Breech Rifles

- At December 23, 2016

- By Great Quail

- In Armory, Deadlands

1

1

Rifles Part II. Breech-Loading and Metallic Cartridges

Breechloaders

Since the dawn of black powder, gunmakers have explored ways of loading firearms from the opposite—and significantly closer!—end of the barrel. Hinged breeches, loading gates, and detachable chambers date back to the matchlock period, and even Henry VIII owned a few guns loaded in a manner not unlike a “Trapdoor” Springfield. However, such experimental firearms were prohibitively expensive, and never achieved anything more than novelty status among the wealthy. It was not until the nineteenth century that improvements in engineering techniques and ammunition types made breech-loading firearms a viable alternative to muzzle-loaders.

A New Age

In the early1860s, breech-loading firearms finally began to supplant muzzle-loaders. While the difference may appear minor—the rifle is loaded from the rear of the barrel, rather than the muzzle—the implications are enormous. Faster to reload, requiring less auxiliary equipment, and easier to clean, breech-loading rifles could achieve significantly higher rates of fire—up to ten rounds a minute in the hands of an experience shooter! They can also be reloaded from a prone or sitting position. The trade-off comes with an increase in complexity, as breech-loaders require some form of mechanical “action” to open the breech, expose the chamber, and reseal the breech. Most breech-loaders are classified by the system used to accomplish this process, which usually involves the movements of the “breechblock,” the metal component which physically seals the breech-end of the barrel and permits the rifle to be fired safely.

Merrill Carbine with the breechblock opened, 1858–1861

Merrill Carbine with the breechblock opened, 1858–1861

Breech Blow-By

Early breech-loaded rifles used paper or linen cartridges, in which a lead bullet was backed by a measure of gunpowder propellant. When ignited by the percussion cap primer, the gunpowder exploded directly inside the chamber, with some of its explosive force inevitably escaping from the breech in a blast of hot gas. This leakage decreased the velocity of the bullet, reduced the accuracy of the rifle, and fouled the inner workings of the action. It can also scorch or irritate the shooter. For this reason, early breech-loaders struggled to find methods of “obturation,” or forming an effective gas seal to contain the explosive energy of the propellant.

The mid-1850s to early-1860s were a period of widespread experimentation in firearms, with dozens of patents being awarded to a variety of new breech-loading designs. The majority of these designs operated the breechblock by using the trigger-guard as a lever. When the shooter activates the lever, the breechblock either tilts up or drops down, both methods granting access to the chamber. A paper cartridge is inserted into the chamber and the breech is closed by returning the lever. A few models used mechanical trapdoors to grant access to the chamber from the top of the frame. All of these early designs had to contend with the problem of breech blow-by, which reduced the accuracy and range of the firearm. Although some early breech-loaders were produced as long rifles, the shorter range of carbines was less impacted by gas leakage, so many of these early breechloaders were offered as carbines. More than a few also used the Maynard tape priming system. The most interesting or successful of these carbines are individually profiled in the Armory below, but there are dozens more that have vanished into obscurity; produced in limited numbers and known only to collectors. Marshals and players wishing to resurrect some of these nineteenth-century rarities are free to research historical models, with the following statistics offering a generic template: Caliber .50 to .54, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10.

A few examples of possible interest include the Jenks “Mule Ear” Carbine of 1843–1846; the Greene Carbine of 1855–1856; the Gibbs Carbine of 1856–1863, which ended production after the Phoenix Armory was destroyed during the New York Draft Riots; the exceptionally rare Symmes Carbine of 1857; the Perry Carbine of 1857; the Maynard Carbine of 1858–1860; the Merrill Carbine of 1858–1861; the Lindner Carbine of 1859–1863; and the Brand Carbine of 1863–1865. As usual, details may be found by consulting the trusty Flayderman’s Guide or conducting a simple Internet search.

Metal Cartridges

During the mid-to-late 1860s, percussion caps and combustible paper cartridges were rendered increasingly obsolete by the introduction of metal cartridges, in which the bullet, propellant, and primer are encased within the same unit. The bullet is discharged when a firing pin strikes the base of the cartridge, setting off the primer and exploding the gunpowder contained within the metal shell. Because metal expands when heating, the hot casing forms a gas seal, directing the explosive energy forward. Metal cartridges are designated as “rimfire” or “centerfire,” depending on where the firing pin strikes the case. Copper was generally used until the mid-1870s, after which most armorers switched to brass, which was more expensive but more effective. Of course, the spent casing must be extracted, an additional mechanical process that adds further complexity and invites potential malfunction. Spent centerfire casings may be retained for “reloading,” but rimfire casings are ruined by the firing process.

|

|

| Rimfire revolver & centerfire rifle | Spencer Cartridges: .56-52, .56-56, .56-50 |

Metal cartridges are often specified by a sequence of numbers, such as the .45-70-405 “Government” round. The first value gives the caliber of the bullet in inches, the second the grain weight of powder, and the third the grain weight of the bullet. Cartridges developed for the Spencer repeater are given two hyphenated numbers, such as the .56-52 Spencer or the .56-50 Springfield. The first value is the width of the cartridge base in inches, followed by width of the cartridge mouth. The degree of taper may be seen in the difference between these values, with the actual bullet caliber being closer to the second number. For instance, the .56-52 and the .56-50 were both fitted for a .512 caliber bullet; the latter version just has a greater “crimp.”

|

|

The efficiency of metal cartridges paved the way for smaller-caliber rounds. Because of the high muzzle velocity of smaller bullets, smaller-caliber rifles are more accurate and have a greater effective range than large-caliber muzzle-loaders. The trade-off is a reduction in damage and stopping power.

Schuetzen & Creedmoor Rifles

Two rifle variants detailed in the Armory are the “Schuetzen” and the “Creedmoor.” Both are examples of competition rifles, especially designed for nineteenth-century shooting competitions.

Schuetzen Rifles

Derived from the German word Schütze, or “rifleman,” a Schuetzen event is a long-range competition in which marksmen compete using targets placed at 600 yard ranges. Competitors often use custom rifles with heavy frames, dual set triggers, and precision barrels. These “Schuetzen rifles” are prized for their beauty, and often feature elaborate engravings and curling “Swiss-style” buttplates.

This Schuetzen rifle was designed by Munich gunsmith Adam Schurk in 1925.

Creedmoor Rifles

In 1872, the New York State legislature and the newly-established National Rifle Association purchased seventy acres of farmland in Queens from one “Mr. Creed.” Their goal was to establish a competitive international shooting range. Jokingly named “Creedmoor” as a nod to British competitions, the range opened up a year later, with the Central Railroad of Long Island establishing a nearby train station for easy access.

Remington Rolling Block “Creedmoor” Rifle

Creedmoor proved to be a resounding success, attracting completive shooters from all over the world and establishing the Leech Cup and Wimbledon Cup for long-range shooting events. “Creedmoor” rifles are engineered for accuracy, but must conform to the NRA’s Creedmoor regulations—they may only have one trigger and must weigh under ten pounds. The event also gave its name to a long-range firing position. A shooter in the “Creedmoor position” reclines on his back and supports the rifle with his body.

The Armory: Breech-Loaders

Break-Action Flintlock

1600–1840s, breech-loading flintlock. Caliber .50 to .69, Range 10/80/160, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3 to 1/2, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Exceptionally rare. Note: The Rate of Fire depends on the cartridge type; 1/2 if the pan is included, 1/3 for powder and shot only.

The ancestor of the double-barrel shotgun, a “break-action” flintlock features a hinge that allows the user to swing the barrel downward to expose the bore. This hinge is activated by some form of locking latch, usually a lever or toggle integrated into the trigger guard. The shooter inserts a reusable steel cartridge into the breech and closes the action. Dating from the matchlock period and allegedly invented by Leonardo Da Vinci, these cartridges are preloaded with gunpowder and shot, and are carried in a case along with several ready replacements. Often, a break-action flintlock is equipped with an automatic priming system. Some gunmakers prefer a different solution, and integrate an individual priming pan and frizzen into each cartridge. Essentially serving as exchangeable chambers, these cartridges lock neatly into place under the hammer.

Break-action flintlock by Henry Delaney Break-action flintlock by Henry Delaney |

Reusable cartridge with pan and frizzen. Reusable cartridge with pan and frizzen. |

Expensive to produce, break-action flintlocks were never intended for the common shooter, and were primarily manufactured in England and Germany. A few gunmakers associated with this style include Nicholas Paris, Robert Rowland, James Freeman, J.A. Wadt, and George Grebe. It was also popular among certain Huguenot gunsmiths who fled France after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, such as Andrew Rhinehold Dolep and Henry Delaney.

Close-up of the Grebe Break-Action Rifle seen above, circa 1690

Ferguson Ordinance Rifle

1776–1778, UK. Rotating breechplug, flintlock. Caliber .65, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Very rare.

