Joyce Music – Berio: A-Ronne

- At December 20, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

“…this is not a composition in the normal sense of that word…”

—Luciano Berio on “A-Ronne”

“…this is nat language in any sinse of the world…”

—“Finnegans Wake” 83.10-12

A-Ronne

(1974/1975)

Version 1: “Radiophonic documentary” for five actors

Version 2: For eight singers

The Commission

In 1974, Frans van Rossum and Jan Starink of Kotholieke Radio Omroep in the Netherlands commissioned a radio piece from Luciano Berio. The composer responded with a novel idea—a “radiophonic documentary” on a poem in honor of the 50th anniversary of André Breton’s Manifeste du surréalisme. This “documentary” would employ five actors to interpret the poem in various styles, from an angry tirade to a romantic exchange. Meaning would be found less in the content of the poem as in the expression of the poem. Like the distorted reading of “Sirens” in Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), the boundaries between language, music, and sound would be blurred beyond recognition.

Berio turned to his friend and frequent collaborator Edoardo Sanguineti, the Italian poet who had provided the text for five of Berio’s previous projects—Passaggio, Esposizione, Traces, Laborintus II, and Epifanie. The two discussed the parameters of the poem over the telephone: the poem should be composed of short sentences which could be broken into segments, and the text should emphasize alliteration and onomatopoeia. Two days later, Sanguineti sent Berio “A-Ronne.”

Berio’s “radiophonic documentary” was produced at the studios of Radio Hilversum and aired on 30 June 1974. A year later, Berio created a version for the stage, replacing the actors with five singers. This was followed by A-Ronne for eight singers, dedicated to Ward Swingle and arranged for the Swingle II Singers: two sopranos, two altos, two tenors, and two basses. (Swingle’s famous octet had been associated with Berio since the première of Sinfonia in 1968.) This final version of A-Ronne premièred at Liège in 1974, and remains the one most often performed in concert.

So Which Version Are We Discussing?

Whenever discussing A-Ronne, a writer must specify which version is under discussion. There are two published scores for A-Ronne, the 1974 version for five actors (UE 19329) and the 1975 version for eight singers (UE 31679). The following discussion centers on the 1975 A-Ronne for eight singers. The reason is simple—I like it better than the “spoken” version. Having said that, most of the following commentary applies to both versions; while the style of expression changes, the substance remains the same. They are similar “documentaries” of Sanguineti’s poem.

Luciano Berio in 1974 at Hilversum Radio

Luciano Berio in 1974 at Hilversum Radio

Photo by Gisela Bauknecht, from Centro Studi Luciano Berio

The Poem

Sanguineti’s poem bears many of his characteristic devices: it’s composed of fragments connected by colons, and contains quotations and allusions in several different languages. The general theme is narrative time, which is reflected in both the structure and the content of the poem. “A-Ronne” contains three “self-aware” stanzas: a beginning, a middle, and an end. Each stanza is composed of fragments that express a thematic connection to their place in this hierarchy—the quotations literally recall beginnings, middles, and endings. This narrative arc is complicated by suggestions that time is actually cyclical—like the Viconian ricorsos that drive Finnegans Wake, every ending contains the seeds of a subsequent beginning.

I.

a: ah: ha: hamm: anfang:

in: in principio: nel mio

principio:

am anfang: in my beginning:

ach: in principio erat

das wort: en arké en:

verbum: am anfang war: in principio

erat: der sinn: caro: nel mio principio: o logos: è la mia

carne:

am anfang war: in principio: die kraft:

die tat:

nel mio principio:

II.

nel mezzo: in medio:

où commence le corps humain?

nel mio mezzo: où commence?: nel mio corpo:

nel mezzo: nel mezzo del cammino: nel mezzo

della mia carne:

car la bouche est le commencement:

nel mio principio

è la mia bocca: parce qu’il y a opposition: paradigme:

la bouche:

l’anus:

in my beginning: aleph: is my end:

ein gespenst geht um:

III.

l’uomo ha un centro: qui est le sexe:

en meso en: le phallus:

nel mio centro è il mio corpo:

nel mio principio è la mia parola: nel mio

centro è la mia bocca: nella mia fine: am ende:

in my end: run: in my

beginning:

l’âme du mort sort par le pied:

par l’anus: nella mia fine

war das wort:

in my end is my music:

ette, conne, ronne:

The Quotations

Appropriately for a piece commissioned by Catholic radio, many of Sanguineti’s quotations are drawn from the Gospel of John, particularly the opening line: “In the beginning was the Word.” This is rendered in Latin as “In principio erat verbum,” and in the Greek as “En arké en o logos,” a transliteration of ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος. Along with these antique languages we find Martin Luther’s German translation, “Im Anfang war das Wort.” Sanguineti quotes from the Gospel of John a second time with “et verbum caro factum est,” or “and the Word became flesh.” (Note that Sanguineti’s poem omits capitalization, whether grammatical or liturgical.)

