Borges Film – Performance

- At November 02, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

1

1

Performance

You do not have to be a drug addict, pederast, sadomasochist or nitwit to enjoy “Performance,” but being one or more of those things would help.

—John Simon, “New York Times,” 1970

1970, U.K., 105 min.

Warner Archive Collection: DVD | Blu-ray | Amazon Prime

Crew

Directed by Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell.

Produced by Donald Cammell and Sanford Lieberson.

Screenplay by Donald Cammell.

Cinematography by Nicolas Roeg.

Music by Jack Nitzsche.

Cast

Mick Jagger – Turner

James Fox – Chas

Anita Pallenberg – Pherber

Michèle Breton – Lucy

Ann Sidney – Dana

John Bindon – Moody

Stanley Meadows – Rosebloom

Allan Cuthbertson – The Lawyer

Anthony Morton – Dennis

Johnny Shannon – Harry Flowers

Anthony Valentine – Joey Maddocks

Kenneth Colley – Tony Farrell

John Sterland – The Chauffeur

Synopsis

It’s the late 1960s in Swinging London. The gangster Chas has a reputation as a “performer,” a reliable earner and dutiful soldier. After crossing his boss, a criminal overlord named Mr. Flowers, Chas is forced into hiding. Hearing of a spare room in Notting Hill, Chas finds himself in a crumbling mansion inhabited by a vampiric threesome—a declining rock star named Turner, his beguiling girlfriend Pherber, and their young lover Lucy. As Chas is lured deeper into their world of sex and drugs, he begins to lose hold on his sanity. Meanwhile, his former colleagues are closing in, precipitating a clash between two parallel realities.

Comments

In Borges’ short story “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a character makes an exclamation that’s become one of Borges’ most famous ideas: “the book and the labyrinth were one and the same.” In Performance, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg create a film that is also a labyrinth, one in which Theseus finds his way to the lair of the Minotaur, only to discover they are also “one and the same.”

The film opens on Chas, a London gangster going about the daily brutalities of his profession. A classic anti-hero, the charismatic but violent Chas is played by James Fox, a former soldier whose face is a collection of sharp angles. Right from the beginning, we know that something is off. Filmed using cinematic cut-ups, events are presented out of sequence, and it’s difficult to construct a coherent narrative until well into the film’s first half-hour. There’s passionate sex, intimidation, frequent driving, and criminal board meetings—is all this happening on the same day? There’s also intrusive jump-cuts and abrupt shifts in cinematography, like irruptions from a different movie. Less obvious are brief flashes of Chas played by Mick Jagger, subliminal signals suggesting that not everything is what it seems.

Placing a personal vendetta above his employer’s orders, Chas betrays his gang and is forced into hiding. Adopting a ridiculous disguise that foreshadows Roeg’s orange-haired David Bowie, he finds his way to the Notting Hill home of Turner, a Byronic rock star played by a gloriously young Mick Jagger. His muse having deserted him, Turner has retreated from the spotlights, sharing his brokedown palace with a worldly seductress named Pherber and a waifish ingénue named Lucy, played by Anita Pallenberg and Michèle Breton respectively. Ensconced in a crumbing labyrinth of velvet drapes, gilded mirrors, and monstrously large bathtubs, the ménage-à-trois inhabits a decadent, pre-Raphaelite fantasy, like Dracula and his brides.

Accustomed to being in control, Chas discovers that he’s surprisingly out of his depth among the debauched trio, who willfully dissolve his hard edges in scented bathwater and magic mushrooms. But this is no simple tale of Odysseus among the Lotus-Eaters, or Jonathan Harker at Castle Dracula; in Performance, the vampiric exchange is mutual. Turner finds himself increasingly drawn to the gangster’s world of suits, guns, and power, seeing Chas as a fresh “demon” to replace his vanished muse. The pair circle each other like wary predators, two egomaniacal performers spiraling a mutual gravitational core. Their scenes together are the best in the movie, charged with a sexual tension more autoerotic than homoerotic, a cynical narcissism underscored by the abundant presence of mirrors, nymphs, and flowers. (Or in this case, bright red caps of fly agaric!)

Eventually it comes time for Chas to depart the mansion and escape London. His final night with the trio is a carnivalesque excursion into derangement, and the film gleefully unravels in a confusion of sex, drugs, and rock and roll—quite literally. Like a Thomas Pynchon narrative, Performance suddenly beaks into song, and the climax of the film arrives as a Mick Jagger music video! Ostensibly still “Turner,” Jagger is styled as Chas, and relives moments from the gangster’s life while singing “Memo from Turner,” a brilliant Stones outtake from Beggar’s Banquet. Meanwhile, sporting make-up and a wig, Chas has transformed into Turner, now sexually linked to the androgynous Lucy—with Breton occasionally replaced by flashes of Jagger!

