Joyce Music – Barber: Chamber Music Songs

- At April 22, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I hope you may set all of “Chamber Music” in time. This was indeed partly my idea in writing it. The book is in fact a suite of songs and if I were a musician I suppose I should have set them to music myself.

—James Joyce, Letter to Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer, 19 July 1909

Songs Based on Chamber Music

(1935-1937)

For voice and piano

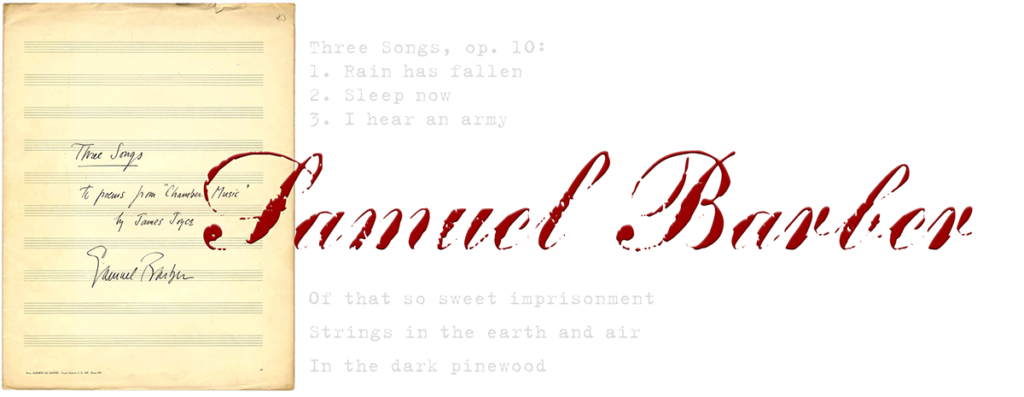

Three Songs, op. 10 (1935-1936)

1. Rain has fallen (Moderato; from Chamber Music XXXI)

2. Sleep now (Andante Tranquilo; from Chamber Music XXXIV)

3. I hear an army (Allegro con fuoco; from Chamber Music XXXVI)

“Of that so sweet imprisonment” (1935; Con moto; from Chamber Music XXII)

“Strings in the earth and air” (1935; Moderato; from Chamber Music I)

“In the dark pinewood” (1937; Moderato; from Chamber Music XX)

From their conception, James Joyce imagined the poems of Chamber Music as lyrics awaiting music, ready for a fine Irish tenor not unlike himself. Two months after they were printed, Dublin organist and composer Geoffrey Molyneux Palmer granted his wish, translating eight of the poems into songs. (Joyce enthusiastically urged Palmer to set the remaining 28 poems!) Belfast music critic W.B. Reynolds followed him a year later. Although neither published their work, Adolph Mann did, producing “Out By Donnycarney” in Cincinnati in 1910. Based on Poem XXXI, it was the first time James Joyce was published in America! Many more settings would follow, and today there are hundreds of songs drawn from Chamber Music.

Samuel Barber’s settings were made between 1935 and 1937. Scored for voice and piano, they were composed during Barber’s early period, concurrent with Adagio for Strings and Symphony In One Movement. The Library of Congress introduces these songs quite thoroughly:

In 1935, Samuel Barber was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, granting him a two-year period of study at the American Academy in Rome. While at the Academy, Barber composed several new songs, choosing poems from James Joyce’s Chamber Music as the texts for his settings. Of these songs composed, “Rain has fallen,” “Sleep now,” and “I hear an army,” were published collectively as Three Songs, op. 10, by G. Schirmer in 1939. The songs are related thematically, as each describes a love affair, as well as musically, with the first and last songs set in the key of C minor (A minor in the low voice edition), and the middle song residing a minor third lower. The first two songs were dedicated, respectively, to Barber’s friends Dario Cecchi and his sister Susanna, both of whom shared the composer’s appreciation of Joyce’s poetry.

