Joyce Music – Maxwell Davies: Missa super “L’homme armé”

- At June 11, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

[Missa super L’homme armé] is not so much a completion of a mass as a sacrifice of the mass itself, a splintering, a disintegration of the idea of the ritual—like the comedies I admire most, its underlying basis is tragic. Underneath the comedy there is a serious story of corruption.

—Peter Maxwell Davies, 1969

Missa super “L’homme armé”

(1968/71)

Music theatre for speaker, flute/piccolo, clarinet, percussion, harmonium, harpsichord/celesta/piano, violin and violoncello

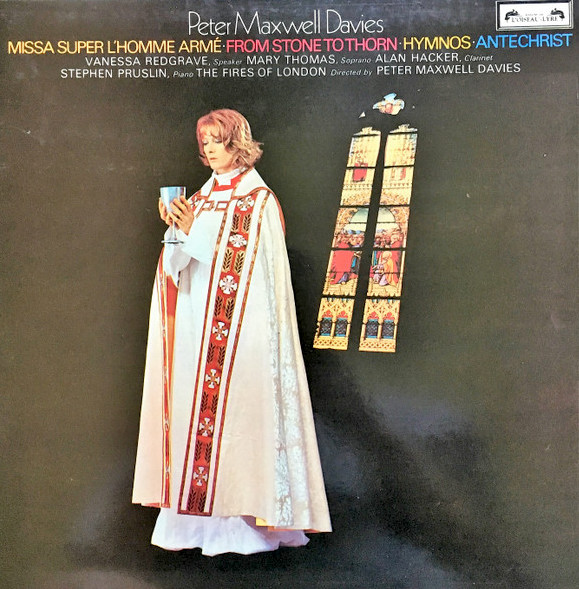

Scored for a Pierrot Lunaire-style ensemble with additional percussion, Missa super “L’homme armé” is a parody of a fifteenth-century mass based on a popular song, “L’homme armé,” or “The Armed Man.” Upon this cantus firmus, Maxwell Davies overlays passages from Luke 22, the Last Supper scene where Jesus informs his disciples of his imminent betrayal. Drawn from the Latin Vulgate, this text is read aloud by a speaker, usually a woman dressed like a priest or a monk; but if the speaker is male, the score instructs him to wear a nun’s habit. (On the original 1971 album cover, speaker Vanessa Redgrave is posed in full priestly regalia.)

Lasting around 18 minutes, Missa is vintage early Maxwell Davies—a cheerfully demented romp through a kaleidoscope of musical styles, overlayed with bizarrely unsettling vocals. Imagine a medieval version of Jethro Tull conducting mass at a carnival, with Punch and Judy as altar boys and the court jester offering a communion of kiss-my-arse. Every time the music settles into a harmonious turn it quickly disintegrates, atomizing into peeps and squeaks, imploding into furious scribblings, or scattered by a barrage of percussion. At times a pre-recorded church organ plays, the acetate deliberately scratched and distorted. As the needle begins skipping, the other instruments transform the repeating passage into a mocking cadenza. No instrument is safe from scorn or degradation—bells are gonged into silence, the harpsichord is trampled by cats, and wind instruments giggle, fart, and comically deflate like a phallus gone limp. The mass concludes with a surreal burlesque, a honkey-tonk piano careening out the vestibule while the speaker howls like a witch at sabbat: “Proditor! Proditor! Proditor!”—Traitor!

If this “Black Mass” evokes the “Circe” episode from Ulysses—complete with transvestite priest and unreliable narration—that’s no accident, as Missa was partly inspired by Joyce. Interestingly, however, Maxwell Davies cites the “Cyclops” episode and its belligerent Citizen as his primary influences:

“In the Joyce, a conversation in a tavern is interrupted by insertions which seize upon a small, passing idea in the main narrative, and amplify this, often out of all proportion, in a style which bears no relationship to the style of the germinal idea which sparked off the insertion. The insertion is often itself a parody—of a newspaper account of a fashionable wedding, or of the Anglican Creed, for instance.”

