Joyce Works: Poetry

- At May 24, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I, who dishevelled ways forsook

To hold the poets’ grammar-book,

Bringing to tavern and to brothel

The mind of witty Aristotle

—James Joyce, “The Holy Office”

James Joyce: Poetry

Although primarily known for his novels, Joyce produced a fair bit of poetry, most of it written during his early days in Ireland. His first published work was a collection of poems called Chamber Music, a volume that earned him a place in the Imagist Anthology and brought him the attention of Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Joyce was also fond of satire, and occasionally responded to critics by circulating broadsides among his Dublin friends and enemies (who were often one and the same!)

Joyce the poet favored lyrical themes. His early pieces are patterned after songs, particular the simple airs of the Elizabethan period. As he matured as a writer, his poems developed in complexity and subject matter. As Finnegans Wake began consuming his creative energy, Joyce wrote less and less poetry. His last poem, “Ecce Puer,” hails from 1932, almost a decade before his death.

As a novelist, Joyce remains an undisputed genius, and his lofty place in the annals of literature is quite secure. But as a poet, Joyce’s position is a little shaky, and he may be justly placed behind the great talents of his day—or, to be blunt, Pound and Eliot have nothing to fear! It’s not that Joyce was a terrible poet; on the contrary, he’s written a few verses which stand proudly next to his peers, and his satire stings with a Swiftian deftness. But taken as a whole, Joyce’s poetry lacks the insight that illuminates his prose, and often sounds like Yeats rushing to meet a deadline. On the other hand, there’s a guilelessness to his poetry that reveals a side of Joyce rarely glimpsed in his novels. Verses that might be dismissed coming from a more naïve writer sound almost endearing when penned by the hand that wrote Ulysses!

If you’re interested in reading Joyce’s poetry, several convenient volumes offer complete collections of his verse. Three of the most accessible are featured at the end of the page.

Joyce’s Poetry: Commentary

“The Holy Office”

“The Holy Office”

By James A. Joyce

Broadside, 100 copies, 1904

Available online at: Bonhams | Brazen Head

This scatological satire dates from 1904, shortly before Joyce was to leave Ireland and elope with Nora. It originally took the form of a broadside printed by Joyce and circulated among his Dublin circle. Intended to defend and clarify his artistic position, it took a well-aimed swipe at the narrow-minded people of Dublin, their refusal to face reality, and their predilection for art romanticized by the “Celtic Twilight.” Joyce’s biographer Richard Ellmann remarks, “with quick thrusts he disposes, more or less thoroughly, of his contemporaries. Yeats had allowed himself to be led by women; Synge writes of drinking but never drinks; Gogarty is a snob; Colum a chameleon, Roberts an idolator of Russell, Starkey a mouse, Russell a mystical ass.” Joyce, placing himself squarely in the tradition of Aristotle and St. Aquinas, reckons his writing as a purgative for Dublin’s bloated hypocrisy:

That they may dream their dreamy dreams

I carry off their filthy streams

For I can do those things for them

Through which I lost my diadem,

Those things for which Grandmother Church

Left me severely in the lurch.

Thus I relieve their timid arses,

Perform my office of Katharsis.

The satirist’s unflinching art is an honest mirror which reflects the things they would rather not acknowledge. The broadside declares the poet willing to pay the price of his “holy office”—that he must bear the brunt of their anger and hypocritical scorn, for that is the burden of all artists true to their principles, even if it leaves them

…self-doomed, unafraid,

Unfellowed, friendless and alone.

“The Holy Office” is a wicked satire, if not always fair to its targets. When one remembers that Joyce had the vast majority of his career ahead of him, it’s hard not to admire the arrogance of the attack, a swift strike from a lucifer match.

