Joyce Music – Berio: Epifanie

- At November 27, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

This triviality made him think of collecting many such moments together in a book of epiphanies. By epiphany—a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether in the vulgarity of speech or gesture, or in a memorable phrase of the mind itself. He believed that it was for the man of letters to record these epiphanies with extreme care, seeing that the themselves are the most delicate and evanescent of moments.

—James Joyce, “Stephen Hero”

Epifanie/Epiphanies

(1959-61/65/91)

For female voice and orchestra

History

In the mid-1950s, composers began experimenting with the spatial arrangements between instrumental groups. Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gruppen is perhaps the most famous example, in which an orchestra is divided into three individually-conducted ensembles. Meanwhile in Italy, Berio was conducting his own experiments. These included Allelujah I and Allelujah II, where the orchestra was arranged into six and five groups respectively, and Tempi concertati, in which a solo flautist moved between four chamber ensembles.

Characteristically unhappy with the initial results of these projects, Berio began working on the Quaderni, or “notebook” pieces. Instead of breaking an orchestra into separate units, he redistributed the instruments into new configurations within the orchestra, then wrote music that took advantage of their timbral juxtapositions. Each “notebook” has a different focus, but all rely on thick clusters of sound, harmonic fields and sonic aggregates that alternate between brief, crackling exchanges and overwhelming crescendos. Most are between 5-6 minutes long.

These “notebooks” were released in three separate configurations from 1959-1962: Quaderni I, Quaderni II, and Quaderni III. But even as Berio was publishing these pieces, he was already re-conceiving them as part of a larger, more integrated whole, an alternating sequence of dissonant orchestral pieces and more melodic vocal pieces. Inspired by James Joyce, Berio referred to the vocal pieces as “epiphanies,” which became the name of the entire work—Epifanie. (Epifanie is the plural of the Italian word epifania.)

Working with Umberto Eco, Berio selected a series of texts for his various “epiphanies.” The authors naturally included James Joyce—whom Berio had already honored with Chamber Music (1953) and Thema (1958)—but also Modernist poet T.S. Eliot, French novelists Marcel Proust and Claude Simon, Spanish poet Antonio Machado, and German playwright Bertolt Brecht. The style of each setting varied, informed by internal textual cues as well as external musical relationships. Some vocal pieces were poetic recitations, others traditional songs, and some operatic arias. The revised Quaderni were demoted to “orchestra pieces,” each given an alphabetical designation, “A” through “G.” The five “vocal pieces” were assigned lower-case letters, “a” through “e.” (Some of the selected texts did not receive letters, and were intended to be recited over the orchestral pieces.)

Keeping in the spirit of the “open work,” Umberto Eco suggested the twelve pieces of Epifanie should possess a variable order, somewhat like Pierre Boulez’ Third Piano Sonata of 1958. Berio agreed, but restricted the possible variations to nine “alliterations” based on logical relationships between the individual works. (While this may have pleased Eco, in practice Berio considered his original arrangement the superior one, and never again returned to a choose-your-own-adventure style of composition. Also, various sources have described the number of alliterations as 10 or even 12, but Berio’s biographer David Osmond-Smith gives the number as 9, as does Bálint András Varga.)

Epifanie premièred at the Donaueschingen Festival for contemporary music in 1961. Berio withdrew the piece and published a revised version in 1965. This revision struck the line from Eliot, added a recitation of a poem by Edoardo Sanguineti, and included additional orchestral accompaniment for the Joyce setting. In 1991, Berio deciding to finally “close” his open work. He permanently fixed the sequence and made a few changes to orchestration. He also renamed the piece Epiphanies. This “final” version was premièred in Philadelphia in 1993, with Charlotte Hellekant as soprano.

Listening to Epifanie

Even though the 1965 Epifanie has been replaced with the 1991 Epiphanies, all three recordings of the piece date from 1969-1974, so the 1965 version is the most commonly heard and discussed. It’s also, in my opinion, better—more aggressive and demanding. I also like the fact it’s an open work—hardly a surprise, given that I once ran an Umberto Eco site! So that’s the version discussed below.

Whether one knows its tangled history or the internal relationships between its pieces, Epifanie is a remarkable work that establishes a dense, sonic world of its own. The orchestral pieces—the former Quaderni—are knotty clusters of sound that assault the ears with blaring horns, breakneck xylophone runs, and sudden thwocks of charged percussion. These clusters of orchestration are connected by a trembling tissue of musical pointillism, individual instruments firing like nerves before the next convulsive surge. But like all Berio’s work, repeated listening reveals patterns in the roiling magma. Not all is chaos, and a sense of mysterious order provides a propulsive tension lacking from purely aleatory works.

