Joyce Works: Other Works

- At July 17, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Youth has an end: the end is here. It will never be. You know that well. What then? Write it, damn you, write it! What else are you good for?

—James Joyce, “Giacomo Joyce”

This page collects some of James Joyce’s lesser-known works. They are listed in chronological order of writing, not publication.

Epiphanies (1901–1904, pub. 1965)

The Workshop of Daedalus: James Joyce and the Raw Materials for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Epiphanies by James Joyce

Edited by Robert Scholes and Richard M. Kain

Northwestern University Press, 1965

Available online at: Internet Archive | University of Wisconsin-Madison [PDF]

James Joyce: Poems and Shorter Writings

By James Joyce

Edited by Richard Ellmann, A. Walton Litz, and John Whittier-Ferguson

Faber and Faber, 1991

The Collected Epiphanies of James Joyce: A Critical Edition

By James Joyce

Edited by Sangram MacDuff, Angus McFadzean, and Morris Beja

University Press of Florida, 2024

In the manuscript of Stephen Hero Joyce describes an “epiphany” as “a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether in the vulgarity of speech or of gesture or in a memorable phase of the mind itself.” These “most delicate and evanescent of moments” offer elusive glimpses unto more profound truths.

Although the word itself has religious connotations, Joyce was interested in secularizing the term, redefining it as a more modest version of the revelations that mark Romantic literature. Between 1901 and 1904, Joyce recorded his “epiphanies” as they came to him, whether as overheard snippets of conversation, episodes from his life with family and friends, or somewhat enigmatic dreams. Such epiphanies ranged from quotidian observations of social deceptions to stark realizations about mortality. Their subjects included Joyce’s mother, his dying brother Georgie, the Sheehy family, Joyce’s early sweethearts, complete strangers, French prostitutes, and one famous barb at Oliver St. John Gogarty.

Joyce originally intended to publish his epiphanies as a “slim book.” Instead, they ended up as raw material for Stephen Hero; and once that draft was discarded, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Some epiphanies were eventually recycled into Ulysses and even Finnegans Wake. (Ulysses also features this self-deprecating glance over Stephen’s shoulder: “Remember your epiphanies written on green oval leaves, deeply deep, copies to be sent if you died to all the great libraries of the world, including Alexandria? Someone was to read them there after a few thousand years, a mahamanvantara.”)

Publishing History

Joyce is believed to have written at least 71 epiphanies, but only 40 have survived. They were never published in Joyce’s lifetime. In 1956, the University of Buffalo published the 22 epiphanies they had in their collection, recently purchased from Sylvia Beach. In 1965 Robert Scholes and Richard M. Kain combined these with the remaining 18 epiphanies held at Cornell, transcriptions made by Joyce’s brother Stanislaus. They arranged them in their best approximation of chronological order and published them in The Workshop of Daedalus, a critical history of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The epiphanies were finally made available to the wider reading public when Faber and Faber published Poems and Shorter Writing of James Joyce in 1991. Along with the 40 epiphanies, the book collected Joyce’s poetry, Giacomo Joyce, and his essay “A Portrait of the Artist.”

Collected Epiphanies of James Joyce

The most recent edition of Joyce’s epiphanies was published in 2024 by the University Press of Florida as Collected Epiphanies of James Joyce: A Critical Edition. Edited by Sangram MacDuff, Angus McFadzean, and Morris Beja, the book presents all Joyce’s epiphanies in newly-transcribed forms, complete with copious corrections, annotations, and critical notes. Rejecting Scholes and Kain’s system of organization, the editors arranged them in the order they appear in the original manuscripts. They also rejected the previous convention of designating the epiphanies by number, replacing the generic numbers with descriptive titles devised by Morris Beja. (These titles are placed in brackets to mark them as editorial conveniences rather than authorial appellations.)

The book begins with a lengthy essay about the history of the epiphanies, their critical reception, and their relationship to the Joyce canon. Written in a readable style with a minimum of academic jargon, the essay explains what the editors hope to achieve: to restore the epiphanies to wider circulation, place them in a broader critical context, and trace their “appearances and echoes” throughout Joyce’s mature work.

