Joyce Music – Berio: Sinfonia (Notes)

- At November 03, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Sinfonia: Liner Notes, Essays and Interviews

With eight commercial recordings of Sinfonia to choose from, it would be overkill to reprint every set of liner notes! The truth is, many of them say much the same thing, mostly rephrasing Berio’s original notes from the 1968 Columbia LP. I’ve included those original notes, along with Berio’s notes on the completed, 5-movement Sinfonia, even though there’s some repetition. I have also included liner notes written by Roger Marsh. A composer best known for his own Joycean composition Not a Soul But Ourselves, Marsh was the producer for all of Naxos’ James Joyce recordings, so knows a thing or two about Joyce himself! Marsh actually wrote two sets of liner notes. His first was for the 1990 Decca recording with Riccardo Chailly. In 1996 he expanded these notes for the Philips recording with Sermon Bychkov. I have included the “expanded” version of the latter recording, adding only a paragraph about Joyce borrowed from the Decca set. These are followed by excerpts from Berio’s Two Interviews, and an essay on Sinfonia written by Joycean scholar Murat Eyüboglu.

[Back to Sinfonia Main Page]

Liner Notes from 1969 Columbia LP

By Luciano Berio

Berio: Sinfonia; Nones; Allelujah II

Columbia, 1969

The four sections into which Sinfonia (composed in 1968) is divided are not to be taken as movements analogous to those of the classical symphony. The title, in fact, must be understood only in its etymological sense of “sounding together” (in this case, the sounding together of instruments and eight voices). Although their expressive characters are extremely diversified, these four sections are generally unified by similar harmonic and articulatory characteristics (duplication and extended repetition being among the most important).

I. The text of the first part consists of a series of short fragments from Le cru et le cuit by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. These fragments are taken from a section of the book that analyzes the structure and symbology of Brazilian myths about the origins of water and related myths characterized by similar structure.

II. The second section of Sinfonia is a tribute to the memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Here the vocal part is based on his name, nothing else.

III. The main text for the third section includes excerpts from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, which in turn prompt a selection from many other sources, including Joyce, spoken phrases of Harvard undergraduates, slogans written by the students on the walls of the Sorbonne during the May 1968 insurrection in Paris (which I witnessed), recorded dialogues with my friends and family, snatches of solfège, and so on.

IV. The text for the fourth section, a sort of coda, is based on a short selection from those used in the three preceding parts. The treatments of the vocal part in the first, second and fourth sections of Sinfonia resemble each other in that the text is not immediately perceivable as such. The words and their components undergo a musical analysis that is integral to the total musical structure of voice and instrument together. It is precisely because the varying degree of perceptibility of the text at different moments is a part of the musical structure that the words and phrases used are not printed here. The experience of “not quite hearing,” then, is to be conceived as essential to the nature of the work itself.

Section III of Sinfonia, I feel, requires a more detailed comment than the others, because it is perhaps the most “experimental” music I have ever written. It is another homage, this time to Gustav Mahler, whose work seems to bear the weight of the entire history of music; and to Leonard Bernstein for his unforgettable performance of the “Resurrection” Symphony during the 1967-68 season. The result is a kind of “voyage to Cythera” made on board the third movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony. The Mahler movement is treated like a container within whose framework a large number of references are proliferated, interrelated and integrated into the flowing structure of the original work itself. The references range from Bach, Schoenberg, Debussy, Ravel, Strauss, Berlioz, Brahms, Berg, Hindemith, Beethoven, Wagner and Stravinsky to Boulez, Stockhausen, Globokar, Pousseur, Ives, myself and beyond. I would almost say that this section of Sinfonia is not so much composed as it is assembled to make possible the mutual transformation of the component parts. It was my intention here neither to destroy Mahler (who is indestructible) nor to play out a private complex about “post-Romantic music” (I have none) nor yet to spin some enormous musical anecdote (familiar among young pianists). Quotations and references were chosen not only for their real but also for their potential relation to Mahler. The juxtaposition of contrasting elements, in fact, is part of the whole point of this section of Sinfonia, which can also be considered, if you will, a documentary on an objet trouvé recorded in the mind of the listener. As a structural point of reference, Mahler is to the totality of the music of this section what Beckett is to the text. One might describe the relationship between words and music as a kind of interpretation, almost a Traumdeutung, of that stream-of-consciousness-like flowing that is the most immediate expressive character of Mahler’s movement. If I were to describe the presence of Mahler’s “scherzo” in Sinfonia, the image that comes most spontaneously to mind is that of a river, going through a constantly changing landscape, sometimes going underground and emerging in another, altogether different, place, sometimes very evident in its journey, sometimes disappearing completely, present either as a fully recognizable form or as small details lost in the surrounding host of musical presences.

