Wild Bill Hickok

- At June 18, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Deadlands

0

0

Physically he was a delight to look upon. Tall, lithe and free in every motion, he made and walked as if every muscle was perfection, and the careless swing of his body as he moved seemed perfectly in keeping with the man, the country, the time in which he lived. I do not recall anything finer in the way of physical perfection than Wild Bill when he swung himself lightly from his saddle, and with graceful, swaying steps, squarely set shoulders and well pointed head, approached our tent for orders. He was rather fantastically clad but that seemed perfectly in keeping with the time and place. He did not make an armoury of his waist, but carried two pistols. He wore top-boots, riding breeches, and dark blue flannel shirt, with scarlet set in front. A loose neck handkerchief left his fine firm throat free. I do not at all remember his features but the frankly, manly expression of his fearless eyes and his courteous manner gave one a feeling of confidence in his word and in his undaunted courage

—Libby Custer

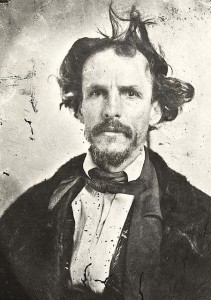

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok (1837–1876)

Statistics

AGL d10, SMT d8, SPT d12, STR d8, VIG d8, PAR 6, TGH 7, Cha +2. Rank: Legend, Fate Chips 5*, Wounds 3/I. Hindrances: Dandy, Disease (Glaucoma). Edges: Ambidextrous, Charismatic, Danger Sense, Dead Shot, Great Luck, Improved Trademark Weapon (Colt Navy), Improved Trademark Weapon (Springfield Rifle), Killer Instinct, Level Headed, Liquid Courage, Marksman, Master (Shooting +2, d10 Wild Die) No Mercy, Quick, Quick Draw, Rapid Loading, Steady Hands, Unique Edge (Dead Man’s Hand), Unique Edge (Epic Gunslinger), Skills: Fighting d8, Gambling d10, Intimidation d10, Investigation d8, Notice d8, Riding d8, Shooting d12+2 (+2 ITW, d10 Wild Die), Stealth d4, Streetwise d6, Survival d10, Tracking d8. Attack: 2x Colt Navy revolvers, Cal .36, RoF 1, DAM 2D6.

Description

Once a vigorous man with a flowing mane of auburn hair and the grace of a wildcat, Wild Bill Hickok has certainly seen better days. His face has been harrowed by years of conflict, his long curls are flecked with gray, and a note of profound weariness sounds in his powerful baritone. Wracked by glaucoma, Hickok’s piercing blue eyes are often concealed by a squint, and he’s been forced to wear blue-tinted spectacles to bear the harsh glare of daylight hours. Having acquired a recent fondness for the bottle, Hickok has discovered that his famously steady hands have begun to tremble, and he occasionally leans on a rosewood cane fashioned from an old cue stick. Still, there’s some fire left in his belly; and while his renowned Prince Albert frock coat appears as frayed as his soul, his six-shooters are well-oiled and fully loaded.

History

James Butler Hickok was born on 27 May 1837 in Homer, Illinois, the fourth child of Pamelia Butler and William Alonzo Hickok. Emigrants from Vermont, William was a bookish man who had wanted to be a Presbyterian minister, while “Polly” was the daughter of one of Ethan Allen’s original Green Mountain boys and the aunt of Benjamin “The Beast” Butler. Committed abolitionists, the Hickok family used their farm as a station on the underground railroad, and the young James—sometimes known as “J.B.”—grew up learning to despise bullies and help the defenseless.

When William died in 1852, the Hickok family fell on hard times. Entrusted by his brothers to hunt for sustenance while they maintained the farm, J.B. developed a reputation as a crack shot, bringing down birds on the wing with a flintlock he’d purchased with his chore money. Finding employment as a muleskinner on the Illinois & Michigan Canal, Hickok soon ran afoul of his supervisor, a local tough named Charles Hudson. Hudson began calling Hickok “Ducky” on account of his long nose and protruding lips. After one too many insults, Hickok knocked Hudson into the canal with a sudden right hook. His supervisor declined to emerge from the canal, and Hickok panicked. Believing he had surely killed the man, Hickok fled to Illinois to escape the law. Along the way, he began referring to himself as “William.” Upon reaching St. Louis, Hickok was notified that Hudson survived. Having tasted adventure, the young man decided to keep on going, and he booked passage on a steamer heading west on the Missouri River. On his way to Kansas, James Butler Hickok decided that he would retain his father’s name.

