Borges Collaborations with Bioy Casares

- At July 26, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

[We] met in 1930 or 1931, when he was seventeen and I was just past thirty. It is always taken for granted in these cases that the older man is the master and the younger his disciple. This may have been true at the outset, but several years later, when we began to work together, Bioy was really and secretly the master.

—Jorge Luis Borges on Adolfo Bioy Casares

Borges Works: Collaborations with Adolfo Bioy Casares

Borges enjoyed collaborating with other writers, translators, and artists. He began his career by translating Oscar Wilde, helped his father write a historical novel named El Caudillo, and worked closely with his sister Norah Borges to illustrate his early poems. Borges frequently struck up friendships with his translators, and his work with Norman Thomas di Giovanni is considered definitive by many English readers. Borges’ penultimate work was a travelogue written with his future wife, María Kodama. Of all these relationships, however, his partnership with Adolfo Bioy Casares was the most fruitful, and deserves its own section in “Borges Works.”

Adolfo Bioy Casares (1914–1999)

Adolfo Bioy Casares was born in 1914 in Buenos Aires, the only child of Adolfo Bioy Domecq and Marta Ignacia Casares Lynch, upper-class Argentines with French and Irish ancestry. Bioy Casares dropped out of school to focus on his literary career, spending much of his time writing at his family’s ranch, Rincón Viejo. He met Borges in 1932 during one of Victoria Ocampo’s literary soirees. Bioy Casares was only eighteen years old, but the two writers bonded immediately, and were even reprimanded by their hostess for monopolizing each other’s attention! Soon after their meeting, Bioy Casares began dating Victoria’s younger sister, the poet and painter Silvina Ocampo. In 1936 Borges and Bioy Casares founded an avant-garde literary magazine named Destiempo, or “Out of Time.” The following year Bioy Casares’ father helped Borges secure his first job, the fateful position at the Miguel Cané Library where he’d write many of his famous stories.

During their forty-year creative partnership, Borges and Bioy Casares collaborated on numerous stories and essays, edited several anthologies, published four collections of “Bustos Domecq” stories, and wrote five film scripts. Borges wrote the introduction to Bioy Casares’ most successful novel, La invención de Morel, or “The Invention of Morel,” a dreamy work of science fiction he favorably compared to Kafka, Verne, and Wells. In 1940, Bioy Casares married Silvina Ocampo, and together the three edited and produced Latin America’s first anthology of fantastic literature.

Adolfo Bioy Casares had a long and successful career, winning the Légion d’honneur in 1981 and the Miguel de Cervantes Prize in 1991. He was also known for his romantic entanglements, and two of Bioy Casares’ children were born outside his marriage to Silvina, who died in 1993. Adolfo Bioy Casares died in 1999 in Buenos Aires, and is buried at La Recoleta Cemetery.

Wedding of Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo, 1940.

Borges standing at the left.

Working together in one of the back rooms of Bioy’s apartment, they reminded me of alchemists assembling a homunculus, creating something that was a combination of the features of both men and yet was unlike either of them. In that new voice which was neither as satirical as that of Bioy nor as cerebral as that of Borges, they composed the stories and mock essays of H. Bustos Domecq, an Argentine gentleman of letters who looked with a seemingly innocent eye at the absurdities of Argentine society.

—Alberto Manguel, “Con Borges”

The works below are arranged in chronological order, with English translations appearing after the slash. Their film scripts are discussed at the Garden’s “Borges and Film” section.

Antología de la literatura fantástica / The Book of Fantasy (1940)

Seis problemas para Don Isidro Parodi / Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi (1942)

Los mejores cuentos policiales (1943)

Dos fantasías memorables (1946)

Un modelo para la muerte (1946)

Los mejores cuentos policiales II (1951) /Los mejores cuentos policiales (2019)

Los orilleros/El paraíso de creyentes (1955)

Cuentos breves y extraordinarios / Extraordinary Tales (1955)

Libro del cielo y del infierno (1960)

Crónicas de Bustos Domecq / Chronicles of Bustos Domecq (1967)

Nuevos cuentos de Bustos Domecq (1977)

Museo: Textos inéditos (2002)

Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com, unless it’s the original first edition, which just enlarges the image. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online” editions may or may not match the publisher and publication date of their corresponding book.