This “conversation in a tavern” may relate to the origins of the cantus firmus itself, as some scholars have speculated “L’homme armé” refers to Maison L’homme Armé, a popular tavern near Guillaume Du Fay, one of the first composers to incorporate the song into a mass. Du Fay was followed by many others, and “L’homme armé” persisted well into the Baroque period.

As Maxwell Davies describes, he “amplifies” his modern version of “L’homme armé” with a myriad of parodic insertions. While the original melody is occasionally sounded on handbells, the setting constantly twists itself into new musical forms—a lovely baroque trio nods to the popularity of the song into the seventeenth century, while a Victorian hymn parodies notions of morality and solemnity. The most famous of these “insertions” is a manic foxtrot. A common trope in Maxwell Davies’ early music, the sudden appearance of a foxtrot symbolizes the collapse of the sacred into the profane. It’s not difficult to hear the voice of Joyce’s Citizen in these eruptions, his ponderous declarations of national betrayal mocked by the very medium of expression. Indeed, if one scrapes away Luke’s gospel to expose the original lyrics of “L’homme armé,” a rather belligerent palimpsest is exposed, a European call to arms some musicologists believe was a warning against Turkish incursion:

The armed man should be feared.

Everywhere it has been proclaimed

That each man shall arm himself

With a coat of iron mail.

The armed man should be feared.

Words surely to please the Citizen!

Liner Notes (1971 L’Oiseau-Lyre LP)

By Sir Peter Maxwell Davies

Reprinted in: A Portrait

Decca, 2004

Missa super “L’homme armé” started as an exercise—a completion of incomplete sections of an anonymous fifteenth-century mass on the popular song L’homme armé, in fifteenth-century style. As I was working at this, other possibilities suggested themselves.

In form the work is similar to my Hymnos, for clarinet and piano—there are three sections, each divided into three subsections, corresponding to the three subsections of the original Agnus Dei of the mass. The eventual treatment stems from the chapter in the Ulysses of James Joyce corresponding to the Cyclops chapter in Homer. In the Joyce, a conversation in a tavern is interrupted by insertions which seize upon a small, passing idea in the main narrative, and amplify this, often out of all proportion, in a style which bears no relationship to the style of the germinal idea which sparked off the insertion. The insertion is often itself a parody—of a newspaper account of a fashionable wedding, or of the Anglican Creed, for instance.

In L’homme armé the first subsection presents the opening of the fifteenth-century Agnus Dei more or less straight, on the instruments, except that this is prefaced by a harmonisation of the tune L’homme armé in a popular song style, though not one of the fifteenth century. As the work progresses, however, the incomplete sections of the original Agnus Dei are filled out by music which transforms the basic material into ever more distantly related statements although the original, with an “in style” completion, may be present somewhere in the texture, perhaps distorted, setting up unorthodox relationships between foreground and background material.

Two of the “distortions” are pre-recorded on a 78 rpm disc on which an organ plays, first, a “faulty” fifteenth-century completion, in which a sticking needle is simulated in the recording, and later, a pseudo-Victorian hymn, with the speaker’s words “Ecce manus tradentis”. Fragments of texts from St Luke intersperse the purely instrumental music throughout. The work should perhaps be regarded as a progressive splintering of what is extant of the fifteenth-century original, with magnification and distortion of each splinter through many varied stylistic “mirrors”, finishing with a “dissolution” of it in the last automatic piano section.

Excerpt from Paul Griffith’s Peter Maxwell Davies

By Paul Griffiths

Peter Maxwell Davies

Robson Books, 1982

PARODY AND MUSIC THEATRE

The existence of the Pierrot Players, coupled with the completion of Taverner in 1968, released in Davies a torrent of creative energy to be poured into the composition of three important works of music theatre—Missa Super l’Homme Armé (1968, revised in 1971), Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969) and Vesalii Icones (also 1969)—along with other works for the new ensemble and a pair of orchestral scores, Worldes Blis (1966-9) and St. Thomas Wake (1969). But perhaps the most significant trigger in producing this outburst was another work dating from the Taverner years though not performed until 1968, Revelation and Fall for soprano and sixteen players (1966). Here, in setting a prose poem by Trakl, Davies faced the need to re-experience the savagery, the dislocation and the sense of catastrophe that inform so much of the art of the few years before the First World War, and, as it now seems inevitably, it was to Schoenberg, especially to Pierrot Lunaire, that he turned for the means to cope.