These Biblical quotations reverberate with ironic echoes, such as the Italian translation of caro as carne, or “meat.” Sanguineti includes three substitutions of “Logos” from Goethe, where Faust considers replacing Wort (Word) with Kraft (Power), Sinn (Sense), or Tat (Deed). Even more provocatively, rather than rendering the famous verse in English, Sanguineti quotes T.S. Eliot’ poem “East Coker” from Four Quartets. Eliot’s poem personally embodies the Logos, opening with “In my beginning is my end” and concluding with “In my end is my beginning.”

Sanguineti moves even further from the sacred to the profane with a quote from “Outcomes of the Text,” a Roland Barthes essay about George Bataille’s “The Big Toe.” In a section of the essay named Commencement, Barthes writes,

The “beginning” is a rhetorician’s notion: How to begin a discourse? For centuries, the problem has been argued. Bataille asks the question about beginning in an area where it had never been asked before: where does the human body begin? [“où commence le corps humain?”] The animal begins by the mouth: “The mouth is the beginning, or, if one prefers, the prow of animals… But man does not have a simple architecture like beasts, and it is not even possible to say where it begins.” This raises the question of the body’s meaning…When the human body is the subject of psychoanalytic discourse, there is a semanticization (“meaning”) because there is a paradigm, opposition of two “terms”: mouth [la bouche] and anus [l’anus].

If la bouche and l’anus represent the beginning and end of the body, le phallus—also symbolized by Bataille’s “big toe”—represents the erotic middle. Barthes’ essay is also fascinating for its unconventional structure: a series of fragmentary “outcomes” derived from Bataille’s text, arranged in alphabetical order and loosely organized around notions of “oppositions” and “middles.”

Special mention should be made of Sanguineti’s use of paradigme. As Nina Horvath notes in her 2009 paper, “Theater of the Ear: Analyzing Berio’s Musical Documentary A-Ronne,” paradigme “is word 102 of 170, placing it at the Golden Mean of the poem.” According to the work of linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, a favorite of both Barthes and Berio, a “paradigm” is a “set of relationships a linguistic unit has with other linguistic units in the same context.” Horvath explains:

Paradigmatic relationships are in direct contrast and deal with elements that are related to the word in use but are in absentia. For example, “girl” and “girls” or “girl” and “boy” are related, but would not be used in the same context. The concept of paradigmatic or contrasting ideas appears frequently in Sanguineti’s work. In this poem, the underlying contrast opposes beginning to end.

Sanguineti’s own “middle” stanza is bracketed by a pair of famous first lines. It begins with the literary grandfather of all opening middles—“Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita”, the first line of Dante’s Inferno: “Midway through the journey of my life.” The stanza ends with the opening of the Communist Manifesto, “Ein Gespenst geht um in Europa—das Gespenst des Kommunismus.” (“A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.”) As only the first four words are used, inserted between “end” and “l’uomo” (“man”), the word that opens the next stanza, it suggests an afterlife more than a true ending, a—perhaps ironic?—continuation of Dante’s spiritual voyage.

Other literary works receive a more glancing blow. There’s a brief allusion to Beckett’s Endgame—the character “Hamm”—and the “circular sentence” that begins/ends Finnegans Wake, a snippet of “riverrun” spliced into Eliot’s poem like a computer command: “in my end: run: in my/beginning.” Because no postmodern work should be without an element of self-referentiality, Sanguineti includes a clipping from a letter he’d received from Berio about the project itself: “is my music.”