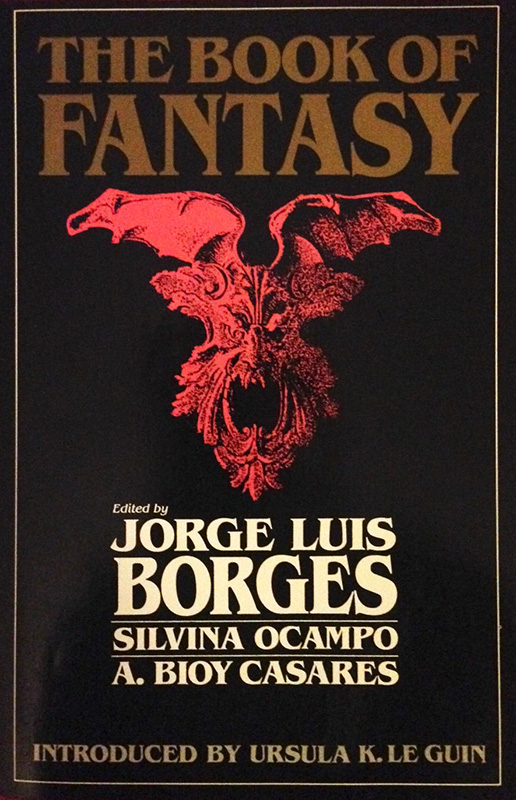

Antología de la literatura fantástica

The Book of Fantasy

Antología de la literatura fantástica

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges, Silvina Ocampo & A. Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1940

Online at: Internet Archive

The Book of Fantasy

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges, Silvina Ocampo & A. Bioy Casares

Translation by Anthony Kerrigan. Introduction by Ursula K. LeGuin

Viking, 1988

Online at: Internet Archive

The origins of this anthology may be traced an evening in 1937 when Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, and Silvina Ocampo spent the night discussing “fantastic literature,” a subject particularly dear to Bioy Casares. The fruit of their conversation was an anthology of classic and contemporary fantasy, published in 1940 as Antología de la Literatura Fantástica. The volume was revised twice, first in 1965 and again in 1976. It was translated into English in 1988 with an introduction by Ursula K. LeGuin. According to Bioy Casares, the anthology is “simply a compilation of stories from fantastic literature which seemed to us to be the best.” Culled from diverse sources ranging from Chinese ghost stories to contemporary issues of Weird Tales, the anthology features short stories, parables, extracts from novels, and even Zen koans.

The contents of the English edition are as follows:

- Introduction by Ursula K. Le Guin

- “Sennin,” by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, 1951

- “A Woman Alone with Her Soul,” by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

- “Ben-Tobith,” by Leonid Andreyev

- “The Phantom Basket,” by John Aubrey

- “The Drowned Giant,” by J. G. Ballard

- “Enoch Soames,” by Max Beerbohm

- “The Tail of the Sphinx,” by Ambrose Bierce

- “The Squid in Its Own Ink,” by Adolfo Bioy Casares

- “Guilty Eyes,” by Ah‘med Ech Chiruani

- “Anything You Want!…” by Léon Bloy

- “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” by Jorge Luis Borges

- “Odin,” by Jorge Luis Borges & Delia Ingenieros

- “The Golden Kite, the Silver Wind” Ray Bradbury

- “The Man Who Collected the First of September, 1973,” by Tor Åge Bringsvaerd

- “The Careless Rabbi,” by Martin Buber

- “The Tale of the Poet,” by Sir Richard Burton

- “Fate Is a Fool,” by Arturo Cancela & Pilar de Lusarreta

- “An Actual Authentic Ghost,” from Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle

