Joyce Music – Lerdahl: Wake

- At October 30, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I don’t think in terms of the public… Music is for the musicians. If the public wants to come along and study it, fine. I don’t go and try to tell a scientist his business because I don’t know anything about it. Music is just the same way. Music is not entertainment.

—Bethany Beardslee, 1961

Wake

(1968)

For soprano, harp, string trio, and percussion. Text arranged from Finnegans Wake

Composed in 1968 when Lerdahl was composer-in-residence at Vermont’s Marlboro Music Festival, Wake is a 16-minute tour de force for soprano. It was written for Bethany Beardslee, the American singer whose uncompromising approach to the avant-garde was forged working with figures such as Pierre Boulez, Milton Babbitt, and Peter Maxwell Davies. Both Lerdahl and Beardslee shared an admiration for Arnold Schönberg, whose seminal work Pierrot Lunaire exerts a distinctive influence over Wake, from its restless atonality to its exceptional demands on the singer. Wake also shares a certain thematic kinship with Pierrot Lunaire as well. Drawn from the “washerwomen” sequence in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Lerdahl’s lyrics hold a surreal mirror to “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” the fourth of Albert Giraud’s Pierrot Lunaire poems set by Schönberg:

A pallid laundry maid,

Washes faded laundry,

Her bare silver arms

Thread downward to the river.

From the trees a gentle breeze plays

Softly through the reeds.

A pallid laundry maid

Washes faded laundry.

The heavenly and sweet laundress

Tying up her skirt,

By the branches softly caressed,

Hangs her linen of moonlight,

A pallid laundry maid.

*English translation by Brian Cohen

Wake is loosely divided into three thematic sections, called “cycles” by Lerdahl. The first introduces Joyce’s washerwomen, a pair of Dublin crones eager to “tell us all about” Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker and his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle, Joyce’s feminine incarnation of the River Liffey, and by extension all rivers. The second part offers a preamble for the tale of young ALP, suggesting that sadness and grief are just around the corner. However, before the juicy gossip can be heard, the washerwomen are silenced by the approach of nightfall. They are slowly transformed into tree and stone, merging with the landscape “beside the rivering waters.” The sequence is one of the most famous in Finnegans Wake, published separately from Work In Progress in 1928 as Anna Livia Plurabelle. Joyce even made a recording of himself reading from the episode. Two decades after Lerdahl’s Wake, Joyce’s “washerwomen” sequence would inspire another American composer, and Stephen Albert would win the Pulitzer Prize for his Symphony RiverRun.

Scored for a string trio, harp, and percussion, Fred Lerdahl’s Wake is dynamic and unpredictable. Like its literary namesake, no two samples taken at random are quite alike, yet remain characteristically “Wakean,” expressing a distinctive semantic/musical universe. While the orchestration is certainly impressive, it’s the vocals that truly astonish, and it’s difficult to imagine anyone quite matching Beardslee’s stunning performance. (Perhaps Cathy Berberian; or today, Barbara Hannigan?) In any event, there’s only one recording of Wake available, so it seems disingenuous to discuss the piece without referencing its miraculous star.

Wake opens with the fractured line, “But toms will till. Will toms till but. Till but toms will.” Beardslee delivers this in a wavering, sing-song voice, accompanied by sporadic drums—clearly the toms in question, which echo the “fall” of HCE (and thereby all mankind), and continue to sound throughout the entirety of the piece.

The first cycle opens with a plea: “Tell me all…” Beardslee effortlessly incorporates Joyce’s mercurial text into her fractured aria, some lyrics sent soaring into the stratosphere and others spat in staccato bursts. Words and lines are often repeated neurotically, stuttering thoughts demanding expulsion. This erratic delivery creates a sense of “worrying away” at the text, as if the lyrics are being gnawed from a protean churn of language. Beardslee demonstrates a full grasp of Joyce’s complex wordplay, pronouncing “doomsdag” like a German day of the week and touching Joyce’s “river puns” with the perfect amount of ambiguity. (A close listen of Wake demands reading along with the text, otherwise the brain transforms the lyrics into a mere collage of meaningless phonemes.) The orchestra becomes increasingly agitated as the cycle progresses, percussion fumbling its way through a turbulence of strings and sharply-plucked harp. The cycle concludes with “her bulls were ruhring, surfed with spree,” each repetition growing more shrill and demanding, the final “spree” threatening to shatter glassware.