By contrast with the largely syllabic, declamatory style of vocal writing in Taverner, the singer’s part in Revelation and Fall is an extraordinary virtuoso assault, requiring a range of almost three octaves, several different kinds of delivery, and the ability to negotiate complex rhythms and rapid, jagged melismas. The aim is to articulate the shriek of desperation in the Trakl text, yet at the same time the music does everything in its power to stave off the point at which that shriek becomes inevitable. If it had not done so, then the whole thing might have collapsed into incoherence and banality, against which Davies, like Schoenberg in Pierrot Lunaire, fights with the weapons of compositional artifice. To quote his own remarks from the score, the work ‘represents a marked extension, in comparison with my earlier works in the use of late medieval/ renaissance composition techniques … in the complexity of rhythmic relationships between simultaneous “voices”, in the use of cantus firmus with long melismas branching out, and in the use of mensural canon’. Not only that, but it is also securely structured as a piece of thoroughly developing chamber music, being in this respect even more traditional than such a work as the String Quartet. After the introductory sequence, which ends with a little ‘chorale-canon’, there is a long purely instrumental allegro in which Davies applies his technique of progressive thematic distortion. Moreover, the distinct segments of the work are carefully bound together by thematic links involving plainsong ideas, and there is even a wholesale recapitulation, albeit with the original vocal line reassigned to wind soloists (bars 265-303, cf. bars 137-74). The strenuous seriousness of the music, which is ironically twisted but by no means undermined when the band slips towards dance music at the voice’s invocation ‘O bitterer Tod’, creates a context in which the soprano’s most extreme outburst, screamed into a loudhailer, can come as a real shock though it is also a real necessity, all other avenues of expression having been explored.

Indeed, the terror of Revelation and Fall is sufficiently well established musically to justify the quasi-theatrical presentation Davies has preferred, with the soprano appearing in blood-red nun’s habit to act the part of Trakl’s ‘Sister’. However, it was only in the works of 1968-9 that he was to take full advantage of the concert hall as theatre. In Missa Super l’Homme Armé the vocal soloist, singer or actor, is again a religious, though vested in robes belonging to the opposite sex as an outward mark of the whole work’s Antechrist-like inversion of meaning. However, it should be noted that the work was in its first version not a dramatic piece, the words being delivered by a boy’s voice on tape, and in that version it was more nearly an extrovert cousin to Ecce Manus Tradentis, whose text in both versions it largely shares. What is new in Missa Super l’Homme Armé is, therefore, not the subject matter, which is again spiritual betrayal, but the range and vividness of the musical imagery that Antechrist had made possible.

Working, as it were, inside the Agnus Dei from an anonymous unfinished L’Homme Armé mass, Davies uses all the parody techniques of Antechrist and more to distort the original into unexpected directions. There are the same parody gestures—the inappropriate and exaggerated expressive effects, the unbalanced textures and the extreme registers—joined by parody imitations, when the material is bent into the mould of a baroque trio sonata, or a sentimental Victorian hymn, or a foxtrot, and the appearance of these musical mockeries, which unlike the dances of Taverner or Shakespeare Music are viciously loaded and quite out of place, is profoundly disturbing. It is, of course, equally disturbing to conventional religious feeling that a parody hymn, already placed under suspicion in being allotted to the harmonium, should be associated with Judas’s betrayal, and that Christ’s curse on the traitor should be exclaimed by a transvestite nun who should ‘at the end of the piece foxtrot out, perhaps pulling off his wimple’. Yet by no means is Missa Super l’Homme Armé a cheap exercise in blasphemy. The questions it raises are those of discerning and communicating religious truth, and in particular of distinguishing what is true from its precise opposite: questions which had been raised but not resolved in Taverner and other works, and which were to be examined again still more searchingly in Vesalii Icones. At the same time, the ninefold structure of Missa Super l’Homme Armé, a feature also of the virtuoso clarinet piece, Hymnos (1967), and the sextet, Stedman Caters (1968), suggests that the source of difficulty may still be the Trinity-Incarnation paradox of Taverner and Antechrist.