- “The Red King’s Dream,” by Lewis Carroll

- “The Tree of Pride,” by G. K. Chesterton

- “The Tower of Babel,” by G. K. Chesterton

- “The Dream of the Butterfly,” by Chuang Tzu

- “The Look of Death,” by Jean Cocteau

- “House Taken Over,” by Julio Cortázar

- “Being Dust,” by Santiago Dabove

- “A Parable of Gluttony,” by Alexandra David-Neel

- “The Persecution of the Master,” by Alexandra David-Neel

- “The Idle City,” by Lord Dunsany

- “Tantalia,” by Macedonio Fernández

- “Eternal Life,” by J.G. Frazer

- “A Secure Home,” by Elena Garro

- “The Man Who Did Not Believe in Miracles,” by Herbert A. Giles

- “Earth’s Holocaust,” by Nathaniel Hawthorne

- “Ending for a Ghost Story,” by I.A. Ireland

- “The Monkey’s Paw,” by W.W. Jacobs

- “What Is a Ghost?,” by James Joyce

- “May Goulding,” by James Joyce

- “The Wizard Passed Over,” by Don Juan Manuel

- “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk,” by Franz Kafka

- “The Return of Imray,” by Rudyard Kipling

- “The Horses of Abdera,” by Leopoldo Lugones

- “The Ceremony,” by Arthur Machen

- “The Riddle,” by Walter de la Mare

- “Who Knows?,” by Guy de Maupassant

- “The Shadow of the Players,” by Edwin Morgan

- “The Cat,” by H.A. Murena

- “The Story of the Foxes,” by Niu Chiao

- “The Atonement,” by Silvina Ocampo

- “The Man Who Belonged to Me,” by Giovanni Papini

- “Rani,” by Carlos Peralta

- “The Blind Spot,” by Barry Perowne

- “The Wolf,” from Patronius’ Satyricon

- “The Bust,” by Manuel Peyrou

- “The Cask of Amontillado,” by Edgar Allan Poe

- “The Tiger of Chao-ch’êng,” from Liao Chai by Pu Songling

- “How We Arrived at the Island of Tools,” by François Rabelais

- “The Music on the Hill,” by Saki

- “Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched,” by May Sinclair

- “The Cloth Which Weaves Itself,” from Malay Magic by Walter William Skeat

- “Universal History,” by Olaf Stapledon

- “A Theologian in Death,” by Emanuel Swedenborg

- “The Encounter,” from the T’ang Dynasty (618-906 CE)

- “The Three Hermits,” by Leo Tolstoy

- “Macario,” by B. Traven

- “The Infinite Dream of Pao-Yu,” by Ts’ao Chan (Hsueh Ch’in)

- “The Mirror to Wind-and-Moon,” by Ts’ao Chan (Hsueh Ch’in)

- “The Desire to Be a Man,” by Villiers de l’Isle-Adam

- “Memnon, or Human Wisdom,” by Voltaire

- “The Man Who Liked Dickens,” by Evelyn Waugh

- “Pomegranate Seed,” by Edith Wharton

- “Lukundoo,” by Edward Lucas White

- “The Donguys,” by Juan Rodolfo Wilcock

- “Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime,” by Oscar Wilde

- “The Sorcerer of the White Lotus Lodge,” by Richard Wilhelm

- “The Celestial Stag,” by G. Willoughby-Meade

- “Saved by the Book,” by G. Willoughby-Meade

- “The Reanimated Englishman,” by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

- “The Sentence” by Wu Ch’Eng En

- “The Sorcerers,” by William Butler Yeats

- “Fragment” from Don Juan Tenorio

Additional Information

The Wikipedia Page for The Book of Fantasy includes links to all the original sources. Laurence Coven provides a contemporary review of the anthology in the 1989 March 26 L.A. Times.

Seis problemas para Don Isidro Parodi

Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi

Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares (as “H. Bustos Domecq”)

Buenos Aires: Sur, 1942

Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares (as “H. Bustos Domecq”)

Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

New York: E.P. Dutton, 1981

Available Online at: Internet Archive

This work is a collection of mystery parodies written under the pen name Honorio “Bugsy” Bustos Domecq, a pseudonym that combines the family names of both Borges and Bioy Casares. (In fact, Borges’ first pen name was “Francisco Bustos,” used when he published “Streetcorner Man” in Crítica.) The stories feature Don Isidro Parodi, a detective confined to a jail cell in Buenos Aires. A spoof of the popular “armchair mystery,” each story features a suitably flamboyant character who arrives at Cell 273 to consult the master. After hearing his visitor’s woeful narrative, the vain Don Isidro solves the crime through the powers of his prodigious intellect, usually punctuating his conclusion with a dose of pompous moralizing. Although the stories serve as quirky send-ups of the genre, their primary purpose is to satirize Argentine society, and the latter “problemas” contain thinly-disguised critiques of right-wing politics.

