Review – People in the Room

- At November 10, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

1

1

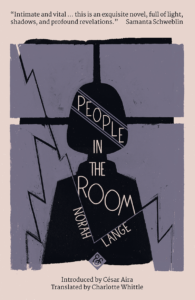

People in the Room

By Nora Lange

And Other Stories, 2018

Review by Gabriel Mesa

The nights and days of Norah Lange pass quiet and bright in a villa that I will not identify with deceitful topographical precision and of which it is enough for me to say that it lies in the deep of the afternoon, next to those large streets of the west on which the dying sun takes pity…. It was in those surroundings that I met Norah, famed for the twin brilliance of her tresses and her proud youth, light on the ground. Light and proud and earnest, like a flag unfurling in the wind, was also her soul.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Norah Lange,” 1925.

The place is Buenos Aires, specifically Avenida Juramento, which still exists today, running in an arc from Avenida Juan B. Justo to Avenida Perón. The time period may be the early 20th century; hansom cabs prowl the streets but houses are beginning to install telephones. A 17 year old girl, both the narrator and the protagonist of the story, sits at the window during a violent storm. In a flash of lightning, she spies the faces of three women sitting and smoking in a drawing room in a house across the street. Unnamed over the course of the narrative, the three will quickly become the subject of the adolescent’s obsession, particularly the eldest, for whom she develops a morbid interest. As the girl falls asleep that night she confesses her fleeting thought “that I would like to see her dead.”

For the narrator, observing the three women in their drawing becomes a nightly vigil, and the possibility that one day they may not be present is a source of compulsive worry:

I watched them for many evenings to reassure myself, and each evening the same fear of losing them, the fear that some word might wound them, that one of them might fall ill or leave on a journey, would leave me tense in my chair, because when they rose from the table they would disappear, leaving the house in darkness; and invariably, though I remembered the previous evening’s unfounded fear, I would be afraid something might happen to them—as I directed them towards recurring fainting fits, unfinished letters—something that might prevent them from coming to the drawing room.

The girl’s obsession is a private matter, of which she tells no one. To avoid questions from her family, she pretends that she is reading as she keeps her evening watch. Her fears begin to take on new forms. She worries that she may not recognize the women if she were to encounter them during the day. She fantasizes that they may be hiding secrets, that they may even have committed a crime—and grows concerned that someone may come to take them away.

One day she believes she sees the women at the post office, posting a telegram and paying in advance for the reply. She thinks that one of their voices sounds like her own. She intercepts the telegram boy as he arrives with the reply. She reads the telegram (“Will come Thursday evening”), reseals it, then rings the bell. The three answer. She gives them the telegram, making up a story about a misdelivery to her house.

That Thursday is a rainy day, and the narrator is at her usual spot by the window, observing the women across the way. A man arrives by horse carriage, enters the house and sits with the women in the drawing room for a spell. As the man leaves, the girl accosts him. “Are they all right, sir? Can I see them?” she asks. She lives in the house across the street, she explains, and was aware they were expecting him. “Tomorrow would be better, miss,” he replies. “It was a painful visit.” We do not hear from him again.

The following day the girl works up her courage and pays the women a visit. They are revealed to be sisters. In the drawing room the four make small talk, share some wine, and the girl explains that she has seen them from across the street. The relationship between the girl and the women now enters a new phase, as she begins to visit them regularly. Even meeting them face-to-face, however, does not abate her morbid leanings; she still watches them from across the street, in the knowledge that the eldest does not “suspect…the special care [she] took in waiting for her to die.” She feels welcome and gets to know them better. She learns of episodes from their past, some of which appear to confirm her suspicion that they keep secret sorrows. She hears of letters burned without reading, of an aborted attempt to commune with dead relatives by table-tapping, of a house on Calle Bulnes where they used to live but of which it is now painful to speak.

