Muzzle Pistols

- At February 11, 2017

- By Great Quail

- In Armory, Deadlands

0

0

Handguns Part I. Muzzle-Loading Pistols

Handguns vs. Rifles

For the most part, the history of handguns followed the same evolutionary development as rifles. Muzzle-loading flintlocks were replaced by percussion caplocks in the mid-nineteenth century. These muzzle-loading pistols were supplanted by breech-loading pistols and revolvers, with the advent of metal cartridges after the Civil War leading the way to the modern era. This basic history is detailed in the “Rifles” section of the Deadlands Armory. The only significant deviation in their shared history lies with repeaters. In the world of long arms, lever-action rifles became the standard form of repeater after the Civil War, while revolvers quickly dominated the handgun market.

Nomenclature: Handguns, Pistols, & Revolvers

The term “handgun” is a broad term, covering everything from derringers to revolvers to modern semi-automatics. For that reason, it’s used in these documents as a universal term for all hand-held firearms. Nevertheless, the word “handgun” has a distinctly modern feel—the more appropriate nineteenth-century word is “pistol.” However, as revolving-cylinder pistols began to grow in popularity, the term “revolver” gained currency, and “pistol” began to signify the single-shot firearms of the previous era. For this reason, the Armory calls revolving pistols “revolvers,” and reserves the term “pistol” for handguns that do not use revolving cylinders. This is an arbitrary distinction: a revolver is still a pistol, and may be referred to as such by other sources!

Muzzle-Loading Pistols

Produced in a time before modern manufacturing techniques, muzzle-loading pistols are found in a wide variety of styles across the centuries, from ornate dueling pistols hand-crafted by Flemish masters to military pistols assembled in bulk at Federal armories. Fortunately for the purposes of Deadlands, all muzzle-loading function identically, with the exception of the method used to prime the charge of black powder. Putting aside early matchlocks and wheel-locks for a milieu more concerned with cavaliers and piracy, the Deadlands Armory focuses on flintlocks and caplocks.

This modern Pedersoli flintlock pistol sports a case-hardened lockplate and brass decorative work.

This modern Pedersoli flintlock pistol sports a case-hardened lockplate and brass decorative work.

Size Matters

Whether flintlock or caplock, black powder pistols are usually characterized by their size. The smallest are “muff” pistols, also known as “derringers.” Intended to be easily concealed, these pistols are described in their own section of the Deadlands Armory. Those with slightly longer barrels are known as “belt” pistols, followed by “coat” pistols, which are designed to be concealed in the carrier’s pockets. Most modern handguns would be considered “coat” pistols.

Belgian .36 caliber “muff” pistol

Belgian .36 caliber “muff” pistol

Tracing their origins to the cavaliers of the seventeenth century, the largest pistols are known as “horse” pistols, which are carried in holsters attached to the front of a rider’s saddle. For this reason, horse pistols are also known as “holster” pistols. It was common for officers or cavaliers to be issued two matched pistols, known as a “brace” of pistols. The most common type of holster pistol is the “dragoon” pistol, issued to mounted soldiers but also favored by sailors and outlaws.

Graham Turner’s painting of a Parliamentary cavalryman shows his wheel-lock pistol and saddle holster.

Graham Turner’s painting of a Parliamentary cavalryman shows his wheel-lock pistol and saddle holster.

Another common type of horse pistol is the “coach” pistol. Generally stored in a coachman’s box or stowed under the seat of a carriage, this gun is used in case of emergencies—highway robbery, for instance, or when one needs to put down a lame horse. Coach pistols eventually evolved into the famous stagecoach shotgun of the Wild West. Other descendants of coach pistol are the “pocket rifle,” often with detachable stock; the “buggy gun,” usually stowed beneath the seat of a buggy; and the “bicycle rifle,” designed to be carried under the frame of a bicycle. Such guns were intended for spontaneous target practice or hunting small game during recreational outings.

This .32 caliber buggy gun sports a 12” barrel.

This .32 caliber buggy gun sports a 12” barrel.

A World of Variety

Marshals and players wishing to equip a muzzle-loading pistol should select a particular model and assign damage according to caliber, usually either .58 or .69. Additionally, some muzzle-loading pistols possess rifled barrels, which may extend their S/E/L range by 20% in each category. There are hundreds of historical models to choose from, and countless fictional ones to cheerfully invent. Go collect them all!

A Note on Armory Chronology

The long history of muzzle-loading pistols does not lend itself to a chronological listing of mass-produced models. For that reason, the Armory below is divided into two parts. Chapter 1 describes the basic categories of muzzle-loading pistol, offering generic statistics and suggestions for usage. Chapter 2 profiles individual models and/or series, starting with the British and French efforts to standardize their respective arsenals in the early 1700s.

The Armory: Muzzle-Loading Pistols, Chapter 1. General Categories

Flintlock Pistol

1600–1820s, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .50 to .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Common. Early firearms were classified by the system used to ignite, or “prime” the charge of gunpowder propellant needed to fire the lead ball from the barrel. Beginning in the early seventeenth century, matchlocks and wheel-locks were replaced by the less cumbersome flintlock, which uses a piece of flint to spark the primer. The dominant firearm for over two centuries, flintlocks were produced all over the world by individual gunsmiths, with some of the finest examples coming from England, Scotland, France, Spain, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire.

Early firearms were classified by the system used to ignite, or “prime” the charge of gunpowder propellant needed to fire the lead ball from the barrel. Beginning in the early seventeenth century, matchlocks and wheel-locks were replaced by the less cumbersome flintlock, which uses a piece of flint to spark the primer. The dominant firearm for over two centuries, flintlocks were produced all over the world by individual gunsmiths, with some of the finest examples coming from England, Scotland, France, Spain, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire.

Despite their wide variety in size, caliber, and appearance, every flintlock pistol is fired in the same way. First, the shooter must load the pistol. A measure of gunpowder is drawn from a powder horn, or dispensed from a pre-measured cartridge of gunpowder, which is contained in a paper or linen packet that is usually bitten open. Once the gunpowder is poured into the muzzle, the shooter inserts the lead ball, which is encased in a lubricated bit of cloth called “wadding.” Pulling the ramrod from its slot beneath the barrel, the shooter tamps the ball home, ensuring firm contact with the propellant charge. The hammer is pulled to half-cock. A small pinch of gunpowder is placed into a “priming pan” on the right sideplate. The priming pan is closed to secure the primer, which brings a metal flange called the “frizzen” into striking position before the hammer. To fire the pistol, the hammer is fully cocked and the trigger pulled. This drops the flint against the frizzen, simultaneously creating a spark and opening the pan to expose the primer. The priming powder ignites, sending its charge through a “touchhole” into the chamber to explode the main charge of gunpowder. The lead ball is propelled from the barrel in a cloud of gunsmoke and burning wadding.

French Mle. 1777 Charleville flintlock pistol. The labeled parts are common to all flintlocks.

