Uncollected Pynchon: Liner Notes for “Spiked!”

- At January 13, 2021

- By Spermatikos Logos

- In Pynchon, The Modern Word

0

0

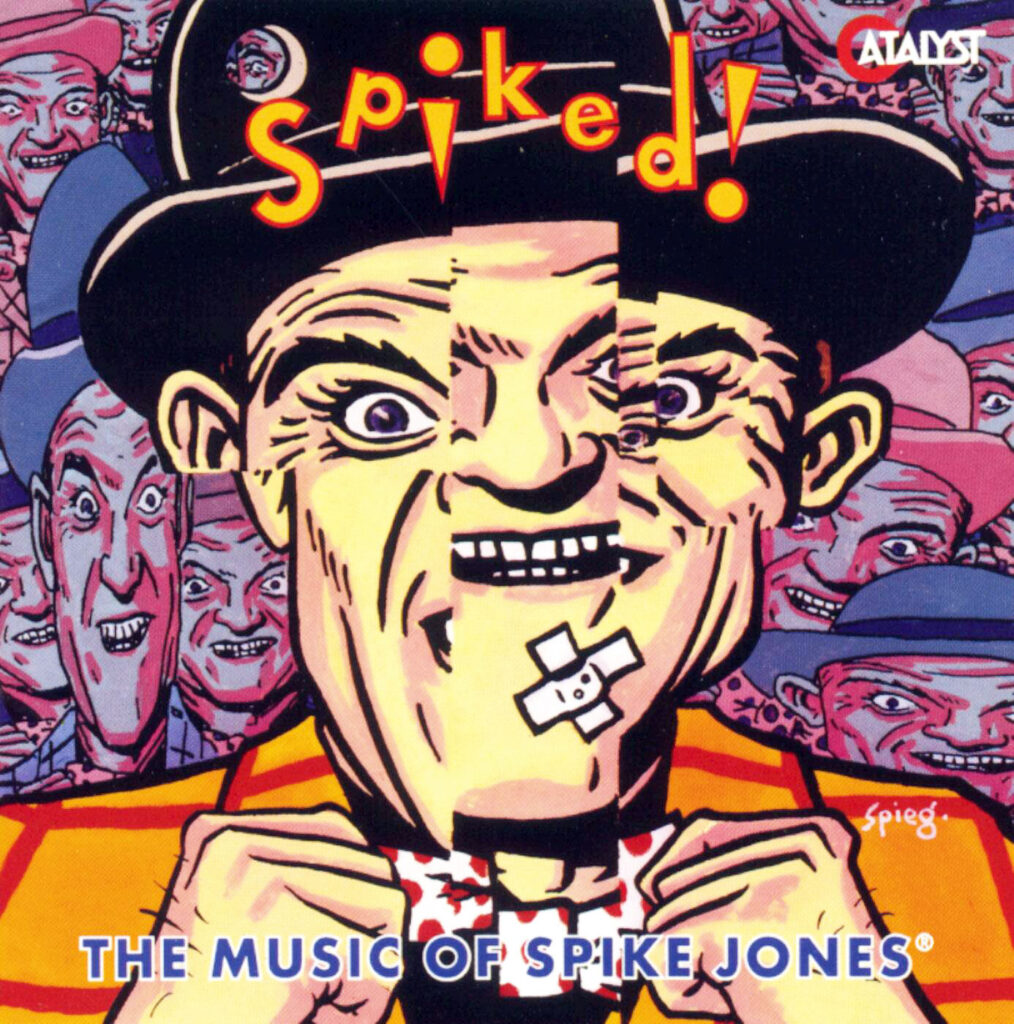

Liner Notes for Spiked! The Music of Spike Jones

Welcome, music lovers, to the cheerfully deranged world of Spike Jones and his City Slickers. There’s gunshots and cowbells aplenty, not to mention class hostility, first-rate musicianship, subverted expectations, hair-trigger timing, and more than enough material for that interesting subset of folks looking to be offended, who might like to begin, actually, with the lyrics to the recitative or lead-in to the “Chinese Dance” in Spike’s Nutcracker Suite—although mild compared to, oh say your average Chinese celebrity roast, this will require the sort of listener who either wants to wince with embarrassment or can find in vintage bigotry quaint refuge from the more virulent forms encountered in our own era. There is certainly lots of it here to go around. The “Russian Dance” makes fun of Russians. “Granny Speaks” is an insult to older people. Elsewhere, “Pal-Yat-Chee” manages to offend country people and Italians, “Deep Purple,” featuring Paul Frees’s impression of Billy Eckstine, will offend Afro-Americans because the singer keeps nodding off, implying narcolepsy not in the public interest, and so forth. What today we would unquestioningly call acts of racism seemed, for Spike and the Slickers and indeed postwar America, as pure and unpremeditated as the breathing of a Zen monk. It was the Golden Age of Radio, and dialect humor, a legacy from vaudeville and minstrel shows before it, was part of the comedy environment—shows like “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” “Life with Luigi” and “The Goldbergs” aired week after week, available for free to listeners not always analytical about what they were hearing. (Additionally, for musicians of the swing era, “Chinese” references in song lyrics had long been code for opium, its derivatives, and their recreational use—so there’s maybe that subtext here as well.)

