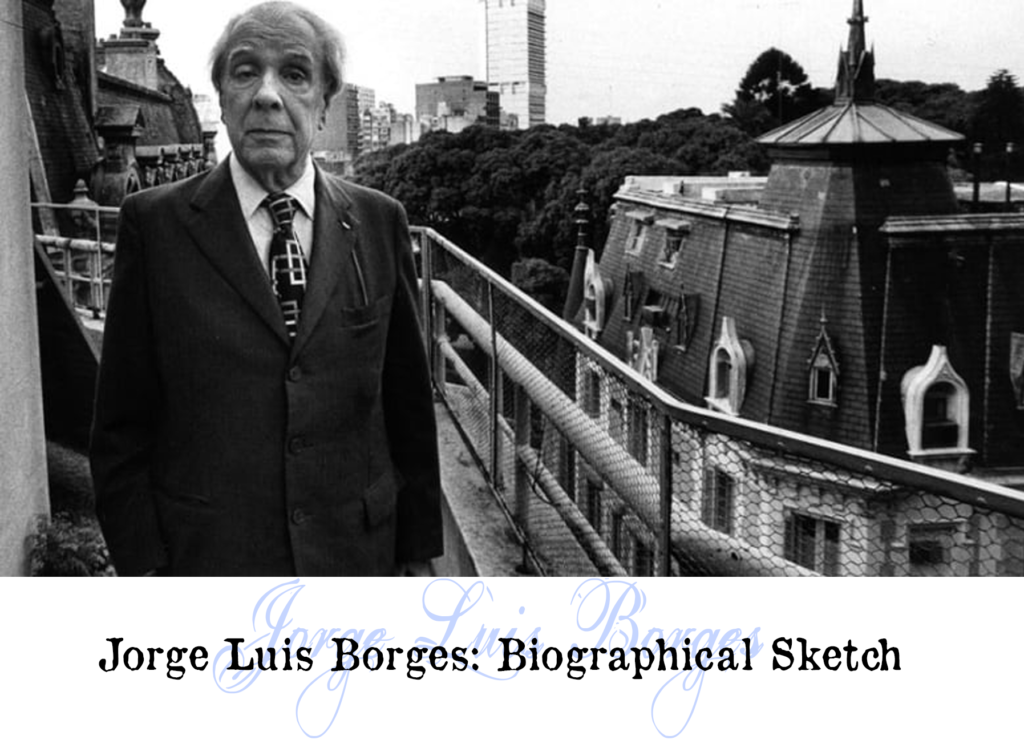

Borges Biography

- At July 22, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

2

2

“I, unfortunately, am Borges.”

Libraries and Garden Labyrinths: A Dream of Childhood

For myth is at the beginning of literature, and also at its end.

—Parable of Cervantes and Don Quixote

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires on 24 August 1899. Shortly after his birth, his family relocated to Calle Serrano 2135/47 in Palermo, a suburb on the northeast outskirts of Buenos Aires along the bank of the Río de la Plata. With its roots in the Italian immigrant community, Palermo was named in honor of San Benito de Palermo, or “Saint Benedict the Moor,” the Sicilian saint and namesake of the local Franciscan abbey.

Borges’ home at 2135 Calle Serrano, now renamed Calle Jorge Luis Borges. Note the plaque.

Today, Palermo is a trendy neighborhood known for its high cost of living and myriad boutiques; but at the turn of the century, it was considered a vaguely seedy, lower-class barrio with a reputation for discordant politics and knife-wielding compadritos. Once the site of the dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas’ pleasure gardens, the barrio’s rejuvenation began in the 1870s with the creation of the Zoological Gardens, followed by the Parque Tres de Febrero, the Plaza Italia, the Palermo Hippodrome, and the Botanical Gardens. These attractions drew more visitors and sightseers, and soon Palermo’s original inhabitants found themselves being displaced by a growing number of middle-class residents. By the time Borges entered his childhood, gentrification was well underway, and the neighborhood had begun to lose some of its colorful character. Still, Palermo enchanted young Borges with its legacy of cabarets and brothels, its tales of wanton women and violent men, desperadoes who danced the tango and enacted vengeance at the point of a knife. Borges absorbed the barrio’s outlaw heritage with the intensity of a boyish intellectual attracted to the dangerous and misbegotten, and its influence is evident in much of his earliest work.

While Palermo might have inflamed the imagination of the young Borges, his middle-class parents felt distinctly out of place. His father, Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, was a lawyer and a psychology teacher whose political beliefs were predicated on a Spencerian fondness for anarchy. Plagued by chronic eye problems, he distracted himself by writing historical fiction in the criollismo style of literary regionalism. His mother, Leonor Acevedo Suárez de Borges, was a proud woman descended from a lineage of soldiers; her own mother Leonor Suárez de Acevedo had furnished their home with family artifacts such as swords, uniforms, and noble portraits of freedom fighters.

Borges’ parents spoke and read English, and his paternal grandfather, Colonel Francisco Borges Lafinir, had married an Englishwoman from Staffordshire named Francis Anne Haslam. Colonel Borges was shot and killed in 1874, but Grandmother Fanny lived with her son, and often held her grandson “Georgie” spellbound with stories from the wild frontier days. The mature Borges frequently remarked that his grandmother’s dry English wit was the origin of his concise style. (In an interesting parallel, Gabriel García Márquez attributed his own deadpan fabulism to his storytelling grandmother in Colombia.) Borges’ grandmother read him English magazines, and she hired an Englishwoman named Mrs. Tink to be his nanny. Borges later claimed that his household was so fluidly bilingual that for most of his childhood, he assumed English and Spanish were the same language!

Jorge Guillermo and Leonor Acevedo

Borges was terribly fond of both his parents. His father taught him philosophy, once using a chessboard to explain Zeno’s paradox, and his mother, who lived to see 99, was a strong woman who eventually traveled the world with her famous son. Borges’ younger sister Norah, his junior by two years, was his closest childhood friend. They invented imaginary playmates named “Quilos” and “The Windmill,” acted out scenes from books, and happily roamed the twin labyrinths of library and garden, two settings that Borges would later mythologize endlessly in his writing. When the weather grew warm, the Borges family retired to their summerhouse in Adrogué, a nearby town where the reasonably well-to-do could relax in a European setting complete with tennis courts, English-style schools, and garden mazes scented with “the ubiquitous smell of eucalyptus trees.” Young Georgie was especially fond of the zoo, and spent countless hours gazing at the animals, particularly the tigers—his favorites. As he remarked toward the end of his life: “I used to stop for a long time in front of the tiger’s cage to see him pacing back and forth. I liked his natural beauty, his black stripes and his golden stripes. And now that I am blind, one single color remains for me, and it is precisely the color of the tiger, the color yellow.” In fact, a common punishment meted out to Georgie was to deny him trips to see his beloved tigers!