French Mle. 1777 Charleville flintlock pistol. The labeled parts are common to all flintlocks.

Flintlock pistols have extremely short ranges, and are not designed to serve as infantry firearms. They are usually fired once and tossed aside in favor of a cutlass or other mêlée weapon. Alternately, a discharged pistol may be inverted and used as a club, with the user gripping the barrel and lashing out with the metal-capped butt.

This .60 caliber flintlock is made from German silver.

This .60 caliber flintlock is made from German silver.

Dating from the early seventeenth century and used past the Napoleonic Wars, flintlock pistols were so common that many remained in circulation during the early days of the Civil War. Considered an antique by 1876, the Marshal may use the above statistics for any number of flintlock pistols, assigning an appropriate damage rating using standard caliber rules.

These matched Barbary Coast pistols are made from iron, bone, and brass, and date from the late eighteenth century.

These matched Barbary Coast pistols are made from iron, bone, and brass, and date from the late eighteenth century.

Dueling Pistols

1600–present, muzzle-loading flintlock or caplock. Caliber .50 to .69, Range 5/20/40 Smoothbore, 5/25/50 Rifled, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3 Flintlock, 1/2 Caplock, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Uncommon. Note: The superior craftsmanship of a dueling pistol confers a +1 Shooting bonus.

The most accurate and expensive muzzle-loading pistols are “dueling pistols,” produced in matched pairs and packaged in cases with identical ammunition and powder. More frequently shown off than actually fired, such pistols are considered a gentleman’s accessory, and are renowned for their ornate design. Of course, when actually called upon to fulfill their purpose, they need to be reliable and accurate, so most dueling pistols are well-crafted, featuring sturdy smoothbore barrels and chambered for a caliber appropriate to the “ten-to-fifteen paces” range. The more luxurious models have hair triggers, support spurs, platinum-ringed touchholes, and barrels of Damascus steel. Although certain duelists consider rifled barrels to be unsportsmanlike, customs vary with time and place, and rifled sets are not unknown. The only ironclad rule about dueling pistols is that a matched set must be identical in every way.

Over time, particular gunsmiths became famous for the quality of their dueling pistols, with London’s Wogdon & Barton being especially noteworthy. The manufacturing of dueling pistols persisted long after the practice became illegal, and continued to be produced as flintlocks even after caplocks became the norm—tradition, of course! Even in the technologically-advanced Maze, where the tradition of dueling has experienced a renaissance, the finest gunsmiths only produce flintlock dueling pistols.

In my game, this modern Pedersoli replica represents a fictional dueling pistol made by French expatriate Marcel Henri Le Page, master armorer of Théâtre Le Page of San Francisco. One of a matched .44 caliber set from 1871.

Volley Gun

1600–1840s, muzzle-loading flintlock or caplock. Caliber variable, Range 5/10/15, Capacity 3–6, Rate of Fire 1/1+2xCap, DAM 3d6/2d6/1d6, Rare. Notes: Damage is calculated like a shotgun, with three DAM ratings tied to S/E/L ranges. The Marshal is free to add modifiers, usually +1 DAM/barrel, depending on the configuration of the barrels.

Four-barreled volley pistol by Lea of Mansfield, 1810

Four-barreled volley pistol by Lea of Mansfield, 1810

Perhaps the most outré species of handgun, a “volley gun” boasts multiple barrels which are fired simultaneously. A single pan or percussion cap is used to prime all the barrels, whether they are sparked by individual touchholes or diffuse the explosive energy through a series of internal vents. In actuality, it is rare for every barrel to fire properly, and the powerful recoil forbids any attempt at genuine accuracy. As one might imagine, the point of a volley gun is not precision, but firepower. Volley guns are designed to clear a path in front of the shooter, and are favored by sailors, prison wardens, and bank guards. Volley guns are usually classified by the configuration of their barrels. A “duckfoot” pistol has the barrels spread in a horizontal fan. However, a circular arrangement is more common, such as the infamous Nock gun of the British Navy.

One interesting variant is the Harrington Percussion Volley Gun of 1836, which features a removable seven-chambered breechblock. When the loaded block is replaced into the breech of the gun, a single trigger pull fires all seven chambers through a seven-bored barrel.

Perhaps the most famous use of a volley gun was by Giuseppe Marco Fieschi, who used a homemade twenty-five barrel volley gun in his attempt to assassinate the French King Louise-Phillipe I in 1835. Dangerously overstuffed with buck-and-ball loads, the machine infernale worked somewhat imperfectly, killing eighteen people, lightly wounding the King, and severely injuring Fieschi when four of its barrels exploded upon discharge.

Double Pistol

1600–1840s, muzzle-loading flintlock or caplock. Caliber .25 to .60, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 2, Rate of Fire 2/5*, DAM 2d4 to 2d12, Rare. Note: A double pistol with both hammers fully cocked may be fired in two ways. The shooter may fire each barrel separately, which allows two consecutive rounds of combat followed by four rounds of reloading. Or, the shooter may quickly fire both barrels during one action round. This inflicts a –2 penalty to both Shooting rolls.

Modèle 1855 “over-and-under” double-barrel percussion pistol made at Saint-Etienne

Modèle 1855 “over-and-under” double-barrel percussion pistol made at Saint-Etienne

Sporting twin barrels, the double pistol is the black-powder forefather of the famous “howdah” gun of the late Victorian era. Whether flintlock or caplock, double pistols are produced in two basic configurations. The “over-and-under” style stacks the barrels in vertical alignment, while the “side-by-side” places them horizontally, similar to a double-barreled shotgun.

Double-barrel pistol by Mayes of Norwich, .60 caliber

Unlike its more cumbersome cousin, the volley gun, a double pistol features separate firing mechanisms for each barrel. This additional level of sophistication allows the barrels to be fired sequentially rather than simultaneously. The forward trigger discharges the upper or right-side barrel, and the rear trigger discharges the lower or left-side barrel.

Wogdon & Company side-by-side double-barrel flintlock, circa 1760

Wogdon & Company side-by-side double-barrel flintlock, circa 1760

Sword Pistol

1600–present, muzzle-loading flintlock or caplock. Caliber variable, Range 5/10/20, Capacity 1 or 2, Rate of Fire 1/3 or 2/5, DAM Pistol by caliber, Blade 1d4+STR or 1d6+STR, Rare. Note: If the blade is used prior to firing the pistol, each round of mêlée combat contributes 5% to a cumulative chance that the pistol will misfire—the ball becomes unseated, the priming powder disperses, the percussion cap drops off, etc.

The first known “sword pistols” were made in Central Europe for boar hunting, and were used to ceremoniously finish off a wounded beast. Once the idea emerged to fuse gun and blade, armorers began producing increasingly more fanciful variations, from double-barreled flintlock katars to the U.S. Navy Elgin, which introduces an eleven-inch Bowie knife to a percussion pistol.

This fine example of a pistol-katar features Shiva flanked by .45 caliber flintlocks.