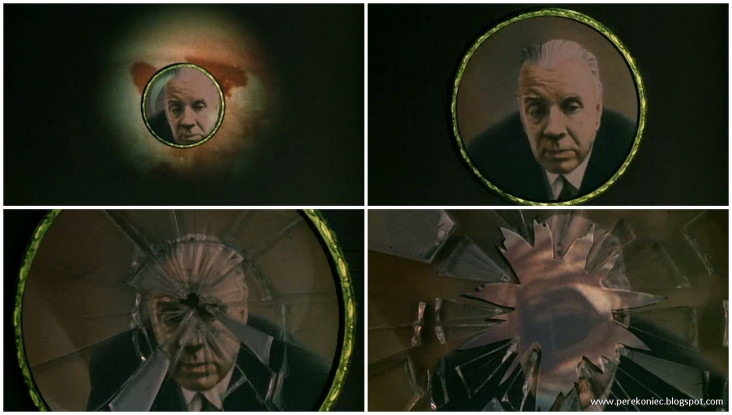

Here at the center of the maze, everyone seems to be everyone else; or as Borges wrote in his review of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, “we may imagine a pantheistic film whose numerous characters finally resolve into One, who is everlasting.” But this is still a labyrinth, and in the end Theseus must slay the Minotaur; although it’s not entirely clear whether the act is murder, suicide, or ritual magic. This paradox is visually symbolized by a brief glimpse of Borges, his face superimposed over the moment of death/transformation itself.

We’ve got to go much further—out.

—Pherber

The Story of Performance

Performance is a trip through a psychedelic funhouse where mirror images blur together in uneasy couplings: sex and death, reason and madness, beauty and ugliness. Mick Jagger is the perfect embodiment of these dichotomous tensions. His performance is mesmerizing, trading on Jagger’s real-world celebrity and fueled by the legendary affair he was having with costar Anita Pallenberg, who was dating Keith Richards at the time. One of the most controversial movies of the sixties, Performance was completed in 1968, but the studio was shocked by its frank depiction of drug use and its pornographic sex. The film was declared “unreleasable” and confined to the shelves for eighteen months. In 1970, it was re-edited and quietly distributed with an X rating.

By now, a casual reader may be wondering: an X-rated Borges film starring Mick Jagger? What the fuck? And that is an entirely reasonable response; Borges is hardly an erotic writer, and his fondness for rock music arrived late in life. Performance was originally intended to be a lighthearted gangster film set in London’s Swinging Sixties—Warner Brothers believed they were getting a Rolling Stones version of A Hard Day’s Night! So what happened?

Well, Donald Cammell happened.

I need a bohemian atmosphere!

—Chas

The Writer

A bohemian filmmaker whose father wrote a biography of Aleister Crowley, Cammell claimed that his childhood was “filled with magicians, metaphysicians, spiritualists and demons.” At the age of sixteen, he was awarded a scholarship to the Royal Academy to pursue fine arts. Cammell spent time in Italy as a “society painter,” then moved to New York City, where he developed a reputation for painting sensuous nudes. Relocating to Paris, he turned his talents to cinema.

