Joyce Music – Barber: Nuvoletta

- At March 06, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I’m not unlearned in Joyce; I’ve read quite a few books on him. But what can you do when you get lines like “Nuvoletta reflected for the last time on her little long life, and she made up all her myriads of drifting minds in one. She cancelled all her engauzements. She climbed over the bannistars; she gave a chilly, childly, cloudy cry,” except to set them instinctively, as abstract music, almost as a vocalise?

—Samuel Barber, Interview with Philip Ramey, 1978

Nuvoletta

(1947)

Allegretto, op. 25; From Finnegans Wake

Composed shortly after the War, Nuvoletta is a delightful song adapted from the “Mookse and Gripes” fable in Finnegans Wake. In the Wake, Nuvoletta—rendered by Joseph Campbell as “Little Cloud Girl”—is one of the many forms taken by Izzy/Iseult. After failing to distract Mookse and Gripes from their zero-sum theological debate, she dissolves in tears, returning her essence to the great maternal river. Barber brings the story even more down-to-earth by reimagining Nuvoletta as a fickle young girl, her friends “asleeping with the squirrels.” Posturing as a parade of princesses, she fruitlessly attempts to attract attention to herself, presumably from indifferent adults. She finally flings herself from the “bannistar” in mock desperation.

One of Barber’s most complex songs, the music follows Joyce’s colorful language in lilting 3/8 time, as fickle and fluid as Nuvoletta herself. The song skips and pirouettes, comes to sudden stops, falls into a mock-reverential hush, and breaks free with colorful bursts of melismatic soprano. Barber called Nuvoletta “slightly ironic,” peppering the score with surprising delights, including a subdued “Tristan chord” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, snippets of atonality, and a playful reference to the “drowning theme” from Schubert’s “Der Müller und der Bach.”

Excerpt from Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music

By Barbara Heyman

Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music

Oxford University Press, 1992

Joyce’s prose was to inspire … Nuvoletta, which was finished 17 October 1947 while Barber was working with Eleanor Steber in preparation for the premiere of Knoxville: Summer of 1915. For Nuvoletta Barber drew excerpts from one of the most moving passages in Finnegans Wake, where the daughter (Nuvoletta-Isabel-Issy) plays one of her several death scenes. Her reflections are in typically multilayered Joycean language: invented words, double entendres, and puns that fuse conscious and unconscious meanings. The song was viewed as “for sophisticates only” by a British music critic, and even Barber confessed that he did not entirely understand the text:

What can you do when you get lines like “Nuvoletta reflected for the last time on her little long life, and she made up all her myriads of drifting minds in one. She cancelled all her engauzements. She climbed over the bannistars; she gave a chilly, childly, cloudy cry,” except to set them instinctively, as abstract music, almost as a vocalise?

Nevertheless, Joyce’s colorful prose prompted a kaleidoscope of musical imagery and puns: a monotonal plainsong incants From Vallee Maraia to Grasyaplaina, dormimust, echo!; a “Tristan chord” supports as were she born to bride with Tristis—Tristior; metric groupings correspond to the tears of night began to fall, first by ones and twos, then by threes and fours, at last by fives and sixes of sevens. The song, one of Barber’s longest and most capricious in mood, has a wide-range tessitura of two octaves (b# to b#”). Its rondolike form is interrupted with an elaborate vocal cadenza.

Steber sang the first performance of Nuvoletta, although the date is undocumented. In 1963 she recorded the song on a historic program of American songs sponsored by the Alice M. Ditson Fund and Columbia University. The recording … was called “treasurable” by Alan Rich, who cited Barber’s song for its wit and high art. Nuvoletta has been seldom performed, probably because the song demands from the singer a certain kind of endurance—that is, continued attention to exactly what mood is being projected—and a sustained balance between dramatic wit and gentle lyricism. Roberta Alexander’s recent recording is a welcome interpretation of this enigmatic song.

Excerpt from from “Singing Finnegans Wake: A Key to Samuel Barber’s Nuvoletta”

By Howard Pollack

Singing Finnegans Wake: A Key to Samuel Barber’s “Nuvoletta”

Journal of Singing, January/February 2022, Volume 78, No. 3, pp. 319–325

The song unfolds an ABA design that corresponds to these three primary sections, with dots indicating ellipses, and instrumental interludes essentially substituting for the omitted paragraphs. The opening A section, for Nuvoletta’s primping and posing, takes the shape of a fast and light waltz in 3/8, “Allegretto” and “con grazia,” rather French in style, and cast in a pandiatonic E major. The chantlike setting of Joyce’s parody of the Latin prayer Ave Maria leads to an F minorish middle section, “Adagio,” in which darkness falls amid tears and raindrops. A vocal cadenza at “O! O! O! Par la pluie!” serves as a transition back to E major and Nuvoletta’s descent into the river.