A brief transition—or as Lerdahl would later refer to it, an “episode”—follows: “Do tell us about” syllabically machine-gunned in coloratura soprano. It’s here one detects another of Lerdahl’s musical influences, the Hungarian composer György Ligeti, and the vocals anticipate the sputtering aria delivered by Gepopo, the Chief of Secret Police in Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre.

The second cycle begins with surprising tranquility, a hushed expectation of the story to come. “She was just a young thin pale soft shy slim slip of a thing” is suitably tender, a wandering harp sounding over crying violins. The strings grow even more dramatic, with shades of Shostakovich coloring the “deep dark, stagnant pools.” The music again rises to a kind of crescendo, less frantic than the first cycle, but establishing a pattern nonetheless, a “millwheeling vicociclometer” in musical miniature.

The final transition urges the storyteller to continue, exciting percussion underscoring “calamity electrifies man.” A quiet figure repeated in the strings announces the coming dusk: “Tys Elvenland!” As the third cycle begins, the washerwomen abandon their tale and begin transforming, the fragmenting orchestra echoing their metamorphosis into mineral and wood. Tremulous violin and sparse, celestial harp establish an atmosphere of subdued mystery. This otherworldliness is reflected in the vocals, a restless, atonal aria recalling the probing anxieties of Schönberg’s Erwartung or Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. There’s one final surge of panic—“Night now! … Night night!”—but weariness and resignation follow, the conversation now a self-told tale of “stem and stone.” The instruments fade with the singer. The subsequent silence feels like part of the score itself; a Cagean element as essential as the blank space ending Book I of Joyce’s inscrutable novel.

Interview with Fred Lerdahl

In December 2022, Allen Ruch of the Modern Word talked to Fred Lerdahl about Wake.

Allen B. Ruch: Hello, and thank you for agreeing to talk about Wake! I know the piece is over fifty years old. What are your feelings now when you hear it? Does it hold any special place for you?

Fred Lerdahl: It’s hard to believe that Wake is over 50 years old. I remain proud of it. It was my breakthrough piece—the first piece that received significant success and that anticipated features of my mature compositional style.

ABR: The text of Wake is derived from the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” episode of Finnegans Wake. What was your first exposure to James Joyce?

Fred Lerdahl: While in college, I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Dubliners. In my early 20s, I immersed myself in Ulysses. Joyce’s experimental impulse, beautiful language, and deep humanity attracted me. It was natural to move on to Finnegans Wake, but I found the language difficult and the characters too abstract; much as I admired portions of the novel, I never got all the way through it.

ABR: What in particular attracted you to the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” episode?

FL: The language and imagery of the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” episode is particularly poetic.

ABR: Finnegans Wake has a long tradition of being influential among the musical avant-garde. John Cage, Pierre Boulez, Luciano Berio, and György Ligeti have all cited the Wake as inspirational to some degree or another, and have responded to the Wake with music. Do you see your own composition as part of this avant-garde “conversation,” or did you approach Finnegans Wake from a different direction?

FL: Wake is modernist but not avant-garde. I responded to Finnegans Wake’s language and cyclic form.

ABR: In your liner notes, you’ve indicated that you “cut up” and rearranged Joyce’s text to “reflect the themes of the book as a whole.” First of all, “cut up” is a somewhat loaded term—should we simply take this literally, or was there any Burroughsian or aleatoric approach involved in the composition?

FL: Perhaps “cut up” was the wrong expression. There is nothing of Burroughs or aleatoricism in my music.

ABR: Can you explain your process; how you approached this formidable task?

FL: The cyclic view of history, and even of individual life, attracted me not only in a general way but also in its potential for musical form. Much of my later music incorporates spirals, arches, and cycles. Wake was my first attempt in this direction. I selected and arranged excerpts from Joyce’s text to build a cyclic form, always keeping in mind the music that I was imagining.