Of course, the highlights of Epifanie are the melodic epiphanies themselves, each song emerging from the atonal tempest like a welcome island—perhaps not a tropical oasis, but a safe haven with firm land and drinkable water. It’s a ridiculously challenging role for the soprano, who must speak five different languages, employ several virtuoso techniques, and express a wide range of musical moods. As of this writing, the only commercially recorded versions of Epifanie feature the peerless Cathy Berberian, whose command of Berio’s fiendish writing feels like a defiant act of passion. (Seriously—just go to minute marker 14:09 of this 1969 recording and follow along with the score. Trust me, you don’t need to read music!)

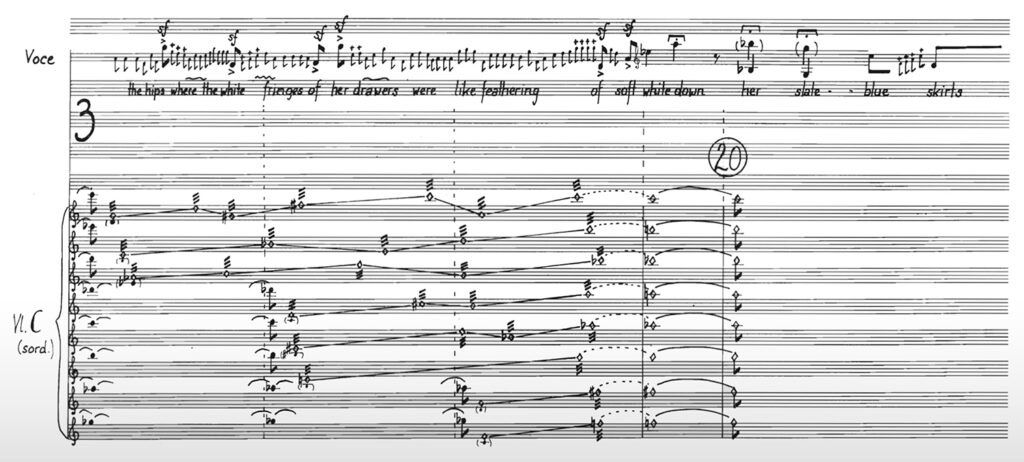

Excerpt from “Epifanie” score. The notes with + signs are “nota batutta.”

Excerpt from “Epifanie” score. The notes with + signs are “nota batutta.”

All the vocal pieces are excellent, but the Joycean setting is given pride of place—as might be expected in a work named after his most celebrated trope. Epifanie d is the song “A girl stood before him,” with text adapted from Chapter IV of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. This remarkable “madrigal” demands a virtuoso performance that incorporates everything from actual birdsong to antiquated nota battuta trilling inspired by Monteverdi. Again Berberian rises to the occasion, a bravura performance that alternates between spoken word, opera, and laughter. Even the orchestra falls into a reverent hush, her only accompaniment a sustained tension from a “third group” of violins at the rear of the stage.

The Joyce song is flanked (on either side, depending on the alliteration) by Epifanie E: “Orchestra Piece with Spoken Interjections,” a particularly bracing “notebook” composed of overlapping brass and thundering percussion. As the piece builds in intensity, the soprano exclaims a line not from Portrait, but from Ulysses, drawn from Stephen’s asymmetrical exchange with Mr. Deasy: “That is God! Hooray! Ay! Whrrwhee! A shout in the street!” As shouted by Cathy Berberian, it’s never sounded more defiantly joyous.

When taken in Berio’s preferred order—or when played as Epiphanies—the final vocal piece is a line from Bertolt Brecht’s poem, An die Nachgeborenen:

Was sind das für Zeiten, wo

Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist

Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele Untaten einschließt!

What times are these, in which

A conversation about trees is almost a crime

For in doing so we maintain our silence about so much wrongdoing!

Described by Berio as a “kick in the stomach,” the stanza articulates a sentiment that would be voiced in many Berio compositions to come, including Sinfonia and Coro.

Although Berio’s insistence upon the special state triggered by bombarding perception with a richer range of stimuli that in can fully cope with carries no metaphysical implications, it challenges the narrowly focused and controlled mode of attention which the adult individual in our culture is encouraged to identify with “self”-preservation.

