Borges – Memoirs

- At August 05, 2023

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

To think of him is to think of an intimate friend, one we have never seen but whose voice we know and every day miss.

—Jorge Luis Borges on Oscar Wilde, Atlas, 1984

Borges Biographies & Memoirs: Memoirs

This page profiles English-language memoirs about Borges. They are listed in chronological order of publication. Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

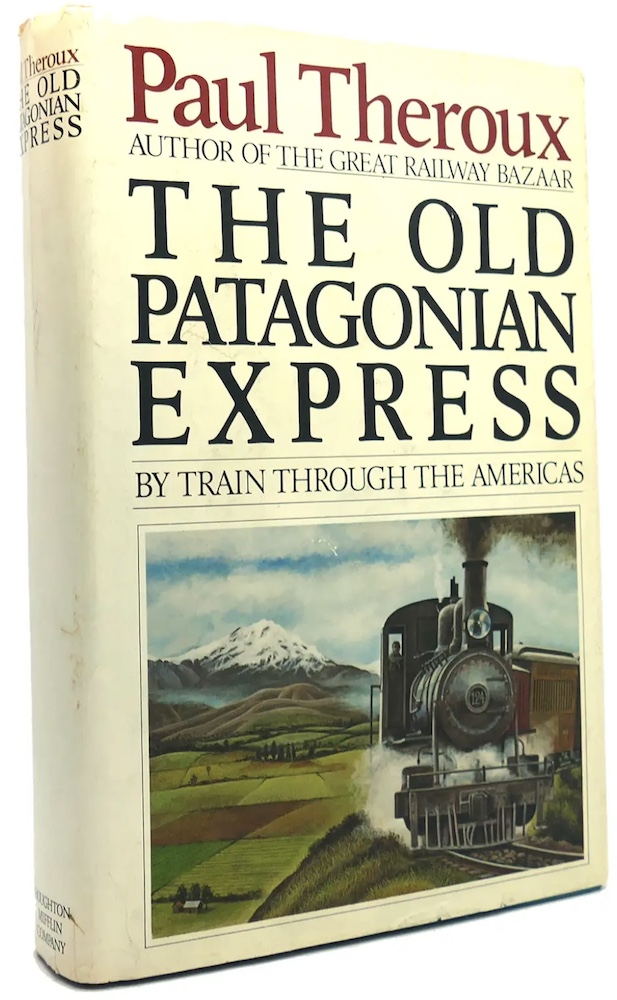

The Old Patagonian Express: By Train Through the Americas

The Old Patagonian Express: By Train Through the Americas

By Paul Theroux

Houghton Mifflin, 1979

Online at: Internet Archive

Paul Theroux’s famous 1979 travelogue contains an anecdote of meeting Borges in Argentina.

Publisher’s Description: In The Old Patagonian Express, Theroux rides the more or less continuous track from his home in Boston to the Great Plain of Patagonia in southern Argentina. His writer’s eye misses no detail, and he serves up delights such as the brawling soccer fans of El Salvador, a bogus priest in Cali, and a desperate American woman searching for her lover in Veracruz. To this he adds an extraordinary account of his meeting with author Jorge Luis Borges in Argentina.

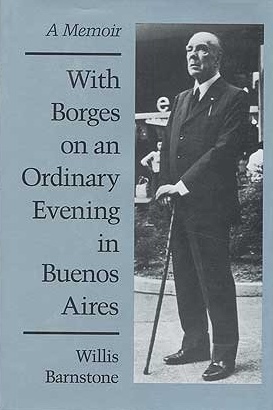

With Borges on an Ordinary Evening in Buenos Aires: A Memoir

With Borges on an Ordinary Evening in Buenos Aires: A Memoir

By Willis Barnstone

University of Illinois Press, 1993

Borges’ longtime friend and translator Willis Barnstone created this memoir from his years working with Borges. Until the Garden gets its own review online, here are a pair of opposing viewpoints, with the latter a more accurate assessment:

From Publishers Weekly :

The author first met Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) at a New York City poetry reading in 1968; their friendship deepened through the following years in encounters held in Buenos Aires and Cambridge, Mass. In this intimate, invaluable portrait, Barnstone, a professor of comparative literature at Indiana University, presents the poet-storyteller as a figure of paradox and contradictions. Nearly blind in his last decades, Borges longed for his life to end; he was obsessed with the instant after death that, he hoped, would reveal the mysteries of the universe. We see Borges, in place of the popular image of the cerebral metaphysician, as an itinerant sage, a tender lover who married his muse María Kodama on his deathbed, a troubled sleeper whose nightmares were filled with mazes. Barnstone’s fluent translations of Borges’s verses enliven these reminiscences and conversations.