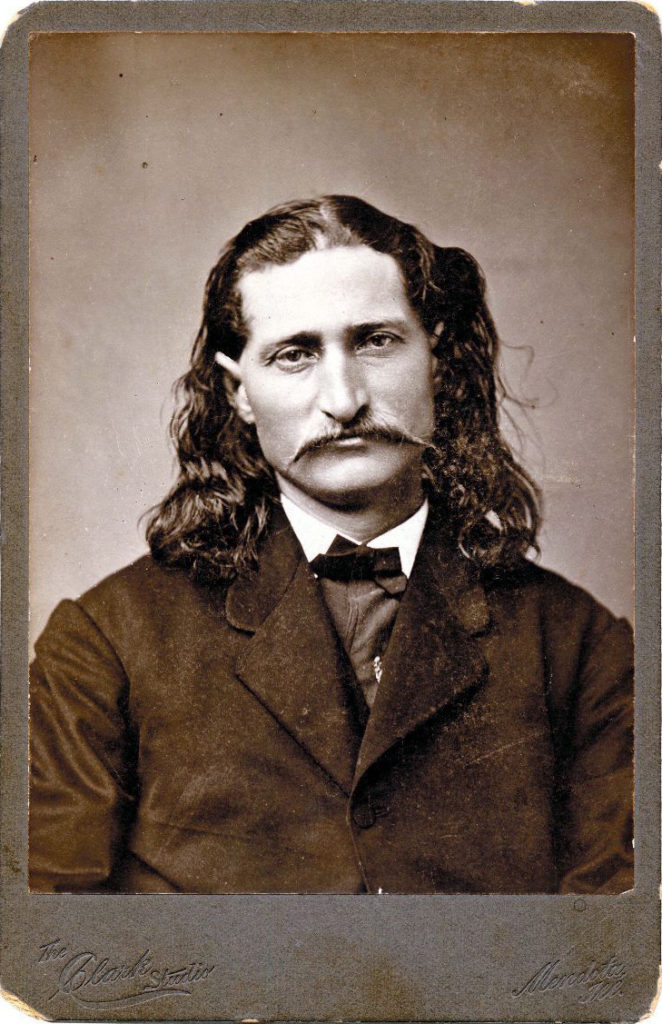

J.B. “William” Hickok in 1858

Bleeding Kansas

Soon after arriving in Kansas, Hickok joined the Free State Army, a militant organization devoted to keeping the soil of Kansas free from the scourge of slavery. Commanded by James Henry Lane, the “jayhawkers” frequently clashed with pro-slavery “border ruffians,” and were not above the occasional holdup or prison break. Soon Lane’s men were calling Hickok “Shanghai Bill,” largely on account of his “slim and supple” form; but also because he was an expert in sneaking up on his enemies and knocking them cold. Hickok soon fell in with John Owen, a Free-State farmer whose half-Pawnee daughter Mary Jane became Hickok’s first love.

With Owen’s recommendation, Hickok was appointed Lane’s bodyguard, and was soon elected the town constable of Monticello Township. He supplemented his income by working as a freighter, and it was during one of these runs Hickok saved a young teamster from taking a beating. That boy’s name was William Cody. Nine years Hickok’s junior, Cody would become a lifelong friend. Unfortunately, soon after returning to Monticello, Hickok’s cabin and crops were put to the torch by pro-slavery bushwhackers. Monticello had become too hot for this young abolitionist, so he bid farewell to John and Mary Jane and moved to Leavenworth.

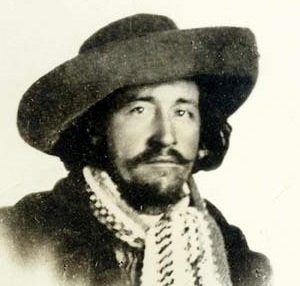

James Henry Lane

Seeking to earn enough money to settle down and invite his family from Illinois, Hickok took a job with Russell, Major & Waddell. Too lanky to serve as a Pony Express rider, Hickok was employed as a stagecoach driver and freighter, working along the Santa Fe trail. During this time he met his hero, the legendary frontiersman Kit Carson. The older man took a liking to this brash jayhawker, and after a night on the town drinking, gambling, and trading war stories, Carson presented Hickok with his Colt dragoon pistol. A few months later, Hickok spent some time with Cody’s family at their “Big House” in Leavenworth, practicing his “quick draw” and learning the feel of a heavy revolver.

In 1860, Hickok was driving freight from Independence to Santa Fe. During this time, two legends were born—his enduring nickname, and the story of his fight with the bear. The first occurred in Independence itself, when Hickok came across a bartender receiving a severe beating after expressing his sympathies for the Rebellion. Despite his Unionist beliefs, Hickok waded in between the man and his tormentors. Firing his revolver in the air he declared, “I’ll shoot the next man who comes at me.” This put an end to the fight. Shortly thereafter a woman expressed her approval as Hickok passed her on the street—“Good for you, Wild Bill!”

The second incident occurred a few months later, when Hickok was driving a small freight wagon to Santa Fe. Rounding a bend, he found a mother cinnamon bear blocking the trail and guarding her cubs. Knowing that few creatures were more dangerous than a riled-up mama bear, Hickok approached the monster with his Colt dragoon and opened fire, placing a bullet into her skull. The subject of many later tall tales, an epic fight ensued. Hickok claims his shot only “enraged” the creature, which then mauled his left arm before he drew his Bowie knife and drove the blade into her throat. Leaving behind a trail of blood as he crawled to his wagon, Hickok barely made it to the next town, nursing a broken arm and several cracked ribs.

The McCanles Fight

After spending a few months recuperating, Hickok was well enough to resume work, but his injuries prevented him from driving. He was appointed assistant stock tender at Russell, Major & Waddell’s new stage line at Rock Creek, Nebraska. The station occupied land leased from a former sheriff named David Colbert McCanles, a former border ruffian who owned several ranches and had developed a reputation as a nasty character. On 16 July 1861, McCanles, his young son William, and his two associates James Woods and James Gordon, arrived at Rock Creek Station to demand the overdue rent. The station master Horace Wellman couldn’t pay, and some harsh words were exchanged. When Hickok attempted to pacify the landlord, McCanles dismissed him as “Duck Bill.” Ignoring the infuriated stable hand, McCanles rattled his shotgun at Wellman’s wife, who was berating him for his ungentlemanly conduct. The moment the shotgun twitched, “Duck Bill” drew his revolver and placed a round in McCanles’ heart. He then shot Woods and Gordon, who both staggered away injured. Woods fell to the ground a few yards away, meeting his end when Mrs. Wellman bashed in his skull with her garden hoe. Suffering only a grazed shoulder, Gordon fled through the sagebrush and vanished from sight. Hickok unleashed Wellman’s dogs and tracked the ruffian down. Finding him cowering by a rock, Hickok added a third man to the butcher’s bill.