Alphabets provide additional grist for Sanguineti’s millwheeling vicociclometer. The letter “A” plays a prominent role, along with its Hebrew ancestor, Aleph. This may trigger additional literary associations, as Borges readers are sure to think of his famous story “El Aleph,” in which the Aleph becomes a symbol for “everything everywhere all at once”—to allude to a recent film that borrows Borges’ conceit. (Berio was fond of quoting the Argentine writer, and it’s hard to imagine that Sanguineti, a poet and Dante scholar, was unfamiliar with Borges.) Rather than letting Omega, Tav, or “Z” stand for the final letter of the alphabet, Sanguineti takes a page from Dr. Suess and goes “on beyond zebra,” ending his poem with three antiquated letters: ette, conne, and ronne. According to Berio’s 1974 program notes, these were the “Florentine designations” of “three abbreviations…with which in old Italian dictionaries the alphabet concluded after Z: hence the saying, no longer in use, dalla A al Ronne instead of dalla A alla Z.”

Edoardo Sanguineti in 1974 at Hilversum Radio

Edoardo Sanguineti in 1974 at Hilversum Radio

Photo by Gisela Bauknecht, from Centro Studi Luciano Berio

The Score

By this point in his career, Berio was no longer treating text as something to be simply “set” to music. In Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), he subjected Joyce’s “Sirens” to permutations based on its sonic characteristics. In O King, he dissolved Martin Luther King’s name into a cloud of phonemes. In the first movement of Sinfonia, the words of Claude Lévi-Strauss are deconstructed and shuffled at will. Even Berio’s previous collaborations with Sanguineti relied on density, allusion, and juxtaposition to produce “meaning.”

Berio’s drive towards textual experimentation reached its apotheosis with A-Ronne. Sanguineti’s text was dismembered, rearranged, and recycled to form a 30-minute “documentary” in which the basic poem is repeated over twenty times. The performers are instructed to speak, whisper, sing, scat, and shout specific passages while interpreting a variety of instructions: “like a dictator’s harangue,” “self-righteous,” “like an intimate dialogue, with a husky and hesitating tone,” “like a prompter of gas-light theatres,” “suddenly hysterical,” and so forth. Berio had done something similar to the mélange of Beckett-inspired text in the third movement of Sinfonia, but that was generally limited to adjectives—“Bewildered,” “Seductive,” “Scolding,” and so forth. These instructions were applied to text that was, on the balance, intelligible in its own right: “I must not forget this. I had not forgotten it. But I must have said this before, since I say it now.” In A-Ronne, Berio kicks away the semantic crutches and leaves the singers on their own. Sanguineti’s poem becomes raw material for a kaleidoscope of perspectives, with meaning constructed by privileging expression over content.

As Nina Horvath describes:

These vocal styles represent the “characters” in Berio’s theatre of the ear. In a theatre piece, the audience relies on visual information to distinguish characters and understand dramatic action. Berio’s theatre is exclusively aural: characters are identified by recognizable aural qualities. The vocal styles are the most distinct elements of the piece, causing the listener to associate each with a character of the drama and also generating the “local situations and different expressions” that Berio desired. By characterizing vocal styles instead of individual vocal parts or passages of text, Berio has greater compositional flexibility, since multiple voices can portray the same “character” and one passage of text can undergo multiple transformations of meaning depending on the vocal style.

Berio fortifies his “vocal styles” with a battery of paralinguistic effects, much as Cathy Berberian had done in Visage and Sequenza III—laughing, shrieking, coughing, burping, barking, chewing, and at one point, “pop-sliding finger inside-out of mouth.” These effects are interlaced throughout the text, often serving as ironic commentary or signaling major stylistic transitions.

This impish sense of humor runs throughout A-Ronne, which helps sustain its 30-minute length—in the hands of a more didactic composer, such a project could easily overstay its welcome. Instead, A-Ronne rewards repeated listening in the same way Finnegans Wake rewards repeated reading. No subsequent hearing is ever the same, and new details emerge from the babbleogue to provoke fresh “aha!” moments. Most vocal works benefit from reading along with the libretto, which trades a certain amount of musical appreciation for increased comprehension. For A-Ronne, it’s the score that offers the most enjoyment, allowing the listener to follow along with Berio’s protean commands. Hearing a truly dedicated ensemble rise to the challenge is a dizzy joy, like watching aerial acrobats working without a net. Things may seem breathtakingly chaotic, ready to fly off the rails at any moment; but this sense of pandemonium can only be created by a practiced system of control and perfect timing.

