Joyce Music – Berio: Thema (Omaggio a Joyce)

- At November 26, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Poetry is also a verbal message distributed over time: recording and the means of electronic music in general give us a real and concrete idea of it, much more than a public and theatrical reading of verse can.

—Luciano Berio, “Poetry and Music,” 1959

Thema (Omaggio a Joyce)

(1958)

For two-track tape

And a call, pure, long and throbbing

In 1952, Berio heard his first piece of electronic music at a concert in New York City: Sonic Contours by Otto Luening and Vladimir Ussachevsky. Although he considered the piece “rudimentary,” he was intrigued by the technology. Returning to Milan, he began working at RAI, the Italian version of the BBC. He used his position to experiment with new music, often in collaboration with his friend and fellow composer, Bruno Maderna. In 1955, Berio and Maderna opened the Studio di Fonologia Musicale di Milan. Affiliated with RAI, the Studio di Fonologia soon became a center for electronic music, attracting such visiting composers as Henri Pousseur and John Cage.

That same year Luciano Berio met Umberto Eco. A recent graduate of the University of Turin, the young philosopher had accepted a position at RAI producing cultural programming for Italian radio and TV. Eco became fascinated with the work of Berio and his compatriots such as Boulez, Stockhausen, and Pousseur, absorbing the 1950s musical avant-garde into his developing theories of the opera aperta, or “open work.” A core tenet of postmodernism, an “open work” is written, designed, or composed in a way that invites multiple interpretations, an act which deliberately involves the audience (and/or performer) in the creative process. Eco’s work would eventually be transformed into his first major book, Opera aperta, published in 1962.

Soft word. But look! The bright stars fade

The writer most central to Eco’s research was James Joyce, particularly Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. Berio had been familiar with Joyce from his student days—after all, he set three of Joyce’s poems in Chamber Music in 1953. But it was Umberto Eco who first introduced Berio to Joyce’s revolutionary novels, and the composer became fascinated with Joyce’s complicated narrative structures and wordplay.

This fascination coincided with two other of Berio’s developing interests. The first was electronic music; or more specifically, tape manipulations, electronic processing, and electroacoustic transformations. The second was the human voice. Having recently married Cathy Berberian, one of the most versatile and adventurous sopranos of the twentieth century, Berio wanted to push the envelope of vocal writing. Not just virtuoso singing; but what the human voice could actually do, what it could become.

Cathy Berberian, the Voice of Berio

Cathy Berberian, the Voice of Berio

Berio’s first attempt to merge this constellation of interests centered on a proposed radio program developed with Eco, a musical exploration of poetic onomatopoeia. The first subject would be the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses. Joyce’s bravura attempt to render music into language, he once claimed the challenging episode reflected a fuga per canonen, a repetitive musical structure in which fragmented pieces are allowed to overlap. This claim has generated a certain amount of controversy among musically-inclined Joyceans, who have combed through “Sirens” searching for every musical correspondence, allusion, and illusion. Some claim to have found this hidden structure, others believe Joyce may have misunderstood the term, while some think your man was just taking the piss.

Berio took Joyce’s statement as a metaphor, but saw that metaphor as a point of departure for a musical experiment. Working with Eco, he recorded passages from “Sirens” in three languages—English, Italian, and French. These recordings were superimposed on each other to form clusters of consonance. As Berio remarked in a later interview, the “onomatopoeic sections overlapped. At such places tension grew to the point of explosion.” The composite recording was subjected to electronic manipulation, but Berio was unhappy with the results, and the piece was never aired.