—David Osmond-Smith, writing on “Epifanie” in 1998

Liner Notes from Epifanie and Folk Songs

By Paul Moor & Luciano Berio

Epifanie and Folk Songs

RCA, 1971

In Italian an epifania (plural: epifanie, with both forms accented on the second “i”) indicates a sudden spiritual manifestation. Luciano Berio composed his Epifanie between 1960 and 1963, the revised version recorded here dates from 1965. Berio stipulates the possibility of performing the seven short orchestra pieces and the five vocal pieces in ten different sequences. When the American premiere of Epifanie took place in Chicago on July 23, 1967, Berio had this to say about it:

Epifanie is, in essence, a cycle of orchestral pieces into which a cycle of vocals pieces has been interpolated. The two ‘cycles’ can be combined in various ways; they can also be performed separately. The texts of the vocal pieces have been taken from Proust (À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs), Antonio Machado (Nuevas Canciones), Joyce (A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses), Edoardo Sanguineti (Triperuno), Claude Simon (La route des Flandres), and Brecht (An die Nachgeborenen).

The significant connection between the vocals pieces can thus appear in different lights according to their position in the instrumental development. The chosen order will emphasize the apparent heterogeneity of the texts or their dialectic unity. The texts are arranged in such a way as to suggest a gradual passage from a lyric transfiguration of reality (Proust, Machado, Joyce) to a disenchanted acknowledgment of things (Simon; for this text the voice speaks and becomes gradually nullified by the orchestra). Lastly, the words of Bertolt Brecht, which have nothing to do with the epiphany of words and visions. They are the cry of regret and anguish with which Brecht warns us that often it is necessary to renounce the seduction of words when they sound like an invitation to forget our links to a world constructed by our own acts.

The score calls for an unusually large orchestra: 16 woodwinds; 6 horns, 4 trumpets and 4 trombones plus tuba, full strings, including three violin sections, and a percussion section calling for a number of performers who address themselves not only to glockenspiel, celesta, vibraphone and marimba but also to spring coils, tam-tam, tom-tom, temple blocks, wood blocks, caisse claire, bongos, timpani, cowbells, tubular bells, chimes, claves, guiro, censerros, cymbals, snare drum, tambourine, etc., etc.

Program Notes from the 1974 Salzburg Festival

By Lothar Knessl

Scored for mezzo-soprano and large orchestra, this piece grew out of Quaderni I and II for orchestra alone, the ten sections of which can be assembled by the conductor in various ways. In the case of Epifanie, which can be performed under this title only if it includes the vocal sections, twelve different combinations are possible, and these are indicated by the composer in the score.

The words are a montage of quotations based on an idea by Umberto Eco and are taken from Proust’ L’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses, Antonio Machado’s Nuevas Canciones, Claude Simon’s La Route des Flandres and a number of texts by Brecht: other texts are interpolated at various points in the score. The performer can choose whether some of these texts are synchronized with the instrumental writing at different points in the work. In other words, the relationship between the text and the context in which it is placed by the interpreter is variable.

Berio himself has explained that “the meaning of the words and their vocal expression can always appear in a new and unexpected light. At the same time the meaning of the text is not always confirmed by the developing instrumental writing. But when it is confirmed (the listener often expects only this confirmation, which is why I prefer not to indicate the texts), the onomatopoeic qualities of the texts are also structurally exploited.”

In Epifanie the vocal writing is not more important than the instrumental sonorities. None the less, the texts are ordered in such a way in performance that they give the impression of a gradual transition from a poetic, lyrical mood to an increasingly “demystified,” objective account of things.

Excerpt from Oxford Studies of Composers: Berio

By David Osmond-Smith

Oxford Studies of Composers: Berio

Oxford University Press, 1991

If Berio was to achieve differentiation between complex sound-layers within a unified orchestra, he had to rely upon homogeneity of timbre within a given layer. He provided himself with the basic materials for this by rationalizing his orchestra. Where in Allelujah II there had been a flute quartet, and indeed complementary horn quartets and trumpet trios placed in different groups, now in the Quaderni all wind families were organized in groups of four (save for six horns and a single tuba), and strings in groups of eight (save for six double-basses). Berio demanded three groups of violins, the third of which was to be placed around the back of the orchestra to act as a form of echo chamber, allowing specific harmonic configurations that had been established in the foreground to become a background layer for others. The orchestra for the Quaderni was completed by a rich selection of pitched and unpitched percussion.