Liner Notes from 1986 Erato LP

By Luciano Berio

Berio: Sinfonia; Eindrücke

Erato, 1986

The title is not meant to suggest any analogy with the classical symphonic form. It is intended purely etymologically: the simultaneous sound of various parts, here eight voices and instruments. Or it may be taken in a more general sense as the interplay of a variety of things, situations and meanings. Indeed, the musical development of Sinfonia is constantly and strongly conditioned by the search for balance, even identity between voices and instruments; between the spoken or the sung word and the sound structure as a whole. This is why the perception and intelligibility of the text are never taken as read, but on the contrary are integrally related to the composition. Thus, the various degrees of intelligibility of the text, along with the hearer’s experience of almost failing to understand, must be seen as essential to the very nature of the musical process.

The text of the first part is made up of a series of extremely short extracts from Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Le cru et le cuit, and one or two other sources. In these passages, Lévi-Strauss analyses the structure and symbolism of Brazilian myths of the origin of water, or other similarly structured myths.

The second part of Sinfonia is a tribute to the memory of Martin Luther King. The eight voices simply send back and forth to each other the sounds that make up the Black martyr, until they at last state his name clearly and intelligibly. The main text of the third part is made up of fragments from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable, which in turn generate a large number of references and quotations from day-to-day life.

The text of the fourth part mimes rather than enunciates verbal fragments drawn from the preceding parts (with, at the beginning, a brief reference of Mahler’s Second Symphony).

Finally, the text of the fifth part takes up, develops and compliments the texts of the earlier parts, and above all gives these fragments narrative substance (being drawn from Le cru et le cuit), whereas in the first part they were presented merely as poetic images.

The third part of Sinfonia calls for more detailed comment, since it is perhaps the most experimental work I have ever written. The piece is a tribute to Gustav Mahler (whose work seems to carry all the weight of the last two centuries of musical history) and, in particular, to the third movement of his Second Symphony (“Resurrection”). Mahler bears the same relation to the whole of the music of this part as Beckett does to the text. The result is a kind of “voyage to Cythera” that reaches its climax just before the third movement (the scherzo) of the Second Symphony. This movement is treated as a generative source, from which are derived a great number of musical figures ranging from Bach to Schönberg, Brahms to Stravinsky, Berg to Webern, Boulez, Pousseur, myself and others. The various musical characters, constantly integrated in the flow of Mahler’s discourse, are combined together and transformed as they go.

In this way these familiar objects and faces, set in a new perspective, context and light, unexpectedly take on a new meaning. The combination and unification of musical characters that are foreign to each other is probably the main driving force behind this third part of Sinfonia, a meditation on a Mahlerian “objet trouvé.” If I were asked to explain the presence of Mahler’s scherzo in Sinfonia, the image that would naturally spring to mind would be that of a river running through a constantly changing landscape, disappearing from time to time underground, only to emerge later totally transformed. Its course is at times perfectly apparent, at others hard to perceive, sometimes it takes on a totally recognisable form, at others it is made up of a multitude of tiny details lost in the surrounding forest of musical presences.

The first four parts of Sinfonia are obviously very different one from the other. The task of the fifth and last part is to delete these differences and bring to light and develop the latent unity of the preceding four parts. In fact the development that began in the first part reaches its conclusion here, and it is here that all the other parts of the work flow together, either as fragments (third and fourth parts) or as a whole (the second).

This the fifth part may be considered to be the veritable analysis of Sinfonia, but carried out through the language and medium of the composition itself.

