Pynchon Music: David Ocker

- At January 11, 2021

- By Spermatikos Logos

- In Pynchon, The Modern Word

0

0

Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane & Galliard

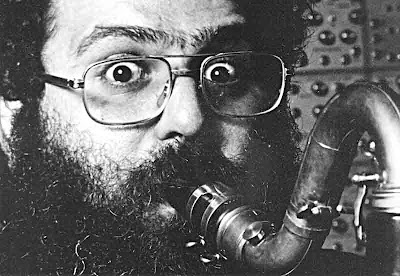

David Ocker (b. 1951)

David Ocker is a graduate of Carleton College (MN) and the California Institute of the Arts. He studied clarinet with Richard Stoltzman, Michelle Zukovsky, and Phillip Rehfeldt. His composition teachers included Morton Subotnick, Earle Brown, Stephen Mosko, and Paul Chihara.

Ocker was a founding member and later president of the Independent Composers Association in Los Angeles. He was also a founding member of Xtet, a chamber ensemble with a special interest in the music of the twentieth century. Called a “super-clarinetist” by critic Mark Swed, Ocker performed and recorded as soloist with the London Symphony Orchestra in the premiere of Frank Zappa’s Mo ‘n Herb’s Vacation. In 1985 he was soloist with the Berkeley Symphony in Carl Nielsen’s clarinet concerto. One of his solo recitals, given at New Music America, was broadcast nationally. His interest in improvisation has led him to create entire, spontaneous concerts with multi-instrumentalist Vinnie Golia. One such event was described by music critic Alan Rich as “a splendidly communicative encounter by two of this region’s most valued progressive musicians.”

The largest portion of composer David Ocker’s music is for groups of acoustic instruments, ranging from solos to orchestral works. In these pieces he draws heavily on his experience as a clarinetist. Ocker’s music, as described by the Los Angeles Times, “can intrigue, fascinate and entertain even the jaded listener. Eclectic in the most positive sense, Ocker reveals his influences—Brahms, Ives, Copeland and jazz—sometimes eloquently, always without self-consciousness.”

For example, Ocker’s works include a solo bass clarinet piece derived from a Brahms symphony, a solo bass piece in which the performer both sings and plays, a set of musical limericks, a five-hour tape environment and a computer program to generate music from fractals. His chamber work Pride and Foolishness has been performed on the Los Angeles Festival, the Pacific Contemporary Music Festival in Seoul, South Korea, and on the Monday Evening Concerts. When the California EAR Unit played Pride and Foolishness at the Cal Arts Contemporary Music Festival in 1988, John Henken described it as having “the dark grace of some jazz arrangements of Bach, compounded in equal measure of minor mode moodiness and insistent rhythmic swing.” Ocker has completed two works for chamber orchestra: Waiting for the Messiah and Melodic Symphony.

Ocker has also been very active preparing music by others for first performance or publication. Composers with whom he has worked closely on major projects include John Adams, William Kraft and Frank Zappa, for whom Ocker worked for seven years as copyist, orchestrator, librarian, and Synclavier programmer.

Ocker’s music has been performed by Xtet, the California Ear Unit, the Antenna Repairmen, and even a rock group (The Mope—now defunct). His chamber work Pride and Foolishness was performed on the Pacific Contemporary Music Festival in Seoul, South Korea.

Ocker’s extramusical interests include computers, cartooning, and writing. He is especially fond of finding creative alternatives to the usually prosaic form of composer’s program notes. A good example is his “Eight Facts About Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane and Galliard, A Piece for Cello and Piano.”

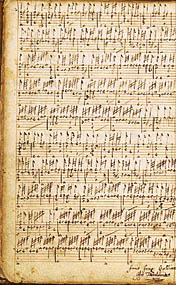

Eight Facts About Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane and Galliard, A Piece for Cello and Piano

Adapted from program notes (never used) for the premiere, April 23, 1988. Copyright 1988 David Ocker.

|

1. The first thing I decided

about this piece was the title.1 2. Next I researched exact definitions of a pavane (slow dance in four) and a galliard

(fast dance in six).2 3. The Galliard was finished on Groundhog Day. The Pavane was (almost) finished on Valentine’s Day.3

4. Thomas Pynchon (author of the novels V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow,

and Vineland) seems to have no connection whatever to Elizabethan dance music.4 5. Sixteenth-century composers are known to have preferred a harder edge between their pavanes and galliards.5

6. Roger Lebow, the cellist to whom this work is dedicated,

is a fan of Thomas Pynchon’s writings. So am I.6 7. Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony (a classic of his often-ignored minimalist period) seems to have no connection whatever to Thomas Pynchon.7

8. The last thing I composed in Thomas Pynchon, his Pavane and Galliard was the first note.8

|

1 It happened late at night. I used to take long walks from 11:00 p.m. to midnight on a predetermined course, in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles, just east of Hollywood. The actual idea probably occurred to me as I was approaching the intersection of Los Feliz and Griffith Park Boulevards from the south. This was the same corner where, on a different occasion, a woman crossed the street to avoid walking near me. She must have thought I was a rapist.