The piano part, which periodically reiterates the main four-note motive accompanying the first mention of Nuvoletta’s name, engages in some tone painting, as in the quotation of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde at the words, “Tristis Tristior Tristissimus”; the chiming repetition that follows “echo”; the irregular rhythms in the piano that match the numbers in the phrase, “by three and fours, at last by fives and sixes of sevens”; the cascading figure at “over the bannistars”; and the quivering gesture following “[a] lightdress fluttered.” As a whole, the song offers a fairly wide range of expression—from the coquettish to the mock tragic to the bittersweet—making this dramatic scena that much more effective in concert than on recording.

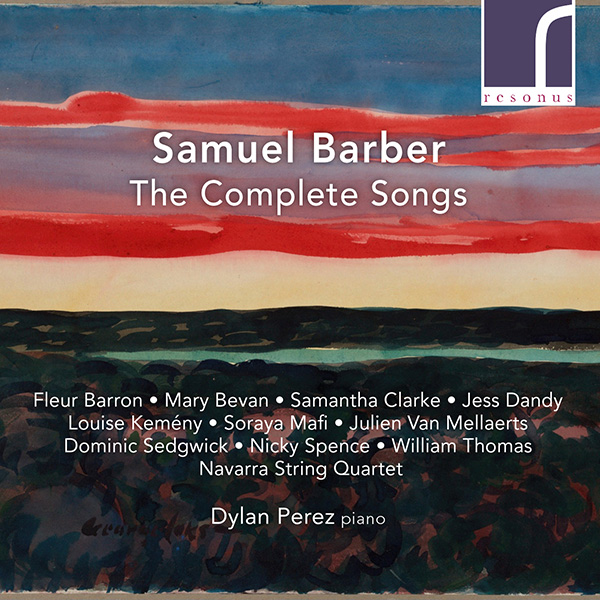

Liner Notes from Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs

By Dylan Perez

Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs

Resonus, 2022

Born in 1910, Samuel Barber knew what he wanted from very early in his life. Such strength of character and courage to follow his path is heard in his music; at a time when American classical music was heavily influenced by experimentalism, Barber’s inclination for ‘traditional’ harmony and melody helped set him apart. What I have always loved about Barber’s vocal music is the ease he finds in the marriage of text and music. Even in the posthumous songs, some recorded here for the first time, he always puts the text first, inspired by both contemporary and ancient texts.

In Nuvoletta, Op. 25, Barber returns to James Joyce, this time excerpting from Finnegans Wake. While the text is extremely dense, the excerpt that Barber chooses is a short scena that can be more easily understood, even if it is out of context. A little girl, Nuvoletta, is trying to catch the attention of others, only to fail and, in dramatic fashion, feigns suicide by jumping from a bannister. Barber’s ingenious setting marries Nuvoletta’s innocence with a lilting 3/8, the piano lightly commenting on the Joycean invented words that populate the text: sisteen shimmers, bannistar, sfumastelliacinous. Charming compositional techniques are found throughout, but hidden from the immediate ear of the listener; at mention of ‘Tristis Tristior Tristissimus’, a hint of Wagner’s Tristan shines through, while later when Nuvoletta’s tears fall in numbers, Barber mirrors them with intervallic leaps in the voice and rhythmic gestures in the piano. A melismatic weep brings the voice to the stratosphere before returning to the lilt found at the beginning, before Nuvoletta jumps and the song ends in a haze.

Texts

Nuvoletta

Nuvoletta in her lightdress,

spunn of sisteen shimmers,

was looking down on them,

leaning over the bannistars

and listening all she childishly could…

She was alone.

All her nubied companions

were asleeping with the squir’ls*…

She tried all the winsome wonsome ways

he four winds had taught her.

She tossed her sfumastelliacinous hair

like la princesse de la Petite Bretagne

and she rounded her mignons arms

like Mrs. Cornwallis-West

and she smiled over herself

like the image of a pose of a daughter

of the Emerour of Irelande

and she sighed after herself

as were she born to bride with Tristus

Tristior Tristissimus.