Despite his fondness for gaucho stories, his games with his sister, and his relaxing summers in Adrogué, Borges later remarked that he felt alienated as a child. The son of a middle-class lawyer living in Palermo, he was a bookish and nearsighted boy who tended to hide indoors. And yet in the manner common to children everywhere, in his imagination Borges fancied himself to be an active part of the local scenery. He eventually established a friendship with a local poet, his neighbor Evaristo Carriego, a reckless man who represented much of the “sentimental machismo” of Argentine tradition and became one of Borges’ early idols. It wasn’t until much later, returning to Buenos Aires after spending seven years in Europe, that Borges admitted to himself that “for years I believed I had grown up in a suburb of risky streets and visible sunsets. The truth is I grew up in a garden, behind lanceolate railings, and in a library of unlimited English books.” He later wrote a small book on the poet Carriego in which Borges reconciled the fact that his younger self was no denizen of the streets, but rather a quiet intellectual. The compadritos, gauchos, and knife fights that haunt Borges’ work are not the product of lived experiences, but fantastic projections steeped in romance and mythology—which is perhaps why they are so enduring.

Evaristo Carriego

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Juvenilia

Of course, like all young men, I tried to be as unhappy as I could—a kind of Hamlet and Raskolnikov rolled into one.

—Autobiographical Essay 1970

Jorge Luis Borges was always expected to be a writer. His father Jorge Guillermo had made several attempts, and as his blindness increased over the years, it became a tacit understanding that his son would carry on the tradition. Jorge Luis started writing at the age of six, mostly fanciful stories inspired by Cervantes. When he was nine, he translated Oscar Wilde’s “The Happy Prince” into Spanish, an effort which appeared in the local newspaper El País. Since it was signed “Jorge Borges,” everyone assumed it was his father’s work. After a few visits to La Pampa, where his maternal cousins owned a ranch on the Uruguay River, Borges attempted to write gaucho poems, but quickly confessed they were a failure. But still the countryside exerted its attraction, and in addition to learning how to swim, Borges absorbed numerous impressions that would find more fulfilling literary expression later in his career.

In 1908 Borges began to attend school—his father’s anarchist sentiments had kept him out until now—but he was taught little but Argentine nationalism. He was also dismayed by the comparatively low moral and intellectual character of his fellow classmates. Adopting an English style of dress in a predominantly anti-English school, wearing thick glasses, and already possessing a superior education, Borges was an easy target for local bullies. Animated by a quixotic sense of ancestral honor, Georgie refused to back down from a fight; but unfortunately his vigor could not match his pride, and he ended up well-acquainted with defeat. Indeed, Borges came to loathe primary school, even though he excelled at it academically. In 1913, Borges was accepted to the Colegio Nacional Manuel Belgrano. That same year he published his first story in the school newspaper. Entitled, “El rey de la selva,” or “The King of the Jungle,” Borges submitted it under the name “Nemo.”

Relief from his tormentors came in 1914, when Borges’ life experienced a drastic upheaval. Forced into early retirement by his failing eyesight, his father packed up the entire family and moved to Europe, spending a few weeks in Paris before arriving in Geneva to consult a Swiss eye specialist.

Discovery In Europe: An Adolescent Awakening

Of all the cities on this planet, of all the diverse and intimate places which a man seeks out and merits in the course of his voyages, Geneva strikes me as the most propitious for happiness. Beginning in 1914, I owe it the revelation of French, of Latin, of German, of Expressionism, of Schopenhauer, of the doctrine of Buddha, of Taoism, of Conrad, of Lafcadio Hearn and the nostalgia of Buenos Aires. Also: the revelation of love, of friendship, of humiliation and of the temptation to suicide.

—“Geneva,” 1984

Their timing was hardly ideal, and the outbreak of the First World War stranded the Borges family in Geneva for the next four years. The children were enrolled at Collège Calvin, where they learned to speak Latin, German, and French—a language at which Norah became more proficient than her brother. Fortunately, the students were of a higher caliber than those who attended the state-run school in Buenos Aires, and Borges even made a few friends. In fact, his new friends convinced the headmaster to promote him despite his poor mastery of French!

Borges’ years at Collège Calvin were crucial to his development as a writer, and each month brought a fresh discovery. Introduced to the Symbolists by a pair of Polish friends named Maurice Abramowicz and Simon Jichlinski, Borges devoured the works of Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, and Stéphane Mallarmé, finding in abstract literature an exciting new way of understanding and representing the world. He fell in love with Walt Whitman, whom Borges believed to be the culmination of all the subtle aims of poetry; and he established a lifelong obsession with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. From Thomas Carlyle, Borges discovered something as important as Symbolism or free verse: often inventing the idea of a book is just as effective as writing it. They were an incredibly productive four years, and while so many of Europe’s youth were dying in muddy fields and trenches, the young Argentine lost himself in the promise of her enlightened past. Borges even managed to visit Northern Italy, where he recited gaucho poetry to the empty amphitheaters of Verona.

Borges and Norah in Geneva

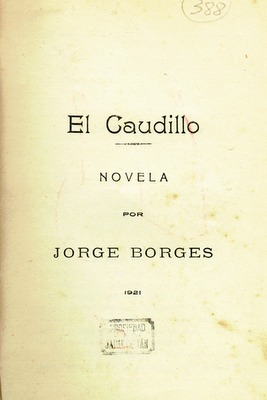

In 1919 Borges’ maternal grandmother died. The War being over, the Borges family departed Geneva for Lugano. Soon relocating to Spain, they jumped around frequently, moving from Barcelona to Majorca, then to Seville and finally Madrid. In possession of a degree and facing the hopeful expectations of a postwar landscape, Borges decided it was time to become a serious writer. After a few abortive attempts in English and French, he accepted that Spanish was to be his literary language. He began helping his father write an historical novella set during the time of Juan Manuel de Rosas. Named El Caudillo, the novella was published in Majorca in 1921, and combines Latin American criollismo with a sharp sense of social critique. El Caudillo is also known for its ambiguous sense of parody; and many have wondered whether the father influenced the son, or the other way around! Borges had his own story rejected by a magazine in Madrid, but during the winter in Seville, one of his poems finally found its way to print.

After a few unsuccessful attempts to join various literary circles, in Madrid the young writer found inspiration and a mentor in the Andalusian poet Rafael Cansinos Asséns. Under his influence, in 1920 Borges associated himself with a new circle known as the ultraístas. A group of idealists that met every Saturday night at the Café Colonial, the ultraists “admired American jazz, and were more interested in being Europeans than Spaniards.” All night long they would bandy ideas back and forth, engaged in sparkling literary conversation that fueled the fires of Borges’ imagination. It was among this circle that Borges realized he needn’t be tied down to any one tradition, particularly a national one, or even his father’s realism. He wrote two books of essays and poems, praising among other things pacifism, anarchy, the Russian Revolution, and freethinking in general. Borges quickly became embarrassed by his efforts, considering them the product of a youthful infatuation. Unfortunately for would-be collectors of Borges juvenilia, he destroyed both books before leaving Spain in 1921.