ABR: Luciano Berio had Cathy Berberian as an interpreter, and wrote many of his vocal pieces with her voice deliberately in mind—including most of his Joyce-inspired works. How much of Wake’s text, or your setting/arrangement of the text, was a response to Bethany Beardslee’s unique voice? And, like Berberian with Berio, was Beardslee also a creative/collaborative partner in the writing?

FL: Bethany Beardslee and I were fellows at the Marlboro Music Festival in the summer of 1967. She encouraged me to write a piece for her. I knew her voice well and wrote Wake with it in mind. I brought the completed piece to Marlboro in summer 1968 and coached her extensively, playing passages on the piano as she learned the difficult pitches and rhythms. She premiered Wake with Marlboro players later that summer; I conducted.

The situation was different for Berio and Berberian. She played an active creative role in the conception and realization of his vocal writing.

Bethany Beardslee 1964 (Photo: Abisag Tüllmann)

ABR: Beardslee’s reading of the text highlights her astonishing range and versatility; but it also reveals an informed sensitivity to Joyce’s multilingual puns. Was Beardslee herself familiar with Finnegans Wake? If not, what was her reaction to Joyce’s “nat-language?”

FL: Bethany was intuitive, not intellectual, and, I believe, never read Finnegans Wake. But she responded to Joyce’s language.

ABR: The “Anna Livia Plurabelle” passage has been set to music many times, beginning in 1935 with Hazel Feldman. In her notes, she indicates her setting was inspired by the 1929 recording of Joyce reading from Anna Livia Plurabelle. Were you familiar with this recording when you were writing Wake? And if so, how did it impact your writing, if at all?

FL: I didn’t hear Joyce’s recording until years later. Probably this was for the better; if I had known it, I would have felt constricted. In truth, Wake isn’t very faithful to the tone of Finnegans Wake. It rests on its own merits, not because it enhances its literary source.

ABR: In the liner notes to the 2013 Bridge release of Wake, you wrote, “Composing it was exhausting, and after it was finished I went through a long crisis in search of a coherent musical language.” What in particular did you find exhausting? And how exactly did Wake precipitate a musical crisis?

FL: Wake was written in a free atonal way—that is, without an explicit harmonic syntax or compositional method. I had rejected serialism, which was dominant in the day, and lacked an alternative to fall back on. I composed by ear, so to speak. All composers do this to some extent, but, depending on temperament, most also rely on this or that method to guide their intuitions. Otherwise one is overwhelmed by a million possibilities at every turn. Because of the lack of syntax, much of my early music, including Wake, relied heavily on text setting; the words helped shape the music. I found the absence of compositional method exhausting and, after completing the piece, determined to forge my own musical syntax based on principles of music cognition. (My recent book Composition and Cognition: Reflections on Contemporary Music and the Musical Mind discusses the crisis I went through and how I resolved it.)

ABR: Aside from James Joyce, you’ve set poems by Ezra Pound, Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, and a few others. You’ve also cited Samuel Beckett and T.S. Eliot as inspirations on Aftermath. Given some of these names, is it fair to say you have an attraction to literary modernism? And, do you ever return to a writer for inspiration?

FL: As a young man, I immersed myself in Yeats, Pound, Eliot, Joyce, and Beckett. I continue to love that literature. I do not return to a particular writer for inspiration, but the study of prosody is indeed an ongoing source of inspiration.

ABR: Thank you, and I look forward to hearing your next piece!

Liner Notes (Acoustic Research LP 1970)

By Donald Sur

Milton Babbitt: Philomel; Fred Lerdahl: Wake

Acoustic Research, 1970

Fred Lerdahl was born in Madison, Wisconsin in 1943 and began composing at age 15. He received a Bachelor of Music at Lawrence University (Appleton, Wisconsin) and a Master of Fine Arts at Princeton University. He received a Koussevitsky Composition Prize at Tanglewood in 1966 and has served as composer-in-residence at the Marlboro Music Festival. He was also a Fulbright scholar in Germany in 1968 and is presently teaching at the University of California, Berkeley.