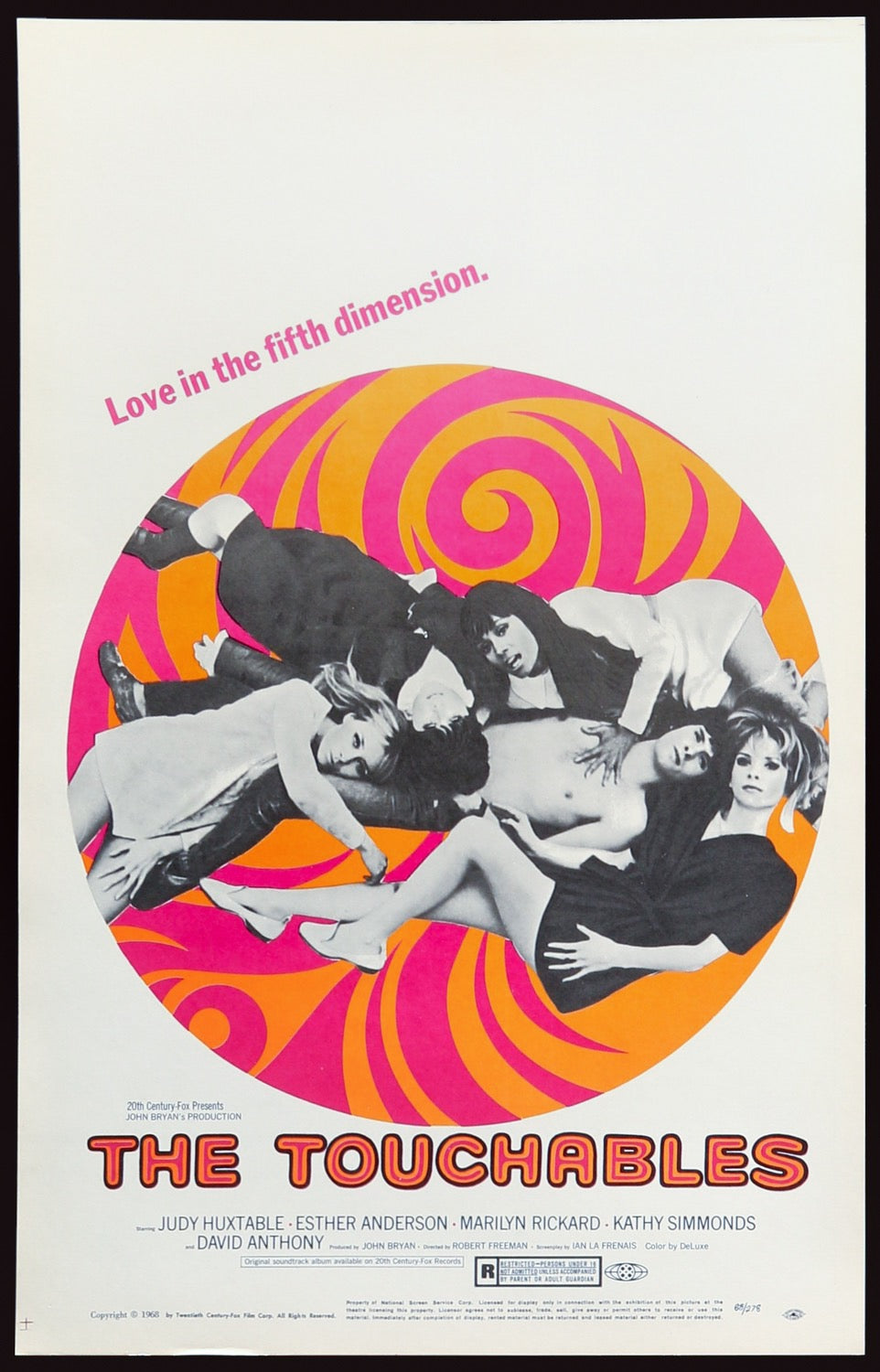

Donald Cammell’s first project was a caper comedy called Duffy, starring James Fox as a playboy trying to rob his millionaire father. This was followed by The Touchables, a mod gangster film directed by Robert Freedman, a photographer known for his Beatles album covers. Based on a story by Cammell, its plot is deftly summarized by Wikipedia: “In Swinging London, four girls decide to kidnap their pop idol and hold him hostage in a giant plastic dome in the countryside. His manager tries desperately to find him, as does a wrestler and an upper class London gangster. However it becomes clear that the young man does not want to be freed from his glamorous captors.”

Love in the fifth dimension, baby!

Although it would become a minor cult classic, The Touchables was initially unsuccessful, dismissed by the New York Times as “sort of fidgety mod pornography, which uses the advertising convention for eroticism—cutting abruptly from teasing sex scenes to gadgetry, in this case pinball machines, trampolines and odd items of furniture and clothing.” Cammell was undaunted, and decided to rework the film’s themes into a new and better movie tentatively named The Performers, a film that would feature an on-the-lam gangster and a dissolute rock star. He already had his female lead, fashionista Anita Pallenberg, the German-Italian model who had starred as the Black Queen in Barbarella.

At this point, an historical accounting of events must venture into the fog of speculation and rumor which perpetually enshrouds the making of Performance. Some accounts contend that Donald Cammell and his girlfriend, the American model Deborah Dixon, met Anita Pallenberg in St. Tropez. They conducted a brief ménage-à-trois while working on the screenplay. Other sources suggest that Cammell and Dixon actually met Michèle Breton in St. Tropez, the French teenager who plays Lucy. A runaway from a small town in Brittany, Breton was drawn into the couple’s sexual orbit, only to be callously discarded after filming wrapped. In any event, Cammell soon had a rough draft of the screenplay, with his friend Marlon Brando tentatively cast as the gangster.

Through his relationship with Pallenberg, Cammell became friends with the Rolling Stones; Pallenberg had just broken up with Brian Jones and was now dating Keith Richards. Cammell believed that Mick Jagger was perfect for his louche rock star. After seeing Roger Corman’s Masque of the Red Death, he convinced cinematographer Nicolas Roeg to come onboard as co-director, and The Performers became Performance. Although Marlon Brando withdrew from the project, Warner Brothers gave the film a green light—a Swinging Sixties romp featuring Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg? Sign me up!