From Library Journal:

This whimsical account intersperses random recollections of desultory musings on such topics as death, suicide, and, especially, literature, with both pithy sayings (“We are always inventing the past’’) and snatches of poetry from Argentine master Jorge Luis Borges. As outtakes from Barnstone’s journal, transcribed during the 1970s and 1980s, about his worldwide travels and encounters with Borges, the reminiscences smack of déjà vu, recalling in particular his more illuminating Borges at Eighty, from which he has cloned an entire interview. The final product is a work that is too much Barnstone and not enough Borges. Not an essential purchase.

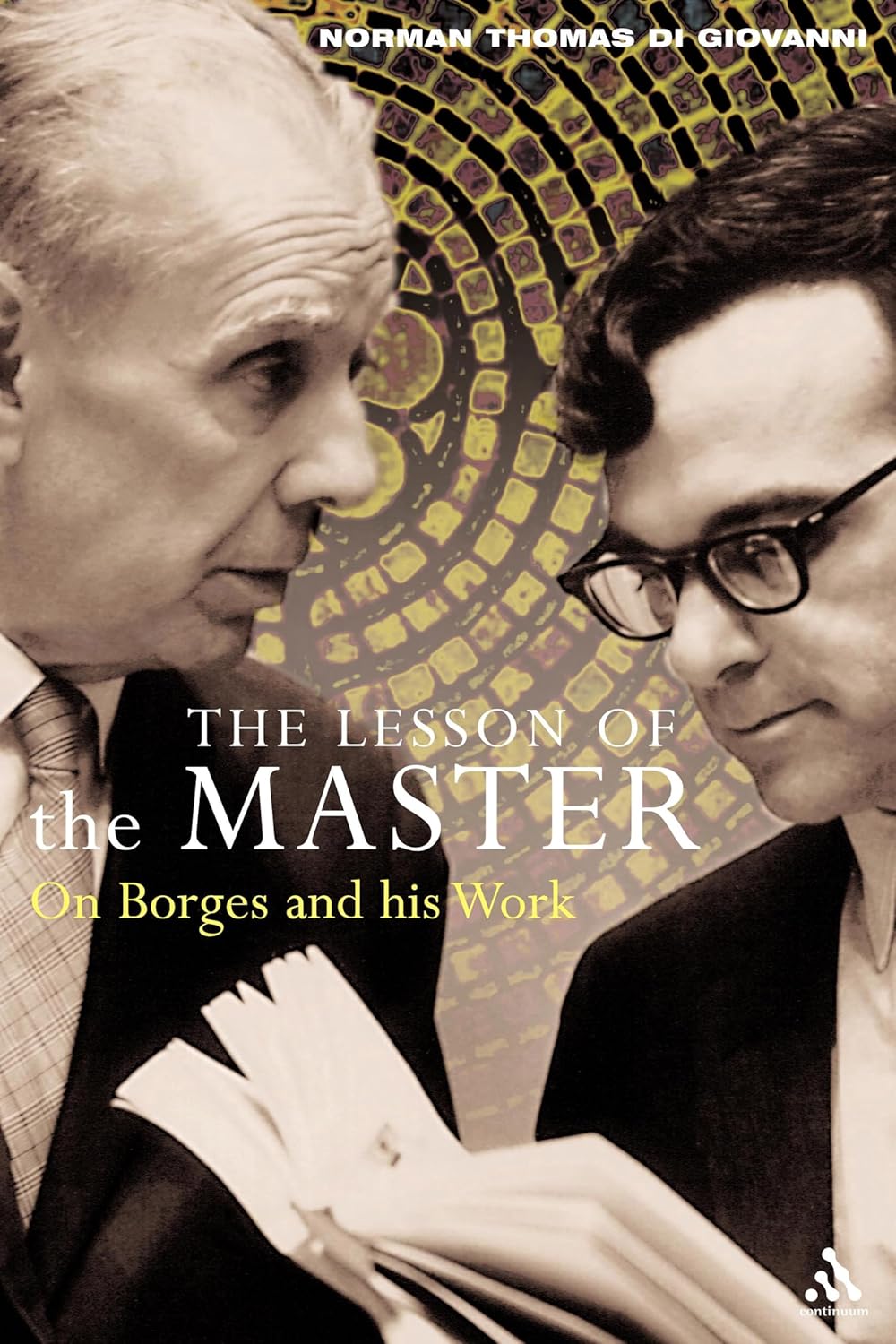

The Lesson of the Master: On Borges and His Work

The Lesson of the Master: On Borges and His Work

By Norman Thomas di Giovanni

Continuum, 2003

A collection of memoirs, notes, essays, and previously unpublished translations by Norman Thomas di Giovanni (1933–2017), Borges’ lifelong friend, translator, and sometimes collaborator. Having run somewhat afoul of Borges’ widow María Kodama, di Giovanni watched his translations replaced by Viking/Penguin and eventually fall out of favor. Cut off from an important stream of financial support, he began writing books about Borges and his circle, such as his 2014 “tell-all” Georgie & Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife. This earlier memoir is considerably more fond, but still animated by di Giovanni’s irreverence and flinty humor.