But, sweet madonine, she might fair as well

have carried her daisy’s worth to Florida…

Oh, how it was duusk!

From Vallee Maraia to Grasyaplainia,

dormimust echo!

A dew! Ah dew! It was so duusk

that the tears of night began to fall,

first by ones and twos,

then by threes and fours,

at last by fives and sixes of sevens,

for the tired ones were wecking,

as we weep now with them.

O! O! O! Par la pluie!…

Then Nuvoletta reflected for the last time

in her little long life

And she made up all her myriads

of drifting minds in one.

She cancelled all her engauzements.

She climbed over the bannistars;

she gave a childy cloudy cry:

Nuée! Nuée!

A lightdress fluttered

She was gone.

Finnegans Wake

The origin of the song is a long passage from Finnegans Wake, 157.8 to 159.20:

FW 157

Nuvoletta in her lightdress, spunn of sisteen shimmers, was

looking down on them, leaning over the bannistars and listening

all she childishly could. How she was brightened when Should-

rups in his glaubering hochskied his welkinstuck and how she

was overclused when Kneesknobs on his zwivvel was makeact-

ing such a paulse of himshelp! She was alone. All her nubied

companions were asleeping with the squirrels*. Their mivver,

Mrs Moonan, was off in the Fuerst quarter scrubbing the back-

steps of Number 28. Fuvver, that Skand, he was up in Norwood’s

sokaparlour, eating oceans of Voking’s Blemish. Nuvoletta lis-

tened as she reflected herself, though the heavenly one with his

constellatria and his emanations stood between, and she tried all

she tried to make the Mookse look up at her (but he was fore too

adiaptotously farseeing) and to make the Gripes hear how coy

she could be (though he was much too schystimatically auricular

about his ens to heed her) but it was all mild’s vapour moist. Not

even her feignt reflection, Nuvoluccia, could they toke their

gnoses off for their minds with intrepifide fate and bungless

curiasity, were conclaved with Heliogobbleus and Commodus

and Enobarbarus and whatever the coordinal dickens they did

as their damprauch of papyrs and buchstubs said. As if that was

their spiration! As if theirs could duiparate her queendim! As if

she would be third perty to search on search proceedings! She

tried all the winsome wonsome ways her four winds had taught

her. She tossed her sfumastelliacinous hair like le princesse de la

Petite Bretagne and she rounded her mignons arms like Mrs

Cornwallis-West and she smiled over herself like the beauty of

the image of the pose of the daughter of the queen of the Em-

perour of Irelande and she sighed after herself as were she born

FW 158

to bride with Tristis Tristior Tristissimus. But, sweet madonine,

she might fair as well have carried her daisy’s worth to Florida.

For the Mookse, a dogmad Accanite, were not amoosed and the

Gripes, a dubliboused Catalick, wis pinefully obliviscent.

—I see, she sighed. There are menner.

The siss of the whisp of the sigh of the softzing at the stir of

the ver grose O arundo of a long one in midias reeds: and shades

began to glidder along the banks, greepsing, greepsing, duusk

unto duusk, and it was as glooming as gloaming could be in the

waste of all peacable worlds. Metamnisia was allsoonome coloro-

form brune; citherior spiane an eaulande, innemorous and un-

numerose. The Mookse had a sound eyes right but he could not

all hear. The Gripes had light ears left yet he could but ill see.

He ceased. And he ceased, tung and trit, and it was neversoever

so dusk of both of them. But still Moo thought on the deeps of

the undths he would profoundth come the morrokse and still

Gri feeled of the scripes he would escipe if by grice he had luck

enoupes.

Oh, how it was duusk! From Vallee Maraia to Grasyaplaina,

dormimust echo! Ah dew! Ah dew! It was so duusk that the

tears of night began to fall, first by ones and twos, then by threes

and fours, at last by fives and sixes of sevens, for the tired ones

were wecking, as we weep now with them. O! O! O! Par la

pluie!

