all fragments in any given performance and no fragment may be repeated. This limitation severely restricts the possibilities of fragment order. Nevertheless there must be many thousands of potential performance possibilities. In addition, other characteristics, such as dynamics and tempo, vary according to the route by which one has arrived at a given fragment.

The fragments themselves are printed in either red or green and belong to compositional groups entitled Blocs or Points. The formant opens (or closes in its Miroir version) with a short section entitled Mélange in which Blocs and Points are intermingled. The Blocs and Points sections have quite noticeably different textures and moods. The Points are distinctly polyphonic and linear and greatly exploit a peculiar technique by which the pianist creates a shifting kaleidoscope of overtones by pressing down and releasing individual notes and chords without letting them sound. In many places this technique represents the most difficult aspect of the work to realize, especially on pianos without a lot of resonance. The Blocs sections are much more chordal and utilize dense blocks of notes which are held down over extended passages without being played, creating a distinctly “blurry” sound effect.

Given the complexity of this formant, it is obviously a great temptation for the performer to decide in advance which route he will take. Indeed, the danger of finding oneself in a “dead end” from which one is forced either to skip a passage or repeat one is so great that a certain amount of preplanning is probably essential. Nevertheless it is important to retain the spontaneous quality of the work. As can be seen from the two performances on this disc, the possibilities for variety are enormous. I myself arbitrarily decided in the first performance to take those paths which seemed to offer the greatest possibilities for continuity, both dramatic and sonorous, while in the second performance to take those which offered the greatest possibilities for abrupt contrast.

Liner Notes (Mirare 2022)

By Robert Piencikowski

Florent Boffard: Beethoven, Berg, Boulez

Mirare, 2022

An ambitious project to transpose Mallarmé’s Livre into musical terms, which underwent a long process of revision and polishing before being abandoned for larger projects, the Third Piano Sonata marks Boulez’s contribution to the experimentation with formal relativity that crystallised in the mid-1950s. He was stimulated by the example of his fellow composers (John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henri Pousseur) to devise a suspended form appropriate to the suspension of tonal functions that lay at the origins of dodecaphony, in the form in which it began to be disseminated in France in the aftermath of the Second World War. Since he envisaged serialism in a post-Debussyan perspective, he had to free Schoenberg’s technique from the influence of Brahms, in order to put in its place a polyrhythmic agogics derived from Stravinskian technique. The path lay open for an expansion of the opposition between strict and free writing, with the option of which itinerary to follow left to the free choice of the performer. With bithematicism replaced by the opposition between static and dynamic textures, each formant offered the performer a specific outline within the general trajectory: a form conceived as a spiral (Trope), a fan (Constellation-Miroir) or folding panels (Antiphonie). While still in its provisional state, the sonata was premiered in Darmstadt and West Berlin in September 1957, at the height of the Cold War, in the midst of debates over the freedom of culture, following the aesthetic imperatives of Socialist Realism imposed on creative artists in the countries of the Communist bloc. In short, such debates were between countries free or not to practise so-called ‘contemporary’ art, considered as asocial because it was unintelligible to the working masses—and thus an unfortunate resurgence of the ‘degenerate art’ of the inter-war period. Tonality or atonality, figuration or abstraction: one can imagine the dismay of the partisans of one camp or the other when Stravinsky, then held to be the unshakeable bastion against Viennese twelve-note composition, suddenly rallied to the cause of the young composers who had just succeeded in fusing two tendencies hitherto deemed incompatible.

In the face of the increasingly wide intervals between his successive revisions, and the difficulties encountered in the process of publication (page layout, binding), Boulez finally gave up the idea of completing the sonata, leaving the unfinished fragments in cardboard boxes in his archives. After exceptionally authorising partial performance of Antiphonie in the context of workshop-concerts, he was finally persuaded by his publisher to complete the unfinished segments—a last endeavour interrupted by his death. Here then is its first, posthumous recording, at last giving us a glimpse of what the sonata would have become had the composer been able to finish it. The listener will notice the transformation of the piano writing of the first Trait (1963)—a transition between Chapter II of the Second Book of Structures for two pianos (1961) and the initial cadenza of Éclat (1965).

