Borges Film – Los orilleros

- At October 11, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

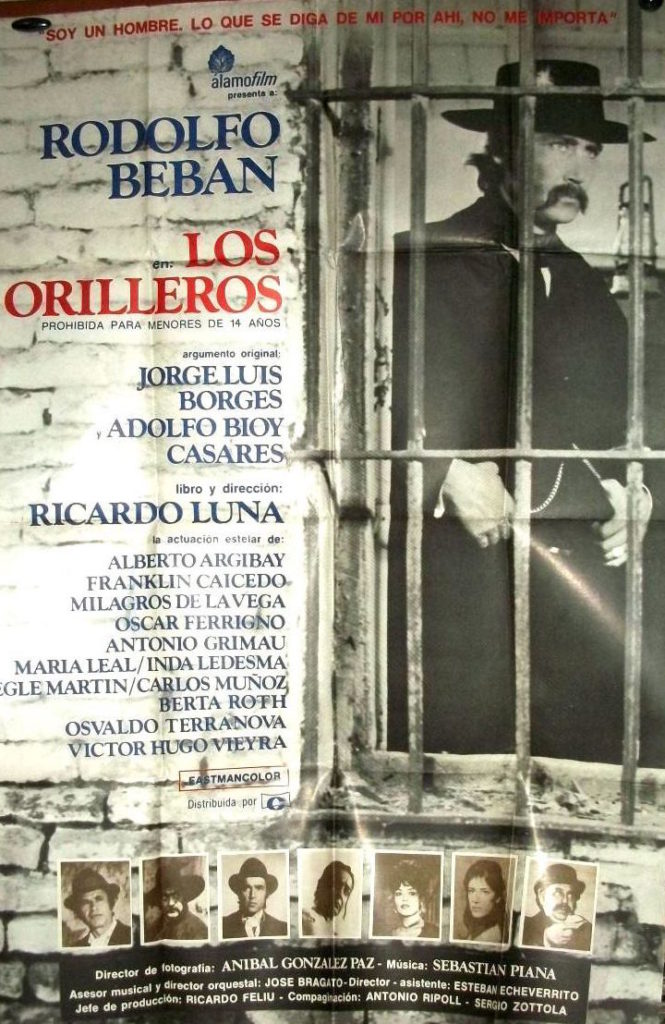

Los orilleros

1975, Argentina, 75 min.

Crew

Directed by Ricardo Luna.

Produced by Ricardo Luna.

Screenplay by Adolfo Bioy Casares, Jorge Luis Borges, and Ricardo Luna.

Music by Sebastián Piana.

Cinematography by Aníbal González Paz.

Cast

Rodolfo Bebán

Alberto Argibay

Franklin Caicedo

Sara Bonet

Milagros de la Vega

Oscar Ferrigno

Antonio Grimau

María Leal

Inda Ledesma

Notes on Translating the Title

The title of this movie is difficult to translate. In Spanish, orilla can mean shore, bank, or edge; in old Buenos Aires, it was the borderland between the city and the countryside, an impoverished suburban region commonly translated as the “outskirts.” The people who lived in la orilla were known as orilleros. (Pronounced “oh-REE-yah” and “oh-REE-yer-os” respectively.)

Rough men who followed a code of honor, orilleros could be outlaws, political henchmen, and knife-fighters; but they were also tradesmen, wagon drivers, and organ grinders. They possessed a rugged sense of refinement, favoring soft black hats with tall crowns, ornate belts, and striped trousers. They played truco, listened to milongas, and danced the tango. As Borges writes in Evaristo Carriego, “They were literally the people.” Depicting them with romantic nostalgia, Borges identifies orilleros as uniquely Argentine—what the gauchos were to the pampa, orilleros were to the barrios.

Los orilleros is about these men, but the title of the film has been notoriously difficult to translate into English. In the Norman Thomas di Giovanni translation of Evaristo Carriego, Los orilleros is given as “On the Outer Edge.” Awkward and ambiguous, this seems worse than Ronald Christ’s “Men from the River Bank,” which has the virtue of being literal, if still inelegant. More commonly, Los orilleros is translated as “Hoodlums,” an infelicitous choice that trades poetry for seediness, and is flawed by the same imprecision as substituting “cowboy” for gaucho. The less-common “Slum Dwellers” has the same problems. Worse still are “The Goldsmiths” and “The Banks,” the lazy products of abusing Google Translate. Personally, I think the best translation is simply “The Outskirts,” but I seem to be in the minority. For the sake of clarity, this page retains the original Spanish title, which has the advantages of being both succinct and correct.