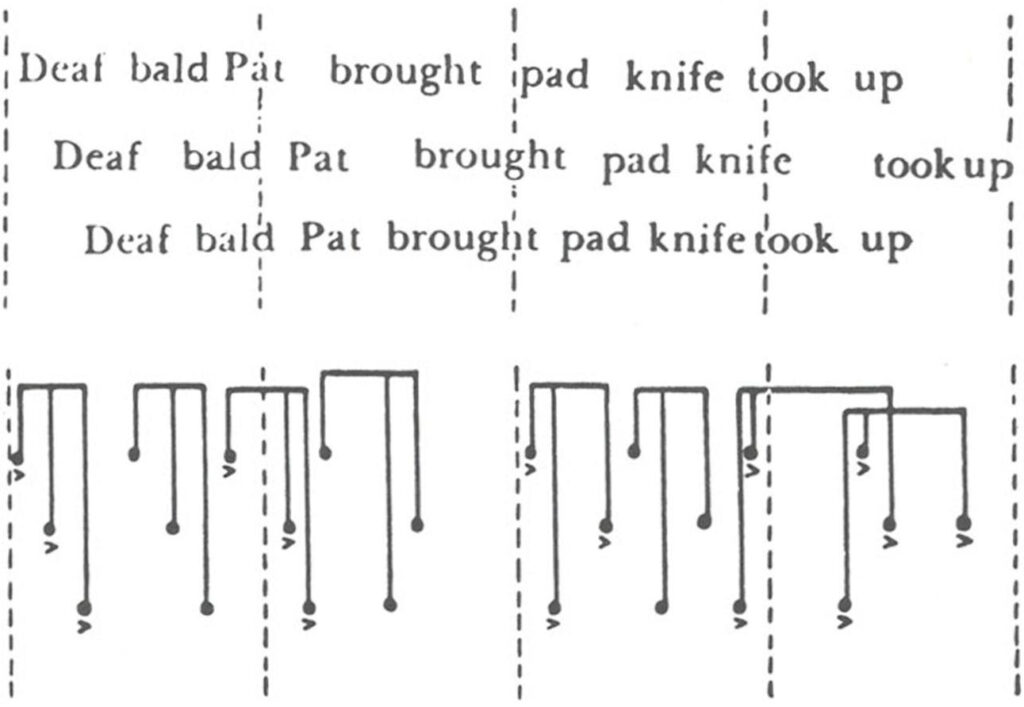

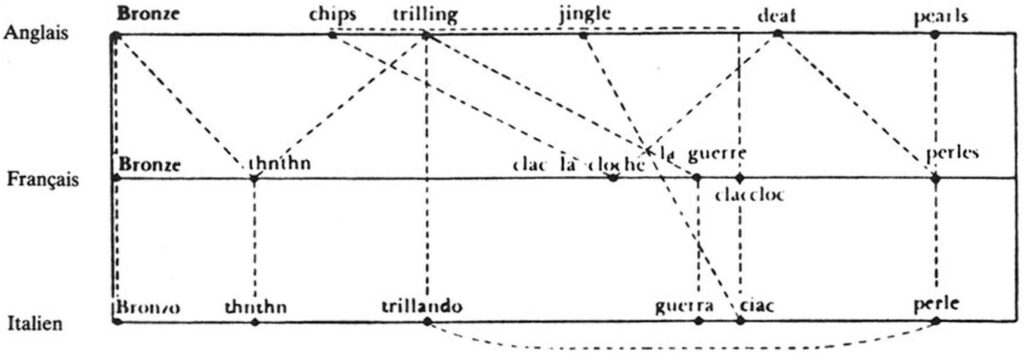

Berio’s first attempt at “Thema.” From “Contrechamps”

Berio’s first attempt at “Thema.” From “Contrechamps”

Bronze by Gold

Returning to the drawing board, Berio reduced the scope of the project. He narrowed his focus to Joyce’s original text, the first page of the famous “overture” read by Cathy Berberian. After a full playthrough of her unaltered reading, the passage is recycled, now subjected to a battery of electronic manipulations—words are atomized into syllables and recombined, sounds are stretched or compressed, single utterances are multiplied into choral starbursts. Called Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), the 8-minute tape sounds like an answering machine gone haywire, transforming its message into a bizarre new medium. This McLuhanesque transformation is Berio’s entire point, a demolishing of traditional barriers “between word and sound, and between sound and noise; or between poetry and prose, and between poetry and music.”

