Pynchon Music: Steven Ricks

- At January 02, 2022

- By Spermatikos Logos

- In Pynchon, The Modern Word

0

0

Steven Ricks (b. 1969)

Born in 1969, American composer Steven Ricks grew up in Arizona, where he learned to play trombone. He earned his bachelor of music at Brigham Young University, his masters in composition from from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and a Ph.D. in composition from the University of Utah. In 1999 Ricks received a Graduate Research Fellowship that took him to King’s College London, where he spent a year studying under Sir Harrison Birtwistle. Ricks currently teaches music theory and composition at Brigham Young University. He directed the BYU Electronic Music Studio from 2001–2021.

Pynchon Connection

Several of Steven Ricks’ pieces have been influenced by literature, from haiku poems to the Bardo Thödol, or Tibetan Book of the Dead. His album of experimental electronic pieces, Strange Enthusiasm, references Kurt Vonnegut’s Thanasphere, while Ten Short Musical Thoughts has its origins in Vonnegut’s Kilgore Trout. Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow has inspired two major electroacoustic pieces, American Dreamscape and Beyond the Zero, both featured on the 2008 Bridge CD, Mild Violence. Ricks contributed an excerpt of the latter work, “A Glimpse Beyond the Zero,” to 60×60, an avant-garde anthology of 60-second pieces released by Vox Novus in 2007.

In February 2022, Allen Ruch of the Modern Word interviewed Steven Ricks about his Pynchon-related pieces, the influence of literature on his work, and his development as an electroacoustic composer.

Review: American Dreamscape and Beyond the Zero

Mild Violence collects six pieces Steven Ricks composed between 2000 and 2006. Most of these works share a common theme: the sudden transition from the mortal plane to some form of afterlife. This may be metaphorical, such as Slothrop’s voyage to the America underworld in American Dreamscape; or it may be literal, such as Mild Violence itself, which alludes to the lynching of Mormon founder Joseph Smith in 1844. As befitting such themes, the music is animated by dramatic gestures, sharp angularities, and moments of ethereal beauty.

Ricks is an electroacoustic composer, and four of the works on Mild Violence feature electronics. However, those accustomed to the tweedles and bleeps of the Stockhausen school may be in for a surprise—Ricks has a thoroughly modern appreciation of electronics, informed by rock music just as much as the mid-century avant-garde. The electronics on Mild Violence are never intrusive or gimmicky. They are essential elements, as fully-realized and substantive as the flutes, violins, and saxophones they often mirror and distort. To quote Jeremy Grimshaw’s insightful liner notes, “in the electroacoustic works, there’s a hint of the body/spirit duality, the pairing of the phenomenal and the nouminal, manifested in the way the electronic sounds, coming from unseen sources, swirl around the live performers like ghosts.”

While the entire album is exceptional—this is modern music at its best, played with conviction and recorded with precision and fidelity—this review focuses on the two Pynchon-inspired pieces, American Dreamscape (track 3) and Beyond the Zero (track 5).

Scored for an alto saxophone, piano, bass, percussion, and electronics, American Dreamscape is dedicated to avant-garde saxophone player John Sampen, who premiered the piece in 2005 and who plays on this recording. American Dreamscape is inspired by the famous scene in Gravity’s Rainbow where Slothrop hallucinates plunging into the toilet of the Roseland Ballroom, his orphic quest to retrieve his lost mouth-harp accompanied by the sound of Charlie Parker playing “Cherokee.” Possibly the most virtuosic passage of scatological literature written since Ulysses, the sequence uses Beat surrealism to illuminate the dark underbelly of American racial history, from bourgeois anxieties about Malcolm X to the Native American genocide.

The beginning of American Dreamscape is startling but effective. Subdued crowd noises and jazz piano are scattered as the piece arrives backwards through time: the tape rewinds faster and faster, accelerating to a sudden crescendo à la the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” Instead of resolving into a jaunty melody or sustained E-major, we’re brought directly to a skittery piano, like nervous fingers trying to find something lost in the dark. The saxophone enters with a strange, muted peeping, and the “dreamscape” begins to take form. For the most part, each instrument is content to play in isolation. The sax warbles through a range of modernist poses, at times even sounding like a bassoon; while the drums sporadically explode into jazzy flourishes; stray snippets from some other stage. The electronics are restrained, an occasional touch of echoing, processing, or gating to clip discrete sounds. Meanwhile the piano and bass continue their restless searching. Occasionally the four instruments unite for a single gesture; but these are sudden conjunctions, not lasting unions. While Ricks has cited Parker’s improvisations on “Cherokee” as an influence, there’s little direct quotation, just echoes and deconstructions.