Invented by Scottish major Patrick Ferguson in 1770, this early breech-loaded rifle was an improvement to a French design by Isaac de la Chaumette. To load the Ferguson, the shooter unlatches the trigger guard, which is free to rotate like a crank. A single clockwise rotation turns the eleven threads of the “breechplug,” a screw-like breechblock that spirals down from the bottom of the frame. This action exposes the chamber through a hole at the top of the frame. A .65 caliber ball is inserted into the cavity, and the barrel is tipped downward to seat the ball against the rifling. After the powder is loaded, the trigger-guard is cranked counter-clockwise to return the breechplug and seal the breech. As the breechplug rotates upward, spare gunpowder is pushed to the top of the frame and brushed into the pan for use as primer. The frizzen is closed, the hammer is cocked, and the rifle is ready to fire.

|

|

Capable of firing six rounds per minute, the Ferguson was quite effective in the hands of specially-trained riflemen. Unfortunately, the screw-mechanism broke easily, and the Ferguson was expensive to manufacture. With only two hundred placed into production by the London gunsmith Durs Egg, Ferguson rifles saw limited use in the American Revolution, where Major Ferguson and his “Experimental Rifle Corp” carried them in the Battle of Brandywine Creek. Unfortunately, Ferguson was wounded during the battle. During his convalescence, the British government disbanded his unit and placed the experimental rifles into storage in New York.

With his right arm permanently maimed, the injured Scot returned to the War with orders to intimidate patriots and recruit loyalists. He quickly developed a reputation for exceptional cruelty, reputedly ordering his troops to bayonet sleeping rebels during the Little Egg Harbor Massacre. In 1780, Major Ferguson was killed during the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina. Riddled with musket balls, his body was stripped naked by the patriots, who took turns urinating on his corpse before burying him with his mistress, also slain in the battle. Ferguson’s namesake rifle was deemed a failure by Great Britain; and while a few showed up in Southern hands during the Civil War, it remains an intriguing reminder of a historical path not taken.

U.S. Model 1819 Hall Breech-Loading Flintlock Rifle

1819–1840, USA, pivoting-block, flintlock. Caliber .52, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Rare.

In 1811, Maine inventor John Hancock Hall received a patent for a breech-loading flintlock rifle. Partnering with D.C. architect William Thornton, John Hall began producing his rifle in small numbers, until the U.S. Ordnance Bureau requested an order of two hundred. After giving it some thought, Hall suggested that he could produce an even larger order if he had access to an assembly process using precision machinery and interchangeable parts. He wrote, “Only one point now remains to bring the rifles to the utmost perfection, which I shall attempt if the Government contracts with me for the guns to any considerable amount, viz. to make every similar part of every gun so much alike that if a thousand guns were taken apart & the limbs thrown promiscuously together in one heap they may be taken promiscuously from the heap and will all come right … although in the first instance it will probably prove expensive, yet ultimately it will prove most economical & be attended with great advantages.”

Harpers Ferry & Hall’s Rifle Works

Given the recent success of Eli Whitney employing similar techniques to Springfield patterns, the Army agreed to Hall’s proposal, but dispatched him to Harpers Ferry, where more traditional methods of manual assembly were still the norm. Hall occupied an old sawmill adjacent to the armory on Virginius Island, the series of lots carved from the Shenandoah by various canals and millraces. Hall spent the next few years developing a quasi-independent workshop guided by the “uniformity principle.” Eventually known as “Hall’s Rifle Works” on “Hall’s Island,” the workshop used running water to power a wide variety of machine tools, and soon rivaled—some would say, surpassed—“Whitneyville” in New Haven. By 1824, Hall had produced a thousand virtually identical Model 1819 rifles, making it the first mass-produced breech-loaded rifle in the world. In 1830, Connecticut inventor and fellow “interchangeable parts” pioneer Simeon North contracted to make 5,700 Model 1819 rifles in Middletown, establishing a productive relationship that lasted the entire life of Hall’s patent, and impressing John Hall with his own technological ingenuity.

The Model 1819 Rifle

In many ways, the Model 1819 is a transitional firearm, bridging the gap between muzzle-loaders and breech-loaders. In fact, Hall anticipated that some shooters may load the Model 1819 through the muzzle, so the rifling does not begin until an inch-and-a-half past the muzzle, a design that facilitates ramming a ball home. For the majority of shooters content to leave the ramrod in place, the breech is opened by pulling a hook-shaped catch protruding from the bottom of the frame. This releases the breechblock, which pivots upwards to expose the chamber. Essentially the rear segment of the barrel, its large size necessitates a wide breech, giving the Hall frame its distinctive diamond-shaped bulge. The cartridge is loaded from the front—another transitional aspect—and the breechblock is locked back down. The pan is primed, the hammer fully cocked, and the flintlock is ready to fire. The product of early machine tooling, the Model 1819 relies on tightly-engineered components to seal the breech; an imperfect system that results in significant breech blow-by and a reduced accuracy and range.

Hall rifle with breechblock open and ready to load

Hall Carbine, Model 1833 to Model 1842

1833–1844, USA, pivoting-block. Caliber .52, Range 6/60/120, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon to very rare. Note: These general statistics may be used for any Hall carbine, with damage adjusted for variations in caliber.

1836 Hall Carbine with sliding ramrod bayonet

The Hall patent proved quite dependable over the next few decades, and was used for a number of smoothbore percussion carbines made at Harpers Ferry or contracted to Simeon North. Chambered for .52 or .58 caliber rounds, the U.S. Model 1833 Hall-North Carbine was the first percussion firearm adopted by U.S. forces, and features a sliding “ramrod” bayonet. The .64 caliber U.S. Model 1836 Hall Carbine was produced in smaller numbers, and saw use against the Seminoles by the 2nd Dragoons. The Model 1840 Hall-North Carbine changed the operating lever, with the rare Type I featuring an “elbow” lever and the more common Type II equipped with a less-obtrusive “fishtail” lever.

Model 1840 Type I Hall Carbine with “elbow” lever

Model 1840 Type II Hall Carbine with “fishtail” lever

The Model 1841 Hall Rifle retained the fishtail lever, as did the Model 1842 Hall Carbine, which added brass furnishings. John Hall continued to work at Harpers Ferry until 1840, producing over 30,000 firearms and occasionally coming into conflict with the more traditional armorers who resented this Yankee upstart and his newfangled methods. As his health declined in the late 1830s, conditions at Hall’s Rifle Works began to deteriorate, and frequent flooding inflicted excessive wear-and-tear on his precision machines. Indeed, these flooding conditions resulted in Hall developing a distinctive browning lacquer used on Harpers Ferry firearms to protect them against corrosion; a recipe that he carried to his grave in 1841.

U.S. Model 1843 Hall-North Breech-Loading Percussion Carbine

1844–1853, USA, pivoting-block. Caliber .52, Range 8/80/160, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon. Note: The re-bored .58 carbine is DAM 1d10+1d12.

After Hall’s death, the Model 1841 Carbine was the last Hall patent produced at Harpers Ferry; but Simeon North had one final trick up his sleeve. The last firearm to use Hall’s patented breech, the Model 1843 Hall-North Carbine replaced the Model 1840’s fishtail lever with a thumb-operated lever located on the right side of the breech.

With over 10,000 placed into production, the Model 1843 saw use during the Mexican-American War and the early days of the Civil War. In 1861, General Ripley of the Ordinance Bureau arranged to have five thousand of these aging carbines purchased from an arsenal in New York. Through a series of deals supported by loans from J.P. Morgan, the carbines were bought for $3.50 apiece, re-bored to .58 caliber at the cost of 75¢ each, and sold to General John C. Frémont at a cost of $22.00 each, with Morgan holding up delivery until the government paid the outrageously inflated price. Known as the “Hall Carbine Affair,” this war-profiteering scheme enraged the nation, and was one of the reasons President Lincoln removed the scandal-ridden Frémont from his position as Commander of the Department of the West.

Sharps Model 1849 Rifle

1850, USA, falling block. Caliber .36, .44, Range 30/300/600, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d6, 2d8, STR d6, Very rare. Notes: Because of the automatic priming system, a Natural 1 on the Shooting roll results in a misfire. The Model 1850 Carbine is Caliber .54, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10.

On January 2, 1810 Christian Sharps was born in New Jersey, where he grew up working as an apprentice gunsmith in the town of Washington. In the early 1830s, Sharps began working at Harpers Ferry Armory as a filer. Striking up a friendship with John Hancock Hall, Sharps accepted a position next door at Hall’s Rifle Works, where he began tinkering with Hall rifles by modifying their action. In 1848, Sharps was awarded a patent for a vertically-sliding breechblock activated by a trigger-guard lever. Seeking to produce a rifle of his own, in 1850 Sharps moved to Mill Creek, Pennsylvania, where he contracted with A.S. Nippes & Company to produce the first Sharps Rifle—the famous Sharps Model 1849.