McCanles’ son William was the only witness. He told authorities that his father was unarmed, and claimed that Hickok had ambushed the landlord while hiding in the barn. Hickok and Wellman were arrested. With McCanles’ shotgun presented as evidence, the jury decided they acted in self-defense. It was a pattern that would be repeated several times across Hickok’s career.

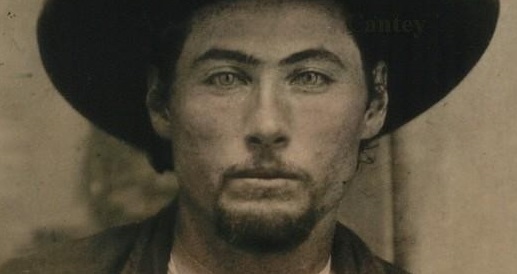

David McCanles

Civil War

No longer welcome at Rock Creek, Hickok decided to follow his father’s abolitionist footsteps. He enlisted in the Union Army as a scout for General Nathaniel Lyon, seeing his first action against General Sterling Price at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. He spent the next year working alternatively as a scout and a Union teamster, and during the Battle of Pea Ridge, Hickok served as a sharpshooter and messenger for General Samuel Curtis. In 1862, he took on his most dangerous assignment yet, volunteering to serve as a spy for General Curtis. Adopting the uniform and role of a Confederate officer, Hickok spend months behind enemy lines, infiltrating the staff of General Price under the guise of a dead Confederate’s brother. During this time, he uncovered information that a rebel spy had been feeding intelligence to Price through her contacts with Union officers in St. Louis. And so, Wild Bill Hickok ended the spying career of one Belle Siddons, a woman he’d meet later in Cheyenne and Deadwood under the name of Lurline Monteverde. He also spent some of his time romancing a Southern woman named Susannah Moore, a Union sympathizer who frequently assisted him behind enemy lines.

Hickok’s spying days came to an end when one of Marmaduke’s corporals recognized him as “that ol’ jayhawker Wild Bill!” He was arrested and detained at a cabin near Fort Scott, Kansas. Sentenced to greet the firing squad at dawn, Hickok was placed under armed guard and locked into a pitch-black room. As fate would have it, a sudden storm blew in from the east, and a flash of lightning revealed a rusty knife lying beneath the cast-iron stove. Retrieving the knife, Hickok freed his bonds, jimmied the locked door, and cut the throat of his closest guard. Dressed in the guard’s uniform, Hickok freed another condemned prisoner and slipped away to the border. Realizing their prisoners had escaped, the Confederates pursued. The Confederates closed in at dawn, but Hickok and his companion crossed the skirmish line under a hail of rebel lead. Turning to his companion in excited relief, Hickok was astonished to find the other man dead; shot through the back as he was crossing the creek to safety. As Union rifles repelled his pursuers, Hickok found none other than William Cody awaiting him. Hickok’s harrowing escape had all the hallmarks of legend, and would be endlessly retold—and embellished—by both men in the coming years.

Cody convinced Hickok that scouting was a more suitable occupation than sneaking around behind enemy lines, and Hickok began working with Cody across Kansas and Missouri. He also accepted work chasing down Union deserters for General John Sandborn. After another brush with death at the Battle of Westport, Hickok quietly took his leave of the Army after Rebel artilleryman Hamish Leadbetter placed General Curtis in his grave. Reserving his farewells for only his closest friends, he departed Cody and eventually found his way to Springfield, where he renewed his acquaintance with Susannah Moore.

The Tutt Duel

Miss Moore wasn’t the only familiar acquaintance awaiting Hickok in Springfield—there were also his old friends Trouble and Controversy. Soon after arriving to town, Hickok fell in with a Confederate deserter named Davis Tutt. Their relationship quickly soured, with each man accusing the other of romantic indiscretion. Tutt claimed that Hickok sired a bastard on his sister, while Hickok accused Tutt of pressing his suit upon Susannah Moore. These tensions finally came to a head during a game of poker at Lyon’s Hotel, where Tutt was loaning other gamblers his money and openly encouraging them to beat Hickok. Unfortunately for his rival, Hickok was on a winning streak, and Tutt lost his stake. Snatching Hickok’s gold pocket watch from the table, Tutt claimed it as collateral for a past debt. This initiated a few days of “negotiation.” Every time Hickok offered to pay the original “debt,” Tutt increased the amount. Eventually Tutt’s friends dared him to humiliate Hickok by openly wearing the watch in public.