Barber possessed an uncanny ability in choosing intelligent texts and was equally sensitive in setting the music to suit the poetry. He appreciated the rhythmic flow of the words and would often shift meters in his musical settings to accommodate the natural rhythm of the text. This is indeed the case in each of the songs in the op. 10 collection. Furthermore, each of the Three Songs also displays Barber’s penchant for embodying the meaning of the text in the piano accompaniment. For example, the accompaniment of the first song in the collection, “Rain has fallen,” is laden with arpeggios, undoubtedly intended to mimic the patter of rain. And in the finale of the collection, “I hear an army,” Barber uses an aggressive, galloping accompaniment to mirror Joyce’s poetic comparison of the approach of an army (and its thunderous horses) with that of the anger, bitterness, and betrayal experienced after the dissolution of a relationship.

The first two songs of the collection received their premiere in Rome at the Villa Aurelia at the American Academy on 22 April 1936, with Barber accompanying himself at the piano. The third song was heard nearly a year later, on 7 March 1937, at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia with mezzo-soprano Rose Bampton accompanied by the composer.

Of the myriad versions of Chamber Music, Samuel Barber’s settings are my favorites. Written while James Joyce was still alive, they’re unburdened by the reverence found in many latter Joyce-inspired works: there’s no sense of profound importance here, just discerning attention paid to the words themselves. A master of the “art song,” Barber is a better songwriter than Joyce was a poet, and his sophisticated settings give Joyce’s poems a vitality they sometimes lack on the page. Like sunlight on jewels, Barber’s music makes the verses sparkle and glow, revealing different facets and hidden depths. The ivory patter that opens “Rain has fallen,” the galloping that propels “I hear an army” towards its nightmare conclusion, the rising and falling arpeggios of “In the dark pinewood”—the piano remains sensitive to the lyrics, a nimble partner in a graceful dance between youthful innocence and bittersweet experience.

Excerpt from Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music

By Barbara Heyman

Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music

Oxford University Press, 1992

While at the academy, Barber also set to music four poems from James Joyce’s Chamber Music. The earliest, “Of that so sweet imprisonment,” was completed on 17 November 1935. “Rain has fallen,” “Sleep now,” and “Strings in the earth and air” were composed within a week of each other on 21 and 29 November and 5 December respectively. Two more Joyce poems were set later during a period of great happiness in St. Wolfgang, Austria—“I hear an army,” completed on 13 July 1936, and “In the dark pinewood” in 1937.

Of the six Joyce songs, “Rain has fallen,” “Sleep now,” and “I hear an army” were published by G. Schirmer in 1939 as Opus no. 10. Although it is not known on what basis Barber selected these three songs for publication, the choice seems logical since they form an interesting and unified cycle: they are tonally related—the first and last are in the same key (A minor for the low-voice edition, C minor for high voice), and the second song lies a minor third below; and the texts of the three songs provide a strong unity of theme and image—Barber mirrors the course of a love affair in settings that progress from lyrical to dramatic. “Rain has fallen” and “Sleep now” were dedicated respectively to Dario Cecchi and his sister Susanna, two Italian friends of Barber’s with whom he shared the pleasures of Joyce’s poetry. Suso Cecchi d’Amico said that at the time these songs were written James Joyce was their “discovery of the moment.” “We were all very young,” d’Amico recalled, “and we were very fond of Sam’s compositions. We didn’t discuss the poems together, they were a shared love.” For Barber, however, the reading was probably exploratory as well, for he always had in the back of his mind the feeling that he might come across a usable song text. His attraction to Joyce’s lyrics was undoubtedly determined more by the inherent lyricism and imagery of the poetry and its potential for translation into rhythmic and melodic language than by its popularity. Even though Barber’s songs were published before Joyce’s death in 1943, there is no evidence in either Joyce’s or Barber’s writings that the poet ever heard the songs.