Using Christian Sharps’ patented “falling block” (sometimes called “dropping block”) action, this first model set the standard for all Sharps rifles to come. To load a Model 1849, the shooter half-cocks the hammer, which frees a loading lever positioned below the trigger-guard. Pulling down the lever lowers the breech, allowing the user to manually insert a cartridge from the top of the receiver. The shooter returns the lever to close the breech. This action activates the “wheel primer” system, which automatically dispenses a percussion cap from a circular magazine located on the right side of the frame. Once the hammer is drawn to full-cock, the rifle may be fired. Unfortunately, there was no effective method to seal the breech, a problem that was to plague Sharps rifles until the advent of metal cartridges. Produced in numbers between 50–150, the Model 1849 was followed closely by the Model 1850, which traded Sharps’ wheel primer for a Maynard tape system. The Model 1850 was also produced as a .52 carbine. Marshal’s Note: The Sharps Legend

Marshal’s Note: The Sharps Legend

Over the thirty-three years they were produced, Sharps rifles and carbines developed a legendary reputation for being extremely reliable firearms capable of accuracy at extreme ranges. In 1874, Texas scout Billy Dixon famously knocked a Comanche off his horse at a range of 1538 yards using a Sharps .50-90 rifle; demonstrating why some Indians referred to the Sharps as “the rifle that could shoot today and kill tomorrow.” Characters carrying a Sharps firearm may be awarded a “crack shot” up to twice Long Range by obtaining two raises on the Shooting roll, and up to 3x Long Range with three raises. Although the lack of a gas seal certainly inhibited early Sharps models, Deadlands is all about legends, after all…

Sharps Model 1851, “Box Lock” Carbine

1852–1855, USA, falling block. Caliber .52, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8, Rare. Notes: The “Sporting Rifle” has Range 30/300/600. Sharps firearms permit “crack shots” up to twice Long Range with two raises on the Shooting roll, and up to 3x Long Range with three raises.

With A.S. Nippes unable to offer the resources needed to mass-produce his rifles, Christian Sharps left Pennsylvania to partner with the famous Robbins & Lawrence Armory and Machine Shop of Windsor, Connecticut. While at R&L, Sharps continued to refine his patent with the help of renown gunsmiths Richard S. Lawrence, William Jones, and Rollin White. Their first project was the Sharps Model 1851, the first of a series of “slant breech” carbines. This design canted the breechblock 22° backwards from Sharps’ original 90° angle, a change that is evident in the appearance of the receiver itself. The detached operating lever was also replaced with an integrated trigger-guard lever.

The Model 1851 carbine is loaded much like the first models, but features Rollin White’s “knife-edge” breechblock. The shooter half-cocks the hammer, which frees the trigger-guard lever. Pulling down the lever lowers the breech, allowing the user to manually insert a glazed-linen cartridge from the top of the receiver. The cartridge is pushed forward until the bullet seats on the rifling, which leaves a half-inch or so of the cartridge protruding from the chamber. As the shooter returns the lever to close the breech, the breechblock shears off the end of the cartridge, spilling some powder inside the chamber and ensuring the charge will explode when primed through the flash hole. Because this invariably brings some powder to the top of the receiver as the breech is closed, the shooter generally brushes it away before fully cocking the hammer. Featuring a Maynard primer tape system, the Model 1851 encases its hammer inside the lockplate. This “box lock” configuration simplifies the number of moving parts. Unfortunately, the lack of an effective gas seal presents the same leakage problem as the previous models.

A coil of Maynard tape primer fits into this empty magazine like a modern roll of caps.

Produced as a carbine and a variable-caliber sporting rifle, the success of the Model 1851 encouraged Robbins & Lawrence to form the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company, with headquarters in Hartford, Connecticut while production continued in Windsor.

Sharps Model 1852 to Model 1853, “Slant Breech”

1853–1856, USA, falling block. Caliber .52, Range 40/400/800 Rifle, 15/150/300 Carbine, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8, Uncommon. Note: Sharps firearms permit “crack shots” up to twice Long Range with two raises on the Shooting roll, and up to 3x Long Range with three raises.

In 1853, Christian Sharps departed the rifle company that bore his name, and returned to Pennsylvania to produce pepperbox pistols. Despite his departure, Robbins & Lawrence continued to carry on the tradition of high-quality Sharps rifles. The Model 1852 carried over the angled breech of the Model 1851, highlighting it even further by introducing a relief-contoured “slanted breech” on the frame. The Maynard tape was replaced by Lawrence’s patented “pellet primer” system. When the trigger drops the hammer, a tiny primer disc is flung from a 25-pellet magazine mounted near the cock. The falling hammer is timed to catch the disc in mid-air, slamming it to the nipple and detonating the mercury fulminate charge. This system was particularly useful for cavalry troopers, who were freed from mounting percussion caps while galloping on horseback. Unfortunately, the hammer did not always intercept the primer pellet, and sometimes the gun would misfire. There was also the persistent problem of gas leakage, which the new design attempted to mitigate using a sliding “bouching” sleeve in the breech. Unfortunately, this sleeve jammed after a few firings, and hot gas continued to be vented from beneath the action. Produced primarily as a carbine, the Model 1852 was also manufactured as a military rifle, a sporting rifle, and a shotgun.

Model 1853, “Beecher’s Bible,” “John Brown Carbine”

One of the most famous Sharps designs, the Model 1852 went through three variations. After the British government cancelled a major contract with Robbins & Lawrence to produce the P53 Enfield, R&L went bankrupt, and Richard Lawrence became the superintendent of the renamed and reorganized “Sharps Rifle Company.” Production was moved from Windsor to Hartford, and the Model 1853 was introduced—essentially a Hartford version of the Model 1852. The Model 1853 earned the nickname “Beecher’s Bible” after Henry Ward Beecher shipped 900 carbines to Kansas Free Soil abolitionists in crates marked “BIBLES.” The Model 1853 was the carbine used by radical abolitionist John Brown during his raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859.

|

|

Sharps Model 1855, “Slant Breech”

1855–1857, USA, falling block. Caliber .52, Range 40/400/800 Rifle, 20/200/400 Carbine, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8, Rare. Sharps firearms permit “crack shots” up to twice Long Range with two raises on the Shooting roll, and up to 3x Long Range with three raises.

The Sharps Model 1855 swapped Lawrence’s pellet priming system with Maynard primer tape. It also featured a “gas check,” a platinum-alloy ring that expanded in the breech face to form a gas seal. Developed by Hezekiah Conant of Connecticut, this much-needed obturation system was purchased by the Sharps Rifle Company for $80,000. Interestingly, about fifty Model 1855 “Navy” Rifles were produced with Rollin White’s “self-cocking” system, in which operating the lever automatically cocked the hammer.

The .577 caliber Model 1855 “British” carbine with sling bar and ring

The Model 1855 was initially intended to be sold in England, and over six thousand were produced to chamber the British .577 round. Many of these saw action with Indian cavalry units, but Great Britain ultimately decided on the Westley-Richards carbine instead.

Marston Percussion Rifle

1850–1858?, USA, lever-action. Caliber .31, .36, .54 Marston, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 1d4+1d6 to 2d10, Very rare.

Known primarily for his pepperbox pistols, William W. Marston of New York designed over three hundred handsome rifles using a patented breech-loading system. The shooter loads a Marston rifle by pulling a trigger-guard lever, which slides back the breechblock bolt. A specialized cartridge is inserted through a rectangular loading gate located on the right side of the breech. This proprietary cartridge holds its charge in a blue paperboard tube affixed to a leather base. Left behind after the cartridge ignites, the greased leather disc serves as a rudimentary gas seal. The following round simply pushes the disc out the barrel, which helps clean the bore and alleviates fouling. Or, as Marston’s literature hopefully proclaims, “rifles using such cartridges never require to be swabbed out, the barrel will shine bright inside after firing a thousand shots.” Produced in a generous variety of styles and calibers, Marston rifles are handsomely checkered and engraved, their serpentine trigger-guard and elongated hammer adding to their distinctive appearance. Most Marston rifles feature dual set-triggers. Marston also produced a rare .70 caliber shotgun variant.

Produced in a generous variety of styles and calibers, Marston rifles are handsomely checkered and engraved, their serpentine trigger-guard and elongated hammer adding to their distinctive appearance. Most Marston rifles feature dual set-triggers. Marston also produced a rare .70 caliber shotgun variant.

Joslyn Carbine, “Monkey-Tail”

1855–1856, USA, hinged breech. Caliber .54, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Rare. Note: The very rare Joslyn Model 1855 Navy Rifle is Caliber .58, Range 30/300/600, DAM 1d10+1d12. In 1855, Massachusetts inventor Benjamin Franklyn Joslyn was awarded a patent for a breech-loading carbine generally referred to at the “monkey tail” carbine. The nickname is derived from the long breech-lever, which is recessed into the top of the frame behind the action. An oval ring allows the lever to be lifted upwards, revealing a smooth groove leading into the open chamber. The shooter inserts the paper cartridge and lowers the “monkey tail,” an action which pushes the cartridge into the bore and seals the breech. Capping the nipple and cocking the hammer readies the carbine for firing; the only gas seal is the machining of the breechblock. A crude gas seal was provided by steel rings in the breech-face which expanded upon discharge.

In 1855, Massachusetts inventor Benjamin Franklyn Joslyn was awarded a patent for a breech-loading carbine generally referred to at the “monkey tail” carbine. The nickname is derived from the long breech-lever, which is recessed into the top of the frame behind the action. An oval ring allows the lever to be lifted upwards, revealing a smooth groove leading into the open chamber. The shooter inserts the paper cartridge and lowers the “monkey tail,” an action which pushes the cartridge into the bore and seals the breech. Capping the nipple and cocking the hammer readies the carbine for firing; the only gas seal is the machining of the breechblock. A crude gas seal was provided by steel rings in the breech-face which expanded upon discharge.