Sinfonia, composed for the 125th anniversary of the New York Philharmonic is dedicated to Leonard Bernstein.

Liner Notes from 1996 Philips LP

By Roger Marsh

Berio: Canticum Novissimi Testamenti II; Sinfonia

Philips, 1996

As Luciano Berio approaches the beginning of his eighth decade, it becomes increasingly clear that no composer since Stravinsky has had a greater ability to delight, astonish, excite and move audiences than this extraordinarily gifted musician. Like Stravinsky, Berio has always had the ability to keep both critics and public guessing about what musical challenges may be in store. For there has never been a school, system or academic orthodoxy to which he has adhered, but rather—like Stravinsky—an insatiable appetite for exploration allied to a distinctive musical voice and a genuine desire to communicate. Because of this Berio too has had detractors, on the one hand those suspicious of a composer whose music can become so popular, and on the other those for whom his work is still too difficult. Berio would doubtless hold out more hope for the second category, whose numbers in any case are rapidly dwindling.

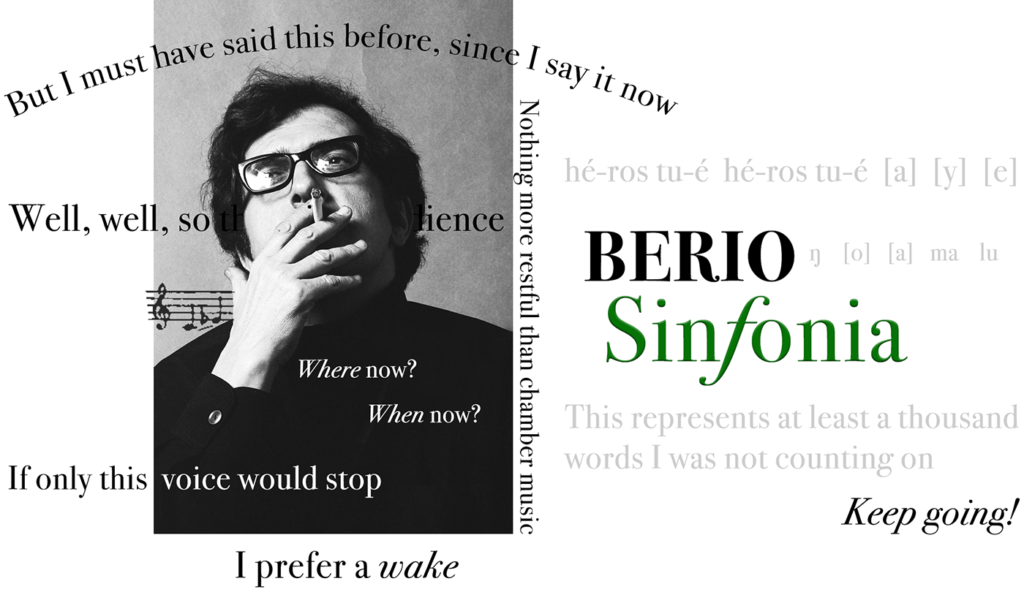

Sinfonia (1968), by now generally regarded as a twentieth-century classic, stands as a monument to the explosive years of the 1960s and is without doubt Berio’s most popular and well-known work. Scored for large orchestra fronted by eight amplified voices, it is not in the classical sense a “symphony.” Rather Berio intends the title to be understood in its literal sense of “sounding together,” although it is worth noting that there are precedents for symphonies with voices, and that the five-movement structure of Sinfonia is also no novelty. Indeed the arrangement of the movements—second movement slow, third movement a scherzo—and the importance to the piece of Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony make this a clear comment on the symphonic tradition, even if not actually a part of it. All the same, “sounding together” is a far more useful way of understanding what the piece is all about, for Sinfonia brings together an immense catalogue of potentially diverse elements, and unifies them in a way which is nothing short of miraculous. Dedicated to Leonard Bernstein, the work was composed for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and for the hugely successful Swingle Singers, whose vocal interpretations of Bach were, for a few years, as popular as the music of the Beatles. Their intimate singing style and familiarity with close microphone technique permitted Berio to exploit the full range of vocal possibilities, from full voice to whispering, and in a way this is the key to understanding Sinfonia. For although there is an elaborate and complex text, especially in the first and third movements, the way in which it is delivered often obscures meaning in favour of “instrumental” effect. Berio himself has remarked that “the experience of ‘not quite hearing’ is to be conceived as essential to the nature of the work. “To put it another way, the text is not more important than the resulting musical experience. The following is a brief guide to the five movements of Sinfonia:

(1) The text of this movement consists of fragments from Le cru et le cuit (The Raw and the Cooked) by the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in which some 200 Brazilian myths are compared for their remarkable similarities. The myths concern the origins of fire (feu) and water (eau céleste = rain, eau terrestre = rivers), explained by long tales concerning the trials, penances and ultimate death of a “hero” (héros tué). As Berio’s singers attempt to relate and to reconcile these tales, the orchestra is provoked into activity which develops from and ultimately swamps them. At the end of the movement, beneath densely moving clusters of orchestral sound, a solo piano appears to emerge. This solo is brought to a halt by the return of the sustained chord which opened the work, but it will be taken up again in the last movement.

(2) This is a meditation on the name of Martin Luther King, the assassinated civil rights leader (a contemporary héros tué). Beginning on equal terms with the orchestra, the voices use only the fragmented syllables of his name, gradually piecing them together towards a full statement at the climax of the movement.

(3) The scherzo from Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony supports a wealth of quotations from the music of Ravel, Debussy, Schoenberg, Beethoven, Stravinsky and many others, while quotations from Joyce and Valéry join solfège, student slogans from the Paris riots of 1968, and indications from some of the musical scores quoted. The principal text is from Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable, whose disembodied narrator maintains a continuous unpunctuated monologue which represents the only proof of his continued existence (“Keep going on; call that going? call that on?”). The plight of Beckett’s character, helplessly observing the procession of images parading about him, recalls Mahler’s own comments on his scherzo: “If, at a distance, you watch a dance through a window, without being able to hear the music, then the turning and twisting movement of the couples seems senseless, because you are not catching the rhythm that is the key to it all. You must imagine that, to one who has lost his identity and his happiness, the world looks like this—as if reflected in a concave mirror.”

(4) Following the final low C of Mahler’s scherzo, the voices take up with the same notes which begin Mahler’s fourth movement. The words of Mahler’s soprano (“O Röschen rot”) are transformed into “Rose de sang” (Rose of blood), closely recalling Lévi-Strauss’s “eau de sang” from the first movement. As the music drifts upwards, the whisperings and meditative intonations of the voices suggest a prayer for the various dead heroes of the previous movements.

(5) The piano launches immediately into a solo which appears to be a continuation of that first heard in the opening movement, but is quickly challenged by the entry of soprano and flute, as though estranged from the piano, also recalling ideas from the earlier movement. As the remaining voices and orchestra enter it becomes clear that we are to be assailed by ghosts from all the previous movements, their spectral nature combining to form images which are at the same time new and familiar. Most of the text derives from Lévi-Strauss, but if semantic logic was hard to come by in the first movement, it is even more elusive here. By now the synthesis is so complete that the musical discourse has an inevitability of its own. It is no surprise to be brought back by a process of gradual transformation to the same flute, the same piano chord and the same tam-tam stroke which ended the first movement.

In Roger Marsh’s liner notes for the 1990 Decca recording, he included this Joycean thought:

Such a web of inter-relationships is not easily untangled, nor is it expected by the composer that an audience should be able consciously to observe these connections. Rather, as Berio has explained, ‘the experience of “not quite hearing is to be conceived as essential to the nature of the work’. Thus the concept is Joycean, not in scale (Finnegans Wake took seventeen years to write and cannot be read in an evening) but in design. As in Finnegans Wake all history is here, processed in a way which sees more virtue in the confusion of past and present than in their separation. When musical ideas from the second movement return in the fifth, combined with texts from the first and quotations from the third, the effect is not disorientating but exhilarating. If, as Berio has said, the fifth movement completes the business begun in the first, it also suggests that the process of re-examination and re-composition might, in theory, go on indefinitely, or at the very least that, as with Finnegans Wake, the end is no more than a return to the point of departure.

