Joyce Works: “Ulysses”

- At May 13, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

It is an epic of two races (Israelite-Irish) and at the same time the cycle of the human body as well as a little story of a day (life). It is also an encyclopedia. Each adventure (that is, every hour, every organ, every art being interconnected and interrelated in the structural scheme of the whole) should not only condition but even create its own technique. Each adventure is so to say one person although it is composed of persons—as Aquinas relates of the angelic hosts.

—James Joyce, Letter to Carlo Linati, 21 September 1920

Ulysses

Ulysses

By James Joyce

First Edition: Shakespeare & Company, 1922

This is the biggie! The book where a “day be as dense as a decade,” Ulysses has sent more first-time readers scrambling for cover than any work since Moby-Dick and before Gravity’s Rainbow. And why? Is it big? Yes. Is it difficult? At times, yes. Is it boring and dull? No—hell no! Is it impossible for the average person to read? Absolutely not! There are many people who claim Ulysses as their favorite novel, and not just English professors, literary critics, and cryptographers. Folks who enjoy the occasional best-seller, have a passing fondness for Taco Bell, and cried at the end of Titanic.

So what is Ulysses?

This page offers a synopsis of Ulysses, some notes about its structure and Joyce’s virtuoso prose, and advice for the first-time reader. This is followed by comments on the book’s unique history, including the charges of obscenity and a brief history of the “Joyce Wars.” The page ends with a guide to the major editions of Ulysses currently in print.

a little story of a day

—James Joyce, Letter to Carlo Linati, 21 September 1920

Synopsis

Published in 1922, Ulysses is a remarkably ambitious novel, a labyrinthine work of great humor and technical accomplishment; once denounced as obscene, frequently accused of being unreadable, and often declared the greatest novel of the twentieth century. Its plot is deceptively easy to summarize: during the course of a single day, three main characters wake up, have various encounters in Dublin, and fall asleep eighteen hours later.

The Characters

The youngest of the three characters is Stephen Dedalus, the sensitive, intellectual protagonist of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Having “exiled” himself to Paris at the end of Joyce’s first novel, Stephen has returned to Ireland to attend his sick mother. He begins Ulysses wracked with guilt, having refused his mother’s dying wish to pray by her side. Next is the indomitable Leopold Bloom, a middle-aged advertising canvasser and non-practicing Jew. Good-natured, thoughtful, and curious, Bloom frequently feels awkward around his fellow countrymen, Catholics and nationalists known for bravado and directness. Bloom is also painfully aware that his wife, a beloved local singer, is having an affair with her musical director. Which brings us to Molly Bloom. Earthy and voluptuous, Molly remains off-stage most of the novel, enjoying an adulterous afternoon. She appears to the reader only during the final chapter.

The Day

The “single day” of the novel is Thursday, June 16, 1904—special to Joyce because it was the day that Nora Barnacle, his future wife, made her fondness clear to him. (At Sandymount Beach. When they were alone. A “fondness” very, ah, handily clarified.) Joyceans refer to this day as “Bloomsday,” and often celebrate June 16 with toasts, public readings of Ulysses, musical events, etc. Or by posting James Joyce Web sites, for instance.

The Plot

Although Ulysses unfolds over a single day, as Leopold Bloom remarks, it’s “an unusually fatiguing day, a chapter of accidents.” Among other things, there’s a funeral, a birth, an adulterous affair, an episode of voyeurism, a near-beating, and a drunken spree through Dublin’s red-light district. These events transpire over eighteen chapters, generally called “episodes,” each covering about an hour of time.

We begin our morning with Stephen Dedalus. Renting an old tower by the seaside, Stephen awakes to the realization that he doesn’t much like his roommates, an irreverent wit named Buck Mulligan and a patronizing Englishman named Haines. As the day wears on, it becomes clear Stephen doesn’t much like himself, either; nor his colleagues, friends, family, country, or religion. Throughout the day, Stephen indulges in one argument after another, from lofty debates about Hamlet to self-loathing disputes with his own conscience.

Leopold Bloom, on the other hand, begins the day rather pleasantly, frying up a tasty kidney and taking a relaxing sojourn to the outhouse. Leaving his home on Eccles Street, he does a little shopping before visiting a public bath and attending a funeral. Bloom then goes about his workday, getting sidetracked here and there with distractions: getting chased from a pub by a bigot, masturbating surreptitiously to a young bather, and studiously avoiding his wife’s lover.

Later that evening, Bloom meets Stephen at the Holles Street maternity hospital. Upstairs, a woman named Mina Purefoy is giving birth; while downstairs, Stephen and his buddies are having a grand tipple. Casually adopting the role of surrogate father, Bloom remains with his reckless young friend for the remainder of the night. Their adventures culminate in a brothel, where a defenseless chandelier pays the price for Stephen’s drunken epiphany.