Recordings

Once considered an exotic bête noire of Modernism, Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata received a surge of interest around the turn of the millennium. There’s been an abundance of new recordings over the last twenty years, and the sonata is increasingly played in concerts all over the world—including the United States, a bastion of inflexible, blue-haired classicism. More and more younger pianists see Boulez’s sonatas as vital additions to the twentieth-century repertory, like Ligeti’s Études or Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke. The following section details eighteen commercially available recordings of the Third Piano Sonata, listed in order of performance date.

Recommendations

For visitors who’d just like a quick recommendation, my favorite recording of the Third Piano Sonata is the 1993 Music & Arts CD by Jeffrey Swan, which offers two variations of Trope. It’s also accompanied by Wuorinen’s under-appreciated Second Sonata. The 1995 Naxos set by Idil Biret is another excellent choice, particularly for listeners seeking a more expressionistic interpretation of Boulez. As for more recent performances, the 2022 Florent Boffard recording for Mirare is essential. Not only does Boffard play the Third with brilliance and grace, it’s the only recording to include formant 1, Antiphonie.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1959)

Piano: Pierre Boulez

CD: Darmstadt Aural Documents, Box 4: Pianists. Neos 11630 (2016)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

On 30 August 1959 Boulez gave a recital of the Third Piano Sonata at Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt. That recording is available as part of Neos’s staggering “Darmstadt Aural Documents” series, a 21-CD compilation spread across four box sets. The Third Piano Sonata is located in Box 4, Disc 2, “Piano Repertoire of the 1950s/1960s.” The 20-minute long track is not available as an individual download, but if you have $70 laying around, the entire box is worth a listen—a very long, thorny, drive-everyone-from-your-house listen! Fortunately, the ever-dependable Naxos has placed the entire box set on YouTube.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1968)

Piano: Claude Helffer

LP: Webern, Boulez, Berio. Guilde Internationale du Disque SMS 2590 (1968)

Purchase: LP [eBay]

It’s surprisingly difficult to establish the first commercial recording of Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata. So far the leading contender is this Guilde Internationale LP featuring the dashing French pianist and former Résistance fighter Claude Helffer (1922–2004). The album itself does not feature a copyright date; but an extensive Internet search reveals 1968 as the most probable year of production. (A few sources say 1960, but that’s contradicted by Helffer’s liner notes.) Helffer plays Constellation-miroir first, followed by Trope in this order: Glose, Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire. The LP also features Boulez’s First Piano Sonata, Berio’s Sequenza IV, and two pieces by Webern.

|

|

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1973)

Piano: Charles Rosen

LP: Piano Sonata No. 1; Piano Sonata No. 3: Trope, Constellation. Columbia Masterworks M 32161 (1973)

Digital: Piano Sonata No. 1; Piano Sonata No. 3: Trope, Constellation. Sony G010003220429S (2014)

CD Box Set: Charles Rosen Plays Modern Piano Music. Sony 88985373772 (2017)

Purchase Album: Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Purchase Box Set: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

For the Third Piano Sonata’s debut on Columbia, New York pianist Charles Rosen played Trope followed by Constellation-miroir. In 2014 Sony digitized the 41-year old recording and made it available for downloading and streaming. Unfortunately, most sources mislabel formant 3 as Constellation rather than Constellation-miroir. This mistake was repeated in the 2017 box set, Charles Rosen Plays Modern Piano Music. No matter—the budget-priced box set is worth the purchase, and contains Boulez’s First Piano Sonata as well as excellent performances of Stravinsky, Webern, and Carter.

|

|

Boulez: Trope from Third Piano Sonata (1976)

Piano: Klára Köremendi

LP: Oeuvres Contemporaines pour le Piano. Hungaroton SLPX 11771 (1976)

CD: Klára Köremendi Piano Recital. Hungaroton HCD 31606 (1995)

Purchase: Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Klára Köremendi is a Hungarian pianist known for her interpretations of French composers such as Ravel, Debussy, and Satie. She also embraced modern composers, and recorded an LP of “Contemporary Works for the Piano” for Hungaroton in 1976, complete with requisite seventies cover. The album contains the entirety of Boulez’s First Piano Sonata, but only Trope from the Third, which she plays as Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire, Glose. In 1995 Hungaroton reissued the album on CD as Klára Köremendi Piano Recital, expanding the set with two pieces by Attila Bobay and József Soproni.

|

|

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1981)

Piano: Claude Helffer

LP: Pierre Boulez: Trois Sonates pour Piano. Astrée AS 60 (1981)