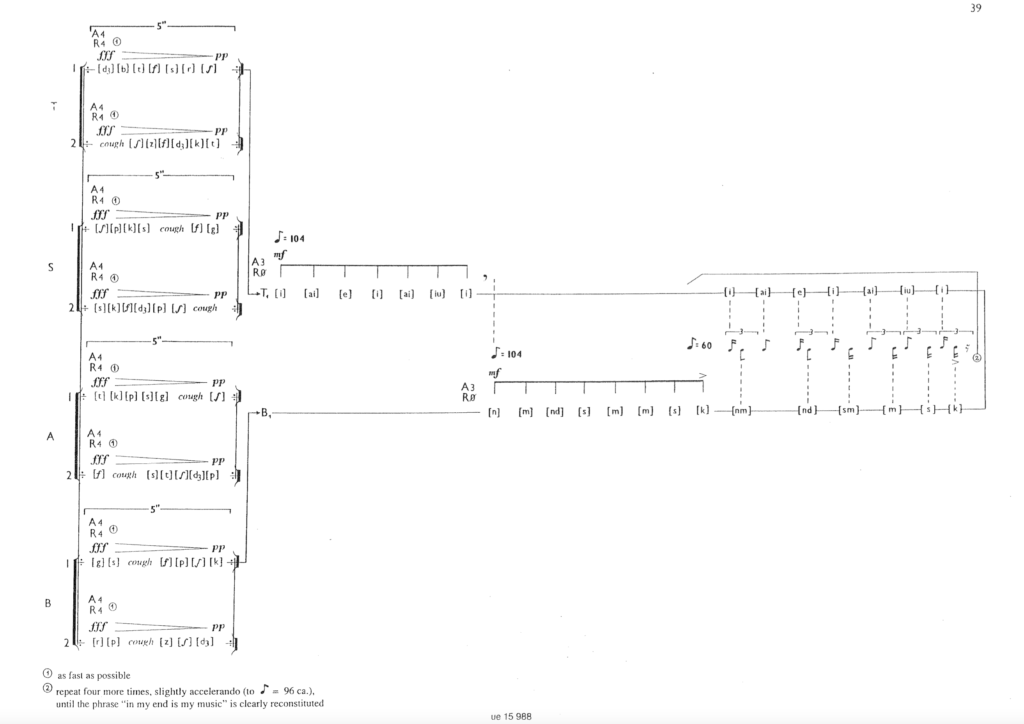

Berio’s fondness for virtuosity is most apparent during the bravura passage that revolves around the phrase “Aleph is my end.” Berio runs the line through a phonetic chromatograph, separating the vowels from the consonants. Rising to the top of the register, the vowels are sung by the first tenor, while the consonants are sung by the first baritone. These staggered rows are accelerated through repeating cycles until the phrase is “clearly reconstituted” in the listener’s ear. The effect is like the auditory equivalent of Muybridge’s horse—a flickering series of disconnected images creates the illusion of continuity. Later, the same technique is applied to the phrase “in my end is my music,” an aggregate of T.S. Eliot and Berio himself.

Score of “A-Ronne” for 8 singers

Score of “A-Ronne” for 8 singers

A-Ronne also contains moments of great beauty, even if framed by irony. For instance, the most delicate passage occurs when the sopranos, altos, and tenors sing “Ein Gespenst geht um” “liturgically” while the baritones recite the remainder of the poem “like two priests murmuring a prayer.” It’s a wonderful passage, scored with an Italian’s ear for lush sublimity. Of course, the line being beatified is from the Communist Manifesto. Berio has professed a fondness for clowns from his Ligurian youth—the trombonist’s lugubrious “Why?” in the middle of Sequenza V is a tribute to Grock—and here he tweaks multiple noses at once. One can imagine the irritation of a devout Catholic finding himself “suckered in,” as well as the humorless disapproval of a Communist hearing Marx parodied as Holy Scripture!

After A-Ronne, Berio’s next major projects were collaborations with Italo Calvino. Berio would not return to Sanguineti again until 1988 for Canticum novissimi testamenti, a “ballata” for choir. Of all their many collaborations and settings, it’s A-Ronne that remains the most popular, the work most non-Italians associate with Edoardo Sanguineti, whose challenging poetry had gone largely untranslated. Fortunately, Berio uses his words to say just about everything.

Postscript: By algebra we prove that Joyce’s grandson is Sanguineti’s grandfather and A-Ronne itself is the ghost of Finnegans Wake.