At the narrator’s house, her change in behavior has not gone unnoticed. The narrator locks herself in her room to write about the sisters, and when she ignores her family’s insistent knocking matters come to a head. The family believes a change would do her good, and decide she is to spend a few days in Adrogué, a suburb of Buenos Aires where wealthy Argentine families had country homes. The days the narrator spends in Adrogué are pleasant enough, but she cannot speak to anyone about the sisters and begins to have trouble remembering their faces. When it is time to return she is excited and nervous. “I’ll see them tonight,” she thinks. “Everything will go on like before. I’ll visit them tomorrow.” When she arrives she hurries to their house.…

People in the Room was the ninth book and third novel published by the Argentine writer Norah Lange (1905-1972), and is the first of her books to be published in English, in an elegant translation from Charlotte Whittle with an introduction by the noted Argentine author César Aira. Prior to this publication, Lange was best known in the English-speaking world as one of the early muses and love interests of Jorge Luis Borges. Recent English language reviews of People in the Room have tended to sidestep the Lange-Borges connection, which is understandable. After all, with the long overdue publication of her work in English, one would wish to celebrate her writing (in addition to People in the Room she wrote three books of poetry, two more novels, two autobiographical memoirs, and two books of speeches) rather than her relationship with a “great man.” That said, as this review appears on a site devoted to the life and work of Borges, it seems appropriate to spend a little time revisiting her role in his life.

Lange was born in 1905 to a family of Norwegian extraction to whom the Borgeses were related by marriage. A poet from an early age, she was the youngest member of Borges’ group of Argentine Ultraístas, the literary movement he brought back from Spain and hoped to extend to the New World through journals such as Prisma and Proa. She was also the only woman in the group. The Lange house on Calle Tronador was their preferred meeting site and became a favorite destination of Borges, known to his family at the time as “Georgie.” Lange’s beauty and flaming red hair (exotic for Buenos Aires) were renowned, but Borges did not succumb to her enchantments for some time. At first he actually fell in love with Lange’s best friend, Concepción Guerrero, and when her father sought to break off the relationship it was Lange who acted as a go-between, arranging for clandestine meetings between the two lovers at her house. Borges finally broke up with Guerrero in 1924 or 1925, at which time he was becoming closer to Lange. (It is telling that after the break-up Guerrero never spoke to Lange again.) Borges’ growing affection for Lange was reciprocated, at least initially, and their relationship gradually bloomed from friendship to romance. Things were to change, however, at a fateful party in November 1928 held in honor of the author Ricardo Güiraldes, a party which Borges attended with Norah…and which Norah left with another man.

That man was Oliverio Girondo, soon to become Borges’s bȇte noire. Girondo may not be particularly well-known to English-speaking audiences today, but he remains a historically important and influential Argentine poet. It is safe to say that Borges’s reputation has far eclipsed Girondo’s, but at the time they were literary rivals and enmity had already grown between them. Girondo was older than Borges by eight years (which made him older than Lange by fifteen), and not only significantly wealthier but also worldlier. While Borges still lived with his mother, Girondo spent half the year in Europe and was rumored to keep a mistress in Paris. Lange fell head-over-heels for Girondo, breaking poor Georgie’s heart, but her relationship with Girondo was a fractious one. They argued constantly, breaking up and then getting back together several months later (sometimes after a cooling-off trip by Girondo to Europe, possibly to see his mistress). Borges and Lange remained friends and colleagues, and during Girondo’s absence Lange would turn to Borges for solace, albeit strictly of a platonic nature. Borges made several attempts to reignite their old romance (he may even have proposed marriage), but these ultimately went nowhere; to use a term that would only come into vogue 100 years later, Georgie had been “friendzoned.”

Celebrating the release of Lange’s 1933 semi-autobiographical novel, “45 Days and 30 Sailors.” Lange is the mermaid, naturally.

Celebrating the release of Lange’s 1933 semi-autobiographical novel, “45 Days and 30 Sailors.” Lange is the mermaid, naturally.

Lange and Girondo would ultimately marry, in 1943, and by all accounts had a stable relationship until Girondo’s death in 1967. (Lange would follow him five years later.) Although she and Borges remained in intermittent touch over the course of their lives (Girondo he would never forgive), Lange’s rejection was cutting, and Borges biographer Edwin Williamson observes that it “was to be one of the major reversals of his life.” Williamson in fact blames Lange’s rejection for triggering a crisis in Borges’s writing so profound that it made him abandon poetry altogether. Whether one can lay this at the feet of Lange or not, it is certainly true that after publishing “Paseo de Julio” in Criterio in February of 1929, Borges would not publish another poem for 14 years. He had apparently resigned himself to a career as an essayist and reviewer, although we also know that this was not to last. A few years later he would write his first works of fiction, the sketches that would make up Historia Universal de la Infamia, and from there it was but a short step to the classic Ficciones.