The Joslyn is an attractive carbine, sporting a distinctive profile and brass furnishings. Produced by Asa H. Waters of Millbury, the carbine performed well during the Army Board trials of 1856–1857, placing second behind the Burnside carbine and netting an order for 1200 units. The Navy also ordered 500 rifles based on the Joslyn patent. Establishing the Joslyn Fire Arms Company in Stonington, Connecticut, Joslyn immediately began improving his design, efforts that would lead to the Model 1862 rimfire featured later in the Armory.

Burnside Carbine

1857–1865, USA, rotating block. Caliber .54 Burnside, Range 20/200/400, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon. Note: A roll of Natural 1 results in a stuck casing, requiring one action round to extract.

Designed by General Ambrose E. Burnside in 1855, this unique carbine was one of the first breech-loaded rifles to solve the problem of a leaking breech. The Burnside uses a special cartridge designed to be fired in conjunction with a percussion cap. Resembling a brass ice-cream cone, the cartridge features a tiny hole in its base and a bulge beneath the conical bullet. The hole accepts the primer spark, while the bulge is designed to form a gas seal upon firing.

After an initial run of 300 carbines featuring an internal tape-primer system and sporting a standard trigger-guard lever, the Burnside “Second Model” removed the tape system and introduced the distinctive “double trigger guard” appearance of the carbine. The operating lever is unlocked by activating a curved latch nested within the trigger guard. When the shooter pulls the lever, the breechblock tips up through the receiver to expose the breech. The shooter inserts the cartridge into the conical-shaped chamber and closes the breech, the bulge forming a seal between chamber and barrel. After the round is fired, the spent casing must be extracted by hand; however, its design resulted in a higher-than-average occurrence of stuck casings, which cavalry soldiers learned to pry out using the base of the fresh round.

Burnside’s carbine performed quite successfully, and passed through five distinct models over the course of the 1860s, eventually shifting production from the Bristol Firearms Company to the Burnside Rifle Company in Providence. The carbine was the third most popular cavalry weapon of the early War. Burnside himself had sold his interest in the Bristol Firearms Company before the War, but the success of his carbine certainly had an impact in his reputation, and helped advance his career during the early days of the conflict—at least until the Battle of the Crater!

Westley Richards Carbine, “Monkey Tail”

1858–1881, UK, breech-loading caplock. Caliber .451, Range 40/400/800, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d8, Uncommon. Note: The monkey-tail rifle has Range 80/800/1600.

In 1812, William Westley Richards established a firearms company that quickly developed a reputation for superior craftsmanship and innovative design. When his eldest son Westley Richards joined the company in 1840, Westley Richards & Co. found a creative genius who would elevate the Birmingham firm to a status equal to the “Best London” gunsmiths. A prolific inventor, in the 32 years he worked as a gunmaker, Westley Richards was awarded seventeen patents from the British government. The most famous of these was for a breech-loading system informally known as the “monkey tail.”

As with the Joslyn carbine, the whimsical nickname is derived from the gun’s elongated breech-lever, which is recessed into the top of the frame behind the hammer. As long as the hammer remains uncocked, a protruding tab allows the lever to be lifted upwards, revealing a smooth groove leading into the open chamber. The shooter inserts a felt-based paper cartridge and lowers the “monkey tail,” an action which pushes the cartridge into the bore and seals the breech. The hammer is cocked and the nipple capped, and the gun is ready for firing. As an additional safety measure to ensure the breech stays closed, the pressure from the exploding cartridge drives a piston backwards to mechanically lock the breech.

Diagram of an early monkey-tail caplock breech Diagram of an early monkey-tail caplock breech |

Richards’ final design, a 1868 cartridge prototype Richards’ final design, a 1868 cartridge prototype |

Octagonal Rifling

Richards’ innovative approach continued to his polygonal rifling technique, originally suggested by the industrialist Isambard Kingdom Brunel and developed in conjunction with Sir Joseph Whitworth, the artillery engineer who manufactured his first “sharpshooter” rifles at Westley Richards’ company. Brunel’s rifling calls for an octagonal bore that becomes increasingly more twisted as it winds from breech to muzzle. Like Whitworth’s rifling, Brunel’s has twice the twist rate of his contemporaries—a “fast” one revolution per 20 inches. Unlike the Whitworth rifle, which chambers a special hexagonal bullet to fit its crisp grooves, Richards’ rifles are designed for an undersized round which is “self-centered” by the “peculiar action of a polygon within a polygon acting at an increased pitch.” Despite using Brunel’s system, Richards asked the patent-averse Brunel if he would allow Richards to “license” the Whitworth patent. He agreed, and Richards had “Whitworth Patent” stamped on his barrels—a shrewd business move, as Whitworth’s rifles had already developed a reputation for astonishing accuracy!

Trials & Tribulations

Westley Richards monkey-tail rifles performed admirably during initial tests, displaying excellent accuracy and reliability. Not quite ready to abandon the P53 Enfield infantry rifle, the British War Office ordered two thousand 19” barrel monkey-tail carbines for the 10th and 18th Hussars and the 6th Dragoon Guards, with another nineteen thousand 20” barrel carbines intended for Yeomanry regiments and the colonial cavalry produced under license at the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield. Unfortunately, further progress was hindered by Richards’ reluctance to adapt his carbines to fire metallic cartridges, followed by a series of embarrassing mechanical failures during the Ordnance Select Committee trials of 1867-1868, the same trials that resulted in the adoption of the Snider-Enfield. Still, the outlook was far from bleak, and Westley Richards received an order for two thousand 36” barrel rifles from Montreal. Equipped with bayonets, they were intended to quell the Fenian uprisings in Canada. The company received an even more substantial order from Portugal, placing another twelve thousand monkey-tail rifles, carbines, and pistols into circulation.