CD: Pierre Boulez: Trois Sonates pour Piano. Astrée Auvidis E 7716 (1986)

Reissue CD: Pierre Boulez: Trois Sonates pour Piano. Montaigne, MO 782120 (2000)

Purchase: LP [Amazon], CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

In July 1980, Claude Helffer recorded all three of Boulez’s piano sonatas in the Théâtre Municipal de Vevey. The set was released on LP by Astrée as Pierre Boulez: Trois Sonates pour Piano. Like Helffer’s earlier recording for Guilde Internationale, the cover sported an image of the green points and red blocs of Constellation. Five years later the album was issued as a compact disc, then reissued in 2000 by Montaigne with a much blander cover. As with his 1968 recording Helffer begins with Constellation-miroir, but here Tropes follows the order Textes, Paranthèse, Glose, Commentaire.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1985)

Piano: Herbert Henck

LP: Pierre Boulez: Première Sonate, Deuxième Sonate, Troisième Sonate. Wergo WER 60120/21 (1985)

CD: Pierre Boulez: Première Sonate, Deuxième Sonate, Troisième Sonate. Wergo WER 60121-50 (1985)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube

The German pianist Herbert Henck has built a reputation performing difficult pieces of contemporary music by the likes of Stockhausen, Barraqué, and Nancarrow. This 1985 album collects all three of Boulez’s sonatas. Henck’s playing is dramatic and commanding, but his performance of the Third Piano Sonata is somewhat idiosyncratic, leaning heavily on the reverb so beloved by Eighties recording engineers. As critic Fabrice Fitch smartly remarked in Gramophone, “Henck’s clinical emphasis on the belly of the instrument is crucial in the Constellation-miroir movement of the Third: the recording hones in on the pedal resonances to a degree unparalleled in the other discs. (Henck really stretches out the pauses and resonances, too, and to be fair, some may find his emphases, and those of his sound engineer, exaggerated.)”

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata [2 Versions] (1993)

Piano: Jeffrey Swann

CD: Charles Wuorinen: Second Sonata; Pierre Boulez: Troisième Sonate pour Piano. Music & Arts CD-763 (1993)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

Released in 1993 by the Texan pianist Jeffrey Swann, this disc contains two versions of Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata accompanied by Charles Wuorinen’s wonderful Second Sonata. Swann’s playing throughout the disc is superb, sensitive to nuance and attentive to the changing dynamics of each piece. He offers two different versions of the Third, varying the order of Trope and taking different paths through Constellation-miroir. Swann’s liner notes are extremely informative, and it’s obvious his commitment to the work is total. Highly recommended. (Plus—bonus Kandinsky!)

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (1995)

Piano: Idil Biret

CD: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1–3. Naxos 8.553353 (1995)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Naxos | YouTube [Part 1 | Part 2]

When critics discuss their favorite recordings of Boulez’s piano sonatas, this recording by the Turkish pianist Idil Biret is frequently found near the top of the list. A renown interpreter of Chopin, Biret’s exquisite playing is subtle and wonderfully emotive, firmly locating Boulez’s sonatas in a long line of French expressionism. She plays Trope as Glose, Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire followed by Constellation-miroir. Highly recommended.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2000)

Piano: Steffen Schleiermacher

CD: Piano Music of the Darmstadt School, Vol. 1. MDG Scene MDG 613 1004-2 (2000)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon]

Online: YouTube [“Sigle” from formant 1, Antiphonie]

The German pianist Steffen Schleiermacher is a passionate advocate of contemporary music, and has recorded artists ranging from Arnold Schönberg to Philip Glass. (He also has the complete piano music of John Cage to his credit.) Here Schleiermacher attacks Boulez’s Third with clarity and precision. He outlines Boulez’s hard-edged modernism better than Biret or Chen, a “Darmstadt” interpretation that lowers the temperature of their near-Romantic “Francophone” readings. Schleiermacher plays Trope as Glose, Commentaire, Texte, Parenthèses followed by Constellation-miroir. This disc was also the first commercial recording to include “Sigle,” which Schleiermacher places between Trope and Constellation-miroir.