Then there came down to the thither bank a woman of no

appearance (I believe she was a Black with chills at her feet) and

she gathered up his hoariness the Mookse motamourfully where

he was spread and carried him away to her invisible dwelling,

thats hights, Aquila Rapax, for he was the holy sacred solem and

poshup spit of her boshop’s apron. So you see the Mookse he

had reason as I knew and you knew and he knew all along. And

there came down to the hither bank a woman to all important

(though they say that she was comely, spite the cold in her heed)

and, for he was as like it as blow it to a hawker’s hank, she

plucked down the Gripes, torn panicky autotone, in angeu from

his limb and cariad away its beotitubes with her to her unseen

FW 159

shieling, it is, De Rore Coeli. And so the poor Gripes got wrong;

for that is always how a Gripes is, always was and always will be.

And it was never so thoughtful of either of them. And there were

left now an only elmtree and but a stone. Polled with pietrous,

Sierre but saule. O! Yes! And Nuvoletta, a lass.

Then Nuvoletta reflected for the last time in her little long life

and she made up all her myriads of drifting minds in one. She

cancelled all her engauzements. She climbed over the bannistars;

she gave a childy cloudy cry: Nuée! Nuée! A lightdress fluttered.

She was gone. And into the river that had been a stream (for a

thousand of tears had gone eon her and come on her and she was

stout and struck on dancing and her muddied name was Missis-

liffi) there fell a tear, a singult tear, the loveliest of all tears (I

mean for those crylove fables fans who are ‘keen’ on the pretty-

pretty commonface sort of thing you meet by hopeharrods) for it

was a leaptear. But the river tripped on her by and by, lapping

as though her heart was brook: Why, why, why! Weh, O weh!

I’ve so silly to be flowing but I no canna stay!

No applause, please! Bast! The romescot nattleshaker will go

round your circulation in diu dursus.

*A Squirrelly Note

According to musicologist and Barber biographer Howard Pollack, Barber himself changed Joyce’s “squirrels” to “squir’ls,” apparently to “emphasize his wanting the word sung monosyllabically.” Finnegans Wake scholar David Hayman believes that Joyce’s “squirrels” may be a pun on “squires,” another reference to tie the Nuvoletta episode to the Tristan and Isolde legend. Interestingly, in Barber’s own 1953 performance with Leontyne Price, she pronounces the word normally as “squirrels,” as do most recorded singers except Gweneth-Ann Jeffers and Soraya Mafi, who both seem to be attempting a pun on “squeals.” (Maybe?) In any case, these off-beat pronunciations have the effect of elongating the word rather than shortening it. It’s a tough nut to crack!

Recordings

Complete Songs

There are three recordings of Samuel Barber’s complete songs available on compact disc.

|

|

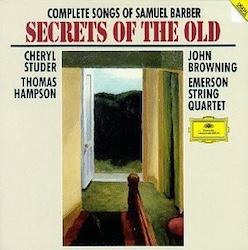

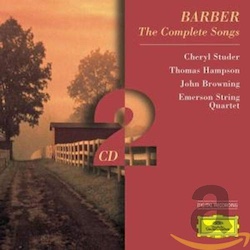

Barber: The Complete Songs (1994)

Piano: John Browning

Vocalists: Cheryl Studer, Thomas Hampson

CD: Complete Songs of Samuel Barber: Secrets of the Old. Deutsche Grammophon 435 867-2 (1994)

Reissue CD: Barber: The Complete Songs. Deutsche Grammophon 459 506-2 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Youtube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Recorded in 1991-1992 and released on Deutsche Grammophon in 1994, this venerable 2-CD set has never been out of print, a mandatory purchase for fans of Samuel Barber’s elegantly-crafted art songs. It features the soprano Cheryl Studer and the baritone Thomas Hampson, with John Browning on piano and the Emerson String Quartet backing Dover Beach. Having boasted several album covers and titles—including Secrets of the Old—this set continues to shine thirty years later. The liner notes are sparse and the production favors contemporary notions of close-miking and reverb, but the performances are stellar, all musicians in top form. John Browning was Barber’s own choice to première his Pulitzer-Prize winning Piano Concerto, so he’s as definitive a Barber interpreter as the twentieth century has to offer. Cheryl Studer is magnificent. While some operatic sopranos might be tempted to showy displays, Studer allows the lyrics to dictate her delivery, and she touches each word with an appropriate amount of grace, irony, impishness, and sorrow. (Her Nuvoletta is a delight!) And Thomas Hampson’s silky baritone is always a pleasure to hear. Although his voice is darker than the tenor Joyce had in mind, he brings a richness to each of his selections, especially the dramatic clangor of “I hear an army.” A collection that’s stood the test of time, Secrets of the Old—or whatever it’s being called at the moment!—belongs in the library of every classical music fan.

Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs (2022)

Piano: Dylan Perez

Vocalists: Fluer Barron, Jess Dandy, Louise Kemény, Soraya Mafi, Dominic Sedgwick, Nicky Spence, & others

CD: Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Resonus RES10301 (2022)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Since 1994, fans of Samuel Barber had only the Deutsche Grammophon Secrets of the Old set to represent Barber’s complete songs. As good as that set is, thirty years of the same interpretations can become overfamiliar! Fortunately, this 2-CD set by Resonus arrived in 2022 to freshen things up. Interested visitors are directed to the Brazen Head review of Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Here’s an excerpted passage describing the set’s Nuvoletta:

Of all the Joycean pieces, Nuvoletta is the most colorful, flecked with Wakean language, flickering rhythms, and soaring melisma. It’s also a song Cheryl Studer knocked out of the park; but Manchester soprano Soraya Mafi proves up to the challenge, her voice as nimble as Perez’s lilting piano. She leans into the Wakean puns through French and Latin, pronouncing “A dew! A dew!” as indistinguishable from “adieu” and chanting “From Vallee Maraia to Grasyaplainia, dormimust echo” with the perfect intonations of a mock “Hail Mary.” It’s a sunny, wistful delivery, quite in character with Nuvoletta herself.

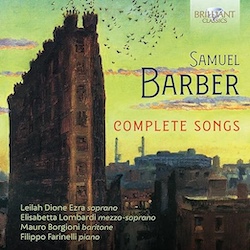

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs (2023)

Piano: Filippo Farinelli

Vocalists: Leilah Dione Ezra, Elisabetta Lombardi, Mauro Borgioni

CD: Brilliant Classics 96514 (2023)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Following close on the heels of the Resonus set is this wonderful release by Brilliant Classics, boasting no less than 65 of Barber’s songs—all the standard pieces from the famous Browning collection, plus many more early and lesser-known works. Interested visitors are directed to the Brazen Head review of Samuel Barber: Complete Songs. Here’s an excerpted passage describing the set’s Nuvoletta:

Farinelli takes the song at a slower tempo than usual—a full two minutes longer than Barber’s own performance with Leontyne Price, and one minute longer than most contemporary recordings. It’s a decision that pays off handsomely, giving him time to explore its many moods and complexities, allowing this “Little Cloud Girl” to make up “all her myriads of drifting minds in one.” The soprano Leilah Dione Ezra sings Nuvoletta with a consistent, honeyed tone that illuminates the song’s artful musicality, and it’s rarely sounded so beautiful—her “Tristus Tristior Tristissimus” is sublime. However, this commitment to beauty comes at the expense of the nimble wordplay of the lyrics. There’s a playful strangeness to this song that benefits from a more Protean approach, one that doesn’t gloss everything over with unrelenting “prettiness.”

Selected Songs

Nuvoletta is available on the following collections:

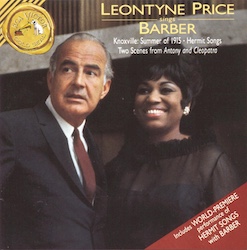

Barber: Nuvoletta (1953)

Piano: Samuel Barber

Soprano: Leontyne Price

CD: Leontyne Price Sings Barber. RCA Victor Gold Seal 09026-61983-2 (1994; recordings from 1953-1968)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

The great soprano Leontyne Price was Samuel Barber’s Cleopatra in his notoriously failed opera, Antony and Cleopatra. This CD collects Barber recordings she made in the 1950s and 1960s, and includes excerpts from the opera, as well as Nuvoletta and “Sleep now” from Three Songs op. 10. Like most of the tracks on this album, the two Joyce pieces were recorded live on 30 October 1953 during a recital at the Coolidge Auditorium in the Library of Congress, with Samuel Barber accompanying Price on piano. While the recording quality leaves much to be desired, Price’s amazing voice still soars above “Sleep now,” darting and hovering like an unquiet bird. Barber plays Nuvoletta at a significantly faster tempo than modern interpretations, whirling Price along until the song comes to a virtual standstill at “Oh, how it was duusk!” Obviously an essential addition to any Barber collection!