Westley Richards “Match & Prize” Rifle, 39” barrel, 1858–1869

Westley Richards “Match & Prize” Rifle, 39” barrel, 1858–1869

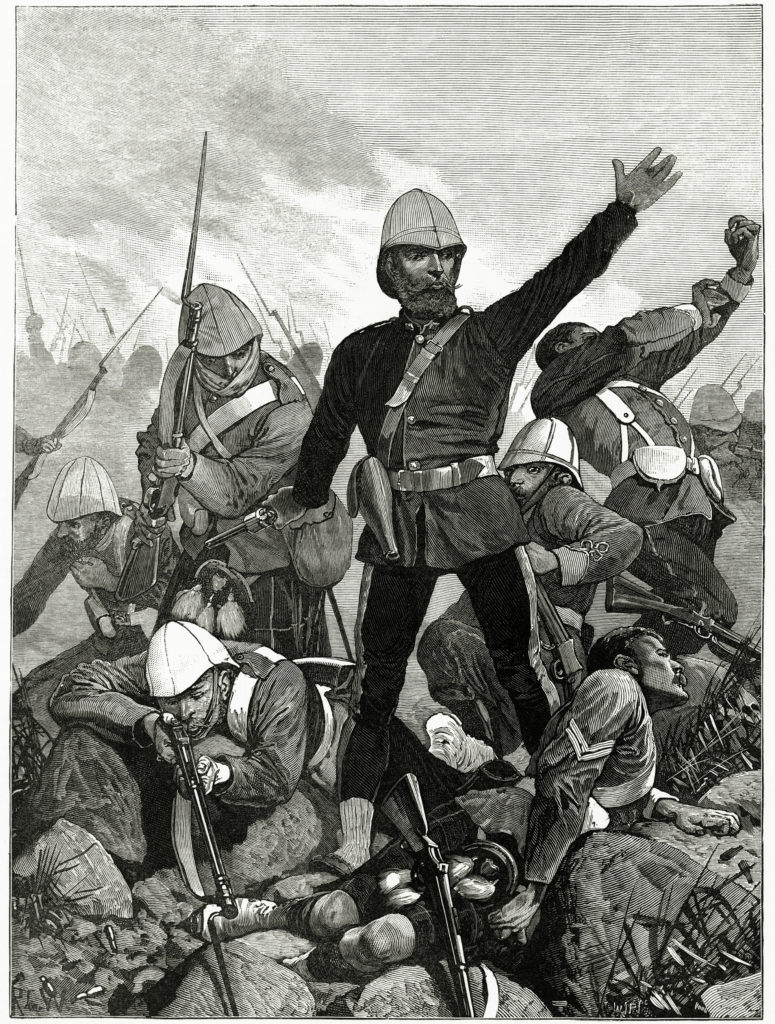

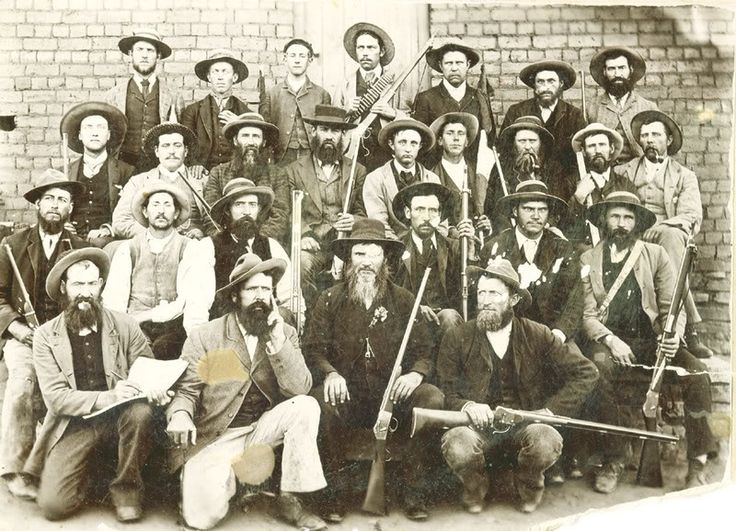

The Westley Richards monkey-tail endured even after cartridges had rendered percussion caps obsolete, and a 24” barrel carbine-rifle hybrid became popular among the Boers during the 1880s. Unable to acquire or afford metal cartridges, the Boers loaded these caplocks with homemade black-powder cartridges. They could also be muzzle-loaded in a pinch! As the Boers could testify, their accuracy easily matched the new Martini-Henry rifles carried by the British. As Westley Richards’ Web site boasts, “It is said that Boer boys learned to shoot at an early age and were not considered proficient until they could hit a hen’s egg at a 100 yds. with a Monkey Tail rifle.” Eventually, many of these monkey-tails were converted for centerfire cartridges.

Frank Wesson Rifle, “Double-Trigger,” “Two-Trigger”

1859–1888, USA, Caliber .44 rimfire, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d8, STR d6, Rare. Note: Because of their accuracy, Wesson rifles grant a +3 bonus on the Shooting roll when “aimed” as per the Deadlands rules.

Created in Worcester, Massachusetts by gunsmith Frank Wesson, this rifle was one of the first firearms designed for rimfire cartridges. The Wesson rifle featured two triggers, each encased in back-to-back trigger guards. The first trigger unbolted the barrel from the receiver to allow reloading, while the second fired the rifle. With a hefty hexagonal barrel and a stock reminiscent of a Kentucky rifle, the Wesson was fitted for calibers ranging from .22 to .44, and came in a 24” carbine, a 28” standard model, and a 34” long variant. During its run from 1859–1888, the Wesson rifle passed through several modifications, and saw much use in Kansas, Kentucky, and Illinois. The rifle was prized for its accuracy, and an 1872 “Type 3” model features an adjustable hammer that could discharge centerfire cartridges as well.

Wesson “Double” Rifle/Shotgun

1872, USA, Caliber .44 rimfire/14-gauge*, Range 50/500/1000, 20/40/60*, Capacity 2, Rate of Fire 1–2, DAM 2d8, 1-3d6*, STR d6, Very rare. Note: If “consecutive fire” is used, the Wesson “Double” does not get the +3 aiming bonus on the second shot of the action round.

One interesting but rare variant of Frank Wesson’s rimfire is the “Wesson Double,” which features two side-by-side barrels, twin hammers, and a double-trigger in the back that allows for consecutive discharge. The barrels could fire .44 rifle cartridges or 14-gauge shotgun shells.

Sharps New Model 1859 to New Model 1865

1859–1866, USA, falling block. Caliber .52, Range 40/400/800 Rifle, Range 20/200/400 Carbine, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1, DAM 2d8, STR d6, Uncommon. Note: Sharps firearms permit “crack shots” up to twice Long Range with two raises on the Shooting roll, and up to 3x Long Range with three raises.

With its 30” barrel and double set-triggers, this Model 1859 was used by Berdan’s Sharpshooters.

In 1859 the Sharps Rifle Company introduced the “New Model 1859,” returning the breech to the straight 90° angle and modifying the pellet primer system with a magazine cut-off, allowing the shooter to use traditional percussion caps. The Model 1859 also features Lawrence’s steel-ring gas seal, an improvement over the Conant method of the previous models.

Over the course of 1859–1866, the Sharps Company produced between 200,000 and 300,000 carbines and rifles based on the New Model 1859, with the New Model 1863 and New Model 1865 featuring only minor improvements. It was the most widely-used carbine in the Civil War, and was produced in a wide range of variations, from the long-range rifles famously used by Colonel Hiram Berdan’s U.S. Sharpshooters to the very rare “coffee mill” carbine, a New Model 1863 featuring a grain-grinder in the buttstock! The Model 1859 was even plagiarized by S.C. Robinson Arms Manufactory of Richmond, which made over 5000 illegal Confederate copies.

A “coffee grinder” carbine, with grain mill in the buttstock.

In 1867, the U.S. Government decided to convert many of its older Sharps models from percussion locks to cartridge-firing rifles and carbines. Working under contract, the Sharps Rifle Company converted over 30,000 New Models, with carbines fitted for .52-70 rimfire cartridges and rifles for .50-70 centerfire cartridges.

Cosmopolitan Carbine

1859–1862, USA, falling block. Caliber .54, Range 20/200/400, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Very rare. Note: The exceptionally rare Cosmopolitan Breech-Loading Rifle has a range of 40/400/800.

Early variant with “double-loop” trigger-guard

Early variant with “double-loop” trigger-guard

In 1859, Henry Gross of Tiffin, Ohio received a patent for a rifle using a simple falling-block mechanism. Featuring a two-trigger configuration enclosed by a “double-loop” trigger-guard, the rear trigger unlatches the trigger-guard lever, which is pulled down to drop the breechblock. A separate breech-cover opens to expose the chamber, with grooves guiding the insertion of the paper cartridge. The lever is returned, a percussion cap placed on the nipple, and the hammer is fully cocked. The first version of the patent was produced by the Cosmopolitan Arms Company in Hamilton, Ohio, an armory owned by Edward Gwyn and Abner C. Campbell. About 1200 “Cosmopolitan” carbines and 100 rifles were produced, many exhibiting variations, with the serpentine hammer and trigger-guard growing increasingly more curvaceous and elegant.

“Contract Type” with “grapevine” trigger-guard and serpentine hammer

“Contract Type” with “grapevine” trigger-guard and serpentine hammer

In 1862 the Cosmopolitan Arms Company contracted to produce 1140 carbines for the state of Illinois. Many of these carbines were used by the 6th Illinois Cavalry during Grierson’s famous raid during the Vicksburg campaign. The Cosmopolitan was generally considered an effective weapon, but the absence of a wooden forestock made the heated metal of the carbine difficult to hold after repeated firings. Although the leaf-and-slider rear sight was graduated to 700 yards, the carbine was not as accurate as the Sharps, and its lack of bayonet fixture rendered it useless for potential mêlée.

Ethan Allen Drop Breech Rimfire Rifle, “Falling Block Rifle”

1860–1871, USA, falling block. Caliber .22 to .44 rimfire, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d4 to 2d10, STR d6, Rare. Note: Because of the many variations of this rifle, players wishing to equip an Ethan Allen must specific caliber, length, and options.

This rifle from prolific New England gunsmith Ethan Allen uses a simple falling-block mechanism. The shooter unlocks the trigger-guard lever by pressing a catch at the rear of the trigger-guard. Pulling down the lever lowers the breechblock to expose the bore, an action that pulls out a spent casing using spring-loaded extractor. A rimfire cartridge is inserted into the chamber and the lever is returned to close the breech. What makes the Ethan Allen rifle particularly interesting is the rear sight-lever mounted on the left side of the frame. The shooter dials in the range using 100-yard increments by rotating a pointer to the appropriate setting, which correspondingly changes the elevation and angle of the rear sight.

Produced in quantities estimated between 2000-2500, the Ethan Allen rifle has many variations, chambered for .22, .32, .38, and .44 caliber, sporting barrels between 23 inches and 28 inches in length, and available in “superior woodwork.” Although most models possess an iron frame, a few Ethan Allen rifles are framed in brass. Some were later converted to .44 centerfire, with the shooter able to reconfigure the gun by simply shifting the firing pin in the assembly. As a final option, the Ethan Allen is a “take-down” rifle, with the barrel and chamber assembly easily removed and swapped for a different bore size!

Smith Carbine

1861–1865, USA, break-action. Caliber .54, Range 15/30/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon. Notes: A roll of Natural 1 results in a stuck casing, requiring one action round to extract. A critical failure results in severe fouling, requiring 1d4 action rounds and a Repair roll to fix.

Designed by Doctor Gilbert Smith of Buttermilk Falls, New York, the Smith carbine fires a unique .50 unprimed cartridge made from India rubber; this rubber expands upon firing to form a temporary gas seal. To load the carbine, the shooter pushes a take-down lever located in front of the trigger, which pushes up a brass bar to lift the topstrap and break the barrel at the breech. After the rubber cartridge is loaded, the breech is closed, a percussion cap is placed on the nipple, and the hammer is fully cocked. When the hammer detonates the percussion cap, the charge is transmitted through a hole in the base of the rubber cartridge. When the rifle is broken open for reloading, the spent casing must be manually extracted.

