Borges Music – Piazzolla “Borges & Piazzolla”

- At August 15, 2018

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

To rhythmic playing, he could tell

Stories of the things he had seen

Beneath the awnings of Adela

And in the brothels of Junín.Now he is dead, and with his death

Such memories have been put to rest

Of lost Palermo, its sad lots,

And of the dagger at his breast.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Milonga of Don Nicanor Paredes”

Borges & Piazzolla (1997)

|

|

|

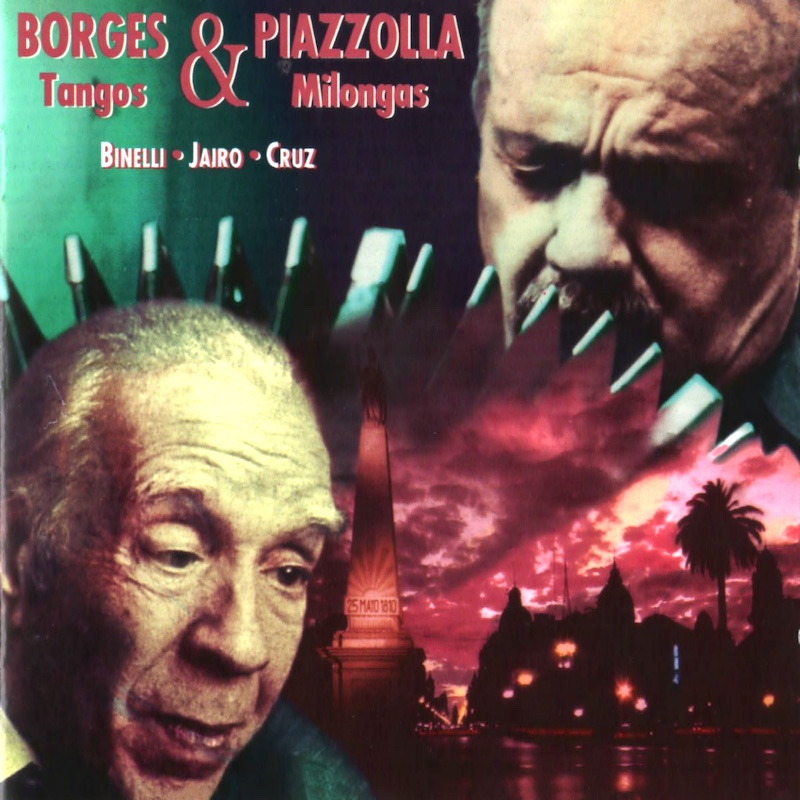

Borges & Piazzolla: Tangos & Milongas (1997)

a.k.a. Borges & Piazzolla: El Tango (2011)

CD: Milan 5050466 3100 2 6 (1997)

Reissue CD: Warner Brothers 4 3 00993602 (2011)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon]

Online at: Youtube [Album Playlist]

Track Listing

1. El tango (Musical poem; 6:21)

2. Jacinto Chiclana (Milonga; 3:01)

3. Alguien le dice al tango (Tango; 3:27)

4. El títere (Milonga tanguera; 2:20)

5. A don Nicanor Paredes (Milonga; 3:45)

6. Oda íntima a Buenos Aires (Porteña ode; 2:36)

El hombre de la esquina rosada

(A suite for 12 instruments, narrator, and singer.)

