Borges Music – Casserley “Edge of Chaos”

- At September 09, 2024

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

The Edge of Chaos

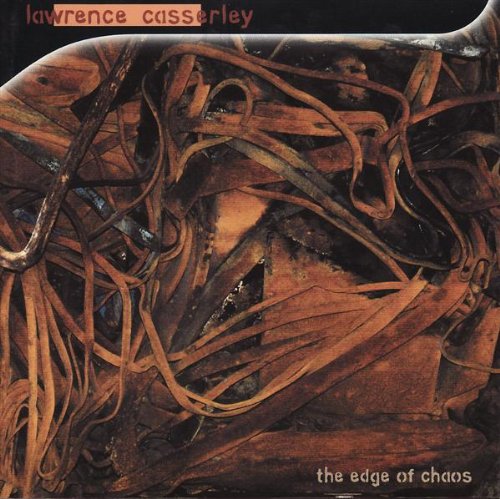

Lawrence Casserley: The Edge of Chaos (2002)

Instruments and Electronics: Lawrence Casserley

CD: Sargasso SCD 28042 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Track Listing

1. Ragnarök (Parable 1) (10:31)

2. Grey Relief In Four Parts (Tàpies 1) (8:41)

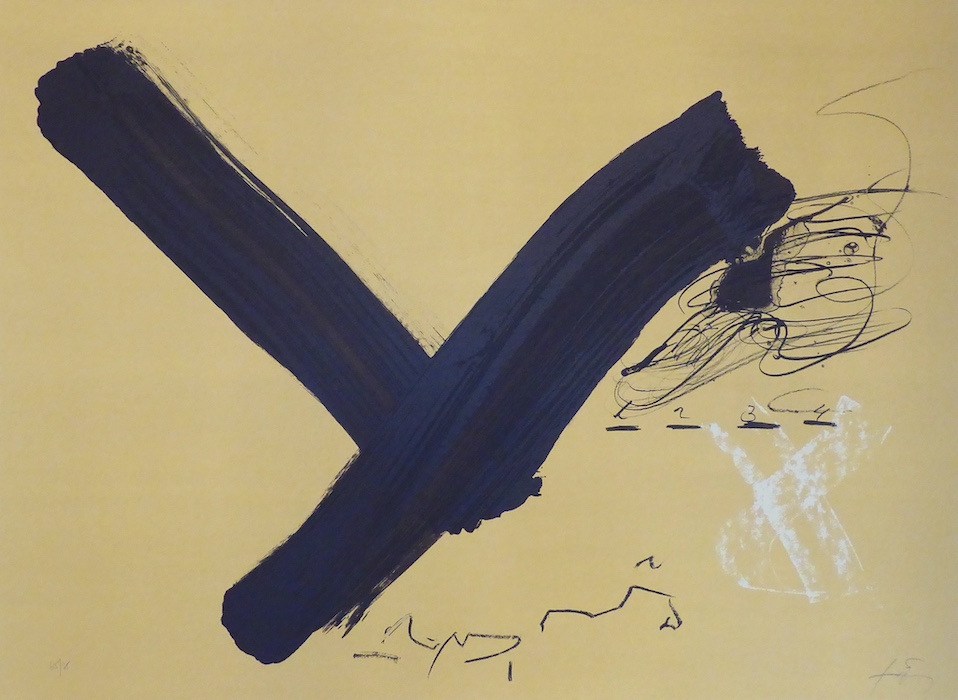

3. “X” (4:18)

4. Infinit (Tàpies 2) (6:14)

5. Cardboard with Knotted Rope (Tàpies 3) (9:36)

6. “Y” (10:02)

7. Brown, Gray and Red Relief / Everything and Nothing (Tàpies 4 / Parable 2) (7:51)

In 2001, Lawrence Casserley was invited to work at the Studio for Electro Instrumental Music in Amsterdam. He decided to record a solo album in honor of his 60th birthday, a thematic sequel to his dense 1999 album, Labyrinths. Like that album, the centerpiece of this project would be Casserley’s Signal Processing Instrument, a computer used to transform traditional acoustic material such as voices and instruments into dramatic new textures. On Labyrinths, the input was provided by soloists playing flute, guitar, and piano. For this new recording, Casserley generated all the sounds himself, from recording his own breathing to playing a battery of gongs, cymbals, metal plates, and “self-built” monochords. These sounds were programmed into the Signal Processing Instrument and the output was recorded on multiple tracks, then mixed into a series of pieces. Casserly arranged the pieces into a coherent sequence and gave them titles derived from two of his favorite artists—Jorge Luis Borges and Antoni Tàpies.