This informative introduction is followed by the 40 epiphanies—the reason most non-academics will likely purchase this collection. Each epiphany occupies its own page and is mercifully free of footnotes. A single endnote at the bottom of the page directs the reader to “notes and commentary.”

As the editors discuss in their introduction, Joyce’s epiphanies are loosely divided into two types. The first read like fragments from a play, complete with speakers and stage directions. These scenes are ostensibly recorded from Joyce’s real-life observations of friends, family, and strangers. For the most part these epiphanies are subtle, even low-key; snapshots of moments taken during everyday conversation. But a closer look reveals that each “snapshot” exposes something more profound about the interaction—a subtle realignment of interpersonal dynamics, a defining moment of character, a “vulgarity of speech” that unmasks a true opinion. For instance, “The Priest That Writes Poetry” records a conversation between Joyce and John O’Mahony, a local lawyer and journalist:

[Dublin: in the Stag’s Head,

Dame Lane]

O’Mahony—Haven’t you that little priest that

writes poetry over there—Fr Russell?

Joyce—O, yes…I hear he has written verses.

O’Mahony—(smiling adroitly)…Verses, yes…that’s

the proper name for them…*

On the surface this seems like a fairly banal exchange. But through Joyce’s deft framing, we see the precise moment where Joyce’s youthful pretention is bruised by O’Mahony’s airy condescension—the lawyer’s use of “little” and “proper;” Joyce’s hesitation between his initial enthusiasm and his awkward—or is it ironic?—reformulation.

It’s easy to see how such epiphanies were absorbed into the dialogue of Stephen Hero and Portrait. On the other hand, a few of these real-life epiphanies transcend “vulgarities in speech or of gesture” to illuminate something considerably more complex and meaningful. Of these, the most famous is probably “The Hole in Georgie’s Stomach.” The epiphany was written about Joyce’s younger brother, who’d soon be dead from peritonitis.

[Dublin: in the house in Glengariff Parade: evening]

Mrs Joyce—(crimson, trembling, appears at the parlour door) … Jim!

Joyce—(at the piano) … Yes?

Mrs Joyce—Do you know anything about the

body?.. What ought I do? … There’s

some matter coming away from the hole in Georgie’s stomach ….

Did you ever hear of that happening?

Joyce—(surprised)… I don’t know ….

Mrs Joyce—Ought I send for the doctor, do you

think?

Joyce—I don’t know…… What hole?

Mrs Joyce—(impatient) … The hole we all have

…. here (points)

Joyce—(stands up)

While a version of this incident is familiar to readers of Stephen Hero, it’s quite different to encounter this scene as an actual occurrence in the Joyce household than a misfortune projected onto some fictional sister. The combination of panic, bafflement, and comedy—along with the image of some form of matter creeping from a child’s navel—strikes several disparate notes at once, an uneasy chord that refuses to resolve harmoniously. But then again, that’s the point, and the best of these epiphanies conjure a sense of discomfiture or unsettlement.

The second type of epiphany takes the form of prose-poems such as “An Arctic Beast” and “The Big Dog.” These are narratives drawn from Joyce’s dreams; although some might be daydreams or embellished impressions. Many of these “dreams” were later recycled as material for Portrait and Ulysses. For instance, the ghost of Joyce’s mother that haunts Ulysses has its first manifestation in “She Comes at Night”:

She comes at night when the city is still;

invisible, inaudible, all unsummoned. She

comes from her ancient seat to visit the

least of her children, mother most venerable,

as though he had never been alien to her.

She knows the inmost heart; therefore

she is gentle, nothing exacting; saying,

I am susceptible of change, an imaginative

influence in the hearts of my children.

Who has pity for you when you are sad

among the strangers? Years and years I

loved you when you lay in my womb.

These dream-epiphanies possess a poetic force lacking in Joyce’s contemporary poetry, and many of the pieces in Chamber Music pale in comparison to epiphanies like “She Comes at Night” or “Half-Men, Half-Goats.” (Although “Hoofs Upon the Dublin Road” calls to mind “I Hear an Army,” and both carry strong echoes of Yeats.)