For years it was not made known that “Bustos Domecq” was really Borges and Bioy Casares.

The contents are as follows:

- Foreword by Gervasio Montenegro

- The Twelve Figures of the World

- The Nights of Goliadkin

- The God of the Bulls

- Free Will and the Commendatore

- Tadeo Limardo’s Victim

- Tai An’s Long Search

- Bustos Domecq by Adelma Badoglio

On an interesting side-note, in 1946 Borges and Bioy Casares collaborated on another parodic mystery story named “Un modelo para la Muerte.” Even though “A Model for Death” borrowed characters from the Parodi stories, they used the pseudonym “Benito Suárez Lynch.”

Los mejores cuentos policiales

Los mejores cuentos policiales

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1943

In 1943 Borges and Bioy Casares published a small anthology called Los mejores cuentos policiales, or “Best Police Stories.” The work included Spanish translations of their favorite detective and crime stories, as well as Borges’ own “La muerte y la brújula” (“Death and the Compass”), which had recently appeared in Sur. Remarking upon their selection, Borges wrote, “To choose the texts in this volume we have followed the only possible criterion—the hedonic criterion. Reading each of the pieces that make up it was very pleasant for us.”

Los mejores cuentos policiales contains 17 stories by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, Jack London, Guillaume Apollinaire, G.K. Chesterton, Eden Phillpotts, Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Anthony Berkeley, Milward Kennedy, Ellery Queen, Georges Simenon, Manuel Peyrou, Silvina Ocampo, and Adolfo Luis Pérez Zelaschi.

Dos fantasías memorables

Dos fantasías memorables

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares (as “H. Bustos Domecq”)

Illustrations by Xul Solar

Buenos Aires: Oportet y Haereses, 1946

Dos fantasías memorables

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Edicom S.A., 1970

Published privately by Borges and Bioy Casares in a limited 300-edition run, Dos fantasías memorables, or “Two Memorable Fantasies” is a 34-page volume containing a pair of new Bustos Domecq stories, “El testigo” and “El signo.” (“The Witness” and “The Sign.”) Detective stories vaguely in the supernatural vein of Edgar Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle, the fantasías lack Don Isidro Parodi, but continue the authors’ playful parody of the mystery genre. The original book had illustrations by Xul Solar. In 1970, Edicom released a new printing of Dos fantasías memorables under the name of its actual authors, but without their friend’s illustrations. In 1998 Editorial Emecé paired Dos fantasías memorables with Un modelo para la muerte in a single volume (see below).

Un modelo para la muerte

Un modelo para la muerte

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares (as “Benito Suárez Lynch”)

Buenos Aires: Oportet y Haereses, 1946

Un modelo para la muerte

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Edicom S.A., 1970

Dos fantasías memorables/Un modelo para la muerte By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares Buenos Aires: Editoriales Emecé, 1998 Available Online at: Internet Archive |

Dos fantasías memorables/Un modelo para la muerte By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares Madrid: Alianza Editorial S.A., 1999 |

Published privately by Borges and Bioy Casares in a limited 300-edition run, Un modelo para la muerte, or “A Model for Death,” is an 83-page short story written under the joint pen-name “Benito Suárez Lynch,” a pseudonym combining their mother’s surnames. My favorite description comes from the now-defunct Vaguely Borgesian blog:

Un modelo para la muerte is one of the strangest fictions that I have read. Published originally under the shared pseudonym of B. Suarez Lynch, the conceit of this story is that Suarez Lynch was writing, with the explicit approval of “H. Bustos Domecq” (who purportedly wrote the prologue), a sort of fan fiction in which Isidro Parodi would appear in a story that would be a parody of the style that Bustos Domecq parodied in Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi. So…here is a parody of a parody, composed by a pseudonym imitating another pseudonym, all of which ties back into Borges and Bioy Casares. Are you clear on the twists and turns yet?