This fine example of a pistol-katar features Shiva flanked by .45 caliber flintlocks.

With the pistol grip usually serving as the hilt of the blade, a sword pistol is primarily a mêlée weapon, the user discharging the pistol at point-blank range before engaging in hand-to-hand combat. Of course, the shot may be reserved for a more surprising moment, but the more vigorously the blade is used, the higher the chance of unseating a loaded ball, spilling the primer, or dislodging a percussion cap. As of 1876, sword pistols are still being produced, some of which incorporate breech-loaded guns or revolvers.

A .38 caliber percussion pistol combined with a folding knife. The barrel is Damascus steel, the hilt is German silver.

A .38 caliber percussion pistol combined with a folding knife. The barrel is Damascus steel, the hilt is German silver.

Double-Barreled Sword Pistol

One type of sword pistol that came into vogue during the mid-nineteenth century is the double-barreled sword pistol, in which a pair of matched barrels flanks the base of a grooved blade. These pistols are usually primed by percussion caps, and are fired by an elaborate mechanism concealed in the quillions of the hilt, which are pulled back to function as hammers.

This gold-plated, double-barreled .38 percussion pistol was made by Parisian gunsmith Joseph-Celestin Dumouthier.

This gold-plated, double-barreled .38 percussion pistol was made by Parisian gunsmith Joseph-Celestin Dumouthier.

Variations

Another variant of sword pistol reverses the traditional orientation by placing the barrel inside the hilt, with the muzzle poking from the pommel. Needless to say, such pistols are best loaded with the blade safely in its sheath!

This .25 caliber flintlock was manufactured by F.X. Richter.

This .25 caliber flintlock was manufactured by F.X. Richter.

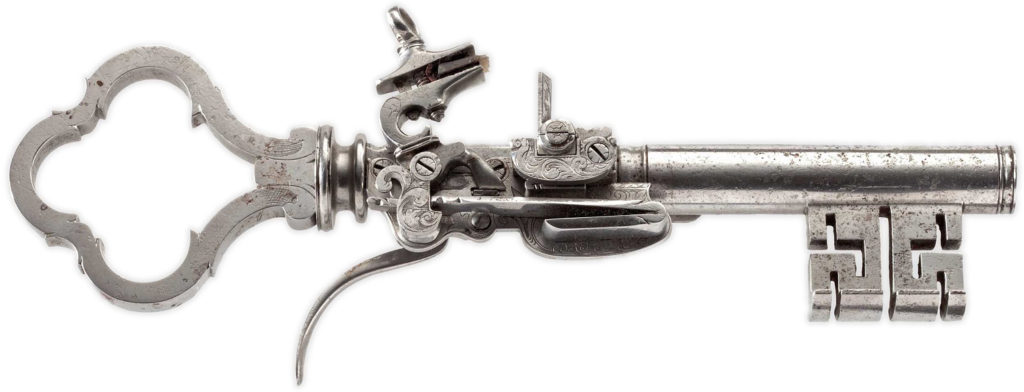

Other combinations of pistol and mêlée weapon include pinfire sword-canes, pistols sporting axe blades, and whips with pistols wrapped inside their leather handles. There is also the “key pistol,” in which a tiny pistol is concealed within a metal key!

Scottish Highland Pistol, “Doune Pistol”

1650–1810s, UK, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .52 to .60, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Very rare.

.56 caliber Highland pistol by John Jones & Company

.56 caliber Highland pistol by John Jones & Company

In 1647, a Flemish blacksmith named Thomas Caddell settled in the Scottish town of Doune, a market village located at a crossroads near Stirling. Eventually turning to firearms, Caddell began producing a unique type of flintlock pistol that would soon be known as the “Highland pistol.” Forgoing wood for pattern-welded steel, Caddell’s all-metal pistol lacked a trigger-guard; featured a “button” trigger, fluted breech, and flared muzzle; and terminated in a distinctive ram’s-head butt framing a small knob. This knob could be unscrewed to reveal a “pricker,” a pin used to clean a fouled touchhole. Caddell’s pistols became quite popular among Scotsmen, and soon Doune became the center of a flourishing arms industry. Caddell himself founded a factory that lasted for five generations, and many of his gunsmiths settled locally to open their own gun shops. The most famous of these were Alexander Campbell, Christie & Murdoch, and Macleod of Perth, all of whom developed individual variations on the Highland style. Indeed, the style was so popular that soon “Highland” pistols were being produced outside of Scotland.

|

|

When Scottish regiments were raised in the mid-eighteenth century, soldiers customarily carried a musket and a broadsword, and wore a Highland pistol strapped under their left arm. With little practical use, these pistols became increasingly more ornamental, sporting elaborate engravings and inlaid with precious metals and stones. Some were fashioned from brass, bronze, or German silver instead of steel. With the price of Doune pistols steadily increasing, regiments began turning to less costly alternatives, such as those produced by Isaac Bissell in Birmingham.

This inferior version of a Highland pistol was made by Isaac Bissell of Birmingham, 1740–1780.

This inferior version of a Highland pistol was made by Isaac Bissell of Birmingham, 1740–1780.

Eventually, only wealthy officers could afford such a luxury. By the latter half of the eighteenth century, Highland pistols had become exclusively ceremonial, an expensive accessory for a Scottish officer serving in the British army. The English crackdown on Highland culture following the defeat of the Jacobite rebellion also hastened their decline. By the early nineteenth century, most of the Doune workshops had closed, and their famous gunsmiths had dispersed to other cities. From regional favorite to martial adornment to family heirloom, the Highland pistol had run its course.

Ornate Highland pistol from Christie & Murdoch, 1752

Ornate Highland pistol from Christie & Murdoch, 1752

In the milieu of Deadlands 1876, a Doune pistol would likely appear as a trademark weapon, a valuable antique carried by an eccentric Scotsman as a source of romantic pride. Even today, the Highland pistol still possesses an aura of mystique, a symbol of the enduring fascination with vanishing Highland culture. It is widely claimed that the “shot heard round the world” was fired from a Doune pistol in the possession of Scottish major John Pitcairn, and General George Washington bequeathed his own matched pair to General Lafayette after his death in 1799.

Caplock Pistol

1820s–1850s, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .50 to .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/2, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Common.

Model 1842 percussion pistol, produced in 1849 by Henry Aston

In the decades after the Napoleonic Wars, percussion caplocks became increasingly more popular, finally replacing flintlocks altogether by the early 1840s. Although percussion caps eliminate the messy primer pan and frizzen, caplock pistols are still loaded the same way as flintlocks. A measure of gunpowder is drawn from a powder horn, or dispensed from a pre-measured cartridge of gunpowder, which is contained in a paper or linen packet that is usually bitten open. Once the gunpowder is poured into the muzzle, the shooter inserts the lead ball, which is encased in a lubricated bit of cloth called “wadding.” Pulling the ramrod from its slot beneath the barrel, the shooter tamps the ball home, ensuring firm contact with the propellant charge. The hammer is pulled to half-cock. A percussion cap containing a primary charge of mercury fulminate is placed on a hollow metal “nipple” located beneath the hammer, and the hammer is fully cocked to ready the pistol for firing. Pulling the trigger causes the hammer to strike the percussion cap, which sends its charge into the chamber to explode the gunpowder.