7. I. Aparición de Rosendo (3:47)

8. II. Rosendo y la Lujanera (2:15)

9. III. Aparición de Real (3:21)

10. IV. Milonga nocturna (2:48)

11. V. Bailongo (1:15)

12. VI. Muerte de Real, VII. Epílogo (4:43)

Musicians

Astor Piazzolla, Music and arrangements

Jorge Luis Borges, Text

Jairo, Voice

Lito Cruz, Narration

Daniel Binelli, Bandoneón

Julio Graña, Solo violin

Andrés Spiller, Solo oboe

Sergio Balderrabano, Piano

Arianna Ruiz Cheylat, Harp

Diego Sánchez, Cello

Benjamin Bru Pesce, Viola

Brigitta Danko, Second violin

Martín Vásquez, Electric & Spanish guitar

Enrique Guerra, Double bass

Omar Angel Frette, Percussion

Héctor Gerardo García, French Horn

Released in 1997 by Milan Records, Borges & Piazzolla: Tangos & Milongas is an all-star re-envisioning of the classic El tango album from 1965. The compact disc features bilingual liner notes which reprint Piazzolla’s commentary from the 1965 recording of El tango, along with new remarks by Laura Escalada Piazzolla, María Kodama, Daniel Binelli, and Envar el Kadri. Also included are brief biographies of Daniel Binelli, Jairo, and Lito Cruz. Unfortunately, the lyrics are not included.

In 2011, the recording was reissued by Warner Brothers International. Containing the same contents as the Milan CD, they changed the name to Borges & Piazzolla: El Tango. While this may be more accurate, it’s caused hopeless discographical confusion—numerous sources now describe this 1997 remake as a reissue of the 1965 original! On the bright side, the 2011 version includes a blurb from yours truly on the back of the CD case, translated into French, no less! (I seem smarter in French.) Somewhere between 2011 and the present day, the artwork was altered to remove the names of Binelli, Jairo, and Cruz from the cover—a tragic neglect of three vital artists!

Comments

When I set out to create a Borges site in the mid-nineties, I had no idea I’d be one day reviewing a tango album. My sole exposure to the music of Astor Piazzolla was the Five Tango Sensations E.P. by Kronos Quartet, and the only reason I had purchased that was because Salome Dances for Peace and Black Angels had (correctly) convinced me that Kronos Quartet could do no wrong. As I expanded the Garden of Forking Paths to include Borges-related music, I naturally discovered his connection to Astor Piazzolla, so I ordered Borges & Piazzolla.

Back before the advent of digital music and Amazon Prime, one had to wait for gratification, and the compact disc arrived a few weeks later. Popping it into my Sony Discman, I gave it a preliminary hearing as I worked, just to absorb its musical textures. Too distracted to pay close attention, I decided to give it a more thorough review at a later date.

The following night I went out on the town, and as fate would have it, I was carousing with friends at a karaoke bar. (OK, it’s not exactly stabbing a gaucho to death in a bordello, but still.) On my walk home I started up my Discman, thinking it was loaded with a Beck CD. (Am I dating myself? I feel like I’m dating myself.) Much to my surprise, Piazzolla’s “El tango” began. Maybe it was the chilly, moonlit night; maybe it was the pre-dawn streets of the deserted city; maybe it was the ungodly amount of beer and whiskey I’d consumed—but suddenly the album gripped me and wouldn’t let go. I sat down on the steps of the local library and finished the entire recording, mesmerized by visions of knife fights and mysterious caudillos. After that, Borges & Piazzolla became one of my favorite albums, opening the door to a musical world I barely knew existed. In a roundabout way, it even led to my love of flamenco.

El Tango Redux

Borges & Piazzolla is a remake of an earlier recording. In 1965, Jorge Luis Borges and Astor Piazzolla collaborated on an album of tangos and milongas called El tango. Although the collaboration was less than harmonious, the album was a success, and produced a few of Piazzolla’s most enduring songs. In 1996, Emmanuel Chamboredon and Envar el Kadri commissioned a new recording of El tango to be made with modern recording technology. To assemble and conduct the sizable musical cast, Daniel Binelli was selected—the bandoneón player who worked with Piazzolla on the original record. The result was Borges & Piazzolla, featuring the Argentine singer Jairo, the Chilean actor Lito Cruz, and Daniel Binelli on the bandoneón.