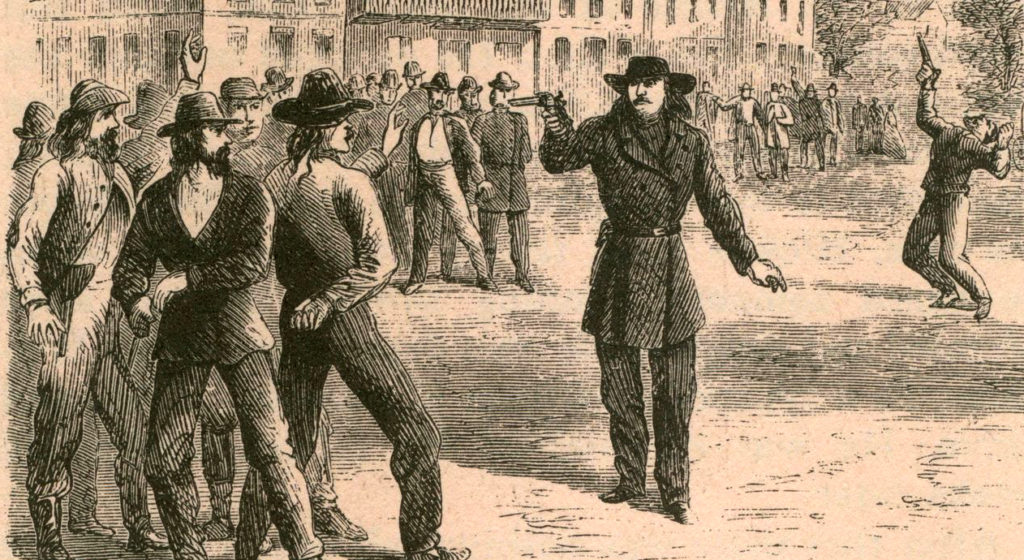

Having had enough of Tutt’s shenanigans, Hickok marched to the town square with his Colt Navy loaded and ready for use. Stopping some seventy-five yards away from Tutt, he demanded that his watch be returned. As Tutt reached for his revolver, Hickok drew first, calmly balanced the Colt on his arm, and pulled the trigger simultaneously with his opponent. Only Hickok’s bullet struck true, driving through Tutt’s ribs to explode his heart. Tutt’s final words were, “Boys, I’m killed!”

Davis Tutt

Hickok was arrested and tried for manslaughter, but the judge agreed it was justifiable homicide. A few weeks later, journalist and former Army colonel George Ward Nichols interviewed Hickok. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine ran a piece on the duel, claiming that “Wild Bill Hitchcock” was the author of hundreds of such gunfights. Although Nichol’s piece misspelled his name, it launched Hickok’s reputation as a living legend. Most of Hickok’s contemporaries recognized it as hogwash, and he lost the election for city marshal of Springfield. He also lost Susannah Moore, who never forgave him for gunning down Davis Tutt.

Hickok spent the next few years wandering the Midwest. In 1866 John Owen landed his old comrade the position of deputy U.S. Marshal at Fort Riley, a lawless army outpost in northern Kansas. Rounding up deserters and arresting embezzlers, it was inglorious work, but at least he remained on the right side of the law. It was here that Hickok acquired the habit of always walking down the middle of the street, the better to see all possible evildoers. Muddy boots seemed like a fair trade to head off an ambush.

Hickok was present when the 7th Cavalry Regiment was organized at Fort Riley to deal with the increasing threat of hostile Indians. He quickly befriended George Armstrong Custer and his wife Libby, and became re-absorbed back into military life. Scouting again for the Army, Hickok was recommended for several high-profile assignments by William Cody, and served under such luminaries as Philip Sheridan and Winfield Scott Hancock. In between 1867–1868, he served during engagements with the Cheyenne and allied tribes, scouting for Custer’s 7th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry “Buffalo Soldiers,” and Carr’s dashing 5th Cavalry. After a Cheyenne lance became embedded in his thigh, Hickok returned home to visit his sick mother. Recuperating from his latest injury, Hickok planned his next move.

Hays City

In 1869, Hickok was appointed deputy U.S. Marshal of Hays City, a small railway town near Fort Hays, Kansas. Employed to keep the peace between soldiers and the town’s unruly population of buffalo hunters, Hickok enacted a “no guns” policy and attempted to treat everyone as fairly as possible—he even arrested General Custer’s brother Tom for shooting out the streetlights on New Year’s Eve! Elected sheriff of the county, Hickok attempted to avoid controversy, but was forced to kill two men when they attempted to outdraw the famous gunslinger. Although he was acquitted of both killings, his aggressive policies earned him few admirers, and he lost the next election. Although he still counted himself a friend of General Custer, his relationship with the 7th Cavalry became increasingly strained. Hickok finally wore out his welcome in Hays when drunken troopers from the 7th Cavalry accosted him in a saloon. Held to the ground by Private Jeremiah Lonergan, Private John Kyle placed his revolver against Hickok’s head and pulled the trigger. When Kyle’s pistol misfired, Wild Bill Hickok returned the favor with a pair of fatal bullets.

1870 Illustration of Wild Bill’s duel with Tutt

Abilene

Hickok’s next job as a lawman was in Abilene. He was hired to replace marshal Tom Smith, who had been killed in an ambush while serving papers to a local homesteader. A cattle town known to become boisterous when the drovers arrived, Abilene attracted many of the same drunken cowboys who plagued Hays, and Hickok responded by again posting a strict “no guns in town” policy.

While in Abilene, Hickok also met and courted circus performer Agnes Thatcher Lake, the owner and manager of the Hippo-Olympiad and Mammoth Circus. Eleven years older than Hickok, Lake was a German-born actress, dancer, lion tamer, and tightrope walker. Two years prior, her husband Bill Lake—the “Napoleon of Showmen”—was murdered by an angry customer who had been caught sneaking into the circus without paying admission. His widow took over the reins, and became the first woman in America to own a traveling circus. She met Hickok when she visited the marshal’s office to acquire the proper permits, and was immediately struck by his dignified appearance and overall gravitas. Hickok attended several performances, at first “professionally,” but soon finding himself drawn to the exotic woman and her feats of daring. The two were obviously attracted to each other, but both were busy managing their own unruly empires.

Abilene proved no different than Rock Creek, Springfield, or Hays City, and soon Hickok was again at the center of a conflict. This time it was a former Confederate soldier named Phil Coe, the owner of the Bull’s Head Saloon and a frequent rival of Hickok’s across the poker table. A friend of John Wesley Hardin, who was staying in Abilene under the name Wesley Clemmons, Coe had painted a charging bull on the side of his saloon—complete with a formidably erect penis! Acting on behalf of Abilene’s concerned citizens, Hickok asked Coe to remove the offending member from the painting. When Coe refused, Hickok opened a can of paint and castrated the bull himself. As tensions mounted between the lawman and the owner, Coe began threatening violence, remarking he once “killed a crow on the wing.” Hickok replied coolly, “Did the crow have a pistol? Was he shooting back? I will be.”