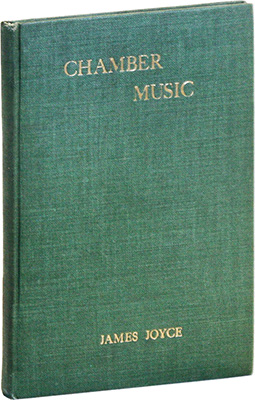

Chamber Music

Chamber Music

By James Joyce

Elkin Matthews, 1907

Available online at: Internet Archive | Project Gutenberg | Poets’ Corner

I hope you may set all of “Chamber Music” in time. This was indeed partly my idea in writing it. The book is in fact a suite of songs and if I were a musician I suppose I should have set them to music myself. The central song is XIV after which the movement is all downwards until XXXIV which is vitally the end of the book. XXXV and XXXVI are tailpieces just as I and III are preludes.

—James Joyce, Letter to Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer, 19 July 1909

Published in 1907, Chamber Music collects thirty-six untitled poems of a decidedly lyrical character. (Many have been set to music over the last century, and Joyce penned them with a tenor’s voice in mind.) Selected from the bulk of poems written during his Dublin days, Chamber Music depicts a love affair progressing from innocent beginnings to bitter dissolution. Like Shakespeare’s sonnets, the poems are vaguely autobiographical, with Nora Barnacle playing the role of the poet’s beloved.

Chamber Music represents Joyce at his most simplistic. Although the poems were collected in an Imagist anthology, they have little in common with the works of Ezra Pound or T.S. Eliot. Indeed, many of these poems are—dare I say it?—colored by the hues of the Celtic Twilight! Considering the amount of bile Joyce directed at this form of Irish romanticism, it’s shocking (and sometimes hilarious) to see Joyce invoking “invisible harps” and “wise choirs of faeries.” And utterly without irony!

Chamber Music begins with a pastoral prelude which invokes themes of enchantment, music, and love (Poems I-III). As the poet proceeds to woo his beloved, the poems occasionally shift into a faux-Elizabethan mode, like “merry airs” meant to be strummed on a lute. The most famous of these is “Poem V,” which has been set to music by everyone from Karol Szymanowski to Syd Barrett:

Poem V

Lean out of the window,

Goldenhair,

I hear you singing

A merry air.

My book was closed,

I read no more,

Watching the fire dance

On the floor.

I have left my book,

I have left my room,

For I heard you singing

Through the gloom.

Singing and singing

A merry air,

Lean out of the window,

Goldenhair.

After winning her affections in “Poem XI”—notable for the deployment of “snood,” “unzone,” and “maidenhood” in the same verse—we sense the Celtic Twilight descending as poet and lover wander across dark, starry lands and dewy gardens. Trouble rears its head when the poet’s jealous friend confounds their love throughout Poems XVII-XVII. (As usual with Joyce, the role of wicked friend is played Oliver St. John Gogarty, who’d later be fictionalized as Buck Mulligan in Ulysses.) A split occurs, and the young maiden is dishonored (“Poem XIX”). Undaunted, the poet declares his love above all else, which gives us stanzas such as these:

Poem XXII

Of that so sweet imprisonment

My soul, dearest, is fain—

Soft arms that woo me to relent

And woo me to detain.

Ah, could they ever hold me there

Gladly were I a prisoner!

Dearest, through interwoven arms

By love made tremulous,

That night allures me where alarms

Nowise may trouble us;

But sleep to dreamier sleep be wed

Where soul with soul lies prisoned.

Fain, woo, prisoned to be pronounced with two syllables; “Poem XXII” is a good example of why the poems in the first half of Chamber Music are a little hard to swallow—they’re puffed-up with shameless histrionics and bizarre affectations. There’s an ostentatiousness to Joyce’s word choices, especially when he smuggles in precocious words at the expense of the surrounding verses. Even overlooking the deliberate archaisms, words like “plenilune” and “Epithalamium” feel misguided, jarring the momentum of the poem and provoking a raised eyebrow. While such £10-words feel right when tumbled to the surface of Stephen Dedalus’ stream-of-consciousness meditations, here they stick out like jagged rocks troubling a garden path.

Nevertheless, all is not lost! As the poet’s feelings develop in complexity, Chamber Music shakes off its mantle of “welladay” theatrics. The poems improve as the poet’s relationship deteriorates—but then again, who wants to read poems about happy lovers? Eventually the poet is abandoned by his lover, and by “Poem XXVIII” things aren’t looking so good:

Sing about the long deep sleep

Of lovers that are dead, and how

In the grave all love shall sleep:

Love is aweary now.