The Quaderni are above all virtuoso studies in orchestral sound—the culmination of a decade of investigation. They show a meticulous control of nuances of harmonic density, rhythm, and timbre, but as means to an end. For here more than anywhere, Berio explored the global effects of interactions between these elements. (This intensive focus upon questions of texture and density makes of the Quaderni a magnificent foil to the vocal settings of Epifanie, whose melodies appear among them as musical “epiphanies”: moments of lucidity and focus that parallel the young James Joyce’s literary conception.) Thus the huge harmonic aggregates, in part chromatically saturated and covering much of the orchestral gamut, that Berio uses as staccato punctuation marks or as massive sound-blocks, demand new forms of differentiation from the ear. In part, they can be distinguished by the placing of ‘windows’ at different registers within the saturated blocks. But, more importantly, they emphasize the range of possibilities at work in an orchestral tutti. At one extreme, these aggregates are layered, so that instruments of similar timbre play adjacent notes within them. At the other, they are fully integrated by dispersing instruments of the same family on to non-adiacent notes. The more subtle variants between these two poles often lie at the very borderline of perception: particularly so when used as staccato attacks, as in the latter part of Epifanie C. They alternate with other ways of exploring complex musical objects that invite a greater measure of analytical listening.

Excerpt from Two Interviews

By Luciano Berio & Bálint András Varga

Two Interviews

Marion Board, 1985

Bálint András Varga: Let us return to your vocal compositions and Umberto Eco. Epifanie is an important work of the early sixties, both in its significance and its dimensions. I understand that you selected its texts partly on the advice of Eco.

Luciano Berio: As far as the text of Epifanie is concerned, Eco’s most important suggestion was to make the order of the quotations interchangeable within certain limits. The result should always suggest a process or development, if you like—based not only on the music but also on the content of the poems used. It can, for instance, start with Proust and end with Brecht: in other words, it can start out from a distant, complex and almost decadent poetic image and reach its opposite—for after all, the Brecht is like a kick in the stomach. If the order is changed, the relationship between literature and reality is explored in a more round-about way and of course the musical process is also changed. The literary quotations—more than half of which were suggested by Eco have an image in common: the tree. It can be regarded as a tribute to Brecht who, in his famous poem An die Nachgeborenen which is used in Epifanie, reminds us of those hard times when talking about trees becomes a sin because it means keeping silent about tragedies and injustices.

V: For the recording of Epifanie, you selected the first of the nine possible orders.

B: Yes, that is the one I like most. The possibilities are also based on musical considerations: there is a harmonic alliteration between the end of one piece and the beginning of another—in other words, the same thing is continued in a different context.

V: Do you like the original version, too, where the three Quaderni are performed without the vocal part?

B: I have not heard it for a long time. Epifanie is the one that I feel closest to. We can actually regard the piece as two cycles—one vocal, one orchestral—which are performed simultaneously. The vocal cycle appears as an epiphany, that is, as a kind of sudden apparition, in the more complex orchestral texture.

V. The title and perhaps the very notion of the epiphany were presumably suggested by Joyce, who explains its meaning in his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man?

B: That’s right. The Portrait suggested one of the episodes in Epifanie, too; the apparition of the girl who is like a sea-bird.

V: The music of that episode is like a folk song—it is very erotic, very human, while the vocal writing of some of the other movements seems to me rather neutral, almost synthetic.

B: Epifanie is a very diversified work. The “vocal cycle” in particular covers a wide range of vocal expressions, and techniques. By comparison the “orchestral cycle” is very unified.

V: Why do you use the nota battuta in the Joyce episode?

B: For descriptive and expressive reasons, the subject being a “girl-bird’: you could call it a “madrigalism”. But also because that technique has fallen into oblivion, as have so many others: I taught it to Cathy and she mastered it extremely well.

Excerpt from an Interview with Cathy Berberian

By Bálint András Varga

From Boulanger to Stockhausen: Interviews and a Memoir

University of Rochester Press, 2013

Bálint András Varga: Did you ever suggest a vocal effect [to Berio]?

Cathy Berberian: It occurred very rarely. With the exception of Folk Songs, new effects were always his invention and he would ask me to try them out.

BAV: For example?