Paper cartridge and rubber cartridge

With over 30,000 Smith carbines produced by the American Machine Works of Springfield and the Massachusetts Arms Company of Chicopee Falls, Doctor Smith’s unusual gun was one of the most commonly used carbines of the early Civil War. Unfortunately, the rubber cartridges proved problematic for several reasons. Not only was India rubber difficult to obtain during the War, but melted or shredded rubber fouled the carbine very quickly, making the Smith notoriously difficult to clean. Substitute cartridges made from gutta-percha were difficult to extract, while paper or foil substitutes failed to properly obturate the breech. As less finicky carbines such as the Sharps and Spencer became available, the Smith was gradually phased out, and surplus Smiths were sold off at bargain prices. The Smith carbine experienced one last hurrah in 1866, when obsolete Smiths were purchased by the Fenian Brotherhood for their ill-fated invasion of Canada.

Gallager Carbine

1861–1865, USA, break-action. Caliber .54, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon. Notes: A roll of Natural 1 results in a stuck casing, requiring one action round to extract. A critical failure results in severe damage to the actuating lever or gun barrel, requiring a workshop and a Repair roll to fix.

Designed by South Carolinian Mahlon J. Gallager, this carbine was manufactured in Philadelphia by Richardson & Overman. With over 17,000 produced for the Union army, it was a common firearm in the early days of the War, but a deeply unpopular one. The Gallager uses an unprimed cartridge made out of paper, foil, or brass. To load the carbine, the shooter unlatches the trigger-guard operating lever, which pushes the barrel forward and tilts it down. The cartridge is inserted into the open bore, and returning the lever closes the breech. Because the end of the barrel is beveled to snugly fit a socket in the frame, a rudimentary gas seal is established when the action is closed. A percussion cap is placed on the nipple, the hammer is fully cocked, and the carbine is ready to fire. Unfortunately, the Gallager lacks an extraction mechanism, so when using a brass cartridge, the empty shell must be removed by hand. These cartridges have the tendency to remain stuck in the fouled action, forcing the shooter to pry out the cartridge using a knife.

The problems with the Gallager carbine were not constrained to its difficulty with extraction. Declared by some officers as “unfit for service,” the gun was shoddily made, and suffered from a wide range of misfortunes. The fragile loading lever would jam or simply break off, screws would mysteriously rattle loose from the frame, and the barrel was known to rupture during discharge. Although some of these problems were corrected in later models, the Gallager carbine remained an unpopular weapon.

Ballard Rifle

1861–1873, USA, falling block. Caliber .32 to .52 rimfire, Range 50/500/1000 Rifle, 25/250/500 Carbine, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 1d4+1d6 to 2d10, STR d6, Rare. Notes: Given the many variations of this rifle, characters wishing to equip a Ballard should specify the specific model and caliber. The most common caliber is .44, with the .52 Spencer 56-56 being the rarest.

In 1861, a Massachusetts machinist and inventor named Charles Henry Ballard received a patent for a falling-block action featuring only five moving parts. Like most falling-block rifles, the shooter pulls the trigger-guard lever to lower the breechblock and expose the breech face and chamber. In the Ballard system, the hammer sinks into the receiver along with the dropping breechblock. The shooter inserts a cartridge into the chamber and returns the lever, an action which half-cocks the hammer as it emerges from the receiver. To fire the rifle, the shooter fully cocks the hammer and pulls the trigger. When breech is opened for reloading, a rotating extractor automatically removes the spent casing.

Close-up of Ballard action

The first Ballard rifles were manufactured by Ballard’s employer, Ball & Williams of Worcester. Available in calibers ranging from .32 to .52, Ballard rifles sold well during the early years of the War, with the majority of .44 military rifles and carbines purchased by Kentucky. However, as repeaters began supplanting single-shot rifles, diminishing returns forced the Ballard patent to exchange hands, and production was shifted to consecutively smaller manufacturers. In 1874, the patent was purchased by John Marlin, who ushered the Ballard rifle into its most illustrious and well-known form. These “Marlin-Ballard” rifles are described later in the Armory.

This rare Ballard Civil War carbine fires the .52 caliber Spencer 56-56 rimfire cartridge.

U.S. Model 1858 Carbine, “Starr Carbine”

1862–1865, USA, front-hinged rotating block. Caliber .555-62-444, Range 20/200/400, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon.

In 1858, Ebenezer T. Starr of the venerable Starr Arms Company of Yonkers, New York, successfully sold his design for a single-shot, breech-loading carbine to the U.S. government. Designated the U.S. Model 1858 Carbine, the “Starr Carbine” uses a variant of a falling-block action. The shooter loads the weapon by placing the side-hammer at half-cock. The trigger-guard operating lever is pulled down, which pivots the breechblock downward and exposes the end of the barrel. A linen cartridge is inserted, and the shooter closes the breechblock by returning the lever. The end of the barrel is machined to slide into an annular brass groove in the face of the breechblock, forming a gas seal. A percussion cap is added, and the hammer is placed at full-cock.

The Starr carbine performed well during initial Army trials. Most officers found it superior to the Gallager, and because Starr’s “pivoting” breechblock involves less block-to-frame contact than Sharps’ vertically-dropping breechblock, the Starr seemed a sturdy alternative to the more expensive Sharps. Unfortunately, troops in the field had a different experience, and reported that the Starr carbine was prone to “hanging fire” at critical moments—the percussion cap would detonate, but the propellant charge failed to ignite! An investigation discovered that the problem was not with the gun, but with the ammunition. Some troops had been issued cartridges intended for the Sharps carbine. Because the Starr has a longer chamber than the Sharps, the shorter Sharps cartridges were not always catching the primer charge. By the time the problem was identified, the Starr had already developed a reputation for unreliability, and it never achieved the popularity it deserved.

U.S. Model 1865 Carbine, “Model 1865 Starr Carbine”

1865, USA, front-hinged rotating block. Caliber .56-50 Spencer (.512 bullet), Range 30/300/600, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Rare.

In 1865 Ebenezer Starr redesigned his carbine to fire the .56-50 Spencer rimfire cartridge. Historically, the U.S. Ordnance Bureau ordered five thousand Model 1865 carbines; but Lee’s surrender led to the drying up of many government arms contracts, and the Starr Arms Company went out of business two years later. Unfortunately, Ebenezer Starr fared no better in Deadlands 1876, and perished along with his family during the Plague Year of 1868.

Morse Carbine

1862–1865, SCA, hinged breechblock. Caliber .50 Morse centerfire, Range 30/300/600, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Rare.

In 1858, George Washington Morse, the nephew of Samuel F.B. Morse, received a patent for a simple breech-loading action designed to chamber an experimental centerfire cartridge. Looking for a way to convert old muzzle-loaded rifles into breech-loaders, the U.S. government adopted Morse’s design and began producing conversions at Springfield and Harpers Ferry. When South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter, the Louisianan sided with the Confederacy, and Morse was appointed the superintendent of Nashville Armory. After Harpers Ferry Armory was captured by the Virginia militia, Morse requested the machines used to make his conversions, and Nashville began producing parts for a new “Morse carbine.” Federal advances into Tennessee pushed Morse to Atlanta, where he completed his design and began demonstrating prototypes. General Sherman’s march into Georgia forced a second evacuation, this time to Greenville Armory in South Carolina. In 1864, Morse received an order to equip the South Carolina State Militia with one thousand new centerfire carbines.

Like many Confederate gunsmiths, Morse made extensive use of brass, which requires less resources and is easier to craft by unskilled laborers. Featuring a brass frame, receiver, and furnishings, each Morse carbine was issued with an ammo belt that contained twenty-four brass cartridges secured in individual tin tubes. The carbine is loaded from the top, with the shooter lifting a lever to raise breechblock and expose the chamber. A .50 caliber brass cartridge is inserted into the chamber, the breechblock is pushed down, and a centrally-mounted cocking spur is drawn to the firing position. When the trigger is pulled, a firing pin strikes the center of the cartridge and discharges the round.

One of the only Confederate weapons to use metal cartridges, the Morse Carbine was an intriguing addition to the Southern arsenal. George W. Morse actually sued the United States government after the War, believing they had copied his brass cartridges for use with Northern carbines. In Deadlands 1876, Morse continued to produce Greenville carbines until 1865, when he returned to Nashville after it was “liberated” by Cleburne and Hood. George W. Morse currently serves as superintendent of the Nashville Armory, where he devotes his creative energies to the manufacture of blue powder cartridges.

Joslyn Model 1862 Carbine

1862–1863, USA, swinging breechblock. Caliber .54 “Joslyn” rimfire, Range 25/250/500, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Rare.

With his “monkey tail” carbine of 1855 earning a lucrative government contract, Benjamin Franklin Joslyn turned to developing a new carbine chambered for metallic cartridges. The result was the Model 1862 carbine, produced at the Joslyn Fire Arms Company in Stonington. To load the upgraded model, the shooter opens the breechblock “cap” using a knob mounted on its right side. Shaped like a half-moon, the cap swivels up and flips to the left, exposing the bore. The cartridge is inserted and the cap closed. This action activates a small, wedge-shaped blade which pushes the round into the chamber. The side-hammer is cocked, and when the trigger is pulled, it falls upon a spring-mounted firing pin at the rear of the cap. When the breechblock is opened for reloading, the bladed wedge catches the cartridge by its base and extracts the spent casing.