Rafael Cansinos Asséns

Fervor de Buenos Aires: The Roaring Twenties

Forgetful of the place of my birth, I struggled to be really Argentine.

—New prologue to “Luna de enfrente,” 1969

After seven years in Europe, the Borges family returned to Buenos Aires in March 1921. The city, having experienced an explosion of growth during their absence, was thriving; and Borges discovered that he’d come home to a wealth of opportunities. He quickly fell under the influence of his father’s old friend, the poet Macedonio Fernández. A dynamic and witty conversationalist, Fernández was delighted to discuss Schopenhauer, Berkeley, and Hume, and valued his young friend’s contributions even as he enjoyed spurring him to contradictions. Fern ández’s philosophical ideas were complex and his writing style eccentric, and he urged Borges to approach everything with a healthy amount of skepticism.

Macedonio Fernández

Similar to Rafael Cansinos Asséns in Madrid, Macedonio Fernández presided over a Saturday night literary circle. Invigorated by his European experiences and energized by a new-found enthusiasm for Argentina, Borges threw himself into the cultural life of Buenos Aires with the fervor of a young artist catching a rising wave. He wrote poems praising the local color, and co-founded a literary magazine named Prisma dedicated to ultraist principles. As described by historian John King, Prisma “railed against the psychological novel, lengthy poems, tired symbolism, and established forms of versification, and proposed instead innovative verse based on the power of metaphor, free from superfluous adjectives and literary ornamentation.” The magazine was printed as a large broadsheet with illustrations by Norah Borges. Citizens of Buenos Aires would occasionally wake up to find new issues plastered over the walls of the city, exploding with poems and manifestoes.

Borges began having his work appear in Nosotros, a traditional magazine known to temper its literary conservatism with occasional surveys of the youthful avant-garde. He published an explanation of ultraísmo and a few minor pieces for Nosotros, but Borges and his compatriots realized the avant-garde needed its own voice. In 1922, Jorge Luis Borges, Ricardo Güiraldes, Brendán Caraffa, and Pablo Rojas founded Proa, or “Prow.” A freely-circulated triptych illustrated by Norah, the magazine lasted only three issues.

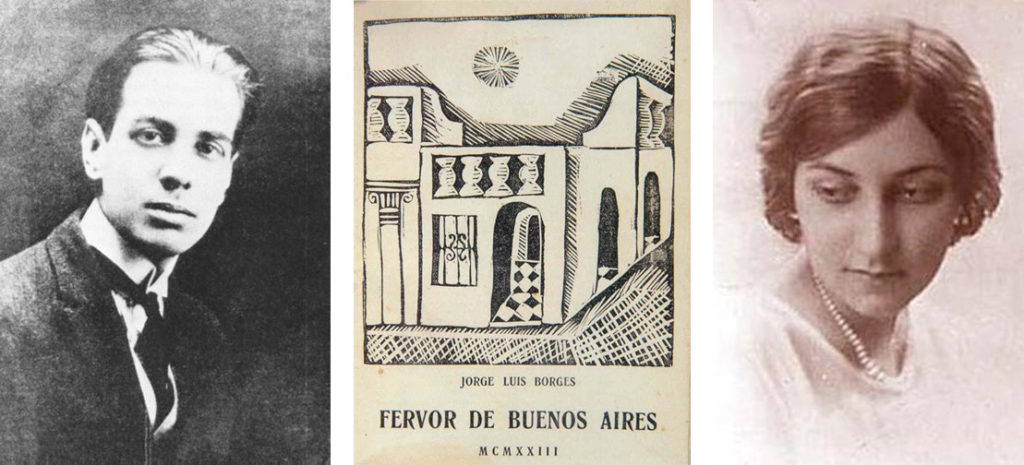

In 1923 Borges issued his first collection of original poems. Entitled Fervor de Buenos Aires, the sixty-four page book was financed by his father. Hastily printed, the cover boasted another Norah woodcut. With little regard for profit, nearly every one of the three hundred copies were distributed freely—and often surreptitiously, such copies quietly slipped into the pockets of editor’s overcoats!

Borges in 1921, Fervor de Buenos Aires, Norah Borges

In 1923 the family traveled to Switzerland so his father could continue his eye treatments. Returning to Spain, Borges was disappointed to find that the ultraist movement had petered out; but he nevertheless managed to publish a few poems, and a favorable review of Fervor de Buenos Aires appeared in a Spanish magazine named Revista de Occidente. When the family returned to Argentina next year, Borges discovered that his guerrilla tactics had paid off. In his absence, Jorge Luis Borges had developed a reputation as a budding poet!

The years from 1924 to 1933 were exciting and prolific for Borges. In 1924 he relaunched Proa, now expanded to seventy pages and including interior artwork and advertisements. He began seeing more of his work in print, particularly in Nosotros and Inicial, and was a contributor to an exciting new magazine called Martín Fierro. Known for its eclectic and iconoclastic ethos, Martín Fierro was devoted to avant-garde poetry and art, satirical pastiche, and irreverent humor, and counted Macedonio Fernández, Oliverio Girondo, and Xul Solar as frequent contributors.

Ironically, Borges’ involvement with Martín Fierro took an unexpected turn when the editors decided to invent a literary feud to help drum up sales. The publicity stunt involved two groups of writers: the aristocratic and intellectual “Florida” group, who cultivated an air of continental sophistication; and the streetwise “Boedo” group, steeped in leftist politics and gaucho lore. Both groups took their names from the locations of their favorite meeting spots: the Confitéria Richmond on the upscale and bustling Florida Street, and the Café El Japonés in the Boedo, a working-class barrio known for its association with the tango.

Florida Street is on the left; the right shows Café El japonés in the Boedo.

Because of his European attachments and his reputation as an intellectual, Borges was assigned to the “Florida” group, a decision which he unsuccessfully appealed. Borges wanted to write vulgar literature filled with danger and local color, not urbane works of “art for art’s sake!” Disappointed, he spent the next few years trying to divorce himself from his effete “Florida” image. To the considerable dismay of his mother, Borges began spending his evenings in less reputable parts of the city, attempting to revive the romantic ghosts of his Palermo childhood through “late afternoons, drab outskirts, and unhappiness.” He conversed with hoodlums, learned to dance the tango, and studiously absorbed lunfardo, the local Italian-inflected argot. The result was a series of poems decidedly more “Boedo” than “Florida,” collected in Luna de enfrente (1925) and Cuaderno San Martín (1929).