The circular phonemic structure of the a capella vocal work “A-Ronne” as well testifies to a continuing debt to “Finnegans Wake,” which Berio once described as manifesting a “richness of relations…so complex that the reader gives a new interpretation at each reading, discovering not only allusive bonds, but also a continually changing concrete reality.”

—Timothy S. Murphy, “Music After Joyce,” 1999

With its cyclical structure, multivalent allusions, and constant shifts in expression and identity, A-Ronne is Berio’s most Wakean piece, and the only one that refers to Finnegans Wake directly—the fragment “run,” clipped from “riverrun.” Also like the Wake, a foolhardy interpreter is likely to go down some very deep rabbit holes while analyzing the piece. For instance, Sanguineti only uses the word “run” once, where it directly connects an ending with a beginning, thus emphasizing the “hidden” circularity of the poem: “in my end: run: in my/beginning.” The only other word in “A-Ronne” that duplicates this function is “aleph,” which mirrors the “run” conjunction by connecting an ending to a beginning: “in my beginning: aleph: is my end.” Also of note, “run” is one of the only verbs in the poem, and the only one not originating from a longer phrase. It’s an “orphan” word, so to speak, entering the poem on its own merits. The same may be said of “aleph.”

Now, seeing as both words are only used once, and both suggest some deeper cyclical structure, it would hardly be a coincidence to note that “aleph” maps to the letter “A,” and “run” resonates with the phonetic echo of “ronne?” Making an alternate title of sorts, “Aleph to Run?” And to take this literary conspiracy theory one step further—though no further than many a PhD student has ventured when studying Joyce—to a literary mind, the word “aleph” recalls Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who famously wrote “Alph, the sacred river/ran” in his great poem “Kubla Khan.” From here, it’s not too much of a stretch to suggest that the title “A-Ronne” itself contains a trace, a ghost, an echo of riverrun, which brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Hilversum Commission Eternal?

Berio/Sanguineti double-exposure

Berio/Sanguineti double-exposure

Photo by Gisela Bauknecht, from Centro Studi Luciano Berio

Composer’s Notes (1974 Version)

By Luciano Berio

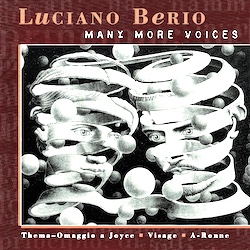

Luciano Berio: Many More Voices

BMG, 1998

The subject of A-Ronne is the elementary vocalization of a text and its transformation into something perhaps equally elementary but difficult to describe. The work, in fact, is not a musical composition in the traditional sense, even though the organizational procedures used are more often musical (for example, the use of inflections and intonations, development of alliterations and of transitions between sound and noise, and occasional use of elementary melodies, polyphonies and heterophonies). The musical sense of A-Ronne is basic, which is to say that it is common to any experience, ranging from everyday speech to theatre, where changes in expression imply and document changes in meaning. This is why I prefer to define the work as a “documentary” on a poem by Edoardo Sanguineti, as one would speak of a documentary on a painting or on an exotic country. Sanguineti’s poem, which undergoes different readings in this work, is not treated as a text to be set to music, but rather as a text to be analyzed as a generator of different vocal situations and expressions. Finally, A-Ronne is also a kind of madrigale rapprasentativo, i.e., “theatre for the ear” from the late sixteenth century in Italy, as well as a kind of vocal naïve painting. The range of given situations, no matter how extensive, can always be related to elementary situations, and to recognizable, familiar and obvious feelings; a social gathering, a speech in a square, a speech therapy session, the confessional, the barracks, the bedroom and such like.

Sanguineti’s poem is repeated about twenty times and almost always from beginning to end. It presents three themes: in the first part the theme of the Beginning, in the second part the theme of the Middle and in the third part that of the End. The poem is built strictly on quotations in various languages that extend from the beginning of the New Testament of John (in Latin and Greek), Luther’s German translation and its modifications in Goethe’s Faust, to a verse by Eliot; from a few words on an essay by Barthes on Bataille to the first letter of the alphabet (a, alpha, eleph) and to the last word which concluded the Italian alphabet in ancient times after “z” (ronne). From this came the saying “from A to Ronne,” which has long since been replaced by “from A to Z.” The poem is thus also a highly articulated and discontinuous sequence of figures of speech, which explains the frequent uses of musical figures of speech in this work. The occasional sung sections do not have an autonomous musical significance: they are moments among many others—and perhaps the simplest—in the liturgy of vocal gestures. Only the brief final section, based on a series of elementary harmonic “alliterations,” has its own musical autonomy.