2 Actually, this involved little more than looking up the words in the Harvard Dictionary of Music, which I had purchased at a used bookstore (now closed) near the corner of Hollywood and Vine. The book is stamped “Purchased at USPS auction”. I wonder what circumstances would lead to the confiscation of a music dictionary. To my embarrassment, the Harvard Dictionary is the most complete musical reference work I own, but who can afford thousands of dollars for a set of Grove’s, even though it would be tax deductible. In short, I did just enough research to avoid being called foolish or stupid by experts in early music – but it is unlikely they would give much credence to my piece anyway.

3 According to the catalogue of my works published by Leisure Planet Music, Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane and Galliard was written in 1988. In fact, the Galliard was finished at 7:30 a.m. on February 2, just before my bedtime, but well after sunrise in Punxsutawney. The Pavane was completed at 3:30 a.m. on February 15, very late on Valentine’s Day. My first new music ensemble, the Bemidji Alliance, named after the piano player’s sister’s residence, gave its first performance on Groundhog Day in 1977.

4 I would naturally be happy to learn information to the contrary. I remember reading Gravity’s Rainbow on a United Airlines flight from Omaha to Los Angeles. A stewardess escorted an elderly lady to a seat right next to mine and said, “I’m sure this gentleman here would be a very good conversationalist”. I stuck my nose back in the book and didn’t say a word to her for the entire flight. Another stewardess saw what I was reading and exclaimed “Gravity’s Rainbow, I’m reading that. What a great book”. I still feel guilty for not talking to the old lady.

5 Because I wrote the Galliard first, I knew exactly what would follow the Pavane. The Pavane begins with a long note in the cello and simple chords in the piano. Gradually the tempo increases until the music returns to the beginning, only at a faster tempo. Once this section is played again, the music begins to slowly introduce elements of the Galliard. The actual moment the Pavane becomes the Galliard is not clear unless you are visually following the score. The Galliard is in two sections which repeat exactly. In a conventional galliard the six beats are usually accented into two groups of three, with the occasional hemiola: three groups of two. In my Galliard there are many measures which have five beats in them.

6 Roger and I both play in an ensemble called XTET, which currently has twelve members. Before this we played briefly in another ensemble called the Thirteenth Floor, formed especially to perform Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. Schoenberg was so afraid of the number thirteen that he died on Friday, September 13, 1951, at the age of 76. I wonder whether, had he lived another year, he would have died on September 14 at the age of 77. My father died at age 77, and I wrote a large set of chamber pieces in his memory, each of which has 77 measures in it. Thomas Pynchon has 107 measures in it, plus a pickup.

7 The piano part of the Galliard is fairly brimming with quotations from the first movement of Beethoven’s Eighth, one of my favorite pieces of music. Since the piano part is very contrapuntal, this is never particularly obvious. To throw people off the Beethoven’s Eighth scent, there is one very obvious quotation from Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony (“It’s over, it’s over, at last the storm…”), which the cellist is instructed to sing or whistle as well as play. Beethoven was unafraid to repeat motifs over and over again, transposing the pitch higher and higher to achieve a crescendo of tension and excitement. No one ever noticed that he had actually invented minimalist music in his Eighth Symphony because people listen to that symphony in the context of his other symphonies. Similarly, Ravel reinvented minimalism in his Bolero, but hardly anyone cares because the melody is so seductive. No one notices either that there is a quotation from Sweet Georgia Brown in the piano part of my Galliard. This is a good thing, because I have no reason to explain it.

8 The first full measure and the last measure of Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane and Galliard are nearly identical in content, although very different in function. This leads naturally to the notion that the piece could be played continuously for a very long time by repeating from the end back to the second measure without a break. This would be tiring for the performers and the audience. It would serve only to emphasize my own mind games, filled as they are with repetition, recursion, and the ultimate return to the source. Ultimately, I believe this notion has something to do with the writings of Thomas Pynchon, but I can’t prove it. That doesn’t mean I can’t believe in the connection. I know the Pynchon books inspired my little duet, because the first thing I decided was the title.

|

Mixed Meters —David Ocker’s eclectic blog.

David Ocker’s Facebook Page — The artists keeps a Facebook page.

David Ocker Discog Page — Collects album covers and information on David Ocker’s releases.

Program Notes— The program notes “Eight Facts About Thomas Pynchon, His Pavane and Galliard” were also published in Pynchon Notes 28-29, p.147-149.

Pynchon on Record

Return to the main music page

Author: Dr Larry Daw

Last Modified: 6 November 2021

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Last Modified: 6 November 2021

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com