Borges Music – Robert Parris

- At September 18, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

Robert Parris (1924–1999)

American composer Robert Parris was born in Philadelphia and attended the University of Pennsylvania before enrolling in Juilliard. He studied under Otto Luening and Aaron Copland, but developed a highly individual style known for musical color and placing virtuosic demands on the players. Parris’ violin sonata is considered quite difficult, and composer-directors of CRI believed his trombone concerto was unplayable until they heard a recording of it! He also wrote music criticism for The Washington Post and the Kenyon Review. Parris taught himself Spanish to better understand Borges, a writer who inspired one of his most enduring pieces, The Book of Imaginary Beings. Renown for his sense of humor, Parris composed the Concerto for Five Kettledrums and Orchestra in 1958—a dramatic work that began with a jest, but was soon championed by Mtislav Rostropovich himself.

Robert Parris died of lung cancer on 5 December 1999.

Borges-Related Works

The Book of Imaginary Beings (1972)

Inspired by The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges and Margarita Guerrero, this chamber work is a suite of seven musical portraits and a reprise. See below for details.

The Book of Imaginary Beings (Part 2) (1983)

A sequel to Parris’ Book of Imaginary Beings, Part 2 was published in 1983 but has never been performed. It is described below.

The Book of Imaginary Beings

(1971-1972)

For flute, violin, cello, piano, celesta, and percussion

I. Amphisbaena

II. The Rain Bird

III. A King of Fire and His Steed

IV. A Bao a Qu

V. The Satyrs

VI. The Double

VII. Sirens

VIII. Amphisbaena Retroversa

As I was listening to The Book of Imaginary Beings, my wife—a fan of Italian opera as well as Shostakovich, so someone familiar with the extremes of tonal composition—walked into the room and laughed, “This is crazy music!” She returned a little while later and said, “Well, this is beautiful. It’s not the same work, is it?”

Yes, it was the same work, and she was right—this is crazy music, and also beautiful music, and occasionally both at once. A suite composed of eight pieces, Robert Parris’ The Book of Imaginary Beings is inspired by the fantastical creatures of its namesake, and the results are as imaginative and inventive as Borges’ original. Wisely, Parris treats his imaginary beings as “symbols of inner reality.” This allows him to explore states of mental being rather than simply crafting soundtrack cues. Parris has a reputation as an innovative composer with a highly individual voice and a generous sense of humor, and The Book of Imaginary Beings gives him the opportunity to indulge his diverse talents. Each of these animated profiles is a musical gem, perfectly cut and brilliantly colored. All elements of the ensemble are balanced marvelously, whether playing together or matched as intimate pairings.

Parris has named the violin his favorite instrument, and it plays a dominate role throughout The Book of Imaginary Beings, whether providing a cohesive narrative or engaging in playful duets. It is the first instrument heard in the suite, its frantic sawing cutting loose the “Amphisbaena,” the two-headed snake of Greek antiquity. An explosively kinetic piece, each instrument comes to life in a flickering maze of sound, bringing to mind the orchestrated chaos of Edgar Varèse or the later Frank Zappa.

This energy is passed on to “The Rain Bird,” a whirling dance of violin and flute that concludes in a rain of chiming notes. The next piece is the longest, “A King of Fire and His Steed.” A mysterious melodic line is introduced by the violin and picked up by the flute. Conjuring the ghostly horseman from William Morris’ poem The Ring Given to Venus, violin and flute weave around each other like cold, spectral flames above a cantering percussion. “A Bao a Qu” is even more ethereal. One of Borges’ most abstract creatures, this spirit of possession and enlightenment is embodied by the violin, floating above a subdued drumbeat and the hazy meanderings of a celesta. Otherworldly and beautiful, it feels like a musical apparition, a mesmerizing cloud of ectoplasm that vanishes in a shimmer of cymbals.

A gong announces the arrival of “The Satyrs.” As a flute unspools a lazy and formless melody, spasms of percussion serve as reminders of the satyr’s bestial nature. While it may be too simple to reduce the piece to syrinx and hoofbeat, it’s the most obviously programmatic piece in the suite, and ends with a listless tapering off—perhaps these satyrs succumbed to wine rather than lust? “The Double” announces itself with a quick drumroll. The cello and piano play the melody from Saint-Saëns’ “The Swan,” itself a creature from another musical suite, The Carnival of Animals. This lovely melody is cheerfully battered by the rest of the orchestra—shrieking strings, tubular bells, stuttering drumbeats. Charles Ives’ Putnam Camp marching band turned loose in a nineteenth century salon, “The Double” is a cheeky study of unresolved oppositions. In the end, neither order nor chaos are triumphant, the only resolution being a mutual agreement to wind down together.