His remarks were prophetic. On 5 October 1871, Coe opened fire on a stray dog barking in the street near Hickok. The marshal ordered Coe to hand over his gun; but when Coe jerked its barrel towards Hickok, Wild Bill placed two rounds in his stomach. Unfortunately, Hickok’s deputy marshal had just leapt forward to aid his boss. Wired on adrenaline, Hickok dropped the hammer again, killing his own deputy, Mike Williams.

Hickok was devastated. Although he was found innocent of wrongful death, he had murdered his friend and fellow lawman. Hickok wrote Williams’ family and arranged to pay for the deputy’s funeral. He had also begun to question his eyesight—why didn’t he recognize Williams immediately? All he saw was a blur, and reacted.

Meantime, Abilene’s reputation for lawlessness ironically increased, actually compounded by the presence of its notorious lawman. As word of Coe’s death spread across the West, gunslingers and miscreants announced their intentions to gun down the famous Wild Bill Hickok. On more than one occasional Hickok was forced to ambush these brash comers, preemptively disarming them and sending them back home with their tails between their legs. Having grown weary of drunken cowboys and the sound of gunfire in its streets, Abilene decided to close its doors to cattle drives, and Hickok was quietly relieved of his duties. With Lake’s circus touring the country and his reputation as a marshal permanently stained, Hickok increasingly indulged his fondness for whiskey and cards.

Brief Unhappy Stage Career

In 1872, Buffalo Bill Cody teamed up with Texas Jack Omohundro in Chicago to produce his first “Wild West” show, The Scouts of the Prairie, produced by the dime-novel hack Ned Buntline. A year later, this became Scouts of the Plain, and Cody asked his old friend Wild Bill Hickok to portray himself on stage. Unable to act, gripped by stage fright, and irritated by show business in general, Hickok fared poorly. Although he came to appreciate New York’s many saloons and finer hotels, the show itself became a tedious burden, and Hickok began paying pranks—going off script in the middle of a performance, shooting the troupe’s Indians with blanks, and replacing bogus “stage-whiskey” with the real deal. Once he even drew his revolver and shot out a spotlight that was irritating his eyes. While the crowds were generally delighted by Wild Bill’s antics, Buffalo Bill was less amused, and Hickok and Cody amicably declared the experiment a failure. Once more looking out for his older friend’s interests, Cody raised a parting gift of $1000, and the cast bid Hickok farewell in Rochester.

Left to right: Elisha P. Green, Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody, Texas Jack Omohundro, Eugene Overton.

Taken in 1872 by R.H. Forman Photography.

Cheyenne

Returning to his pattern of aimless wandering, Hickok frittered away his earnings on whiskey and cards. He spend some time renewing his acquaintance with Agnes Lake in Rochester, then paid a visit to an old Hays friend named Charlie Utter, now living in Colorado. Once the money ran out, Hickok worked for a spell as a house gambler in Kansas City. Soon Hickok realized that his eyesight was truly failing him—bright lights had become painful, and he had trouble making out contrasts, especially when the lighting was poor. A visit to a doctor confirmed his suspicions, and Hickok was diagnosed with glaucoma and “ophthalmia,” or severe conjunctivitis.

In 1875 Wild Bill Hickok arrived in Cheyenne. Spending his time hunting, trapping, and gambling, as his eyesight continued to deteriorate, Hickok found himself fending off young challengers with tall tales and broad-daylight shooting contests. Always cagey when taking his leisure, his policy of sitting with his back to the wall became an obsession, and he soon took to wearing tinted glasses in daylight. Hearing that Lake’s circus was back in town, Hickok paid her a visit, and their on-and-off courtship finally blossomed into a genuine romance.

In March 1876, James Butler Hickok and Agnes Thatcher Lake were married in Cheyenne. They spent the next few weeks with her family in Ohio. Returning West without his bride, Hickok promised he’d strike it rich in the Black Hills, build a house, and send for Agnes to join him. It was time to settle down. Hickok returned to Cheyenne in April 1876, his heart ready to heal and his soul yearning for redemption. Now, all he had to do was earn enough money to make the dream a reality. Surely a run of lucky games would set him up?

Agnes Darling, if such should be we never meet again, while firing my last shot, I will gently breathe the name of my wife—Agnes—and with wishes even for my enemies I will make the plunge and try to swim to the other shore.

—Wild Bill Hickok, letter to Agnes, Summer 1876

The Future

The setting of Deadlands 1876 features Wild Bill Hickok during the last few months of his life; and his fate is one of the West’s most enduring legends. After spending the summer knocking about Cheyenne, Wild Bill Hickok joined Charlie Utter’s famous wagon train heading for Deadwood. It was here that he made the acquaintance of Martha “Calamity Jane” Cannary. Finding her to be a loutish drunkard, Hickok had little time for her antics, but that didn’t stop Jane from inserting herself into Hickok’s business at every opportunity. Indeed, years later Jane would claim the two shared a bed, and were even secretly married. It was another one of her colorful lies, of course, but history remembers their imaginary relationship much more than Hickok’s actual marriage!

If Hickok would have stayed in Cheyenne, perhaps he would have rescued himself from his own self-destructive urges. But a place like Deadwood had little to offer in the way of salvation—lawless and opportunistic, it is a town that attracts the desperate and the deluded, a place where dreams die gasping for breath in the muddy streets. After unsuccessfully trying his luck prospecting, Hickok sank deeper into the doldrums of despair, drinking and gambling and fending off various intrusions—provocations from fame-hungry gunslingers; attempts by Calamity Jane to ensnare his affections; and most irritating of all, constant requests by Deadwood officials to pin a badge on his chest.