Excerpt from an Interview with Peter Maxwell Davies

Paul Griffiths Interviews Maxwell Davies in London, 21 May 1980

Peter Maxwell Davies

Robson Books, 1982

‘Eight Songs’ was unusual among your theatre pieces in that you used a text by someone else.

Yes, that was Randolph Stow. I met him first in New York and then in Australia, and we had the idea of collaborating on something—poems set to music as a concert piece, or whatever. He came up with this idea of doing something on George III, and at first it wasn’t going to be a music-theatre piece, but then I had this extraordinary idea of putting the players in cages and making the king interact with them. That was when the poems were already under way and I’d got the first two. The other odd thing about Eight Songs was the idea of taking lots of different materials and putting them together. I’ve never gone in for a very simple montage of unrelated objects which, for instance, Berio has done. To me it’s always been much more appealing to take something where you can actually sense the distortion process happening.

As in “Missa Super L’Homme Armé”?

Yes. There again the material presented itself to my mind without my being in control of it. I was doodling, if you like, and the material I was working with, the original anonymous L’Homme Armé mass, was making me laugh by distorting itself into all sorts of funny musical images, and I wrote them down. It just seemed to be a very natural product of something that was in my mind anyway—an extension, I suppose, of the grotesqueries in Revelation and Fall. And there are also parallels in visual art: not only the gargoyles and so on in medieval art but also things like Ensor and Grosz and Bacon. It seemed to be part of the atmosphere of the time.

Does it worry you that people don’t know how to react to works like ‘Eight Songs and ‘L’Homme Armé’, where something that starts out being serious suddenly turns, say, into a foxtrot?

I think this is something that people rather enjoy coming to terms with and thinking about. I don’t think they object to that—all right, in the first instance they did object and found it all very disturbing.

But surely those works are still intensely disturbing, because if a work is, in effect, mocking parts of itself, then one has nothing that one can with certainty take seriously.

Yes, exactly, and that’s the intention. When I say these pieces aren’t disturbing any more, I just mean they don’t any longer create the kind of silly superficial disturbance which gets in the way of actually understanding a piece. On a deep level I think the music still is disturbing, and I hope it will go on being so.

I remember at that stage having an obsession with masks: the jester’s mask, for instance, in Taverner, where it’s quite an important thing, particularly when it’s removed. What’s the mask? Is the thing underneath still a mask? Then there’s Blind Man’s Buff, which is one of the tightest expressions of this whole preoccupation with what is real and what is not real, what is meant and what is parody, and exactly what is parody.

I think of a parallel with Liszt’s ‘Faust Symphony’, where the ‘Mephisto’ movement parodies, almost in your own vicious terms, what has gone before. But then he redeems the whole thing with this great closing chorus. There’s never any redemption in your music: one’s left really not knowing what to take seriously.

Absolutely! No comment.

Excerpt from the Essay: “Davies, Berio, and Ulysses”

By Murat Eyuboglu

Bronze by Gold: Joyce and Music

Garland Publishing, 1999

The two pieces I would now like to discuss in greater detail are in different manners both richly informed by their composers’ reading of Joyce. In his introduction to the score of Missa Super L’Homme Armé Peter Maxwell Davies articulates the Joycean connection when he writes that “the eventual treatment [of the work] stems from the chapter in the Ulysses of Joyce corresponding to the Cyclops chapter in Homer.” In order to investigate the nature and significance of the Joycean parallel, however, we need to start by tracing the many different layers of the work’s conception and the parodized historical references operating therein.