Modern caplock pistol, from Davide Pedersoli

Modern caplock pistol, from Davide Pedersoli

More convenient and reliable than flintlocks, muzzle-loading caplocks were still a victim of their time, and the increasing popularity of revolvers hammered the nails into their collective coffin six bangs at a time. Within two decades, the muzzle-loading pistol was driven to the edge of extinction, and by the time South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter, officers were carrying cap-and-ball revolvers. Percussion caps lasted throughout the Civil War period, but the ascendancy of metal cartridges in the 1870s doomed black powder firearms once and for all.

Underhammer Pistol, “Bootleg,” “Whipsocket”

1826–1860? USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .25 to .52, Range 5/20/40, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d4 to 2d10, Uncommon.

.36 caliber underhammer pistol by Adin Ruggles

.36 caliber underhammer pistol by Adin Ruggles

In the mid-1830s, gunsmiths in New England and New York began producing a type of caplock pistol which placed the hammer underneath the barrel. The story of these characteristically Yankee pistols is both interesting and tragic, and starts in 1825, when the brothers Fordyce and Adin Ruggles established a workshop in Worcester, Massachusetts. A year later the Ruggles received a patent for a percussion pistol fired by an “underhammer,” a hammer mounted beneath the frame that strikes upward at the nipple. This model has two advantages over the standard design. First, because the top of the gun is unencumbered, it may be drawn smoothly and quickly aimed straight down the barrel. Second, the percussion cap explodes downwards, directing its blast away from the shooter’s face and eyes. Unfortunately, the strange design took some getting used to, as Fordyce Ruggles discovered in 1828 when he stopped for a drink at his local tavern. While Fordyce was in conversation with his landlord, a young man sitting next to him surreptitiously fished Ruggles’ pistol out of his coat, only to immediately—and accidentally—fire it point blank into its inventor’s chest. Fordyce Ruggles died fourteen days later from his wounds. Adin relocated the workshop to Stafford, where he continued to produce “underhammer pocket rifles.” Five years later, tragedy struck again. While testing a new pistol, one of Adin’s workers fired it out the back door of the factory. The bullet struck and killed his boss, who had been out taking a casual stroll.

The Stafford factory continued operating under the guidance of Adin’s wife Cynthia, producing many more Ruggles underhammer pistols and spawning a host of imitators; some with, and some without, Cynthia’s blessing. Although their caliber and length varied, these underhammer pistols generally conformed to a characteristic appearance: small and sleek, lacking a trigger-guard, and usually manufactured in matched pairs. Because they could easily be tucked away inside a man’s boot, they acquired the nickname “bootleg pistols,” with some New Englanders referring to them as “whipsocket” pistols.

A matched pair of .31 caliber Case & Willard Underhammer Pistols.

The majority of bootleg pistols are operated in a similar manner. The pistol is loaded from the muzzle, and when the shooter cocks the underhammer, the trigger lowers from the frame. Once a percussion cap is crimped onto the nipple, the pistol is ready to fire. Curved grips are the norm, but some models feature saw-handle stocks, pointed butts, and bulbous handles. Like many handcrafted firearms of this period, engravings, ornamentation, and fancy wood grips are common. For reasons now lost to history, many bootleg pistols manufactured in New England were stamped with a small eagle-and-shield symbol—reflected glory from Springfield Armory?

Hilliard .44 underhammer pistol with detachable shoulder stock, saw-handle grip, and uncharacteristic trigger-guard. Circa 1850.

Hilliard .44 underhammer pistol with detachable shoulder stock, saw-handle grip, and uncharacteristic trigger-guard. Circa 1850.

Characters wishing to equip a bootleg pistol are free to settle on a particular historical model and assign damage according to caliber, with .31 caliber being the most common. Besides the Ruggles family, some common manufacturers of underhammer pistols include Nicanor Kendall, Blunt & Syms, Gibbs Tiffany & Company, and H.J. Hale. Kendall is of particular importance, as his patent was eventually responsible for the famous Robbins & Lawrence firearms company. Details on Kendall’s firearms may be found in the “Kendall Underhammer Rifle” profile in the “Rifles 1. Muzzle-Loaders” section of the Deadlands Armory.

Animal Trap Guns, “Spring Guns”

1820s–present, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber variable, Range 1/2/4, Capacity 1–3, Rate of Fire 1/1+2xCap, DAM variable by caliber, Uncommon. Notes: Some trap guns are loaded with shotgun pellets for DAM 3d6/2d6/1d6. It requires a Notice roll to discover a trap gun, and a Repair roll to disarm it safely. Despite the incredible variety found in the world of firearms, they generally have one thing in common—the muzzle is pointed away from the trigger! Not so with the “trap gun,” an ingenious device consisting of one or more barrels directed at a triggering mechanism. Also known as “spring guns,” these firearms are primarily designed to kill animals. The trigger is set with bait, and when an appropriate amount of pressure is exerted—bang!—dead coyote, wolf, honey badger, etc.

Despite the incredible variety found in the world of firearms, they generally have one thing in common—the muzzle is pointed away from the trigger! Not so with the “trap gun,” an ingenious device consisting of one or more barrels directed at a triggering mechanism. Also known as “spring guns,” these firearms are primarily designed to kill animals. The trigger is set with bait, and when an appropriate amount of pressure is exerted—bang!—dead coyote, wolf, honey badger, etc. The iron arrows on F. Ruethe’s double-barrel trap gun are for setting the bait.

The iron arrows on F. Ruethe’s double-barrel trap gun are for setting the bait.

Of course, humans being what they are, trap guns may be marketed as “burglar alarms,” and some are designed to swivel in the direction of a snagged tripwire. Until England outlawed the practice in 1827, spring guns were deployed by certain questionable landlords to deter, main, or kill poachers. They have also been used to ward off grave robbers, protect armories and magazines, and to surprise dungeon delvers who forget to probe ahead with a ten-foot pole.

The Armory: Muzzle-Loading Pistols, Chapter 2. Specific Profiles

Land Service Pistol, “English Dragoon,” “Heavy Dragoon”

1720s–1790s, UK, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .56 to .66, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 1d10+1d12 to 2d12, Uncommon.

The origins of the “dragoon” pistol may be traced to the dragon, a wheel-lock blunderbuss carried by seventeenth-century French mounted infantry. As the role of mounted soldiers became more specialized, their firearms evolved with them, and by the late eighteenth century most European armies featured “dragoon” units trained in aggressive cavalry tactics. These horsemen were usually armed with a saber, a carbine, and a brace of fearsome pistols. The dragoon kept his pistols in leather holsters located forward the pommel of his saddle, where they could be easily drawn and fired from horseback. Dragoon pistols were known for their long barrels—sometimes up to 14” or more—and their metal buttcaps, usually reinforced by extended “ears” and designed to crush an opponent’s skull.