The final section of Collected Epiphanies contains detailed notes for each epiphany. It’s here where the book earns its “critical edition” subtitle. The editors discuss each epiphany’s origin and real-life referents, offer possible meanings and interpretations, amplify or refute previous critical commentary, highlight any textual variations between the various manuscripts, and trace each epiphany’s “echoes and adaptations” in Joyce’s later works. The section includes extensive quotations from Stephen Hero, Portrait, Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake. Best taken a few epiphanies at a time, these notes offer an invaluable window into Joyce’s creative process. In their introduction to the book, the editors claim that Joyce’s epiphanies represent an important wellspring for his later work, and that Joyce returned to these “most delicate and evanescent of moments” throughout his entire career. By the time the final page is turned, it seems churlish to refute this claim.

In the end, Collected Epiphanies of James Joyce strikes an excellent balance between the academic reader and the independent Joycean. Those just interested the epiphanies will find them handsomely presented, while the additional critical material places them nicely in context—and as I’ve mentioned, the editors strive for transparency and readability. Aside from wishing the “Table of Epiphanies” was placed at the front of the book, the only quibble here is the price. While Collected Epiphanies is not as ludicrously overpriced as most academic books, casual readers may hesitate before paying $30 for a 200-page paperback. (Though it’s still less expensive than used copies of Workshop of Daedalus or Poems and Shorter Writings.) Its inflated price aside, Collected Epiphanies is an excellent book, and one that deserves a place on any serious Joyce shelf.

*Wordpress makes it impossible to duplicate the idiosyncratic typesetting of the epiphanies.

Before Sunrise (Translation 1901, pub. 1978)

Before Sunrise (Translation)

By Gerhardt Hauptman.

Translation by James Joyce. Edited by Jill Perkins.

Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, 1978

Available online at: Internet Archive

One of Joyce’s earliest works was a translation of Vor Sonnenaufgang, an Ibsenesque drama by German playwright and Nobel laureate Gerhardt Hauptmann. Created in the summer of 1901, the manuscript was Joyce’s attempt to bring this play to an English-speaking audience. In 1978 the manuscript was published by the Huntington Library and Art Gallery, a handsome hardcover featuring an introduction, notes on provenance, critical commentary, and an essay called “Joyce and European Drama, 1900-1906.” Jill Perkins describes the manuscript in her preface:

It came to me as part of a collection of Joyce manuscripts and first editions from my father, John Hinsdale Thompson, in 1970. Knowing that Joyce’s place in twentieth-century literature was secure enough to prevail against what Ezra Pound called his “juvenile indiscretion,” we agreed that an eventual edition of the translation was justified for its interest to scholars who heretofore have had no first-hand knowledge of what Joyce did with the drama in his unsuccessful attempt to provide a modern Continental play for the Irish Literary Theatre. Vor Sonnenaufgang (1889) had not been published in an English edition by 1901, so Joyce’s “Before Sunrise” was, in effect, the first English translation of Hauptmann’s play. I considered myself only a temporary custodian of the manuscript and, in 1974, disposed of the entire collection in the interest of its security, preservation, and availability to scholars.

It should be noted that the printed text of the play is faithful to the holograph manuscript, short of being a facsimile reproduction. There are no silent emendations in the text itself: all errors and omissions are retained and corrections appear in the notes following Joyce’s translation.

Back in 1997 or so, an anonymous visitor sent me this short commentary, which I reprint because it still makes me laugh:

Much of the interest lies in the numerous missteps and mistakes the young Joyce, new to the German language, makes. Joyce, the story goes, was annoyed that this manuscript ever made it out of his hands, so buying this book is a little like printing up pre-Nine Stories Salinger stories from Saturday Evening Post microfilm. Personally, I think Stephen’s unholy mania for biography-based criticism—of the shady figure of Shakespeare, no less—warrants a reading of this play!

On Ibsen (1901–1906, pub. 1998)

On Ibsen

By James Joyce. Edited by Dennis Philips.