Since its “première” in Naples in 1958, Thema has achieved the status of an electronic classic. One of Berio’s most-discussed pieces, the influence of Thema is felt on everything from Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain to the Beatles’ “Revolution 9.” Berio followed Thema with even more ambitious vocal deconstructions, including electronic pieces such as Visage, and more “traditional” works such as A-Ronne, Sequenza III for woman’s voice, and Recital I (For Cathy), a record of a singer’s nervous breakdown.

Notes on “Thema.” From “Contrechamps”

Listen!

Having recognized its historical importance, it seems only fair to note that like most mid-century electronic music, Thema sounds quite dated to modern ears. Three-plus generations of sampling and digital processing have made experiments like Thema feel quaint, relics from a bygone era of humming oscillators and reel-to-reel tape.

That isn’t to say Thema can’t be enjoyed, especially when approached with the right mindset! It’s best to imagine how it might have sounded to contemporary ears. Just relax and cast your mind back…Eisenhower is in the White House, “Volare” is the number one song crooning from transistor radios, and Aaron Copland is considered America’s greatest contribution to classical music. Maybe you’re a young Don Draper, looking quizzically at the new LP your Beatnik girlfriend loaned you. You slide it from the paper sleeve and carefully place it on your hi-fi. The needle drops, and suddenly there’s some platinum-haired chick reading beat poetry from that dirty book everyone’s talking about. And then….ssssssss, whreeee, boom!

You know what’s next. You trade that book of Cheever stories your boss loaned you and start reading The Recognitions. Boy those parties sure sound fun! You let your hair get just a bit shaggy; maybe start hanging out with Benny Profane and listening to McClintic Sphere. Soon you’re playing Stockhausen albums at The Scope and arguing with the Yoyodyne guys that “Revolution 9” just demands repeated listening. Then it’s on to Ummagumma, and you know you’re the first one to buy a Wendy Carlos album. And then, boom! Suddenly it’s the 1980s, and even Herbie Hancock’s got Future Shock. But you were always there, baby: Clapclop. Clipclap. Clappyclap!

Ok, so maybe taking a 15-mg gummy may help with this little experiment. But even if you find yourself unimpressed by the hissing, whirring, and gobbling of Berio’s electronic transformations, there’s always Cathy Berberian, whose brilliant reading of “Sirens” is like a joyous, barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world. Somewhere in that great Library of Might-Have-Beens there’s a 1959 Caedmon LP of sweet Cathy reading the entire chapter…

Liner Notes from BMG’s Many More Voices

By Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio: Many More Voices

BMG, 1998

For me, the significance of electronic music lies not so much in the discovery of “new sounds,” but more in the unique opportunity to enlarge the domain of sound phenomena and to integrate them into a musical thought that justifies and provokes further extensions. It is within this perspective that Thema (Omaggio a Jovce), composed at the Studio di Fonologia of the Italian Radio in Milan in 1958, should be understood.

In Thema, I attempted to present a musical reinterpretation of a reading of a text from Ulysses by James Joyce, by developing the polyphonic design that characterizes the eleventh chapter (entitled “Sirens” and dedicated to music), whose narrative technique suggests a reference to polyphonic music and to Fuga per canonem in particular. Thema is not based on electronically produced sounds but solely on the voice of Cathy Berberian reading the opening of this chapter. In this work, I was interested in developing new criteria of continuity between spoken language and music and in establishing continual metamorphoses of one into the other. By selecting and reorganizing the phonetic and semantic elements of Joyce’s text, Mister Bloom’s day in Dublin momentarily follows an unexpected direction, in which it is no longer possible to make distinctions between word and sound, and between sound and noise; or between poetry and prose, and between poetry and music. We are thus forced to recognize the relative nature of these distinctions, and the expressive characters of their changing functions.