Excerpt from Essay: “Opus Posthumous: James Joyce, Gottfried Keller, Othmar Schoeck, and Samuel Barber”

By Sebastian D.G. Knowles

Bronze by Gold: Joyce and Music

Garland Publishing, 1999

Barber wrote three other song settings of poems from Chamber Music during this period, which were published together as Op. 10 in 1939: “Rain Has Fallen,” “Sleep Now,” and “I Hear an Army” have now entered the literature as standard pieces for the rising young vocalist. These are more complex pieces, both to play and to sing, tracing a new adventurousness in Barber’s style. Where the three settings without opus numbers hold a single mood, reflective and undisturbed, the settings in Op. 10 each reach appassionato climaxes. The first climax, from “Rain Has Fallen,” anticipates two of Joyce’s siren songs, paralleling in its rhythm “Oh my Dolores” as trilled by Lydia Douce, the climax to “The Shade of the Palm,” and paralleling in its text the final “Come…! […] To me!” of “M’appari,” sung by Simon Dedalus. The climax of “Sleep Now,” in its text, takes us to “Sirens” again, via the aria “All is lost now” [Tutto è sciolto] from La Sonnambula. The third climax, from “I Hear an Army,” is, like the other two but more obviously so, a moment out of the piece’s natural rhythm, a lyrical elasticization of what is an otherwise forcefully rhythmic piece with a vibrant martial gallop; this is Barber’s nod to Schubert’s “Erlkönig,” where a different horse’s rhythm, also in the left hand, similarly stops for breath as the father discovers his dead son in his arms.

In the three published poems Barber takes the art song to a more visceral level: the hoofirons that ring steelily in “I Hear an Army” are the heartbeats of the abandoned lover. The poem was set to music in 1936 while Barber was in Austria, two years before Hitler’s incorporation of the country: the army is both a mobilizing war machine and an imaginary army of the heart. The heart, the last word of both “Rain Has Fallen” and “Sleep Now,” is Barber’s principal focus in Op. 10. The “unquiet heart” of “Sleep Now” continues the imagery of sleep found in “Of That So Sweet Imprisonment,” in which “Sleep to dreamier sleep be wed, / Where soul with soul lies prisoned.” And this imprisoned heart, beating in a perpetual sleep, may quop, as Blooms does in “Lestrygonians,” less softly when we remember “In the Dark Pinewood,” possibly the darkest of the six texts in its subject matter. There is an obvious pun on “wood” in “In the dark pinewood I would we lay,” which conceals a second pun on “pine.” The speaker pines to lie with his lover, yes, but pine is also the wood of choice when building a coffin. This further pun points obliquely to an issue that is central to all Joyce’s work, an issue Barber continues in his later, much more experimental, and much more disturbing settings of Joyce. When Joyce writes “In the dark pinewood I would we lay” he is writing about being buried alive.

Texts

Three Songs op. 10

1. Rain has fallen

Rain has fallen all the day.

O come along the laden trees:

The leaves lie thick upon the way

Of memories.

Staying a little by the way

Of memories shall we depart.

Come, my beloved, where I may

Speak to your heart.

2. Sleep now

Sleep now, O sleep now,

O you unquiet heart!

A voice crying “Sleep now”

Is heard in my heart.

The voice of the winter

Is heard in the door.

O sleep, for the winter

Is crying “Sleep no more.”

My kiss will give you peace now

And quiet to your heart—

Sleep on in peace now,

O you unquiet heart!

3. I hear an army

I hear an army charging upon the land,

And hear the thunder of horses plunging, foam about their

knees:

Arrogant, in black armour, behind them stand,

Disdaining the reins, with fluttering whips, the

charioteers.

They cry unto the night their battle name:

I moan in sleep when I hear afar their whirling

laughter.

They cleave the gloom of dreams, a blinding flame,

Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil.

They come shaking in triumph their long, green hair:

They come out of the sea and run shouting by the

shore.

My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair?

My love, my love, my love, why have you left me

alone?

Of that so sweet imprisonment

Of that so sweet imprisonment

My soul, dearest, is fain—

Soft arms that woo me to relent

And woo me to detain.

Ah, could they ever hold me there

Gladly were I prisoner!