|

|

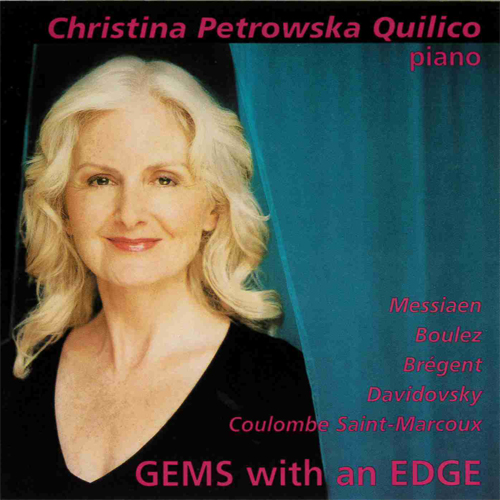

Boulez: Trope, from Third Piano Sonata (2003)

Piano: Christina Petrowska Quilico

CD: Gems with an Edge. Welspringe WEL0007 (2003)

CD: Sound Visionaries. Navona NV6358 (2021)

Purchase: CD (Gems) [CMC], Digital (Visionaries) [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Trope]

The Canadian pianist Christina Petrowska Quilico has recorded several knotty pieces of modern music over the course of her long career, the natural outcome of one who studied in Darmstadt with Stockhausen and Ligeti. Her interpretation of Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata was realized while working with the Maestro himself—her YouTube video of Trope features images of the score marked by her copious notes and charming illustrations.

The first album to collect Quilico’s “modern” pieces was produced by CBC-Radio Canada in 2003. Called Gems with an Edge, the disc features selections from Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’Enfant Jésus, Brégent’s Geste, Davidovsky’s Synchronisms VI, Saint-Marcoux’s Assemblages, and Trope from Boulez’s Troisième Sonate. (The disc also contains liner notes for the sonata penned by yours truly.) Nearly 20 years later, her recordings of Vingt regard and Trope were reissued by Navona Records on Sound Visionaries, now joined by Boulez’s First Piano Sonata and selections from Debussy’s Preludes Book 2. Although Quilico only plays formant 2, it’s eight minutes of pure magic. In my above essay I remarked, “When played with sensitivity and conviction, Boulez’s piano sonatas reveal a sparkling world of abstract beauty and turbulent passion.” It was Quilico’s recording I had in mind when writing that sentence!

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2005)

Piano: Pi-Hsien Chen

CD: Notations & Piano Sonatas. Hat[now]ART 162 (2005)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Part 1 | Part 2]

Another excellent set of Boulez sonatas, this disc also includes Douze Notations pour Piano from 1945. The pieces are played by the Taiwanese pianist Pi-Hsien Chen, a renown interpreter of Bach whose interest in modern music embraces Messiaen, Stockhausen, and Boulez. (Chen was famously plagiarized in the bizarre “Joyce Hatto hoax.”) Like Biret, Chen’s playing is decidedly expressionistic, and may even please listeners unaccustomed to atonal music! She plays Trope as Texte, Parenthèse, Commentaire, Glose followed by Constellation-miroir.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2005)

Piano: Paavali Jumppanen

CD: Boulez: The Three Piano Sonatas. Deutsche Grammophon 00289 477 5328 (2005)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

This fourth disc of Boulez sonatas are performed by the Finnish pianist Paavali Jumppanen, who organizes the Third as Parenthèse, Glose, Commentaire, Texte followed by Constellation. It’s the first album to include Constellation rather than Constellation-miroir—a sign of Boulez’s post-millennial change of heart regarding recordings of unpublished formants. Jumppanen plays the Third with an intuitive sense of discovery, and his interpretations of the “labyrinth” have been praised by Boulez himself. Recommended.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2011)

Piano: Håkon Austbø

CD: Wanted: Boulez, Carter & Schaathun. Aurora ACD5071 (2011)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

Håkon Austbø is a Norwegian pianist with several highly-regarded contemporary recordings to his credit. As far as I know, he does not have a reputation as a badass, has never previously been photographed wearing a muscle shirt and cowboy hat, and has not committed any crimes worthy of earning a “wanted” poster. That makes this the most puzzling album cover among this bunch—what’s with the “bad boy” vibes? An homage to Boulez’s reputation as an enfant terrible? A weird display of affection for Merle Haggard? While the cover might lead one to expect a honky-tonk rendition of the Third—which, to be fair, would be amazing—Austbø shows the same masterful attention to detail he brought to his 1994 recording of Messiaen’s Vingt regard. This is particularly evident in the spaces between notes, where he extracts just the right degree of resonance or silence. Austbø plays Trope as Texte, Parenthèse, Glose, Commentaire followed by Constellation-miroir. An excellent performance.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2012)