At every level of its compositional process Maxwell Davies’s Missa Super L’Homme Armé engages a historical antecedent, and thus creates a hall-of-mirrors effect in which techniques, styles, and genres of the past parade before our ears. The work that most fully underlies the conception of the Missa is Arnold Schoenberg’s theatrical Pierrot Lunaire from 1912. The instrumental ensemble for which Davies’s Missa is written, called the Pierrot Players, was not only named after Schoenberg’s work, but it reproduced the instrumental combination of its model, with the addition of a percussionist. Maxwell Davies and his friends Harrison Birtwistle, Alan Hacker, and Stephen Pruslin were interested in both the ensemble combination and in the theatrical aspects of Pierrot Lunaire: staging of Schoenberg’s work, in other words, was among the foremost objectives of the Pierrot Players. Schoenberg’s employment of Sprechgesang (speech-song) to evoke, in Pierre Boulez’s words, a cabaret noir that flirts with bad taste, its ensemble that integrates rather than features the piano in a configuration of timbres that vary throughout the piece, and its use of learned baroque or Renaissance styles to parodic ends, are influences that permeate Davies’s Missa.

On a historically remote, yet programmatically available level, the Missa parodies the Parody Mass. The Parody Mass, a genre that flourished in the sixteenth century and was baptized Missa Parodia by Jakob Paix in 1587, entails the compositional practice of borrowing the entire polyphonic texture of a secular song of motet and subjecting it to various transformations in the form of a mass. The word “parody” in Parody Mass does not imply an ironic inversion or satire, but rather testifies to the free circulation of musical material, unencumbered by notions of originality and ownership. Davies’s Missa, on the other hand, ironizes the notion of completion, which is essential to the sixteenth-century genre, when the narrator of the piece madly foxtrots off the stage to the accompaniment of an out-of-tune honky-tonk piano, which itself gets cut off in midstream.

Although no staging is required for the Missa, its speaker, who recites an abbreviated and reordered version of the Last Supper from Luke 22, appears in costume. In his stage directions Davies writes that “the speaker should be dressed as a nun if taken by a man, or as a monk if by a woman.” While the biblical themes of betrayal and communion are being spelled out by the speaker, the instrumental sections present a plethora of readily recognizable musical styles: the work opens with a statement of a section from an anonymous fifteenth-century mass based on the popular tune L’homme armé. The theme of the borrowed mass is later cast in the foxtrot style, tremendously popular in the 1920s and 1930s. A section in the style of a hymn is accompanied by the speaker’s words: “And he [Judas] promised, and sought opportunity to betray him unto them in the absence of the multitude.” The section that follows in baroque style bears the score indication: “like a bad gamba; sharp on higher notes, scratchy and swoopy.” Later, the foxtrot idea is once again taken up and this time cast in Tempo di quickstep. It is in this parodic revisiting of at times unrelated styles, against a narration ending with hysterically reiterated charges of betrayal—“but behold, the hand of him that betrayeth me is with me on the table”—that Davies establishes the parallel with “Cyclops.” He continues his introduction as follows:

The eventual treatment stems from the chapter in the Ulysses of Joyce corresponding to the Cyclops chapter in Homer. In the Joyce, a conversation in a tavern is interrupted by insertions which seize upon a small, passing idea in the main narrative, and amplify this, often out of all proportion, in a style which bears no relationship to the style of the germinal idea which sparked off the insertion.

“Cyclops” captures the distracted and haphazard nature of a “confab” at Barney Kieran’s bar where a fanatic Irish nationalist, the “Citizen,” fulminates with increasing vociferousness against Bloom on account of the protagonist’s perceived Jewishness. A unique feature of the chapter is the asides that Joyce inserts into the narrative. At times directly, at others remotely triggered by themes from the main narrative, these asides reproduce nineteenth-century styles of writing such as medical, legalese, journalistic, epic-revivalist, religious, and political prose. We could call these asides examples of pastiche had Joyce simply reproduced their style, emphasizing primarily the similarity between the original style and his simulation of it. Most of the asides, however, are ironized through parody and thus expose a difference from, rather than a similarity to, the original. Although there is a definite centrifugal tendency in Joyce’s writing, an illusion of uncontrolled proliferation (an effect replicated, as we shall see, in Berio’s Sinfonia), the thematic patterns of the asides in “Cyclops” are fairly perceptible: an account of the first-person narrator’s activities as a “Collector of bad and doubtful debts” (U, 12.24-25) is followed by a pastiche of legalese language; a conversation about a hanged man’s erection is followed by a parody of a medical journal style where the phenomenon of postmortem erection is given “scientific” explanation (U, 12.468-78). Most of the Irish revivalist asides parody a nationalism that cherishes the glamorous past of a serene homeland. The grotesque figure of the Citizen, parodying Homer’s brutish Cyclops, is (in)directly teased through these asides. In addition to the historical sense conveyed through the asides, as Dominic Manganiello’s Joyce’s Politics demonstrates, an intricate historical background dealing with the debates among Arthur Griffith, Francis Skeffington, and others, concerning Home Rule, Sinn Féin, and nationhood in general, can be traced within the chapter.