Dearest, through interwoven arms

By love made tremulous,

That night allures me where alarms

Nowise may trouble us;

But sleep to dreamier sleep be wed

Where soul with soul lies prisoned.

Strings in the earth and air

Strings in the earth and air

Make music sweet;

Strings by the river where

The willows meet.

There’s music along the river

For Love wanders there,

Pale flowers on his mantle,

Dark leaves on his hair.

All softly playing,

With head to music bent,

And fingers straying

Upon an instrument.

In the dark pinewood

In the dark pinewood

I would we lay,

In deep cool shadows

At noon of day.

How sweet it is to lie there,

Sweet to kiss,

Where the great pine-forest

Enaisled is!

Thy kiss descending

Sweeter were

With the soft tumult

Of thy hair.

O, unto the pinewood

At noon of day

Come with me now,

Sweet love, away

Recordings

Complete Songs

There are three recordings of Samuel Barber’s complete songs available on compact disc.

|

|

Barber: The Complete Songs (1994)

Piano: John Browning

Vocalists: Cheryl Studer, Thomas Hampson

CD: Complete Songs of Samuel Barber: Secrets of the Old. Deutsche Grammophon 435 867-2 (1994)

Reissue CD: Barber: The Complete Songs. Deutsche Grammophon 459 506-2 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Youtube [Album Playlist]

Recorded in 1991-1992 and released on Deutsche Grammophon in 1994, this venerable 2-CD set has never been out of print, a mandatory purchase for fans of Samuel Barber’s elegantly-crafted art songs. It features the soprano Cheryl Studer and the baritone Thomas Hampson, with John Browning on piano and the Emerson String Quartet backing Dover Beach. Having boasted several album covers and titles—including Secrets of the Old—this set continues to shine thirty years later. The liner notes are sparse and the production favors contemporary notions of close-miking and reverb, but the performances are stellar, all musicians in top form. John Browning was Barber’s own choice to première his Pulitzer-Prize winning Piano Concerto, so he’s as definitive a Barber interpreter as the twentieth century has to offer. Cheryl Studer is magnificent. While some operatic sopranos might be tempted to showy displays, Studer allows the lyrics to dictate her delivery, and she touches each word with an appropriate amount of grace, irony, impishness, and sorrow. (Her Nuvoletta is a delight!) And Thomas Hampson’s silky baritone is always a pleasure to hear. Although his voice is darker than the tenor Joyce had in mind, he brings a richness to each of his selections, especially the dramatic clangor of “I hear an army.” A collection that’s stood the test of time, Secrets of the Old—or whatever it’s being called at the moment!—belongs in the library of every classical music fan.

Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs (2022)

Piano: Dylan Perez

Vocalists: Fluer Barron, Jess Dandy, Louise Kemény, Soraya Mafi, Dominic Sedgwick, Nicky Spence, & others

CD: Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Resonus RES10301 (2022)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Since 1994, fans of Samuel Barber had only the Deutsche Grammophon Secrets of the Old set to represent Barber’s complete songs. As good as that set is, thirty years of the same interpretations can become overfamiliar! Fortunately, this 2-CD set by Resonus arrived in 2022 to freshen things up. Interested visitors are directed to the Brazen Head review of Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Here’s an excerpted passage describing the set’s Chamber Music songs:

Here the [Three Songs] trio is sung by Scottish heldentenor and ENO favorite Nicky Spence. While his voice has more edge and bite than Thomas Hampson’s buttery-smooth baritone, he delivers a powerful and heartfelt performance. Lines like “Disdaining the reins with fluttering whips” and “Clanging, clanging upon the heart as upon an anvil” never sounded more desperate.

Soprano Louise Kemény sings the two most mellifluous selections from Chamber Music, “Of that so sweet imprisonment” and “Strings in the earth and air.” Both are delivered in high style, with yearning and quivering vibrato. Joyce’s invitation to a tryst, “In the dark pinewoods” is sung by the dynamic Fleur Barron, a protégé of the peerless Barbara Hannigan. Considering this song belongs to Hampson on the DG set, it’s a nice change, and Barron’s dusky mezzo is well-suited to these ambiguous verses of love and death. She shadows the piano deftly, stepping her voice across the lyrics and departing key words with graceful curlicues.