Green Integer, 1998

James Joyce was an early and enthusiastic supporter of Henrik Ibsen, the “father of realism” whose controversial plays had shocked the late Victorian world with their frank depictions of sexuality, infidelity, and bourgeois hypocrisy. In April 1900, an eighteen-year old “James A. Joyce” published a glowing review of Ibsen’s When We Dead Awaken in the Fortnightly Review. Ibsen responded with a generous letter; as Joycean biographer Edna O’Brien writes, “for Joyce this commendation was a transfiguration, the moment when he ceased to be an Irishman and became a European.” Joyce responded in kind with a letter of his own: “Dear Sir, I wish to thank you for your kindness in writing to me. I am a young Irishman, eighteen years old, and the words of Ibsen I shall keep in my heart all my life.” Ibsen would continue to influence Joyce over the following years. Joyce began to study Danish, and Ibsen’s name is mentioned in Stephen Hero over twenty times! Joyce wrote two plays of his own, both strongly influenced by Ibsen. The first was entitled A Brilliant Career, and was modestly inscribed to the artist’s “own soul.” Written in 1900, the five-act play was sent to the theatre critic William Archer, Ibsen’s biggest advocate in the UK, responsible for translating many of his plays into English. According to Joyce’s brother Stanislaus, Joyce himself destroyed the play. Now considered a “lost work,” its existence has been forgotten by everyone but Joyce scholars. The second was Exiles.

This slim book collects four of Joyce’s published pieces on Henrik Ibsen, including his essays of 1900 and 1903. It contains an introduction by Dennis Philips examining Joyce and his changing relationship to Ibsen.

Stephen Hero (1901–1906, pub. 1944)

Stephen Hero By James Joyce Jonathan Cape, 1944 |

Stephen Hero By James Joyce New Directions, 1963 |

Probably composed between 1901 and 1906, Stephen Hero is an early draft of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The book is incomplete. According to Joycean legend, after the manuscript was rejected by twenty publishers on the grounds of indecency, Joyce flung it in the fire, leaving Nora to salvage the remains. Of course, the fact no surviving pages show any damage, not to mention the emergence of new pages years later, suggests this story is apocryphal.

The novel follows the adventures of Stephen Dedalus, the name Joyce would later use to represent himself in Portrait and, somewhat more mockingly, Ulysses. As young Stephen struggles to assert his identity as an artist, he rebels against his family, his country, and his church. Stephen Hero contains much of the same material found in Portrait, but it’s narrated in more conventional prose and features a great deal of dialogue. While Stephen Hero may lack the spark of creative genius that illuminates Portrait, it offers an intimate window into Joyce’s early life.

Giacomo Joyce (1912–1914; pub. 1968)

Giacomo Joyce By James Joyce Introduction by Richard Ellmann Faber and Faber, 1968 |

James Joyce: Poems and Shorter Writings By James Joyce Edited by Richard Ellmann, et. al. Faber and Faber, 1991 |

Giacomo Joyce By James Joyce Introduction by Colm Tóibín Faber and Faber, 2019 |

A short work composed in Trieste sometime between 1912-1914, Giacomo Joyce is a prose-poem about an infatuation Joyce had with one of his English students, an olive-skinned, dark-haired Jewish woman. (As Richard Ellman states, Giacomo Joyce “is Joyce’s attempt at the sentimental education of a dark lady.”) Composed of twelve hand-written pages, the manuscript has been called everything from “fictionalized diary entries” to a “novelette,” and consists of fifty prose fragments separated by varying amounts of white space. These fragments vary wildly—some read like diary entries, others are interior monologues that prefigure Ulysses, while a few consist of single sentences. While the identity of Joyce’s crush remains the subject of critical debate, the work is surprisingly personal, written from the first-person perspective and referring to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Nora, and Joyce’s real-life friends. The lady herself is unnamed.

In his great biography James Joyce, Richard Ellmann identified the “dark lady” as Amelia Popper, but that theory has since been thoroughly dismantled by the Italian writer Helen Barolini. Today, most Joyce scholars believe the subject of Giacomo Joyce is a fictional composite of several women, including Amelia Popper, Annie Schleimer, and Emma Cuzzi. Whether or not Giacomo Joyce is predominately factual or fanciful, the manuscript was never typeset or published, and Joyce cannibalized it for various scenes in Portrait, Exiles, and Ulysses.