In 1970, Edicom released a new printing of Un modelo para la muerte under the name of its actual authors. In 1998 Editorial Emecé paired Dos fantasías memorables with Un modelo para la muerte in a single volume, and the two have been conjoined ever since. Unfortunately, there has yet to be an English translation.

Los mejores cuentos policiales: segunda serie

Los mejores cuentos policiales: segunda serie

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1951

Los mejores cuentos policiales

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 2019

In 1943 Borges and Bioy Casares published a small anthology called Los mejores cuentos policiales, or “Best Police Stories.” The work included Spanish translations of their favorite detective and crime stories, as well as Borges’ own “La muerte y la brújula” (“Death and the Compass”), which had recently appeared in Sur. The book was followed in 1951 by Los mejores cuentos policiales: segunda serie, which offered 14 additional stories. The new authors included Wilkie Collins, Hylton Cleaver, Agatha Christie, William Irish, Graham Greene, John Dickson Carr, Michael Innes, Harry Kemelman, and William Faulkner. The “Second Series” also included a story by “H. Bustos Domecq,” the most common pen-name of Borges and Bioy Casares.

In 2019, Sudamericana combined both volumes into one, keeping the original name of Los mejores cuentos policiales.

Los orilleros/El paraíso de creyentes

Los orilleros/El paraíso de creyentes

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Editorial Losada, 1955

This book collects two film scripts written by Borges and Bioy Casares—Los orilleros (1939) and El paraíso de los creyentes (1940). (The Outskirts/The Paradise of Believers.) The book contained a new prologue in which the authors detailed their goal to subvert the romantic tropes of Hollywood with modern themes of alienation and the search for identity:

The two films that make up this book accommodate—or tried to accommodate—the diverse conventions of filmmaking. We were not drawn into writing them with an eye toward innovations. To take up a genre and to make innovations within it seemed excessively rash to us. Predictable, then, the reader of these pages will find the boy-meets-girl and the happy ending; or, as has already been said in the letter to the “magnificent and most victorious Lord, the Lord Cangrande della Scala,” the “tragicum principium et comicum finem,” the perilous reversal and the happy denouement. Quite possibly, such conventions are feeble. In our own case, however, we have noticed how the films that we recall with the greatest emotion—those by von Sternberg and Lubitsch—respect those conventions to no great disadvantage.

These comedies are also conventional in regard to the characters of the hero and heroine. Julio Morales and Elena Rojas, Rail Anselmi and Irene Cruz, are merely subjects of the action, hollow and pliant forms through which the spectator may pass in order to participate in the incidents. No marked peculiarities stand in the way of one’s identification with these characters. One knows that they are young, it is understood that they are attractive, lacking neither in decency nor valor. Let’s leave psychological complexity to others. In Los orilleros (Men from the River Bank) we leave it for the ill-fated Fermín Soriano; in El paraiso de los creyentes (Paradise for Believers), Kubin.

The first film takes place at the end of the 19th century, the second more or less in our own time. Since local and temporal color exist only as a function of differentiation, it is infinitely probable that these qualities will be more noticeable and effective in the first film. In 1951 we know the differentiating characteristics of 1890, but not what in the future will be those of 1951. On the other hand, the present will never seem as picturesque and affecting as the past.

In El paraiso de los creyentes, the basic motive is love of money; in Los orilleros, emulation. Even though this latter motive suggests morally superior characters, we have resisted the temptation to idealize them, and we believe that neither cruelty nor baseness is lacking in the meeting of the stranger with the boys from Viborita. Of course, both films are romantic, in the same sense that Stevenson’s stories are. They are informed by the love of adventure and, perhaps, a distant echo of epics. In El paraíso de los creyentes, the romantic tone is emphasized as the action progresses. We have decided that the excitement proper to the ending will smooth over certain improbabilities that might not have been accepted at the beginning.

The theme of the search is repeated in both pictures. Perhaps it is not beside the point to note that in ancient books searches were always successful: the Argonauts captured the Golden Fleece and Galahad the Holy Grail. Nowadays, in contrast, we are mysteriously pleased by the notion of an unending search or of a search for something that, once found, has ruinous consequences. K., the surveyor, does not enter the castle, and the white whale destroys the one who eventually finds it. In this sense Los orilleros and El paraíso de los creyentes do not deviate from the norm of our times.