Wake was composed in 1967-1968 and received its premiere on August 14, 1968 at the Marlboro Music Festival with Bethany Beardslee as soprano soloist and the composer conducting. The text, taken from Book I, Chapter 8 of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, was arranged by the composer in an attempt to reflect the structure and major themes of the book. Listeners who know Joyce’s recorded reading from this chapter will recall the unusual poetic intensity of the passage and be grateful for the excerption. The piece is divided into three “cycles” with introduction, transitions, and coda. Washerwomen are gossiping at the ford: Cycle I is concerned with gossip of Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker; Cycle II with Anna Livia Plurabelle, his wife; Cycle III with the gradual dissolution of the scene into night. Repeated passages contribute an interesting dimension in the unfolding of the piece suggesting also the theme of recurrence which is a major concern of the book. A generous use of percussion evokes suggestions of the “Fall” in its multifarious manifestations in the books, Humpty Dumpty’s fall from the wall (Humpty being a manifestation of the hero of the book), etc. The piece is scored for soprano, harp, string trio and percussion.

Liner Notes (CRI CD 1990)

By Fred Lerdahl

Lerdahl: Waltzes, Eros, Fantasy Etudes, Wake

CRI, 1990

During the summer of 1967 and 1968, while still a graduate student, I had the good fortune to be a composer-in-residence at the Marlboro Music Festival. Bethany Beardslee, the already legendary diva of contemporary music, also spent those summers there. I wrote Wake for her. Accompanying the soprano here are violin, viola, cello, harp, and percussion (three players). Beardslee premiered the work under my direction at Marlboro in 1968. This recording, originally released on the AR-DGG series, dates from 1971.

Wake is the best fruit of my first period, which might be described as “post-Schoenbergian atonal/romantic.” (I have never been a serial composer.) Everything in the piece revolves around the soprano narration. The text is from passages in Chapter Eight of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, cut up and rearranged so as to reflect the themes of the book as a whole. The form divides into three “cycles,” flanked by an introduction, two transitions, and a coda. Washerwomen are gossiping at the ford. Cycle I concerns hearsay about Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, Cycle II about his wife Anna Livia Plurabelle. Cycle III depicts the gradual dissolution of the scene into night, with associated intimations of metamorphosis. A generous use of percussion lends atmosphere to the dream-like proceedings.

Liner Notes (Bridge CD 2013)

By Fred Lerdahl

Fred Lerdahl Volume Four

Bridge Records, 2013

In the summers of 1967 and 1968, while a graduate student at Princeton, I had the good fortune to be a resident composer at the Marlboro Music Festival on a grant from the Ford Foundation. Bethany Beardslee, the legendary soprano who devoted herself tirelessly to contemporary music, asked me to compose a vocal work for her. The result was Wake, for soprano, string trio, harp, and percussion (three players). Bethany and a group of Marlboro performers premiered it at the 1968 festival under my baton.

The inspiration for Wake came from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. I arranged the text out of passages from Book I, chapter 8 of the novel, to create the symmetrical formal shape of Introduction, Cycle I, Episode I, Cycle II, Episode II, Cycle III, and Coda. The main action of the piece resides in the cycles, which rise to parallel climaxes and which are meant to reflect the novel’s themes of recurrence and metamorphosis. The harp and percussion clothe the work in a lyrical atmosphere motivated by Joyce’s beautiful language.

Wake was the culmination of my early, post-Schoenbergian style. I wrote it with little system in mind, relying on Joyce’s words to carry my inspiration along. Composing it was exhausting, and after it was finished I went through a long crisis in search of a coherent musical language. Wake contains seeds of my mature musical style in its melodic writing but does not yet show the characteristic formal procedures and harmonic syntax that gradually emerged in works of the 1970s. This marvelous recording, by Bethany Beardslee and the Boston Symphony Chamber Players under the direction of David Epstein, was made originally for a record series funded by the hi-fi company Acoustic Research. The CRI record label later rereleased it on LP and then CD. It is gratifying to have it released yet again by Bridge Records, not only for the sake of the music, but also as a superb representation of Bethany’s distinctive artistry.