Wild Bill Hickok met his ignoble end on August 2nd at Nuttall and Mann’s No. 10 Saloon, once of his favorite gambling haunts. Prevented from taking his usual position with his back against the wall, he barely noticed one Jack McCall, a strange and nervous man he had beaten at poker the day before. Nursing some unfathomable moral injury in his tormented heart, the coward Jack McCall placed his revolver against the back of Hickok’s head and pulled the trigger, shouting “Damn you, take that!” Hickok was dead in a heartbeat, the bullet passing through his skull to lodge in the wrist-bone of fellow gambler, Captain William Massie. In Hickok’s possession was the famous “dead man’s hand”—the ace of spades, ace of clubs, eight of spades, eight of clubs, and one unknown and oft-disputed card.

Aftermath

Colorado Charlie Utter arranged for Hickok’s funeral, auctioning off the marshal’s guns to raise the required funds. After a failed attempt to bring McCall to justice in Deadwood, the coward escaped to Wyoming. He was apprehended in Laramie and shipped to Yankton for trial, where he was found guilty of murder. As the noose was placed around his neck, Jack McCall uttered his last words: “Draw it tighter, Marshal.”

In 1879, Charlie Utter relocated Hickok’s body to Mount Moriah Cemetery above Deadwood. Agnes Lake remarried soon after, and Calamity Jane became increasingly insistent that she was the true love of Wild Bill’s life. After a period spent as a laundress in a Black Hills brothel, Jane drank herself to death in Terry, South Dakota in 1903. Her dying wish was to be laid to rest beside Wild Bill. She resides there to this day, her ghost surely laughing as history fades into legend, drawing them closer in death than they were ever in life.

Calamity Jane at Hickok’s grave

Special Abilities

Hindrance: Dandy

Wild Bill Hickok is a bit of a dandy. He enjoys dressing in fancy duds, he keeps his hair long and well-oiled, and he has an unusual penchant for cleanliness—Hickok is famous for requiring a daily bath! Every day that Hickok is deprived of these amenities makes him increasingly irritable and cranky, lowering his Charisma by one point until a –2 Charisma is reached.

Hindrance: Disease (Glaucoma)

Bright light hurts Wild Bill’s eyes, and he has trouble seeing, particularly under dim lighting. If he is without his tinted glasses during the day, or is forced to fight under gloomy conditions, he loses the benefits conferred by his Improved Trademark Edges.

Unique Edge: Epic Gunslinger

Wild Bill is more than a fast draw; his ability to shoot from the hip with deadly accuracy is legendary, even among gunfighters. Once per day, Wild Bill Hickok may use a d20 for any single Shooting roll.

Unique Edge: Dead Man’s Hand

Fate is a fickle mistress; and Hickok’s destiny cannot be changed. However, his legendary death has cast its shadow backwards, and provides Hickok with a charmed life leading up to that final encounter at No. 10 Saloon. If Wild Bill draws any black ace or eight as his Action Card, it is treated like a Joker.

Wild Bill Hickok’s Possessions

Wild Bill Hickok has managed to collect numerous guns during his multifaceted career, but these four are particularly notable.

Kit Carson’s Colt Dragoon

Presented to Wild Bill Hickok in 1859 by Kit Carson, this old dragoon is the revolver that Hickok used to kill his first man, David McCanles. Long since replaced by a pair of Colt Navy revolvers, Hickok nevertheless keeps it clean and oiled in a special box.

Statistics

1848 Colt Model 1848 Percussion Army Revolver, “Dragoon” Third Model. Caliber .44, Range 10/75/150, Capacity 6, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8. In Wild Bill Hickok’s hands: Trademark Weapon, +1 Shooting bonus. For Deadland campaigns set after Hickok’s murder, this gun may be invested with the arcane power of Righteous Fury. Any time a human being is justifiably killed with a round from this Dragoon, all subsequent rounds remaining in the cylinder are invested with the Smite power.

Colt Revolvers

Wild Bill is never without his pair of Colt Navy revolvers, nickel-plated, engraved, and featuring ivory grips.

On the plains every man openly carried his belt with its invariable appendages, knife and revolver, often two of the latter. Wild Bill always carried two handsome ivory-handled revolvers of the large size; he was never seen without them.

—George A. Custer

Statistics

1851 Colt Navy revolver. Caliber .36, Range 10/25/100, Capacity 6, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d6. In Wild Bill Hickok’s hands: Improved Trademark Weapon, +2 Shooting bonus. For Deadland campaigns set after Hickok’s murder, this gun may be invested with the arcane power of Epic Gunslinger. Once per day, each may grant the shooter a d20 Shooting die.

Schofield Revolvers

This pair of finely-engraved Smith & Wesson “Schofield” revolvers was presented to Hickok by Texas Jack Omohundro. Still in their case, they have never been fired.

Statistics

Smith & Wesson Model No. 1, “Schofield” revolver. Cartridge, single-action, top-break. Caliber .44, Range 10/50/100, Capacity 6, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8.

Springfield Rifle

Hickok’s must trusted rifle, this longarm is an 1870 Allin “trapdoor” conversion of an 1863 Springfield musket. Over the years, the stock was refitted with a “sloped butt” Kentucky rifle buttstock, and the barrel was replaced with a rifled 29 5/8” barrel, placing its length halfway between Springfield’s traditional carbine and the rifle variants. Wild Bill himself carved “J.B. Hickok” into the stock with his knife. This rifle is slated to accompany Hickok in his coffin. (Because no photographs of this rifle are available, the picture below is the standard carbine model.)

Statistics

Springfield Model 1870 Carbine, Allin conversion. Hinged breechblock. Fitted with a Kentucky-rifle style buttstock. Caliber .50-70, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10. In Wild Bill Hickok’s hands: Improved Trademark Weapon, +2 Shooting bonus.