Like the original, Borges & Piazzolla features six tangos and milongas followed by a suite based on Borges’ short story “El hombre de la esquina rosada.” Combining elements of a tango orquesta típica with a classical chamber ensemble, Borges & Piazzolla calls for a narrator, a singer, and twelve musicians. Often these types of mixed productions sound great in concert, but translate poorly to recording, where they sound muddled or flat. Fortunately, that is not the case with Borges & Piazzolla, which is a masterpiece of production. The instruments feel individually distinct but maintain presence and warmth, the lush vocals are positioned perfectly in the mix, and everything resonates with vitality. Borges & Piazzolla is a wonderful accomplishment, one of those rare albums that seems truly charmed, brimming over with exuberance, wit, and passion.

Borges & Piazzolla opens with the ambitious “El tango.” Conceived as a “musical poem,” the piece opens tentatively, piano and bandoneón trading querulous riffs before erupting into a lilting dance. A fragile violin enters, and the dance continues until everything drops away but the piano, a dark pulse vamping across its lowest register. Plucked strings add to the tension, creating the stage for Lito Cruz’s narration. His reading of Borges’ poem “El tango” is appropriately theatrical, each “¿Dónde estarán?” delivered with increasing urgency, his guttural accent carving out the words with gusto. The restless music prowls around the stanzas, punctuating them with outbursts of color and texture—nails are scratched across metal güiros, lunatic glissés are gleefully ripped from shrieking strings, and instruments are thumped for percussive effects.

While Piazzolla instructed his band in Rough Dancer to sound like half-drunken musicians playing in a whorehouse, Binelli’s tangueros are more suited for a madhouse. It’s clear from the beginning that no one is interested a slavish reproduction of El tango. In his liner notes, producer Envar el Kadri claims their intention was to “rescue” the original album; an interesting and revealing turn of phrase. Like good-natured thieves stealing a relic from a museum and restoring it to the people, they seem hell-bent on liberating El tango from its own historical gravitas. A complete reinvention of the original, Borges & Piazzolla explodes with new life.

After the unbridled energy of “El tango,” we are returned to earth with the milonga “Jacinto Chiclana,” its beautiful melody threaded through a rolling Spanish guitar. This marks the first appearance of Jairo, a singer with a résumé that includes Jairo canto a Borges. Twenty years older than when he recorded that album, his seductive voice has aged beautifully, and he touches every lyric with trembling passion. As the guitar is swept away by a soaring violin, Jairo recites the middle stanzas as spoken-word poetry, underscoring the drama of Borges’ verse:

habrá pisado la tierra.

Nadie habrá habido como él

en el amor y en la guerra.

Sobre la huerta y el patio

las torres de Balvanera

y aquella muerte casual

en una esquina cualquiera.

must have stepped this earth.

No one must have lived like him

in love and war.

On the orchard and the courtyard

the towers of Balvanera

and that fortuitous death

on any street corner.

The milonga is followed by “Alguien le dice al tango.” Sung confidently by Jairo, this spirited piece is a traditional tango in the style of Piazzolla’s predecessors, stating its themes forcefully and disappearing with a dramatic flourish. The silence is shattered by the manic bandoneón and scratching riffs of “El títere.” The most frenetic song on the album, its bizarre tale of a brothel marionette is interrupted by sudden stops, stuttering runs on the bass, and strings that whistle like sirens—a manifestation of the song’s parrots and cats, or perhaps the unseen puppeteer working the strings?

The next song is my personal favorite, “A don Nicanor Paredes.” A dark milonga about a vanished caudillo, the song is touched by romantic melancholy and bitter nostalgia. Woven around Jairo’s intimate voice, the score seamlessly merges a traditional milonga with Gregorian chant and chamber music. “A don Nicanor Paredes” is Piazzolla at his most sublime, effortlessly collapsing the boundaries between genres and creating something timeless, at home with either Aníbal Troilo or Richard Strauss.

Side one concludes with “Oda íntima a Buenos Aires.” Considered by Piazzolla to be the most “vocally audacious” piece on the album, it features the return of the narrator and the introduction of a chorus. Described as a “porteño ode,” the piece is unabashedly melodramatic, charged with the sentimental grandeur and nutty beauty of a spaghetti western. When the chorus enters, it’s impossible not to think of Ennio Morricone, and underscores Piazzolla’s Italian heritage as well as that of Buenos Aires itself.