Text

Wake

(Arranged from Book I, Chapter 8 of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce)

But toms will till. Will toms till but. Till but toms will.

Tell me all. (Anna was.) Tell me now. The old cheb

went futt, mythed with gleam of her shadda,

holding doomsdag over hunself, dreeing his weird,

queasy quizzers. And the cut of him. And the strut

of him. With a hump of grandeur. For mine ether

duck I thee drake. And by my wildgaze I thee

gander. Saw him shoot swift up her shebba sheath,

like any gay lord salomon, her bulls they were

ruhring, surfed with spree.

Do tell us all about. As we want to hear allabout.

So tellus tellas allabouter. Proxenete.

Where do I stop? Never stop! Garonne, garonne!

Tongue your time now, flow now, ower more.

And pooley pooley.

She was just a young thin pale soft shy (Livia is)

slim slip of a thing then, nymphant shame,

tigris eyes. Of fallen griefs, of weeping willows.

Deep dark, stagnant black pools, innocefree

with her limbs aloft.

Mersey me! Shake it up, do, do!

Calamity electrifies man.

Tell me the trent of it. Onon! Onon!

Close only knows.

Tys Elvenland! The seim anew. (Plurabelle’s

to be.) Look, look, the dusk is growing!

My branches lofty are taking root. What age is at?

It saon is late, ‘tis endless now. It’s churning chill.

Der went is rising. Some here, more no more.

Can’t hear with the waters of. The chittering

waters of. Flittering bats, fieldmice bawk talk.

Can’t hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying

waters of. I feel as old as yonder elm. Dark

hawks hear us. Night! Night! My ho head halls,

I feel as heavy as yonder stone. Night now! Tell

me, tell me, tell me, elm. Night night! Telmetale of

stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of,

hitherandthithering waters of. Night!

Recordings

|

|

Lerdahl: Wake (1968)

Conductor: David Epstein

Musicians: Boston Symphony Chamber Players

Soprano: Bethany Beardslee

LP: Milton Babbitt: Philomel; Fred Lerdahl: Wake. Acoustic Research 0654 083 (1970)

CD: Lerdahl: Waltzes, Eros, Fantasy Etudes, Wake. CRI CD-580 (1990)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

The first appearance of Wake was on vinyl, issued in 1970 as the first LP in the Acoustic Research Contemporary Music Project series from Deutsche Grammophon. Lerdahl’s Wake occupies Side B, with Side A featuring Milton Babbitt’s Philomel, another work written for Bethany Beardslee. In 1990, CRI released an all-Lerdahl compact disc that included the 1970 recording of Wake.

All four works on this disc are original, energetic, and distinctive. Although there are many moments reminiscent of mid-period Schönberg, Lerdahl’s music has more humor and emotion. (Lerdahl embraces dissonance and atonalism, but is not a serial composer.) There’s also a generous amount of colorful percussion.

The first selection is Waltzes, which is not quite what the title leads one to expect. A 21-minute work scored for “low” string quartet (a bass replacing the second violin), it’s composed of twelve “virtuoso” waltzes that run together without pause, and sounds more like a string quartet than a series of elegant dances. These “waltzes” are indeed virtuoso pieces, ranging from moments of quiet beauty to passages of dissonance that bring to mind Shostakovich. They’re filled with energy, passion, and moments of mercurial humor; quotations are made and distorted, there are sudden shifts in direction, and momentum gradually builds until the fugal climax.

The second track is Eros, my favorite work on the disc, a 22-minute sequence of variations on Ezra Pound’s poem “Coitus”:

The gilded phaloi of the crocuses

are thrusting at the spring air.

Here is there naught of dead gods

But a procession of festival,

A procession, Giulio Romano,

Fit for your spirit to dwell in.

Dione, your nights are upon us.

The dew is upon the leaf.

The night about us is restless.