In his introduction, Cesar Aira claims that “People in the Room is not a novel to be read for pleasure.” This is a curious statement to introduce a novel one is championing (and Aira is unquestionably a fan), but his point may just be that the novel is not for everyone; that it is slow to reveal its pleasures. At 200 pages, People in the Room is short, but it feels weighty and dense in the reading. The atmosphere is claustrophobic—some of the action takes place in the home of the narrator and some in the house of the sisters, but most of it occurs inside the narrator’s own head. We are witness to her obsessions, her preoccupations, her mental wandering, her fantasies, all centered in some way or another on the figures of the three sisters, particularly the oldest. Lange claimed People in the Room was fundamentally a “spy novel,” but this description doesn’t quite capture the flavor of the book. It is certainly begins as a novel about a type of spying—voyeurism, specifically—but it morphs into a document about obsession of a somewhat dark flavor.

People in the Room may not please readers seeking closure or certainty, but will reward those with a tolerance (or fondness) for ambiguity. The book has an ending but no resolution, answering none of the questions that bedevil the narrator and shedding no light on either the origin or fate of the enigmatic sisters. Even the existence of the three women is in doubt—are they actual individuals living in the house across the street, or do they exist only in the narrator’s mind? I tend to think the latter is the case (as does Aira) but the book does not come out one way or another. Some of the scenes are certainly suggestive, including the one at the telegraph office where the narrator hears her own voice in that of the older sister. On the other hand, there is an early passage where a member of the narrator’s family casually remarks on the three women who live across the street, which certainly argues in favor of their corporeality. Even if one assumes the sisters to be imaginary, however, what would it mean? And what to make of her desire to see the eldest dead? Is the protagonist in the grip of a psychotic episode? Or are the sisters a willful invention by the narrator, a fabrication of which she is aware as she plays an elaborate psychological charade with herself? One need not be constrained by the binary question of whether the sisters are imaginary or made of flesh and blood. Yet another way of reading the novel, one perfectly in keeping with its gothic atmosphere, would introduce a supernatural raison d’ȇtre in which the sisters are actually ghosts or spirits.

Lange’s main inspiration for People in the Room was apparently artistic, a reproduction of the well-known painting of the Brönte sisters by their brother, Branwell Brönte, in which the three sisters sit around a table, staring sternly off to the side.

Curiously, the novel speaks frequently of the sisters as being or having “portraits” (“retratos”), leading to the provocative question of whether the plot is ultimately recursive—is the narrator inventing a story for the three sisters based on a portrait of three women she is observing, mirroring what Lange is doing herself in People in the Room? Treating the novel as a metaphor for artistic creation may be a little stretched, but it’s to the merit of People in the Room that it’s open to multiple types of readings.

In its sly ambiguity, its tense, mysterious atmosphere and its refusal to settle on an explanation for its narrative, People in the Room is a novel that invites not just reading but rereading. I have read it three times now, once on Spanish and twice in English, and remain captivated by the hothouse atmosphere and the unsettled, and unsettling, plot.

Additional Information

People in the Room

You can purchase the book at Amazon.com.

And Other Stories

You can read more about People in the Room on the publisher’s homepage.

Why Was Norah Lange Forgotten?

Heather Cleary of Electric Lit interviews the translator, Charlotte Whittle.

Norah Lange: Finally, ‘Borges’s Muse’ Gets Her Time in the Spotlight

James Reith, The Guardian, 2 August 2018. An incisive article about the neglect of Norah Lange in the world of Latin American translation.

Prólogo a Norah Lange

Borges’ prologue to La calle de la tarde, Lange’s book of poetry published in 1925. The prologue was included in the first printing of Inquiciones, but dropped from later editions.

Author: Gabriel Mesa

Original Upload: 10 November 2019

Last Modified: 12 August 2024

Borges Reviews Page: Borges Reviews

Main Reviews Page: Reviews

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com