Antique Joslyn Model 1862 with breech opened. Note the wedge-shaped extraction blade and the spring-loaded firing pin.

The Joslyn Model 1862 is a handsome firearm, featuring a case-hardened lockplate, blued barrel, and brass furnishings including barrel band, trigger-guard, and buttplate. Joslyn received a government order for 20,000 of the carbines, but only 2200 were completed before he replaced them with the upgraded 1864 pattern.

Joslyn Model 1864 Carbine

1863–1865, USA, swinging breechblock. Caliber .56-52 Spencer (.512 bullet), Range 25/250/500, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon. Note: The very rare Joslyn “Springfield” rifle is Caliber .50-60-450 rimfire, Range 40/400/800, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10.

Charged with fulfilling a substantial government order for 20,000 carbines, Joslyn continued improving his design as his Stonington factory slowly developed its capacity for mass production. After introducing a few transitional models, Joslyn settled on the “Model 1864” pattern, chambered for the .56-52 Spencer cartridge currently in favor with the U.S. military. The friction lock of the Model 1862 was replaced by a more durable spring-lock, and a gas vent was added to the top of the breech cap. The brass buttplate was replaced with iron, and the firing pin was safeguarded from accidental jarring by the addition of a protective metal shroud.

Charged with fulfilling a substantial government order for 20,000 carbines, Joslyn continued improving his design as his Stonington factory slowly developed its capacity for mass production. After introducing a few transitional models, Joslyn settled on the “Model 1864” pattern, chambered for the .56-52 Spencer cartridge currently in favor with the U.S. military. The friction lock of the Model 1862 was replaced by a more durable spring-lock, and a gas vent was added to the top of the breech cap. The brass buttplate was replaced with iron, and the firing pin was safeguarded from accidental jarring by the addition of a protective metal shroud.

The Model 1864. Note the shroud around the firing pin.

In early 1865, three thousand Joslyn breech mechanisms were sent to Springfield Armory to be assembled into .50-60-450 military rifles—the first breech-loading rifles to be produced at Springfield. Historically, the end of the Civil War assured that many Joslyn carbines and Joslyn “Springfields” would never enter service. With only half the order of 20,000 actually purchased, the U.S. Government cancelled the contract, claiming that Joslyn’s carbines failed to meet their specifications. Many of the remaining carbines were sold privately, while the rifles were shipped to France for the Franco-Prussian War. The Joslyn Fire Arms Company went bankrupt in 1868, and Joslyn became tied up in litigation against the government. In the Deadlands timeline, B.F. Joslyn perished during the Plague Year of 1868, putting an end to the Joslyn Fire Arms Company just as assuredly as the historical epidemic of peacetime budgeting.

Gwyn & Campbell Carbine, “Grapevine Carbine,” “Union Rifle”

1863–1864, USA, falling block. Caliber .54, Range 30/300/600, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, Uncommon.

Type I Gwyn & Campbell, similar to the “contract” Cosmopolitan

Type I Gwyn & Campbell, similar to the “contract” Cosmopolitan

The Gwyn & Campbell carbine is essentially the continuation of Henry Gross’ “Cosmopolitan” carbine of 1859. After fulfilling their Illinois contract, the Cosmopolitan Arms Company further refined Gross’ patent by simplifying the action into a more traditional falling block. Similar to the “contract” Cosmopolitans, the Gwyn & Campbell sports an elegant serpentine hammer and trigger-guard, and is unlocked by a rear-mounted release trigger. Sometimes called the “Grapevine” carbine because of its curvaceous trigger-guard, it’s also referred to by the phrase stamped into the right side of the frame: “UNION RIFLE.” A later “Type II” model flattened the serpentine hammer, shortened the loading lever, and replaced the rear trigger with a simple unlocking catch.

Produced almost exclusively for military contracts, over 8000 Gwyn & Campbell carbines found their way into Union cavalry units ranging from Illinois to Tennessee. They still suffered from the same problems of the Cosmopolitan—no bayonet fittings, no forestock, and no effective gas seal.

Type II Gwyn & Campbell close-up. Note the “UNION RIFLE” stamp.

Springfield “Trapdoor” Conversions

1865–1870, USA, hinged breechblock. Caliber .50-70, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Common.

In the late-1850s, the U.S. Government began exploring options to convert their obsolete surplus of muzzle-loaders into modern breech-loaded rifles. Contracts were awarded to a wide variety of designs, many of which were implemented at Harpers Ferry and Springfield as well as private workshops. From William Mont Storm’s rimfire conversions at Harpers Ferry to Whitneyville’s “Phoenix” conversions of the Model 1861/63, there was plenty of work to go around. Starting in 1865, Springfield Master Armorer Erskine S. Allin began tinkering with Model 1861 rifled muskets, machining a “trapdoor” into the rear barrel and installing a hinged breechblock. Open and closed with a simple thumb-latch, this “trapdoor” gave the next generation of Springfields their enduring nickname. As the years passed, Allin made several modifications to his design, simplifying the action and settling on copper .50-70 centerfire cartridges.

This Model 1866 “Trapdoor” Springfield still has the 1864 lockplate.

This Model 1866 “Trapdoor” Springfield still has the 1864 lockplate.

Allin’s Springfield conversions are referenced by their current model number followed by the “trapdoor” designation, such as the Model 1866 “Trapdoor” Springfield, which is a Model 1863 percussion rifle converted to fire centerfire cartridges. More informally, Allin’s conversions are sometimes referred to as “First Allin,” “Second Allin,” and so forth.

New Canaan Dibble & Browning Breech Rifle, “Nauvoo Springfield”

1866–1877, Deseret, hinged breechblock. Caliber .50-70, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Uncommon.

Distinctively elegant, costly to produce, and extremely well-crafted, the Dibble & Browning Breech Rifle set the standard for all future firearms manufactured at Deseret’s New Canaan Armory. Based on Erskine S. Allin’s “Trapdoor” Springfields, the rifle was the armory’s first project, and was intended to arm the growing Nauvoo Legion against hostile Indians and intransigent Unionists. Under the direction of Mormon gunsmiths Jonathan Browning and Orator II Dibble, New Canaan’s armorers designed an “improved” version of Allin’s conversions from the ground up, enhancing the rifling and reducing the length of the forestock. They also case-hardened the hammer and breech, engraved the receiver with detailed scrollwork, and generously checkered the walnut stock. Each rifle features a numbered metal stamp reading, “Holiness to the Lord—Our Preservation.”

Distinctively elegant, costly to produce, and extremely well-crafted, the Dibble & Browning Breech Rifle set the standard for all future firearms manufactured at Deseret’s New Canaan Armory. Based on Erskine S. Allin’s “Trapdoor” Springfields, the rifle was the armory’s first project, and was intended to arm the growing Nauvoo Legion against hostile Indians and intransigent Unionists. Under the direction of Mormon gunsmiths Jonathan Browning and Orator II Dibble, New Canaan’s armorers designed an “improved” version of Allin’s conversions from the ground up, enhancing the rifling and reducing the length of the forestock. They also case-hardened the hammer and breech, engraved the receiver with detailed scrollwork, and generously checkered the walnut stock. Each rifle features a numbered metal stamp reading, “Holiness to the Lord—Our Preservation.”

More expensive than a Springfield conversion, the so-called “Nauvoo Springfield” quickly developed a reputation as being the superior rifle. During the latter part of the Second Utah War, many U.S. soldiers traded their authentic Springfields for Mormon “copies” acquired on the battlefield or purchased from apostate smugglers. Having gone through several minor iterations in its decade-long existence, the Dibble & Browning will finally cease production in 1877 as one of the stipulations of U.S. diplomatic recognition of Deseret.

Snider-Enfield

1867–1901, UK, latch lock. Caliber .577 Boxer, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Common.

Born in Georgia and residing in Philadelphia, American inventor Jacob Snider developed a breech-loading mechanism in the early 1860s known as the “latch lock” system. To load the rifle, the shooter unlocks the breechblock by half-cocking the hammer. Hinged on the right side of the receiver, the breechblock is opened by thumbing a latch projecting from its left side, somewhat like flipping open the lid of a treasure chest. The shooter pushes a new round into the chamber and closes the breech. After the hammer is fully cocked, the rifle is ready to fire. Once the breechblock is opened again, it’s pulled backwards to extract the spend casing, which is tipped out of the breech by sharply rotating the rifle.

Looking to convert the Pattern 1853 Enfield from a muzzle-loader into a breech-loader, the British government adopted Snider’s latch lock system and began producing a conversion model known as the Snider-Enfield Mark I. By the time the Snider-Enfield Mark III was introduced, the rifle was being assembled entirely from new components. Fitted for Edward Boxer’s .577 brass cartridge, the Snider-Enfield was standard UK issue until it was replaced by the Martini-Henry in 1874. Unfortunately for Jacob Snider, the British government failed to compensate him to his satisfaction. Historically, Snider died in penury in London while trying to obtain his fair share; in Deadlands, his fate takes a different but no less tragic turn, as described in the entry for the P67 “Dixie” rifle.