The Edge of Chaos is more sonically homogenous than its predecessor, but also more disorienting. Previously, listeners could find recognizable landmarks in the solo instruments—the flautist Theseus of “Labyrinth,” the plinking guitar of “The Garden of Forking Paths,” the solo piano of “Vista Clara.” On Chaos the initial sound palette is more restricted and more abstract. While the transitions between the individual pieces are not seamless, they’re essentially imperceptible, and the seven tracks flow into each other like the movements of a single work.

Listeners familiar with Casserley’s Labyrinths will find the most musical similarities to that album’s eponymous track. While the central threat of the minotaur is gone, exploring The Edge of Chaos feels like stumbling across new rooms in the House of Asterion. In my review of Labyrinths I suggested that Casserley’s music was a suitable soundtrack to the Navidson House or sunken R’lyeh, and such comparisons feel even more appropriate here. Following the occulted logic of Casserley’s machine, Chaos unfolds a constantly shifting topography; a dense, subterranean soundscape filled with nasty surprises. The walls rumble, the floor groans, and the basement is haunted by the original residents—metals struck, plucked, and twisted into ghostly distortions.

Lawrence Casserley doing his thing…

Lawrence Casserley doing his thing…

The Edge of Chaos opens with “Ragnarök (Parable 1),” named after a prose-poem from Borges’ El hacedor (1960), or “The Maker” (initially translated as Dreamtigers). In the poem, Borges describes a dream in which the old gods return to earth in a parade of majestic forms intended to dazzle our senses and disarm our skepticism. The dreamer/narrator eventually sees through their bankrupt schemes of domination and control. “Ragnarök” ends with one of my favorite Borges sentences, here splendidly translated by Mildred Boyer:

We drew our heavy revolvers—all at once there were revolvers in the dream—and joyously put the Gods to death.

Casserley’s “Ragnarök” makes no attempts to be programmatic music. (Indeed, all the tracks on Chaos were named after they were created.) There’s no procession, no glory, no gunshot. Just a vague sense of dread that reflects the apocalyptic mood of its namesake. Casserley’s gongs and chimes remain intelligible, but their brightness has been digitally redshifted and enmeshed into an undulating mass of sound. “Ragnarök” shimmers and grinds and ebbs and flows; but there’s no rhythm, no resolution—just the menacing aura and desultory hammering of someone groping their way through a migraine. His gods perish slowly, like a fading photograph.

The next few tracks are named after works by the abstract artist Antoni Tàpies, a Catalan painter known for his use of mixed-media. They’re similar in feel to “Ragnarök,” though shorter and less claustrophobic. “Grey Relief In Four Parts” takes the form of a monotonous drone constructed from Casserley’s breathing and subvocalizations, a Lynchian soundtrack that wouldn’t seem out of place in Eraserhead. “X” opens with a metallic slash that decays into a series of diminishing aftershocks—music for a sinking ship. It’s followed by “Infinit,” a buzzing voyage into deep space towards some unknown (and probably unfriendly) source of magnetic interference.

|

|

|

The next piece is named after Tàpies’ “Cardboard with Knotted Rope.” The original artwork uses plywood, rope, cloth, and paint to produce a disturbingly vague suggestion of the Crucifixion, a Renaissance painting recomposed through castaway materials. Casserley uses similar materials to generate his acoustic sounds—handmade monochords consisting of wooden boards fixed with individual strings. Amplified and distorted by the Signal Processing Instrument, these harmless zithers are transformed into an industrial nightmare. A junkyard unpacking itself in slow motion, the track has the most dynamic range of anything else on Chaos, and contains some of its most interesting sonic textures.