Four minutes into the piece, American Dreamscape takes a radical turn. Everything slows down, becomes more subterranean; given Ricks’ inspiration, it’s safe to assume Slothrop has passed through the “stone-white cervix” and has found himself in the primordial sewers of the American subconscious. And while American Dreamscape can hardly be read as programmatic, the “light down here is dark gray and rather faint.” Glassy notes bowed from a vibraphone are plowed aside by gliding peals of bass, electronically plunged deep into subwoofer territory. The saxophone is more tentative now, a wavering, brassy torch leading into the gloom. As the submarine bass sinks from hearing, the alto finds itself abandoned and alone. It flares to life, a defiant solo flickering through a maze of sharps and flats, echoes returning from some invisible, electronic distance. Again, Pynchon’s description comes to mind: “icky and sticky, cryptic and glyptic, these shapes loom and pass smoothly as he continues on down the long cloudy waste line, the sounds of ‘Cherokee’ still pulsing very dimly above, playing him to the sea.”

Eventually the drums reappear, a dramatic herald of the coming apocalypse—a surge of electronic distortion that crackles through the piece like wind from a smoldering fire. Or perhaps it’s the “jam-packed wavefront” that carries Slothrop to the ruinous wasteland? As the electronic deluge recedes, there’s an eerie sense that something has been exposed, some stark emptiness populated by skeletal ruins. Finally exhausted, the alto mutters a mournful threnody above a quivering vibraphone. The end comes quietly, key by key, as the piano climbs into its highest register and disappears: “something else has been terribly at this country, something poor soggy Slothrop cannot see or hear…”

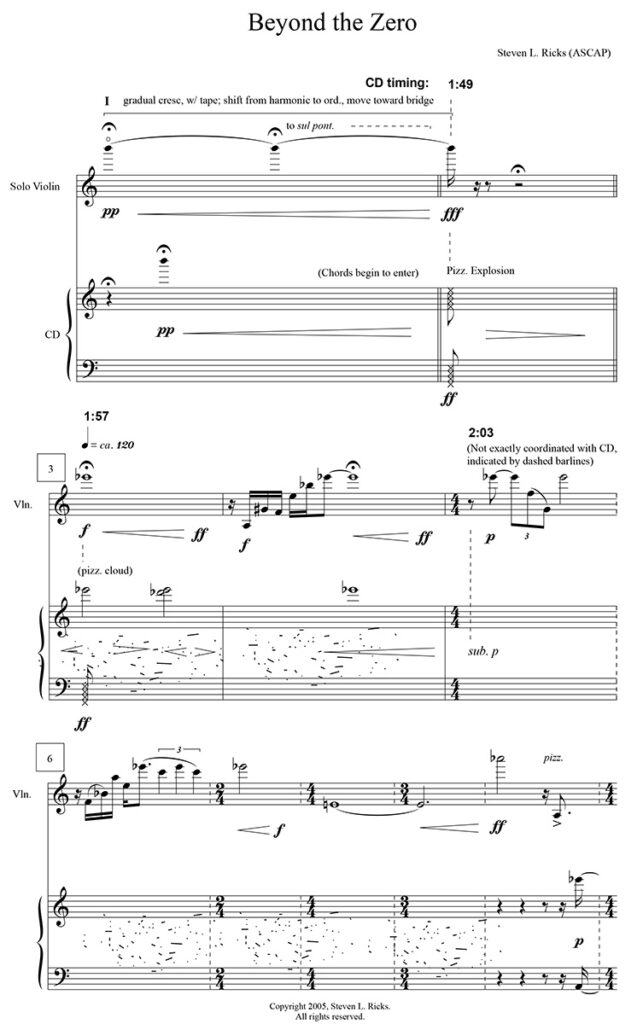

The second Pynchon-inspired piece is Beyond the Zero, for violin and electronics. In concert, the piece is staged with the violinist playing to a recording of the electronics. This recording contains a battery of effects, including samples of violin originally played by Danish violinist Bodil Rørbech. On the CD, the “live” violinist is Curtis Macomber, who first premiered the piece in 2005.

