Joyce Music – Berio: Traces

- At August 01, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

God sent the plague,

the God who takes off our masks.

—Edoardo Sanguineti, “Tracce,” 1964

Tracce/Traces

(1961-1964)

For soprano and mezzo-soprano soloists, two actors, two choruses of 24 voices each, and orchestra.

Duo Becomes Traccie

Withdrawn in 1972 and never recorded, Traces is a piece of musical theater that passed through several iterations, each displacing it farther from its original source of inspiration—the “Circe” episode from James Joyce’s Ulysses. Most of what’s known about Berio’s so-called “ghost opera” comes from the research of musicologists Tiffany Kuo and Angela Ida De Benedictis. In a piece published in Le théâtre musical de Luciano Berio, De Benedictis explains the Joycean roots of Traces:

One of the initial ideas for Traces, or rather, an element that will flow into it, is nevertheless indicated in an embryonic form [that] leads back to the early stages of [Berio’s] ideas on Passaggio. In a letter to Alfred Schlee (of Universal Edition) of January 12, 1961, in fact, Berio mentions to his publisher three theatrical projects on which he is simultaneously working, entitled respectively Passaggio, Duo and Opera aperta. In the lines dedicated to the second project, Duo, one of the central themes developed in Traces is clearly recognized: “It is the story of an encounter between a boy and an old man (a door man of a night club), in the night […].” As the composer explains in the same letter, the idea of this work comes—once again—from Ulysses by Joyce and, to be precise, from the end of the 15th chapter, “Circe,” when Bloom, having left the brothel, has a vision of his son Rudy, who died just days after being born. That this suggestion, which first arose in 1961, was carried forward until 1964 is partially confirmed by a provisional title found in the typewritten drafts of Traces, where Berio suggests “Traces x Ulysses?”

In May 1961, Berio received a commission from the Koussevitzky Foundation “in recognition of Berio’s contributions to the music literature of our time.” The grant committee requested a piece for chamber ensemble, and the autograph manuscript would be enshrined in the Library of Congress. This was followed a year later by an invitation from the Venetian Biennale. They wanted another “theatrical piece” like Allez-Hop from 1959. Berio was still working on Passaggio, his first collaboration with Italian poet and Dante scholar Edoardo Sanguineti. He informed Venice they could have his next “lavoro di teatro,” which was tentatively named Traccie. (Berio’s letter is the only time this spelling occurs; afterwards it’s just referred to as Tracce, or “Traces.”)

Tracce Becomes Esposizione

As the Venetian project came into focus, Berio replaced the name Tracce with Esposizione, or “Exhibition.” A collaboration between Berio, Sanguineti, and Ann Halprin, the avant-garde choreographer, the piece was scored for mezzo-soprano, two children’ voices, four-track tape, orchestra, and dancers. Cathy Berberian naturally sang mezzo, and the dancers were supplied from Halprin’s Dancers’ Workshop of San Francisco. A bizarre critique of consumerism, the choreography included the dancers lugging various commercialized objects up a cargo net suspended above the stage and audience. Sanguineti’s libretto combined catalogues derived from Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae, lists of popular entertainments, and quotations from Arthur Rimbaud, Edgar Allan Poe, and Sanguineti’s own Laborintus. The conclusion simulated the collapse of the net upon the unsuspecting audience—whom should have been prepared for this, as they’d already been bombarded by tennis balls!

Tracce (A Slight Return)

Berio withdrew Esposizione after its first and only performance and turned his attention to Washington—perhaps the Library of Congress would like a small opera instead of a chamber ensemble?