“Cardboard” is followed by “Y,” a metallic soundscape punctuated by trembling gongs, cascading bells, and spectral murmurs. It’s the closest the album gets to traditional “haunted house” music.

The album concludes with an eight-minute piece that splits the difference between Tàpies and Borges: “Brown, Gray and Red Relief / Everything and Nothing.” Returning to the claustrophobia of “Ragnarök,” the track acquires a shrill insistency as it rumbles towards its conclusion, a “controlled delirium” preparing the way for the whirlwind.

The Edge of Chaos is a difficult album to categorize. Fans of electronic music may find it too atonal, fans of industrial may find it too avant-garde, and fans of Stockhausen—well who knows what Stockhausen fans are going to like! It’s probably best classified as “experimental music,” filed somewhere between Nurse with Wound and Hauntology. Like the work of Borges and Tàpies, Casserley’s music frustrates labels, creating its own precursors and becoming its own genre. I definitely recommend headphones and a high volume—and keep the lights on.

Liner Notes

By Lawrence Casserley

The Edge of Chaos

Sargasso, 2002

The ideas of Journey and Transformation have been constants in my work for many years, and since, more than thirty years ago, I began to work with electronic sound, these ideas have become fused into one entity. Each sound is taken on a journey of transformation in which new aspects of itself are discovered; and so the listener is also led on a journey of discovery.

There is also another kind of journey, my own personal journey to create an electronic instrument that enables me to create spontaneously the sound transformations that my music requires. Recently I have developed a computer processing instrument that begins to answer these needs—the journey is still going on…

This journey is documented in several CDs, particularly Solar Wind (Touch—TO:35) with Evan Parker and Dividuality (Maya Recordings—MCDO101) with Evan Parker and Barry Guy. In 1997 I was invited by STEIM (Studio for Electro Instrumental Music) in Amsterdam to realise a project with Evan and Barry; for three weeks I worked at STEIM creating the prototype of my Signal Processing Instrument and playing it with my collaborators. Solar Wind was recorded there, and Dividuality was recorded at Gateway Studios in London shortly afterwards. Subsequently I have made many performances and recordings with this instrument. An important characteristic of all these recordings is that I am always processing (transforming) the sounds made by other musicians—my Signal Processing Instrument makes no sounds itself, only transforms sounds played into it.

Even my pre-composed work, as represented by Labyrinths (Sargasso—SCD28030), involves close collaboration with other musicians. Collaboration has always been at the centre of my work. Again and again I have found that working with other artists—musicians, painters, poets, whatever—has stimulated the most creative responses. Even when I wasn’t collaborating directly, ideas from other art forms, particularly painting and literature, stimulated me.

So, when setting out to create a solo CD, it was not surprising that I took with me two of my favourite inspirations, the writing of Jorge Luis Borges and the painting of Antoni Tàpies. My other inspiration was the beautiful city of Amsterdam. Once again I was invited to work at STEIM, this time to spend three weeks on my own in the studio. I took my collection of Chinese gongs and cymbals, a set of metal plates, my self-built monochords, a complex setup of microphones and mixers, my Signal Processing Instrument and a computer multi-track recording system. This would be far too complex for a concert tour, but with three weeks in the studio a two day setup was no problem.

I rarely use all these resources together. For example, “Grey Relief in Four Parts” uses only vocal sounds, including breath; “X” uses only scraped percussion; and “Cardboard with Knotted Rope” uses only monochords. Without the stimulus of other players, I wanted a large range of source material, but I also wanted each piece to have its own special character. Also the source sounds are only heard occasionally; the emphasis is always on the transformations.