CB: In 1963, when he was composing Epifanie, he needed a particular effect, the nota battuta that occurs in many of Monteverdi’s compositions. [Vargas Note: Nota battuta denotes the increasingly rapid repetition of a tone. Nowadays it is often called, in English, “trillo.”] You know what I mean (demonstrates it). Well, that is nota battuta. I had never sung Monteverdi before because the Italians told me my voice was not suited to it. I believed them—in those years I was very obedient, I had little faith in myself. Luciano asked me to see if I could do it. He never told me it had anything to do with Monteverdi. “Try it!” he said. I did. “You sound like a lamb, you are bleating.” I had another go at it. “Now you sound as if you were having a stomachache.” I tried again. And suddenly there it was—I made it. Berio said: “That’s it! Keep it!”

That was how I learned to sing nota battuta; it is not easy.

I also showed him an effect which he actually ended up using in Epifanie. I do not get it each time, for I do not know myself how I do it. It is an odd sort of hooting sound. I usually say it comes from the top of my head. I showed it to him, he liked it and put it in the piece.

When he was composing Circles in Massachusetts, we had a bird coming every afternoon and landing on our windowsill. (She imitates the bird-song.) We looked at each other, and it ended up in Epifanie as well. All in all, it is difficult to define how my influence on him worked. He heard me sing all the time and egged me on and on. And I did my best to go as far as my abilities let me.

BAV: It is like discovering a new instrument.

CB: Luciano is Italian and the voice is not only an integral part of Italian music, it is also part and parcel of Italian life. In Italy, people live on an operatic plane. Everything is on a heightened level. In the theater, a simple social comedy becomes transformed into a bloody tragedy. Nobody talks “normally.” Instead of saying, “Will you please pass me the ashtray,” they go (she demonstrates it by repeating the words fortissimo and gesticulating). For Italians, then, the voice is of central significance. Luciano, of course, loves opera—Verdi, Puccini. He also lectures on it. However, Monteverdi is closest to him.

BAV: And you, having inspired quite a range of composers, decided to try your hand at it yourself.

CB: You mean Stripsody? It all started out from the fact that I adore comic strips—you know, what I mean? Those series of comic drawings. Not that they are always funny. They can be very serious indeed. I know of philosophers who study them.

I once conceived of the idea of collecting the onomatopoeic noises that appear in the strips (shows some). I thought it would be fun to make a piece out of them. That is what I did: I collected those sounds and arranged them in a particular order. Originally, I thought I would pass on that “text” to a composer. First, however, I performed it for the Italian philosopher Umberto Eco. When I finished, he said: “But you have the piece! Why should it be composed?” “Oh no!” I said. I could not believe it. “But of course!” he insisted. “It is the funniest thing I have ever heard!”

Excerpt from “Music After Joyce: The Post-Serial Avant-Garde,” By Timothy S. Murphy

By Timothy S. Murphy

“Music After Joyce: The Post-Serial Avant-Garde”

Hypermedia Joyce Studies, Volume 2, Number 1. Summer 1999.

In Thema, Berio claims, “we pass from a ‘poetic’ listening space to a ‘musical’ listening space. This musical listening space is based on the poetic material, on an object which is transformed and becomes music” (Berio, “Entretien” 63). Berio’s most recent directly Joycean work, Epifanie (1959-61), also uses “the voices of poets to make music” as Eco says, but in a very different way than Thema did. First of all, despite the Joycean title, he does not limit himself to Joyce’s writing, but works with a variety of texts in five languages. In addition to the bird-girl passage from chapter IV of Portrait, Berio also uses Brecht’s poem “An die Nachgeborenen,” a passage from Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu, and texts by Machado, Sanguineti and Claude Simon. He does not transform the words through tape manipulation, but simply sets them to music that moves from tonality through free atonality to serialism and back with grace and clarity. The true novelty of Epifanie for Berio, however, lies in its large-scale structure, which is reminiscent of Boulez’s Third Piano Sonata: it is an open-form work, though one that is fully composed like Boulez’s rather than indeterminate like Cage’s. Epifanie consists of seven orchestral sections divided into three “Quaderni” or “Notebooks,” and five orchestral song segments, labeled “a” through “e.” These twelve elements, which comprise “two cycles—one vocal, one orchestral—which are performed simultaneously” with the vocal cycle acting as “an epiphany, that is, as a kind of sudden apparition, in the more complex orchestral structure” (Berio, Two Interviews 147), can be arranged in ten different ways, according to Berio’s instructions in the score (Berio, Epifanie notes), this number of arrangements being defined by his insistence that “The result should always suggest a process or development…based not only on the music but also on the content of the poems used” (Berio, Two Interviews 146). The Joyce passage, for example, which is set in “madrigal” fashion to an accompaniment of violins, cannot begin the vocal cycle of the work, but it can conclude it. In this rather Boulezian manner, Berio too resolves the apparent contradiction between authorial control and openness of form that drove the Darmstadt group’s aesthetics by inserting points of choice or responsibility for the performer into a fully composed work.