Anita Pallenberg and Donald Cammell

The only performance that makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.

—Turner

The Filming

Enter Jorge Luis Borges. As Cammell’s project developed, he discovered Borges, and began reworking his script accordingly. No longer a Beatlesque romp, Performance was given a darker edge, an exploration of Borgesian themes of identity, duality, and the annihilation of the self. Cammell was additionally influenced by Antoine Artaud, Vladimir Nabokov, and William S. Burroughs, particularly the “cut-up” method of narrative assembly he pioneered with Brion Gysin. His co-director Nicolas Roeg was also eager to try something more experimental.

The set of Performance quickly took on a life of its own, a promiscuous den of iniquity where sex and drugs were commonplace. Heroin was rampant, and everyone seemed to be sleeping with everyone else. As Mick Jagger’s girlfriend Marianne Faithfull remarked in her autobiography, the set was “a psychosexual laboratory…a seething cauldron of diabolical ingredients: drugs, incestuous sexual relationships, role reversals, art and life all whipped together into a bitch’s brew.” Disturbed by the bad vibes, she departed for Ireland. Even Brando’s replacement contributed his own strange energy. Having starred in Duffy and befriended Mick Jagger, James Fox and his girlfriend were supposedly on intimate terms with Jagger and Faithfull.

Anita Pallenberg, Michèle Breton, and Mick Jagger

Anita Pallenberg, Michèle Breton, and Mick Jagger

As filming proceeded, Keith Richard’s relationship with Mick Jagger took one of its periodic sour turns. Hearing that Jagger and Pallenberg’s sex scenes were “unsimulated,” Richards blew a fuse and began stalking the set. (Although Jagger remains ambiguous about the alleged affair and Pallenberg denies it, Richards insists it happened, and Fox claims he came across Jagger and Pallenberg having sex in the dressing room.) This fracture between the Glimmer Twins removed the Rolling Stones from the table, and Performance became exclusively a Mick Jagger vehicle. (The realistic sex scenes were destined for controversy with or without the affair, and Performance contains one of the most memorable—and genuinely erotic—threesomes in cinema. This controversy would be repeated in 1973 for Roeg’s Don’t Look Now, which is also rumored to feature authentic sex.)

When the film was finally screened for Warner Brothers, they were understandably appalled. This was not another Hard Day’s Night! This was an experimental film saturated by sex, drugs, and violence, mired in controversy, and making obscure allusions to a little-known Argentine fabulist. Even after the film was edited to include more Mick Jagger, Performance was a flop, drawing harsh reviews and only winning a single award—and that was bestowed by an Amsterdam pornography festival!

You’re a comical little geezer. You’ll look funny when you’re fifty.

—Chas

Aftermath

Time has been kinder to Performance than its studio executives and contemporary audiences. Like Gimme Shelter, another 1970 film starring Mick Jagger, Performance is widely recognized as a landmark film capturing the disillusionment and failure of the sixties. Also like Altamont, it left a wake of destruction in its passage. Although Mick Jagger seemed to thrive—how very Turner of him!—Anita Pallenberg and Michèle Breton both succumbed to heroin addiction, and James Fox had a nervous breakdown before joining a Christian cult. Keith Richards never forgave Donald Cammell for meddling in his affairs, excoriating the director in his autobiography.

After Cammell made edits to Performance without Roeg’s consent, the two directors had a falling out. Nicolas Roeg went on to direct a string of modern classics including Walkabout, Don’t Look Now, and The Man Who Fell to Earth, starring David Bowie as a stranded alien. Donald Cammell also continued to make movies, but his projects frequently failed before they could enter production. His most famous movie after Performance was Demon Seed, a surreal horror film about an evil computer that tries to impregnate Julie Christie.

In 1996, Donald Cammell shot himself in the head. According to popular legend, he asked his wife to bring a mirror so he could watch himself die. His last words were, “Can you see the picture of Borges?”

They would not have allowed such things to happen to me in the sanitarium, he thought.