“Poem XXX” declares the end of the affair, offering a genuinely striking line that plays on the previous poem: “We were grave lovers.” (It should be noted that here Chamber Music deviates from biography, as Nora remained with Joyce.)

The remaining poems find the poet alone, baring his broken heart to the unquiet sea. Chamber Music ends with “Poem XXXIV,” a remarkable piece that stands head-and-shoulders above everything preceding it. Finally slipping the chain that’s anchored him to the dead weight of antiquated form, Joyce produces a truly great poem, a cry of despair voiced as a Yeatsian vision of an onrushing army:

Poem XXXVI

I hear an army charging upon the land,

And the thunder of horses plunging, foam about their knees:

Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand,

Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the charioteers.

They cry unto the night their battle-name:

I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling laughter.

They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame,

Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil.

They come shaking in triumph their long, green hair:

They come out of the sea and run shouting by the shore.

My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair?

My love, my love, my love, why have you left me alone?

“Poem XXXVI” represents Joyce the poet at his best. It’s a shame we won’t see him again for another twenty years.

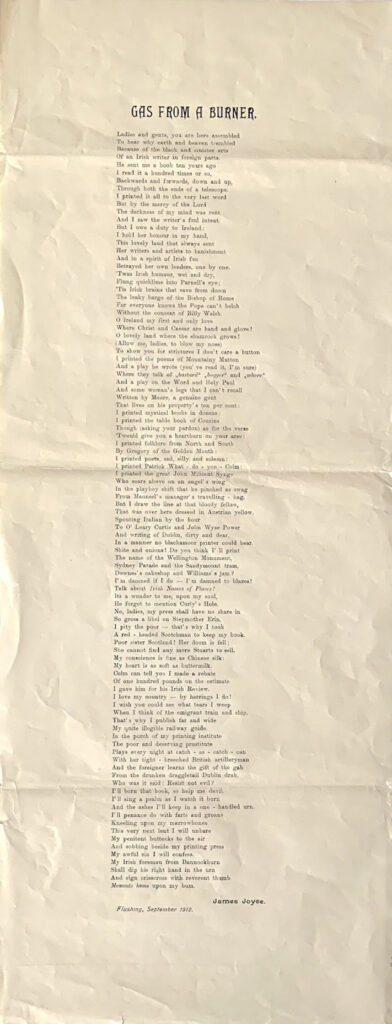

“Gas from a Burner”

“Gas from a Burner”

By James Joyce

Broadside, 1912

Available online at: Triolet Rare Books | Bonhams | Brazen Head

Written in a Dutch train station en route to Trieste, “Gas from a Burner” is a parting shot directed at Ireland and her hypocrisies. The principal subject of Joyce’s ire is the publishing industry. After several British publishers passed on Dubliners, including Grant Richards who agreed and then reneged, George Roberts of Maunsel & Company agreed to publish Joyce’s increasingly controversial book in Dublin. Soon Roberts himself became cagey, concerned about the stories’ “obscene” subject matter and “anti-Irish” character. After running off a thousand copies, the printer John Falconer supposedly smashed the type, and the pages were never bound. After two years of bitter argumentation between Joyce and Roberts, the copies were pulped, leaving Joyce in possession of the galley proofs. (Or that’s the story—there are certainly variations!)

“Gas from a Burner” is a no-holds-barred satire, a pompous declaration issued by a fictional publisher who personifies both Roberts and Falconer. The publisher considers it his sacred duty to protect Ireland from the “black and sinister arts” of James Joyce and the “gross libel” of his Dubliners. Not only does Joyce dress and speak like a foreigner, he has the unmitigated gall to reference actual Irish locations by name! In the end, the jingoistic publisher is proud to have burned the book:

I’ll burn that book, so help me devil.

I’ll sing a psalm as I watch it burn

And the ashes I’ll keep in a one-handled urn.