A musical meditation on the Pavlovian allusion that begins Gravity’s Rainbow, Beyond the Zero uses the novel’s V-2 rocket as a metaphor for the abrupt transitions between different states of being. Expressing his fascination with the supersonic rocket’s ability to arrive before the sound of its coming, Ricks has stated that the so-called “Zero” represents “a threshold that one could push past; a sort of metaphor for the journey of the soul from a preexistence, to mortal life, to an afterlife.”

Beyond the Zero begins with a literal—but powerful—musical translation of the novel’s famous opening sentence, “A screaming comes across the sky.” Here that’s a high-B harmonic that hangs in the air for 108 threatening seconds, growing increasingly louder and more electronically distorted. The crash arrives with an explosion of pizzicato, the sound multiplied hundreds of times, a whirling cloud of reverberating echoes. The effect is electrifying and somewhat surreal—or perhaps Cubist. Evoking Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, the electronics multiply the violin through the dimensions of time and space, transforming the instrument into some segmented creature: a twisting centipede of wooden bows and plucked strings. As the soloist takes center stage, he’s forced into a tense duet with this electronic doppelgänger, and their relationship is never certain: sometimes cooperative, sometimes antagonistic. According to Ricks, if the “screaming” represents birth into this world, the electronics are “symbolic of the turbulent experience of life on this planet.”

As the piece evolves—or to follow Ricks’ metaphor, matures—the electronics intensify. No longer relying on acoustic violin for samples, Ricks brings a Roland JV-1080 into play, unleashing a percussive hailstorm of cimbalom effects. While the replicated violin was at least quasi-organic, this onslaught of electronic beats feels punishingly indifferent, trading the continuity of Cubism for the stark impact of Brutalism. Despite the chaos, the soloist heroically carries on. A crescendo is reached as the violin is overwhelmed by a wave of distorted electronics. As with many of the pieces on Mild Violence, this sense of “going under” leads to transformation. Similar to American Dreamscape, the apocalyptic surge is followed by the revelation of a new space, quiet and expansive. Now free from the hurly-burly, the violin gives voice to a beautiful but enigmatic solo that evokes the mystery of Berg and Britten. Suspended above a diminishing glimmer of electronics, the violin floats higher in pitch until vanishing in ultraviolet silence.

Notes

There is something of a knowing wink accompanying the title of this collection, “Mild Violence.” On the one hand, it’s a clever pop culture reference: a curious phrase borrowed, the composer says, from the Entertainment Software Rating Board notice on a video game, It’s a clinical label, meant to alert the user to merely cartoonish malice, acted out in harmless, imaginary spheres, Anthropomorphic animals flattening each other’s bodies with grand pianos, then, after the spinning stars and cuckoobird sound effects have subsided, springing back to life. In fact, the rich timbral extremities and bustling rhythmic angularity that much of the music on this recording offers in such abundance could well serve as a soundtrack to such imagery. On the other hand, this arena of the absurd, in which antagonists zigzag willy-nilly across the liminal boundaries of mortality, thinly veils some of the composer’s more cosmic ruminations: divine Creation, the martyrdom of saints, visions of the afterlife. In the electroacoustic works, there’s a hint of the body/spirit duality, the pairing of the phenomenal and the nouminal, manifested in the way the electronic sounds, coming from unseen sources, swirl around die live performers like ghosts—occasionally even possessing them. And although there’s no religious dogma here, as I listen to these works it’s hard for me, as co-religionist with the composer, to not hear the Mormon notion that “all spirit is matter, but more refined or pure.” Or to put it another way, Ricks likes to present sounds as if they exist on a spectrum of perception that fades into the mists on either end, rather than stopping abruptly at the edge of the aural. The music imagines the permeable boundary between life and death, this world and the other, and, like the reckless characters in a videogame, slaloms across that boundary. Violence, to be sure, but violence experienced voyeuristically through music: thus, at least as a matter of consumer liability, mild.