After rescuing Stephen from the surreal violence of “Nighttown,” Blooms brings him back to Eccles Street for an exhausted, late-night conversation. Stephen declines the offer of a spare room and heads home. Bloom slips into bed with Molly, flush from her day of erotic exploits. As Bloom falls asleep, the narrative passes over to Molly, who’s remained conspicuously “off-stage” until this point.

Ulysses concludes with Molly’s “soliloquy,” a dreamy reverie animated by her sensual appetites: sex, love, travel, food, music, and the sheer pleasures of the material world. Lovers past and present are compared and contrasted, from the size of their organs to their habits with the chamber pot. While Molly can seem easily annoyed and delightful bitchy, she’s also generous, passionate, and forgiving. Despite her awareness of Bloom’s many faults—and her own faithlessness notwithstanding!—Molly reminisces fondly about their distant courtship. Her reverie culminates in one of literature’s most celebrated sentences, a joyous affirmation of life and love.

Total time and distance from the entrance of “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan” to Molly’s final “Yes”—Eighteen hours and 783 pages. At 1.38 minutes per page, that’s a well-documented day!

Our national epic has yet to be written… We are becoming important, it seems.

—James Joyce, “Ulysses”

Structure and Correspondences

Understanding the characters and plot of Ulysses is only half the story. Joyce wanted his “Blue Book of Eccles” to be something grander than the simple narrative of a day. When discussing the book, Joyce used words like “epic,” “adventure,” and “encyclopedia.” To realize these bold ambitions, Joyce wove his text upon a vast loom of hidden “correspondences,” an organizing framework of internal connections and external allusions. The most important of these are the Homeric parallels.

Relationship to Homer’s Odyssey

As suggested by its title, Ulysses is founded on The Odyssey, Homer’s tale of Odysseus and his travels after the Trojan War. (The Roman name for Odysseus is “Ulysses.”) In Homer’s epic, it takes ten years for Odysseus to return home to Ithaca, where his faithful wife Penelope has been fending off opportunistic suitors with the help of her son, Telemachus. During this time, Odysseus and his (ever dwindling) crew of (remarkably ill-behaved) sailors experience one adventure after another: fighting the Cyclops, avoiding the Sirens, being turned into swine by the sorceress Circe, and pissing off every minor and major god in the pantheon. Finally Odysseus returns home and slaughters everyone standing in the way of his family reunion.

Joyce uses The Odyssey as an ironic framework for Ulysses, with Bloom as the “heroic” Odysseus, Stephen as his “son” Telemachus, and Molly as the “faithful” Penelope. Although the eighteen episodes are not named within the text, literary tradition—with some prodding from Joyce himself—has assigned them titles inspired by The Odyssey, many with satirical connotations. Consequently, Ulysses doubles as a parody, a “mock-epic” populated by anti-heroes. This isn’t to say that Joyce ridicules his main characters, least of all Leopold Bloom, his “usyless” Everyman and Noman. Ulysses is never cruel or mean-spirited; it’s not even sardonic. Joyce reveals the nobility of his characters through their very failure to measure up to heroic standards, and its pages are filled with moments of great tenderness, love, and forgiveness. If asked to associate one quality with Ulysses, I would say “humanity.”

Other Correspondences

Well, that and “complexity,” perhaps! As mentioned above, Joyce wanted Ulysses to serve as an “encyclopedia.” While the Homeric parallels are the most important structural device, each chapter is also organized around a different hour, color, sense, symbol, art, science, bodily organ, and literary technique. Granted, most of these correspondences are invisible, even to the most attentive reader, and only become apparent after repeated study and analysis. Or, one can always consult the Ulysses “schema,” a map of correspondences “leaked” by Joyce in 1920. (So much for paring your nails, Jim.) These correspondences are intended to remain beneath the surface, providing internal dynamics and enhancing a narrative fully engaging on its own. Fortunately, there’s no reason a first-time reader needs to have Joyce’s schema memorized to enjoy Ulysses. After all, you don’t need to understand sonata form and harmonic theory to take delight in a symphony. But for readers who enjoy solving puzzles, a deeper appreciation of Ulysses awaits the curious investigator!

his usylessly unreadable Blue Book of Eccles

—James Joyce, “Finnegans Wake” 179.26-27

Prose, Style, and Narrative

Ulysses is famous for many things, from its complex structural tropes to its avowed difficulty, from its brilliantly-realized characters to its notorious “obscenities.” But what elevates Ulysses to the keystone of literary Modernism is Joyce’s revolutionary prose, a combination of protean flexibility and stream-of-consciousness immediacy. In Ulysses, the narrative doesn’t merely convey the story, it’s an active collaborator, rotating through a kaleidoscope of styles to illuminate alternate meanings, ironies, resonances, and counterpoints within the text. Like Picasso painting a portrait from multiple perspectives, Joyce playfully distorts his medium to capture the whole picture. When Stephen muses on the beach, the narrative is as abstruse and fleeting as his rambling thoughts. Later, when young Gertie is preoccupied with her own seaside dreaming, the girlish prose sprouts the flowery embellishments of a romance.