A replica of a 1704 dragoon pistol from the time of Queen Anne

A replica of a 1704 dragoon pistol from the time of Queen Anne

While the British had a long tradition of high-quality firearms, there was little standardization across their armed forces, a problem that resulted in confusion and disorder as the Empire spread across the globe. In the early eighteenth century, Britain acted to standardize the weapons carried by the King’s soldiers and sailors. The Land Pattern musket, or “Brown Bess,” was used as a template for a new generation of firearms, including the Land Pattern pistol, first produced in the 1720s and partly inspired the baroque designs of Prussian firearms. Known generally as the “English dragoon pistol,” the gun is nearly 20” long, weighs four pounds, and sports a 12” barrel. Featuring a brass trigger-guard and buttcap with elongated ears, the pistol’s most distinctive feature is the raised wood around the lockplate and the Brown Bess-style “swell” to the forestock. The pistol was issued in two bore sizes. Although the actual measurements varied from maker to maker, “pistol” bore was nominally .56 caliber and “carbine” bore was .66 caliber. After Colonel Elliot’s shorter version was introduced in 1759, the original pistol became known as the “heavy dragoon.” Produced for many decades in numerous variations, the English dragoon pistol was used from the Battle of Culloden Moor to the American Revolution, where it was carried by Loyalist and Patriot alike. It was also a popular pirate weapon!

Sea Service Pistol

1716–1815, UK, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .54 to .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Uncommon.

British Sea Service Pistol, 12” barrel, Tower Armory 1805

British Sea Service Pistol, 12” barrel, Tower Armory 1805

Until the early part of the eighteenth century, British sailors and Naval officers simply used whatever pistols they acquired on land, usually dragoon pistols designed to be fired once and then used as a club. The same drive toward standardization that brought about the Land Pattern musket also impacted the Royal Navy, and in 1716 the first “Sea Service” pistols were issued. Similar to the English dragoon pistol, the original Sea Service pistol sports a 12” barrel, but is fitted with a more conventional brass buttcap and lacks the distinctive stock swell. The hammer is reinforced with a “ring-neck” element, and the left side is fitted with a steel belt hook. In the 1790s, the East India Company shortened the barrel to 9”, making the pistol a more manageable length for shipboard combat. This barrel length was adopted for subsequent versions of the pistol, which carried British sailors all the way through the Napoleonic Wars.

Pistolet modèle 1733

1731–1763, France, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .64 to .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 1d10+1d12 to 2d12, Uncommon.

Mle. 1733 pistolet, officer variant from 1740, 14” barrel, .65 caliber

Mle. 1733 pistolet, officer variant from 1740, 14” barrel, .65 caliber

In 1731, the French attempted to standardize their military pistol by adopting a general pattern across their entire armed forces. After a short-lived Mle. 1731 prototype, the highly-successful Mle. 1733 was introduced. The standard version has brass furnishings and a 12-¼” long barrel with a .67 bore. The dragoon-style buttcap features extended ears, and the hammer sports a jauntily curled cocking spur. Produced for over three decades, many variations exist, including a version with steel furnishings, and officer’s model adorned with fancy embellishments.

The left side of the above pistol, with engraving

The left side of the above pistol, with engraving

Like the popular “Charleville” musket, the Mle. 1733 pistol followed French interests around the globe, and saw frequent action beyond continental Europe, from the Jacobite uprising in Scotland to the French and Indian War in America. More than a few aging Mle. 1733 pistols even showed up for the American Revolution.

Pattern 1759 Pistol, “Light Dragoon Pistol,” “Elliot Pattern”

1760s–1820s, France, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .62, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Uncommon.

In 1759, Colonel George Augustus Elliot was given the task of raising the first regiment of British “Light” Dragoons. Unsatisfied with the standard Land Pattern pistol, Colonel Elliot decided to equip his men with his own version of the dragoon pistol. Curtailing its unwieldy twelve-inch barrel to nine inches and shortening the grip, Elliot made the pistol more manageable. He reduced the amount brass needed for the furniture, and standardized the bore to accept the same .66 caliber ammunition used by his men’s carbines.

Pattern 1799 Elliot Light Dragoon Pistol. Note the ring-necked hammer.

Pattern 1799 Elliot Light Dragoon Pistol. Note the ring-necked hammer.

Elliot’s modified pistol was a resounding success, and with a few additional modifications over the years, it served the British military for nearly half a century. Because it weighs less than the standard Land Pattern pistol, Elliot’s pattern became known as the “light dragoon pistol,” with the former becoming the “heavy dragoon pistol.” The pistol saw extensive use in the American Revolution, whether in the hands of British soldiers, or issued to Loyalists defending their interests against the Patriot rebellion.

Pistolet modèle 1763/66

1763–1801, France, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .64 to .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 1d10+1d12 to 2d12, Uncommon.

The Seven Year’s War inflicted a humiliating defeat on France at the hands of their traditional foe, the English. In response to this loss, Foreign Minister Étienne François, the Duke of Choiseul, launched a campaign to modernize the French Army and Navy. Part of Choiseul’s campaign involved updating French armaments, and the venerable Mle. 1733 pistol was replaced by the Mle. 1763, which more closely resembled the contemporary Charleville musket. In 1766, the barrel was shortened, resulting in a more handy pistol sometimes referred to as the Mle. 1763/66. The Mle. 1763/66 features a 9” barrel with a .71 bore, and is designed to accept the same cartridges used by the Charleville musket. Like most French weapons, many of these pistols found their way to the United States, including a shipment procured by Benjamin Franklin in 1777.

Pistolet modèle 1777, “Charleville”

1777–1840, France, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Uncommon.

Patterned on the firelock used by the modèle 1777 “Charleville” musket, this French pistol sports a 7-½” long steel barrel. The left side features as steel belt hook, with all the other furnishings made from brass, including the lockplate, primer pan, trigger-guard, and buttcap. The pistol lacks a forestock, the steel ramrod fitting into a slot located at the lower right side of the frame. Brought to the United States during the American Revolution, the Mle. 1777 was borrowed as the template for the first American pistol, the U.S. Model 1799.

Although admired by the American patriots, the Mle. 1777 was not as beloved by Revolutionary troops back home, who preferred the earlier Mle. 1863/66. After the French arms industry fell to Revolutionary forces, many French armories continued to manufacture the earlier model until the turn of the century. As a result, Napoleon’s officers and dragoons carried a mix of pistols on their campaigns across Europe.

New Land Pattern Cavalry Pistol

1796s–1815?, UK, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .71 bore/.69 balls, Range 3/10/25, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Uncommon.