Though he has not returned to direct work with Joyce’s texts since Epifanie, Berio has continued to be profoundly influenced by them. David Osmond-Smith, the leading scholar of Berio’s work, claims that the experiment of Thema “provided a basis for the treatment of Dante in [Berio’s] Laborintus II (1965) and of [Beckett and] Lévi-Strauss in Sinfonia (1968-69),” and further that “it was in the major instrumental works of the Sixties that Berio really arrived at more general Joycean working methods” (Osmond-Smith 84, my translation). Osmond-Smith likens Berio’s method of elaborating the solo Sequenza VI (1967) for viola into the concerto-like Chemins II (1967), IIb and III (1968) to the procedure of “stratification” that Joyce used to elaborate the originally rather conventional language of Finnegans Wake into its final hyper-determination. “If the stratification process of Finnegans Wake suggests…self-perpetuation, then the many proliferations from Sequenza VI for viola insist on the temporary nature of creative solutions, and demand from listeners and readers of the score, not passive consumption, but active criticism” (Osmond-Smith 88, my translation). The circular phonemic structure of the a capella vocal work A-Ronne (1974-75) as well testifies to a continuing debt to Finnegans Wake, which Berio once described as manifesting a “richness of relations…so complex that the reader gives a new interpretation at each reading, discovering not only allusive bonds, but also a continually changing concrete reality” (Berio, “Forme” 39). This debt also remains evident in his later vocal and operatic collaborations with Edoardo Sanguineti and Italo Calvino.

Review of Epifanie

By Misha Donat

“Review of Berio Conducts His Epfanie and Folk Songs”

Tempo, Number 1o1, 1972, pp. 57-59

I am reprinting this 50-year old review of the 1971 recording of Epifanie because Donat offers some insightful analysis into the piece and its history. You can listen to the actual recording under review at the Internet Archive.

In his 1965 revision of Epifanie, Berio extended his happy collaboration with Sanguineti (who also wrote the text of Berio’s ‘messa in scena’, Passaggio) by adding a section setting part of his Triperuno. But the initial impetus behind Epifanie came from another prominent member of the Novissimi group of writers, Umberto Eco. An acknowledged authority on Joyce, and the author of an important treatise on ‘Open Form’, it was Eco who was largely responsible for the original selection of the texts of Epifanie (taken from Proust, Machado, Joyce, Simon and Brecht). Several years ago, while the score was still in progress, Berio in conversation referred to Epifanie as a sort of notebook to which he hoped to contribute further entries from time to time. Despite the brilliance of many of its notes, one cannot help feeling that loose-leaf character. Significantly, it’s the only one of Berio’s major works which gives a list of alternatives for the order of performance of its large-scale sections: for all his lifelong fascination with Joyce, Berio is not a composer whose work is normally characterized by any principles of ‘open form’—indeed, his fondness for recapitulatory codas frequently gives his music a far more ‘closed’ quality than that of many of his contemporaries. Characteristically, Berio has felt the need to add to his Sinfonia a fifth movement that resolves the material of the preceding sections into what one might call a ‘provisionally final’ ending. Again, although the whispering voices which end Laborintus II sound an entirely new note of optimism (the text refers to the ‘sleeping children’ who will presumably awake to a better world), the remainder of the final section is largely concerned with recalling material from the first part of the work.