The manuscript eventually fell into the hands of Joyce’s brother Stanislaus, who sold it to an anonymous collector. This collector shared the manuscript with Richard Ellmann, who published much of Giacomo Joyce in his biography in 1959. In 1967 the complete text was published by Faber and Faber, along with an informative introduction and notes by Ellmann.

The Cat and the Devil (1936, pub. 1964)

The Cat and the Devil

By James Joyce

Illustrated by Richard Erdoes

Dodd, Mead & Company, 1964

Available online at: Internet Archive

In August of 1936, James Joyce wrote a letter to his grandson Stephen, and in that letter he told an amusing story about a French town that needed a bridge. The devil agrees to build a lovely stone bridge, but the first soul to cross it would be condemned to the devil’s keeping. The mayor tricks the devil by shooing a cat across the bridge. The devil adopts the cat, but curses the town. It’s a charming tale, but the postscript is where we see Joyce the most clearly:

P.S. The devil mostly speaks a language of his own called Bellsybabble which he makes up himself as he goes along but when he is very angry he can speak quite bad French very well though some who have heard him say that he has a strong Dublin accent.

In 1964 the story was extracted from Joyce’s letters and published as a children’s book with illustrations by Richard Erdoes. Since then, there have been other versions illustrated by Gerald Rose, Roger Blachon, and Marcello Lelis. There’s also a Portuguese translation illustrated by Bill Borges, and a Chinese edition. The Gerald Rose version is difficult to acquire, but the indomitable Maria Popova features some of his fanciful illustrations on her wonderful blog.

The Cats of Copenhagen (1936, pub. 2012)

The Cats of Copenhagen

By James Joyce

Illustrated by Casey Sorrow

Scribner, 2012

Another story about cats pulled from Joyce’s letters to his grandson Stephen.

Publisher’s Description: The Cats of Copenhagen was first written for James Joyce’s most beloved audience, his only grandson, Stephen James Joyce, and sent in a letter dated September 5, 1936. Cats were clearly a common currency between Joyce and his grandson. In early August 1936, Joyce sent Stephen “a little cat filled with sweets”—a kind of Trojan cat meant to outwit grown-ups. A few weeks later, Joyce penned a letter from Copenhagen that begins “Alas! I cannot send you a Copenhagen cat because there are no cats in Copenhagen.” The letter reveals the modernist master at his most playful, yet Joyce’s Copenhagen has a keen, anti-authoritarian quality that transcends the mere whimsy of a children’s story. Only recently rediscovered, this marks the inaugural U.S. publication of The Cats of Copenhagen, a treasure for readers of all ages. A rare addition to Joyce’s known body of work, it is a joy to see this exquisite story in print at last.

Collections

James Joyce: Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing

James Joyce: Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing

By James Joyce. Edited by Kevin Barry.

Oxford University Press, 2000

Available online at: Internet Archive

This book is a collection of critical writings, reviews, lectures, and letters of protest. Some of the more noteworthy pieces include literary criticism about James Clarence Mangan, Henrik Ibsen, and William Blake, musings on Home Rule, and even a bullockbefriending piece called “Politics and Cattle Disease.” Joyce was no Borges—he was only a second-rate critic, and his nonfiction rarely approaches the luminosity of his prose—but the collection offers a glimpse into the man behind the fiction, the fellow off “paring his fingernails.” A curious reader may also find traces of Joyce’s stylistic and aesthetic development; for instance, his passionate defense of Irish-French tenor John Sullivan reflects the revolutionary prose of Finnegans Wake.

