Joyce Works: “Finnegans Wake”

- At June 01, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

If our society should go to smash tomorrow (which, as Joyce implies, it may) one could find all the pieces, together with the forces that broke them, in “Finnegans Wake.” The book is a kind of terminal moraine in which lie buried all the myths, programmes, slogans, hopes, prayers, tools, educational theories, and theological bric-a-brac of the past millennium. And here, too, we will find the love that reanimates this debris . . . Through notes that finally become tuneable to our ears, we hear James Joyce uttering his resilient, all-enjoying, all-animating ‘Yes’, the Yes of things to come, a Yes from beyond every zone of disillusionment, such as few have had the heart to utter.

—Joseph Campbell

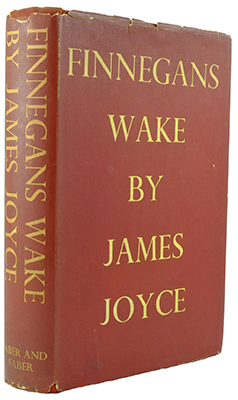

Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake

By James Joyce

Faber and Faber, 1939

After Ulysses, Joyce spent the remainder of his life working on his final masterpiece, a book he kept veiled in secrecy, referring to it as “Work in Progress.” As the years wore on, periodic installments were published in literary magazines, and the pages both excited and alarmed his friends and supporters. Something very weird was going with Joyce, and it was clear that his next book would be as different from Ulysses as that epic novel was from Portrait.

In that, at least, they were not disappointed! Purely in terms of literary technique, Finnegans Wake is probably the most astonishing—and controversial—book ever written. Published in 1939 after seventeen years of labor, it was received with a wide range of responses: curiosity, bafflement, delight, irritation, even open hostility. Some critics dismissed it as a waste of paper, a tangled web of gibberish without plot, without content, and without meaning. More than a few questioned Joyce’s sanity!

And yet, whole careers have been dedicated to studying Finnegans Wake, and its enthusiasts past and present approach the book with something akin to awe. Fans of the Wake have called it a peerless masterpiece, a cultural artifact, a literary miracle, a cosmic joke; it’s even been referred to as a quasi-sentient artificial intelligence. There’s a mystical quality to Finnegans Wake that remains suspended between the sublimity of poetry and the mystery of religion; quotations from the book are even cited in a Biblical fashion.

So, then—what’s the big deal?

Well, glad you asked. But, describing Finnegans Wake is a difficult assignment. It’s best to approach understanding in stages, in spirals, each pass revealing more of what’s really going on. After several stalled attempts, I finally settled on a question-and-answer format, a friendly exchange between myself and a potential first-time reader. Kind of a FAQ file, if you will. (Finnegans Ache Quailified?) After laying a little groundwork, I’ll describe the unique narrative and language of Finnegans Wake, then I’ll attempt to summarize its “plot” and structure. While this might seem a touch backwards, bear with me. I guarantee that by the end, you’ll either rush out to buy the book, or you’ll be hiding under your bed clutching a bottle of aspirin.

sentenced to be nuzzled over a full trillion times for ever and a night till his noodle sink or swim by that ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia

—FW 120.12-14.

Finnegans Wake is difficult. So is Ulysses. What, it’s just another tricky novel to read?

Finnegans Wake is certainly difficult; but it’s a different kind of “difficult” than novels like Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Gravity’s Rainbow, The Recognitions, or Infinite Jest. Even assigning Finnegans Wake to a genre is tricky—it’s a work that willfully confounds categorization. While most refer to it as a novel, it’s certainly like no other novel; only Beckett’s The Unnamable comes close. Others consider the Wake a form of poetry, but that’s also unsatisfying. It’s been called an epic, a myth, a riddle, a puzzle, and a philosophical text. The prominent Joyce scholar Derek Attridge affectionately called it “an unassimilable freak.” At the end of the day, Finnegans Wake stands alone, sui generis, a unique creation in the world of literature that marks a turning point between High Modernism and postmodernism.

OK, it’s unique, I get it. So what’s it about?