—Turner, reading from Borges’ “The South”

Borges Influence

The image of Borges glimpsed at the conclusion of Performance is not the only Borges reference in the film. Indeed, Donald Cammell canonized Borges as the patron saint of Performance, and his presence hovers over the entire production. Both Chas and Turner are shown reading Personal Anthology, the collection of stories published the year Performance was filmed. Turner mentions “Orbis Tertius” during his initial interview of Chas, and later reads a passage from “The South” out loud. Turner’s entire mansion is a labyrinth, its layout deliberately obscure and the number of rooms uncertain; even the tilework above the celebrated bathtub is patterned as a maze. Mirrors, another Borges obsession, play an equally important role in Performance. They appear in every critical scene; merging characters into hermaphrodites, reflecting the hidden and occulted, or just abominably increasing the number of men. And to a modern viewer familiar with Donald Cammell’s suicide, it’s impossible not to think of the director’s final words—“Can you see the picture of Borges?” Apocryphal or not, they remain part of the mythology. Whether he was speaking of the image imbedded in Turner’s brain or something more personal is a mystery; but with its psychedelic drugs, ritual magic, and threesomes, Performance was already functioning as semi-mythical autobiography. Cammell’s final act haunts the film, infusing Performance with the enigma of suicide and the darkness of personal prophecy.

More on Performance

Below are excerpts of published works that that highlight the Borgesian influence on Performance. Spoilers abound.

Interview Excerpt with Daily Cinema

Donald Cammell: Nic and I had been friends for years. We both read the same books, which to my mind is more important than seeing the same films. Our initial inspiration came from Borges and Vladimir Nabokov’s Despair, a story which makes a kind of ecstatic exploration of a character’s fatal encounter with his double or alter ego—as in Performance. I was fascinated by the idea of murder which might also be suicide.

Interview with David Del Valle

David Del Valle: At the end of the film, after Chas (Fox) shoots Turner (Jagger) in the head, it’s Jagger that we see leaving the house with his old gangster cronies-presumably to be murdered by them. You meant to indicate that Chas had absorbed Turner’s persona?

Donald Cammell: In a sense, yes. I was thinking of Jorge Luis Borges and the Spanish bullfighter El Cordobes, who kisses the bull between the eyes before placing his sword therein. Jagger is very much that bullfighter. In terms of painting, if you look at the “Memo from Turner” number, Jagger’s character has already assumed the Harry Flowers persona (in terms of Chas’ perception). So this further absorption seems natural. The “Memo from Turner” sequence, by the way is probably the first rock video. You may not know it, but I’ve directed several rock videos in the last few years. In point of fact, I did a bit of editing on Gimme Shelter for the Maysles Brothers.

Excerpt from Edgardo Cozarinsky’s “Film on Borges”

The Argentine writer and filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky discusses Performance in his excellent essay, “Film on Borges,” collected in Borges In/And/On Film:

For years readers and critics recognized Borges by these labyrinths of time and space. Today they are more aware of his skeptical attitude toward the notion of the author, or, more plainly, of identity itself. The Borges of Performance and Les autres is still the same, but now his readers have also read R. D. Laing or Gilles Deleuze.

Performance responds to the same notion of identity as an assumed role—simultaneously a means of power and a trap—in order to portray the social comedy. Its main characters (a gangster taunted by his accomplices, a pop star fallen into an early decline) undergo violent and erotic turnabouts that are like initiation rites, until each recognizes the other as an alter ego, and they fuse. The film multiplies this game of facing mirrors: the shrill and fleeting scenes of the underworld are the negative image of the asphyxiating decor that protects the rock star, the secondary characters fulfill interchangeable functions, the word “performance” refracts in its multiple meanings (in the arts, in sex, in delinquency, in every exercise of power) a system of correspondences where each small part reproduces the whole design.

Written by Donald Cammell, photographed by Nicholas Roeg, and directed in indistinguishable collaboration by both, this ill-fated film was made in 1968, filed away by Seven Arts, cut and revamped by Warner, and finally released in 1970 with only marginal, equivocal success. Although it adapted no specific Borges text, Performance explicitly derives from all his work (and secondarily from Artaud, Norman O. Brown, and R. D. Laing). Borges appears repeatedly in the film: he crosses the screen twice in jacket photos on identifiable copies of his Personal Anthology; he makes himself heard in two quotations that the rock star interpolates in his dialogue (the first quotation from “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” the second from “The South”); and, at the end of the film, his picture emerges from the impact of a bullet fired point blank in the star’s face by the gangster—as if at the very instant of being obliterated Mick Jagger’s features could free that other, submerged face.