Piano: Dmitri Vassilakis

SACD: Pierre Boulez und das Klavier. Cybele 3SACDKIG004 (2012)

Purchase: SACD [Amazon | Presto Music]

No stranger to difficult music, the Greek pianist Dmitri Vassilakis has been playing with the Ensemble Intercontemporain since 1992. This 3-SACD set contains Boulez’s complete solo piano works: all three piano sonatas, Douze Notations pour Piano, Incises, and Une Page D’éphéméride from 2005. Vassilakis begins the Third with “Sigle,” now correctly located in formant 1. This is followed by Trope played as Commentaire, Glose, Texte, Parenthèse; then Constellation. As one might expect from a pianist so closely associated with Boulez, Vassilakis feels at home with the sonata, taking an almost playful approach and letting the resonances ring out with dramatic clarity. The remaining discs contain two interviews by German pianist and producer Mirjam Wiesemann. The first interview is with Pierre Boulez, and was conducted at IRCAM on 31 January 2011. The second interview is with Dmitri Vassilakis, and was conducted at the Cybele studio in Dusseldorf on 17 May 2011. Both interviews are in German, and the liner notes contain no translations.

The hybrid SACDs are recorded in 5.0 multi-channel surround sound, but play in normal players as stereo. The sound quality is excellent, and the 5.0 mixing is free from gimmicks. Unfortunately the packaging is dreadful—flimsy cardboard fold-outs with little consideration for longevity or aesthetics. The set contains an attached booklet, which makes it difficult to access without breaking the spine. And while the liner notes are well-written and informative, the English translation is confusingly organized.

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2015)

Piano: Marc Ponthus

CD: Boulez: Complete Music for Solo Piano. Bridge 9456A/B (2015)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Excerpts]

Following close on the heels of the Vassilakis set, this collection by French pianist Marc Ponthus also features the three piano sonatas, Douze Notations pour Piano, Incises, and Une Page D’éphéméride. Despite the terrible cover—and trust me, it looks even worse up close!—the sonatas are splendidly played, a welcome bridge between the expressionistic performances of Biret and Chen and the “Darmstadt precision” of Henck and Schleiermacher. Ponthus begins the Third with Constellation-miroir and ends with Trope.

|

|

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2017)

Piano: James W. Iman

CD: Iman Plays Schoenberg, Boulez, Webern, Amy. ZeD Classics ZED17001 (2017)

CD: Iman Album I. Métier MSV28627 (2022)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Excerpts]

James W. Iman is an American pianist who specializes in music written since 1945. This recording of the Third Piano Sonata dates to 2017, when it first appeared on the short-lived Belgian label ZeD. In 2022 Métier reissued that album as Iman: Album I through Divine Art. Iman invests the Third with great drama and dynamic range, an uncompromisingly Modernist reading that underscores its prickly atonality. He plays Trope as Parenthèse, Commentaire, Close, Texte followed by Constellation-miroir.

Boulez: Constellation-miroir, from Third Piano Sonata (2017)

Piano: Dmitri Vassilakis

CD: Arnold Schoenberg/Pierre Boulez. Stradivarius STR 37088 (2017)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

On this collection of Boulez and Schönberg, Dmitri Vassilakis plays Dérive 1, Constellation-miroir from the Troisième Sonata, and the world premiere of Fragment d’une ébauche. All the pieces on this disc were recorded in Italy in April, 2017, and are played with complete authority—it’s a shame the Third is incomplete! (Yes, I’m aware of the irony.)

Boulez: Third Piano Sonata (2021)

Piano: Florent Boffard

CD: Boffard: Beethoven, Berg, Boulez. Mirare MIR510 (2021)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

This important album is the first recording of Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata to include the extraits of format 1 published in 2019. The sonata is performed by the French pianist Forrest Boffard, a former student of the great Yvonne Loriod and a member of the Ensemble Intercontemporain from 1988 to 1999. Boffard is one of the few pianists previously familiar with formant 1, having workshopped the material with Pierre Boulez and played it live during the Aldeburgh Festival in 2015. Boffard sets Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata with Beethoven’s “Appassionata” and Berg’s Piano Sonata, three sonatas “contemporary with the historical upheavals that have shaken Europe.” A necessary listen!

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube.