Borges published three collections of essays during the twenties: Inquisiciones (1925), El tamaño de mi esperanza (1926), and El idioma de los argentinos (1928). This third, “The Language of the Argentines,” netted him the Second Municipal Prize in 1929. (One of the things Borges bought with the 3000 pesos prize money was the complete set of Encyclopaedia Britannica, a purchase that would serve him well over the years!) In 1930, Borges wrote a small book about his boyhood hero, the poet Evaristo Carriego, who had died of tuberculosis in 1912. Containing more reminiscences of a vanished Buenos Aires than actual biography, Evaristo Carriego met with less success than his poetry. Borges revised it twenty-five years later, adding a preface acknowledging that he was always more Florida that Boedo after all.

Later in life, Borges would downplay his years as a young poet, accusing himself of being overly derivative. He claimed that his pieces were so drenched in local color that “the locals could hardly understand it.” His embarrassment was such that he was actually known to buy up any copies he found of these original works and burn them. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Borges made peace with his younger self, revising his “at times agreeable to me and at other times quite unsettling” collections by moderating “baroque excesses,” polishing “rough spots,” and eliminating “sentimentality and haziness.”

Year’s End: Disillusionment and Disappointment

To fall in love is to create a religion that has a fallible god.

—The Meeting In a Dream, 1952

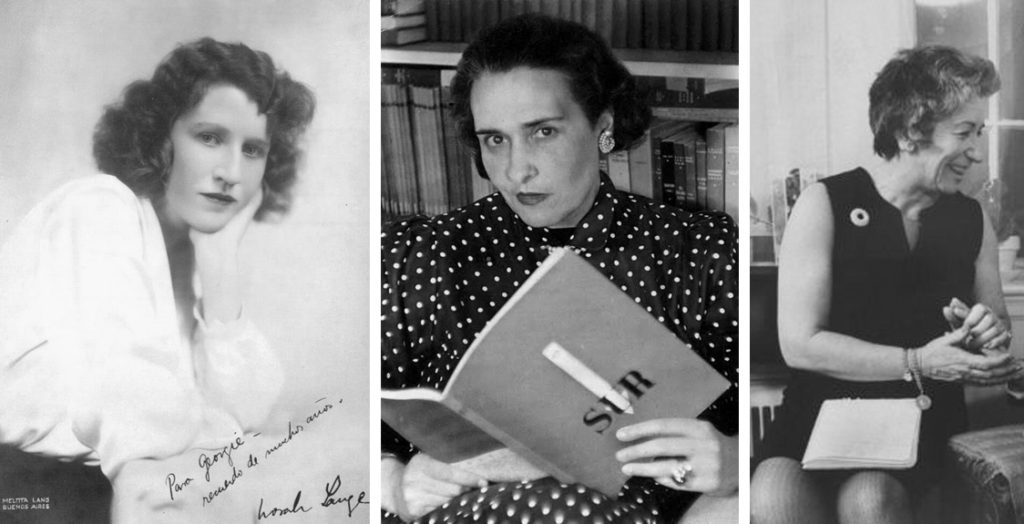

Borges’ twenties were also marked by his relationships with three notable women: Norah Lange, Victoria Ocampo, and Elsa Astete. Norah Lange was an energetic redhead of Scandinavian extraction and a writer in the Florida group. A darling of the Buenos Aires avant-garde, Lange hosted weekend literary soirees that enraptured Borges and his circle. Although Borges was quite fond of Norah, she preferred the affections of a literary rival, a well-to-do extrovert named Oliverio Girondo. Over the course of several painful years, Borges ineffectually pressed his suit through poems, letters, and dedications; rewarded only with a broken heart and a somewhat less optimistic view of the world. Victoria Ocampo, whom he met through his family in 1925, was a writer and translator. A very capable and headstrong editor, she promoted Borges’s writing through Sur, an influential literary magazine she founded in 1930. Elsa Astete was a 20-year old beauty that Borges met in 1928 on a double-date with his friend and her older sister. After a brief romance with Borges, Astete suddenly married another man; but some forty years later, the two would reunite, and Elsa Astete Millán would become Borges first wife.

From left to right: Norah Lange, Victoria Ocampo, and Elsa Astete (photographed later in life).

During this time Borges also developed a controversial political attachment. In an interesting and fractious break with family tradition, he supported the campaign of former president Hipólito Yrigoyen, a figure whom Borges compared favorably to an old family enemy, the eighteenth-century dictator Juan Manuel Rosas. Yrigoyen had previously served as president from 1916 to 1922 but, as the National Constitution barred direct re-election, Yrigoyen was forced to bide his time, pulling strings from behind the scenes. In 1928 Borges featured prominently in the Committee of Young Intellectuals, a group dedicated to Yrigoyen’s re-election. Unfortunately, Borges fared no better in politics than romance, and disillusionment was the fruit of this infatuation as well. Hipólito Yrigoyen won the election with more than 60% of the votes; and to the disappointment of many of his younger supporters, he proved to be an out-of-touch and generally ineffective ruler. Borges’ dismay only deepened when Yrigoyen was overthrown by a military junta, which turned out to be the first of many more repressive regimes. Like many Argentines of his generation, Borges acquired a deep disgust for politics that lasted his entire life.

Sadly, the nearsightedness Borges saw in the world of politics was giving way to a more physical myopia. The blindness that had now completely consumed his father’s vision had finally turned upon the son. In 1927 Borges underwent an operation for cataracts; it would be the first of eight such operations. None would succeed, and by the end of his life, Borges would be completely blind.

Transformations: The Darkening Thirties

Let heaven exist, though my own place may be in hell. Let me be tortured and battered and annihilated, but let there be one instant, one creature, wherein thy enormous Library may find its justification.

—The Library of Babel

The thirties saw Borges’ writing take exciting new directions in both style and substance. In 1932 Borges published another collection of essays, Discusión. Many revolved around his newest obsession, the magical world of cinema. That same year he met the young writer Adolfo Bioy Casares during one of Victoria Ocampo’s soirees. A champion of the avant-garde and an enthusiast of the French Symbolists, Bioy Casares was only seventeen years old, but the two writers became fast friends, and were even reprimanded by their hostess for monopolizing each other’s attention! Borges’ work began to appear in the magazine Megáfono, which brought him increased publicity when they hosted a round table discussion about his writing in 1933.

Borges’ first short story was called “Hombre de la esquina rosada,” generally known in English as “Streetcorner Man.” Displaying a gritty realism and sporting an interesting twist at the end, the story was inspired by the death of a local compadrito. Published in the newspaper Crítica, Borges was sufficiently uncertain about his effort that it appeared under the pseudonym “Francisco Bustos,” the name of one of his ancestors.