Thus, the musical sense of A-Ronne is not to be found in the sung sections, but rather in the relationship that is established between a written text and a “grammar” of vocal behaviors; between a poem that is constantly faithful to its own words and a vocal articulation that continuously modifies its meaning and its referential aspects. The two levels (the written texts and the vocal behavior) always interact in different ways, and always produce new meanings. This is directly analogous to what generally happens in vocal music and in everyday speech, where the relationship between the two levels (the grammatical one and the acoustical one) is substantially responsible for the infinite possibilities of human speech and singing.

Excerpt from Two Interviews

By Luciano Berio & Bálint András Varga

Two Interviews

Marion Boyars, 1985

Bálint Andeás Varga: You have always been much involved with the human voice: when was it that you first began to experiment with it?

Luciano Berio: It was my experience with the electronic work Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) that first drew my attention to the new possibilities inherent in the human voice. In electronic music we make no distinction between human and instrumental sound: we use sound as an acoustical phenomenon regardless of its origin. Superficially, it might appear as though this would deprive it of an important characteristic—its meaning. In reality, however, exactly the opposite is the case: when analyzed, new strata of meaning come to the surface.

V: But for all that, in your vocal works you always use words, and employ vocal effects very rarely. In A-Ronne breathing, sighing and other noises do become part of the musical process, and Sequenza III is another exception. But such elements are missing in most of your vocal compositions.

B: I am not interested in sound by itself—and even less in sound effects, whether of vocal or instrumental origin. I work with words because I find new meaning in them by analyzing them acoustically and musically. I rediscover the word. As far as breathing and sighing are concerned, these are not effects but vocal gestures which also carry a meaning: they must be considered and perceived in their proper context.

A-Ronne is built entirely of stereotypes, of sounds that you can hear any day. And the text by Edoardo Sanguineti is a sequence of quotations. From a certain point of view it is a poem—I repeat it many times, emphasizing some of its lines, suggesting new meanings and new associations. Even if I treat the words neutrally in places, dismissing their meaning, the presence and the use of that particular poem is fundamental: The telephone directory would not have been suitable, even though I think it is important, occasionally, to suggest a certain indifference in relation to a text, to keep a certain musical distance from it.

The “grammar” of A-Ronne is focused on a single technique: alliteration. It is with the help of alliteration that I musically reorganize this rather complex text.

V: It is built around three subjects: beginning, middle and end.

B: Yes, and it is mostly heard in two or three languages. It was specially written by Edoardo Sanguineti. It was our only joint venture which was not the outcome of a long process of maturing and of constant dialogue and consultation. I told him over the telephone what I had in mind—short sentences which can be taken apart into small segments—and after two days I received from Sanguineti this beautiful text.

Recordings

I. Version for Five Actors (1974)

The original version of A-Ronne was recorded at the KRO studio at Hilversum in June 1974. To the best of my knowledge, that recording was never released on LP. In 1995, the tape was restored at Centro Tempo Reale in Florence and released on Luciano Berio: Many Voices. Unfortunately, that CD has long been out of print; but you can always listen to it here at the Brazen Head.

Berio: A-Ronne (1974)

CD: Luciano Berio: Many More Voices. BMG Classics/RCA Victor 09026-68302-2 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: Brazen Head

This 1998 treasure compiled three of Berio’s experimental vocal works: Thema (Omaggio a Joyce), Visage, and the original Dutch broadcast of A-Ronne. It’s been sadly out of print, and unavailable on digital media.

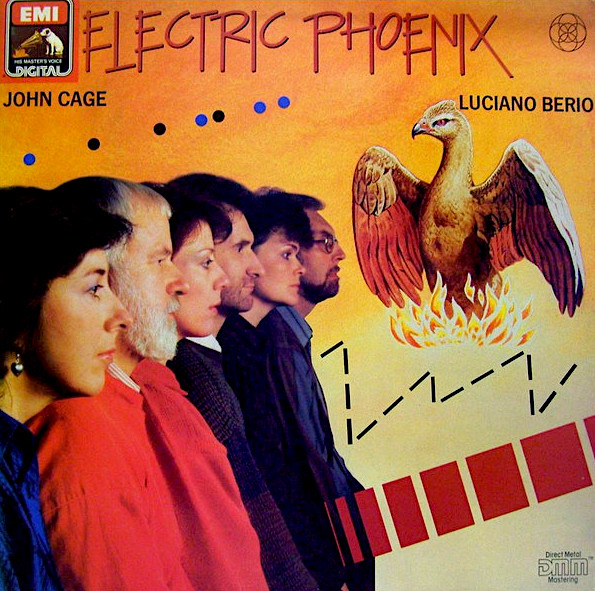

Berio: A-Ronne (1986)