While precursors to this style may be traced as far back as Tristram Shandy in the eighteenth century, Joyce’s inventiveness places him firmly in the vanguard of literary Modernism. What started with writers such as Laurence Sterne, Herman Melville, and Henry James came to fruition with Virginia Woolf, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, and James Joyce. These writers believed that prose should be malleable, whether reflecting the impressions of a protagonist, challenging the notions of poetic structure, or establishing a playful relationship between author and reader.

Joyce began such experimentations in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and the first few episodes of Ulysses are comfortably intelligible to a reader familiar with Portrait. But as the novel progresses, Joyce takes increasing liberties with the narrative. A whirlwind tour of a printing press is bracketed by blustery headlines, while the conversations of fervent nationalists are mocked by epic forms. The musical “Sirens” episode begins with a linguistic overture, the chapter developing across a dazzling array of transposed musical forms in its attempt to render prose into music. But it’s “Oxen of the Sun” that draws the most praise—and bafflement. Here, where our heroes come together at the maternity hospital, the narrative reflects the birthing process, a sympathetic pregnancy that recapitulates the development of the English language. Like a growing fetus, the prose evolves from a zygotic fusion of Anglo-Saxon and Latin through nine stages of development, each represented by stylistic parodies of celebrated authors from Milton to Swift. The episode concludes with a raucous birth-cry, a thunderous eruption of modern polyglot slang that anticipates Finnegans Wake.

But even after this, Joyce has more tricks up his sleeve. Considered the climax of the novel, “Circe” is a phantasmagoric, Walpurgisnacht in which the day’s themes are reintroduced, exchanged, remodulated, and brought to varying degrees of resolution. Joyce stages this episode in the form of a surreal play. Dublin’s red-light district becomes a stage upon which Bloom’s innermost thoughts, fears, and fantasies are brought to life with hallucinatory detail, complete with monstrous chimeras and a black mass!

And yet, Joyce saves the best for last. Ulysses ends with “Penelope,” the episode where we finally “meet” Molly Bloom, tumbled directly into her predawn consciousness. Here, the narrative becomes a river of language, a mazy, winding soliloquy overflowing punctuation and syntax. Time, space, and identity dissolve under this dreamy current, a winding poem that climaxes with one wonderfully repeated word: yes.

Advice for the First-Time Reader; Or, in the words of Tim Conley:

IN CASE OF JOYCE BREAK GLASS

Ulysses may be wonderful, but unlike Moby-Dick, it’s genuinely earned its reputation for difficulty! If you want to approach Joyce’s masterpiece with a determined gleam in your eye, there’s some things you can do to prepare.

Budget the Time

First of all, accept the fact that you’re about to undertake a “project.” Clear your reading calendar for the next few months. Ulysses is enjoyable and rewarding, but it’s not this month’s book club selection, to be casually skimmed the night before meeting over drinks and friendly debate.

Embrace Confusion

No one understands the entirety of Ulysses, especially not the first time through. There are Joyce scholars who remain confused by certain opaque passages, or continue to debate the meaning of ambiguous word choices. Every first-time reader will have moments of confusion and frustration. At times, you may even feel stupid, irritated, or hostile! As long as you’re still enjoying the overall experience, don’t worry about understanding every single sentence. Just keep reading, and trust that things will make more sense just around the corner. Like any meaningful endeavor, reading Ulysses requires some patience. There will be setbacks and moments of doubt, but it truly is worth the effort.

Pick Up a Guidebook

Joyce loves his allusions. Ulysses contains thousands of references to real-world locations, political figures, religious ceremonies, advertisements, popular songs, and newsworthy events. There’s also numerous phrases in other languages, particularly Gaelic and Latin. Not only that, but the book’s very structure—the Homeric parallels and schema correspondences—are hidden from view.

The best way to make sense of this is to get a good Ulysses guidebook. There are many such works available, and you can read summaries of them on the Brazen Head’s “Ulysses Criticism” page. While they all have their pros and cons, there are two in particular I’d recommend to a first-time reader. The first is Patrick Hasting’s Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses. A refreshingly readable book written for a first-time reader, Hastings’ guide offers a chapter-by-chapter walkthrough of Ulysses. Confused about the plot? Check Hastings! (I used to recommend Harry Blamires’ New Bloomsday Book, but I feel Hastings is more accessible to the modern reader. Though Blamires is still a solid choice!) My second recommendation is Don Gifford’s Ulysses Annotated. Essentially the Ulysses Bible, this monumental work explains the structure and correspondences in Ulysses, and offers precise annotations for every reference and allusion. It may be the size of a phonebook, but it’s worth having by your side. For online help, you can’t beat Patrick Hastings’ Ulysses Guide, a comprehensive site that offers advice for fist-time readers, helpful essays, and detailed summaries of each episode. (Hastings’ site came before his book, but it’s still actively maintained.)