He needn’t have worried. The story was a tremendous success; but Borges had no intention to become a writer of populist melodrama. In 1933 he began a series of sketches he called Historia universal de la infamia, or “A Universal History of Infamy.” Published in Crítica between 1933 and 1934, these stories borrowed characters and ideas from other works and “re-invented” them. Each sketch was imbued with a surreal sense of authenticity, a fusion of fact and fiction reported with deadpan objectivity. This seamless combination of history, mythology, and parody felt entirely original, and announced the arrival of an exciting new voice. Many Latin America writers have cited Historia universal de la infamia as a personal inspiration, and it’s widely seen as a precursor to so-called “magical realism.”Continuing in this vein, in 1935 Borges wrote “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim.” A short story masquerading as a review of a fictional novel, it’s considered the prototype of the “Borgesian” style that would come to fruition in Ficciones. In 1936 he published another collection of essays, Historia de la eternidad, or “A History of Eternity.” Borges also partnered with Adolfo Bioy Casares to found an avant-garde literary magazine named Destiempo, or “Out of Time.” Although the project was short-lived, it was the beginning of a creative partnership that would last over forty years.

Although Borges was gaining more recognition, the thirties were not a kind decade. Argentina shared the world’s economic misfortunes, and Borges’ ailing father had become completely dependent upon his mother. Borges needed a steady source of income, and in 1937 Bioy Casares’ father helped Borges secure a position as First Assistant at the Miguel Cané branch of the Municipal Library. His work involved classifying and cataloging the library’s holdings. It was a disappointingly simple job requiring a minimum of effort and producing little mental stimulation. Borges was even reprimanded for working too quickly! His colleagues were more interested in soccer, horse racing, and gossiping about girls than the books they were handling, and to add insult to injury, his superior once pointed out that Jorge Luis Borges “shared a name” with a writer they were indexing! Usually, Borges finished his appointed tasks in the morning and spent the rest of his day in the basement, reading classics and translating English and American novels. (Borges was the first to translate Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner into Spanish.) He remained in the Miguel Cané library for nine years; a decade of “solid unhappiness” leading a “menial and dismal existence.”

The Miguel Cané Library today, now housing a Borges museum!

Visions from the Basement: Mid-life Rebirth

The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverishing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few minutes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a resume, a commentary … More reasonable, more inept, more indolent, I have preferred to write notes upon imaginary books.

—Prologue to The Garden of Forking Paths, 10 November 1941

Jorge Guillermo Borges died on 14 February 1938. On Christmas Eve of that year, Borges experienced an accident that resulted in a near-fatal illness. While running up a stairway, he grazed a freshly-painted casement with his forehead. The wound became infected, and Borges spent a week confined to bed wracked by fever and hallucinations. He was taken to a hospital for an operation and developed septicemia. For a month, Borges hovered between life and death.

After his recovery, Borges was afraid that hallucination and disease might have damaged his brain, perhaps even burned away his creative powers. In a nervous attempt to test his faculties, Borges penned a new story, an attempt to create something unique. The result was “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” the tale of a man who rewrites Cervantes’ classic novel verbatim, yet creates an entirely new masterpiece. That was followed by “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” a metaphysical tour de force about an imaginary world slowly supplanting our own. Published in Victoria Ocampo’s Sur, both stories were well received, and Borges began to suspect that his experience may have actually enriched his imagination. He would later fictionalize his illness and subsequent recovery in the story, “The South.”

Delighted by this surge in creativity, Borges began writing stories in the basement of the library, planting the seeds of modern literature while his colleagues played the ponies upstairs. These new stories ingeniously mixed fact and fiction, history and philosophy, science and religion, and were filled with literary allusions and clever wordplay. Many of the stories concealed pointed barbs in their metaphysical discursions; “The Lottery In Babylon” portrayed a Kafkaesque world of invisible and unappeasable forces, while “The Library of Babel” served as an allegorical nightmare of his thankless job.