All through this Nutcracker, in fact, runs a strange uneasy mixture of jaded musicians’ sarcasm and honest straight-world sentimentality. Nowadays, when everybody knows everything and nobody takes any text seriously, it’s hard to remember how it felt once to share a public world not as contaminated by the terminology wised-up irony that has come to pervade our own lives. People were still running on a residue of belief in movies, and radio, and pop music—as if there were an unspoken deal still in effect, despite the war, despite everything.When the Nutcracker album was released in November 1945, the war had just ended, and Christmas was around the corner, the first Christmas of peace. How could folks not be running on emotions, many of them even unknown to us today? Slicker irreverence here is so smoothed and controlled, it’s as if Spike considered the full-scale insanity of the band too intense, too adult, for the kid audience he wanted. Of course it wasn’t. Kids admired his records for nearly the same set of reasons grownups did—the rudeness, the grace of execution, the sheer percussive dementia.Yet there remains about Spike’s work what is sometimes almost anuncomfortable complexity. We’d like him to be simpler—how much can a purveyor of impolite sound effects comfortably be allowed in the way of depths? Traditionally, the drummer is supposed to be the weird guy, the holy fool, the lowest pulse, the one in touch with demonic forces and deep primitive brain levels—but not also, as in Spike’s case, a conceptual artist with a head for business. Early on, in ‘43, in a Radio Mirror interview, Spike described his band as “a subtle burlesque of all corny, hill-billy bands.” A great many of these City Slickers who were so hep to the jive had in fact themselves come originally from out in the middle of America, places like Thief River Falls and Oilton and Muncie—the Nilsson Twins hailed from Wichita, Sir Frederick Gas from Kansas City, George Rock from Farmer City, Illinois, and Spike himself from the farm and railroad environment of California’s Imperial Valley. They had all left these places, come to L.A., joined the union and embarked on nights of singular toil, playing live dates wherever Fate led and with luck now and then getting some movie, recording or best of all a radio gig, radio in this era having displaced the movies as the glamour medium, and L.A. throbbing along for those few hectic years as the syncopated heart of radio nationwide. Local 47 developed its own widely respected style—these were people who had to play things they had never seen before, and get it perfect the first time, or go on live before audiences in the invisible millions, and perform flawlessly. L.A. for a while was probably the center of the musical universe, Stravinsky living just off Sunset, Schoenberg teaching at UCLA, Charlie Parker and Miles Davis playing their historic gigs around South Central, nightclubs booming, radio stations broadcasting from them live, Zeidler & Zeidler doing phenomenal business in bop cardigans and porkpie hats, the whole town hopping, the pace swifter and louder than we usually think of in connection with California. Spike turned out to be one of the bright foci of all that energy, stepping, as a consummate and paid-up percussionist, into the sudden worldwide lull that followed the years of explosive destruction, from whose audio vernacular of course would be drawn the tuned gunshots, and Slickers screaming and running around, destroying sets, appearing to thrust various props into or through their heads, acting our the most lowbrow of musical impulses.But at the same time here was this strong attraction to the more refined world of the classics. Spike told an often-reworked story about going to hear Stravinsky conduct The Firebird at the Shrine Auditorium in L.A. Stravinsky is wearing some new patent leather shoes, and Spike is sitting close enough to notice that every time the composer-conductor goes up on his toes just before a downbeat, the shoes squeak. “Here would go the violins,” as he told it, “ and ‘squeak squeak’ would go his shoes. He should have worn a pair of sneakers. And the pseudos who went down to see the ballet, they didn’t know what they were looking at anyway. They thought, Stravinsky’s done it again. New percussive effects.” But then later, driving home, Spike gets to thinking—“ . . . if you made planned mistakes in musical arrangements and took the place of regular notes in well-known tunes with sound effects, there might be some fun in it.” The Stravinsky story sheds light from a couple of angles. Though the evidence suggests that the development of the Slicker concept was a little less closely thought out than this, still, with Spike in control of the rewrite, it was how the sound should have originated, how it will have to be shown in any eventual movie of Spike’s life—rational planning plus painstaking execution equals the raving musical insanity America came to love. Unable to respect