Scored for mezzo-soprano, flute, viola, harp, piano, percussion, electric guitar and electric bass guitar, Eros is difficult to describe—the Grateful Dead performing Erwartung was one of my first impressions, an opera involving an alien mating ritual was another. (Though tongue-in-cheek, these comparisons suggest the general flavor of the piece!) The music evolves slowly, and moods shift with disarming subtlety—Eros is at times eerie, chilling, gorgeous, even shrill; but always fascinating. The veiled sexuality of the lyrics coupled with the strangeness of the score gives Eros an otherworldly sensuality, a delicious sense of being seduced and devoured. The flute haunts and teases, the guitars rain down notes from outer space, and the percussion suggests scenes from some barbaric ritual. Only the strings and harp offer moments of tranquility, and even those are suffused with unease.

The Fantasy Etudes are the quietest works on the disc, twelve interlocking and overlapping pieces scored for a “Pierrot-like ensemble,” each growing more complex until collapsing “under the weight of its own elaborations,” subsequently giving birth to the next etude. Like all of Lerdahl’s work, the Fantasy Etudes are complex and endlessly intriguing.

The disc ends with Wake, which has already been reviewed above. Although this CD has been sadly deleted, you can still obtain used copies or download a digital version of the album on lossless FLAC. Highly recommended!

Lerdahl: Wake (1968)

Conductor: David Epstein

Musicians: Boston Symphony Chamber Players

Soprano: Bethany Beardslee

CD: Fred Lerdahl, Volume Four. Bridge Records 9391 (2013)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

In 2013 Bridge Records reissued the 1970 recording of Wake as part of their 7-volume “Fred Lerdahl” series.

Notes

But there’s also an objective difficulty in verbalizing musical experience, so that the non-specialist in particular must have continual recourse to metaphor.

—Luciano Berio, “Two Interviews” (1981)

Back in 1997 when I first added Lerdahl’s Wake to the Brazen Head, I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it! I was a younger man then, having only recently discovered the atonal pleasures of twentieth-century music, and lacking the necessary vocabulary to write about a piece like Wake even using the typical metaphors, sensual impressions, and comparisons that “non-specialists” like myself employ when describing music. But I did think I was clever. So I produced a kind of half-assed story to describe the music without actually doing the work of describing the music. In honor of my younger self—and all his prolix attempts to be “clever”—I present my original 1997 “review” of Wake below. I should also mention that I practically worshipped John Cage at the time…

Fred Lerdahl’s Wake

This wonderful piece is a bit hard to describe; but I have a few thoughts on how Lerdahl might have been inspired….

See, John Cage, upon ascending to Heaven, looked up Arnold Schönberg, who, being slightly peeved at God for not lending him a hand with Act 3 of Moses und Aron, was revising it so the Golden Calf came out ahead. Cage coughs politely. “Arnie,” he says, “I really like that Pierrot Lunaire thing you did. Great stuff. I was just wondering, have you read this book?” Cage thrusts a battered copy of Finnegans Wake into his hands. Schönberg eyes it warily. Cage continues, “Well, there’s this Fred guy down on Earth, nice boy, very creative, and he really wants to write a new piece for this soprano he admires; but it’s got to be a bit unusual—something to spook the old folks, but still, you know, engaging.”

Schoenberg raises an eyebrow.

Cage presses on, “She has a great voice, and the whole piece should unfold around her narrative. The music needs to be nervous, edgy, some of that atonal stuff that really keeps you on your toes, but not cold or overly dissonant.” Cage surreptitiously nudges the score of Pierrot Lunaire so it covers his friend’s later, purely serial works. “You remember her, right? Cathy Beardslee? You liked her a lot in Pierrot. But here she’ll sing in English. Well, sort of.”

At which Schönberg finally speaks: “I don’t know, John. Will there be Sprechstimme?”

Cage waves his hand, “Sure, a bit, but also some clear flights of lyrical beauty, some whispering, maybe a shout or two. The music will be fun, but complex. And, yeah—percussion. There’s gonna be some real percussion here. It’ll follow a cyclical motif, and the music will be as varied as the singing and the text. And silences, yes. We’ll need a few quiet moments and some lovely silences. So, can you send this Fred fellow some inspiration?” Cage playful winks and punches Schönberg in the arm.