The spirited frenzy of “The Double” is followed by the languid timelessness of “The Sirens.” Once again the violin offers the principal melodic line, floating above an eerie soundscape of celesta and flute. A spell of dreamy paralysis, “The Sirens” evokes a strange mixture of beauty and dread, Ulysses lashed helplessly to the mast as his sailors succumb to a fatal illusion. The Book of Imaginary Beings concludes with “Amphisbaena Retroversa,” the introductory piece played in reverse, closing the loop with a musical palindrome.

Liner Notes (VOX LP)

By Robert Parris

Parris/Evett: The Book of Imaginary Beings/Quintet for Piano & Strings

VOX/Turnabout, 1974

Just as imaginary beings are, almost by definition, symbols of inner reality, the eight pieces that constitute The Book of Imaginary Beings are expressions of elusive, vague, mysterious and occasionally mystical states of feeling evoked by associative imagery. Its literary source is the book of the same name by Jorge Luis Borges—a compendium, really, of the more illustrious creatures of the mind.

It follows that no realistic musical portrayal of unreal beings was intended. To those who hear, for instance, a horse’s hooves in “The King of Fire and His Steed” (No. 3), I can say only that I am astonished.

“The Rain Bird” (No. 2) is what I call “flight music”; to the visual-minded, any number of more concrete images might present themselves. The drums in No. 4 might suggest a coming-to-life, or heart-beat; actually, they derive from the beating in my clogged ears during a bad cold. The siren-call in No. 7 is clear even to me, however. As for “The Satyrs” (No. 5), I can add nothing to what is implicit in the image of those lascivious beasts who set upon nymphs and play—probably not incidentally—the flute.

“The Double” (or Doppelgänger, No. 6) is a gloss or commentary on a pretty piece by Saint-Saëns: what “The Swan” is to the flesh-and-blood animal, my setting is to its fancied, incorporeal image. The set opens and closes with the same music going in the opposite direction. The ferocious amphisbaena’s end is not really its beginning: its shape is a line, not a circle. But it is a bestial palindrome (and now a musical one) which is, after all, a very good reason for being an imaginary being.

Here are the superscriptions to the several movements, adapted from Borges’s bestiary:

I. AMPHISBAENA. “The amphisbaena is a serpent having two heads, the one in its proper place and the other in its tail; and it can bite with both… Amphisbaena, in Greek, means ‘goes both ways.’’

II. THE RAIN BIRD. “When rain is needed, Chinese farmers have at their disposal…the bird called the ‘shang yang’… The tradition runs that the bird drew water from the rivers with its beak and blew it out as rain on the thirsting field.”

III. A KING OF FIRE AND HIS STEED. “This almost unimaginable fancy was attempted by William Morris in the tale ‘The Ring Given to Venus’…

As a white flame his visage shown,

Sharp, clear-cut as a face of stone;

But flickering flame, not flesh it was;

And over it such looks did pass

Of wild desire, and pain, and fear,

As in his people’s faces were,

But tenfold fiercer…

IV. A BAO A QU. “There has lived since the beginning of time a being sensitive to the many shades of the human soul. It lies dormant…until at the approach of a person some secret life is touched off in it, and deep within the creature an inner light begins to glow.”

V. THE SATYRS. “Satyrs were thickly covered with hair and had short horns, pointed ears, active eyes, and hooked noses. They were lascivious and fond of their wine. They set ambushes for nymphs…and their instrument was the flute.”

VI. THE DOUBLE. “The ancient Egyptians believed that the Double, the ‘ka,’ was a man’s exact counterpart, having his same walk and his same dress. Not only men, but gods and beasts…had their ‘ka.’ In Yeats’s poems the Double is…the one who complements us, the one we are not nor will ever become.” [Parris’ later addition for the CRI liner notes: This piece is a gloss on a pretty piece by Saint-Saëns: his music represents the bird’s superficial beauty; mine, its latent inner ferocity, both aspects in collage. The white swan and the black swan, as it were.]

VII. SIRENS. “The Odyssey tells that the Sirens attract and shipwreck seamen, and that Ulysses, in order to hear their song and yet remain alive, plugged the ears of his oarsmen…and had himself lashed to the mast…In the sixth century, a Siren was caught and baptized in northern Wales…”