Resurrecting the name Tracce, Berio expanded his idea for Duo into an experimental opera involving paired actors, soloists, and choirs. In the hands of librettist Edoardo Sanguineti, these pairs became ideological opposites inhabiting a “metaphysical atmosphere”—a vague, fiery Apocalypse ostensibly delivered by a wrathful God. Leopold Bloom and Rudy were alchemized into generic archetypes played by actors: the Boy (Ragazzo), and the Old Man (Vecchio). Like a couple misplaced from some Beckettian netherworld, the pair are forced into cooperation as they cross the nightmare landscape. Meanwhile, the chorus and a pair of female soloists offer commentary on the divided world. Beginning as a unified group, the chorus splits into hostile factions, one group donning black masks and the other white masks. Representing polarized opposites—racial, political, religious, etc.—these choirs assume positions “like the spirits of a cemetery garden.” The libretto calls for much speaking, singing, shouting, sprechstimme, and haranguing; at one point an M.C. reads hateful epithets over a microphone accompanied by a laugh track. Shakespeare is quoted frequently, particularly Hamlet. The work reaches its dramatic climax when the choirs “rush towards each other theatrically” in a simulated riot.

Edoardo Sanguineti in 1963 (Photo by Mario Dondero)

Edoardo Sanguineti in 1963 (Photo by Mario Dondero)

An overview of Sanguineti’s intentions may be gathered from this description by Tiffany Kuo:

[It] is clear that Traces was conceived by Sanguineti in the style of experimental theater, its cast comprised of unoriginal stereotypes organized in pairs of diametric opposites: two types of chorus (“un oratorio” and “una cantata,” speaking versus singing), two types of actors (“un ragazzo” and “un vecchio,” young versus old), and two types of female vocal ranges (a soprano and a mezzo-soprano, high versus low).

Even the actions and texts are configured into contrasting elements. The spoken words, as implied in the scenario, are at times simple and direct, like “a cantare i versi didascalici,” and at other times, they are incomprehensibly tangled, jumbled, and chaotic, such as a multi-layered drama with laugh track, a soloist sight-reading a text from a script, one chorus “parlano tra loro” interrupting each other, while the other chorus alternates with singing as if an “opera da concerto (…) con gesti melodramatici,” and speaking in simple, plain speech, “parlato vero.”

Tracce Becomes Traces

While Sanguineti was busy in Italy and the Library of Congress remained happily oblivious in DC, Berio was undergoing a few profound life changes. In 1962 he began teaching Darius Milhaud’s classes at Mills University in California. There he began a romantic relationship with a psychology student, Susan Oyama. As his stay in the United States lengthened, Berio became increasingly aware of America’s toxic blend of racism and economic disparity. (Mills University was in Oakland, which has a long history of racial tensions. There’s a reason the Black Panther Party was founded here in 1966, and Sun Ra picked Oakland to declare “Space Is the Place.”) Berio began reading James Baldwin—The Fire Next Time was particularly inspirational—and became interested in African-American spiritual music and dance, attending services at the Shiloh Pentecostal Church in West Oakland.

Berio began to see “Traces” as a distinctly American piece, and turned to his new love, Susan Oyama, for creative input. Signaling to Sanguineti that he’d be sharing credit for the libretto, Berio increasingly relied on Oyama to “translate” Sanguineti’s European ideas into a modern American idiom. The theatrics of the piece were radically altered—rather than being symbolically differentiated by masks, the performers would be literally specified by race. And if one couldn’t find enough African-American performers, there was always blackface. As Berio wrote in his introduction to the final score of Traces:

This piece should ideally be presented by Negro performers, the only exception being the mezzo-soprano, who should be white. Chorus A should be casually dressed. Rather formally attired, Chorus B should wear white masks which allow easy vision and leave the mouth free. The Negro soprano is to be dressed simply; the mezzo-soprano in a revealing evening gown. The two actors may wear whatever the director prefers.

Should the use of Negro performers not be appropriate or possible, another racial group of comparable status may be substituted. If this cannot be done, white performers may be used, Chorus A, the soprano and the actors in black make up and Chorus B and the mezzo-soprano in costumes of Western civilization from 1492 to the present. In the case that racial opposition should not be pertinent to the community for which the piece is to be presented, any locally significant social, political or economic groups may be used, provided these groups present a meaningful opposition and can be represented on the stage. At any rate, Chorus B should function as an unflattering mirror to the audience; an all-Negro audience, for instance, might see Chorus B in black masks…

Yes, of course, what could go wrong?