highbrow audiences, Spike nonetheless wanted to claim inspiration from highbrow music. Both wanting and rejecting these connections at the same time seemed to generate a useful energy that’s audible in projects like the Nutcracker, and in what was perhaps Spike’s best shot at a class act, the Other Orchestra. Strings in those days meant not only Class, but also Cash, what with catgut aggregations like Percy Faith and Hugo Winterhalter soon to be topping charts week after week. But the Other Orchestra venture, by all accounts, was not a success. By as early as 1943 Spike had already been trapped, typed as the “King of Corn,” originally an insult title applied to Guy Lombardo. Announcing the O.O.’s formation, “I am fed and gorged, stuffed and bloated,” he told the press, sounding, strangely, like snooty columnist Waldo Lydecker in Laura (1945) “with being called the King of Corn. It takes crack musicianship to be a City Slicker. . . . Maybe my new band will change the minds of a lot of morons who vote for us in DownBeat’s poll year after year.” “Corn” by then had come to mean making fun of hillbilly music, which was enjoying a sudden boom, as talents like Bob Burns, Judy Canova, and Dorothy Shay, all of whom Spike worked with, took over a good part of the airwaves. Hillbilly was an idiom asking to be satirized—the regional accents alone beckoned to vocal impressionists at all levels of ability. But it’s not certain if Corn really ever got to be a full-scale genre, even though there was an annual DownBeat award for it, and serious magazine articles that tried to define it. Today, at a distance of nearly 50 years, it looks more like some labelling reflex—Spike was successful, in all of the established media plus early television, so somebody had to come up with a category that could account for him. The excesses and longueurs of Corn, in any case, are more than compensated for by the briefness of its existence as a trend.There’s a photo of Spike being crowned DownBeat’s King of Corn for 1944, by the Nilsson twins, who were a pleasant-looking young vocal act, regulars on Slicker tours. The coronet on Spike’s head is a standard costume-house model, featuring metallic points behind which are somehow wedged four erect, slightly oversize corncobs. Around his neck is a crude garland of even more corncobs. Spike is glaring, his legs tightly crossed, his mouth in an O. his eyes focused far, far away. The Twins are smiling and wearing these really cute checkered, maybe even gingham outfits, coded to suggest rural America. Here are all the outward and visible signs of the identity problem Spike seemed to be having right then. Still thinking of the Slickers as a novelty act destined only for some brief moment of fame, “We’ll just keep going,” he told Radio Mirror in 1943, “until people get sick to death of us and then it’ll be over.” He knew who he was, where he thought he wanted to go musically, and yet here was this ghostly teeming population of listeners who kept forcing upon him a kind of clown role he wanted to get beyond. Some king! So to augment the Slickers he went out and hired ten string players, plus about 20 other assorted reeds and brass, putting in $30,000 of his own money, and they opened at the Trocadero, a big nitery on the Sunset Strip, on 21 March 1946, as the Other Orchestra. In his autobiography Papa Play for Me, klezmer clarinetist and Slicker glug specialist Mickey Katz recalled Spike wanting “a symphonic jazz orchestra like Paul Whiteman. . . . No funny stuff, just beautiful music. And do you know what the crowds who came in said? ‘What kind of crap is this? If we want a symphony, we’ll go to the Holly wood Bowl. We came to hear Spike Jones, not Stokowski.’“ The public thought they knew who he should be. It must have felt strange in that room through the spring of ‘46, up every night in front of people one could not entirely relate to, even if it was a dream gig, with exactly the kind of material, white society-band pop music, that the Slickers had already made wicked brilliant fun of in “Cocktails for Two” and a little later, about six weeks into the Troc engagement, in “Laura.” The song had been featured the 1945 movie of the same name, supposed to evoke this hotsy-totsy social life where all these sophisticated New York City folks had time for faces in the misty light and so forth, not to mention expensive outfits, fancy interiors, witty repartee—a world of pseudos as inviting to Slicker class hostility as fish in a barrel, including a presumed audience fatally unhip enough to still believe in the old prewar fantasies, though surely it was already too late for that, Tin Pan Alley wisdom about life had not stood a chance under the realities of global war, too many people by then knew better. “The people want to laugh in war time,” Spike said. “Soldiers just don’t go for stuff like ‘Over There.’ They want sentimental stuff or strictly comic. We give ‘em the comedy, and it’s what the public goes for, too.”