The usual short answer is: If Ulysses is about a day, Finnegans Wake is about a night. But this is misleadingly simplistic. Although the narrative of Ulysses plays tricks at times, the story of Stephen, Bloom and Molly remains consistent. Despite a few distortions and hallucinations, their day is easy to understand: the characters wake up, go about their business, and go to bed. To say that Finnegans Wake is “about a night” is not to imply this same continuity—this isn’t a book that takes 628 pages to describe a sleeping family in Dublin!

But before I continue, a brief word; because on a superficial level, the book is about a sleeping family in Dublin: an amiable but curiously guilty husband, his forgiving wife, their two competitive sons, and their lovely daughter. But the narrative doesn’t concern itself with their tossing and turning and snoring. During the course of the night, the father dreams, and Finnegans Wake is the text of this dream. And not just any dream. His dreams have dreams of their own, and these dreams encompass the whole of history with its myriad races, religions, mythologies, and languages; its loves and hates, enmities and affinities—all melting and flowing into each other, revealing the cyclical, unchanging nature of life.

Does this mean that Finnegans Wake is essentially a book about a long dream?

Not exactly. Finnegans Wake doesn’t describe a dream; the text is a dream. Or at least, it comes as close as Joyce could to imitating a dream.

“One great part of every human existence is passed in a state which cannot be rendered sensible by the use of wideawake language, cutanddry grammar and goahead plot.”

—James Joyce on “Finnegans Wake”

How does he do that?

In Finnegans Wake, Joyce takes “stream-of-consciousness” writing to the next level, plunging the reader into another world, one where the narrative conventions of the waking world are abolished. In dreams, different rules congeal from the fog, and since analysis is a tool of the waking mind, we’re not granted immediate comprehension of these rules—that is, assuming they can even be understood. In dreams, it’s unremarkable when a strange woman we’re talking to suddenly becomes our mother, or a house we’ve never seen rings with the familiarity of home, and then becomes a castle; or a tree becomes a stone. The mercurial narrative of Finnegans Wake reflects this hypnogogic reality. Characters and scenes melt into each other—sometimes literally!—and allegorical or mythic counterparts exist for everything and everybody. Time collapses and becomes meaningless. Identities are mutable, a series of masks to be shuffled and discarded. In the Wake, even words themselves resist definition.

So characters and places switch around. I’ve seen Mulholland Drive, I can handle that. Is that the only way the Wake (see, I said “the Wake,” eh?) reflects the dreamworld?

Again, not exactly. Even though it embraces the bizarre “logic” of dreams, Finnegans Wake is more than a perplexing book filled with mysterious disconnections and paradoxes. It goes much further than a David Lynch film, or even the “Circe” and “Penelope” episodes of Ulysses, which certainly have dreamlike qualities. In Finnegans Wake, Joyce wanted to do something more extraordinary: he wanted to create a new language, one that reflects the elusive workings of the subconscious mind.

To accomplish this, Joyce spent seventeen years creating a kind of dreamspeak, a language that’s basically English, but extremely malleable and all-inclusive, a fusion of portmanteau words, stylistic parodies, and complex puns. And by this, I don’t mean a bunch of neologisms and puns scattered throughout a narrative stream; the whole book is related in this language. And it goes much deeper than puns and parodies. Like tributaries flowing into a collective sea, dozens of other languages merge into the “English” narrative, forever changing its basic character.

To pivot metaphors, Joyce uses the Wake as a semantic reactor vessel, smashing words into their fundamental atoms and rearranging them into fresh linguistic molecules. Like energetic particles, some words vibrate on several levels at once, charging each sentence with multiple valences of meaning. Some words exert a strange attraction over their neighbors, so one suggestive noun or verb colors an entire sentence with shades of nuance, ripples in a chain reaction of associations—

Whoah there, Mr. Wizard! How about an example?