The second half of Borges & Piazzolla is occupied by the multi-part suite, “El hombre de la esquina rosada,” a setting of the story “Streetcorner Man.” (Or, more properly translated, “Man on Pink Corner.”) Unfolding across seven movements, “El hombre” covers a broad range of musical territory, from traditional tango to unexpected diversions into aleatory music and serialism. The band navigates the complexities of the suite with clarity and confidence, keeping the momentum surging and bringing a sense of cohesion to its disparate pieces. A mixture of narration and song, the vocals reflect the dramatic turns of the story, from the unresolved edginess of “Rosendo y la Lujanera” to the mannered harshness of “Aparición de Real.” Like Piazzolla’s later Rough Dancer and the Cyclical Night, “El hombre de la esquina rosada” ends with a reprise of the introductory theme, suggesting the endless loop of destiny—Rosendo will always be shamed, Real will always be stabbed, and Lujanera will forever remain a prize.

Borges & Piazzolla is a delightful fusion of music and poetry delivered with flawless virtuosity and irrepressible enthusiasm. Whether you are a fan of Borges looking to explore Argentine music, or you’ve just been stabbed in a bordello, I cannot recommend this album more highly. At the risk of venturing into heresy, I believe it exceeds the original El tango in every way. More willing to embrace the inherent melodrama of its subject matter, Borges & Piazzolla feels less self-conscious than El tango. Of course, it’s impossible to discount the passage of time between the two albums. During those thirty-odd years, Piazzolla’s “neuvo tango” went from divisive controversy to universal acclaim, and an entire generation of musicians grew up with the understanding that genres were meant to be smashed. Perhaps the music of Borges & Piazzolla had to be freed from its eponymous creators to be fully appreciated, “rescued” from contemporary expectations and placed into context as vital modern music, much as Morricone’s film scores or Camarón’s nuevo flamenco masterpiece, La leyenda del tiempo. As Borges writes ironically in “¿Dónde se habrán ido?” from Para las seis cuerdas:

Nothing improves a reputation

Like confinement to a grave.

Liner Notes (1965 Polydor LP)

By Astor Piazzolla

El tango

Polydor, 1965

Before commenting on this record’s music I would like you to know what it means to me to be a collaborator of Jorge Luis Borges. The responsibility has been big, but even larger the compensation when I learned that a poet of his magnitude identified himself with all my tunes—and it will be even greater if you share that feeling.

The music for “El hombre de la esquina rosada” was composed in March, 1960, in New York City. The work came out of an idea by choreographer Ana Itelman, who adapted sentences from Borges’ short story. The score is for narrator, singer, and 12 instruments. The musical treatment ranges from the simplest tango essence to hints of dodecaphonic music.

The music for Jorge Luis Borges’ poem “El Tango” has been especially composed following and respecting its contents. This gave me the opportunity to experiment with aleatoric music in the percussion scores. The recording has been made exclusively by my quintet, which means noises you hear were made solely with their instruments. The violin produces a percussive effect by hitting the end of its handle with a ring, doing “pizzicati” with “glissé,” imitating a siren with a “glissé” on the string, imitating sandpaper with the end of the bow behind the bridge and a drum by doing “pizzicati” with the nails between two strings. The electric guitar imitates a bongo, sirens with “glissé” effects, add minor seconds and strange effects with six strings open behind the bridge. The pianist hits treble and bass notes with the palms of his hands, and with his fists on the lower notes. The bassist hits the back part of his instrument with the palm of his hand, makes “glissés” on the bass strings and hits four strings with his bow. Bandoneón imitates a bongo by hitting the box with the left annular finger. It also has, on a side, a sort of metallic güiro to be scratched with a nail. All these effects were improvised to introduce so-called aleatoric music into tango.

The milonga “Jacinto Chiclana,” the tango “Alguien le dice al tango,” and the tango-milonga “El títere” are the simplest tunes in this recording. Simple because they simply follow the spirit of Jorge Luis Borges’ poems. “Jacinto Chiclana” has the spirit of a milonga played with guitar, that is, the type of improvised milonga. “Alguien le dice al tango” can be considered, melodically and harmonically, within the 1940s style, and “El títere” could be defined as the prototype of light, joyful and “compadrón” rhythm of the turn of the century.