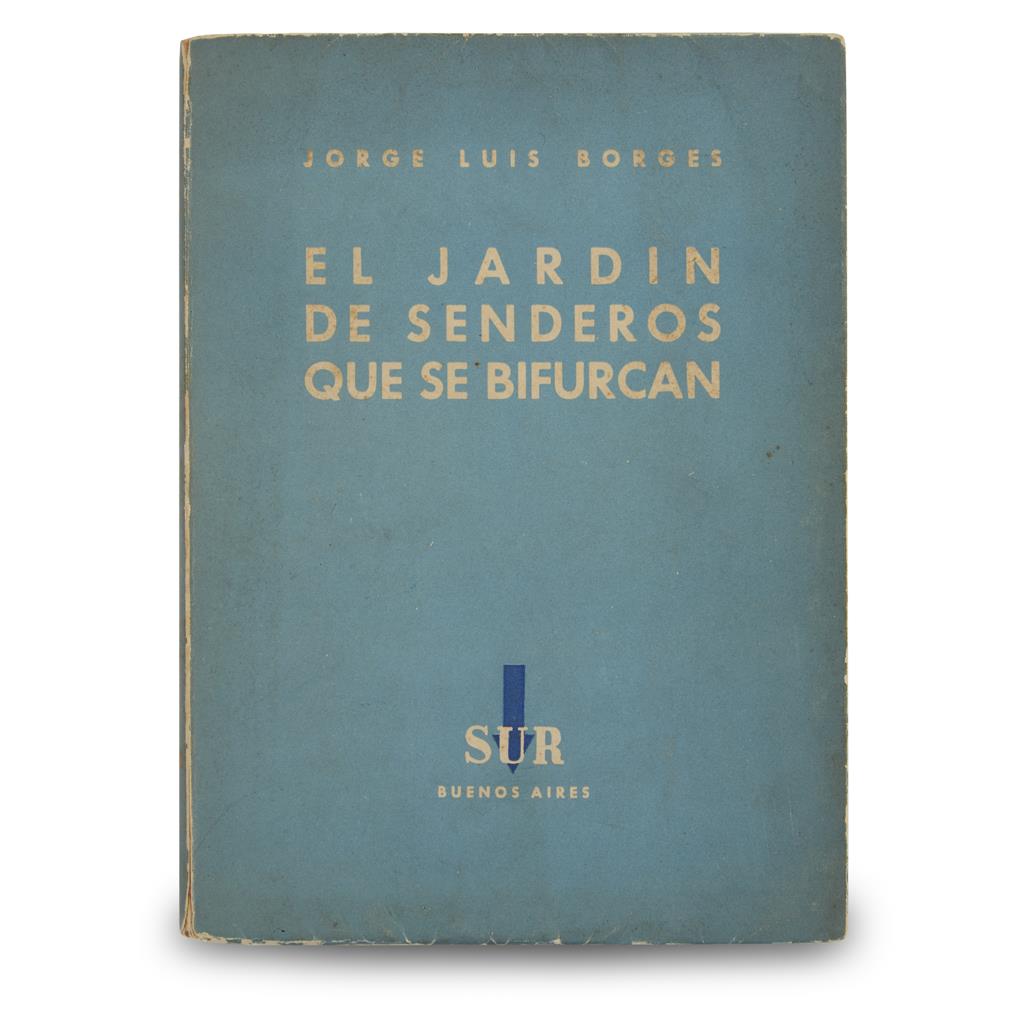

In 1941, Borges published El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan, or “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a collection of seven post-delirium stories plus “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim.” This was followed by nine additional stories collected under the title Artifices. In 1944, El jardín and Artifices were bundled together as Ficciones. A cornerstone of postmodern literature, Ficciones remains Borges’ most famous and influential work. It is virtually unclassifiable, and combines elements of traditional literature, weird fiction, mystery, historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, metaphysics, and horror. In 1942 Borges teamed up with his friend Adolfo Bioy Casares to write a series of satirical detective stories under the joint pseudonym “Bustos Domecq.” They were collected in 1942 as Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi, or “Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi.” Soon Borges’ stories were translated into French by Nestor Ibarra and Roger Callois, and he found himself being discussed alongside such writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Franz Kafka.

In addition to his fiction, Borges began writing political articles again. Appearing in El Hogar, these pieces avoided a particular political position, but broadly criticized the alarming trends of the period, including anti-Semitism, Nazism, and Argentina’s steady decline into fascism. In Argentina at least, Borges gained wider recognition for these articles than for his brilliant stories—a fact that caused problems when the fascists finally came into power. In 1946 Juan Perón was elected president, and Borges was “promoted” to Inspector of Poultry and Rabbits in the Public Markets. He resigned immediately, remarking that “dictatorships foment subservience, dictatorships foment cruelty; even more abominable is the fact that they foment stupidity. To fight against those sad monotonies is one of the many duties of writers.”

God’s Splendid Irony: The Fifties

I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of library.

—Poema de los Dones

Fortunately for Borges, losing his job proved to be a blessing in disguise. Soon after departing the library, he found himself in demand as a lecturer specializing in American and English literature. He travelled across Argentina and Uruguay, giving talks on subjects that ranged from Blake to Buddhism. He was paid handsomely, and for the first time in a while, Borges was happy—although he could not conceal his pain over his country’s embrace of fascism. The Perón regime, while coming short of detaining him outright, made generous attempts to complicate the lives of his family and friends. After taking part in a protest in 1948, Borges’ mother and sister were arrested; his mother was confined to her home, but Norah was thrown in a jail reserved for prostitutes. (When given the opportunity to be set free—if she wrote a letter of apology to Evita Perón—Norah elected to remain in jail.) Borges could rarely give a lecture without a police informer attending in the audience. Characteristic of Borges, he came to know the man usually assigned to cover him, and expressed some sympathies with the bored agent, who considered Borges to be a fine enough fellow, but one needed to earn a paycheck after all!

Still, the work continued. In 1949 his second major collection of short stories appeared, El Aleph. It is perhaps notable that the title story is about a disillusioned man who denies his enemy the opportunity to experience the entire universe. In 1950 Borges was elected President of the Sociedad Argentina de Escritores (The Argentine Writer’s Society). The SADE had strong anti-Peronista affiliations, and was under constant scrutiny. Meetings eventually fell into a typical pattern. The writers would airily discuss arcane details of literature and philosophy until the beleaguered police agents fell asleep or departed is disgust; after which the actual political discussions could take place. Despite their precautions, SADE was eventually shuttered by the regime. In 1952 Borges published his most famous collection of essays, Otras Inquisiciones, or “Other Inquisitions.”

Borges in 1951

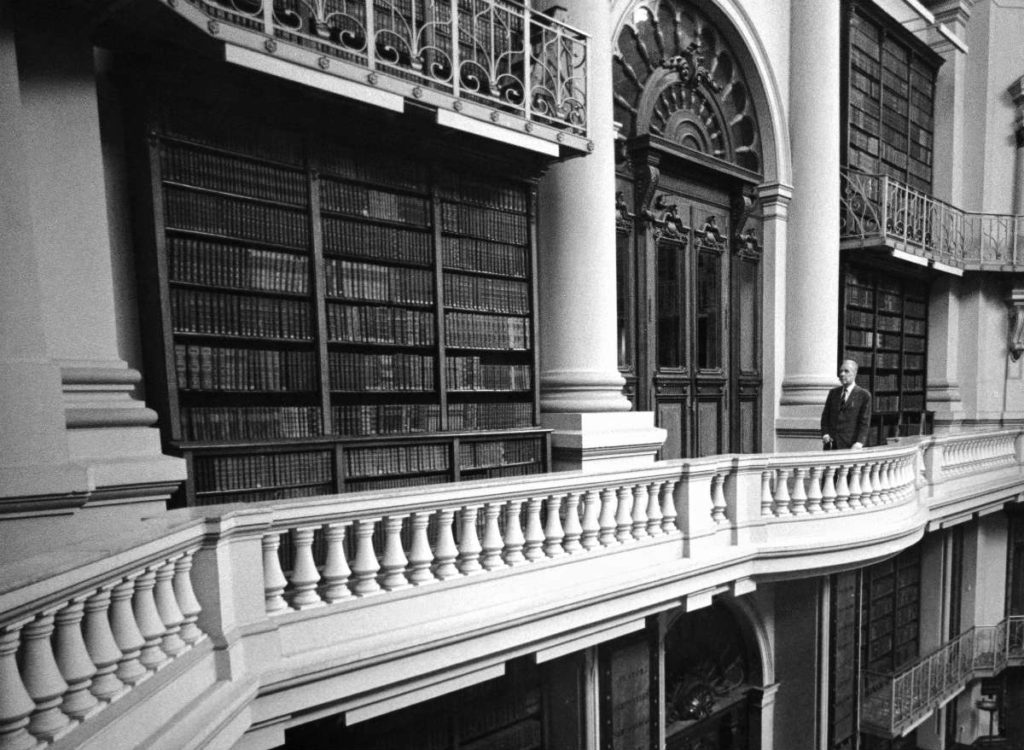

In 1955 the “Revolución Libertadora” took place, and Borges was back in favor. Even though the new government was founded in a military coup, they decided that too much Argentine culture had been damaged under the gentle care of Juan Domingo and his lovely wife Evita. The Sociedad Argentina de Escritores was reopened, and much to his amazement, Borges was appointed Director of the National Library—the job of his dreams. Naturally, by this time Borges was nearly blind; interestingly, two of the previous directors of the National Library had also been blind. He took it as stoically and gently as possible: “I speak of God’s splendid irony in granting me at one time 800,000 books and darkness.”