Prerequisite Reading

For readers fully determined to climb Mount Ulysses, a little literary prep-work pays off handsomely when making the actual ascent. While this so-called “prerequisite reading” isn’t strictly necessary, readers familiar with the following works are in a better position to find footholds in Joyce’s daunting narrative.

Dubliners & Portrait

All of Joyce’s books are related; set in a single, fictionalized Dublin populated by recurring characters and themes. Each book is set after the previous book, and often contains references to things that occurred in earlier stories. If you want to get the most out of Ulysses, read Dubliners first, then A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Both contain characters and events that are referenced in Ulysses. Of the two, Portrait is more important, as it introduces Stephen Dedalus. If Ulysses is The Lord of the Rings, Portrait is The Hobbit.

The Odyssey

As described under “Structure,” Joyce uses Homer’s epic as a template for his main characters and narrative episodes. You don’t have to read The Odyssey to understand Ulysses, but even a quick trip to Wikipedia can be useful. An understanding of each chapter’s Homeric counterpart unlocks a world of delightful allusions, intriguing associations, and delicious ironies, further enriching one’s appreciation of Joyce’s sprawling masterpiece.

Hamlet

Shakespeare’s great tragedy casts a long shadow over Ulysses. Hamlet is discussed at length by several characters throughout the novel, particularly during the “Telemachus” and “Scylla and Charybdis” episodes. Reading Shakespeare’s play or watching a cinematic adaptation before reading Ulysses makes these sequences more intelligible and rewarding.

“Who Goes with Fergus?”

The final reading is also the shortest: “Who Goes with Fergus?” Yeats’ lovely poem surfaces from time to time in Stephen’s mind, and its imagery occasionally floats through the narrative.

Join a Reading Group

Many people find that reading Ulysses is more rewarding—or less intimidating!—in the company of others. I highly recommend joining a Ulysses reading group. Unlike most book clubs, which meet every month to discuss a different book, Ulysses groups usually discuss individual chapters. Some groups “rush” through the book in eighteen weeks, while others take a more leisurely approach, often pacing themselves at one chapter per month. If you can’t find a local Ulysses reading group, consider starting your own. More people than you might think are interested in reading Ulysses, and starting a group could be just the stimulus they need. Try printing out ads and hanging them in local libraries and bookstores.

If you can’t find other interested people, or meeting in person just isn’t your thing, you can always try the Internet. Many online communities host group readings of Ulysses, and they’re usually sympathetic to interested newbies.

It sounds to me like the ravings of a disordered mind—I can’t see why anyone would want to publish it.

—Judge McInerney, 1920

DEAR DIRTY DUBLIN

Before discussing the various editions of Ulysses, a few words about its famous naughtiness may be in order. Even today, people still associate Ulysses with the obscenity trials it was subjected to in the 1920s and 30s. It’s remarkable how many people still consider Ulysses a “dirty book!”

The controversy starts four years before Joyce first published Ulysses as a novel. In March 1918, the American literary magazine The Little Review began serializing Ulysses, using manuscripts forwarded by Ezra Pound. Edited by Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, The Little Review already had acquired a reputation for pushing the boundaries of free speech. The fact it was published by a pair of Leftist lesbians didn’t help, and America’s puritanical authorities were looking for any excuse to bloody its nose. From the moment it rolled off the presses, Joyce’s writing was declared objectionable, and officials took delight in seizing copies of The Little Review and burning them like so many paper witches.

It was the publication of the “Nausicaa” episode in April 1920 that finally gave the censors the ammunition they needed. Here was a shocking scene of indecency, voyeurism, and masturbation! Being brazenly printed! And mailed to others! In the land of the free! The Little Review was charged with violating the Comstock Act of 1873, a puritanical law preventing the distribution of obscene material through the United States postal system. (With “obscene” also covering anything pertaining to birth control and abortion, by the way.)

The charges against The Little Review resulted in a highly-publicized obscenity trial. After a perfect charade of condescension, disingenuousness, and hypocrisy, three judges declared that Ulysses was obscene. Anderson and Heap were ordered to pay a $50 fine and to halt publication of Joyce’s blasphemous text. (For a sense of the proceedings, here’s a private comment made by John Quinn, their defense attorney: “I have no interest at all in defending people who…stupidly and brazenly and Sapphoistically and pederastically and urinally, and menstrually violate the law, and think they are courageous.” Quinn, who was actually one of Joyce’s patrons, had financial reasons for seeing Ulysses published, and had little love for Anderson and Heap. Reputedly, the two women were expecting to be jailed, and were disappointed by their comparatively mild punishment!)