As this apparent postwar loss of faith in the pop-lyric consensus deepened, along came a surge of music about music, the genre in which Spike was to become a master. This impulse to kid has of course been around a good while, at least as long as Mozart’s Ein Musikalischer Spass (A Musical Joke), K. 522, of which one Mozart biographer, in a line which could have applied equally to Spike, says, “Seldom in music has one mind exerted itself so much to seem so mindless.”

Besides the kind of intertextual hijinks represented perhaps at their most relentless here by “Pal-Yat-Chee,” there also appeared about then an epidemic of songs referring to themselves, as if direct emotional experience could not longer be trusted—again and again, like “Begin the Beguine,” “Stardust,” or closer to Spike’s area, “San Antonio Rose,” some piece of melody, presumably the very melody the lyric is at the moment being sung to, evokes a night of tropical splendor, a garden wall where stars are bright, a moonlight trail by the Alamo, and all at once, it seems, the lyric is about the melody.

Spike’s preferred structure was first to state the theme in as respectably mainstream a manner as possible, then subversively descend into restatement by way of sound effects, crude remarks, and hot jazz, the very idiom Spikes Jones and his Five Tacks had begun with back in high school, to the great displeasure of their parents. But used this way, dropped into like a lower gear, with antiquated licks and growls and semi-liquid vulgarities in the lower brass, not even the music of Spike’s own apprenticeship was to escape Slicker disrespect, having come to be code for, “Vulgar, ain’t it, compared to that society stuff,” at the risk of de-emphasizing what were brilliant ensemble performances.So it should come as no surprise to find among the Slicker oeuvre yet another form that refers to itself—the Knock-Knock joke, part of whose appeal lies in the metacomical point that somebody is being silly enough to tell it in the first place. “Knock-Knock (Who’s There),” may be the first surfacing into recorded form of this message from the underworld of child wit. Though few of its punch lines surprise as much now, back in 1949 they were sweeping playgrounds and candystore lounging areas like major low-pressure troughs. It is only a short sideways step from here to other Slicker performances that make simultaneous commentary on themselves—the addled lounge comedy of Doodles Weaver, the piping child’s voice issuing from oversized adult George Rock, the digestive punctuations of Sir Frederick Gas. For these and other Slicker virtuosi, “Knock-Knock” serves as a sample showcase.Weaver is also featured vocalist on “The Man on the Flying Trapeze,” where he exhibits much of the antic appeal that led to groups of Weaver cultists showing up on the nationwide “Musical Depreciation Revue” tour itinerary, places like Hutchinson, Kansas, travelling miles to greet him, barking like seals, from the front rows. The barking routine had been part of Weaver’s kit since his undergraduate days at Stanford, where he became legendary, once being unveiled in front of distinguished alumnus Herbert Hoover at the official campus dedication of a statue, cradled in the statue’s arms and doing his seal impression. This “Trapeze” cut, with its frantic Spoonerizing, self-interrupting to retune, laughing at his own jokes, is a classic Doodles Weaver performance. George Rock usually did child characters, his most famous being the one that sings “All I Want for Christmas is My Two Front Teeth,” which has continued every year to get some seasonal airplay around the nation. But now and then, like some musical Larry Talbot, he was able to assume his other persona with the Slickers, that of an adult trumpet virtuoso. His reliable showstopper was always “Minka,” which Jones’s bio-discographer Jack Mirtle estimates