Excerpt from Luciano Berio: Two Interviews

By Luciano Berio & Rossana Dalmonte

Two Interviews

Marion Boyars, 1985

Dalmonte: To go back to the principle of transformation that you were talking about before. How do you connect your use of folklore, whether as gesture or as process, with the function that quotation and self-quotation have in your work? I’m thinking of a work like Sinfonia, for instance.

Berio: There’s a very close link, provided that you don’t view the third part of Sinfonia, to which you’re no doubt referring, as a collage of quotes. I’m not interested in collages, and they amuse me only when I’m doing them with my children: then they become an exercise in relativizing and “decontextualizing” images, an elementary exercise whose healthy cynicism won’t do anyone any harm. This third part of Sinfonia has a skeleton which is the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony—a skeleton that often re-emerges fully fleshed out, then disappears, then comes back again… But it’s never alone: it’s accompanied throughout by the “history of music” that it itself recalls for me, with all its many levels and references—or at least those bits of history that I was able to keep a grip on, granted that often there’s anything up to four different references going on at the same time. So the scherzo of Mahler’s Second Symphony becomes a generator of harmonic functions and of musical references that are pertinent to them which appear, disappear, pursue their own courses, return to Mahler, cross paths, transform themselves into Mahler or hide behind it. The references to Bach, Brahms, Boulez, Berlioz, Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Strauss, Stockhausen etc. are therefore also signals which indicate which harmonic country we are going through, like bookmarkers, or little flags in different colours stuck into a map to indicate salient points during an expedition full of surprises.

I’d had it in mind for a long time to explore from the inside a piece of music from the past: a creative exploration that was at the same time an analysis, a commentary and an extension of the original. This follows from my principle that, for a composer, the best way to analyze and comment on a piece is to do something, using materials from that piece. The most profitable commentary on a symphony or an opera has always been another symphony or another opera. My Chemins are the best analyses of my Sequenzas, just as the third part of my Sinfonia is the most developed commentary that I could have possibly produced on a piece by Mahler. But originally, the idea of this third part of Sinfonia was linked not to Mahler, but to Beethoven. I was in fact thinking of harmonically “exploding” the last three movements of Beethoven’s Quartet in C sharp minor, Op. 13l—though without quotations, and with “little flags” composed by me instead. The vocal parts would have had a more instrumental character and the text would naturally have been quite different. I finally opted for Mahler not only because his music proliferates spontaneously, but also because it allowed me to extend, transform and comment on all of its aspects: including that of orchestration. I needed, that is, a structural basis that could be recognized every so often in its original form. Translating Beethoven’s Op. 131 into orchestral terms would have been a very risky operation and, in view of the task in hand, not an entirely justified one. And using Mahler was also a tribute to Leonard Bernstein who has done so much for his music. As you know, Sinfonia is dedicated to him.

However, this voyage to Cithera on board a Mahlerian vessel only acquires a complete sense when it is itself the subject of commentary in the fifth and final part of Sinfonia, which is by far the most complex because it takes up, transforms and comments on all the others. The first four parts of Sinfonia are to the fifth as Mahler’s scherzo is to the third. Thus the skeleton, the carrying structure of the fifth part, is made up of the four preceding parts, though they often appear in summary fashion—sometimes almost like shorthand, but at other times complete. But the order in which the fragments appear is changed. For example, the second part appears complete, transcribed from one end to the other, alongside salient elements from the third part and some from the first—and also some new elements that have been forming in the meantime. Thus the second part becomes the carrying structure for many other previously heard elements which appear as contracted fragments, assimilated instrumentally and vocally with new elements that comment on the commentary… The unforeseen and discontinuous dislocation of previously heard events provokes a sort of block in the (musical) stream of consciousness that characterized the previous parts, and particularly the third. The memory is continually stimulated and put to work, only to be contradicted and frustrated. It’s finally onto an element from the first part that the whole development converges, thus becoming more homogeneous and unanimous. The first part never came to a proper ending, it suddenly stopped and remained open. The fifth part concludes Sinfonia by bringing to an end the suspended development of the first. Thus the third part of Sinfonia is both the centre and the macroscopic model of the entire work. It also has a centrifugal function in as much as its mechanisms involve the totality of the work, projecting and amassing fragments of that totality in the fifth part.