In 1922, Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Company first published the entirety of Ulysses in Paris. That same year, a U.K. edition was published in England by Harriet Weaver’s Egoist Press. British authorities quickly banned the book, although numerous pirated editions began circulating.

Ulysses remained unpublishable in the United States until 1933, when United States v. One Book Called Ulysses declared Ulysses free from the sin of pornography. In fact, Judge John M. Woolsey produced an enduring comment on Joyce when he declared, “In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of his characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season Spring.” A year later, Random House published the first U.S. version of Ulysses. This was followed in 1936 by the first “legal” U.K. version, published by John Lane/Bodley Head in London.

For those interested in a deeper dive into the turbulent waters surrounding Ulysses, Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book focuses on the obscenity trials. There’s also Bruce Arnold’s The Scandal of Ulysses, which also covers the complicated publishing history of Ulysses up to the “Joyce Wars.” Which brings us to….

For that (the rapt one warns) is what papyr is meed of, made of, hides and hints and misses in prints. Till ye finally (though not yet endlike) meet with the acquaintance of Mister Typus, Mistress Tope and all the little typtopies. Filstup. So you need hardly spell me how every word will be bound over to carry three score and ten toptypsical readings throughout the book of Doublends Jined

—James Joyce, “Finnegans Wake,” 20.10–16

Which Edition?

Like most classic novels, there are many different editions of Ulysses on the market. You can find handsome hardcovers, budget paperbacks, annotated editions, abridged versions, illustrated versions the size of coffee-table books, and even a boxed facsimile of the 1922 original. Even more confusing, there are multiple versions of the text itself, and nobody agrees which is the most authoritative! Although a first-time reader will notice little difference between editions, it’s a fun little story to tell, so here’s a brief history of “The Joyce Wars.”

Before Joyce first published Ulysses as a novel in 1922, portions of it had already been serialized in magazines such as The Little Review and The Egoist. Preparing a single, definitive text for publication was no easy task. The book was enormous, the narrative experimental, and the typography unconventional. Worse, Joyce was an inveterate tinkerer, and revisions and rewrites were spread across numerous drafts, fair-copies, and typescripts. There’s also the fact that Joyce staved off penury be selling his manuscripts to any patron who showed an interest. Oh, and once the offended husband of a typist threw the manuscript of “Circe” into the fire! It’s no surprise that the original 1922 publication contained numerous errors!

Joyce oversaw several attempts to correct the text for further editions, but the fact the book was banned in the U.K., Ireland, and the United States was problematic, to say the least. He was also busy writing Finnegans Wake. In 1932 Albatross Press published a version with Joyce’s approval. A small publisher based in Hamburg with an office in Paris, Albatross was a pioneer in mass-market paperbacks, and specialized in German/English translations. It was also a major inspiration for Allen Lane’s Penguin books. In order to publish Ulysses, Albatross created a special imprint, Odyssey Press. The first Odyssey edition was based on the most recent Shakespeare & Company edition, with additional corrections and proofreading by Joyce.

Once Judge Woolsey declared Ulysses to be art instead of pornography, the book could be published without fear of legal reprisal. For the next few decades, there were several variants of Ulysses on the market, including the 1922 original and subsequent corrections, the Random House 1934 edition, four impressions from Odyssey Press ranging from 1932 to 1939, and several impressions of the Bodley Head edition, itself using the 1934 “second impression” from Odyssey Press. There were also numerous pirated and samizdat copies circulated by people afraid of running afoul the censors.

In 1961 Random House released a “corrected and reset” version of Ulysses. This edition was based on the 1960 Bodley Head text, which itself was based on Joyce’s approved second Odyssey impression from 1934. This new edition stood for over a decade, until a team of researchers headed by German scholar Hans Walter Gabler set their minds to producing an “improved” version. Returning to the original sources—reams of papers, scripts, drafts, early editions—Gabler worked from 1974-1984 to produce a “Critical and Synoptic Edition.” This was eventually published with great fanfare in 1986 as “The Corrected Text.” This edition was intended to replace all previous versions of Ulysses, which were removed from publication.

It didn’t take long for Gabler’s edition to come under fire, attacked by a team of Joyce scholars led by the American John Kidd, who claimed that Gabler’s “corrected” text was actually worse than the original. The debate between Gabler and Kidd became known as “The Joyce Wars.” Played out before a largely unknowing and indifferent public, the debate often descended into academic snark and ad-hominem attacks. Kidd accused Gabler of making numerous unsupportable decisions and willful interpretive errors, while the imperious German dismissed Kidd as an upstart incompetent. By the early 1990s, Kidd had made enough of an impact that Random House decided to keep both the 1961 and the 1986 versions in print, and the “Corrected Text” was downgraded to the “Gabler Edition.”

