Borges Review – “Conversations”

- At September 19, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

|

|

|

Jorge Luis Borges: Conversations Vol. 1–3

Interview by Osvaldo Ferrari

Translations by Jason Wilson, Tom Boll, and Anthony Edkins

Seagull Books, 2014–17

“As faith, certainty, dogmas, anathemas, prayers, prohibitions, orders, taboos, tyrannies, wars and glorious deeds astonished the world, a few Greeks acquired, how we will never know, the singular habit of conversation. They questioned, persuaded, disagreed, changed their minds, procrastinated… Distant from them in space and time, this volume is a faint echo of those ancient conversations.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, Prologue to “Conversations, Volume 2.”

Osvaldo Ferrari is an Argentine poet and teacher who organized radio conversations with several famous writers in the 1980s. From March 1984 to October 1985, Ferrari conducted a series of Friday broadcasts with Jorge Luis Borges for LS10 Radio Municipal. Generally lasting fifteen minutes, over one hundred of these dialogues were recorded, many of which were printed in the newspaper Tiempo Argentina.

In 1985, a selection of the Borges-Ferrari dialogues were published as Borges en diálogo. More were collected in 1986 as Libro de diálogos, with Diálogos últimos following in 1987. The dialogues were very popular, and were translated into Italian, Portuguese, French, German, Polish, and Russian across many foreign editions, variations, and reprints. In 1998, Editorial Sudamericana reorganized the interviews into a two-volume set, En diálogo I and En diálogo II. A year later, they collected twenty-eight “outtakes” as Reencuentro diálogos inéditos.

A mainstay of Borges scholarship in the Spanish-speaking world for over thirty years, the Borges-Ferrari dialogues have finally been translated into English by Seagull Books, and are available in three-volume set entitled Conversations. Duplicating the contents of the Sudamericana editions, the set consists of 118 dialogues with individual titles, each reflecting the main topic of conversation. The topics were selected in advance by Osvaldo Ferrari, and following Borges’ own instructions, were not revealed to Borges prior to each interview. Sometimes Borges seems to anticipate Ferrari’s opening question, other times he’s happily surprised, and on rare occasions he’s caught off-guard, vaguely embarrassed or bluntly redirecting the conversation; such as making the scarcely-believable claim, “I can speak about Paz with very little authority. I have read nothing by him. Let’s talk about Reyes.”

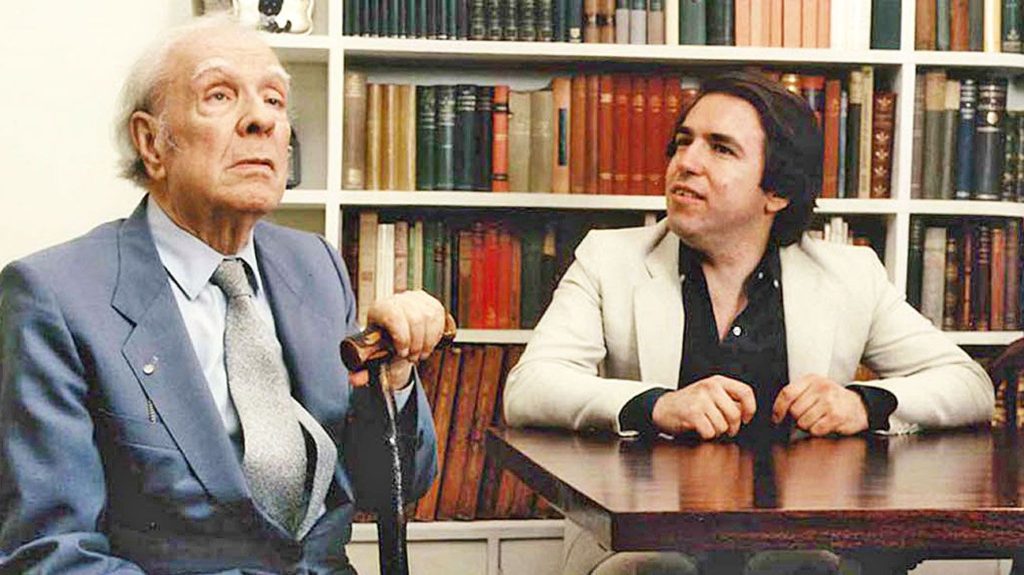

Jorge Luis Borges and Osvaldo Ferrari

Tasked with preparing over a hundred introductory questions, Osvaldo Ferrari proves himself a sharp and determined interviewer. The degree of his erudition, the scope of his questions, and the sensitivity of his responses are essential to the literary quality of these dialogues, and as both participants find their rhythm, their mutual respect warms into genuine friendship. The most obvious antecedent is Richard Burgin’s 1967 interviews with Borges, also published as Conversations and recently included in The Last Interview. In both cases, the reader is struck by the ability of the interviewer to match Borges in depth and breadth of knowledge, and to remain respectful without appearing intimidated.