Strangely perhaps, the original impetus for this project came from a review of Solar Wind by Jim Denley in Resonance magazine. I was struck by this review not because it was good (which is always pleasant!), but because it seemed to articulate so exactly some of my own thoughts—this man had seen into my soul! One particular reference to the “gritty dirt of chaos” was the piece of grit that started the pearl of a new idea. It reminded me of the postcard text of Peter Altenberg set by Alban Berg in his “Altenberg Lieder” of 1912. “Over the edge of everything you look…” conjures a vision of primaeval chaos and the topological cusp on which we all sit; like standing on the top of a cliff. Borges’s “Garden of Forking Paths” presents another aspect, where all futures are possible. I see yet another aspect of this in some of Tàpies’s work; particularly the courage with which he uses his materials, allowing them to crack and split, to develop a language of their own, beyond the edge of his direction. He tickles the edge of chaos.

I see here a parallel with the way my Signal Processing Instrument works; frequently I set processes in motion, which then develop destinies of their own. I send a sound on a journey whose precise route through the garden of forking paths is now in the hands of the process. It is then up to me to respond to and interact with this new life form. The piece “Y” was made like this; I made no attempt to alter the process once it had begun; rather responded to what it was telling me to play. This balance between directedness and acceptance is an essential aspect of the journey, and of the music on this CD.

In borrowing some of my titles from Borges and Tàpies I make no attempt to “interpret” those works. In almost every instance the association of a piece of music with a particular title came after I had played the music. It is more that I see connections between all these things, and it is this connectedness that is the consequence of the chaos. Significantly, the one time I actually set out to make a piece called “Everything and Nothing”, planned as the final track, I was dissatisfied with the result. It was only much later that I realised that the piece I had called “Brown, Grey and Red Relief” was not only the right conclusion to the CD, it was also a fusion of the different strands, and it might even be called “Z” as well.

I would like to express my special thanks to all the people at STEIM who helped me, most particularly Nico Bes, Joel Ryan and Michel Waisvisz. I would also like to thank all those others, too many to name, who encouraged me in this project.

—Lawrence Casserley, December, 2001

Borges: “Ragnarök”

In dreams, writes Coleridge, images represent the sensations we think they cause: we do not feel horror because we are threatened by a sphinx; we dream of a sphinx in order to explain the horror we feel. If this is so, how could a mere chronicle of the shapes that that night’s dream took communicate the bewilderment, the exaltation, the alarm, the menace, and the jubilation that wove it together? None the less, I shall attempt that chronicle. Perhaps the fact that a single scene united the dream will remove or alleviate the essential difficulty.

The scene was the College of Philosophy and Letters, the hour twilight. As usual in dreams, everything was a little different; a slight enlargement altered things. We were electing officers. I was talking with Pedro Henriquez Ureña, who in the waking world has been dead for many years. Suddenly we were interrupted by a clamor as of a demonstration or a band of street musicians. Howls, both animal and human, rose from below. A voice cried out, “Here they come!” and then, “The Gods! The Gods!” Four or five fellows emerged from the mob and took over the platform of the assembly hall. We all applauded, weeping: these were the Gods, returning after a centuries-long exile. Exalted by the platform, their heads thrown back and their chests out, they haughtily received our homage.

One was holding a branch which conformed, no doubt, to the simple botany of dreams; another, in a broad gesture, held out his hand—a claw; one of the faces of Janus looked suspiciously at the curved beak of Thoth. Goaded perhaps by our applause, one, I do not know which, broke out in a victorious and incredibly bitter cackle, half gargle, half whistle. From that moment on, things changed. It all began with the suspicion, perhaps exaggerated, that the Gods could not talk. Centuries of brutish and bloodthirsty life had atrophied whatever there had been of the human in them. Islam’s moon and Rome’s cross had dealt implacably with those fugitives. Low foreheads, yellow teeth, sparse mustaches like a mulatto’s or a Chinaman’s, and thick bestial lips bespoke the degeneration of the Olympian lineage. Their garments were less suited to decorous, decent poverty than to the evil sumptuousness of the gambling dens and bawdy houses of Below. In the buttonhole of one bled a red carnation; beneath the tight-fitting jacket of another bulged the form of a dagger.

Suddenly we felt they were playing their last card, that they were crafty, ignorant, and cruel as old beasts of prey, and that if we allowed ourselves to be won over by fear or pity, they would end by destroying us.