These two versions dominated the market until 2012, when the EU copyright on Ulysses expired. What made this particularly noteworthy was its impact on the Joyce estate. Presided over by James’ parsimonious grandson Stephen Joyce, the Joyce estate was known for its draconian protection of Joyce copyrights. It’s fair to say Stephen was not a beloved figure among Joyceans, denying most artists from using Joyce’s text and threatening legal action at the drop of a hat. (There’s few Joyceans, myself included, who hadn’t received a “cease-and-desist” letter from Stephen!) The expiration of the copyright opened the floodgates, allowing the publication of multiple “versions” of Ulysses. It also created a long, protracted legal headache, as each subsequent “version” of Ulysses after 1922 has various copyrights in different countries. Stephen’s death in 2020 has resulted in looser copyright controls, just in time for the Ulysses centennial.

So what does this mean for the average reader? Well, there are currently four major versions of Ulysses available, with more independent variations popping up all the time. Most of these “independents” are budget titles or illustrated editions, and are still based on one of the “big four” established texts. These “big four” are listed in order of original publication, with links to the most widely-known editions.

Ulysses: Major Editions

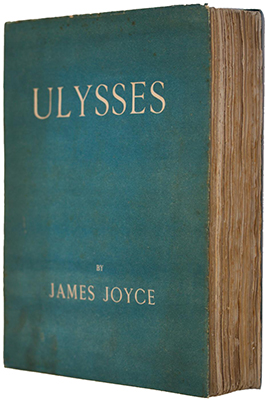

1922 Original Edition

Ulysses (Facsimile) By James Joyce Orchises Press, 1998 |

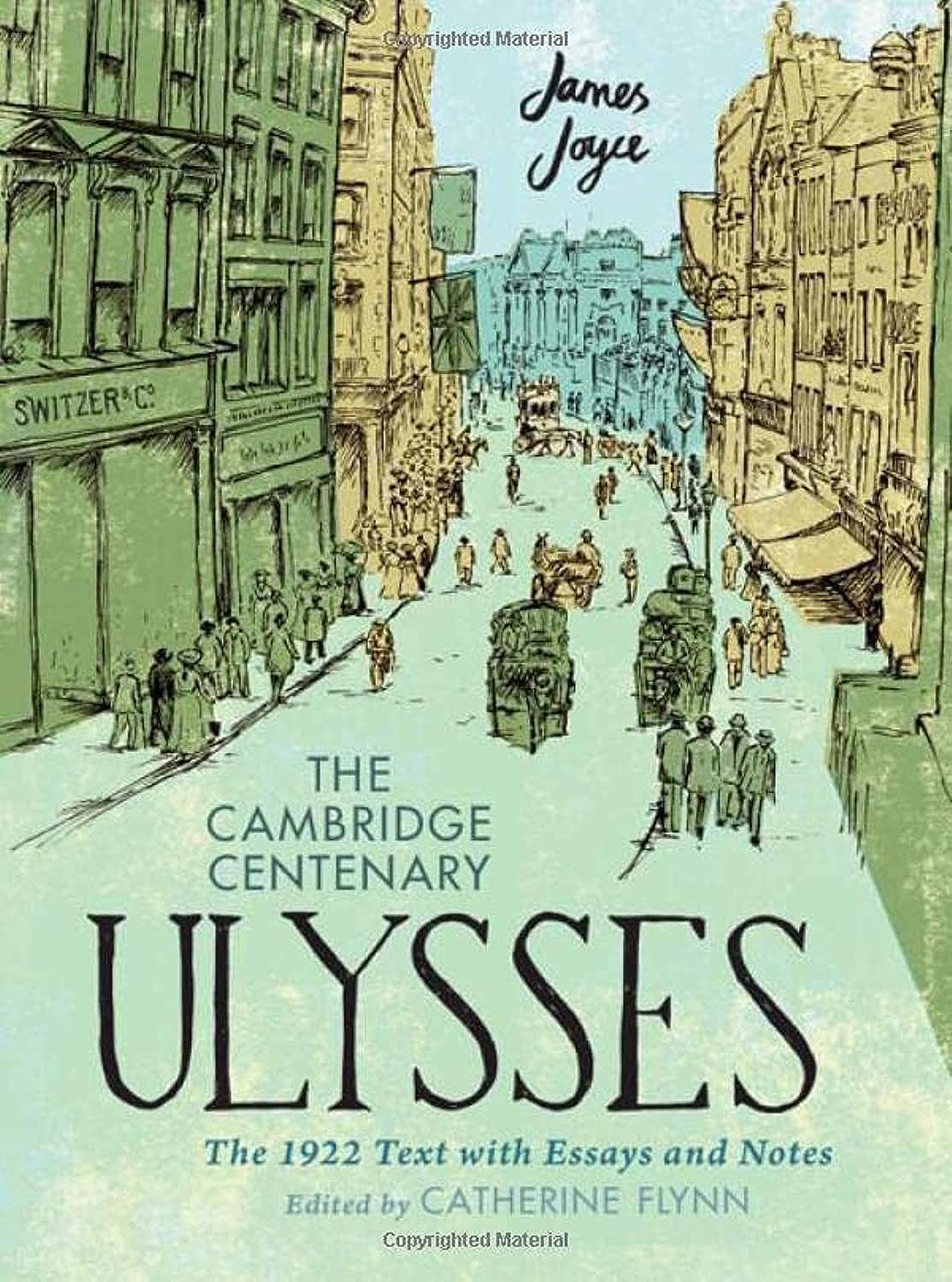

Cambridge Centenary Ulysses By James Joyce. Edited by Catherine Flynn. Cambridge, 2022 |

Filled with errors and omissions, the original 1922 edition of Ulysses is undoubtedly the least-read version on the market. While the upcoming Cambridge “Centenary Edition” is complete with errata and notes on future revisions, the 1998 facsimile from Orchises Press features the famous “Greek blue” cover and comes packaged in a lovely storage box. Sadly, it’s out of print, but you can still find (reasonably?) affordable copies on eBay and various used booksellers.

1939 Odyssey Edition

Ulysses: Annotated Edition

By James Joyce. Edited by Sam Slote.

Third Edition: Alma Classics, 2019

The fourth and final impression from Odyssey Press, this is the last edition of Ulysses to be proofread by James Joyce himself. It’s available through Alma Classics, who have coupled the text with annotations by Sam Slote, Marc A. Mamigonian and John Turner. A nice history of this edition is provided by William Brockman for Variants.

1961 “Corrected and Reset” Edition

Ulysses By James Joyce Modern Library, 1992 |

Ulysses By James Joyce Vintage Paperback, 1990 |