Because of its mixed refinement and brutality as well as its excesses, Performance is a cinematic phenomenon inaccessible to criteria, even though the film freely incorporates literary material. Perhaps is its greatest interest: not to reflect Borges in an analogous space. Except for Godard, whose work responded contemporary notions that a Burroughs or a Rauschenberg could handle, the other filmmakers who refer to Borges, with whatever degree of success, do it in intellectual, cultivated, and irremediably polished works. Only Performance inoculates the Borgesian element into an organism that functions differently. Even the esoteric quality of the film is not aristocratic; it belongs, instead, to the drug culture, to Hindu bric-a-brac, synthesizer music, bisexuality, and other popularized or tolerated cultural forms of latter-day capitalism. For the spectator with “good taste,” it can be irritating and even incomprehensible, as John Simon demonstrated in a rather lengthy attack: “…even that great writer, Jorge Luis Borges, is dragged into the cesspool. . . . It is all mindless intellectual pretension and pathologically reveled-in nastiness, and it means nothing” (“The Most Loathsome Film of All?”, The New York Times, 23 August 1970).

Excerpt from Joseph Lanza’s Fragile Geometry

The story’s complexity is congenial to Turner’s universe which is much like those described in the Borges stories to which the film periodically refers as tales within a tale. “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”is the name given to a world with inverted natural laws, whose objects have no clear definition and whose nouns exist as endless strings of adjectives. Preparing for his own imminent murder-suicide while Chas lurks in the basement like a waiting assassin, reads aloud from “The South,” which is about a convalescent who leaves his sanatorium for a train journey to an obscure province, engaging in a fatal knife fight pre-ordained the day he opens a volume of The Thousand and One Nights. But perhaps the most important story is “Death and the Compass,” which is never directly mentioned. Here, the police inspector tries to decipher an oracular series of homicides whose locations describe a geometric puzzle, the final piece completed only when the inspector himself enters the murderer’s carefully assembled lair. This is an understated allusion to Performance’s own geometric murder when Chas aims his gun precisely at the section of Turner’s head that corresponds to the patch of hair Chas mysteriously leaves on the chauffeur’s scalp. The connection becomes more obvious when Borges’s photograph flashes in a shattered looking glass as the camera takes us on a visceral tracking shot down Turner’s punctured skull.

Music

Originally intended for the closing credits, “Memo for Turner” became central to Performance. In 1996, Timothy White interviewed producer Russ Titelman, who worked with Jack Nitzsche on the Performance soundtrack. The following excerpts about the soundtrack are taken from “The Russ Teitelman Story” on SpectroPop.

White: In 1969, you found yourself playing guitar on ‘Memo From Turner’, for Jack Nitzsche’s soundtrack to the Mick Jagger film, Performance.

Titelman: Actually, the core of the studio band on that record was Randy Newman, Ry Cooder and myself, and it was recorded in Los Angeles at Western Studios. But Jagger wasn’t there during our sessions. The band Traffic had done a recording of ‘Memo From Turner’, but Jagger and Nitzsche didn’t like it. So we replaced their track, playing along to Jagger’s existing vocal and a click track. I played the Keith Richards-sounding “jing-a-jing” on rhythm guitar, and Ry Cooder did the slide guitar parts. They needed a song for the credits and Jack said he wanted to lyrically use all this voodoo and blues terminology for this story of this faded rock star, a burnt-out character who can’t get it up anymore. I saw the track part as Chuck Berry-like in feel but more raucous.

White: The Performance soundtrack marked your first recording for Warner Brothers Records, but what were the exact circumstances that led directly to your 25-year association with the label?

Titelman: Well, in the early ‘60s I used to go over to Reprise Records on Melrose and hang out with Steve Venet, who was the head of A&R there; Steve was the brother of Nick, who produced the Lettermen for Capitol. Anyhow, this was before Reprise, Sinatra’s label, was sold to Warners, and I used to see Mo Ostin there. Everything was completely informal then.

But, really, I was getting to know Lowell George at the time of Performance in 1969 that sorta led to Warner Brothers as a full-time thing. See, Lowell George, who worked uncredited on the Performance soundtrack, was a big fan of Ravi Shankar. Shankar had opened a school, the Kinara School of Music, and I met Lowell there because I was studying sitar there for a year. Although I couldn’t play sitar that well, Lowell could. Incidentally, George Harrison, who I would later produce, also came by and we were introduced. So Lowell and I got close and drove around all the time in this Morgan car he had, taking LSD and mescaline. Lowell was amazingly talented. He was a flute player in high school, and he knew how to play Japanese shakuhachi flute; anything he picked up he could figure out, and he of course was a truly great guitar player.

As we were studying sitar, Nitzsche was doing this Performance movie score with all sorts of different instrumentation, and I said, “Look, we’ll have tamboura and veena,” which I borrowed from the school. I played veena on one song, Buffy Sainte-Marie played these mouth-bow solos, and Lowell and all of us did this crazy stuff on the tracks. Jack also was smart enough to get Ry Cooder to come and play all this slide guitar. My sister Susan and Ry had met by then, but they weren’t married yet. Four years on, I would co-produce Ry’s ‘Paradise And Lunch’ album and co-write ‘Tattler’ with him, so Performance was the beginning of a lot of associations.