As you can see, we’re a long way away from a collage of quotations. Sinfonia is a very homogeneous work that looks within itself. The text is treated in a way that is analogous to the musical development, and is very complex. David Osmond-Smith has finished a long and exhaustive study of Sinfonia that pays particular attention to the way the texts are used. Simplifying as much as possible, what happens is that the first part of Sinfonia elaborates fragments from a text by Claude Lévi-Strauss (Le cru et le cuit), as if they were starting points for a narration that is continually interrupted. It’s Lévi-Strauss as a great writer that we’re dealing with here and not, in any explicit way, Lévi-Strauss as a great anthropologist. As I was saying earlier, this first part also has an interrupted musical development—just as it looks as though it’s turning into a concerto for piano and orchestra; it’s a development which will be taken up again and seen through to an end in the fifth and last part. The second part has a totally different musical structure, and it has no text as such, only an alternation of phonetic elements that lead to the gradual “disclosure” and enunciation of the name of the black martyr Martin Luther King. Or rather “O Martin Luther King” to give greater continuity and completeness to the sequence of vowels. The third part has a pilot text by Samuel Beckett (taken from The Unnamable), a proliferating text that provides a parallel to Mahler’s proliferating musical “text”. One of the most important proliferations of the Beckett text (though not the only one) is the sequence of verbal signs which describe, sometimes metaphorically, sometimes explicitly, the various stages of the harmonic voyage, musically marked and punctuated by the quotations. The fourth part remains fixated on the first two notes and the first two words of the fourth movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony—the latter translated into French so as to allow a fleeting link with an image of Lévi-Strauss’s “appel bruyant”. Thus “O Räschen roth (rose de sang appel bruyant)”. Finally, the fifth part parallels the music by taking up fragments from the texts of the four previous parts. The interrupted fragments of Lévi-Strauss as great writer that appeared in the first part are finally completed, the discourse is conducted to one of its possible conclusions, and as in the structure of the music, the use of the text suggests that it may have not only a poetic, but also a scientific basis. In fact, it’s only then that I try to pay homage to Lévi-Strauss as a great anthropologist.

A new recording of Sinfonia conducted by Pierre Boulez with the Orchestre Nationale de Paris is about to come out. The existing one is unfortunately incomplete because, as so often happens, it was recorded immediately after the first performance of the first four parts in New York in 1968. I managed to finish the fifth part only three months later, when I had thoroughly convinced myself of its necessity.

Excerpt from Essay: “Davies, Berio, and Ulysses”

By Murat Eyüboglu

Bronze by Gold: Joyce and Music

Garland Publishing, 1999

Evocation of a sense of history has largely to do with the referential nature of the artistic material. Identifying the references and allusions in Ulysses, as well as articulating the ways in which Joyce tropes and emplots his preexisting material, are interpretive acts crucial to understanding the historical content of Joyce’s work. In this respect, Davies’s Missa poses a problem in that it parodies preexisting styles, rather than preexisting works. Parody in the Missa, in other words, occurs through a detour into pastiche. This ironized pastiche, while defining a satirical stance toward the styles it represents, does not anchor us in a specific historical reality or a compositional history.

Luciano Brio’s Sinfonia does precisely that: it provides us with a “history of music” (Berio, Interviews, 107) worthy of Ulysses in the profuseness of its allusions. Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic during Berio’s years of residence on the East Coast of America, and written partially in Sicily, Sinfonia was also composed in 1968, against a political background of student uprisings and Martin Luther King’s assassination, and an artistic background where the extreme compositional practices of integral serialism and chance operations appeared to be the Scylla and Charybdis of music composition. In an interview with Rossana Dalmonte in 1981, Berio described the third movement as follows:

This third part of Sinfonia has a skeleton which is the scherzo from Mahler’s Second Symphony—a skeleton that often re-emerges fully fleshed out, then disappears, then comes back again… But it’s never alone: it’s accompanied throughout by the “history of music”