Based on the 1934 Odyssey Edition, the 1961 “Corrected and Reset” edition is immediately recognizable for the huge black letters that begin each section of the book. This is the edition that was pulled from the shelves from 1986 to 1990. The two most common versions are the Modern Library hardcover and the Vintage paperback, which continues their tradition of ugly Joyce covers. (Though the “yes” is a nice touch.) The 1961 edition is my preferred version of Ulysses, as I essentially agree with many of Kidd’s criticisms of the 1986 Gabler edition.

1986 Gabler Edition

Ulysses

By James Joyce

Vintage Paperback, 1986

Its star having faded since the 1990s, the Gabler Edition has more frequent line numbers, and the chapters are clearly numbered; but it doesn’t have those nifty capital letters of the 1961 version. Unfortunately, the most common U.S. Gabler edition is the Vintage paperback, the one with the horrible cover that looks like a Colorforms nightmare. (An astute reader may note that because Vintage and Modern Library are both imprints of Random House, they’re covering all their bases here!)

Ulysses: Selected Other Editions

The Little Review “Ulysses”

The Little Review “Ulysses”

By James Joyce. Edited by Mark Gaipa, Sean Latham & Sam Slote

Yale University Press, 2015

This fascinating volume collects the original serialization of Ulysses in The Little Review. It covers most of the published novel from the opening “Telemachus” until partway through “Oxen of the Sun,” after which the courts order the magazine to halt publication on account of obscenity. The original text is accompanied by a thorough introduction, illustrations and facsimiles, and several essays about the magazine and its relationship to Ulysses.

The writer Bob R. Bogle, author of Up the Creek, shared this review with the Brazen Head:

There’s a big difference in the experiences of binging an old TV show and when we originally watched it unfold in real time back in the day. It’s hard to conceive of what it must have been like to read Ulysses in serialized form during the period March 1918 until December 1920, when the serialization was terminated because of what was deemed obscene at the time. Readers of the Little Review didn’t even get to read to the end of Ulysses; its first authorized edition (by Random House) would not be legally published in the United States until 1934, and a more accurate version would not appear before 1961.

The Little Review “Ulysses” contains a transcription, with an attempt to preserve all the errata and editorial censorings, of the serialized version that appeared in the Little Review. This incomplete text is not a version appropriate for the first-time reader, but for persons very familiar with the text who are interested in this phase of its history. The text of Ulysses that appears here speaks for itself, and my focus is on accompanying essay material.