Determined to transform the National Library into a model cultural center, Borges resurrected the library’s moribund journal and initiated an exciting program of lectures. In 1956 he was appointed to the professorship of English and American Literature at the University of Buenos Aires, a position he was to hold for twelve years. Later that same year, he unsurprisingly won the National Prize for literature. Now in his late fifties, Borges was astonished to find that books were being written about his life and work, and he attracted a wide circle of students and admirers. It was around this time that he wrote one of his most intriguing pieces, “Borges and I.”

Borges at the National Library

With the assistance of his students and his mother, who had begun to translate English classics into Spanish, Borges continued to advance his career through his blindness. He turned again to poetry, a form of writing that could be more easily revised in his head. He continued his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, acquiring a taste for the Anglo Saxon language and learning the rudiments of Old Norse. In 1960 Borges published El hacedor, or “The Maker,” which was later retitled in English as Dreamtigers. Areflective collection of prose pieces, parables, and poems, Borges considered El hacedor to be his best, and most personal, work.

An End to Solitude: The Sixties

As a consequence of that prize, my books mushroomed overnight throughout the western world.

—Borges, on the Formentor Prix International

In 1961 Borges won the first-ever Formentor Prix International, a new award dedicated to honoring those authors whose work will “have a lasting influence on the development of modern literature.” Conceived and awarded by a panel of five international publishers—including New York’s Grove Press—the first prize of $10,000 was divided between Borges and the Irish expatriate Samuel Beckett. Although neither Borges nor the Prix Formentor were well known to the world at large, one of the benefits of the award was the translation and publication of the recipient’s work in each country represented by the panel: Spain, Italy, England, the United States, and Germany. Ficciones became the first Latin American work to achieve such attention, and Borges found himself in the international spotlight. Grove Press published the English translation of Ficciones to great acclaim, and New Directions issued a collection of Borges’ stories and essays called Labyrinths.

Borges was invited to the University of Texas. Accompanied by his mother—who had shifted the focus of her care from her blind husband to her blind son—Borges experienced the United States for the first time, a country he had always considered in semi-mythic proportions. He spent six months traveling across the States, lecturing at universities from San Francisco to New York. He would visit the U.S. numerous times over the rest of his life, giving lectures, readings, and informal discussions, writing in 1970, “I found America the friendliest, most forgiving, and most generous nation I had ever visited. We South Americans tend to think of things in terms of convenience, whereas people in the United States approach things ethically. This—amateur Protestant that I am—I admired above all. It even helped me overlook skyscrapers, paper bags, television, plastics, and the unholy jungle of gadgets.”

In 1963 Borges returned to Europe, revisiting formative locations from his adolescence and reconnecting with old friends and comrades. In 1967 he was invited by Harvard to spend a year in the U.S. as a visiting professor. There he met Norman Thomas di Giovanni, who would become a good friend, a literary collaborator, and one of his principal English translators.

Borges speaking in Madrid, 1963

That same year Borges married his old friend Elsa Astete Millán, whose husband had died in 1964. Unfortunately it was not a fulfilling union for either partner. Millán had grown accustomed to the comforts of a settled existence, and Borges was still enjoying his global excursions. Millán spoke only Spanish, and she felt uncomfortable traveling in the United States or entertaining English-speaking guests. In 1970 Borges and Millán obtained a divorce, and Borges moved back in with his mother.

Throughout these years Borges continued to travel, visiting England, Scotland, Israel, and eventually Japan. He wrote more poetry, and assembled collections of stories and essays. In 1967—the year that Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude introduced the world to Borges doppelgänger Melquíades—he and Bioy Casares collaborated on The Chronicles of Bustos Domecq. In 1970 Borges published a collection of more traditionally “Argentine” stories called El Informe de Brodie, or “Dr. Brodie’s Report.” He developed an acquaintance with a student who attended his lectures, María Kodama, an Argentine with Japanese ancestry. She agreed to work as his secretary, and eventually their association blossomed into a collaborative friendship. He would marry Kodama during the final year of his life.

So Many Mirrors: The Long, Wandering Autumn

I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all the people that I have met, all the women that I have loved; all the cities that I have visited, all my ancestors … Perhaps I would have liked to be my father, who wrote and had the decency of not publishing. Nothing, nothing, my friend; what I have told you: I am not sure of anything, I know nothing … Can you imagine that I not even know the date of my death?

—Jorge Luis Borges

In 1973 Juan Perón returned from exile and was again elected president of Argentina. Although Borges’ global fame now protected him from overt persecution, he refused to be a part of Perón’s government. He resigned as Director of the National Library, and decided to spend the next few years lecturing, producing another collection of stories, El libro de arena, or “The Book of Sand” in 1975. That same year, Borges’ mother died at the age of 99. Long ago people had begun mistaking Borges and his mother as brother and sister; the blow was a hard one.

When Perón’s widow Isabel “La Presidente” was ousted by the traditional military coup in 1976, Borges began another one of his periodic flirtations with politics. Harking back to his attitude toward Hipólito Yrigoyen, Borges extended a good-faith welcome of the new government of Jorge Rafael Videla; a political stance that earned him the surprised disappointment of the Argentine left. But as mounting evidence pointed to serious human rights violations, Borges began to openly criticize the regime’s restrictive policies. The final straw was Leopoldo Galtieri’s “absurd war” over the Falkland Islands, and Borges withdrew from politics for the last time.

Borges and María Kodama

Now accompanied by María Kodama, Borges continued traveling around the world. In 1984 he published his last major work, a collaboration with Kodama called Atlas. Presenting their travels together as a mythic journey of discovery through time and space, the book is a compendium of Borges’ eclectic reflections and Kodama’s black and white photographs. It was during these adventures that Borges had the chance to fulfill a childhood dream—stroking the fur of a living tiger. Unfortunately, the tiger’s thoughts are unrecorded.

Two years later, near the end of his long and marvelous life, Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama were married. On June 14, 1986, at the age of 86 and having never won the Nobel Prize for Literature, Jorge Luis Borges died of liver cancer in Geneva.

A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the image of his own face.