Due to its dramatic contents, I have composed “A don Nicanor Paredes” on an 8-bar measure of Gregorian chant and resolving the melodic part without artificial modernism—everything very simple, deeply felt and honest.

The “Oda íntima a Buenos Aires,” composed for singer, narrator, choir and orchestra, is perhaps the most audacious of all tunes for singing. Despite that, its melodic line is simple. It begins in ascending chromatic mode and ends up in descending chromatic mode.

Liner Notes (1997 Milan CD)

By Laura Escalada Piazzolla

Borges & Piazzolla: Tangoes & Milongas

Milan, 1997

The Borges-Piazzolla encounter was magic and inevitable at the time. Of that meeting this work was born, a pride and heritage to the world from two great Argentines. As chairwoman of the Astor Piazzolla Foundation, I congratulate Milan for re-issuing this beautiful alchemy in which poetry and music join for our delight. Thanks, Georgie. Thanks, Astor. Thanks, Milan.

By María Kodama

Faithful to his father’s teachings regarding the impossibility of remembering, to treasure in our memory reality as we first saw it, Borges does not believe in history. History does not exist, because it is between the distortion of facts through innumerable generations who told them and he, a poet, through words inspired by a muse, through sacred words, who will undertake the impossible—changing the past.

In “Fundación Mítica de Buenos Aires,” of his book Cuaderno San Martín (1929), he says: “men shared an imaginary past.” This will allow Borges to locate, despite history, the foundation of Buenos Aires in his barrio, Palermo. He recovers that past through memory to modify it at will. He thus tears up the fabric of a “fallacious history,” and attempts to recover the first, archetypical vision—that of myth.

Mythically founded, his city will be populated by the compadritos—men who owe deaths but are not cowards. These men from the slums, as described and sung by Borges, will make a special frieze. They will be courageous and will always respect the codes of the society in which fate made them be born. Hostile men, fearful of tenderness and feelings, they will allow themselves to be drawn by tango music—that “brothel’s reptile,” as Lugones called it.

In Borges’ memory was a nostalgia for Arolas and Greco’s tangos he had seen danced in the streets when he was a child.

Those are the tangos he will like all his life, a preference shared with that of milongas, because of their ironically cheerful rhythm.

Borges will write tangos and milongas for the pleasure of his readers. He will write them to exorcise the image of revenge, abandonment and cry of tangos and trying to make his characters become “full men.”

By Producer Envar el Kadri

In 1995, Emmanuel Chamboredon and I agreed upon producing a record to rescue a work made in 1965 by Astor Piazzolla with Edmundo Rivero and Luis Medina Castro, based on poems by Jorge Luis Borges. We thought it was necessary to give it the importance it had due to the quality of the authors and the symbolism they evoke anywhere in the world—that of Buenos Aires, cradle of tango music.

These poems by Borges are a tribute to the city and a certain lifestyle of its people, for whom “courage is better/hope is never vain,” which is being lost among the foldings of the “global village” and a conformity lacking ideals. Astor’s music is also associated to this celebration of an archetypical man “capable of not raising his voice/and (yet) gamble his life.” As Astor himself said, his music, especially composed for this work, ranges from “the simplest tango essence to aleatory music, dodecaphonic music and Gregorian chant.”

With the support of his heirs, we called upon performers who could match the bet: Daniel Binelli, who puts his talent in bandoneón and conducted the work; Jairo, who recreated the magic of these songs with his art; Lito Cruz, who incarnated Borges’ characters as if they were in front of us, and first-rate musicians who would not only read notes but made music with their souls, as Piazzolla wanted.

This juncture of art and talent, poetry and music, made producing this record—with Laura Fonzo’s sophisticated techniques and the valuable cooperation of Alejandra Kaufman—become a source of pure emotion instead of what is generally just effort and work. Surely, you will be able to discover and share that yourselves when you listen to it.