How deeply and at what levels does “Cyclops” inform Davies’s Missa? Davies cites only the centrifugal and refractory narrative structure of the chapter, without, however, engaging in the centripetal and historical thematicization of its model. While Davies’s parodic evocation of Renaissance, baroque, and foxtrot styles simulates a certain sense of history, this evocation stops short of establishing a historically specific referentiality. If it is unfair to expect of a musical work to reproduce the intricacies of Joycean prose, we may then ask, at What other levels does Davies’s work enter into a dialogue with Ulysses?

A reading of the “Circe” chapter, although not mentioned by Davies, reveals significant correspondences between Ulysses and the Missa. Although Stephen’s chanting of “the introit for paschal time” (U, 15.74) at the beginning of “Circe” sets the tone for the mass, it is actually the Black Mass presided over by the cross-dressed Father Malachi O’Flynn toward the end of the chapter that seems to have served as the model for Davies’s Missa:

([…] Father Malachi O’Flynn in a lace petticoat and reversed chasuble, his two left feet back to the front, celebrates camp mass. The Reverend Mr Hugh C Haines Love M. A. in a plain cassock and mortarboard, his head and collar back to the front, holds over the celebrant’s head an open umbrella.)

FATHER MALACHI O’FLYNN

Introibo ad altar diaboli.

THE REVEREND MR HAINES LOVE

To the devil which hath made glad my young days.

FATHER MALACHI O’FLYNN

(takes from the chalice and elevates a blooddripping host) Corpus meum.

THE REVEREND MR HAINES LOVE

(raises high behind the celebrant’s petticoat, revealing his grey bare hairy buttocks between which a carrot is stuck) My body.

THE VOICE OF ALL THE DAMNED

Htengier Tnetopinmo Dog Drol eht rof, Aiulella!

(From on high the voice of Adonai calls.)

ADONAI

Dooooooooooog!

THE VOICE OF ALL THE BLESSED

Alleluia, for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth!

(From on high the voice of Adonai calls.)

ADONAI

Goooooooooood!

(U, 15.4693-716)

This passage, echoing Buck Mulligan’s mock-mass at the opening of Ulysses, presents the church and cheater in satirical contiguity. Cheryl Herr, in her Joyce’s Anatomy of Culture, richly documents the traditions of parodic sermonizing and transvestism in the music halls of Ireland (136-88, 222-55). In fact, it is the theatricality and the popular cultural aspects shared by the music hall and the church that lead Joyce and Davies to create images where stage acts and religious ceremonies appear in conflation. A communion service led by a cross-dressed priest appears in both “Circe” and the Missa. Another intriguing correspondence is the use of the gramophone that in “Circe” blares “The Holy City” of Stephen Adams. Although the music of “The Holy City” does not appear in Davies’s work, the distortion effect—“Whorusalaminyourhighhohhhh….”—that occurs in “Circe” when “the disc rasps gratingly against the needle” (U, 15.2211-12), causing the three whores to cover their ears, is replicated in the Missa. These further correspondences with “Circe” explain to a limited extent the origin of the theatrical elements in the Missa. The intricate context that Ulysses provides for the themes of transvestism, the mass, and the music hall, however, are absent in the Missa. Once again, the theatricality of the Missa is void of the historical context of its model in Ulysses.