—Afterword to El hacedor, 1960

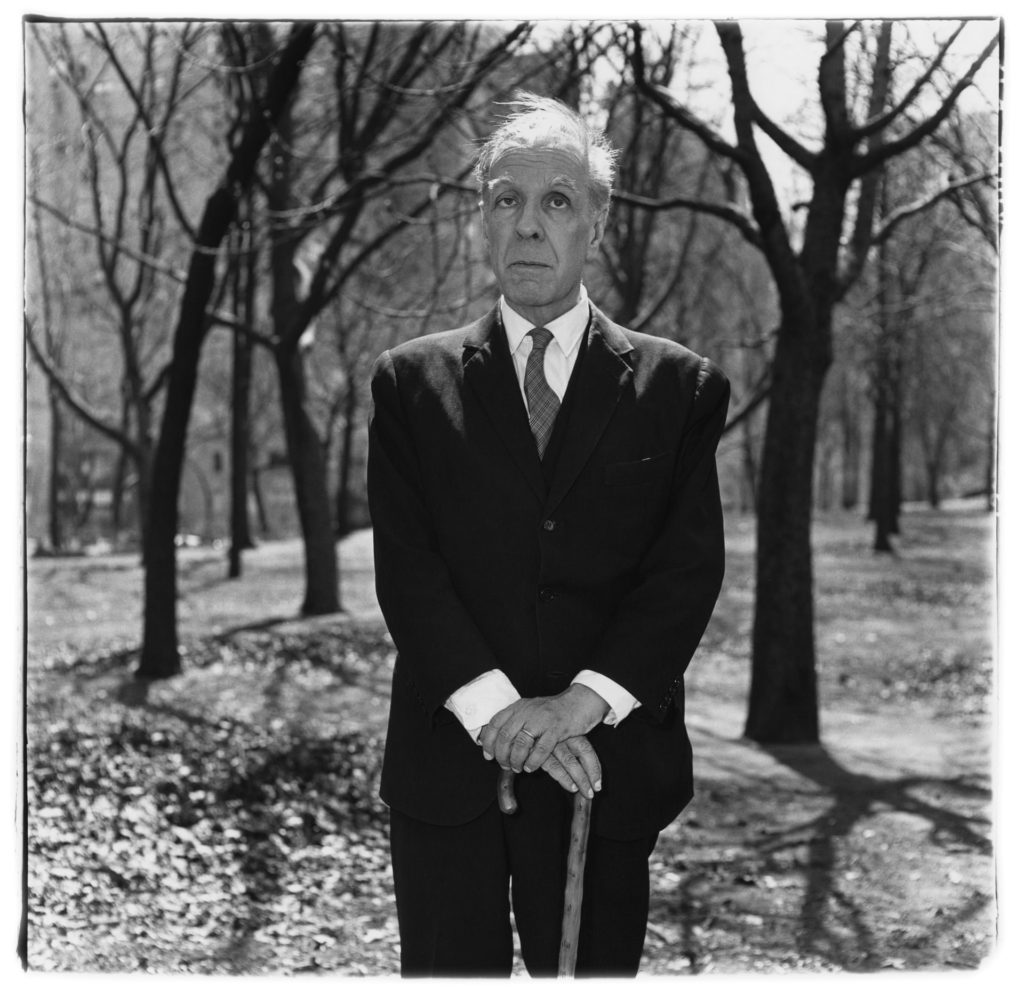

Borges in 1969, photographed by Diane Arbus

Borges in 1969, photographed by Diane Arbus

Timeline

The best Borges timeline is unquestionable the one published by the Borges Center and edited by Daniel Balderston. The Borges Timeline features every publication date, contains links to videos, and features dozens of photographs. A tremendous Borges resource!

Sources and Notes

The original version of this biographical sketch was uploaded to The Garden of Forking Paths in 1997. It was expanded in 2005, and extensively revised again in 2019. Much of the information comes from Borges himself, and is found in his “Autobiographical Essay” of 1970, various prologues to his revised collections, personal letters, essays, and interviews, particularly those with Richard Burgin and Osvaldo Ferrari. I also consulted the following books:

King, John Peter. Sur: A Study of the Argentine Literary Journal and Its Role in the Development of a Culture 1931-1970.

Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Lennon, Adrian. Jorge Luis Borges.

New York: Chelsea House, 1992.

Monegal, Emir Rodríguez. Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography.

New York: Paragon House, 1978.

Sorrentino, Fernando. Seven Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges.

Troy, NY: Whitson, 1981.

Sturrock, John. “Introduction to Ficciones.”

New York, NY: Knopf Everyman’s Library, 1993.

Williamson, Edwin. Borges: A Life.

New York, NY: Viking, 2004.

Woodall, James. Borges: A Life.

New York, NY: Basic Books/HarperCollins, 1996.

I would like to thank Emiliano Canal, who informed me about several aspects of Buenos Aires history and society. The following kind contributors have also offered me suggestions, recollections, and corrections: Ivan Almeida, Pablo Kaufer, Javito Mendia, Gabriel Mesa, Francisco de Monasterio, and Diego Papic. The information about Jorge Guillermo Borges’ novella El Caudillo comes from a review in Página 12 by Alejandro Soifer, originally published on 14 June 2009.

Images

There are thousands of photographs of Borges around the Web, and crediting each of my sources seems like a tedious task worthy of the Miguel Cané Library! Suffice it to say there are enough copies floating around that I feel free to borrow at will. Having said that, many of the early photographs and photos of Borges’ family come from the Helft Collection, an archive managed by Jorge, Marion, and Nicolás Helft, a family of art collectors in Buenos Aires. Those images were used with permission through the Jorge Luis Borges Centre.

Pronunciation

And finally, a note on pronunciation for the non-Spanish speakers who’ve heard the name “Borges” pronounced to rhyme with “gorges.” Like many Spanish g’s and j’s, the “g” in Borges is pronounced in a raspy guttural fashion. Borges is pronounced more like “BOR-hays,” with the gap between two syllables sounding like a growl in the back of the throat, like the “ch” in the German “Achtung” or the Scottish “loch.” So his entire name is (loosely) pronounced HOR-hay LWEES BOR-hays. According to Borges, when he was in school in Switzerland, the teachers pronounced his name with one syllable in the French manner, as to rhyme with “Forge.” This evidently caused the poor lad some confusion!

Borges Biography & Memoir

Main Page — Return to the Borges Biography & Memoir main page and index.

Borges Biographies — English-language biographies written about Borges.

Borges Memoirs — This page details memoirs about Borges by his friends and associates.

Author: Allen Ruch

Last Modified: 5 August 2024

Borges Main Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

Elegy

Oh destiny of Borges

to have sailed across the diverse seas of the world

or across that single and solitary sea of diverse names,

to have been a part of Edinburgh, of Zurich, of the two Cordobas,

of Colombia and of Texas,

to have returned at the end of changing generations

to the ancient lands of his forebears,

to Andalucia, to Portugal and to those counties

where the Saxon warred with the Dane and they mixed their blood,

to have wandered through the red and tranquil labyrinth of London,

to have grown old in so many mirrors,

to have sought in vain the marble gaze of the statues,

to have questioned lithographs, encyclopedias, atlases,

to have seen the things that men see,

death, the sluggish dawn, the plains,

and the delicate stars,

and to have seen nothing, or almost nothing

except the face of a girl from Buenos Aires

a face that does not want you to remember it.

Oh destiny of Borges,

perhaps no stranger than your own.

– Jorge Luis Borges