Smith & Wesson Model No. 2

This small revolver is one of Hickok’s holdouts, and is included here for one reason only—it is the gun he was carrying when shot down by the coward Jack McCall.

Statistics

Smith & Wesson Model No. 2, “Old Army.” Serial Number 29963. Cartridge, single-action, tip-up. Caliber .32, Range 10/25/100, Capacity 6, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 1d4+1d6. Notes: For Deadland campaigns set after Hickok’s murder, this gun may be invested with the arcane power of Dead Man’s Hand. If a character using this gun draws any black ace or eight as her Action Card, she may spend a Fate Chip to transform that card into a Joker.

Other Firearms

According to Joseph Rosa writing for Wild West magazine, Wild Bill Hickok also owned a converted .44-caliber Colt Army Model 1860, a .36-caliber Navy with the inscription “J.B. HICKOK, 1869” on the back strap, and a pair of .41-caliber Williamson dual-ignition derringers. Other credible sources claim he owned a pair of .38 cartridge-converted 1851 Colt Navy revolvers in 1875; but whether these were separate guns or conversions of his beloved .36 percussion revolvers is not known.

Campaign Inclusion

The Wild Bill Hickok of Deadlands 1876 is a washed-up gunfighter, a haunted veteran drowning his ghosts in whiskey and regret. Maybe he can earn enough money to build that house and bring Agnes to his side; but every day he spends at the faro table is one more day this dream fades to another shadow. To say that Hickok has premonitions of his own death is to state the obvious—he’s doing everything he can to commit a slow form of suicide. Even the letter he carries in his pocket is an admission of his own imminent demise.

Current Whereabouts

The current location of Wild Bill Hickok is up to the Marshal to decide, whether he’s residing at Dyer’s Hotel in Cheyenne, encamped near Deadwood, or even en route to the West from his honeymoon in Ohio. Historically, Hickok departed Cheyenne with Charlie Utter on 27 June 1876, arrived in Deadwood in July, and was killed on 2 August 1876.

Roles

Wild Bill Hickok may be nearing the end of his tumultuous life, but his powers as a gunslinger are undiminished, and his sense of honor remains intact. Having made a silent pledge to himself never to take another man’s life, Hickok may occupy the role of the doomed hero, the sinner ready for redemption, or the lawman teased out of retirement for one final task. No matter what role he occupies, however, the Marshal should ensure he meets his proper fate—gunned down in the back by a deranged coward.

Sources & Notes

Historical Note

Wild Bill Hickok is one of the West’s most legendary figures, and there have been countless attempts to portray his life, from the original hyperbole of Nichols’ Harpers article to sober biographies excavating the meagre veins of historical authenticity. This Deadlands 1876 biography attempts to tread the middle ground, generally sticking to the historical record but embracing certain embellishments in the John Ford “print the legend” tradition. For instance, Hickok’s fight with the cinnamon bear was probably apocryphal, and there are so many versions of the McCanles gunfight they may seem like unrelated incidents. Did Hickok make the famous comment about the crow shooting back? Probably not; but it sounds good. I also retained the historically unlikely fistfight with Charles Hudson, and conflated the numerous tales of Hickok’s “narrow escape from Confederate lines” into a single narrative. Obviously, some changes have been made to accommodate the alternate timeline of Deadlands 1876; mostly re-assigning former Confederates to the ranks of deserters, and finding excuses to keep Hickok away from the ongoing Civil War. His relationship with Belle Siddons is my own speculation; but they were both spies on the opposite sides of the Missouri lines, so it’s certainly possible!

Sources

Books

The principal source for this Deadlands biography is Tom Clavin’s Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter. Many of the details I describe above were drawn from this wonderful book, which has a refreshingly open attitude about the perils of historical accuracy, and takes distinct pleasure in making its own speculations. Clavin’s biography is also an excellent resource for the Wild West in general. Limited by the lack of accurate information regarding Hickok’s biography, Clavin fills in the blanks by elaborating on Hickok’s surroundings, and the book contains many colorful details about the people, places, and events relevant to contextualizing Wild Bill. General Lane, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Agnes Thatcher Lake are richly developed as characters, battlegrounds and cattle towns are placed in historical context, and the politics of frontier law are explicated in detail. Also of use was Joseph Rosa’s They Called Him Wild Bill: The Life and Adventures of James Butler Hickok. Considered the “classic” book on Wild Bill, Rosa’s painstaking research forms the backbone of many contemporary studies, including Clavin’s.

Articles

I found Frederick J. Chiaventone’s biographical sketch of Hickok to be informative and well-written, and I also consulted the Wild Bill Hickok page on Legends of America and Bob Boze Bell’s True West article The Truth About Wild Bill. I generally avoided Wild Bill Hickok’s Wikipedia page. It is quite disorganized, and in need of an extensive rewrite. The American Cowboy Chronicles offers numerous contemporary newspaper reports about Hickok, most of them unflattering. Legends of America hosts Nichol’s original Harpers’ article on Hickok. I used Jeff Broom’s award-winning article Wild Bill’s Brawl with Two of Custer’s Troopers from Wild West magazine to flesh out the Hays City fight. Joseph Rosa’s Weapons of a Pistoleer was essential in developing Hickok’s gun collection. Ben Roman’s Field & Stream article Is This the Gun Wild Bill was Carrying When He was Murdered in 1876? was useful to describe the Smith & Wesson Model #2 purportedly in Hickok’s possession when he was shot by the coward Jack McCall.