Ensemble: Electric Phoenix

LP: Electric Phoenix: John Cage/Luciano Berio. His Master’s Voice 27 0452 1 (1986)

Online: Electric Phoenix Audio

In 1979 a few of the singers from Swingle II founded Electric Phoenix, a vocal group dedicated to electronically-oriented modern music. (As if this wasn’t evident from the glorious cover!) In 1986 Electric Phoenix released an LP featuring Berio’s A-Ronne, joined by William Billings’ Heath, Old North and John Cage’s Hymns and Variations. Strangely, this album has never made the transition to digital. How can that be? LOOK AT THE COVER!

Berio: A-Ronne (2005)

Ensemble: Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart

CD: Canticum novissimi testamenti & A-Ronne. Wergo WER66782 (2005)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

Here A-Ronne is sensibly paired with the last Berio piece to use a Sanguineti text, the stirring Canticum novissimi testamenti.

Berio: A-Ronne (2011)

Conductor: Paul Hillier

Ensemble: Theatre of Voices

SACD: Stories. Harmonia Mundi HMU807527 (2011)

Purchase: SACD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

This is multi-channel SACD features several modern compositions that rely on speaking, including John Cage’s Story and Cathy Berberian’s Stripsody. The sound quality is excellent—crystal-clear, especially if you have a 5.1 system and appropriate player—but one has to ask, “Why not record the A-Ronne for 8 singers?” Considering there’s only one recording of the 1975 version out there, this feels like a wasted opportunity. I mean—this is Paul Hillier’s Theatre of Voices, for god’s sake! Sing, sing the damn thing!

II. Version for Eight Voices (1975)

In 1975 Berio recomposed A-Ronne for eight singers. Dedicated to Ward Swingle and the Swingle II Singers, it premièred in Liège in 1975.

|

|

Berio: A-Ronne (1976)

Ensemble: Swingle II Singers

LP: A-Ronne & Cries of London. Decca HEAD 15 (1976)

CD: Berio: A-Ronne & Cries of London. Decca 425 620-2 (1990)

Purchase: CD [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

On 15 February 1976, Berio directed a recording of A-Ronne with the Swingle II Singers at Decca Studio 3 in West Hampstead. Ward Swingle’s second incarnation of his famous octet, the Swingle Singers had previously worked with Berio on Sinfonia. The LP was released later that year as HEAD 15: Berio: A-Ronne/Cries of London, notable for boasting one of the most badass covers in classical music history. Thank you, 1976! This recording went through several pressings, and was finally released on CD in 1990 as Decca 425 620-2. At this point, some idiot decided “Who wants to see a bearded, badass composer wreathed in cigar smoke when you can have random type blocks?” And yes, random—don’t be fooled by the “R, “E,” and “O.” What is that, an “S” and an “f”? What the fuck, Decca? Anyway, the most recent edition of this CD dates from 2010, but has since been deleted, and remains commercially unavailable as FLAC or MP3. Fortunately, you can hear the recording on YouTube!

Online Video

Documentary on A-Ronne

Unknown filmmaker and year

Posted by the cellist Richard Thomas on 6 December 2011, this is an excerpt from a British musical documentary that showcases Berio’s A-Ronne. The filmmakers clearly were fascinated by…mouths.

I. Version for Five Actors (1974)

A-Ronne

Actors: Unknown

Posted 31 March 2017, this performance seats the actors at a table, their environs shrouded in darkness. The video offers no additional details or credits.

A-Ronne

Actors: Cecilia López, Irma Sánchez, Maritza Nevárez, Diego Vega, & Sebastian Cobos

Recorded at the Teatro Carlos Lazo during the 2019 Festive Impulso in Mexico City, this kinetic performance was staged by Mario Espinosa Ricalde and Priscila Imaz. The actors do a terrific job, all the more impressive for having their lines memorized! Recommended.