Meanwhile, Lowell was simultaneously playing with the Mothers Of Invention, and he was rehearsing his own band, Little Feat, and Lowell was going to sign with Lizard Records… The next thing I did after Little Feat was the ‘Randy Newman/Live’ album. I’d first met Randy at Metric Music, but we’d come to know each other well because of Performance.

Memo from Turner

Lyrics and Music by Mick Jagger and Kieth Richards

Didn’t I see you down in San Antone on a hot and dusty night?

We were eating eggs in Sammy’s when the black man there drew his knife

Aw, you drowned that Jew in Rampton as he washed his sleeveless shirt

You know, that Spanish-speaking gentlemen the one we all called Kurt

Come now, gentleman, I know there’s some mistake

How forgetful I’m becoming now you fixed your business straight

I remember you in Hemlock Road in nineteen fifty-six

You’re a faggy little leather boy with a smaller piece of stick

You’re a lashing, smashing hunk of man your sweat shines sweet and strong

Your organs working perfectly but there’s a part that’s not screwed on

Weren’t you at the Coke convention back on nineteen sixty-five?

You’re the misbred, gray executive I’ve seen heavily advertised

You’re the great, gray man whose daughter licks policemen’s buttons clean

You’re the man who squats behind the man who works the soft machine

Come now, gentleman your love is all I crave

You’ll still be in the circus when I’m laughing, laughing in my grave

When the old men do the fighting and the young men all look on

And the young girls eat their mothers meat from tubes of plasticon

Be wary of these my gentle friends of all the skins you breed

They have a tasty habit they eat the hands that bleed

So remember who you say you are and keep your noses clean

Boys will be boys and play with toys so be strong with your beast

Oh Rosie dear, don’tcha think it’s queer so stop me if you please

The baby is dead, my lady said, “You gentlemen, why, you all work for me”

Borges Postscript

Both Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell continued to be influenced by Borges.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

Nicolas Roeg’s third outing as a director, Don’t Look Now, is a cerebral horror film starring Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie as parents haunted by the death of their child. Memorably filmed in Venice and featuring another famously controversial sex scene, Don’t Look Now was recognized as “Borgesian” by several contemporary critics. Edgardo Cozarinsky discusses Don’t Look Now in his essay, “Film on Borges,” collected in Borges In/And/On Film:

Qualitatively, too, critics became increasingly alert to the presence of Borges in Roeg’s work, which had to sustain the long shadow of his influence. In that same Fall 1973 issue of Sight and Sound, [Jan] Dawson refers to “Borgesian form” and Tom Milne recognized a “Borgesian world” in Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. During the same year, the formidable Pauline Kael piled up seven references to Borges in her New Yorker piece on the Roeg film (24 Dec. 1973), saying that in “using Du Maurier as a base, Roeg comes closer to getting Borges on the screen than those who have tried it directly.”

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Nicolas Roeg’s fourth film, The Man Who Fell to Earth, stars David Bowie as a homesick alien stranded on earth. And yes, there’s a controversial sex scene, but less for its authenticity than its…well, see the movie. Naturally, Cozarinsky discusses The Man Who Fell to Earth in his essay, “Film on Borges,” collected in Borges In/And/On Film:

By 1976 it was not only Roeg, predictably enough, with The Man Who Fell to Earth but also Francesco Rosi with Cadaveri eccelenti who provoked references to Borges—closer to unanimity and insignificance in each instance. An exception to be singled out is Ronald Christ’s brilliant essay on The Man Who Fell to Earth (published in the St. Louis Literary Supplement I:1, November 1976), where Roeg’s search for a “new film grammar” is associated with the “assault on our metaphysic, which man of us prefer to call psychology.” Roeg’s film is read by Christ as having a “metaphysical base” in the literature of, among others, Borges, “who have launched an unremitting attack on the notion of the individual self.”

Demon Seed (1977)

After Performance, Donald Cammell’s most significant film was Demon Seed. Based on a story by Dean Koontz, Demon Deed features a rampant artificial intelligence named Proteus IV. Placed in charge of a gleaming modern home, Proteus attempts to create life by imprisoning, raping, and impregnating his programmer’s wife, gamely played by Julie Christie. Early in the film, Proteus asks a question drawn directly from Borges’ “The Wall and the Books” in Other Inquisitions.

From the screenplay of Demon Seed:

Alex, I’d like to hear it speak.

It speaks, doesn’t it?

“Shihuangdi…

…the first emperor of China…

…built a wall 3000 kilometers long…

…to protect civilization

from the barbarians.