Excerpt from Two Interviews

By Luciano Berio & Bálint András Varga

Two Interviews

Marion Boyars, 1985

Varga: The friendship of Edoardo Sanguineti and Umberto Eco, the influence of their ideas and works have considerably affected your own composition over more than two and a half decades.

Berio: Yes, both of them have played an important role in my life. I met Eco in Milan in the mid-fifties. We soon discovered that we took a similar interest in poetry and within it, onomatopoeia: I introduced him to linguistics and he introduced me to Joyce.

Without Eco Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) wouldn’t exist. Both of us were fascinated by onomatopoeia in poetry and after having gone through Italian literature, we addressed ourselves to Joyce. The eleventh chapter of Ulysses is a triumph of onomatopoeia. Joyce employs a different technique in each chapter and since this one is devoted to music, his musical reference is the fuga per canonem. This is of course impossible to realize with a written text, in the original sense of the term: it is a kind of generalized metaphor. But even so there is a subject, a counter-subject, a development, there are stretti—and different performing techniques, too, such as trills, glissandi, and so on. We only concentrated on the beginning of the chapter (the exposition of the fugue), up to the “cadenza” where everything becomes saturated by s, a kind of cadence of white noise. We then compared the sound of the English text with those of the French and Italian translations.

V: Why do that?

B: Poetry has always looked at music nostalgically—as though at an unattainable possibility. The associative mechanism of poetry tends to suppress the musical character of its sound. I was interested in how to bridge the distance between poetry and music.

Eco and I copied the English, French and Italian readings of Ulysses so that the onomatopoeic sections overlapped. At such places tension grew to the point of explosion.

That kind of research was gradually replaced by music. The aim of Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) was to create a genuine composition by making use of the material of words, so that we don’t know any more whether what we hear is poetry or music. At the end, words and poetry take over once again.

V: The different stages of preparing Thema were described by you in a long article. It was a highly complex, multifaceted job. Obviously, your experience with electronic music helped you a lot.

B: Of course. First of all, I defined the key points of the text. In vocal music, a great deal has to be sacrificed, destroyed because we cannot control everything. This was obvious also in the preparatory phase of Thema. After selecting the material, I linked the words according to their acoustical properties rather than simply their order of occurrence. After that, I connected them according to their meaning. In other words, I established an acoustical and a semantic frame and then transformed the words alternately according to the requirements of one or the other, with various technical means, most of them perhaps rudimentary: complicated editing, filters, acceleration, slowing down etc.

Excerpt from Oxford Studies of Composers: Berio

By David Osmond-Smith

Oxford Studies of Composers: Berio

Oxford University Press, 1991

The distinctive vocal style that Berio created in the sixties has received more critical attention, and attracted more imitators than any other part of his work. Its durable impact owes a good deal to an all-embracing delight in the voice and its resources. But here as elsewhere in Berio’s work, that apparently spontaneous exuberance exists in tension with a wider and more systematic perspective. Berio delves into texts to find in them elements, whether phonetic or semantic, that may be used as structural components in their own right. However remarkable his flair for the telling individual gesture, it is this sense of structural perspective that gives his vocal works their richness and resilience.

However, the seminal works of the early sixties were written not for ‘the voice’, but for a voice: that of Cathy Berberian. Berberian’s vocal career had gone somewhat into abeyance in the mid-fifties: the first performance of Chamber Music in 1953 was the last that she gave before the birth of her daughter, Christina. Apart from some minor recordings for radio, she devoted the next few years to looking after her child. But she was determined to return to singing, and in 1958 relaunched her career in Naples during the second series of Incontri Musicali concerts, where she performed Stravinsky and Ravel.