Sonate n°3 de Pierre Boulez: Lecture avec le compositeur

Piano: Pierre-Laurent Aimard

A half-hour video of Pierre Boulez and Pierre-Laurent Aimard playing and discussing the Third Piano Sonata. [French]

Troisième Sonate pour piano (Boulez 1958)

Piano: Pierre Boulez

An audio-only recording of Boulez playing the Third Piano Sonata at Aix-en-Provence on 19 July 1958.

Trope and Constellation-Miroir (Iman 2013)

Piano: James Imam

Performance for the Steinway Society of Western Pennsylvania’s recital series.

Constellation-miroir (Schleiermacher 2013)

Piano: Steffen Schleiermacher

Performance at the inaugural Earle Brown Symposium hosted at Northeastern University, January 2013.

Troisième Sonate pour Piano (Jumppanen 2014)

Piano: Paavali Jumppanen

A performance of Troisième Sonate dating from 2014.

Sonata No. 3 (Gómez 2017)

Piano: Alfonso Gómez

Concert at the Juan March Foundation in Madrid, March 2017.

Florent Boffard: Boulez (Boffard 2021)

Piano: Florent Boffard

Recorded live on 19 January 2021, this hour-long Boulez recital includes the Third Piano Sonata.

Additional Information

Third Piano Sonata Wikipedia Page

This informative page details all three of Boulez’s piano sonatas.

Trope Score

UE sells the score for Trope, and it’s worth peeking at the preview!

Antiphonie Score

The short score for formant 1 may be viewed online at Universal Editions, and contains some interesting information about its troubled history.

“Trope by Pierre Boulez.”

Peter O’Hagan, Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher Stiftung, No. 11 (April 1998), p.29. An informative essay on formant 2 by the pianist and musicologist who started the ball rolling on the eventual publication of Antiphonie. [PDF]

“The Concept of ‘Alea’ in Pierre Boulez’s Constellation-miroir.”

Anne Trenkamp, Music & Letters, January 1976. An informative paper on indeterminacy in the Third Piano Sonata. Sadly, it’s locked behind the JSTOR paywall.

“‘Alea’ and the Concept of the ‘Work in Progress’”

Peter O’Hagen, Pierre Boulez Studies, 20 October 2016. Another good paper, but also behind a paywall.

“Stéphane Mallarmé Created an Ideal Book Never Meant to Be Published”

Marcella Durand, Hyperallergic, 28 March 2020. An essay on Mallarmé’s Livre and its English realization by Sylvia Gorelick.

Selected Books

The Book

By Stéphane Mallarmé. Translated/Realized by Sylvia Gorelick

Exact Change, 2018

To call this a “translation” of Mallarmé’s Livre is to do Sylvia Gorelick a discredit: this is a full-blown reconstruction, a realization of the French poet’s great unpublished work. And may I suggest some background music to play while you make your way through this literary labyrinth?

Publisher’s Description: The Book was Mallarmé’s total artwork, a book to encompass all books. His collected drafts and notes toward it, published only posthumously in French in 1957, are alternately mystical, lyrical and gloriously banal; for example, many concern the dimensions, page count and cost of printing this ideal book. Resembling sheet music, the lines are laid out like a musical score, with abundant expanses of blank space between them. Frequently quoted, sometimes excerpted, but never before translated in its entirety, The Book is a visual poem about its own construction, the scaffolding of a cosmic architecture intended to reveal “all existing relations between everything.”

Pierre Boulez and the Piano: A Study in Style and Technique

By Peter O’Hazan

Routledge, 2017

Publisher’s Description: Peter O’Hagan has given performances of various unpublished piano works by Boulez, including Antiphonie from the Third Sonata and Trois Psalmodies. In this study, he considers Boulez’s writing for the piano in the context of the composer’s stylistic evolution throughout the course of his development. Each of the principal works is considered in detail, not only on its own terms, but also as a stage in Boulez’s ongoing quest to invent radical solutions to the renewal of musical language and to reinvigorate tradition. The volume includes reference to hitherto unpublished source material, which sheds light on his working methods and on the interrelationship between works.

Pierre Boulez: Other Joyce-Related Works

Pierre Boulez Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Pierre Boulez profile.

Répons (1981)

Requiring an orchestra, six soloists, a digital processor and six loudspeakers, Boulez considers this inventive work to use Joycean techniques.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

First Posted: 30 June 2001

Last Modified: 22 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com