(Interviews, 107)

Much like the palimpsest effect that Joyce creates through his treatment of Homer’s Odyssey, Berio embeds a dizzying number of simultaneous and successive quotations from music history into Mahler’s Scherzo, and thus creates a disorienting and seemingly chaotic musical surface. As is characteristic of the parody technique, however, the semantic content emerges out of the various tensions between the host work and the target works. Berio borrows the topos of Mahler’s Scherzo as a “satire upon mankind” and greatly elaborates its theme: the Wunderhorn poem on which Mahler’s movement is based depicts, in a comically pictorial setting, Saint Anthony’s sermon to the fish. The fish listen to the sermon attentively like “rational creatures” but remain unaffected by the saint’s words: the closing stanza of the poem tells us that in the end “the pike remain thieves […] the crabs go backwards […] the carps gorge a lot […] the sermon had pleased” (Porter, 52), but it is forgotten. To this forgetting Berio responds by a large number of recollections. How do we come to terms with the parodic manipulations of the past and comment on the “sense of history” thus evoked in Berio’s work?

The first problem that should give us pause, in this respect, is in which terms, if at all, this vertiginous movement represents a “history of music.” I propose to approach this question through Hayden White’s meditations on the poetics of historiography in his Metahistory. White defines a historical work as “a verbal structure in the form of a narrative prose discourse that purports to be a model, or icon, of the past structures and processes in the interest of explaining what they were by representing them” (2; emphasis in the original). In drastically simplified terms, it is the central thesis of Metahistory that in their renditions of reality, history and fiction are both subject to the same models of emplotment, such as tragedy, comedy, and satire, and both exploit the rhetorical tropes that establish, at precritical levels, relationships of cause-and-effect, and agent-and-act. In other words, “the difference between ‘history’ and ‘fiction’ resides in the fact that the historian finds’ his stories whereas the fiction writer ‘invents’ his” (White, 6). For several reasons, the categories articulated by White may appear incongruous with the language of music criticism: fiction and nonfiction are not meaningful categories in music, and even if musical forms can be said to emplot conflicts and reconciliations, the essential difference between literal and figural language that allows the rhetorical devices of metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche to operate is an ambiguous one in music.

When a fragment of music appears as a quotation, however, recontextualized in a new environment, it is deprived of the immediacy with which we would have understood it in its original context. I do not mean to suggest here that musical experience is an immediate one, only shattered by parody and decontextualization. The difference between the mediacy and immediacy of various musical experiences is a difference of degree. While the rhetoric and the impact of a certain kind of repertoire might depend on an immediacy effect—in which case mediation is not absent but only transparent to the listener—parodic compositions self-consciously cultivate a mediation effect. It is through the distance between the mediacy and the immediacy of musical experience that the works and quotations that are parodied (depending, as we shall see, on how they are used) acquire a meta-musical quality, a quality that by virtue of its reflexiveness as well as its self-reflexiveness allows the composer a rhetorical space for topological and meta-topological maneuvers. It is not my intention to provide a thorough analysis of Sinfonia’s third movement, but to show the tropological means by which the work is able to make a comment on history and thus become a historical work.

If the “history of music” that accompanies Mahler’s Scherzo is a conspicuously incomplete one, it is not because the music library in Sicily to which Berio had access while writing Sinfonia had a poor collection. The refractory layout of the third movement is, in fact highly thematicized, its principal focus being a water theme derived from Mahler’s aquatic evocation of Saint Anthony’s sermon to the fish. Other water references are sprinkled throughout Berio’s score: Schoenberg’s Opus 16, including the Farben movement (with its subtitle “Summer Morning by a Lake”), Debussy’s La Mer, the drowning scene from Act III of Berg’s Wozzeck, and the second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 6, “Scene by the Brook” are all represented through quotations.