By Daniel Binelli

In the realization of this album I gave all of my heart to the memory of Astor Piazzolla and Jorge Luis Borges. Throughout the whole performance I have tried to reflect Astor Piazzolla’s intense and inimitable style. For that, I had a qualified group of Argentine musicians who contributed all their art to join me in this great project. Jairo’s singing and Lito Cruz’ voice reading poems finish up the framework for this wonderful work by Borges and Piazzolla, which was composed in the 1960’s.

Lyrics

Because the liner notes do not reprint the lyrics, I am taking the liberty of doing that here. The following are the Borges texts for the six tangos and milongas that compose the first half of both El tango and Borges & Piazzolla. Where I could find English translations, they have been included.

El tango

¿Dónde estarán? pregunta la elegía

de quienes ya no son, como si hubiera

una región en que el Ayer, pudiera

ser el Hoy, el Aún, y el Todavía.

¿Dónde estarán? (repito) el malevaje

que fundó en polvorientos callejones

de tierra o en perdidas poblaciones

la secta del cuchillo y del coraje?

¿Dónde estarán aquellos que pasaron,

dejando a la epopeya un episodio,

una fábula al tiempo, y que sin odio,

lucro o pasión de amor se acuchillaron?

Los busco en su leyenda, en la postrera

brasa que, a modo de una vaga rosa,

guarda algo de esa chusma valerosa

de Los Corrales y de Balvanera.

¿Qué oscuros callejones o qué yermo

del otro mundo habitará la dura

sombra de aquel que era una sombra oscura,

Muraña, ese cuchillo de Palermo?

¿Y ese Iberra fatal (de quien los santos

se apiaden) que en un puente de la vía,

mató a su hermano, el Ñato, que debía

más muertes que él, y así igualo los tantos?

Una mitología de puñales

lentamente se anula en el olvido;

Una canción de gesta se ha perdido

entre sórdidas noticias policiales.

Hay otra brasa, otra candente rosa

de la ceniza que los guarda enteros;

ahí están los soberbios cuchilleros

y el peso de la daga silenciosa.

Aunque la daga hostil o esa otra daga,

el tiempo, los perdieron en el fango,

hoy, más allá del tiempo y de la aciaga

muerte, esos muertos viven en el tango.

En la música están, en el cordaje

de la terca guitarra trabajosa,

que trama en la milonga venturosa

la fiesta y la inocencia del coraje.

Gira en el hueco la amarilla rueda

de caballos y leones, y oigo el eco

de esos tangos de Arolas y de Greco

que yo he visto bailar en la vereda,

en un instante que hoy emerge aislado,

sin antes ni después, contra el olvido,

y que tiene el sabor de lo perdido,

de lo perdido y lo recuperado.

En los acordes hay antiguas cosas:

el otro patio y la entrevista parra.

(Detrás de las paredes recelosas

el Sur guarda un puñal y una guitarra.)

Esa ráfaga, el tango, esa diablura,

los atareados años desafía;

hecho de polvo y tiempo, el hombre dura

menos que la liviana melodía,

que solo es tiempo. El Tango crea un turbio

pasado irreal que de algún modo es cierto,

el recuerdo imposible de haber muerto

peleando, en una esquina del suburbio.

Jacinto Chiclana

Me acuerdo, fue en Balvanera,

en una noche lejana,

que alguien dejó caer el nombre

de un tal Jacinto Chiclana.

Algo se dijo también

de una esquina y un cuchillo.

Los años no dejan ver

el entrevero y el brillo.

¡Quién sabe por qué razón

me anda buscando ese nombre!

Me gustaría saber

cómo habrá sido aquel hombre.

Alto lo veo y cabal,

con el alma comedida;

capaz de no alzar la voz

y de jugarse la vida.

(Recitado)

Nadie con paso más firme

habrá pisado la tierra.

Nadie habrá habido como él

en el amor y en la guerra.

Sobre la huerta y el patio

las torres de Balvanera

y aquella muerte casual

en una esquina cualquiera.