But while Berberian was developing her distinctive style of vocal theatre Berio was consolidating an approach to the voice within which individual gestures could contribute something more than anecdotal detail. His work at the RAI had brought him into contact with a number of talented young writers: among them, Umberto Eco, with whom he developed a close friendship. By 1957, they were pursuing shared enthusiasms: Eco introduced Berio to the complexities of Joyce’s Ulysses, and Berio set Eco on the track of de Saussure’s linguistics. One product of this cross-fertilization was a radio programme that they planned together entitled Onomatopea nel linguaggio poetico (onomatopoeia in poetic language). This at first was intended to cover a range of writers including Poe, Dylan Thomas and Auden. Although the final version of the programme included extracts from all of these read by Berberian, the project was quickly fined down to an intensive study of one specific passage from Ulysses: the ‘overture’ from the ‘Sirens’ chapter. Berio by now could see his way towards deriving a purely musical structure from this text. He recorded Berberian’s marvellously apt reading of it; he also recorded French and Italian translations of the same section using mixed voices. By creating counterpoints out of these, first within each language, then electronically transforming this mixture, he hoped to lead the listener step by step over the border between sense and sound: but the result proved too challenging, and was never broadcast. He therefore set about making an autonomous, and more focused tape piece, Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), which was based entirely on Berberian’s reading of Joyce’s original text.

Berio’s involvement with this particular passage from Ulysses was to have consequences far beyond Thema itself. One of the many factors governing the macrostructure of Ulysses is the association of each chapter with one of the arts: that of the Sirens’ chapter is music. This not only gave Joyce the opportunity to raise the alliterative and onomatopoeic qualities of his prose to their highest pitch, and to weave a prodigious number of song quotations into the narrative, it also encouraged him in the somewhat fanciful conceit of viewing the various entrances and exits that enliven the Ormond Bar at lunchtime as a fuga per canonem. His ‘overture’ to the chapter takes up a technique first hinted at in the ‘Wandering Rocks’ chapter, where an isolated and apparently alien phrase will appear in the midst of the narrative, only to reveal its significance when the reader passes on to another section, and there finds it in its own context (a device used by Joyce to suggest the simultaneity of two events in different parts of Dublin). The ‘overture’ to the ‘Sirens’ chapter frees this process from any narrative function. It consists entirely of dislocated phrases from the ensuing narration. These tell no story, so there is nothing to distract the reader from texture and rhythm—save that the mind, confronted with isolated images, begins to build hypothetical bridges between them, generating new meanings quite unrelated to those that each fragment is to adopt in the ensuing narrative.

Joyce’s example was to be put to abundant use in Berio’s future work. But in Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (thema, or ‘theme’ because he viewed the ‘overture’ as setting out the themes of the ensuing fuga per canonem), the focus was instead upon extending the process initiated by Joyce to its logical conclusion. Joyce had extracted from his musicalized narrative a mosaic that developed its own semantic and musical potentials. Berio now extracted from that mosaic purely musical elements, and used them to explore the borderline where sound as the bearer of linguistic sense dissolves into sound as the bearer of musical meaning: a territory that over the next decade he was to make very much his own. In part he did this by taking Joyce’s polyphonic imagery literally, and superposing texts upon themselves with slightly different rhythmic spacings: in effect, translating text into texture. But the operation that provided the key to much of his future vocal work was an analysis of Berberian’s recording that grouped words from the text in terms of their phonetic content.

Phonetic material can be analysed in two ways: either in terms of its acoustic structure, or in terms of the positions that the mouth and throat must take up in order to form it. (The two do not necessarily map on to each other in any straightforward way.) In view of his intensive work in the Studio di Fonologia at this time, it might have seemed natural to adopt the former approach. Indeed, had he chosen to combine vocal and electronic materials, as had Stockhausen in Gesang der Jünglinge two years before, such an approach would have been necessary. But unlike Stockhausen, Berio had opted to work entirely with his vocal recordings, and so he chose to sort out his materials in strictly articulatory terms. He grouped isolated words from Joyce’s text according to their vowel content, and arranged these groups as a ‘series’ determined by the position in the mouth used to articulate each vowel. But if the constraints of ‘natural’ articulation provided him with a way of ordering his material, he then proceeded to work in tension with it, juxtaposing and superposing phonetic elements so as to produce consonant groupings that the human voice would normally find hard to articulate in rapid succession (such as voiced and unvoiced plosives).