Sorry, I love a good extended metaphor. OK, take this famous passage, one of many wherein the Wake refers to itself:

in the Nichtian glossery which purveys aprioric roots for aposteriorious tongues this is nat language in any sinse of the world

—FW 83.10-12

“Nicthian” is a pun that resonates on several levels. First, it suggests Nicht, German for “nothing;” as well as the related German word nichtig, or “futile.” It also evokes several related words for “night,” from the English “night” to the German Nacht to the Latin noctis. Additionally, it calls to mind the term “Nietzschean.” “Glossery” mimics the noun “glossary,” but the “e” gives it the feel of a verb, perhaps implying “the act of glossing over.” “Aprioric” ironically combines “a priori” with “aporia”—an assumed precondition merged with a negating paradox. Along with the philosophical compound “aposteriorious,” it strengthens the overtones of Nietzschean philosophy while adding a bit of levity with “posterior tongues.” Nat is Danish for “night,” but it also sounds like English for “not,” especially in light of the possible sentence “not language in any sense of the word.” But of course, what we’re really given is “sinse of the world,” surely familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of Christian theology.

Although you may disagree with some of these interpretations, my point is hopefully clear: the overdetermined sentences of Finnegans Wake shimmer with multiple meanings, some even contradictory. Even when analyzed, an exact meaning is impossible to pin down—or at least to the waking mind, which demands rapid comprehension based on a rigid system of syntax. The “Nichtian” sentences keep slipping free, melting back into the dream, leaving a set of impressions in their wake.

How does one best approach this type of Joycean “nat language?”

It’s probably obvious by now that Finnegans Wake can’t be read like a normal book. If you’re expecting to make immediate sense of the narrative, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment and frustration. It’s best to approach the Wake with a relaxed mind, receptive to the sudden metamorphoses and logical slippages common to dreaming. Think about those fleeting moments before sleep—the hypnogogic state where images flow through your mind, relaxing and delicate, full of hieratic meaning—a “sense” that quickly dissolves upon waking.

I keep hearing people claim that Finnegans Wake is “funny.” Is that because of the puns?

Partly, yes—but it goes deeper than that. Like dreams, humor offers another key to unlocking the Wake. After all, puns and jokes often rely on sudden disruptions of order, surprising double-entendres, and unexpected meanings. You don’t “get” a joke using logic and reason—nothing kills a joke faster than explaining it to an HR person! Like many forms of humor, the “nat language” of Finnegans Wake operates best at the margins of consciousness, comfortably removed from the “harsh light of reason” or the “cold light of logic.” Even these phrases are telling: rationality is associated with daylight and derangement with night. There’s a reason Joyce scholar John Bishop called his wonderful analysis of Finnegans Wake “Joyce’s Book of the Dark.”

So there’s no sense at all? It’s “Abandon hope all ye who enter here?”

Not at all. Dreams, puns, and jokes may help us understand the Wake, but it’s important to remember that Finnegans Wake is the creation of a rational, waking mind, and has been carefully planned out. Nor has Joyce abandoned grammar entirely. Because the Wake’s “nat language” is based on English, its syntax remains familiar and comprehensible. Like approaching a new vocabulary word, a confused reader may rely on his old friend “context.”

Lewis Carroll’s poem “Jabberwocky” is a common comparison to make when discussing the Wake. For instance, you’re probably familiar with its opening stanza:

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

We have no idea what this means; except, we kinda know what it means!

Upon reflection, one finds that Joyce’s language does make sense; but a different kind of sense, a playful sense that’s tricky to explain. And that’s the best way to “understand” the Wake—just let it play. When understanding comes—and sometimes that’s sentence by sentence, not page by page!—you feel a frisson of joy ripple through your brain. (If you’re familiar with Roland Barthes, his idea of jouissance comes to mind.) I realize I’m about to sound like a cultist, but Finnegans Wake is located near the primal stratum of the collective unconscious, where

countlessness of livestories have netherfallen by this plage, flick as flowflakes, litters from aloft, like a waast wizzard all of whirlworlds.

—FW 17.26-29

Yes, you do in fact sound like a cultist. So what about a plot? Is there even a plot at all?

Yes and no. While there’s never anything as straightforward as a traditional plot, there’s a set of recurring characters, associations, and events that loosely organize the narrative. The complexity arises from the fact that there are several layers to these characters, associations, and events. Like the convoluted puns Joyce uses to carry his story, the world of the novel contains multiple dimensions. Finnegans Wake is like a mathematical fractal: each iteration exposes a deeper universe of meaning, yet remains remarkably self-contained and self-generating.