Barber: Nuvoletta (1988)

Piano: Tan Crone

Soprano: Roberta Alexander

CD: Barber: Songs. Etcetera KTC 1055 (1988)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Released in 1988 on Etcetera, this set features the soprano Roberta Alexander accompanied by pianist Tan Crone. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, the CD contains Three Songs op. 10, Nuvoletta, “Solitary Hotel,” and “In the dark pinewood.” Alexander also recorded a version of “I hear an army” with full orchestra.

Samuel Barber: Nuvoletta (1998)

Piano: Graham Johnson

Soprano: Ann Murray

CD: Irish Songs Bid Adieu. Forlane 16784 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Canadian soprano Morna Ann Murray shows off her classical chops by including Barber on this compilation of “Irish” songs—well, his lyricist was Irish, right? Along with such traditional classics as “Star of the County Down” and “The Roving Dingle Boy” we find Barber’s Three Songs op. 10. The result is exactly what one expects—very dramatic readings with plenty of vibrato, accompanied by a relentlessly dynamic piano. Drenched in sentimentality and showy theatrics, these renditions wouldn’t seem out of place in an Irish drawing room. Which means, Joyce probably would have loved them! Nuvoletta fares better than the Chamber Music pieces, and Murray is clearly having fun with the offbeat lyrics. Her “first by ones and twos, then by threes and fours” scampers along with delightful merriment, and she mercifully refrains from over-doing the “O! O! O! Par la pluie!” cadenza. For those more interested in the “song” part of Barber’s “art-songs,” Murray’s performance may be just the ticket.

Barber: Nuvoletta (2012)

Piano: Stephen de Pledge

Soprano: Gweneth-Ann Jeffers

CD: Mélodies Passagères: The Songs of Samuel Barber. Quartz QTZ2079 (2012)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Featuring British soprano Gweneth-Ann Jeffers and Kiwi pianist Stephen de Pledge, this collection takes its name from Barber’s suite of Rilke settings. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, the album contains Three Songs op. 10, Nuvoletta, and “Solitary Hotel.”

It’s the opus 10 Chamber Music songs that command the most attention here. Traditionally sung by a baritone, these songs are illuminated quite differently by Jeffers’ soprano, a tone frequently noted for its brightness and vibrato. “Rain has fallen” floats like an ethereal dream, gently buoyed by de Pledge’s responsive piano. “Sleep now” begins much the same, but its “unquiet” turn feels particularly sharp and anxious, shot through with spiky notes before slowly fading back into a dream. As usual, “I hear an army” is the main event, pushed into the stratosphere by Jeffers’ operatic soprano. As often happens when a familiar song is sung by someone of the opposite gender, it takes on unexpected nuances and new shades of meaning—think of the liberation of Patti Smith’s “Gloria,” or the desperation of Jack White’s “Jolene.” Here Joyce’s charging army seems less a manifestation of the singer’s unleashed emotions than a threat against her very safety, a symbol of her betrayal that threatens to overwhelm her. This is especially noteworthy in the final stanza. “My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair” is quietly voiced from a place of complete brokenness; but as the repetitions of “my love” gather momentum, the song climaxes in an outburst of righteous anger: “why have you left me alone?” With most baritone singers, the emphasis falls on “alone,” but Jeffers makes it clear her concern is “why.”

Jeffers gives Nuvoletta an adroit reading that takes full advantage of her range, milking “O! O! O! Par la pluie!” for all its worth. Her phrasing takes cues from Leontyne Price’s original, but unfolds at the contemporary faster tempo. Fortunately Jeffers’ operatic stylings are not at the expense of Joyce’s wordplay, and she’s the first recorded singer to pronounce “squir’ls” as a pun on “squires.” (Or maybe “squeals?”)

Of all the Joyce-related songs on this recording, “Solitary Hotel” is the weakest. De Pledge is too forward in the mix, obscuring Jeffers’ hushed intonations and clashing against her soaring moments of alarm. The production is additionally hampered by too much echo; a problem with the piano throughout the set, but especially troublesome here. Nor does Jeffers bring anything particularly interesting to the song, playing it for melodrama rather than nuance. Many sopranos have recorded “Solitary Hotel” since the release of Mélodies Passagères, and most have showed more sensitivity to the delicacy of Barber’s setting and mood.

Although I would have preferred a dryer production and more evenly-balanced piano, Mélodies Passagères is an essential Barber recording, despite the occasional misstep.