Coming off of the tapered end of Mild Violence, the beginning of the subsequent work, American Dreamscape, falls into a chance but nonetheless pleasing symmetry. It clearly suggests uncontrolled kinetic motion—a runaway train, or perhaps a runaway tape reel, spinning faster and faster until it melts onto the rape head. This is the first of the piece’s numerous hallucinations, swirling as it does through a delirium of musical scenes. We can call this one programmatic, in a sense, only because its literary inspiration, a passage from Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow, is so fragmentary, surreal, nonlinear—and explicitly musical. The scene in question evokes utter disorientation: a character by the name of Slothrop, drugged in a hospital ward, imagines himself in the bathroom of the Roseland Ballroom, “Cherokee” playing downstairs on the dance floor. Slothrop descends. Orpheus-like, through the toilet down into the sewer to retrieve the mouth harp he has dropped. At that very moment somewhere else in Manhattan, Charlie Parker, in a symmetrically Orphic fashion, is making a musical ascent: improvising so furiously on the higher chord tones of the elusive “Cherokee” harmonic progression that Pynchon himself loses control of his sentences just writing about it. The words go colliding and careening in the wake of notes they’re trying to capture. Slothrop and Bird—and, it seems, Pynchon—are all having out-of-body experiences. Ricks’s music captures this musical dream-state not only through the obvious and agitated ode of the alto sax and jazz combo instrumentation, and occasional pictorialisms—a gunshot is a gunshot—but also through the careful timbral dovetailing between live and electronic sound. The lines seem to swerve in and out of materiality. Also, like Pynchon, Ricks uses cinematic cross cutting to disrupt the temporal flow, and blurs the musical line through extended techniques and electronically-produced sonic afterimages. Towards the end there’s even a strong hint of a funeral knell—an allusion, perhaps, to Pynchon’s observation that hidden deep down in all of Bird’s solos one hears the Reaper going about his ‘‘idle, amused, dum-de-duming.”

In Beyond the Zero, Ricks looks again to Gravity’s Rainbow for inspiration. This time, Pynchon’s famous opening line becomes a musical onomatopoeia: “A screaming comes across the sky.” The high violin note, slowly and subtly augmented with electronics, assumes the role of the German V2 rocket—the novel’s primary object of obsession. It serves as a narrative obsession—for Pynchon, and. by extension, for Ricks—nor only because of its potential for physical violence, but for temporal violence, its ability to break apart time. The V2 would fly through the air at such a high supersonic speed that by the time you heard its aerial whine, it had already obliterated its target. This temporal elusiveness, this defiance of the minimal boundary of the now, resonates with Ricks’s title, which turns out to be twice-borrowed: Pynchon used the phrase for the subtitle of his novel’s first section after lifting it from Pavlov. The famous psychiatrist, unwittingly prophesying postmodern malaise, had used the phrase to describe how continued stimuli, once they have become overly familiar and no longer capable of eliciting reflexive response from a subject, actually reinforce non-responsiveness: the subject’s reflexes not only flatline, but descend into the realm of negative perception “beyond the Zero.” It is this breaching of ontological thresholds that fascinates Ricks; in fact, he leverages this postmodern permeability as a frame for religious mysticism. The electronically accompanied violin shuttles across the boundaries at either end of mortality: birth and death, both audible moments of transition within the piece. Ricks’s immortal imaginings thus bookend the extended midsection of the piece, which stands as a reflection on the turbulence of life on Earth.

Music

2. Mild Violence (8:02)

3. American Dreamscape (12:12)

4. Dividing Time (14:49)

5. Beyond the Zero (10:55)

6. Haiku (9:16)

Carlton Vickers—flute (1).

New York New Music Ensemble, James Baker: conductor (2).

John Sampen—alto saxophone (3).

Ron Brough—percussion (3).

Scott Holden—piano (3).

Eric Hansen—contrabass (3).

Steve Ricks—conductor (3).

John Sampen—alto saxophone (3).

Talujon Percussion Quartet (4).

Curtis Macomber—violin (5).

Dominic Donato—Tibetan prayer bowls, tam tam (6).

Additional Information

Pynchon on Record

Return to the main music page

Last Modified: 16 June 2022

Back to: Pynchon on Record

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact:quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com