With this fractal metaphor in mind, I’ll take the “plot” through a few iterations. Caveat lector: The following layers are not meant to mirror chronological plot development. The replicating associations take place throughout the book, and every “character” has episodes during which they are the central focus. Cool?

The first layer of plot is the most simple, and may be taken as the “waking world.” Let’s return the aforementioned family. Our principal cast seems to be one Mr. Porter, his wife Ann, their daughter Isabel, and their two sons, Kevin and Jerry. Mr. Porter is dreaming at night, and throughout the book we hear the tap-tap-tapping of a branch at his window. But Finnegans Wake does not concern itself with the waking world, so the Porters can hardly be called its protagonists. Besides groggily checking on his sons upstairs and (maybe?) making sleepy love to his wife, we don’t hear much from Mr. Porter.

Wait a moment. You said, “seems to be” Mr. Porter.

Er…yeah. By taking the Porter route, I’m expressing my own bias in the ongoing debate concerning which “character,” if any, is actually dreaming the text. Unsurprisingly, Joyce never makes it clear. There’s plenty of textual evidence to support the Mr. Porter interpretation, although some Wakeans have alternate theories. Some think that Mr. Porter is just another dream projection; possibly of James Joyce himself. Others feel H.C. Earwicker is the central character—more on him in a bit. Then there’s some who believe that Finnegans Wake is Leopold Bloom’s dream, and may be a sequel to Ulysses, taking place the morning of June 17, 1904. Joyce himself suggested the dreamer was an old man dying by the Liffey. Most critics reject his suggestion, finding it an explanation for certain sequences in the Wake, but not the origin of the Wake.

So back to the fractal…?

Let’s move to the second layer. Here, Mr. Porter’s dreaming mind has recast his family into less mundane identities. Mr. Porter becomes Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, and his wife becomes Anna Livia Plurabelle. Earwicker apparently owns a tavern in Chapelizod, an area of Dublin, and has a prominent profile in the community despite coming from Scandinavian stock. (Which makes him something of an outsider, similar to Leopold Bloom.)

Two indistinct sins weigh upon Earwicker’s conscience. The first concerns an episode that took place in Phoenix Park, where a trio of soldiers observed him peeping at a pair of temptresses. (Or he possibly exhibited himself, or might have masturbated in front of them; it’s never clear.) The second concerns his vague longing for his daughter, Isabel, who reminds Earwicker of his wife as a younger woman, and consequently recalls his own lost youth. Earwicker’s two sons—now rechristened Shem and Shaun—are in bitter opposition. Their sibling rivalry forms many of the book’s more tangled adventures. Additional characters include an elderly servant named Kate, twelve men who frequent Earwicker’s tavern, and four old men who appear in the capacity of judges. All of them adopt deeper roles as well.

And so, we get to the third iteration of this literary fractal. Here things get even more complicated. Characters pick up mythological associations, while identities destabilize and undergo displacement. Fortunately, Joyce provides us with a guide to this mythological face-dancing. Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker and Anna Livia Plurabelle appear in many places under many guises, but you can usually tell who’s who by the initials HCE or ALP.

In this third layer, HCE becomes something of a debased Zeus-like figure, a hero who sails in after the age of titans comes to a close. He then—

Hang on a moment! The titans?

Oh, yes—the fall of the titans. The book actually begins on this note, with the Fall of Finnegan. You know, the guy from that old Irish ballad, “Finnegan’s Wake?” But Finnegan is also Finn MacCool, the “titan” of ancient Ireland, and represents the old order of gods.

I warned you that this would get tricky! Before I go on, let’s take a detour and discuss the structure of Finnegans Wake.

Structure? Ha. Ha ha. You are very funny!

Believe it or not, there is a structure to the Wake. In a similar way that Joyce borrowed the framework of Ulysses from Homer, he structured Finnegans Wake around the theories of Giambattista Vico, author of The New Science (1725). Vico was an Italian philosopher who believed that history was an endless cycle proceeding in four main stages: the mythic-theological, the heroic-aristocratic, the human-democratic, and the chaotic ricorso. (Often paraphrased as the age of gods, the age of heroes, the age of man, and “the return.”)