VIII. AMPHISBAENA RETROVERSA.

Interview Excerpts

From a Robert Parris interview conducted by Bruce Duffie in 1988

Parris: I’ve written some funny music, some very funny music. There’s a piece you have on a record, which is No. 6 from The Book of Imaginary Beings is called The Double. When I wrote that piece, I read the superscription that is appended to it, and it’s actually one of the fables of Borges in his book of the same name, and apparently animals, just as people, have two sides to themselves. [Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges KBE (24 August 1899—14 June 1986), was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, and a key figure in Spanish-language literature.] The Double represents the opposite nature from this obvious self. Whether it’s your true self or not, no one knows. The first thing I thought of was how could I do this in music, and I thought of the silly Swan of Camille Saint-Saëns, and how this blithe creature sits practically motionless on the water, but is so idyllic. But the fact is everybody knows that there’s a lot of aggression to that animal. It’s really a mean beast, so don’t tangle with any swans. So I put together my idea of the ferocity of the swan, and I simply copied over, note for note, the original Saints-Saëns, not abrogating nor breaking any copyright laws, I assume. Actually it wasn’t quite the original because he wrote it for two pianos, and I have it played by one. I can’t hear it today without laughing. It’s one of the funniest things I’ve ever heard in my life. So yes, I hope my music is sometimes funny, and sometimes entertaining in the light sense, and lots of times otherwise.

Duffie: Tell me more about The Book of Imaginary Beings.

Parris: Well, that’s a little difficult. I tend to forget pieces the day after I write them.

Duffie: OK… Is it something that must be played always complete, or can we play a few of them?

Parris: I don’t see why you couldn’t play a few of them. I’ve never heard it done like that, but there’s certainly nothing in the way. The last movement, Amphisbaena Retroversa, is the first movement absolutely backwards—with a couple of tiny exceptions because it simply couldn’t be arranged like that. That was symbolic because the Amphisbaena is this animal who not exactly has two heads, but it has teeth in its head and its tail. It was a kind of living and breathing palindrome, you might say, so that was symbolic. It would eat you up with either end, so it should be able to go backwards and forwards. What surprised me, at least in this performance, the running it through backwards was slightly more successful than the original. I don’t know why that should be. It may have been after something like seven or eight hours of recording time, everybody was so happy to get it out of the way, so they simply played it better and said, “Come on, let’s go out for dinner.” [Laughs] I remember this was a long, long session we had at the University of Maryland, but the players were just marvelous, and they wanted to do it over and over and over again to get things exactly right, which they did.