Synopsis

On the outskirts of nineteenth-century Buenos Aires, a melancholy knife-fighter named Julio Morales is drawn to a fateful encounter with Eliseo Rojas, a tyrannical crime boss.

Review

In 1939, Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares wrote a tentative film script called Los orilleros, a tale of an aging knife-fighter reflecting upon his deeds. In a 1958 review of the script, Willis Knapp Jones suggested that “some movie producer” might transform Los orilleros into a “fast-moving crime film with a happy ending.” In 1975, the Argentine actor and choreographer Ricardo Luna became that producer, adapting Borges’ script into a workable screenplay and directing the film himself.

Filmed in Argentina with no input from either Borges or Bioy Casares, Los orilleros comes across as a tame Spaghetti Western, competently made but strangely bloodless—in both senses of the word. Fortunately, it’s well-cast, and the actors do a commendable job with the film’s sparse dialogue. From John Wayne’s smirking bravado in Stagecoach to the squinty-eyed gaze of Clint Eastwood, Westerns have always relied on their actor’s faces to tell an unspoken story, and Los orilleros is filled with close-ups and reaction shots. Luna’s characters smolder, brood, or plead with their eyes, the camera slowly zooming in or pulling back from their faces to suggest troubled souls alone with their thoughts. This pensive solitude gives the film a center of gravity, but unfortunately contributes to a sluggish pace that occasionally risks torpidity. In the hands of a better director, this slow-burn might build tension or establish a sense of place; but any dramatic relief in Los orilleros arrives solely through the mechanics of the script. Even more unfortunate, Luna’s camera is surprisingly disinterested in the textures of the orilla itself. Much of the film takes place indoors, which seems like a missed opportunity.

Lacking the stylized grandeur of Sergio Leone or the dark absurdity of Sergio Corbucci, Los orilleros embraces the sillier tropes of the Spaghetti Western. Women cry hysterically, characters slap each other with comic suddenness, and the robotic death throes of men shot from their horses elicit more chuckles than gasps. These unintentionally funny moments seem out of place for a movie made in the mid-70s, and do little to benefit a film otherwise devoid of humor. The music, too, feels intrusive, melodramatically ladled over some scenes and curiously absent during others. When used appropriately, however, the score is effective, and the Spanish guitars and tango rhythms are a refreshing variation from more traditional Western soundtracks.

Jorge Luis Borges enjoyed Westerns, praising their “epic” qualities in essays and interviews. One day, a director may finally capture Borges’ beloved orilleros, bringing his street-toughs and knife-fighters to life on film the way Astor Piazzolla immortalized them in music. Sadly, Los orilleros is not that film. While it’s interesting to see an Argentine interpretation of a Western—gauchos instead of cowboys, cockfights instead of poker, and those hats!—in the end, the most fascinating thing about Los orilleros is its literary provenance.

Comments

In the final revision of Evaristo Carriego, Borges claims the idea for Los orilleros came from the same source as his inspiration for “Streetcorner Man”—a story he once heard in Palermo about a pair of honor-bound knife-fighters. Written in 1939 in collaboration with Adolfo Bioy Casares, Los orilleros was followed a year later by another joint script, El paraíso de los creyentes (“The Paradise of Believers”). In 1955, Editorial Losada published both scripts as a single book. In a new prologue, Borges and Bioy Casares outlined their inspirations, and detailed their goal to subvert the romantic tropes of Hollywood with modern themes of alienation and the search for identity.

Prologue to Los orilleros/El paraíso de creyentes

By Jorges Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares

Translation by Ronald Christ

The two films that make up this book accommodate—or tried to accommodate—the diverse conventions of filmmaking. We were not drawn into writing them with an eye toward innovations. To take up a genre and to make innovations within it seemed excessively rash to us. Predictable, then, the reader of these pages will find the boy-meets-girl and the happy ending; or, as has already been said in the letter to the “magnificent and most victorious Lord, the Lord Cangrande della Scala,” the “tragicum principium et comicum finem,” the perilous reversal and the happy denouement. Quite possibly, such conventions are feeble. In our own case, however, we have noticed how the films that we recall with the greatest emotion—those by von Sternberg and Lubitsch—respect those conventions to no great disadvantage.