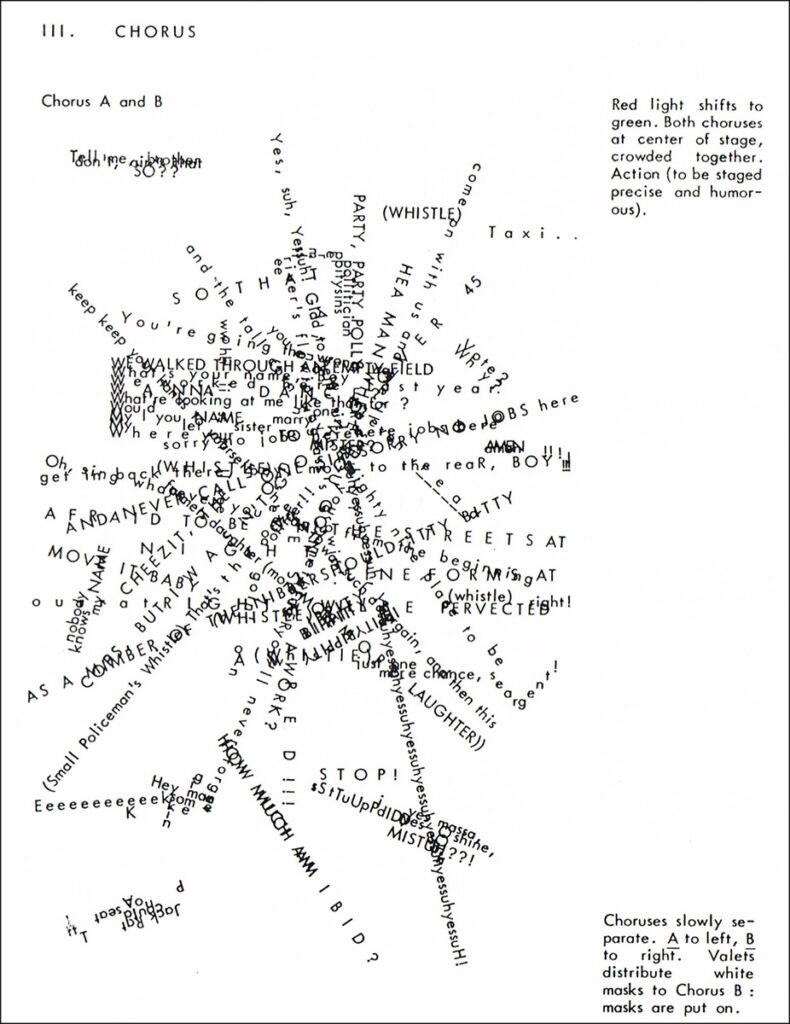

Oyama’s completed libretto maintained little of Sanguineti’s original text, and was permeated by 1960s black slang (“Hey, man, gimme some skin!”) and ironic callbacks to minstrelsy (“Yes massa, yes suh!”). Choral parts were arranged in difficult-to-read constellations, which invited a degree of indeterminacy.

Page from “Traces” Libretto (From De Benedictis)

Page from “Traces” Libretto (From De Benedictis)

Edoardo Sanguineti was less than pleased by Oyama’s changes, claiming the new libretto “no longer has anything to do with my text,” and demanding—in all caps!—to “TAKE OFF MY NAME!” Berio apologized, and offered an olive branch in the form of a new commission: Radiodiffusion Télévision Française wanted a piece to commemorate Dante’s 700th birthday, and Berio knew just the man to write the libretto! That commission would come to fruition in 1965 as Laborintus II, one of Berio’s most enduring collaborations with Sanguineti. Scored for three female voices, eight actors, one speaker, orchestra, and tape effects, Laborintus II incorporated fragments from the recently-withdrawn Esposizione.

In the autumn of 1964, Berio and Oyama left Mills for Harvard. Berio taught a semester of music while Oyama pursued her doctoral research. Berio and Berberian were divorced, and Berio and Oyama were married a year later.