Publisher’s Description: The Lesson of the Master—a memoir and essays—is an indispensable work for Borges readers of all kinds. Di Giovanni is the only translator to have had Borges to hand on a daily basis to contradict or authorize his work. He is not burdened with an over-reverence for his subject but is on the contrary playful, robust and witty. These translations of the stories that Borges generated himself, in collaboration with Norman Thomas di Giovanni, have been sidelined in the past as they were not included in the volumes of Borges’ work previously published in English. The Lesson of the Master is an essential illumination of one of the great masters of twentieth-century literature.

Additional Information

The Wayback Machine still maintains pages from Norman Thomas di Giovanni’s Web site, which is worth reading for his uncompromising views of the Borges estate. It also reprints some of the material from The Lessons of the Master.

Con Borges

With Borges

Con Borges By Alberto Manguel Grupo Editorial Norma, 2003 |

With Borges By Alberto Manguel Telegram Books, 2006 Online at: Internet Archive |

In 1964, Alberto Manguel was a sixteen year old clerk at Pigmalion, a Buenos Aires bookstore frequented by Borges. One day Borges asked Manguel if he’s like to become one of his “readers,” spending evenings at Borges’ apartment and reading to the blind writer from his collection of books. Manguel accepted, and thus began a friendship that lasted until Borges’ death in 1986.

Manguel went on to become a well-regarded writer himself, his books praising the virtues of bibliophilia and expressing an almost mystical appreciation for libraries. In 2003 Manguel published Con Borges, a memoir of his teenage years reading for Borges. Translated into French, it won the 2003 Prix du livre en Poitou-Charente, and was quickly translated into English by Manguel himself.

With Borges it is not a lengthy book; double-spaced, it occupies 77 pages, and can be read in under two hours. Manguel’s narrative alternates between italicized “direct impressions” of Borges seen through the eyes of a young reader, and longer, more mature reflections offered by an adult Manguel many years after Borges’ passing:

‘Can you write this down?’ He means the words he has just composed and which he has learned by hear. He dictates them one by one, intoning the cadences he loves and speaking out the punctuation marks…

For Borges, the core reality lay in books; reading books, writing books, talking about books. In a visceral way, we was conscious of continuing a dialogue begun thousands of years before and which he believed would never end. Books restored the past. ‘In time,’ he said to me, ‘every poem becomes an elegy.’ he had no patience with faddish literary theories and blamed French literature in particular for concentrating not on books but on schools and côteries.

This dual narrative is surprisingly effective at conveying the sensation of genuine memory with all its dreamy timelessness, dislocated chronologies, and sudden flashes of precision.

For those already acquainted with Borges through his many biographies and interviews, With Borges treads familiar ground, and Manguel offers little new information. We hear of Borges’ spartan apartment, his close relationship with his mother, and his encyclopedic memory for recitation. However, Manguel’s fondness for Borges infuses every sentence with unaffected warmth, and here and there a moment of quiet revelation slips through—Borges’ vest-pocket handkerchiefs, quietly perfumed by his maid; his periodic discovery and loss of Mozart; the blind writer using his library as a bank vault, squirreling away bills in the pages of his books, only to retrieve them months later with (sometimes) uncanny precision.

Even more interesting are Manguel’s criticisms of Borges, offered with the reluctant air of a disappointed nephew reproving a beloved uncle. While these flaws are not enough to irredeemably tarnish his mentor, Manguel offers no excuses for them either, and rebukes Borges’ casual racism, his disingenuous lapses of memory, and his occasional moments of cruelty. This latter quality is illustrated by one of the most interesting anecdotes in the book. Manguel’s tale of Borges quietly crushing a lesser writer attempting a misguided homage is brutal but undeniably funny:

But he could also be pointedly cruel. Once, as we were sitting in the living room, a writer whose name I don’t want to remember came to read to Borges a story he had written in his honor. Because it dealt with knifers and hoodlums he thought Borges would enjoy it. Borges prepared himself to listen; the hands on the cane, the slightly parted lips, the eyes staring upwards suggested, to someone who did not know him, a sort of polite meekness. The story was set in a tavern filled with low-life characters. The neighborhood police inspector, known for his bravery, comes in unarmed and merely through the authority of his voice forces the men to give up their weapons. Then the writer, with enthusiasm, began listing them: ‘a dagger, two revolvers, one leather cosh…’ Borges picked up in his deadly monotone voice: ‘Three rifles, one bazooka, a small Russian cannon, five scimitars, two machetes, a mean pop-gun…’ The writer managed a small laugh. But Borges continued relentlessly: ‘Three sling-shots, one brickbat, an arbalest, five poleaxes, one battering ram…’ The writer stood up and wished us goodnight. We never saw him again.

It’s the arbalest that gets me, every time! It’s also refreshing to hear confirmation about Borges’ presumed dislike of Pablo Neruda and Gabriel García Márquez, two writers Manguel includes in his insightful account of Borges’ literary blind spots:

One could construct a perfectly acceptable history of literature consisting only of the authors Borges rejected: Austen, Goethe, Rabelais, Flaubert…, Proust, Zola, Balzac, Galdós, Lovecraft, Edith Wharton, Neruda, Alejo Carpentier, Thomas Mann, García Márquez, Amado, Tolstoi, Lope de Vega, Lorca, Pirandello…

Another highlight of the book are pages Manguel devotes to Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo, the couple who entertained Borges nightly at their apartment. Particularly fascinating is Manguel’s portrait of the mysterious Silvina Ocampo; whose sardonic stories and “black humor” were always too “cruel” for Borges’ taste:

During the conversation, in which she did most of the talking in a sort of incantatory rhythm that haunted one for many hours afterwards, she would keep her face in the shade and her eyes behind thick dark glasses because she felt that she had ugly features, and would try to draw one’s attention to her beautiful legs, which she crossed and uncrossed incessantly.

She loved dogs. When her favorite dog died, Borges found her in tears and tried to console her by telling her that there was a Platonic dog beyond all dogs, and that every dog was The Dog. Silvina was furious, and in no uncertain terms told him to go stuff it.

These paired anecdotes nicely demonstrate the strengths of Manguel’s prose. His writing is clear and direct, yet rings with lyricism, each sentence perfectly polished without the appearance of labor. He presents his subjects with a novelist’s eye for detail, sensitive to unexpected sympathies and sounding grace notes of subtle humor. While readers may wish Manguel’s memoirs were longer, With Borges is a very pleasant way to spend an afternoon!

Medio siglo con Borges

Medio siglo con Borges

By Mario Vargas Llosa

Alfaguara, 2020

A book about Borges by the Nobel Prize-winning Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa. According to the author’s introduction:

This collection of articles, conference notes, and reviews bears witness to more than half a century of reading by an author who has been for me, since I read his first stories and essays in Lima in the 1950s, an inexhaustible source of intellectual pleasure. I have reread Borges many times and, unlike what happens to me with other writers who marked my adolescence, he never disappointed me. On the contrary, each new reading renews my enthusiasm and happiness, revealing new secrets and subtleties of that very Borgesian world; unusual in its themes and so diaphanous and elegant in its expression.

The book has yet to be translated into English, but given the caliber of the author, an English translation is surely inevitable!

Borges and Me: An Encounter

Borges and Me: An Encounter

By Jay Parini

Cannongate Books, 2021

Publisher’s Description: In this evocative work of what the author in his Afterword calls “autofiction” or “a kind of “novelised memoir,” Jay Parini takes us back fifty years, when he fled the United States for Scotland. He was in frantic flight from the Vietnam War and desperately in search of his adult life. There, through unlikely circumstances, he met famed Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges. Borges was in his seventies, blind and frail. Parini was asked to look after him while his translator was unexpectedly called away. When Borges heard that Parini owned a 1957 Morris Minor, he declared a long-held wish to visit the Scottish Highlands, where he hoped to meet a man in Inverness who was interested in Anglo-Saxon riddles. As they travelled, the charmingly garrulous Borges took Parini on a grand tour of western literature and ideas while promising to teach him about love and poetry. As Borges’s world of labyrinths, mirrors and doubles shimmered into being, their escapades took a surreal turn.

Borges Biography & Memoir

Main Page — Return to the Borges Biography & Memoir main page and index.

Biographical Sketch — The Garden’s biographical sketch on Borges.

Borges Biographies — English-language biographies written about Borges.

Authors: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 30 August 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com