Recordings

|

|

Maxwell Davies: Missa Super l’Homme Armé (1971)

Conductor: Peter Maxwell Davies

Musicians: Fires of London

Speaker: Vanessa Redgrave

LP: Missa Super l’Homme Armé, From Stone to Thorn, Hymnos, Antechrist. L’Oiseau-Lyre DSLO 2 (1971)

CD: A Portrait. Decca 475 6166 (2004)

Purchase: LP [eBay], CD [Amazon | Presto Music]

Missa super “L’homme armé” was originally released on LP in 1971 by Decca/L’Oiseau-Lyre and had several reissues throughout the 1970s. In 2004 Decca finally released Missa on CD, part of a two-disc compilation of Maxwell Davies’ early works called A Portrait. While Amazon usually has used copies available, Presto Music uses a print-on-demand model that’s much cheaper. This 1971 recording remains the only version of Missa commercially available. It features the always-game Vanessa Redgrave as the transvestite “priest.” As a side note, that same year Redgrave portrayed the beyond-controversial Sister Jeanne des Anges in Ken Russell’s film The Devils, which featured a soundtrack by, naturally, Peter Maxwell Davies.

Streaming

The following recordings are available online.

Maxwell Davies: Missa super “L’homme armé” [Soundcloud]

Psappha Ensemble, 2004

The amazing Psappha Ensemble has been closely associated with Sir Peter Maxwell Davies since its conception. This version of Missa was conducted by Nicholas Kok, with Fiona Shaw as the speaker. It was recorded live at the Royal Albert Hall on 8th September 2004. Shaw sounds considerably more deranged than Vanessa Redgrave, and her concluding “Proditor!” is a baleful shriek of pure spite. As usual, the Psappha Ensemble plays magnificently, leaning enthusiastically into the musical anachronisms.

Online Video

The following live performances are available on YouTube.

Missa super “L’homme armé” [Excerpt]

An excerpt of a live performance recorded 7 October 2014 at the Musica Francesci Filidéi Palais universitaire in Strasbourg. I actually have no idea what the hell this is; whether it’s some bizarre adaptation of Maxwell Davies’ piece, some new prologue to the Missa, or something simply sharing the same name. But it’s…worth watching. Sort of Spike Jones-meets-Kraftwerk?

Additional Information

Missa Score

Boosey & Hawkes published the score of Missa super “L’homme armé” in 1980.

Wikipedia: L’homme armé

You can listen to the original song on Wikipedia.

Guillaume Du Fay’s L’Homme armé

Micheline Walker has an informative post about the source material for Maxwell Davies’ Missa.

Pre-Existent Music in the Works of Peter Maxwell Davies

Cheryl Tongier’s 1983 dissertation features several pages devoted to Missa super “L’homme armé.”

Paywall:

Resurrecting the Antichrist: Maxwell Davies and Parody—Dialectics or Deconstruction?

Tempo New Series, No. 191 (Dec., 1994), pp. 14-17+19-20. Although Steve Sweeney-Turner primarily discusses Maxwell Davies’ Vesalii Icones, Missa super “L’homme armé” is mentioned. [JSTOR]

Sources and Notes

When writing about Missa super L’homme armé, several valid choices of capitalization present themselves. Even Peter Maxwell Davies couldn’t settle on which version to use! I have adopted the predominately lower-case title printed on my compact disc. However, when quoting from other sources such as interviews and essays, I have retained the capitalization scheme of the original source.

I am indebted to Murat Eyuboglu for calling my attention to the relationships between Maxwell Davies’ Missa and Joyce’s “Circe” episode. After reading his compelling essay, “Davies, Berio, and Ulysses” I found it impossible not to think of Missa as a reflection of “Circe” along with “Cyclops.” My review reflects this connection, as does the banner image that heads the page. Also, the English translation of the French lyrics to “L’homme armé” was borrowed from Wikipedia, where it remains unfortunately uncredited.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 19 June 2024

Return to: Sir Peter Maxwell Davies Page

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com