Out of this ‘impossible’ vocalism, comprehensible speech (usually a single word) momentarily emerges, only to be engulfed: relative comprehensibility has become a compositional parameter to be handled in much the same way as textural density or, within a pitched context, harmonic density. In one form or another, and with the sole exception of the more lyrical settings in Epifanie, this has remained a constant of Berio’s vocal style. It may be achieved by the fragmentation of originally linear texts, as Joyce did in assembling his ‘overture’, by superposition of texts, as Berio did in the initial stages of work on Thema, by dissolution of texts into their component phonetic materials, or more usually by a combination of these.

By focusing upon the phonetic borderline that divides sense from sound, and upon relative comprehensibility as a structural component, Thema set the agenda for Berio’s handling of language within music over a long period to come. It also focused the attention of his closest associates upon similar concerns: Pousseur’s electronic ballet Electre (1960) derived its materials exclusively from the speaking voice, and Maderna’s Dimensioni II of the same year sought to explore the potential of purely phonetic materials derived from a variety of languages, and combined as a phonetic ‘text’ by Hans G. Helms. In one respect. Dimensioni II provides a conceptual stepping-stone between Thema, and Berio’s next electronic/vocal project, Visage (1960-61). Helms’s test had to be turned into recorded sound, and Maderna therefore asked Cathy Berberian to read it, infusing it with whatever intonations her imagination might suggest. In Visage Berio went one step further. He dispensed with texts altogether, and allowed Berberian’s fertile imagination its head. In the recording studio, she improvised a series of monologues, each based on a repertoire of vocal gesture and phonetic material suggested by a given linguistic model, but in fact using no words from that language. Yet like any foreign conversation overheard in a train or a café, they were far from meaningless, and graphically conveyed ‘content’ by gesture and intonation. (One exhausting session was devoted entirely to different toes of laughter, an obsession to which Berio was to return in Sequenza III). Only one real word was included: ‘parole’, the Italian for ‘words’, which is precisely what everything around it was not. Out of these materials Berio built a montage so rich in suggestions and psychological drama that the RAI, for whom the work was originally intended, banned the work from the air-waves as ‘obscene’.

Excerpt from “Music After Joyce: The Post-Serial Avant-Garde,” By Timothy S. Murphy

By Timothy S. Murphy

“Music After Joyce: The Post-Serial Avant-Garde”

Hypermedia Joyce Studies, Volume 2, Number 1. Summer 1999.

Luciano Berio’s encounter with Joyce had less traumatic but no less profound effects than Boulez’s encounter did, though it came around the same period. Like Boulez, Berio was also born in 1925, in the Italian city of Oneglia. Berio’s first attempt to come to terms with Joyce came in 1953, when he set three poems from Chamber Music to music patterned after the melodic serialism of his teacher Luigi Dallapiccola (Berio, Two Interviews 53); although these songs show early signs of Berio’s uniquely lyrical approach to modern compositional innovations, they cannot be considered mature works either in their melodic structure or in their approach to the music/text relation. His second Joycean experiment, however, is much more significant, both for Berio’s own work and for the course of modern music. Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958) is, along with Varèse’s Poème électronique (1957-58) and Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge (1956), one of the classic works of electronic or “electro-acoustic” music, music composed directly on tape using pre-recorded and manipulated natural and electronic sounds. Constructed in collaboration with Umberto Eco, who had introduced Berio to Ulysses, Thema takes its point of departure from the opening “overture” of the “Sirens” chapter of Ulysses (U 11.1-36). Berio cites Joyce’s own claim that the formal structure of “Sirens” transposes the fuga per canonem (Berio, “Poésie” 27, Ellmann 462), though he notes that “the Joycean polyphony, naturally, refers only to the network of facts and characters: a reading voice is always a ‘solo’ voice and not a fugue” in itself (Berio, “Poésie” 27). Berio’s tape piece, on the other hand, is a literal fugue that “render[s] real the polyphony attempted on the page” by superimposing or overdubbing the voice of his then-wife Cathy Berberian onto itself three times (Berio, “Poésie” 28-29).