Ferrari’s list of topics includes numerous familiar subjects—Dante, Swedenborg, Cervantes—along with more offbeat selections such as the I Ching and the moon landing. Borges approaches each conversation with enthusiasm, whether reformulating well-known opinions or surprising Ferrari with fresh insights. Even the most exhausted subjects are reinvigorated by their restless inquisition. After a lifetime of discussing Kafka, it seems astonishing that Borges would have anything left to say, but in “Kafka Could Be a Part of Human Memory,” Ferrari expertly guides Borges into a fascinating conversation about the transformation of literature into cultural mythology.

Ferrari alternates such academic topics with personal questions about Borges’ past, his current travels, and his work habits. Ferrari frequently asks Borges to respond to his own poetry, and quickly learns to parry Borges’ customary modesty to pose deeper questions about meaning and aesthetics. More often than not Ferrari is successful, and his satisfaction is evident when Borges opens up, offering criticisms of his own work and revealing a flinty pride beneath the layers of self-effacement. Indeed, Conversations is at its best when Ferrari explores Borges’ biography, and the dialogues about Macedonio Fernández, Alfonso Reyes, and Ricardo Güiraldes are the highlights of the first volume. Mention of these absent friends and idols engages Borges like no other topic, and his reminiscences contain a warmth rarely seen in his formal writing, whether he’s relating an anecdote about the founding of Proa or the inability for Macedonio Fernández and Xul Solar to recognize each other’s genius. Nor is Borges afraid to critique his predecessors and contemporaries, often with a disarming bluntness. His brutal dismissal of Rubén Darío’s odes and his complaints about Leopoldo Lugones’ ability to kill conversation have the voyeuristic appeal of gossip, a brief peek through the keyhole of a vanished world. (Borges’ frankness towards dead poets makes one wonder what he truly thought of Octavio Paz!)

Sometimes the dialogues move in unexpected directions, especially when their dialectic encounters moments of friction, as may be seen in “On Conjecture.” Here, Ferrari’s attempt to define a “Borgesian genre” is modestly deflected by Borges, who gradually maneuvers the interview into a general discussion about time, mysticism, and an understanding of “intellectual poetry.” Although the resulting dialogue remains interesting, it fails to break new ground, and Borges’ magisterial humility—sometimes charming, sometimes frustrating, and sometimes simply irritating—deprives the reader of a more compelling conversation.

As the dialogues progress, it becomes clear that Borges was preoccupied with particular topics in these final years of his life. The ancient Greeks are mentioned frequently. Argentine literature is firmly seated in the Western canon, which itself is the descendant of “Greek dialogues.” Borges expresses even more disillusionment with politics than usual, and constantly strives to dissociate art from ideology, whether political, cultural, or aesthetic. “Art happens” is a sentiment that recurs throughout the volumes, metaphorically correlated with St. John’s words, “The Spirit blows where it will.” Borges shows his age through more blatant repetitions, sometimes making a joke or retelling an anecdote already shared in a previous conversation. Ferrari deals with such instances with impeccable grace, allowing Borges to finish before redirecting him to a new subject. As Borges himself states, “What else remains for an 85-year-old to do but repeat himself?”

Borges’ advanced age is cause for more than forgivable repetitions; it invests the Borges-Ferrari dialogues with the unspoken gravitas of a final act. As I read them, I kept thinking of Borges’ poem “Límites,” in which the poet enumerates the inexorable reduction of his personal universe. Is this the last time Borges publicly discussed Kafka? The last time he uttered the name of Macedonio Fernández? The last time he read aloud from Yeats? Concluding after the publication of Los Conjurados, in a very real way, the Borges-Ferrari dialogues are Borges’ final work.

In one early dialogue, Borges expresses the astonishment he feels when meeting people who actually interacted with his literary heroes: “I was stunned, because when you think of authors you think of books—somehow, you do not think that the authors of those books were human and that there were people who had met them.” Borges makes this remark to Ferrari with no apparent irony; when Ferrari later states, “It’s said that you are already a living classic,” Borges immediately changes the subject. Fortunately, Ferrari is less dismissive, and implicitly understands the historic opportunity presented by these dialogues. In her song “World Without End,” Laurie Anderson remarks, “When my father died, it was like a whole library had burned down.” Osvaldo Ferrari approaches Borges like a librarian granted one last visit to the stacks. Eight months after their final broadcast, the library doors closed forever.

Additional Information

You may purchase Conversations Volume 1, Volume 2, and Volume 3 at Amazon.com.

Seagull Page

Seagull Books features a page devoted to Conversations.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Date Posted: 19 September 2019

Last Modified: 24 July 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Borges Reviews Page: Borges Reviews

Borges Works Page: Borges Lectures, Conversations & Interviews

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com