We get quite a bit of information about the roles played during this period by important players such as Ezra Pound, Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap and, to a lesser degree, by John Quinn. Most, or all, of the historical background concerned with the writing of Ulysses can be found elsewhere; however, it is of course entirely pertinent for it to appear here. “The Composition History of Ulysses” section reminded me again (I’d never really forgotten it) how much I value and admire Michael Groden’s masterful 1977 study, Ulysses in Progress, which is amply quoted here. If you’re a student of Joyce, Groden’s book is a must-own. On the other hand, if you haven’t yet read Groden, then this section of the book will be like a revelation to you. “The Composition History of Ulysses” is like condensed Groden, dealing only with the part of the story through the Little Review experience. It was interesting to me to learn just how much Pound and Anderson did their best to censor Joyce prior to publication of various issues of the Little Review. Eventually material too central to the story would inevitably have to be retained, at which point continuing publication in pseudo-Puritanical America was doomed.

I’m more skeptical about the merits of the essay entitled “Joyce’s Magazine Network,” wherein an effort is made to compare (among other things) the content of each of Joyce’s contributions with the other stories and poems and articles coincidentally appearing in each particular issue. It is suggested that a revolutionary evolution of Modernism is unfolding in that time on those pages, a hypothesis I embrace, but the method of demonstrating this seems somewhat preposterous; after all, the assembly of articles appearing in any one issue happened to come together by luck, not according to some master plan seeking out shared themes. On the other hand, if you’re looking for material to support or disprove your hypothesis of a revolutionary evolution in literature, where better to look for signs than in a literary magazine? But maybe sometimes the focus is too close. If we zoom out and consider wider frames of time than on an issue-by-issue basis, it seems to me the case becomes more sustainable.

1997 “Reader’s Edition”

Ulysses: A Reader’s Edition

By James Joyce. Edited by Danis Rose.

Trans-Atlantic Pubns, 1997

In order to complete this modest survey, I should mention the 1997 “Reader’s Edition,” edited by Danis Rose. This abomination brazenly edits Joyce’s text, untangling his longer sentences, hyphenating his compound words, and punctuating Molly’s soliloquy. Needless to say, this is blasphemy to most Joyceans, so if you go this route, best construct a book-cover out of a brown paper bag and just write “ULYSSES” in Sharpie. Fortunately out of print, this edition was ill-conceived from the beginning, and pleased nobody. I’m sure Rose’s next project was the “Listener’s Edition” of Wagner’s Ring cycle, minus the tubas and dwarfs.

2022 Illustrated Edition

Ulysses: An Illustrated Edition

By James Joyce. Illustrated by Eduardo Arroyo.

Other Press, 2022

This new volume is a large, handsome hardcover illustrated by the Spanish artist Eduardo Arroyo.

Publisher’s Description: This strikingly illustrated edition presents Joyce’s epic novel in a new, more accessible light, while showcasing the incredible talent of a leading Spanish artist. The neo-figurative artist Eduardo Arroyo (1937–2018), regarded today as one of the greatest Spanish painters of his generation, dreamed of illustrating James Joyce’s Ulysses. Although he began work on the project in 1989, it was never published during his lifetime: Stephen James Joyce, Joyce’s grandson and the infamously protective executor of his estate, refused to allow it, arguing that his grandfather would never have wanted the novel illustrated. In fact, a limited run appeared in 1935 with lithographs by Henri Matisse, which reportedly infuriated Joyce when he realized that Matisse, not having actually read the book, had merely depicted scenes from Homer’s Odyssey. Now available for the first time in English, this unique edition of the classic novel features three hundred images created by Arroyo—vibrant, eclectic drawings, paintings, and collages that reflect and amplify the energy of Joyce’s writing.

Brazen Head Resources

Ulysses Criticism

A list of annotations, guides, and criticism published about Ulysses.

Offsite Resources

Project Gutenberg Ulysses

The online text of of the Shakespeare & Company 1922 Ulysses.

Ulysses Correspondence

This site allows you to search the Gutenberg Ulysses.

Joyce Project

John Hunt’s site contains the entire text of Ulysses on link, with hyperlinked annotations.

James Joyce Digital Archive: Ulysses

Edited by Danis Rose and John O’Hanlon, the JJDA “presents the complete compositional histories of Ulysses & Finnegans Wake in an interactive format for scholars, students and general readers.”

UlyssesGuide.com

Patrick Hastings’ wonderful “Ulysses Guide” is designed with the first-time reader in mind, a comprehensive resource that offers friendly advice, along with a detailed summary of each episode. Highly recommended!

Joyce Images

Aida Yared’s wonderful site contains an archive of photographs and illustrations keyed to the episodes of Ulysses.

One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses

This stellar Web site backs an even-more remarkable exhibit at the Morgan Library in New York City. The exhibit runs unto 3 October 2022.

Joyce Works:

[Main Page | Dubliners | A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man | Ulysses | Finnegans Wake | Poetry | Exiles | Other Works]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

First Posted: 16 June 1995

Last Modified: 17 July 2022

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com