I’ll penance do with farts and groans

Kneeling upon my marrowbones.

This very next lent I will unbare

My penitent buttocks to the air

And sobbing beside my printing press

My awful sin I will confess.

My Irish foreman from Bannockburn

Shall dip his right hand in the urn

And sign crisscross with reverent thumb

Memento homo upon my bum.

In reality, the unbound copies weren’t actually burned; but the metaphor and its symbolic meaning were irresistible. It also allowed Joyce to engage in a multi-layered pun, with “Gas from a Burner” referring to the noisome “hot air” being vented by the book-burner, not to mention its flatulent source! Of course, Joyce’s satire had a broader target than just Roberts and Falconer, portraying their attitudes as symptoms of Ireland’s deeper problems: her subservience to the Catholic Church, her habit of betraying her leaders, and her need to banish her greatest writers and artists.

Joyce finished the satire on the train to Munich, then had it printed in Trieste. It was mailed to his brother for circulation in Dublin. If “The Holy Office” struck a match of anger, “Gas from a Burner” spread the flame, gleefully burning down bridges and ensuring Joyce would remain a literary exile. Indeed, it’s become mandatory to end this story with, “And Joyce never stepped foot in Ireland again!”

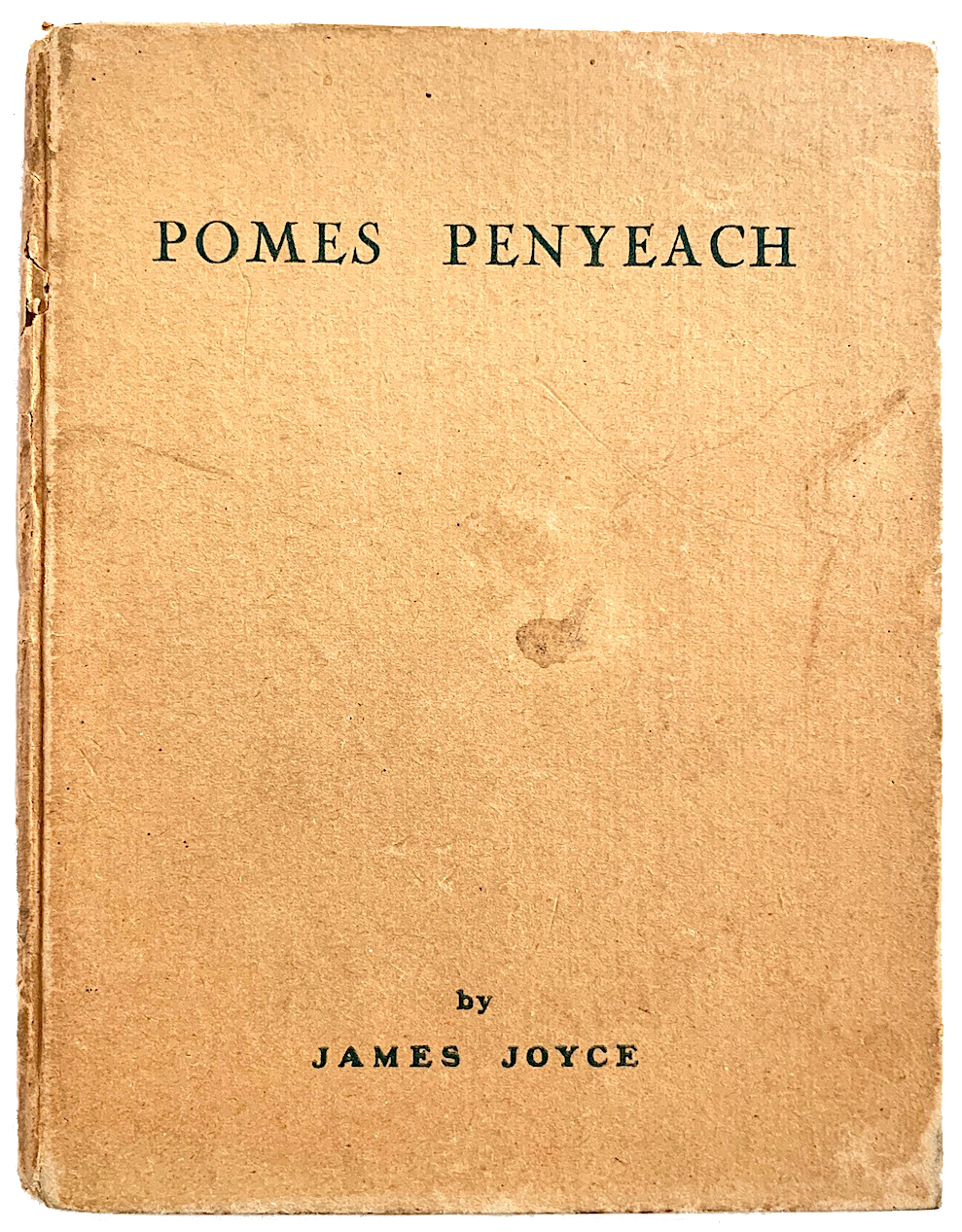

Pomes Penyeach

Pomes Penyeach

By James Joyce

Shakespeare & Company, 1927

Available online at: Internet Archive | JJA

Published in 1927, Pomes Penyeach is a collection of thirteen poems written while Joyce was working on Ulysses. The collection is named for its price—one shilling, or 12 pence—with a thirteenth “tilly” completing the baker’s dozen. As a whole, the collection reveals a more mature and cosmopolitan poet than Chamber Music. Now a middle-aged exile with a wife and daughter, Joyce uses these poems as a dark mirror to reflect the painful fragility of life. While poems like “She Weeps Over Rahoon” and “Simples” recall the lyrical simplicity of his earlier verse, they’re touched by a sense of poignancy and nostalgia absent from the theatrical Chamber Music. Joyce has also improved his craft, and Pomes Penyeach offers a broader variety of themes, structures, and styles.