Recordings

|

|

|

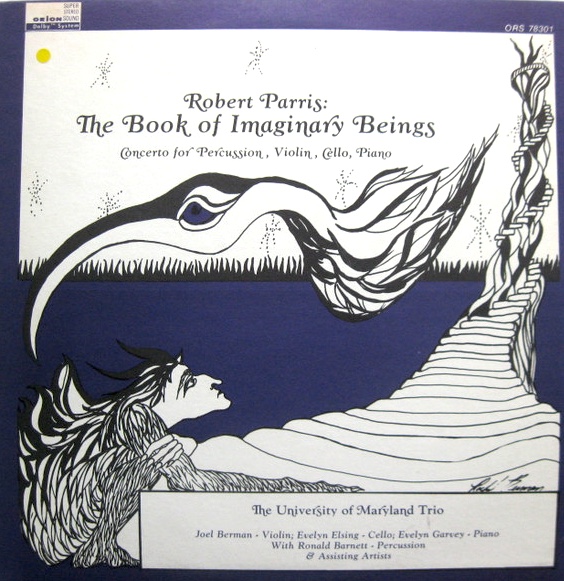

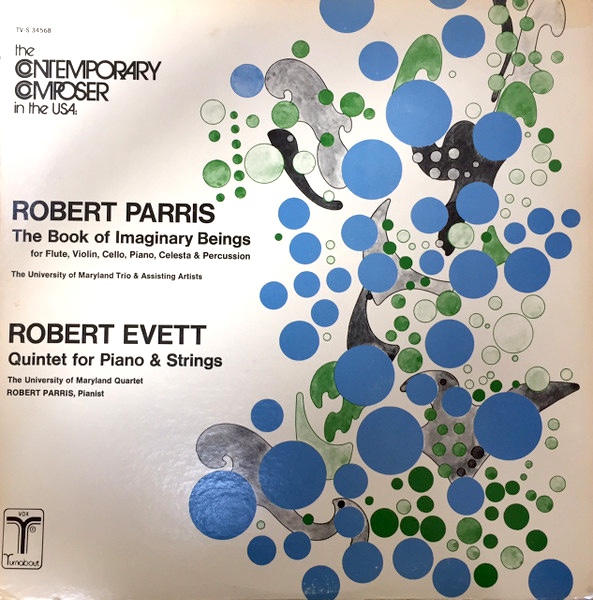

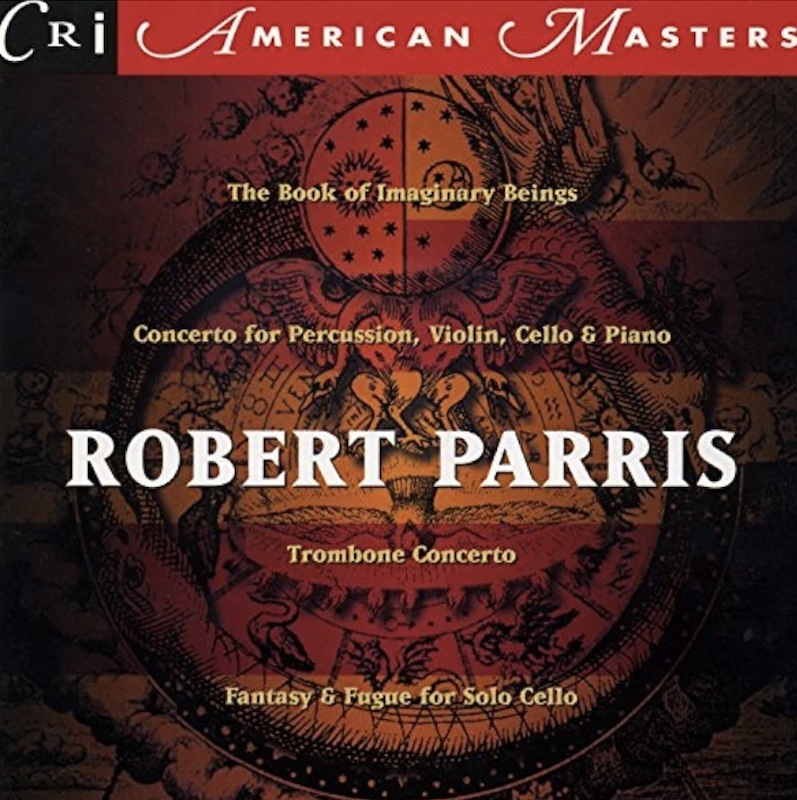

Robert Parris: The Book of Imaginary Beings (1971–72)

Musicians: University of Maryland Trio

LP: The Book of Imaginary Beings. Orion ORS 78301 (1973?)

LP: Parris/Evett: The Book of Imaginary Beings/Quintet for Piano & Strings. VOX/Turnabout TV-S 34568 (1974)

CD: Robert Parris. CRI 792 (1998)

Purchase: CD [New World], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music | New World]

Online: YouTube [Parts I–IV] [Parts V–VIII]

The Book of Imaginary Beings was first performed on 7 May 1972 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. during the American Music Festival under the direction of Richard Bales. The piece was recorded in 1973 at Maryland University’s J. Millard Tawes Fine Arts Auditorium by the “University of Maryland Trio & Assisting Artists.” (The trio consisted of Joel Berman on violin, Evelyn Elsing on cello, and Evelyn Garvey on piano and celesta; the “assisting musicians” included Dorothy Skidmore on flute, William Skidmore on cello, and Ronald Barnett and Thomas Jones on percussion.) Parris’ Book of Imaginary Beings was paired with Colorado composer Robert Evett’s Quintet for Piano & Strings, recorded during the same sessions and released as a “twofer” LP for Vox in 1974. (The recording of Book of Imaginary Beings was also released on LP by Orion, but the year is unrecorded.) In 1991 CRI remastered the recording and reissued it on their all-Parris CD, Robert Parris, now archived by New World Records.

The Book of Imaginary Beings, Part 2

(1983)

For clarinet, violin, viola, cello, and two percussionists

I. The Uroboros—The Harpies—Uroboros Inversus

II. Lilith

III. The Eater of the Dead

IV. The Lemures

In 1983 Robert Parris published The Book of Imaginary Beings (Part 2). Scored for “Mixed instrumental ensemble with 6 to 15 players,” the work is 22 minutes long. To the best of my knowledge, it has never been professionally performed, and it has not been commercially recorded. The score is available through American Composers Alliance, and those with serious intent may inquire at the Robert Parris Archive at the University of Maryland, where the sketches occupy Box 2, Folder 7.

Additional Information

Additional Information

Wikipedia Parris Page

Wikipedia maintains a small page on Robert Parris.

ACA Parris Page

The American Composers Alliance maintains a small Robert Parris page with details on his work.

Parris Interview

Conducted on 22 October 1988 by Bruce Duffie, and the source of the interview excerpt above. Among other things, Parris and Duffie discuss The Book of Imaginary Beings.

Robert Parris Liner Notes

A PDF of the liner notes to the 1999 CRI Robert Parris CD is available through New World Records.

Parris Archival Collection

Located at the University of Maryland, the Robert Parris papers “cover the period from 1952 to 1999; the bulk of the materials date from 1976 to 1999. The collection consists of sketches, drafts, notes and edits, and textual materials used and created during his compositional process.”

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 25 August 2024

Borges Music Page: Borges Music

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com