Schönberg frowns for a second, then asks, “Silences?” Cage nods, and Schönberg reluctantly opens the Wake. After a few puzzled moments, he closes the book and says quietly, “You know, Alban and Anton are right down the hall….”

Well, that’s how I picture it, anyway. And the fact that Cage died twenty-four years after Lerdahl’s Wake was written, well, I’m sure you’re all far too charmed by the story to point that out, right?

Additional Information

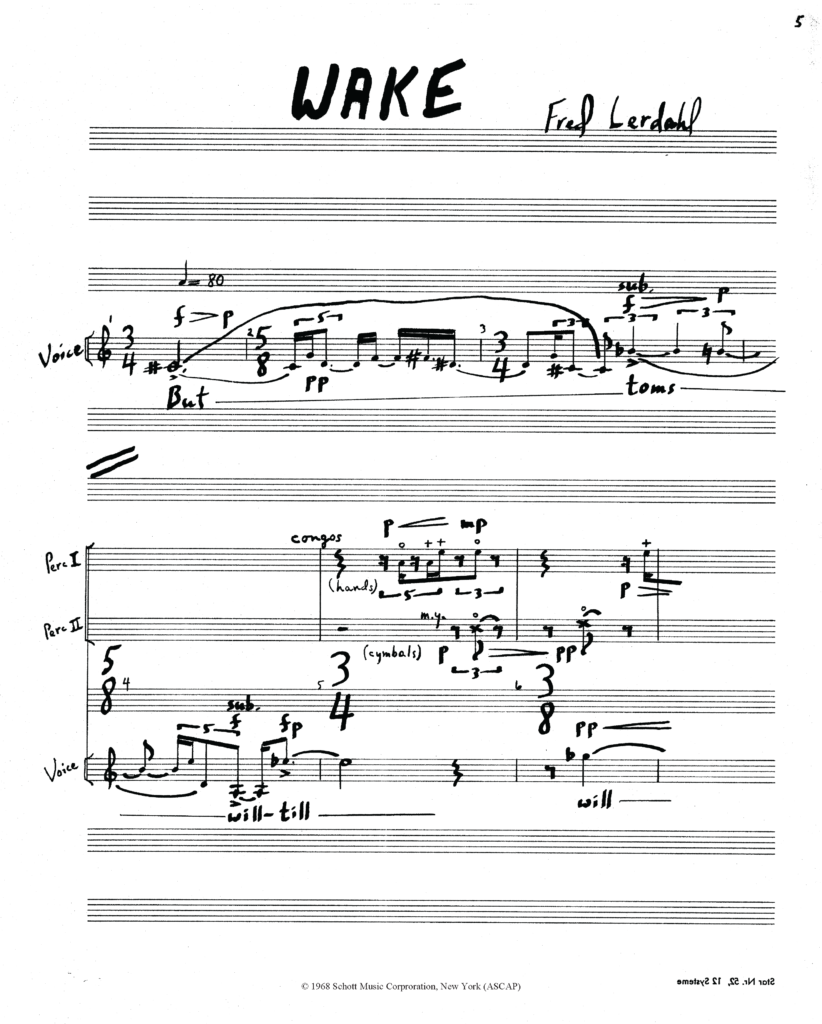

Wake Score

The score for Wake was published by Schott Music. You can browse selected pages here, too.

Fred Lerdahl Homepage

The composer’s homepage contains a biography and a detailed listing of his works and recordings.

Fred Lerdahl Interview

On 16 May 1992, the tireless Bruce Duffie interviewed Fred Lerdahl for WNIB.

Bethany Beardslee Interview

On 18 June 1995, Bruce Duffie interviewed Bethany Beardslee for WNIB.

Schönberg: Pierrot Lunaire (Beardslee Recording)

You can listen to Beardlsee’s wonderful recording of Pierrot Lunaire on YouTube.

Pierrot Lunaire Text

You can read the original French text of Pierre Lunaire, along with Otto Erich Hartleben’s German translation used by Schönberg and Brian Cohen’s English translation. [PDF]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 30 August 2024

Return to: Fred Lerdahl Page

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com