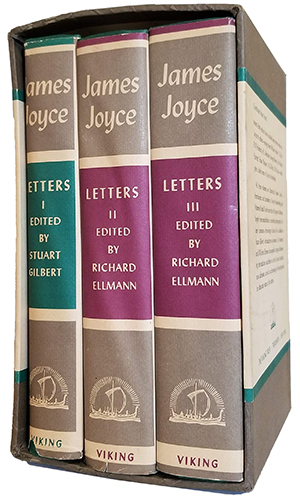

Letters of James Joyce, Vol. I, II, & III

Letters of James Joyce, Vol. I, II, & III

By James Joyce. Edited by Stuart Gilbert & Richard Ellmann

Faber and Faber/Viking, 1957-1966

Available online at Internet Archive: Vol I, Vol III

In 1957 Faber and Faber/Viking published Letters of James Joyce, a selection of Joyce’s correspondences edited by Stuart Gilbert and introduced by Richard Ellmann. It began with Joyce’s famous teenage letter to Henrik Ibsen and concluded with a letter dated 20 December 1940 to the Mayor of Zurich. In 1966, Volumes II and III were published simultaneously, edited by Richard Ellmann: “Since Stuart Gilbert edited Letters of James Joyce in 1957 many new letters have been found. The two present volumes, numbered II and III, include 1136 letters from Joyce, and 197 letters from other persons.” Viking released the trio as a box set that same year:

These three volumes, containing more than 1500 letters, comprise Joyce’s collected correspondence. The initial selection, from the letters that were available sixteen years after Joyce’s death, was made by his long-time friend and explicator, Stuart Gilbert, and is now reissued with corrections as Volume I of this set. It is particularly value for its many letters from Joyce’s Paris years, 1920 to 1939. Volumes II and III, edited by Richard Ellmann, Joyce’s biographer, are from the much larger number of letters now available. Their total of about 1100 includes 200, chiefly from Joyce’s earlier years, to his father, mother, and brother, and some 60 revelatory letters to his wife. Together, the volumes display in great variety Joyce’s courage and plaintive yet almost ruthless confidence, and his cool persistence, during years of hand-to-mouth exile on the Continent, in altering the direction of literature in English.

For explanatory value, as well as for their intrinsic interest, both editors have included some letters written to Joyce by others—among them William Archer, T.S. Eliot, B.W. Huebsch, H.L. Mencken, George Moore, Ezra Pound, Harriet Shaw Weaver, H.G. Wells, W.B. Yeats—which give a fuller sense of Joyce’s friendships.

All three volumes are illustrated, Volume I with a frontispiece and facsimiles off Joyce’s handwriting, and Volumes II and III with more than fifty pages of halftones, largely from unpublished or unfamiliar photographs. Value I contains a chronology of Joyce’s life in addition to Stuart Gilbert’s introduction and memoir. For Volumes II and III Richard Ellmann has supplied a long and illuminating introduction, and there is a list of Joyce’s multitudinous addresses, as well as a chronology of his writings and an elaborate index of the letters.

Although the set no longer contains Joyce’s “collected” correspondence—the appearance of new literary letters is always an inevitability, as any H.P. Lovecraft fan will attest!— it’s still an impressive achievement, and showcases Ellmann’s characteristically obsessive approach to Joyce biography and scholarship.

Selected Joyce Letters

Selected Joyce Letters

By James Joyce. Edited by Richard Ellmann

Faber and Faber/Viking, 1975

Selected Joyce Letters was originally intended as a “short and convenient selection” of letters sampled from the three volumes of Letters of James Joyce. Even as the project was underway, new correspondence came to light, including some interesting letters between Joyce and Harriet Shaw Weaver. More importantly, restrictions on certain letters were dissolved, allowing Ellmann to fully print the “extraordinary intimate” letters Joyce wrote to Nora in the winter of 1909. Although Ellmann had a “Volume IV” in the back of his mind, these new letters were included in Selected Joyce Letters. Published in 1975, the “short and convenient selection” clocked in at 400+ pages, with the new material ensuring interest even for collectors who already possessed the box set. And this “interest” was not for the Weaver letters, that’s for sure! Selected Joyce Letters is notorious for its inclusion of Joyce’s “smutty” letters to Nora, which start poetic and coy, but end up as full-blown pornography. While modesty forbids me to offer quotations, other Web sites are a little more NSFW!

Joyce Works:

[Main Page | Dubliners | A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man | Ulysses | Finnegans Wake | Poetry | Exiles | Other Works]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 18 September 2024

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com