If Epifanie seems to lack a final resolution, whatever chosen sequence of performance of its parts, the work as a whole is not quite as sectional as a glance at the ten alternative orderings of its twelve pieces might lead one to suppose. Several of the pieces are in fact linked together in a manner which some of the approved orderings surprisingly fail to take into account. The sustained C natural with which the voice ends the Brecht setting, for instance, is taken over by the clarinet at the opening of the orchestral piece which in this recording is placed last. Yet in only half of Berio’s given sequences are these two pieces placed together. Again, three of the optional orderings ignore the solo cello note which is tied over from the orchestral piece designated ‘A’ to the start of the Proust setting. In this recording, the sequence used is the one that heads Berio’s list in the printed score; it was this arrangement, too, that was used in the Royal Festival Hall performance of the work in March 1970. Berio has said of this version that its texts suggest

a gradual passage from a lyrical transfiguration of reality (Proust, Machado, Joyce) to a disenchanted acknowledgement of things (Claude Simon: for this text the oice speaks and becomes gradually nullified by the orchestra). Lastly, the words of Bertolt Brecht, which have nothing to do with the epiphany of words and visions. They are the cry of regret and anguish with which Brecht warns us that often it is necessary to renounce the seduction of words when they sound like an invitation to forget our links to a world constructed by our own acts.

Although the textural progression of this version of Epifanie seems clear and logical enough, there remains the marked sections—most of which are heavily scored—and the vocal passages, which generally have the lightest of instrumental accompaniments. That Berio was conscious of a dichotomy here is shown by his attempting to smooth it over, to some extent, through the inclusion of a spoken text during dome of the otherwise non-vocal sections. Even so, the undeniable lack of dramatic coherence between these two types of section betrays their origins as separate works, and it’s not surprising that Berio allows for separate performance of the orchestral pieces in various combinations. In view of the danger of hearing the orchestral pieces of Epifanie as direct commentaries on the sung texts, it is interesting that the composer has now dropped the shouted quotation from The Waste Land (‘I will show you fear in a handful of dust’) which originally motivated the violent orchestral piece that in the RCA recording stands at the center of the work.

Cathy Berberian’s performance of Epifanie is, of course, unique, and is well reproduced on this record; Berio has also managed to procure a really first class performance from the BBC Symphony Orchestra… In Epifanie, however, the close-up sound tends occasionally to rob the music of any genuine pianissimo: the passage from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, for instance, is accompanied only by a line of violins placed at the back of the stage (this third violin section is a favourite device of Berio’s, and one he also uses in Laborintus II and Sinfonia). In the unpublished 1961 version of the score this entire passage was, in fact, sung unaccompanied, and it’s clear that even with its very effective revised scoring, the strings should provide only a very distant halo to the voice, and not a crystal-clear foreground element as here. But this is a very small point, and one which in no way lessens one’s gratitude to RCA for issuing these two important records.

Texts

Epifanie

Part 6: Epifanie E: Orchestra Piece with Spoken Interjections

— That is God.

Hooray! Ay! Whrrwhee!

— What?

— A shout in the street

Part 7: Epifanie d: “A girl stood before him” (James Joyce)

A girl stood before him in midstream alone and still gazing out to sea she seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird her long slender, bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh her thigs[sic] fuller and soft hued as ivory were bared almost to the hips where the white fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down her slateblue skirts were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her her bosom was a bird’s soft and slight slight and soft as the breast of some dark plumaged dove but her long hair was gerlish[sic] and girlish and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty her face.

Original Joyce Text: From the “Nestor” Episode of Ulysses

From the playfield the boys raised a shout. A whirring whistle: goal. What if that nightmare gave you a back kick?

— The ways of the Creator are not our ways, Mr Deasy said. All human history moves towards one great goal, the manifestation of God.

Stephen jerked his thumb towards the window, saying:

— That is God.

Hooray! Ay! Whrrwhee!

— What? Mr Deasy asked.

— A shout in the street, Stephen answered, shrugging his shoulders.

Original Joyce Text: From Chapter IV of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

A girl stood before him in midstream, alone and still, gazing out to sea. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. Her thighs, fuller and softhued as ivory, were bared almost to the hips, where the white fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down. Her slateblue skirts were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her. Her bosom was as a bird’s, soft and slight, slight and soft as the breast of some darkplumaged dove. But her long fair hair was girlish: and girlish, and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face.

Recordings

Three individual recordings of Epifanie have been commercially released. The following lists them in order of performance/recording date, not publication date.

Berio: Epifanie (1969)

Conductor: Luciano Berio

Musicians: Orchestra RAI di Roma

Soprano: Cathy Berberian

CD: La Nuova Musica Vol. 3: Berio, Cage, Pousseur. Stradivarius STR 10017 (1989)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube

Released in 1989, this Italian CD features a live recording of Berio conducting Epifanie in Rome on 15 March 1969. Long since deleted, used copies are excruciating rare, but thankfully it’s been digitized on YouTube. Even better, the accompanying video lets you follow along in the score, which is quite an experience. The 1969 recording is the inferior of the three, but it’s worth hearing Berio conduct a live performance.