Contrary to Shaw’s opinion that writers ought to flee plots like the plague, we have believed for a long time that a good plot is fundamentally important. The difficulty is that in every complex plot there is something mechanical; the episodes that warrant and explain the action are inevitable and perhaps not spellbinding. Sad to say, the insurance and the ranch in our films correspond to these unfortunate necessities.

As for the language, we have tried to suggest the popular, less by means of vocabulary than by tone and syntax.

In order to make the reading easier, we have shortened or deleted technical terms of mise-en-scène, and we have not retained the double-column format.

Up to this point, reader, the logical justification for our work. Yet there are other justifications, of an emotional nature, and we that these latter were more in force than the former. We suspect that the ultimate reason that moved us to imagine Los orilleros was the desire to fulfill our obligation, in some way, to certain suburbs, to certain nights and dawns, to the oral mythology of courage, and to the brave, humble music commemorated by guitars.

—Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, Buenos Aires, 11 December 1951. [Translation by Ronald Christ.]

Of the two scripts, Los orilleros was made into a film in 1975 by Ricardo Luna.

Cuentos breves y extraordinarios

Extraordinary Tales

Extraordinary Tales

Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Translated by Anthony Kerrigan

New York: Herder and Herder, 1971

Online at: Internet Archive

Published under their actual names, Borges and Bioy Casares’ Extraordinary Tales is an anthology of narratives, parables, fragments, and anecdotes ostensibly derived from classic works of literature. Somewhat in the vein of Historia universal de la infamia, these pieces do not appear in their original form, but are paraphrased narratives presented with “episodic illustration, psychological analysis, [and] fortunate or inopportune verbal adornment.” Needless to say, some of them are utter fabrications—presumably.

Additional Information

Rebecca DeWald labels these pieces as “pseudotranslations,” and argues “that the mere existence of a pseudotranslation turns every text into an unreliable construct, as it creates uncertainty over what an original is and where it ends.” You can read more in her paper, “Extraordinary Tales of Authenticity and Pseudotranslations. Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares’s Cuentos.”

Libro del cielo y del infierno

Libro del cielo y del infierno Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares Buenos Aires: Sur, 1960 Online at: Internet Archive |

Libro del cielo y del infierno [Revised & Illustrated Version] Edited by Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1999 |

Published under their actual names, Borges and Bioy Casares’ Libro del cielo y del infierno (“Book of Heaven and Hell”) is an anthology of selections drawn from various religious texts. As they state in their introduction, “We have sought the essential, without neglecting the vivid, the dreamlike and the paradoxical. Perhaps our volume reveals the millenary evolution of the concepts of heaven and hell; from Swedenborg one thinks about states of the soul, and not about an establishment of awards and another of punishments.” As both writers were professed agnostics, their intention is more literary and imaginative than spiritual. Like their work with the Book of Fantasy, their selections are eclectic, ranging from philosophical musings to ritual catechism. In 1999 Emecé released an updated version, complete with illustrations. According to Omar Gonzáles, “It should also be noted that throughout the book there are a series of vignettes and reproductions in black and white of antique prints, drawings and details of paintings that more or less illustrate what is said in immediate texts, but they are not credited or the titles, or the dates, or the name of the authors.” Libro del cielo y del infierno has not been translated into English, and any further commentary is welcome.

Additional Information

I am indebted to Omar Gonzáles and his wonderful literary blog, Las mil notas y una nota, which has a lovely Spanish language review of Libro del cielo y del infierno.

Crónicas de Bustos Domecq

Chronicles of Bustos Domecq

Crónicas de Bustos Domecq

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada S.A., 1967

Online at: Internet Archive

Chronicles of Bustos Domecq

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

New York: E.P. Dutton, 1979

Online at: Internet Archive

By the time Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares were ready for a new collection of Bustos Domecq stories, both had become famous, and “H. Bustos Domecq” was widely recognized as their invention. Borges had published three masterpieces, Ficciones, El Aleph, and Otras inquisiciones, and in 1961 the Formentor Prix International had brought him global recognition. Adolfo Bioy Casares had also achieved greater success, and in 1964 his novel The Invention of Morel was translated into English by Ruth L.C. Simms, the same translator who had worked on Borges’ Otras inquisiciones. Published in 1967, Crónicas de Bustos Domecq proudly announced the names of both authors on the cover. Once the book is opened, however, the insufferable Honorio Bustos Domecq immediately reasserts himself, from meddling in the title credits to thoughtfully supplying his own index.