Each age concludes with a Fall, which is heralded by the thunderous voice of God—represented by Joyce in the Wake as hundred-letter “thunderwords” such as the following:

The fall (bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntqnnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!) of a once wallstrait oldparr is retaled early in bed and later on life down through all christian minstrelsy.

Each Fall, of course, precipitates the next Rise, and therefore keeps the whole “velocopedal vicocyclometer” turning. (“Phall if you but will, rise you must” FW 4.15)

The text of Finnegans Wake is divided into four main parts, generally called “Books,” each representing a stage of Vico’s cycle. Each of these Books contains sub-cycles as well, as represented by “chapters,” sometimes called “episodes.” In Book I, two full cycles turn, so it contains 8 chapters. Book II and Book III each contain one full cycle, so they both have 4 chapters. Book IV contains one long chapter, a general “ricorso” sometimes called “Book IV, Chapter 0.”

In order to establish a sense of timelessness and to reflect this cyclical nature, the overall structure of the book is circular. Joyce felt that Finnegans Wake should been bound in a loop, so you could start reading anywhere, never really “finishing” the book, passing around and around again, absorbing more each time, a spiral winding its way into your mythic subconscious. (“Language is a virus,” whispers William S. Burroughs…) Indeed, the book begins in the middle of a broken sentence, its first half dangling at the end of the book, anxious for the cycle to begin again.

So the Fall of Finnegan represents the closing of a Viconian age? (Weren’t expecting me to pick that up so quick, you pretentious bastard?)

You’re getting pretty snarky for an imaginary projection, but yes. Joyce’s embodiment of the mythic cycle is Finnegan, the infamous hod-carrier from the song “Finnegan’s Wake.” (Note the apostrophe in the song is omitted in Joyce’s title. The most common error in writing about the book is misnaming it Finnegan’s Wake.) In the song, Tim Finnegan falls off a ladder and dies. During his wake, someone kindly spills whiskey on his lips and brings him back to life. (As Joyce knew, “whiskey” is the anglicized pronunciation of uisge beatha, Gaelic for “water of life.”) Needless to say, even the title of Finnegans Wake has multiple meanings, especially given the dreamlike nature of the book and the “fin: begin again” aspect of Viconian theory.

Though Tim Finnegan seems secure in his already legendary status, he has a deeper mythic resonance in the novel, and doubles for Fionn mac Cumhaill—usually anglicized as Finn MacCool—the giant from Irish legend. It’s the fall of Finnegan/Finn that opens the Wake and sets the stage for the coming of HCE, just as the titans had to be cast down so the gods of Olympus could muck about with dryads and golden showers, or Ragnarök’s Götterdämmerung threw the gods to the wolves to clear the table for heroes with spears and magic helmets.

That was a great episode of Bugs Bunny!

Yes it was! And Wagner is very much present in Finnegans Wake. Which brings us back to the mythic and historical aspects of our illustrious cast. In his mythic aspect HCE is Adam and Noah; he’s also the Flying Dutchman, Persse O’ Reilly, and Charles Stewart Parnell. He’s the Patriarch, representative of the Heroic age, who must one day step aside himself and allow his sons to take the stage. But HCE is compromised by guilt. His never-quite-defined actions in the park and his “insectuous longing” for Issy burden him with the stain of “original sin.” This anxiety sometimes manifests as stuttering; and as dark rumors about HCE spread throughout dear dreamy Dublin, he’ll eventually be sentenced to a similar “Phall” as Finnegan’s.

His wife, ALP, is all women—and all rivers. She is forgiveness and healing, Eve and Isis and Mary. It’s her role to begin as a fresh, tempting spring, to gather her powers as a river, and to finally wash the filth of men and their creations back to the womb of the great ocean—where she is taken to the heavens (via evaporation) to return again, the eternal feminine. In her younger emanation she is Isabel, her daughter, who fills the mythopoetic role of Iseult/Isolde, Tristan’s illicit love, and represents youth, beauty, and temptation. Issy is also the twin temptresses in the park, and occasionally breaks into the colors of the rainbow and the phases of the moon. In ALP’s older aspect she is Kate, the crone, “ygathering gnarlybird,” who picks up the pieces of man’s fall in preparation for the eternal renewal.