First developed by the East India Company for their private army, the New Land Pattern Cavalry pistol was an attempt to create a light dragoon pistol for all British mounted and artillery units. Easily distinguished from Elliot’s model by its flat buttplate and lanyard ring, the New Land Pattern pistol was the main British handgun of the Napoleonic era. As with many firearms of this period, variations exist, with barrels ranging from seven to nine inches and bores from .62 to .69 caliber. The pistols arming the units of the East India Company sport a prancing lion stamp on the lockplate. The New Land Pattern was not considered a very accurate pistol, and if a cavalry trooper was not careful, he could dangerously overcharge its barrel by accidentally using a carbine cartridge!

U.S. Model 1799 Pistol, “North-Cheney”

1799–1802, USA, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .69, Range 3/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Very rare.

With England and Revolutionary France growing increasingly hostile toward American interests, the fledgling U.S. government began preparations for potential hostilities. Recognizing the need for a native firearm industry, in 1794 Congress authorized funds for the construction of two federal armories—the first at Springfield Arsenal, and a the second at Harpers Ferry in Virginia. That same year, the government issued its first procurement order for American-made infantry muskets and pistols. This historic call to arms sparked the American firearms industry by attracting two likeminded men to the business of gunmaking—Eli Whitney and Simeon North. Both born in 1865, they would become pioneers of the mass-production techniques that came to define American industrialism. The story of Eli Whitney may be found in the Deadlands Armory under the profile of the “U.S. Model 1795 musket.” The story of Simeon North is less well known, and begins with the U.S. Model 1799 pistol, the first official handgun adopted by the United States of America.

Simeon North

A cigar-chomping, teetotaling, sixth-generation New Englander who attempted to enlist in the Continental Army when he was just sixteen, Simeon North was an industrious young blacksmith with knack for invention and a streak of Yankee can-do spirit. In 1795, North purchased a sawmill adjacent his family farm and converted it into a workshop dedicated to producing scythes. In 1799, North accepted a contract from the U.S. government to make 500 “horse pistols,” with a second order for 1500 following shortly thereafter. With help from his brother-in-law, the clockmaker Elisha Cheney, the thirty-four-year-old blacksmith completed the full order by 1802. It was, as they say, the beginnings of a beautiful relationship. As described later in the Armory, Simeon North would continue working with the government until his death in 1852.

Like the U.S. Model 1795 musket, the U.S. Model 1799 pistol is little more than an American copy of the French modèle 1777 “Charleville” pattern. North’s pistol is distinguishable by its 8-½” barrel, which is an inch longer than the Charleville. It is believed that Captain Meriwether Lewis purchased a pair of these pistols in Philadelphia just prior to the Lewis & Clark expedition. A well-made pistol, even in 1876 it was considered a valuable antique, worth significantly more than its French predecessor!

U.S. Model 1805 Pistol, “Harpers Ferry Pistol”

1806–1808, USA, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .54, Range 5/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Uncommon.

The first military handgun manufactured at a Federal armory, over four thousand Model 1805 flintlocks were produced at the newly-established Harpers Ferry Armory between 1805–1808. Intended primarily for officers, the pistols were produced in matched pairs and issued with identical serial numbers. Loosely modeled on the English dragoon pistol, the Model 1805 has a 10-1/16” barrel supported by a stock of black walnut. The pistol features a sturdy, ring-necked hammer, a brass-tipped hickory ramrod, and an eagle stamp on the steel lockplate. The furnishings are all brass, including a brass buttcap with elongated ears. Curiously, a few of these pistols were produced with rifled barrels.

Known as the “Harpers Ferry pistol,” the Model 1805 was quite popular, handsome and sturdy, and saw use during the War of 1812. Considered by many to be the iconic American flintlock, in 1923 the United States Army Military Police Corp adopted a pair of crossed Harpers Ferry pistols are their heraldic insignia.

Simeon North Contract Pistols

1808–1829, USA, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .54 to .69, Range 5/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, Common.

Simeon North U.S. Navy Model 1813 pistol. Note the brass pan and the double-strap barrel band.

Simeon North U.S. Navy Model 1813 pistol. Note the brass pan and the double-strap barrel band.

After completing the contract for two thousand Model 1799 pistols, Connecticut gunsmith Simeon North returned to manufacturing farming implements. Growing bored with the work, North decided to beat some ploughshares into swords, and applied for a contract to produce 2000 “boarding pistols” for the U.S. Navy. He was awarded the contract, putting into production the U.S. Model 1808 Navy pistol. Unlike North’s Charleville copy, his new pistol featured a wooden stock, and was more closely aligned with the sturdy French models of the previous Mle. 1763/66 generation. As he tooled up for this large order, North began experimenting with the idea of interchangeable parts, and initiated a cordial correspondence with the government about the various improvements he could make, both in terms of design and methods of mass production. Additional contracts followed, and over the next few years Simeon North’s Berlin factory became a leader in modern manufacturing techniques, inventing new milling machines that enabled the efficient use of interchangeable parts.

Ever the patriot, Simeon North was infuriated by England’s rash decision to illegally impress American sailors, and joined the growing war fever that marked the end of the new century’s first decade. He was elected Lieutenant Colonel of the Sixth Connecticut Regiment in 1811. Fortunately for a government that prized North’s mechanical ingenuity more than his military leadership, he resigned his commission two years later and returned home. Nevertheless, his workers, neighbors, and family referred to him as Colonel North from that point onwards. His business booming, Colonel North established a second factory in Middletown, turning control of the Berlin factory over to his son Reuben North in 1814.

The twenty-year run of North contract pistols passed through several iterations. The first model was the .64 caliber 10” barrel Model 1808 Navy pistol, which saw extensive use in the War of 1812. The Model 1811 reduced the barrel length but upped the caliber to .69, and the subsequent Model 1813 Army and Navy pistols added a distinctive “double strap” barrel band. The Model 1816 reduced the caliber to .54, with the Model 1819 adopting a canted barrel band that carried over to the slightly-smaller Model 1826.

After producing over 50,000 pistols for the United States government, Simeon North struck up a relationship with fellow interchangeable-parts pioneer John Hall of Harpers Ferry Armory. Leaving the production of pistols to his successors, Colonel North spent the rest of his life improving and manufacturing Hall’s breech-loaded rifles at his Middletown factory. (See the “Rifles” section of the Deadlands Armory for more details.)

Model 1836 Flintlock Pistol

1836–1844, USA, muzzle-loading flintlock. Caliber .54, Range 5/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Uncommon.

Produced in Connecticut by Asa Waters in Millbury and Robert Johnson in Middletown, this mass-produced gun was the final flintlock pistol produced for military use in the United States, and is generally considered to among the most handsome and reliable. An improved version of North’s Model 1826, the Model 1836 sports an 8-½” barrel; features a case-hardened lockplate, hammer, and frizzen; and has a brass primer pan. It was the primary handgun of the Mexican-American War, and many Model 1836 pistols were later converted to caplocks, used all the way to the Civil War.