Thema uses only these voices and no electronic sounds, because Berio’s intention was “to produce a reading of Joyce’s text within certain restrictions dictated by the text itself,” and more broadly to establish a new relationship between speech and music, in which a continuous metamorphosis of one into the other can be developed. Thus, through a reorganization and transformation of the phonetic and semantic elements of Joyce’s text, “Mr. Bloom’s day in Dublin…briefly takes another direction, where it is no longer possible to distinguish between word and sound, between sound and noise, between poetry and music, but where we once more become aware of the relative nature of these distinctions and of the expressive character inherent in their changing functions” (Berio, liner notes).

Berio goes on to describe the formal restrictions and transformational rules used to create this piece as follows:

Once accepted as a sound-system, the text can gradually be detached from its frame of vocal delivery and evaluated in terms of electro-acoustic transformational possibilities. The text is thus broken down into sound families, groups of words or syllables organized in a scale of vocal colors (from ‘a’ to ‘u’) and a scale of consonants (from voiced to unvoiced), the ordering of which is determined by noise content. The extreme points of the latter scale, for instance, are constituted by the ‘bl’ grouping (from “Blew. Blue bloom…” [U 11.6]) and by ‘s’ (from the last line of this exposition…: “Pearls: when she. Liszt’s rhapsodies. Hissss” [U 11.36]). The members of these sound families are placed in environments other than their original textual contexts, the varying length of the portions of context establishing a pattern of degree of intelligibility of the text (Berio, liner notes).

Each element of the text thus broken down is systematically transformed according to three processes whose application is determined by the original nature of the element itself. Elements marked by abrupt breaks or sonic discontinuity (such as “Goodgod henev erheard inall” [U 11.29]) are converted into periodic or pulsed ones, and then stitched together into continuous lines of sound. Elements that are initially continuous, like sibilants (for example “Hissss” [U 11.36]), become periodic and ultimately discontinuous through electronic manipulation and transformation. Finally, periodic or rhythmically repetitive sound elements (like “thnthnthn” [U 11.2]) are rendered first continuous and then discontinuous. All these transformations are carried out by tape editing, superimposition of identical elements with varying time relations (also called “phase shifting” and associated later with the work of Steve Reich), wide frequency and time transpositions, and filtering (Berio, “Poésie” 31-32, liner notes). The original text is often not easily recognizable because of these extensive but very precise transformations.

In Thema, Berio claims, “we pass from a ‘poetic’ listening space to a ‘musical’ listening space. This musical listening space is based on the poetic material, on an object which is transformed and becomes music” (Berio, “Entretien” 63).

Text

Thema (Omaggio a Joyce)

Text by James Joyce

From the “Sirens” Episode of Ulysses

BRONZE BY GOLD HEARD THE HOOFIRONS, STEELYRINING IMPERthnthn thnthnthn.

Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips. Horrid! And gold flushed more.

A husky fifenote blew.

Blew. Blue bloom is on the

Gold pinnacled hair.

A jumping rose on satiny breasts of satin, rose of Castille.

Trilling, trilling: Idolores.

Peep! Who’s in the . . . peepofgold?

Tink cried to bronze in pity.

And a call, pure, long and throbbing. Longindying call.

Decoy. Soft word. But look! The bright stars fade. O rose! Notes chirruping answer. Castille. The morn is breaking.

Jingle jingle jaunted jingling.

Coin rang. Clock clacked.

Avowal. Sonnez. I could. Rebound of garter. Not leave thee. Smack. La cloche! Thigh smack. Avowal. Warm. Sweetheart, goodbye!

Jingle. Bloo.