No veo los rasgos. Veo,

Bajo el farol amarillo,

El choque de hombres o sombras

Y esa víbora, el cuchillo.

Acaso en aquel momento

En que le entraba la herida,

Pensó que a un varón le cuadra

No demorar la partida.

Sólo Dios puede saber

la laya fiel de aquel hombre.

Señores, yo estoy cantando

lo que se cifra en el nombre.

Entre las cosas hay una

De la que no se arrepiente

Nadie en la tierra. Esa cosa

Es haber sido valiente.

Siempre el coraje es mejor.

La esperanza nunca es vana.

Vaya, pues, esta milonga

para Jacinto Chiclana.

Jacinto Chiclana

I remember, it was in Balvanera,

in a distant night,

that someone dropped the name

of someone named Jacinto Chiclana.

Something was also said

about a street corner and a knife.

The passing years don’t let us see

the brawl and the sheen.

Who knows for what reason

that name is looking for me!

I would like to know

how must have been that man.

I picture him tall and consummate,

with his obliging soul;

capable of not raising his voice

and ready to risk his life.

(Chorus)

No one with a firmer footing

must have stepped this earth.

No one must have lived like him

in love and war.

On the orchard and the courtyard

the towers of Balvanera

and that fortuitous death

on any street corner.

I do not see the characteristics. I see,

under the yellow light,

the clash of men or shadows

and that viper, the knife.

Perhaps at that moment

when the wound entered his body,

he thought that to a man it suits

not to delay the departure.

Only God can know

the faithful kind of that man

Gentlemen, I am singing

what’s centered in the name.

Among all things there is one

of which there are no regrets

from nobody on Earth. That thing

is to have been brave.

The courage is always better.

The hope is never vain.

So, then, this milonga

is for Jacinto Chicano.

Translation by Alberto Paz

Alguien le dice al tango

Tango que he visto bailar

contra un ocaso amarillo

por quienes eran capaces

de otro baile, el del cuchillo.

Tango de aquel Maldonado

con menos agua que barro,

tango silbado al pasar

desde el pescante del carro.

Despreocupado y zafado,

siempre mirabas de frente.

Tango que fuiste la dicha

de ser hombre y ser valiente.

Tango que fuiste feliz,

como yo también lo he sido,

según me cuenta el recuerdo;

el recuerdo fue el olvido.

Desde ese ayer, ¡cuántas cosas

a los dos nos han pasado!

Las partidas y el pesar

de amar y no ser amado.

Yo habré muerto y seguirás

orillando nuestra vida.

Buenos Aires no te olvida,

tango que fuiste y serás.

Someone Speaks of Tango

Tango that I have seen danced

against a yellow sunset

for those were capable

of other dance, of that of the knife.

Tango of that Maldonado

with less water than mud,

tango whistled to pass

from the driver’s seat of a car.

Carefree and cheeky,

always you should look straight ahead.

Tango that became to you happiness

to be a man, to be courageous.

Tango that you went to to be happy.

as I also have done.

according to what the memory tells me;

the memory that was the oblivion.

After this yesterday, how many

things have happened to the two of us!

The fissures and sorrow

of loving and not being loved.

I would be dead and I would continue

Passing over our life.

Buenos Aires I don’t forget you.

Tango that went and will be.

Translation by Marissa Colón-Margolies

El títere

A un compadrito le canto

Que era el patrón y el ornato

De las casas menos santas

Del barrio de triunvirato.

Atildado en el vestir,

Medio mandón en el trato;

Negro el chambergo y la ropa,

Negro el charol del zapato.

Como luz para el manejo.

Le marcaba un garabato

En la cara al más garifo,

De un solo brinco, a lo gato.

El hombre, según se sabe,

Tiene firmado un contrato

Con la muerte. en cada esquina

Lo anda acechando el mal rato.

Ni la cuartiada ni el grito

Lo salvan al candidato.

La muerte sabe, señores,

Llegar con sumo recato.

Un balazo lo paró|

En thames y triunvirato.