Traces Becomes a Disaster

The première of Traces was scheduled for the Library of Congress in the autumn of 1964. After receiving the libretto, Harold Spivacke, the Chief of the Music Division and the overseer of the Koussevitzky grant, informed Berio the piece could not be performed: “I must confess that the English text strikes me as wholly unsuitable for performance at the Library of Congress particularly because of the vulgarities and obscenities which it includes as well as certain other passages which would certainly give offense.” Berio attempted to stage the work elsewhere in the U.S., but to no avail. In 1968 Traces was scheduled to be performed in Paris. French irony intervened, and the production was cancelled because of real-life riots. A frustrated Berio explained to an Italian newspaper, “[Traces] has always been boycotted and prohibited in America….Unfortunately racial discrimination, which is a source of tragedy in American life, such as the war in Vietnam, has always prevented its execution.” While Berio was correct about America’s shameful history of racism, the Italian composer remained oblivious to other factors which may have prevented the staging of Traces, even among American performers with progressive ideals. In any event, he was about to find out.

The only performance of Berio’s Traces occurred the afternoon of 9 May 1969 at the Center for New Music at the University of Iowa. Despite the CNM’s avant-garde credentials, things did not go well. According to University historian Barbara C. Phillips-Farley:

The May concert was the final one of the season for the CNM, and it featured the Crumb piece and the first performance of Luciano Berio’s Traces. [Professor Richard] Hervig said:

The biggest disaster was the first performance of Berio’s Traces.

Traces was very difficult to rehearse, because the notation was vague. Furthermore, the composer wanted the performers to act and to simulate a race-riot in the middle of the piece—it was supposed to address the black-white problem in the United States. This made the performers uncomfortable. Hervig and [Donald Martin] Jenni recalled:

[Berio] really felt that we should have half the chorus in blackface…. It was just a total disaster.

One of the things I remember very strongly was a performance that I finally didn’t do—I went to all the rehearsals and got sort of “bummed out.” That was Berio’s Traces… The notation was very sloppy and had lots of signs that were unexplained. There wasn’t one explanatory note in the score; so we just had to fake it… I thought, “Well, maybe not: I think I’ll just sing and play the piano in something else.”

But even with the unsuccessful performance of his piece, he did enjoy his stay in Iowa City. Hervig explained:

After the performance, he and his librettist came out to our place—it was an afternoon performance—and Verna hadn’t expected this, so she made grilled peanut butter sandwiches! He loved them; he ate half-a-dozen. I played “Blood, Sweat, and Tears” for them, and he loved it. He loves American jazz. And we drank whiskey. He’s a wonderful guy.

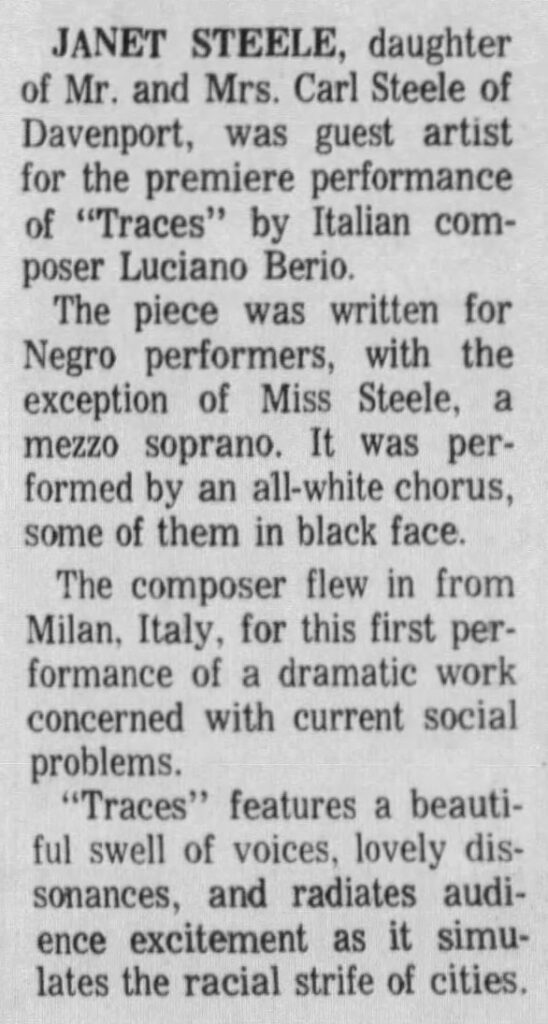

On the other hand, at least one person enjoyed the première—Janet Steele, who played the part originally intended for Cathy Berberian:

Quad City Times-Democrat, 10 May 1969

Quad City Times-Democrat, 10 May 1969

Traces Becomes Opera

No additional performances of Traces were forthcoming in the United States or Europe. In 1970 Berio incorporated some of the music from Traces into the “number” that ends the first act of Opera, his postmodern meditation on Monteverdi, the Titanic, and terminal illness. In 1972—the same year he divorced Oyama and returned to Italy—Berio formally withdrew the score of Traces from Universal Edition.

Postscript: O King

The tortured political landscape of 60s America did provoke one masterpiece from Berio—O King, a tribute to the slain Civil Rights leader, composed in 1967 for mezzo-soprano and five instruments. A haunting work that finds beauty in disquietude, O King dissembles Martin Luther King’s name into disjointed phonemes, ghostly pitches that snap into focus at the very end. A year later, Berio expanded O King to a full orchestra and made it the second movement of his great Sinfonia.

Sources and Notes

Visitors interested in Traces are encouraged to read Tiffany Kuo’s original research into the piece, “An Americanization of Berio,” and Angela De Benedictis’ thorough investigation, “From Esposizione to Laborintus II.” I am greatly indebted to De Benedictis for her research, which contains Berio and Sanguineti’s letters, Sanguineti’s original notes, and excerpts from Oyama’s libretto, which is every bit as cringeworthy as it sounds.

“Would you let your sister marry one?”

“Would you let your sister marry one?”

To be honest, it’s probably best Traces was withdrawn. Black slang written by a Japanese-American psychology student? An American race riot musically choreographed by an Italian composer? A recommendation that if no Negroes are available, white singers should wear blackface? It sounds like something from South Park! While Berio and Oyama’s hearts were in the right place, even for the 60s it’s a bit much. I’m the last person who thinks that artists should “stay in their lane,” but not everyone can pull off a West Side Story! (Even Frank Zappa had his unfortunate Thing-Fish.)

What I find especially frustrating is what “could have been.” Sanguineti’s original libretto is kind of amazing, a surreal parody of political antipathy, religious mania, and Beckettian perseverance. If Berio would have stuck to his original partner’s Circe-like vision of an ideological black mass, Tracce might be more than an embarrassing footnote in Berio’s remarkable oeuvre.

Text

I have little desire to reprint Oyama’s libretto, which is best collecting dust in the Library of Congress. However, Sanguineti’s Tracce is another matter! The following is an English translation of Sanguineti’s working draft. Mailed to Berio in 1964, the libretto was reprinted in De Benedictis’ paper as Appendix 4c. I translated it from the Italian using Google Translate, then made edits using my rudimentary understanding of Italian. (In other words, I’m no William Weaver.) Unfortunately Sanguineti’s poetic spacing cannot be replicated in WordPress—the real thing is much prettier.

Tracce

1) Dialogue II (Ragazzo e Vecchio)

—take me away, boy.

—where do you want to go?

—in a place full of light.

— there’s a distant light, see?

—let’s go there, accompany me.

—we have to cross the river.

—we cross the river.

—we have to cross the mountain.

—we cross the mountain.

—we have to go through the fire.

—fire? fire? again, the fire?

2) Dialogue III (Ragazzo e Vecchio)

—it’s night, and I’m tired.

—we cannot stop:

you have to walk again;

lean on me!

—I’m old, boy:

it’s late, its late!

—where do you put your feet? look!

you walk over the graves!

—I’m slipping!

I go down! I fall!

help me!

—there is water here.

—I burn! it’s fire!

—now, the fire! you see:

now, and again!

again, fire!

3) Spoken part at the microphone: Soloist and Choir

S—and God sent the plague!

C—the plague!

S—and the fire:

fire over the city!

C—and the fire!

and God sent fire!

S—sent angels of fire:

he sent his white angels.

C—and God sent the plague:

the black plague and the black fire!

the black fire and its white angels!