Borges prefaced his 1954 revision of A Universal History of Infamy by declaring, “I should define as baroque that style which deliberately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its possibilities and which borders on its own parody.” This aesthetic is the animating force behind Crónicas, in which the narcissistic Bustos Domecq abandons his armchair mysteries to focus his genius on cultural criticism, offering pompous observations on everything from abstract art to haute couture. More pointed than the Parodi stories, these “chronicles” offer Borges and Bioy Casares a platform to satirize contemporary critical theory, ridicule avant-garde posturing, and gently critique the excesses of modernism. The chronicles also serve as whimsical parodies of the authors’ own previous work; “deliberate exhaustions” that deconstruct the Borgesian style by carrying its aesthetics into the realm of absurdity. Chronicles is also funnier than Parodi, and admirers of Borges’ mature essays will appreciate the same sharp intelligence, here frequently turned against the conceits made famous by Borges himself.

The contents are as follows:

- Homage to César Paladión

- An Evening with Ramón Bonavena

- In Search of the Absolute

- Naturalism Revived

- A List and Analysis of the Sundry Books of F.J.C. Loomis

- An Abstract Art

- The Brotherhood Movement

- On Universal Theater

- The Flowering of an Art

- Gradus ad Parnassum

- The Selective Eye

- What’s Missing Hurts Not

- The Multifaceted Vilaseco

- Tafas, a Talented Brush

- The Sartorial Revolution (I)

- The Sartorial Revolution (II)

- A Brand-New Approach

- Esse est percipi

- The Idlers

- The Immortals

Nuevos cuentos de Bustos Domecq

Nuevos cuentos de Bustos Domecq

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Ediciones Librería La Ciudad, 1977

Online at: Internet Archive

The fourth and final volume of Bustos Domecq stories, “New Stories by Bustos Domecq” is composed of political and cultural satires. Its most famous piece is a savage critique of the Perón regime, “La fiesta del monstruo.” Nuevos cuentos has yet to be published in an English-language version, and the Garden of Forking Paths welcomes any review or explication.

- Deslindando responsabilidades (“Delinking Responsibilities”)

- El enemigo número 1 de la censura (“The Number 1 Enemy of Censorship”)

- El hijo de su amigo (“The Son of His Friend”)

- La fiesta del monstruo (“The Monstrous Party”)

- La salvación por las obras (“Salvation by Works”)

- Las formas de la Gloria (“The Forms of Glory”)

- Más allá del bien y del mal (“Beyond Good and Evil”)

- Penumbra y pompa (“Twilight and Pomp”)

- Una amistad hasta la Muerte (A Friendship Until Death”)

Museo: Textos inéditos

Museo: Textos inéditos

By Jorge Luis Borges & Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires: Emecé, 2002

Published in 2002 by Emecé, Museo: Textos inéditos (“Museum: Unpublished Texts”) is an anthology of previously uncollected collaborations between Borges and Bioy Casares. The book includes short stories, books reviews, translations, and parodies, many of them having appeared in literary magazines such as Destiempo, Los annals de Buenos Aires, and Sur. It also includes the infamous “Curdled Milk Brochure” commissioned by the Argentine dairy La Martona. Museo has yet to be translated into English.

Borges Works

Main Page — Return to the Borges Works main page and index.

Fictions and Artifices — Short stories; the core Borges works.

Nonfiction — Collections of essays and criticism.

Collaborations with Others — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with others.

Poetry Compilations — Selections of Borges’ verse translated into English and published as compilations.

Poetry I — Early post-ultraísmo poetry, 1923 to 1943.

Poetry II — Mid-career collections from 1944 to 1969.

Poetry III — Late poetry books from 1969 to 1985.

Lectures, Conversations, and Interviews — Collections of Borges’ lectures, conversations, and interviews.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 9 August 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com