Se mudó a un barrio vecino:

El de la quinta del ñato.

Bailarín y jugador,

No sé si chino o mulato.

Lo mimaba el conventillo;

Que hoy se llama inquilinato.

A las pardas zaguaneras

No les resultaba ingrato

El amor de ese valiente

Que les dio tan buenos ratos.

A don Nicandor Paredes

Venga un rasgueo y ahora,

Con el permiso de ustedes,

Le estoy cantando, señores,

A don Nicanor Paredes.

No lo vi rígido y muerto.

Ni siquiera lo vi enfermo.

Lo veo con paso firme

Pisar su feudo, Palermo.

El bigote un poco gris,

Pero en los ojos el brillo,

Y cerca del corazón

El bultito del cuchillo.

El cuchillo de esa muerte

De la que no le gustaba

Hablar; alguna desgracia

De cuadreras o de taba.

De atrio, más bien. Fue caudillo,

Si no me marra la cuenta,

Allá por los tiempos bravos

Del ochocientos noventa.

Si entre la gente de faca

se armaba algún entrevero

él lo paraba de golpe,

de un grito o con el talero.

Ahora está muerto y con él

cuánta memoria se apaga

de aquel Palermo perdido

del baldío y de la daga.

Ahora está muerto y me digo:

¿Qué hará usted, don Nicanor,

en un cielo sin caballos,

sin vino, retruco y flor?

Of Don Nicanor Paredes

Let the chords commence and now,

Most humbly, I will present

My song to Don Nicanor Paredes,

Gentlemen, with your assent.

I did not see him stiff and dead

Not even withering and gaunt

I see him walking with firm tread

Across Palermo, this first haunt.

The mustache graying at the ends,

But in his eyes a youthful vigor,

And, kept forever near the heart,

The little bundle of the dagger.

The dagger of that mysterious death

he carried with him, some disgrace

Of which he did not care to speak;

A game of bones or luckless race.

Of the courtyard, shall we say,

He was, or so the story goes,

A local boss there in the wild

Nineteenth century’s mortal throes.

When among those reckless spirits

Some skirmish suddenly broke out

He stopped it with a single blow,

With a horsewhip or a shout.

Now he is dead, and with his death

Such memories have been put to rest

Of lost Palermo, its sad lots,

And of the dagger at his breast.

Now he is dead and I ask aloud:

What will you do, Don Nicanor,

In a heaven where no horses run,

Where there is no debt, no stake, no score?

Translation by Eric McHenry

Additional Information

Additional Information

Borges reading “El tango”

A recording of Borges reading his poem, with Spanish text.

“El títere”

This stuttering version of “El títere” by Silvana Deluigi and Duo Mosalini Senso may even be crazier than Binelli’s.

Reconsidering the Collaboration Between Piazzolla and Borges

This paper by John Turci-Escobar explores the oft-contentious “collaboration” that produced El Tango. It appeared in Variaciones Borges No. 31, and is available from the Borges Center. [PDF]

Tangos al bardo: Piazzolla y Borges

This tango blog discusses El Tango. [Spanish]

Astor Piazzolla’s Borges-Related Works

Astor Piazzolla Main Page

Return to the Garden of Forking Path’s Astor Piazzolla profile.

El tango (1965)

Piazzolla set some of Borges’ poems and milongas to music on the album El tango.

María de Buenos Aires (1968)

Piazzolla’s great “tango operita,” this surreal work was a collaboration with Uruguayan poet Horacio Ferrer. Although not directly related to Borges, its themes are often reminiscent of Borges’ early work.

A intrusa (1979)

Piazzolla’s score to A intrusa, a homoerotic Brazilian movie directed by Carlos Hugo Christensen and loosely based on Borges’ story “The Intruder.”

The Rough Dancer and the Cyclical Night (1987)

A cycle of fourteen pieces inspired by Borges’ poetry, this work was commissioned for the Hispanic American Arts Center’s production of Tango Apasionado.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 7 August 2024

Borges Music Page: Borges and Music

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com