A-Ronne

Actors: Agustina Lovecchio, Luciana Orellana, José Frau, Pedro Garabán, & Mauricio Lúquez

Recorded 10 October 2022 at the Espacio Contemporáneo de Arte in Mendoza, Argentina.

II. Version for Eight Singers (1975)

A-Ronne (Audio Ony: With Score)

Ensemble: Swingle II Singers; Conductor: Luciano Berio

This video uses the 1976 Swingle II recording to unscroll the score of A-Ronne. Absolutely fascinating!

A-Ronne

Ensemble: L’HommeArmé; Conductor: Fabio Lombardo

Recorded on 28 May 2013 at the Festival del Maggio Musicale in Florence, this performance was in cooperation with the Centro Tempo Reale, the musical institute Berio founded in 1987. As one might expect, it’s a flawless performance, impeccably staged following Berio’s directions—the singers stand at podiums arranged in an arc on stage.

A-Ronne (Excerpts)

Ensemble: Dan.Kias

Posted on 12 April 2018, this 6-minute trailer shows clips from a production of A-Ronne staged by the contemporary dance company Dans.Kias of Vienna. The eight singers are dressed in bathrobes and seated at a surreal table, all the while a trio of provocatively-dressed dancers attempts to distract them. The performance is excellent—it would be lovely to see the whole production posted!—but it’s very European, including a cross-dressing ballerina, a spider-legged temptress, and a woman in red lingerie.

A-Ronne (“A Day in the Library”)

Ensemble: The Norwegian Soloists’ Choir; Conductor: Grete Pedersen

Posted on 5 October 2021. This is an amazing performance of A-Ronne by the Norwegian Soloist’s Choir. Taking advantage of lockdown conditions, they film the performance in a library, making use of all available materials to convey Berio’s “characters.” Of all the versions of A-Ronne available on YouTube, this is the best one. While they lack the perfection of the Swingle II Singers—they don’t quite pull off the “reconstitutions,” for instance—they more than compensate with sheer invention, wittiness, and good cheer. It’s evident everyone involve really loves this piece, and they’re clearly having a blast. Highly recommended!

A-Ronne (Excerpt)

Ensemble: Ensemble Vokalzirkel; Conductor: Yuval Weinberg

Posted on 2 January 2024. Recorded live at the Hubertus Hall in Munich’s Nymphenburg Palace on 22 October 2022. With excellent video and audio, it’s a shame only the first five minutes of the performance have been uploaded! Nevertheless, for those who prefer conservatively-dressed Germans standing at podiums with little of the usual Eurotrash trappings that accompany such avant-garde performances, this recording offers a glimpse into what was certainly an enjoyable evening.

Additional Information

Photos from the 1974 Hilversum Production

The Centro Studi Luciano Berio site has some nice photographs from the Hilversum production. (All of which I borrowed for this page.)

The “Theatre of the Ear”: Analyzing Berio’s Musical Documentary A-Ronne

Nina Horvath, Musicological Explorations, Vol. 10, 2009. Horvath offers an insightful analysis of A-Ronne.

Multiple Layers of Meaning(s) in Luciano Berio’s A-Ronne

Martin Feuillerac, Dzielo musyczne znak, 2012. Another good discussion of Sanguineti’s allusions and Berio’s scoring.

Paywall:

Voicing the Labyrinth: the Collaborations of Edoardo Sanguineti and Luciano Berio

David Osmond-Smith, Twentieth-Century Music, 2012, 9(1-2), pp. 63-78. A deep dive into the Berio/Sanguineti partnership from Berio’s principal biographer.

Luciano Berio: Other Joyce-Related Works

Luciano Berio Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Luciano Berio profile.

Chamber Music (1953)

Three songs adapted from Joyce’s poetry.

Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) (1958)

An electronic transformation of the opening text from the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses read by Cathy Berberian.

Epifanie (1961/65)

A variable sequence of orchestral and vocal pieces, including texts from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.

Traces (1964)

Only given one performance and withdrawn, this “ghost opera” about racism was partially inspired by the “Circe” episode of Ulysses.

Sinfonia (1968/69)

This tour de force of music, voice, and sound incorporates text from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable. While it has no overt Joycean references, Sinfonia is frequently compared to Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

Outis (1996)

Berio’s opera about the transformations of Odysseus includes material borrowed from Joyce’s Ulysses.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 17 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com