Ethan Allen Percussion Pistols

1836–1871, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .28 to .45, Range 5/15/30, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d4 to 2d8, Uncommon. Notes: Given the many variations of this firearm, characters wishing to equip an Allen single-shot pistol should specify the model and caliber. These stats may also be used for Allen’s many competitors.

First Model Allen Pocket Rifle, with rare 10” barrel with sights.

One of the most storied names in American firearms is Ethan Allen. Of no relation to the Revolutionary War hero of the same name, Ethan Allen of Massachusetts was manufacturing cutlery in North Grafton when he was contracted to produce a cane gun by one Dr. Roger Lambert. Inspired by the project, Allen began producing underhammer “pocket rifles,” earning his first patent in 1837 for a “tube hammer” percussion pistol fired using a curved, tubular side-hammer. Partnering with his brother-in-law Charles Thurber, the inventor of the first typewriter, “Ethan & Thurber” began producing a wide range of firearms. In 1854, the firm became “Allen & Company” when they accepted another brother-in-law, Thomas Wheelock, as a third partner; and then “Allen & Wheelock” after Thurber’s retirement in 1856. After Wheelock died in 1864, Allen continued producing firearms under his own name until his death in 1871, after which his company was reorganized by his sons-in-law as “Forehand & Wadsworth.”

Allen & Thurber Sidehammer Pistol, .41 caliber, missing its ramrod. Circa early 1850s.

An early proponent of interchangeable parts, Ethan Allen produced thousands of guns, ranging from his famous pepperbox pistols to the Drop Breech Rimfire Rifle featured elsewhere in the Deadlands Armory. His guns were prized for their high quality, and often featured elaborate engravings, furnishings of German silver, and handsome grips of ivory, pearl, or rosewood. Although Allen is best known for his pepperbox pistols, he created numerous breech-loading pistols in a wide variety of styles: underhammers, tube-hammers, bar-hammers, and side-hammers; ring triggers, standard triggers, and spur triggers; single, double, and even triple-barreled. During this time, Allen’s work was frequently copied by others, with Bruce & Davis, Spaulding & Fisher, and Blunt & Syms being his most prolific competitors.

U.S. Navy Elgin Cutlass Pistol

1838, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .54, Range 3/10/20, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM Pistol 2d12, Blade 1d4+STR, Very rare. Note: If the blade is used prior to firing the pistol, each round of mêlée combat contributes 5% to a cumulative chance that the pistol will misfire—the ball becomes unseated, the percussion cap drops off, etc.

One of the best-known examples of a “sword pistol,” this nasty piece of work was produced under government contract by C.B. Allen of Springfield, Massachusetts. It consists of little more than George Elgin’s 11” Bowie knife fused to the frame of a .54 caliber flintlock. Each Elgin pistol was issued with a leather sheath tipped in German silver.

Curiously, the Elgin Pistol was the first percussion cap pistol made for U.S. armed forces.The Navy purchased 150 Elgin pistols to accompany Charles Wilkes’ United States Exploring Mission of 1838–1842. A massive expedition to survey the Pacific Ocean, the project was one of the greatest scientific endeavors of the time, an extension of American colonialism that helped open up the Pacific for development. Circumnavigating the globe, the Wilkes expedition charted the western coastlines of North and South America, reached all the way to Antarctica, and explored the Pacific Islands essential to the American whaling industry. The scientific knowledge acquired placed the United States at the forefront of oceanography, and the samples gathered helped fill the halls of the new Smithsonian Institution.

The mission was not without its share of controversy. The tyrannical “Commodore” Wilkes lost two ships, humiliated his officers, brutalized his sailors, and presided over a massacre of Fiji natives. Court-martialed upon returning, Wilkes eventually covered himself with additional infamy as the captain of the U.S.S. San Jacinto, the American ship that triggered the Trent affair in the early days of the Civil War.

This .40 caliber version of the Elgin pistol is half the normal size, has an ivory grip, and “fire blue” hammer.

This .40 caliber version of the Elgin pistol is half the normal size, has an ivory grip, and “fire blue” hammer.

Model 1842 Percussion Pistol

1845–1852, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .54, Range 5/20/40, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Common.

Originally manufactured in Middletown, Connecticut by former Simeon North employee Henry Aston, the Model 1842 was the first percussion pistol mass-produced for the U.S. military. Essentially an update of the Model 1836, the new percussion pistol continued the smooth lines of the North models and shifted to all-brass furnishings, including the front sight blade.

The Palmetto Dragoons

While the majority of Model 1842 pistols were manufactured in New England by Henry Aston and Ira N. Johnson, over a thousand were produced in South Carolina under somewhat unusual circumstances. As talk of secession became more prevalent in the late 1840s, the government of South Carolina became understandably alarmed that both Federal armories were located somewhat north of Columbia. The state decided to establish its own armory, a factory capable of producing swords and firearms for South Carolina militias. In 1851, they awarded the contract to an entrepreneurial jeweler and former dragoon named William Glaze. With the company founded by Asa Waters closing its doors, Glaze was joined by Benjamin Flagg, the former superintendent of Waters’ factory in Millbury, who brought along some of his equipment. Together they founded the Palmetto Armory in Columbia, South Carolina, where they accepted contracts to convert flintlocks to caplocks, produce cavalry swords and bayonets, and manufacture rifles and pistols based on the Model 1842 pattern.

Still tooling up their factory, Glaze and Flagg purchased a surplus of over-run and condemned Model 1842 parts from Aston and Johnson. Some of these were used to convert existing flintlocks, while others were assembled into “new” Model 1842 muskets and pistols. Although not all of these firearms passed inspection, the Palmetto Armory was successful in delivering the promised guns, but additional contracts were not forthcoming. Seeking to remain solvent during the 1850s, the armory was reorganized as the Palmetto Iron Works, adding steam engines and cotton gins to its expanding repertoire. The secession of South Carolina in 1861 reinvigorated the armory, which suddenly found itself the largest firearms producer south of Harpers Ferry, and continued to turn out Southern “copies” of Northern patterns all throughout the War. The Palmetto version of the Model 1842 “Dragoon” pistol is identical to the northern pistols, but features the distinctive palm-tree stamp and “PALMETTO S.C.” markings. Needless to say, it saw some use in Confederate hands early in the War.

Palmetto Armory Model 1842. Note the distinctive stamp.

Palmetto Armory Model 1842. Note the distinctive stamp.

Experimental Models

The Model 1842 is also notable for having served as the basis for various automatic priming systems. Produced in very low numbers, these experimental variants are exceptionally rare, and are detailed below.

Maynard Patent Self-Priming Single Shot Model 1842 Type Pistol

1845, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .54, Range 5/20/40, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Very rare. Note: On a Natural 1, the priming pellet fails to detonate.

In 1845-1846, Springfield Armory produced a handful of Model 1842 pistols equipped with the Maynard priming tape system. There are two main variants of this pistol, both accepting a roll of primer tape inside the characteristic “hump-shaped” lockplate.