Rock played an average of once daily for ten years with the Slickers, though he had been playing it earlier with Freddie Fisher’s “Schnicklefritz” band. When he changed bands, he evidently brought “Minka” with him, a romantic set which, if anybody tried it today, would draw the immediate and avid attention of all lawyers within scenting distance. Sir Frederick Gas’s first appearance was a purely fictitious name that Spike, just for fun, thought would look interesting on the label of the already very strange “Our Hour,” (which depending on brain pathways, chemical permutations, and so forth can elicit a broad range of reactions. The dogsounds are by Dr. Horatio Q. Birdbath, alias A. Purves Pullen, another star Slicker, who specialized in animals and had the distinction of doing the voices for what are arguably the two greatest chimp characters in film, Cheetah in the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan movies, and Bonzo in Bedtime for Bonzo, opposite former president Ronald Reagan.) It wasn’t until later that Earl Bennett was hired and gradually came to occupy, like helium in a Macy balloon, the full volume of Sir Frederick Gas. He also appears here on “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You,” Tommy Dorsey’s theme song with trombone work, both Dorsey-style and otherwise, by Joe Colvin, whose pants in the Musical Depreciation Revue used to go up and down in rhythm to his playing. The Revue, like the later television shows, was always as much a visual as an audio act, with Spike running around deploying his pistol shots like a symphony conductor waving a baton, giants, midgets, animals, and tapdancers chasing on and off the stage, Slickers in fright wigs, chicken outfits and suits of reckless plaid that did not come cheap, and the lady harpist on “Holiday for Strings” smoking a cigar. If this collection were the soundtrack from the film biography, what kind of an arc could we find between “Red Wing” (1940)—the City Slickers first recording—and “Frantic Freeway” (1961)? Hayseed comes to the big metropolis, starts out making fun of easy targets like Indian lovesongs (“Red Wing” was a brand of chewing tobacco), is presently going after other hayseeds, pseudos, society music, the classics, becoming with the years more and more wised up until the last we see of him he’s not there like the Flying Dutchman on the great urban ultimate—the freeway, cruising nowhere special, reluctant to come to any rest or closure, out there among the mobility. “Frantic Freeway,” like Raymond Scott’s “Powerhouse,” is part of an album project left unfinished—vocals and additional layers of sound were still to be added. But in the spareness of what we do have, with fewer distractions, we can hear at last how lucidly tuned the sound effects are, with car horns and screeching brakes each assigned a pitch and included in a melody, as if vehicular unpleasantness, the soul of the City, could be somehow redeemed by song. We can feel the old gang-of-idiots amiability still shining through. This is the way characters end up in Zen stories illustrating deep lessons, though as in Zen, wisdom cannot always be separated from a peculiar sense of humor. “My band’s got rhythm,” Spike said once, “and to it we add a guffaw. We get along by not taking anything serious.” Which, if not heavy duty prophecy, turns out at least to be his maniac’s blessing and gift, finally, to us, adrift in our own difficult time, with moments of true innocence, like good cowbell solos, few and far between.

Author: Thomas Pynchon

Source: Spiked! The Music of Spike Jones, Catalyst CD 1994

Return to: Uncollected Pynchon

Go to: Spermatikos Logos Spike Jones Page

Source: Spiked! The Music of Spike Jones, Catalyst CD 1994

Return to: Uncollected Pynchon

Go to: Spermatikos Logos Spike Jones Page

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com