But it’s the brothers Shem and Shaun who get the most attention. These warring brothers are all warring brothers, and they pass through more mythological permutations than you can shake an ashplant walking stick at. They’re the Cain and Abel, the Moses und Aron of Finnegans Wake. Shem represents the artistic temperament, and at times, like the characters of Gabriel Conroy and Stephen Dedalus, he functions as an alter-ego for Joyce himself. (In one chapter, Joyce, as “Shem the Penman,” cheerfully subjects himself to self-parody.) Shem’s job is to uncover the Word and reveal the naked truth about humanity, but for this he is often vilified. Under other guises he is Mutt, Glugg, Nick, or Lucifer. His brother is “Shaun is the Postman.” His job is to deliver the Word; but by his very nature he changes it, corrupts it, censors it. Shaun is publisher, publicist, and politician. He is also warrior and despoiler. The Yang to his brother’s Yin, in other guises he is Jute, Yawn, Jaun, Chuff, and the Angel Michael. Alone they are incomplete—they must resolve themselves in the Father, in HCE.

And let’s not forget the twelve pub-crawling wake-goers, who occasionally represent society; and the four old men, annal-chroniclers and all-judges, call them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; and the three soldiers, who become the various forces of invasion….

Oh, heavens, let’s not forget! And the next iteration…?

At this point, my fractal metaphor must be abandoned, as the Wake becomes too diffused to be captured by another “iteration.” Suffice it to say that HCE, ALP, Shem, Shaun, Issy, and crew have many adventures as the night continues. There are dreams within dreams, letters within letters, and even a complete play—a drama which out-Gonzagos Hamlet, because in this play, the characters are played by actors, who themselves are portrayed by Shem and Shaun, who are manifestations of Jerry and Kevin, who are being dreamed by Mr. Porter, who is—ultimately!—being “dreamed” by James Joyce. Or, you know, Leopold Bloom.

I’m beginning to think I’m dreaming you.

It’s more the other way around, seeing as you’re merely a projection of my ideal reader, asking me—in a somewhat irreverent tone, I may add—leading questions about the Wake. In fact, I clearly brought you into existence way back in the fifth paragraph.

But your sarcasm is well-taken; it is confusing. In a very real sense, Finnegans Wake is being dreamed not only by its “characters”—whether Mr. Porter, HCE, Finn, ALP, Leopold Bloom, or that dying guy by the Liffey—but by its author, its readers, and all of humanity as well. In fact, this provocative notion has tempted some Joyceans to take things a step further, speculating that no dreamer exists at all. They claim that with no objective frames of reference, we can only assume the dream has a dreamer, and any notions of ascribing it to an author or character are illusions.

So, anything else you’d like to add before you banish me from existence?

Well, there’s one last thing I’d like to mention. Finnegans Wake is also about . . . Finnegans Wake. The text of Joyce’s final work is possessed by a charming awareness of itself and its attendant difficulties, an awareness that includes all of Joyce’s previous work. (Ulysses in particular has its nose tweaked on several occasions.) At the risk of sounding like the sort of fellow who wears aluminum foil on his head and passes out pamphlets at bus stations: Finnegans Wake seems uncannily alive, as if it’s aware of you reading it.

Of course, this is partly because the Wake is constantly chattering about itself, asking the reader sly questions and throwing up distractions and red herrings. But more importantly, the Wake feels alive because it seems to speak directly to you—a clever illusion, perhaps, but there it is. No reader must bring more to a text than a reader of the Wake, and in constructing meaning, you often find yourself mirrored in the shimmering language. (Hell, the damn thing even mentions me by name, and knows about my love for coffee and my desire to steal galley copies: “and ruching sleets off the coppeehouses.”)