Berio: Epifanie (1971)

Conductor: Luciano Berio

Musicians: BBC Symphony Orchestra

Soprano: Cathy Berberian

LP: Luciano Berio Conducts His Epifanie and Folk Songs. RCA Red Seal LSC-3189 (1971)

Purchase: LP [Amazon], Digital [Internet Archive]

Conducted by Berio in the BBC studios, London, this is a searing version of Epifanie, with each instrument clearly delineated and the percussion placed front-and-center in the soundfield. The production is so distinct, it feels like an audio X-ray of the former Quaderni. Unfortunately, Cathy Berberian is not miked as closely, and occasionally seems overwhelmed in the mix—not an easy thing to do with her voice! Still, she sings beautifully, with tremendous agility and power, even when competing with danger-close percussion and intrusive strings. While Berberian’s vocals are more distinct on the 1974 Salzburg recording, the orchestration on this LP is superior, making both copies essential. Happily, some kind soul has liberated this LP from the used record bin and digitized it on the Internet Archive. Even through a half-century of dust, scratches, and pops, the music shines through brilliantly. (This is the record reviewed by Misha Donat above.)

Berio: Epifanie (1974)

Conductor: Leif Segerstam

Musicians: OFR Symphonieorchester

Soprano: Cathy Berberian

CD: Epifanie & Coro. Orfeo C 626 041 B (2004)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube

This CD collects two performances of Berio’s work from the Salzburg Music Festival, with Epifanie dating from 19 August 1974. It’s a live recording drawn from the Salzburg archives and cleaned up for CD, so the sound quality is somewhat uneven. While Cathy Berberian comes across beautifully, the orchestra can sound muddy, especially during the denser sections. It’s not terrible; but the RCA recording offers a better showcase for these former Quaderni. Also, the BBC Symphony Orchestra had the benefit of Berio himself conducting, and they seem more dedicated to the nuances of his complex score. Finally, the Orfeo liner notes are a mess. Written for a German audience, not all the European languages are translated into English, and the libretti are poorly organized. Nothing worthwhile has been included about the performance of Epifanie; just some recycled quotes from contemporary accounts. There’s also a curiously defensive essay about Salzburg’s relationship to contemporary music, pages that could have been used for a more useful analysis—which alliteration of Epifanie was used? Why were those selections made above others? And so forth.

Online Video

The following live performances are available on YouTube.

Epiphanies

Conductor: Roberto Abbado; Soprano: Valentina Coladonato

Recorded on 5 October 2013, this performance of the 1991 Epiphanies features Roberto Abbado conducting the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna. Abbado does a great job and the orchestra plays well, but the performance feels tame when compared to previous recordings. Mezzo-soprano Valentina Coladonato gives it her all, even if she can’t quite match the dizzying virtuosity of Berberian’s performance. (To be fair, very few people can compete with Berberian, who also had Berio riding her ass the entire time!) Still, it’s great to see the piece played at all, and it’s always interesting to watch the musicians navigating the “wandering rocks” of Berio’s challenging score—those “flutter-tongued” flutes are something else.

Additional Information

Naftali Golomb’s Luciano Berio’s Epiphany

Painted in 1986 by Israeli artist Naftali Golomb, this work is for sale at Artsy.com.

Luciano Berio: Other Joyce-Related Works

Luciano Berio Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Luciano Berio profile.

Chamber Music (1953)

Three songs adapted from Joyce’s poetry.

Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958)

An electronic transformation of the opening text from the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses read by Cathy Berberian.

Traces (1964)

Only given one performance and withdrawn, this “ghost opera” about racism was partially inspired by the “Circe” episode of Ulysses.

Sinfonia (1968/69)

This tour de force of music, voice, and sound incorporates text from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable. While it has no overt Joycean references, Sinfonia is frequently compared to Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

A-Ronne (1974/75)

A “documentary” on a poem by Edoardo Sanguineti, this piece of vocal virtuosity contains a reference to Finnegans Wake.

Outis (1996)

Berio’s opera about the transformations of Odysseus includes material borrowed from Joyce’s Ulysses.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com