These comedies are also conventional in regard to the characters of the hero and heroine. Julio Morales and Elena Rojas, Rail Anselmi and Irene Cruz, are merely subjects of the action, hollow and pliant forms through which the spectator may pass in order to participate in the incidents. No marked peculiarities stand in the way of one’s identification with these characters. One knows that they are young, it is understood that they are attractive, lacking neither in decency nor valor. Let’s leave psychological complexity to others. In Los orilleros (Men from the River Bank) we leave it for the ill-fated Fermín Soriano; in El paraiso de los creyentes (Paradise for Believers), Kubin.

The first film takes place at the end of the 19th century, the second more or less in our own time. Since local and temporal color exist only as a function of differentiation, it is infinitely probable that these qualities will be more noticeable and effective in the first film. In 1951 we know the differentiating characteristics of 1890, but not what in the future will be those of 1951. On the other hand, the present will never seem as picturesque and affecting as the past.

In El paraiso de los creyentes, the basic motive is love of money; in Los orilleros, emulation. Even though this latter motive suggests morally superior characters, we have resisted the temptation to idealize them, and we believe that neither cruelty nor baseness is lacking in the meeting of the stranger with the boys from Viborita. Of course, both films are romantic, in the same sense that Stevenson’s stories are. They are informed by the love of adventure and, perhaps, a distant echo of epics. In El paraíso de los creyentes, the romantic tone is emphasized as the action progresses. We have decided that the excitement proper to the ending will smooth over certain improbabilities that might not have been accepted at the beginning.

The theme of the search is repeated in both pictures. Perhaps it is not beside the point to note that in ancient books searches were always successful: the Argonauts captured the Golden Fleece and Galahad the Holy Grail. Nowadays, in contrast, we are mysteriously pleased by the notion of an unending search or of a search for something that, once found, has ruinous consequences. K., the surveyor, does not enter the castle, and the white whale destroys the one who eventually finds it. In this sense Los orilleros and El paraíso de los creyentes do not deviate from the norm of our times.

Contrary to Shaw’s opinion that writers ought to flee plots like the plague, we have believed for a long time that a good plot is fundamentally important. The difficulty is that in every complex plot there is something mechanical; the episodes that warrant and explain the action are inevitable and perhaps not spellbinding. Sad to say, the insurance and the ranch in our films correspond to these unfortunate necessities.

As for the language, we have tried to suggest the popular, less by means of vocabulary than by tone and syntax.

In order to make the reading easier, we have shortened or deleted technical terms of mise-en-scène, and we have not retained the double-column format.

Up to this point, reader, the logical justification for our work. Yet there are other justifications, of an emotional nature, and we that these latter were more in force than the former. We suspect that the ultimate reason that moved us to imagine Los orilleros was the desire to fulfill our obligation, in some way, to certain suburbs, to certain nights and dawns, to the oral mythology of courage, and to the brave, humble music commemorated by guitars.

Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares

Buenos Aires, 11 December 1951

Karl Posso discusses their intentions in his essay, “Rethinking Adolfo Bioy Casares”:

In their prologue, Bioy and Borges state that they aim to master convention before they can hope to innovate, thereby defending their recourse to “deleznable” (“contemptible”) but highly successful formulae such as “boy meets girl” and the “happy ending,” and to the orthodox deployment of protagonists who serve the plot as a means of facilitating spectator participation. These screenplays also adhere to genres and narratives well-rehearsed by both writers: detective fiction and the mores of traditionally male society. Boy and Borges claim to be referencing Robert Louis Stevenson and the romantic ideal of the search, but they inflect this—“as befits our age”—in the manner of Herman Melville or Franz Kafka: quests are either infinite or lead to perdition. The scripts are crafted with meticulous attention to the particularities of colloquial language, and include some instructions for cameramen and actors—at times these are remarkably (amusingly) exacting.

Los orilleros are the inhabitants of the space between the city—Buenos Aires—and the countryside. As Beatriz Sarlo discusses in relation to Borges, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was these coarse, violent orillas (“margins”) that popular Argentinian culture was negotiated between urban criollo and gaucho traditions, and later through immigrant customs. Sarlo observes that Borges’s orilleros are the “principled” semi-rural, knife-wielding porteño workers who had all but vanished by the 1920s, though their “vulgar” heirs, the compraditos (loosely: “quarrelsome show-offs”), came to live on through the hyperbolic myths of tango lyrics. Nostalgia and anachronism are also evident in Bioy and Borges’s film script in which the character Julio Morales, in 1948, sets about reflecting on the past and the lost values and valour of neighborhood gangs—labored by Bioy in El sueño de los héroes (filmed by Sergio Renán in 1997.) Amidst much brawling, drinking and banter in taverns, the plot revolves around the felling of the local tyrant, Eliseo Rojas, by a gang hired by his humiliated business partner, Larramendi, who is orchestrating an insurance swindle. The hackneyed theme of honour amongst criminals comes to the fore, and after considerable bloodshed, Morales, who had wanted to test his own bravery by fighting Rojas, ends up falling in love with the latter’s bereaved daughter, Elena. The arch-virtuous Elena declares she loves Morales despite his avenging of her father’s murder in a knife duel.