It’s this playful self-awareness that attracts so many writers and critics to the Wake. Finnegans Wake is not just about itself; by extension, it encompasses all texts, as well as the acts of writing, printing, publishing, reading, glossing, annotating, and criticism. Countless scholars have used the Wake as a testing ground for theories about open texts, authorial intention, reader-response, the exhaustion of Modernism, the death of the author, and so on, ad nauseum. The Wake cheerfully accommodates them; then like a fickle lover, casually slips into the bed of the next rival. Finnegans Wake delights in interpretations, and no two readers read—or misread—it alike. Just take a stroll through all the books written about the Wake, and you’ll see all kinds of crazy stuff, from Qabbalistic treatises to one fellow who’s convinced the Wake is all about an obscure ritual from pagan Ireland! Perhaps it’s best to let the Wake speak for itself:

For that (the rapt one warns) is what papyr is meed of, made of, hides and hints and misses in prints. Till ye finally (though not yet endlike) meet with the acquaintance of Mister Typus, Mistress Tope and all the little typtopies. Filstup. So you need hardly spell me how every word will be bound over to carry three score and ten toptypsical readings throughout the book of Doublends Jined

—FW 20.10-16

OK, last question. Do normal people read the Wake? It seems…well, it seems like a cult. I’m getting definite cult vibes here. Very culty.

Look, you’re not wrong. Finnegans Wake is the most famous least-read book. To say it’s “more read about than actually read” is an understatement. I know hardcore Joyce fans that have read Ulysses multiple times but abandoned the Wake after ten pages. And who can blame them?

However, if you are reading this—you, sitting there at your computer or looking at your phone, you—if you made it this far into my explanation of Finnegans Wake; if you didn’t click away muttering “too long; didn’t read,” or bail at the first mention of “aposteriorious tongues”—if you made it all the way here, you gotta be curious, right? At the very least?

So let me be honest: Finnegans Wake is a cult novel. I don’t care what anyone else says: “Oh, anyone can read it!” That’s bullshit. This isn’t Ulysses. The Wake isn’t for everybody—and that’s completely okay! It has nothing to do with intelligence or literary prowess. It’s just not going to engage, amuse, please, or enthrall every reader.

But like all cults, once you’ve joined, it’s hard not to become evangelical. People who love Finnegans Wake really love Finnegans Wake! They rave about it, they’re inspired to make art about it, they even start Web sites attempting to lure new readers. As difficult as the book can be, the list of its enthusiastic supporters is a who’s-who of remarkable people. Samuel Beckett was an early supporter, as was Joseph Campbell, who wrote one of the first explications of the Wake. Anthony Burgess of A Clockwork Orange fame was obsessed by Finnegans Wake, as was Robert Anton Wilson, the science fiction writer who first exposed the Illuminati to global attention (all hail Eris!). Phillip K. Dick believed the Wake was a work of “cosmic consciousness.” (He also believed he was zapped by a pink space laser.) John Cage, Pierre Boulez, and Stephen Albert composed award-winning pieces of music inspired by the Wake. Murray Gell-Mann, the scientist who first theorized the existence of quarks, named his subatomic particle after a word plucked from the Wake. Which means that the entire material universe is literally founded on Finnegans Wake!

Anyway, if you’ve made it this far, thanks for sticking with me. So…

Wanna join a cult?

Advice for the First-Time Reader

There are several schools of thought on the best way to approach Finnegans Wake. Some believe you should arm yourself with a set of reference books and annotations, then set into the text like an archeologist on a dig. If this is your style, you should budget a few months at the very least, and engage with the book like you’re taking a self-guided class. Others think it’s best to read the Wake casually, passing over what seems like nonsense and savoring the passages you find striking. There are some readers who take years to read the Wake in piecemeal fashion, advancing the bookmark a few pages whenever the mood strikes them. Many readers believe the Wake is best read aloud, like poetry, taking delight as the puns roll trippingly off the tongue.

All of these are fine suggestions, each with pros and cons. My advice? You do you. Reading the Wake is an impressive achievement, and there’s no “right way” to approach it. After all, most people who start the Wake never finish it, and certainly no one claims to understand it completely. Take it at your own pace, and remember that most of all, Finnegans Wake is meant to be enjoyed.