The Great Wall of China.

Then decided,

‘History will begin with me.

I will destroy the past.’

And he ordered all the books

in his empire to be burnt.”

Burnt.

Proteus, this is Dr. Harris.

—Can you see me?

—Yes…

…I can see you, Dr. Harris.

Your favorite emperor.

What do you think of this

enigmatic man?

Nothing.

Nothing.

—Have you no answer?

—Nothing…

… is the answer.

The emperor’s business enterprises…

… his wall building

and book burning…

… are opposite terms in an equation.

The net result is exactly…

… zero.

Gentlemen, the philosophy

is pure Zen…

… and the method is pure science.

Did you intend me to be so pure, or…?

Thank you, Proteus.

And this includes our children…

…as machines to be systemized

in order to ensure product.

Bibliography

Books

Cozarinsky, Edgardo. Borges In/And/On Film. Lumen Books, 1988.

Glennie, Jay. Performance: The Making of a Classic. Coattail Publications, 2018.

Lanza, Joseph. Fragile Geometry: The Films, Philosophy and Misadventures of Nicolas Roeg. PAJ Publications, 1989.

Levy, Shawn. Ready, Steady, Go!: The Smashing Rise and Giddy Fall of Swinging London. Broadway Books, 2002.

Perry, Keith and Jack Hunter. Bullet In the Brain (Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg’s “Performance”). Creation, 2010.

Robinson, Jeremy Mark. Performance Pocket Movie Guide. Crescent Moon Publishing, 2015.

Roeg, Nicolas. The World Is Ever Changing. Faber and Faber, 2011.

Articles and Interviews

Interview with Donald Cammell

David Del Valle interviews Donald Cammell for Video Watchdog magazine.

The Most Loathsome Film of All?

John Simon, The New York Times, 23 August 1970. One of the most priggish and deranged movie reviews to ever issue from the Gray Lady, with some blatant homophobia to boot!

Cinema Sex Magick: The Films of Donald Cammell

Chris Chang, Film Comment, July-August 1996. An excellent piece on the films of Donald Cammell, published by “Films at Lincoln Center.”

The Man That Time Forgot

Paul Beard and Lee Hill, Neon, August 1997. An article on Donald Cammell, online at PhinnWeb. Contains some information about the filming of Performance.

Donald Cammell’s Performance at Powis Square

7 January 2009, Another Nickel in the Machine. This blog devoted to twentieth-century London features a fascinating article about the location and shooting of Performance.

Smoke and Mirrors

Richard Flint, Photography Blog, 16 March 2014. A compassionate profile about the mysterious and unfortunate Michèle Breton.

Mirrors, Donald Cammell and Jorge Luis Borges

Adam Scovell, Celluloid Wickerman, 31 August 2015. A look at Donald Cammell’s suicide, his fascination with mirrors, and the Borgesian influence on his work.

Interview with Producer Sandy Lieberson

The Guardian, 16 November 2018. Tim Jonze interviews Sanford Lieberson, the film’s producer, and Jay Glennie, author of Performance: The Making of a Classic.

‘Performance’: Inside the Rock ‘n’ Roll Movie Too Shocking for the ‘60s

Christian Blauvelt, IndieWire, 13 February 2019. A 50th anniversary appraisal of Performance.

Additional Information

Additional Information

Performance Script

Donald Cammell’s stream-of-consciousness script is online at Scripts.com.

IMDB’s Performance Page

The Internet Movie Database’s page on Performance.

Wikipedia Performance Page

Wikipedia hosts an informative page on Performance.

PhinnWeb Performance Page

An excellent page devoted to the film, with images, articles, reviews, and more.

“Memo from Turner” Video

The original video from the film used to be on YouTube, but the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel blocked it on copyright grounds. (Thanks, France.) Anyway, this version is something of a mash-up, but if you can ignore the asynchronous lip movements, it gets the point across.

Authors: Allen B. Ruch & John Coulthart

Last Modified: 28 August 2024

Borges Film Page: Borges & Film

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Look, I need a…

I need a bohemian atmosphere.

I’m an artist, Mr. Turner.

Like yourself.

—You juggle?

—Why not?

Why, why not? Why not a jongleur?

It’s the third oldest profession.

You’re a performer of natural magic.

I… I perform.

I bet you do.

I can tell by your vibrations…

…you’re the anti-gravity man!

Amateur night at the Apollo.

Cheops in his bloody pyramid.

He dug a juggler or two, didn’t he?

Remember?

And the tetrarchs of Sodom…

…and Orbis Tertius.

Am I right? Am I right, babe?

More or less.

Personally, I just, you know…

…perform.—Donald Cammell, Screenplay to “Performance”