S—who sees the white angels,

her eyes are closed forever: too much light inside her eyes,

and no one can resist.

C—we saw the white angels:

our eyes, God, are closed forever, forever!

S—pray to the Lord of angels pray to the white Lord!

God sent the plague,

the God who takes off our masks.

C—I live in a land of white angels, and I want to pray to God:

S—to open my eyes forever, to tear off my black mask!

4) Mask changing chorus

—tear off your mask, beast!

—tear off your face!

—skin!

—who is cursed?

—you can’t recognize me!

—look at yourself in this mirror!

—recognize each other!

—look into my eyes!

—are you this or this? or this?

—mask!

—confess!

—rotten blood!

—recognize me!

—you are color, not man!

—you are colour, and only colour!

—black cock!

—I’ll take your skin, look!

—this is my place!

—I hate you! I hate you!

—get away!

—everything is confused!

—good and evil are confused!

—what a night!

—peace!

—clean yourself!

—dirty bull!

—shit!

—your face, to me!

—fascists!

—breed of pigs!

—black pigs!

—race!

—down the mask! street!

—how they stink!

—once and for all!

—hang them all!

—silence!

—black whore!

—you are evil, sin!

—okay!

—cursed race!

—everyone away!

—silence!

—who I am? who are you?

—democracy! democracy!

—out of here! street!

—communists!

5) Initial part of B: only anagrams; short self-generations

oh! who wants heaven?

and everywhere: graves; and: look:

where do you put them? (the feet): look!;

look down! below!

who sings? who keeps singing? too loud guys! hold still!

oh! oh! oh! hold still, please! you are too quick; let me take a breath:

oh! you guys are pigs! watch out! you always want to have fun, huh? well, all right, well:

they closed the gates—it’s cold; stay with me; I get pneumonia; this

dirty fog: it comes up from the river, always:

it’s that I’m a little tired, though; but yes, a little tired:

go away, now: it’s already night: I want to be alone, put my feet in the water:

look: my tongue is dirty, and a wound in the gum, here: and then:

close my eyes with your hands; oh, no: I said: the eyes (I said): I want to sleep, now: open the window:

no, it’s not this:

the wind is blowing: fffff.

Additional Information

“An Americanization of Berio: Tracing American Influences in Luciano Berio’s Traces”

By Tiffany Kuo, from Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher Stiftung, Nr. 22, April 2009. Tiffany Kuo is Chair of Music at Mt. San Antonio College, and specializes in the relationship between public funding and music in post-World War II America. She was also the fact-checker for Alex Ross’ essential book on twentieth-century music, The Rest is Noise. Her brief paper on Traces discusses the changes Berio and Oyama made to “Americanize” the libretto. It’s available as a free PDF download.

“From Esposizione to Laborintus II: Transitions and Mutations of a ‘Desire for Theatre’”

By Angela Ida De Benedictis, from Le théâtre musical de Luciano Berio, 2016. A musicologist who specializes in twentieth-century Italian composers, De Benedictis served as Scientific Director of the Centro Studi Luciano Berio. This thoroughly researched paper was my primary source of information on Traces. While some of the Italian need to be passed through Google Translate, it’s worth reading for anyone interested in Berio’s collaborations with Sanguineti. It’s available as a free PDF download.

Luciano Berio: Other Joyce-Related Works

Luciano Berio Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Luciano Berio profile.

Chamber Music (1953)

Three songs adapted from Joyce’s poetry.

Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958)

An electronic transformation of the opening text from the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses read by Cathy Berberian.

Epifanie (1961/65)

A variable sequence of orchestral and vocal pieces, including texts from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.

Sinfonia (1968/69)

This tour de force of music, voice, and sound incorporates text from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable. While it has no overt Joycean references, Sinfonia is frequently compared to Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

A-Ronne (1974/75)

A “documentary” on a poem by Edoardo Sanguineti, this piece of vocal virtuosity contains a reference to Finnegans Wake.

Outis (1996)

Berio’s opera about the transformations of Odysseus includes material borrowed from Joyce’s Ulysses.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 4 February 2023

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com