[From Karl Posso, “Rethinking Adolfo Bioy Casares,” collected in Adolfo Bioy Casares: Borges, Fiction and Art, University of Wales Press, 2012.]

In the 1958 review of Los orilleros/El paraíso de los creyentes quoted above, Willis Knapp Jones simplifies matters considerably, labeling the work as “satirical adventure”:

Two dramatists combine in a couple of movie scenarios of satirical adventure. According to the collaborators, “search” is the common theme. The first is the melodramatic story of a gaucho seeking revenge. In the second, a young man seeks money from gangsters so that his sweetheart will not lose her hacienda. The involved plots come with dialogue, description, and esfumatura, and while not a contribution to the River Plate theater, some movie producer could use them for fast-moving crime films with happy endings.

Alternate Review

Film critic Alonso Díaz de la Vega has a more positive take on Los orilleros, possibly buoyed by a more perfect understanding of the dialogue, which lacks English subtitles. Writing for the Morelia Film Festival, he praises the script for its nuanced take on machismo:

In contrast [to Invasión], Los orilleros is a film from the decade in which it was written originally, that is, the 1930’s. A melodrama about a sort of warlord in the nineteenth century, the film resembles even more Borges’ outlaw short stories and offers a clearer, more genre-oriented narrative. In an interview with the famous literary magazine The Paris Review, Borges explained that westerns seemed to him the contemporary epics. It’s not merely fortuitous that the characters in Invasión watch a western and that Los orilleros seems to be another. Yet there’s a defiance to conventional western morality: even though it’s clear that the warlord Eliseo is a tyrant, there’s a point in the film in which he seems disillusioned with his own machismo. “I thought,” he explains to his daughter, “that only one thing was enough: to be a man,” but separation has taught him otherwise. In that moment of pathos the roles in the film change and the revolutionaries seem crueler than him. It’s a sudden revelation of depth which exposes the minds of Borges and Bioy trying to find, locked in some artifact or in a man, the dimensions of infinity.

De la Vega’s point is well-taken, and Los orilleros can certainly be framed as an early “revisionist” Western, its deconstruction of “conventional western morality” falling between Little Big Man and Unforgiven. Nevertheless, these virtues are present in the original script. Given that Los orilleros was Ricardo Luna’s first and only foray into directing, it’s impossible to know whether he would have pursued Borges’ and Bioy Casares’ ideas any further. Still, like Invasión and Les Autres, Los orilleros is ripe for rediscovery; perhaps a Criterion edition with a remastered picture, English subtitles, and commentary on its historical and literary significance.

Additional Information

Los orilleros

The Garden of Forking Paths has made an MP4 copy of Los orilleros available for downloading. This version used to be on YouTube; don’t expect high quality!

IMDB Page

The Internet Movie Database features a brief profile of Los orilleros.

Wikipedia Page

Wikipedia hosts a brief page on Los orilleros. [Spanish]

The Dimensions of Infinity: The Screenplays of Jorge Luis Borges

A nice piece by Alonso Díaz de la Vega about Invasión and Los orilleros; translated into English and posted on the Morelia Film Festival homepage.

Borges y Bioy Casares en el cine: Los orilleros

Javier de Navascués, 1997. A paper about Los orilleros. [Spanish]

Tragicum Principium et Comicum Finem in Two Cinema Scripts of Jorge Luis Borges

Álvaro Martín Navarro, Letras 2009, vol. 51, n. 80, pp. 164-204. “This essay attempts an exploration of how certain elements of an aesthetics of risky vicissitudes and happy endings are embedded into two scripts written by Jorge Luis Borges with Adolfo Bioy Casares: Los orilleros and El paraíso de los creyentes.” [Spanish]

Bandit Narratives in Latin America

Juan Pablo Dabove’s book boasts a fascinating chapter on Borges’ bandits, and includes a few pages on Los orilleros.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 25 August 2024

Borges Film Page: Borges & Film

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com