Guidebooks

If you find yourself warming up to the Wake, you may wish to purchase a guidebook or two. There’s nearly a hundred published books about Finnegans Wake, and literally thousands of academic papers. While the Brazen Head’s “Finnegans Wake Criticism” pages attempt to bring order to this chaos, there’s three books I’d recommend to first-time readers. William York Tindall’s Reader’s Guide to Finnegans Wake offers a friendly walk-through of the text. He outlines the basic “plot” of each chapter, calling attention to the symbolic nature of the characters and how certain elements tend to recur. (Two solids alternatives to Tindall’s guide are John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake: A Plot Summary and Ed Epstein’s Guide Through Finnegans Wake.) To get a better understanding of the many references, allusions, and compound words, there’s Roland McHugh’s Annotations to Finnegans Wake. About the size of a phonebook, this volume arranges its annotations in a way that mirrors the pages of the Wake itself. While this creates a lot of white space, and doesn’t offer much help for digital readers, once you get used to the style it feels quite natural. My third recommendation is John Bishop’s Joyce’s Book of the Dark. Less of a guide than a celebration of the Wake, Bishop’s charming book is filled with insightful interpretations, typographical maps, linguistic flowcharts, and even anatomical diagrams.

Which Edition?

Unlike Ulysses, a reader of Finnegans Wake need not worry about multiple editions—all mainstream editions of Finnegans Wake are based on the 1939 Faber and Faber original. This is actually quite important, as literary convention has become accustomed to quoting the Wake by page and line numbers. For instance:

Three quarks for Muster Mark!

—FW 383.1

This quote may be found in the first line of page 383. In order to remain consistent, it’s critical that all versions have the same pagination. While there’s been various “corrected” editions throughout the years, all maintain the same 628 pages of text. This means readers are free to purchase which ever edition they find the most appealing. The three most common are detailed below.

Finnegans Wake

By James Joyce

Penguin Classics, 1999

The most popular version of Finnegans Wake in the United States.

Finnegans Wake

By James Joyce

Wordsworth Classics, 2012

This version has line numbers in the margins. May be a little distracting for some, but helps with quotations and annotations!

Finnegans Wake

By James Joyce

Alma Classics, 1999

Contains a nice introduction by Joyce scholar Sam Slote.

Brazen Head Resources

Finnegans Wake Criticism — A list of annotations, guides, and criticism published about Finnegans Wake.

Offsite Resources

Internet Archive: Full Text of Finnegans Wake

It ain’t pretty, but it’s all there!

Finnegans Wake (Annotated)

The entire text of Joyce’s novel online with clickable annotations.

Finnegans Wake Concordance

Promulgated by Eric Rosenbloom, this page holds a search engine that allows you to search the entire text of FW for words and strings. I tried “quail” and got “244.30 unlatched, the birds, tommelise too, quail silent. ii. Luathan?”

Finnegans Wake Wikipedia Page

Wikipedia’s Wake page is surprisingly detailed and informative.

James Joyce Digital Archive: Finnegans Wake

Edited by Danis Rose and John O’Hanlon, the JJDA “presents the complete compositional histories of Ulysses & Finnegans Wake in an interactive format for scholars, students and general readers.”

Waywords and Meansigns

An incredible project aiming to set all of Finnegans Wake to music!

Finnegans, Wake!

Peter Quadrino’s blog contains “interpretations, reflections, relevant links, and other information concerning James Joyce’s greatest but least-read masterpiece.” A treasure trove of insightful posts, essays, and book reviews!

Finnegans Web

Started in 2005, this Finnegans Wake wiki hasn’t been updated since July 2021, but its fascinating and useful resources are still available.

Wake In Progress

Stephen Crowe’s project to illustrate the Wake may have stalled in 2018, but the work accomplished is quite nice.

Finnegans Wake Society of New York

Founded in 1991 and known as the “Wake Watchers,” this society is devoted to the reading and explication of Finnegans Wake.

Joyce Works:

[Main Page | Dubliners | A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man | Ulysses | Finnegans Wake | Poetry | Exiles | Other Works]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 13 June 2024

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com