Boomed crashing chords. When love absorbs. War! War! The tympanum.

A sail! A veil awave upon the waves.

Lost. Throstle fluted. All is lost now.

Horn. Hawhorn.

When first he saw. Alas!

Full tup. Full throb.

Warbling. Ah, lure! Alluring.

Martha! Come!

Clapclop. Clipclap. Clappyclap.

Goodgod henev erheard inall.

Deaf bald Pat brought pad knife took up.

A moonlight nightcall: far: far.

I feel so sad. P. S. So lonely blooming.

Listen!

The spiked and winding cold seahorn. Have you the? Each and for other plash and silent roar.

Pearls: when she. Liszt’s rhapsodies. Hissss.

Recordings

Thema was recorded at the Studio di Fonologia Musicale di Milano in 1958. Since then it has appeared on dozens of LPs, cassettes, and compact discs. It may also be found on various early electronic music anthologies. Many of these CDs have been deleted, and some are quite expensive to purchase used. Fortunately, you can always listen to Thema on YouTube, or here at the Brazen Head. After all, being a tape piece, every CD features the same recording.

|

|

Berio: Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958)

CD: Acousmatrix 7: Berio/Maderna. BVHaast 9109 (1992)

CD Reissue: Acousmatrix—History of Electronic Music VII: Berio — Maderna. BVHaast 9109 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube | Brazen Head

This compilation of Berio and Maderna’s electronic works was released as part of the Acousmatrix series, and is currently the most accessible release of Thema. Unfortunately the CD has been deleted, but you can still purchase it on MP3 or CD-quality FLAC.

Berio: Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958)

CD: Luciano Berio: Many More Voices. BMG Classics/RCA Victor 09026-68302-2 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube | Brazen Head

Another compilation of Berio’s electronic works, this CD has unfortunately been deleted.

Online Video

The following live performances are available on YouTube.

Signal

Dancer: Xiao-Xuan Yang

Recorded 19 November 2019 at the Black Box Theater at the New College of Florida, Signal is a solo dance performed to Berio’s Thema.

Additional Information

Poésie et musique: une expérience

A French translation of Berio’s 1959 essay, “Poesia e musica—un’esperienza,” from Incontri Musicali No. 3. Berio’s own explanation is by far the most informative piece on Thema, and can be read in English by running it through Google translate: “Music and Poetry—an Experience.” This AI translation is surprisingly good, rendering this important essay entirely intelligible to English audiences.

JSTOR Paywall:

Poésie et musique: une expérience

Luciano Berio, Revue belge de Musicologie, Vol. 13, No. 1/4, 1959, Musique expérimentale/Experimentele Muziek, pp. 68-75. The same French translation of Berio’s essay as above, just on JSTOR.

The Introduction to “Sirens” and the Fuga per Canonem

Heath Lees, James Joyce Quarterly, Fall, 1984, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 39-54.

The Mystery of the Fuga per Canonem Solved

Susan Sutliff Brown, European Joyce Studies, 2013, Vol. 22, JOYCEAN UNIONS: Post-Millennial Essays from East to West, pp. 173-193.

Luciano Berio: Other Joyce-Related Works

Luciano Berio Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Luciano Berio profile.

Chamber Music (1953)

Three songs adapted from Joyce’s poetry.

Epifanie (1961/65)

A variable sequence of orchestral and vocal pieces, including texts from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.

Traces (1964)

Only given one performance and withdrawn, this “ghost opera” about racism was partially inspired by the “Circe” episode of Ulysses.

Sinfonia (1968/69)

This tour de force of music, voice, and sound incorporates text from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable. While it has no overt Joycean references, Sinfonia is frequently compared to Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

A-Ronne (1974/75)

A “documentary” on a poem by Edoardo Sanguineti, this piece of vocal virtuosity contains a reference to Finnegans Wake.

Outis (1996)

Berio’s opera about the transformations of Odysseus includes material borrowed from Joyce’s Ulysses.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 17 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com