Cinema

The Wild Bill Hickok of Deadlands 1876 is inspired by Keith Carradine’s unforgettable portrayal in HBO’s Deadwood. Hickok’s “Can’t you let me go to hell the way I want to” speech is required viewing, and features Dayton Callie’s nuanced Charlie Utter, one of the great unsung heroes of Western cinema. And I suppose I should mention Walter Hill’s 1995 film, Wild Bill, starring Jeff Bridges as Hickok. This is a truly awful movie; it’s hard to describe how bad it is without making it sound perversely appealing! This is a movie in which news of a “gargantuan gold strike” a few miles from Deadwood literally evacuates the entire population of the town, giving Wild Bill and Calamity Jane the opportunity to fuck passionately on a poker table while Battle Hymn of the Republic sounds on the player piano; which distracts Hickok just in time for Jack McCall to arrive with a gang of hired killers; who are soon gunned down by Wild Bill in slow-motion as he discharges twenty-four continuous rounds from his pair of six-shooters without reloading. This is a movie where Hickok’s sessions at an opium den trigger flashbacks filmed in high-contrast black and white video, apparent “found footage” in which mystical Indians prophecy his death. This is a movie in which Christina Applegate turns in a better performance than John Hurt, Ellen Barkin, and Jeff Bridges! The only saving grace in the entire film is the brief appearance of Buffalo Bill, played by—wait for it—Keith Carradine! Speaking of Buffalo Bill, you can’t go wrong watching Robert Altman’s magnificent 1976 movie, Buffalo Bill and the Indians. Although Wild Bill Hickok is not in the film, I’ll take any opportunity I can get to promote this underrated classic.

Deadlands Sourcebooks

The “official” take on Wild Bill Hickok as a Deadlands character is found in Shane Lacy Hensley’s Marshal’s Handbook. The vanilla rules cast Wild Bill as one of the Harrowed, having heaved himself up from Mt. Moriah Cemetery seeking vengeance for his death. If a Marshal decides to use this version of Wild Bill, hopefully the preceding profile can help flesh out the details of Hickok’s life, offer alterative statistics, and place a few famous six-shooters in his cold, dead hands!

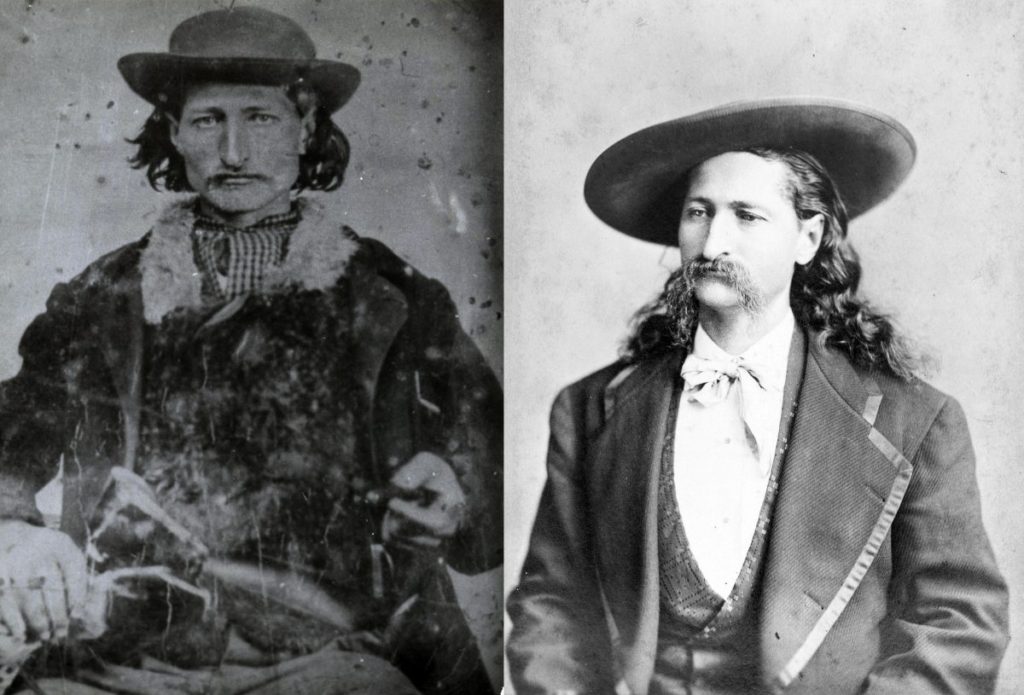

Images

All of the images of Wild Bill and his contemporaries are authentic, and are drawn from various sources across the Web, including the Library of Congress, The Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Wikimedia Commons, and Legends of America. The photographs of his firearms, however, take some necessary liberties. The photograph of the twin Colt revolvers was borrowed from the Connecticut State Library. It is likely that Hickok owned several pairs of Colt revolvers throughout his life, and Rosa reports that he carried a pair of .38 conversions while in Cheyenne. The “Kit Carson Dragoon” was lifted from Rock Island Auctions. The Springfield carbine is also from Rock Island Auctions, and represents the “vanilla” model. The engraved Schofield is actually a rare Number 1 with the Kelton safety. According to Rosa, Texas Jack Omohundro gifted Hickok with a pair of Number 3 Schofield revolvers, but there’s no evidence they actually existed. I looked for engraved No. 3, but none matched the beauty of this image from Rock Island Auctions, so I used it despite the possible anachronism. Uberti did sell a Texas Jack Tribute Schofield, but it sold out long ago! The Smith & Wesson No. 2 is reportedly authentic, and Bonham’s Auctions placed it up for bidding in 2013.

Young man, never run away from a gun. Bullets can travel faster than you can. Besides, if you’re going to be hit, you had better get it in the front than in the back. It looks better. […] When a man believes the bullet isn’t moulded that is going to kill him, what in hell has he got to be afraid of?

—Wild Bill Hickok to Leander Richardson of the Springfield Republican, 1876

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 18 June 2019

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

PDF Version: [Coming Soon]