This isn’t to say the poems are flawless. Joyce occasionally overreaches, and his considerable erudition remains his biggest obstacle to achieving clarity and grace. The poems are at their most awkward when struggling to constrain their protean language within shackles of traditional meter and form. It’s painful to see a verse soar to sublime heights, only to have its wings clipped by a clumsy rhyme: “A birdless heaven, seadusk, one lone star / Piercing the west, / As thou, fond heart, love’s time, so faint, so far, / Rememberest.” (“Tutto è sciolto”) The poems are at their best when their structures are more robust, capable of supporting Joyce’s extended metaphors and complicated webs of imagery. For instance, “Nightpiece” invokes a Catholic mass to describe the starry heavens:

Nightpiece

Gaunt in gloom,

The pale stars their torches,

Enshrouded, wave.

Ghostfires from heaven’s far verges faint illume,

Arches on soaring arches,

Night’s sindark nave.

Seraphim,

The lost hosts awaken

To service till

In moonless gloom each lapses muted, dim,

Raised when she has and shaken

Her thurible.

And long and loud,

To night’s nave upsoaring,

A starknell tolls

As the bleak incense surges, cloud on cloud,

Voidward from the adoring

Waste of souls.

It’s poems like these where the reader recognizes the author of Ulysses, and one longs for more freedom and experimentation. Indeed, the best poem in the collection is the one that comes closest to free verse: “A Memory of the Players in a Mirror at Midnight,” a surreal barrage that anticipates the intensity of Sylvia Plath:

A Memory of the Players in a Mirror at Midnight

They mouth love’s language. Gnash

The thirteen teeth

Your lean jaws grin with. Lash

Your itch and quailing, nude greed of the flesh.

Love’s breath in you is stale, worded or sung,

As sour as cat’s breath,

Harsh of tongue.

This grey that stares

Lies not, stark skin and bone.

Leave greasy lips their kissing. None

Will choose her what you see to mouth upon.

Dire hunger holds his hour.

Pluck forth your heart, saltblood, a fruit of tears:

Pluck and devour!

And who can resist a poem that uses the word, “quailing?”