We drew our heavy revolvers—all at once there were revolvers in the dream—and joyously put the Gods to death.

—Translation by Mildred Boyer

Borges: “Everything and Nothing”

There was no one inside him, nothing but a trace of chill, a dream dreamt by no one else behind the face that looks like no other face (even in the bad paintings of the period) and the abundant, whimsical, impassioned words. He started out assuming that everyone was just like him; the puzzlement of a friend to whom he had confided a little of his emptiness revealed his error and left him with the lasting impression that the individual should not diverge from the species. At one time he thought he could find a cure for his ailment in books and accordingly learned the “small Latin and less Greek” to which a contemporary later referred. He next decided that what he was looking for might be found in the practice of one of humanity’s more elemental rituals: he allowed Anne Hathaway to initiate him over the course of a long June afternoon. In his twenties he went to London. He had become instinctively adept at pretending to be somebody, so that no one would suspect he was in fact nobody. In London he discovered the profession for which he was destined, that of the actor who stands on a stage and pretends to be someone else in front of a group of people who pretend to take him for that other person. Theatrical work brought him rare happiness, possibly the first he had ever known–but when the last line had been applauded and the last corpse removed from the stage, the odious shadow of unreality fell over him again: he ceased being Ferrex or Tamburlaine and went back to being nobody. Hard pressed, he took to making up other heroes, other tragic tales. While his body fulfilled its bodily destiny in the taverns and brothels of London, the soul inside it belonged to Caesar who paid no heed to the oracle’s warnings adn Juliet who hated skylarks and Macbeth in conversation, on the heath, with witches who were also the Fates. No one was as many men as this man: like the Egyptian Proteus, he used up the forms of all creatures. Every now and then he would tuck a confession into some hidden corner of his work, certain that no one would spot it. Richard states that he plays many roles in one, and Iago makes the odd claim: “I am not what I am.” The fundamental identity of existing, dreaming, and acting inspired him to write famous lines.

For twenty years he kept up this controlled delirium. Then one morning he was overcome by the tedium and horror of being all those kings who died by the sword and all those thwarted lovers who came together and broke apart and melodiously suffered. That very day he decided to sell his troupe. Before the week was out he had returned to his hometown: there he reclaimed the trees and the river of his youth without tying them to the other selves that his muse had sung, decked out in mythological allusion and latinate words. He had to be somebody, and so he became a retired impresario who dabbled in money-lending, lawsuits, and petty usury. It was as this character that he wrote the rather dry last will and testament with which we are familiar, having purposefully expunged from it every trace of emotion and every literary flourish. When friends visited him from London, he went back to playing the role of poet for their benefit.

The story goes that shortly before or after his death, when he found himself in the presence of God, he said: “I who have been so many men in vain want to be one man only, myself.” The voice of God answered him out of a whirlwind: “Neither am I what I am. I dreamed the world the way you dreamt your plays, dear Shakespeare. You are one of the shapes of my dreams: like me, you are everything and nothing.”

—Translation by Kenneth Krabbenhoft

Additional Information

Additional Information

Lawrence Casserley Homepage

Casserley’s own web site offers information about his life and works.

Signal Processing Instrument

Lawrence Casserley’s paper on his SPI for the Journal of Electroacoustic Music.

Sargasso Records

The page for The Edge of Chaos at Sargasso Records.

Lawrence Casserley Borges-Related Works

Lawrence Casserley Main Page

Return to the Garden of Forking Path’s Lawrence Casserley profile.

Solar Wind (1997)

A joint project by Lawrence Casserley and British saxophonist Evan Parker, Solar Wind bears a quotation from Borges’ “The Circular Ruins.” [Link takes you to Bandcamp]

Labyrinths (1999)

This album collects four pieces structured as “musical labyrinths,” three of which were directly inspired by the works of Borges.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Image Credits: X, Cardboard with Knotted Rope, and Y by Antoni Tàpies.

Last Modified: 9 September 2024

Borges Music Page: Borges Music

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com