Rupertus Automatic Priming System Conversion of Model 1842 Pistol

1859–1860, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .54, Range 5/20/40, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Very rare.

The creation of Jacob Rupertus of Pennsylvania, these Model 1842 pistols are equipped with Rupertus’ automatic priming system. Replacing the standard nipple with a rotating drum, the Rupertus conversion stores spherical priming pellets in a tubular magazine located along the top of the lockplate. When the hammer is cocked, the drum rotates to the rear to receive a pellet; releasing the trigger snaps the drum into place, aligning the priming pellet with the falling hammer. Only a hundred or so were produced.

Model 1855 Percussion Pistol-Carbine

1855–1857, USA, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .58, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d12, Rare. Note: On a Natural 1, the priming pellet fails to detonate.

One of the more unusual firearms to be produced at Springfield Armory, the Model 1855 Pistol-Carbine sports a 12” long rifled barrel, a 25-pellet Maynard priming tape system, and a detachable buttstock. It’s chambered for the same .58 caliber Minié ball used by the Model 1855 musket. The user may forgo the Maynard tape and fit the nipple with a standard percussion cap. With slightly over 4000 placed into production, the gun was designed to be carried as a pistol on horseback and used as a carbine on foot, and was issued to the 1st and 2nd Cavalry for use in the West. A few variant models were also produced at Harpers Ferry, but these lacked the Maynard tape system.

The Model 1855 Pistol-Carbine was an unpopular firearm. Bulky as a pistol, inaccurate as a carbine, it was not well-made, and repeated use tends to jar loose the detachable stock and split the wooden grip. It was also the victim of unfortunate timing. Produced during the twilight years of single-shot handguns, the popularity of the Colt revolver doomed this strange hybrid shortly before the Civil War. Springfield Armory would not mass-produce another pistol until Browning’s 1911 Automatic.

Yerty Burglar Alarm and Animal Trap Gun, “Horseshoe Gun”

1866–present, muzzle-loading caplock. Caliber .32, Range 1/2/4, Capacity 2, Rate of Fire 2/5*, DAM 3d6, Uncommon. Note: It requires a Notice roll to discover the trap gun, and a Repair roll to disarm it safely. The horseshoe gun is not designed to be used as a handgun, but may be fired manually at a –2 penalty on the Shooting roll. Patented in 1866 by Henry Yerty of Sidney, Ohio, this trap gun looks like something M.C. Escher might have designed when he was pissed at his neighbors. Intended to be mounted on a post, the vertical brass cone in the center is hollow, and allows for full 360° rotation. The slender rod projecting between the barrels is drilled with a hole near the end; a cord or wire passes through this hole to set the trap. When an animal—or intruder!—trips the wire, the horseshoe gun swivels in the appropriate direction, and the tension drops the steel hammers. The unfortunate coyote, trespasser, or grave robber is welcomed by a pair of .32 caliber lead balls.

Patented in 1866 by Henry Yerty of Sidney, Ohio, this trap gun looks like something M.C. Escher might have designed when he was pissed at his neighbors. Intended to be mounted on a post, the vertical brass cone in the center is hollow, and allows for full 360° rotation. The slender rod projecting between the barrels is drilled with a hole near the end; a cord or wire passes through this hole to set the trap. When an animal—or intruder!—trips the wire, the horseshoe gun swivels in the appropriate direction, and the tension drops the steel hammers. The unfortunate coyote, trespasser, or grave robber is welcomed by a pair of .32 caliber lead balls.

Interestingly, Yerty’s next invention was an improved milk-house: “By the use of my invention milk can always be preserved in any season and in all kinds of weather, while butter can be always kept from becoming rancid and soft, and meat be prevented from becoming fly-blown.” Woe to those foolish burglars who tried to steal some of Yerty’s hard butter!

<< Rules | Innovations | Breech | Derringer | Pepperbox | Revolver >>

Sources & Notes

Books

To create this resource, I leaned heavily on Norm Flayderman’s Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms. Featuring photographs and detailed descriptions of thousands of antique firearms, this is an essential resource for any historical gaming campaign, and Flayderman’s Guide introduced me to several of the more bizarre weapons described in the Deadlands Armory. I also recommend Dennis Adler’s Guns of the American West and David Miller’s Illustrated Book of Guns. Both feature historical notes and full-color illustrations of the West’s most iconic firearms, many of which are museum pieces photographed especially for these books.

Internet

Of course, the Internet was crucial for my research. The Web is filled with antique firearm collectors, and much of the information in the Armory was gathered from gun-ownership forums, antique auction sites, and the homepages of Civil War reenactors. Anyone interested in the historical firearms described in the Armory can find a wealth of additional information online, including videos of many of these guns being loaded and fired—sometimes by authentically-costumed reenactors! But without a doubt, the most useful resource on obscure firearms is Ian McCollum’s Forgotten Weapons. Perpetually cheerful and possessing a dry sense of humor, McCollum works in conjunction with auction houses to produce short videos spotlighting authentic antique firearms. McCollum explains their history, carefully reveals their inner workings, and sometimes takes them to the firing range. I also relied on Wikipedia, Antique Arms, and the Firearms History, Technology & Development blog.

Image Credits

Many of the photographs of firearms used in the Armory have been “borrowed” from online sources. Because most owners of vintage firearms are good-natured folk with a passion for promoting their hobby, I have no doubt they’ll be happy to see their photographs used to promote a wider understanding of antique weaponry. Having said that, if anyone is offended that I’m using an image without proper authorization, please contact me and I’ll remove it immediately. Many photographs depict modern reproductions, usually manufactured by Uberti, Pietta, Pedersoli, Cimarron, Taylor’s, or Dixie Gun Works. I favor these photographs because they make the gun look contemporary, something a Deadlands character might purchase in a gun store or pry from the cold, dead fingers of his enemy. When I could not find a shiny new replica, I usually turned to vintage gun auctions. The four best resources for detailed images of antique firearms are the Rock Island Auction Company, James D. Julia Auctioneers, College Hill Arsenal, and the Collectors Archives from Collectors Firearms, Inc. Thank you!

Specific Online Sources

The following sites were invaluable in creating this resource: FHT&D’s entry on the Highland Pistol, Nicholas Chandler and Terry Berry’s informative Ruggles Patented Underhammer of 1826, the NRA Museum entry on Nicanor Kendall, College Hill Arsenal’s entry on the Mle. 1733 pistolet and the Elliot “Light Dragon” pistol, the entry on the Mle. 1763/66 at Military Heritage, Jack Allen Meyer’s William Glaze and the Palmetto Armory, Phil Spangenberger’s A Pistol for Dragoons from True West magazine, and the monograph Simeon North: America’s First Official Pistol Maker of the United States, by S.N.D. North & Ralph H. North, Rumford Press 1913.

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 2018 June 28

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

PDF Version: Deadlands Armory – Handguns 1. Muzzle-Loading Pistols