Perhaps the greatest critic of Pomes Penyeach was Ezra Pound, who rejected them in 1926 with the remark, “they belong in the Bible or in the family album with the portraits.” Sylvia Beach thought differently, and the collection was published by Shakespeare & Company with a cover the color of an Irish Calville apple.

“Ecce Puer”

“Ecce Puer”

By James Joyce

The Criterion: A Quarterly Review. Faber & Faber, 1933

Available online at: Guardian “Poem of the Week”

Written in 1932, this poem was first published in The Criterion, Volume XII, Number XLVII. It also appeared in Joyce’s Collected Poems of 1936. Meaning “Behold the Boy-child,” “Ecce Puer” was written shortly after Joyce’s father died and his grandson Stephen was born. Returning to the unguarded simplicity of Chamber Music, “Ecce Puer” reveals a man in transition from being a son to becoming a grandfather, torn between “joy and grief” and finally realizing his need for reconciliation and forgiveness.

Ecce Puer

Of the dark past

A child is born;

With joy and grief

My heart is torn.

Calm in his cradle

The living lies.

May love and mercy

Unclose his eyes!

Young life is breathed

On the glass;

The world that was not

Comes to pass.

A child is sleeping:

An old man gone.

O, father forsaken,

Forgive your son!

Joyce’s Poetry: Collections

James Joyce: Poems and Shorter Writings

James Joyce: Poems and Shorter Writings

By James Joyce

Edited by Richard Ellmann, A. Walton Litz, and John Whittier-Ferguson

Faber and Faber, 1991

This wonderful volume collects all of Joyce’s published poetry, his 40 surviving “epiphanies,” his prose-poem Giacomo Joyce, and his 1904 essay “A Portrait of the Artist.”

Chamber Music and Other Poems

Chamber Music and Other Poems

By James Joyce. Edited by Sam Slote.

Alma Classics, 2017

This book is part of the Alma James Joyce series, connected with renowned Joycean Sam Slote. It contains all of Joyce’s published poetry: “The Holy Office,” Chamber Music, “Gas from a Burner,” Pomes Penyeach, and “Ecce Puer.” To these are added sixteen “uncollected” poems that appeared in various forms after Joyce’s death, from joking inscriptions written in friend’s books to mischievous limericks to translations of Horace and Verlaine. One of the most interesting—and certain objectionable, as it contains a now-unprintable pejorative—is “On Rudolf Goldschmidt” a song parody (to be sung to the tune of “The Amorous Goldfish”) written for one of Joyce’s Austrian friends in 1917. The last stanza anticipates the freewheeling tunes of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow:

CHORUS:

For he said it is bet—bet—better

To stick stamps on some God-damned letter

Than be shot in a trench

Amid shells and stench,

Jesus Gott, Donnerwet—wet—wetter.

The collection concludes with a biographical sketch by Sam Slote, notes on Joyce’s major works, and notes for many of the poems, including some pretty useful annotations for “Holy Office” and “Gas from a Burner!” If you’re only interested in a volume containing Joyce’s poetry, this is the one to get.

Joyce: Poems and a Play

Joyce: Poems and a Play

By James Joyce

Everyman’s Library, 2014

A slim and attractive hardcover, this book contains all of Joyce’s published poetry: “The Holy Office,” Chamber Music, “Gas from a Burner,” Pomes Penyeach, and “Ecce Puer.” It also features Joyce’s only surviving play, Exiles.

The Portable James Joyce

The Portable James Joyce

By James Joyce. Edited by Harry Levin.

First Edition: Viking Press, 1947

Current Revised Edition: Penguin, 1976

This trusty book contains the entire text of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Dubliners, along with excerpts from Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. More importantly, it contains all of Joyce’s published poetry: “The Holy Office,” Chamber Music, “Gas from a Burner,” Pomes Penyeach, and “Ecce Puer.” It also features Joyce’s only surviving play, Exiles.

Joyce Works:

[Main Page | Dubliners | A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man | Ulysses | Finnegans Wake | Poetry | Exiles | Other Works]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 20 June 2024

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com