Macon Pattern 1867 Infantry Rifle, “Dixie”

1867–present, CSA, latch-lock. Caliber .577 Dixie, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Common. Note: The “Cherokee Rose” variant is Caliber .50, Range 70/700/1400, DAM 2d10.

The first infantry rifle mass-produced at Georgia’s New Macon Armory, the P67 “Dixie” is the Southern cousin of the Snider-Enfield put into production by the United Kingdom the previous year. After Jacob Snider began experiencing financial difficulty with his British paymasters, Samuel Griswold invited him to New Macon to modify his latch-lock system for a new Confederate rifle. Despite Snider’s longtime Yankee affiliations, he negotiated a lucrative contract and returned to his native state with the title of “Master Armorer.”

Given the nickname “Dixie” by Snider himself, the P67 operates much like the Snider-Enfield. To load the P67, the shooter unlocks the breechblock by half-cocking the hammer. Hinged on the right side of the receiver, the breechblock is opened by thumbing a latch projecting from its left side, somewhat like flipping open the lid of a treasure chest. The shooter pushes a new round into the chamber and closes the breech. After the hammer is fully cocked, the rifle is ready to fire. Once the breechblock is opened again, it’s pulled backwards to extract the spend casing, which is manually ejected from the rifle. (Because most Confederate soldiers do this by turning the Dixie upside-down and shaking it, Union troops nicknamed the rifle the “Reb Shaker.”) A sturdy but handsome firearm, the P67 features a round barrel and an oiled walnut stock stamped with the “Macon Magnolia” trademark. A rear “ladder sight” allows for respectable accuracy at long ranges. Although the frame of the P67 is made of iron, it sports a brass trigger guard and patchbox, and the Mark II pattern added a brass muzzle-cap and distinctive “magnolia leaf” latch-tab. As might be expected, there are several variants of the P67, including a 22” carbine and a 29” sharpshooter model known as the “Cherokee Rose” (Cal .50, Range 70/700/1400, DAM 2d10). Because the P67 chambers a Southern version of the brass .577 Boxer round, the Dixie avoids the jamming problems of the Springfield 1873; however, it’s more expensive to produce, and the rounds are difficult to find outside the CSA.

Macon Pattern 1867 Mark IV Sharpshooter Rifle, “Snider Commemorative”

1877, CSA, latch-lock. Caliber .45-50 Loveless-Howell, Range 100/1000/2000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Very rare. Note: The “Nashville” rifling gives the Snider Commemorative a +3 bonus on the Shooting roll when “aimed” as per the Deadlands rules.

Jacob Snider’s story has a tragic coda. When visiting Confederate-occupied Philadelphia in 1876, Snider was abducted by the Minutemen and crucified on a lamppost, a P67 Dixie used as the cross-piece and a placard reading “Traitor” hanging from his neck. Shortly thereafter, the New Macon Armory announced plans to produce a 10-year anniversary model of the P67. Called the “Snider Commemorative,” the rifle will be chambered for the Loveless-Howell .45-50 blue powder round and bored with Harlan Stone Counterfly’s new “Nashville” rifling. Limited to a run of 1000, each rifle will be hand-crafted with a unique “Cherokee Rose” pattern on the stock, and come packaged in a maple carrying case containing a detachable brass 6x scope with Caloosahatchee lenses.

Modell 1867 Werndl-Holub, “Werndl”

1867–1918, Austria-Hungary, rotating drum. Caliber 11.15x42mmR (.44 inches), Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d8, STR d6, Uncommon.

Developed by Josef Werndl and Karel Holub at Werndl’s factory in Steyr, this rifle replaced the muzzle-loaded Lorenz rifle and its Wänzl cartridge conversions. The rifle is loaded using a rotating drum-action. The shooter half-cocks the hammer, which unlocks a rotating “drum” sitting in the breech. A leaf-shaped latch on the right side of the drum lid is rotated from left to right, which opens the drum and allows the shooter to insert a round into the chamber. Because this action reminded Werndl of opening a Catholic tabernacle, he nicknamed the system the Tabernakelverschluß, or “Tabernacle breech.” Once the drum is rotated closed, a full-cock of the hammer readies it for firing. The Werndl has a surprisingly robust trigger pull, requiring some ten pounds of pressure to trip the hammer!

The M67 Werndl proved to be a very reliable gun, more sturdy and accurate than the Prussian needle rifle it was designed to oppose. Werndl himself once impressed a reporter by firing the rifle, throwing it from the second-story window of his factory, retrieving it, firing it again to demonstrate its accuracy, and then repeating the process several more times! The Werndl remained in service for two decades, after which it was replaced by the M1886 Mannlicher Gewehr, a straight-pull bolt-action repeater.

The M67 Werndl proved to be a very reliable gun, more sturdy and accurate than the Prussian needle rifle it was designed to oppose. Werndl himself once impressed a reporter by firing the rifle, throwing it from the second-story window of his factory, retrieving it, firing it again to demonstrate its accuracy, and then repeating the process several more times! The Werndl remained in service for two decades, after which it was replaced by the M1886 Mannlicher Gewehr, a straight-pull bolt-action repeater.

Remington Single-Shot Breech-Loading Carbine, “Split Breech”

1865–1866, USA, rolling block. Caliber .46 rimfire for Type I, .56-50 Spencer (.512 bullet) for Type II, Range 25/250/500, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 1d8+1d10 or 2d10, Common.

Remington Type II “Split-Breech” Carbine

Remington Type II “Split-Breech” Carbine

In 1858 Joseph Rider, a Pennsylvania shoemaker living in Ohio, was awarded a patent for a double-action percussion revolver. Selling the rights to E. Remington & Sons, Rider relocated to Newark and opened a jewelry store, where he continued to work with Remington on various “Remington-Rider” firearms. In December 1863, Rider patented a rifle mechanism in which a split breechblock opened and closed the end of the barrel by rotating around the cocking spur. Remington purchased the patent, and for good measure acquired a similar “split breech” patent awarded twelve months earlier to Leonard Geiger of Hudson, New York. Rider made a few improvements to the design, and Remington accepted an order for 1000 carbines from the U.S. Ordnance Department. With their Ilion facilities tied up producing “New Model” revolvers, “Zouave” rifles, and contract Springfields, Remington turned to Savage Revolving Arms, who accepted on the condition that the order was increased to 10,000. Remington took the risk, and it paid off handsomely. The result is the Remington “split breech” carbine, the predecessor to the rolling block firearms that would dominate the market for the next half-century.

To load the “split breech” carbine, the shooter places the hammer at full-cock and rolls back the breechblock using a split tab. This action also extracts a spent casing. A cartridge is inserted into the chamber, the breechblock is returned, and the carbine is ready to fire.

|

|

The Remington “split-breech” carbine was manufactured in three distinct runs. The original Type I model was chambered for the .46 rimfire cartridge. After the government adopted the .56-50 Spencer round, the need for a larger action produced the heftier frame of the Type II. Historically, the end of the War caused many of these Type II carbines to languish in storage, where they were bought back by Remington and sold to France for use in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. Savage returned the machinery and dies to Ilion, and Remington introduced the Type III, a sporting carbine chambered for multiple calibers and featuring a variety of wooden stocks. In the world of Deadlands, the Type II was produced in twice the historical numbers, and saw heavy use during the War. The carbines sold to France were simply pulled from the extended production run. The Type III does not exist.

Remington Rolling Block Rifle

1867–1934, USA, rolling block. Caliber .22 to .50-70, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d4 to 2d10, STR d6, Common. Notes: When firing a Remington rolling block, the shooter adds a d4 die to his Shooting roll. This is not an extra wild die; but a critical failure only occurs if the shooter rolls three ones (his Shooting die, his wild die, and the extra d4).

Working with E. Remington & Sons, Joseph Rider continued to refine his “split-breech” design, finally arriving at Remington’s famous “rolling block” action in 1866. One of the most simple, reliable, and durable forms of action, the rolling block would help define Remington for the next few decades, and would make Joseph Rider the wealthiest man in Newark. Rider separated the cocking spur from the breechblock, positioning the hammer just behind and below the “rolling” breechblock. Loading the weapon is simple. After fully cocking the hammer, the shooter pulls down a tab mounted in front of the hammer, rolling the breechblock open and exposing the rear end of the barrel. This action also extracts a spent casing. A metal cartridge is inserted into the chamber, and the breechblock is rolled shut, enabling the rifle to be fired.

|

|

| Breech closed—note the “rolling” breechblock | Breech open and ready to load! |

From rolling-block conversions of Springfield muskets produced at Remington’s Ilion factory to single-shot Remington handguns, millions of firearms employ Remington’s rolling block action. A modified form of rolling block is even used to throw harpoons from the Ingersoll Life-Line Gun of 1885! Marshals and players are free to research specific types of rolling block firearms, with Remington “sporting” rifles being the most prevalent in nineteenth-century gun shops.

Remington No. 1 Long-Range “Creedmoor” Rifle, 1873–1890

Remington Model No. 1-1/2 Sporting Rifle, 1888–1897

Remington Model No. 1-1/2 Sporting Rifle, 1888–1897

Model 1871 Remington-Army Rolling Block, “Springfield Rolling Block”