Let us now attempt a tropological reading of some of these quotations. The citation from Beethoven’s Symphony no. 6 is a six-note arching motif, quoted at its original pitch level and B-flat clarinet instrumentation (Berio, Sinfonia, X+3; Figure 7-1) The first operation is a synecdochic one in which the part stands for the whole; in other words, the short clarinet motif from the second movement of the symphony stands for the work in its entirely. The reason for citing the Pastoral Symphony is its celebration of nature (on a brook) and the reconciliation of nature and culture implicit therein: nature is neither a self-evident given nor a lost and irretrievable phenomenon; rather, it is one that can be enjoyed and represented in a symphony. In Berio’s score, this quotation is accompanied by the line “It is late now, he shall never hear again the lowing cattle, the rush of the stream” from Beckett’s Unnamable. This juxtaposition negates the ethos of the musical citation, inverts its implicit content as a celebration of nature by overlaying upon it a pessimistic statement of “no longer.”

Wozzeck citations in Sinfonia are handled quite differently. Quoting the music of Wozzeck’s drowning from Act III of the opera, Berio presents the water scene as a site of disenchantment, guilt, murder, and suicide. In the accompanying text the alto makes a trivializing remark regarding Wozzeck’s murder of Marie: “Just a small murder,” she says, while the basses take up the lines of the Captain and the Doctor (Berio, Sinfonia, S–T+4). In a metonymic relationship the topoi of Wozzeck and the third movement of Sinfonia appear in contiguity. Of the overall satirical Mahlerian plot of Saint Anthony’s fruitless preaching to the fish, the tragic pessimism of Wozzeck becomes an exemplum.

Another piece that is represented with a large number of quotes is Ravel’s La Valse. Much like Sinfonia, the rhetoric of La Valse depends on quotation, obliteration, and distortion. The waltz is not the substance but rather the topos of La Valse where the Viennese dance form stands at the same meta-musical remove to the host work, as do the quotations in Sinfonia. La Valse also shares the satirical-historical emplotment of Sinfonia in its depiction of—in Ravel’s words—“the glow of the chandeliers” at an “Imperial Court about 1855” (Larner, 174) through the perspective of Vienna’s dilapidated glamour in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. La Valse then is a historical anterior model to Sinfonia and in the language of rhetorical tropes, the two works stand in a metaphorical relationship to each other on account of the similarity they display.

Though this tropological analysis could be extended indefinitely, I don’t believe that all the quotations in the third movement of Sinfonia can be explained with the same degree of specificity. Berio’s close study of Joyce is nevertheless highly detectable in Sinfonia: both Ulysses and the third movement of Sinfonia rely on preexisting models that they “explode”—to use Berio’s term (Interviews, 107)—through an overabundance of historical references. In both works the dizzying surface gives rise to consistent patterns, which at the same time, shot through with parody, irony, and satire, defies reductionist attempts at explanation. History in Joyce and Berio appears as a phenomenon that can be referred to and grasped, but an emplotment that grants it a teleological form is denied. Davies’s Missa, on the other hand, presents a more synchronic view of history on account of its self-conscious avoidance of a historically specific referentiality. Both Davies and Berio, however, borrow the satirical ethos of Ulysses, cultivating a manner of excess that perpetually risks overwhelming its own historical commentary.

Another glimpse at the homologies evoked earlier between Joyce and his musical contemporaries on the one hand, and their successors in the late sixties on the other, might bring these relationships into sharper focus. To generalize, we can maintain that by the turn of the century and during the two decades that followed, the objectifying and coherent point of view of the bourgeois individual was replaced by the simultaneous presence of multiple perspectives in literature, painting, and music alike: the multipersonal representation of consciousness in the works of Joyce and Woolf, the attempts to dissolve the unifying gaze of the painter in Cézanne and the ensuing cubism, and the heterogeneity of musical material in Ives and Mahler are symptoms of a condition in which the subject’s consciousness is depicted as both fractured and composite. The return to the musical languages of decentered subjectivity in the late sixties when, as Boulez once put it, “‘contemporary music had finished its ascetic period and was turning increasingly towards the luxuriant” (296), suggestively coincided with the emergence of a plurality of new voices in the social realm, represented by decolonized populations, the rise of feminism, civil rights, and antiwar movements. It was in this historical moment that Joyce was reread by composers as a model of parodic palimpsest, and an open text that emplots an ironic teleology.

Editor: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Main Sinfonia Page: Sinfonia

Main Berio Page: Luciano Berio

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com