Samuel Barber: Nuvoletta (2015)

Piano: Maiko Inoué

Soprano: Anne Cambier

CD: American Songs. Etcetera KTC1527 (2015)

Purchase: CD [Presto Music], Digital [Amazon]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

Half the pieces on Anne Cambier and Maiko Inoué’s American Songs are by Samuel Barber, including a lovely version of Nuvoletta that embraces the song’s playfulness, but still provides an ample showcase for Cambier’s expressive soprano. A very solid interpretation, and not a bad choice between “parlor song” and “art song.”

Samuel Barber: Nuvoletta (2015)

Piano: Konrad Richter

Soprano: Bonita Glenn

Digital Release: Samuel Barber: Hermit Songs, etc. SWR 10500 (2018)

Purchase: Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Nuvoletta]

This digital release by SWR includes a version of Nuvoletta sung by the late American soprano Bonita Glenn accompanied by German pianist Konrad Richter. To the best of my knowledge, this is the longest version of Nuvoletta on record, clocking in at 6:04. Glenn and Richter use the additional space to fully inhabit the song’s bizarre world. Where Barber himself careened Price along a whirling joyride, Richter and Glenn approach the song like a short monodrama with distinct movements. Glenn’s reading is idiosyncratic, but ultimately winning. At first, she seems to be drowning the song in trilling vibrato, but then she allows the tension to build—“first by ones and twos, then by threes and fours.” The climactic “O! O! O!” shatters the ceiling, her voice escaping like a liberated bird. Richter allows a mindful second of silence to pass before rebuilding the song note by note, finally coming to his own fluttering climax under Glenn’s triumphant “Nuée!”

Samuel Barber: Nuvoletta (2019)

Piano: Hilko Dumno

Soprano: Kateryna Kasper

CD: O wüßt ich doch den Weg züruck. Tyxart (2019)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

This German album is translated as, Ah! If I but Knew the Way Back, and carries the subtitle Songs of Children and Fairy Lands. The songs are divided into three groupings, with Nuvoletta ending the first section: “The last sentence of Samuel Barber’s incredibly colourful Nuvoletta, ‘She was gone’, brings childhood to an end on our album; anyone who has read James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, however, will remember that Nuvoletta is an eternal child: An incarnation of water, she is reborn over and over again.” Kasper’s performance of Nuvoletta is sharp but whimsical, as befits the theme of the collection. (Just a note: Presto Music claims the track is sing in German. Sadly, this is not true.)

Online Audio

The following recorded performances are available on YouTube.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: K. Bird, Piano: C. Howard

Posted 28 February 2010. There’s no other information available for this track, but K. Bird sure does like vibrato!

Scherzo (Rekomposition Barber Nuvoletta)

Luis Reichard & Samuel Barber

This fascinating electronic piece uses Nuvoletta as musical material. From the 2014 album, Noch:Schon—Musik an der Schwelle (“Still:Already—Music on the Threshold.”)

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Laura Henry, Piano: Ka Nyoung Yoo

A live performance posted 25 August 2013.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Ann Moss, Piano: Steven Bailey

Performed in recital at Edward M. Pickman Hall, Bard College, 15 October 2015.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Rachel Mills, Piano: Katalin Zsubrits

A live performance from 4 January 2019, recorded in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Imogen Baker, Piano: Daniel Silcock

A live performance from 19 January 2024.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Isabel Merat, Piano: Unknown

This performance was posted to YouTube on 5 May 2022.

Barber: Nuvoletta

Mezzo: Patricia Hammond, Piano: Matt Redman

Posted 3 October 2022, Patricia Hammond takes a request for Nuvoletta for “Living Room Requests.”

Barber: Nuvoletta

Soprano: Leela Subramaniam, Piano: Cathy Miller

Live at UCLA Ostin Recording Studio in December 2022.

Additional Information

Singing Finnegans Wake: A Key to Samuel Barber’s “Nuvoletta”

By Howard Pollack. Journal of Singing, January/February 2022. An excellent essay on Barber, Joyce, and Nuvoletta.

Samuel Barber: Other Joyce-Related Works

Samuel Barber Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Samuel Barber profile.

Songs from Chamber Music (1935-1937)

These six songs are settings of poems from Chamber Music.

“Solitary Hotel” (1969)

From Despite & Still, this song has lyrics adapted from Ulysses.

Fadograph of a Yestern Scene (1971)

A short instrumental inspired from a line in Finnegans Wake.

“Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” (1972)

This song is based on James Joyce’s translation of a German poem by Gottfried Keller. It’s about a man who is buried alive.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 27 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com