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs (2023)

Piano: Filippo Farinelli

Vocalists: Leilah Dione Ezra, Elisabetta Lombardi, Mauro Borgioni

CD: Brilliant Classics 96514 (2023)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Following close on the heels of the Resonus set is this wonderful release by Brilliant Classics, boasting no less than 65 of Barber’s songs—all the standard pieces from the famous Browning collection, plus many more early and lesser-known works. Interested visitors are directed to the Brazen Head review of Samuel Barber: Complete Songs. Here’s an excerpted passage describing the set’s Chamber Music songs:

All six songs from Chamber Music are sung by Mauro Borgioni, whose dark baritone enfolds Farinelli’s flashing piano like a warm, Italian night. These are dramatic readings that wouldn’t seem out of place at La Scala—“I hear an army” unfolds like thunder rumbling across a tortured landscape, and Borgioni’s “why have you left me alone?” raises goosebumps. (He’s also fond of rolling his r’s and cutting off stanzas with a theatrical slash—I would love to see him as Baron Scarpia!) While some might prefer a less ornate reading, Borgioni’s idiosyncratic pronunciation is a more pressing concern, and it’s clear English is not his native language. This is the most evident on “In the dark pinewood,” where words like “shadows,” “kiss,” “enaisled,” and “tumult” strike the ear with discernible accents. Still, it’s hard to hold that against him when he draws out the conclusion of “Stings in the earth and air” with such graceful delicacy.

Farinelli matches Borgioni’s theatricality with dramatic displays of his own, slowly building up and unwinding the tension in “Rain has fallen,” and drawing out the chords in “Sleep now” like the drifting thoughts and sudden anxieties of an unquiet night. And never have the galloping horses of “I hear an army” felt more ominous—just terrific playing, even on the simplistic ascending/descending riffs of “Pinewood.”

Selected Songs

There are dozens of recordings of Barber’s Chamber Music songs; too many to list here. The following selections represent historically important recordings, near-complete recordings, or personal favorites.

Barber: “Sleep now” (1953)

Piano: Samuel Barber

Soprano: Leontyne Price

CD: Leontyne Price Sings Barber. RCA Victor Gold Seal 09026-61983-2 (1994; recordings from 1953-1968)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Sleep now]

The great soprano Leontyne Price was Samuel Barber’s Cleopatra in his notoriously failed opera, Antony and Cleopatra. This CD collects Barber recordings she made in the 1950s and 1960s, and includes excerpts from the opera, as well as Nuvoletta and “Sleep now” from Three Songs op. 10. Like most of the tracks on this album, the two Joyce pieces were recorded live on 30 October 1953 during a recital at the Coolidge Auditorium in the Library of Congress, with Samuel Barber accompanying Price on piano. While the recording quality leaves much to be desired, Price’s amazing voice still soars above “Sleep now,” darting and hovering like an unquiet bird. Barber plays Nuvoletta at a significantly faster tempo than modern interpretations, whirling Price along until the song comes to a virtual standstill at “Oh, how it was duusk!” Obviously an essential addition to any Barber collection!

|

|

Barber: “Sleep now,” “I hear an army” (1982)

Piano: David Garvey

Mezzo: Glenda Maurice

LP: Britten/Barber. Etcetera ETC 1002 (1982)

CD: Samuel Barber/Benjamin Britten. Globe GLO 5017 (1989)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Oh it has a terrible cover. And Garvey’s piano never rises above the level of “solid accompanist.” But the late American singer Glenda Maurice has her following, and her bright mezzo-soprano is certainly expressive. These are dramatic readings; perhaps overcooked but never melting into gooey sentimentality. Maurice sings two songs from Three Songs op. 10, a flowery “Sleep Now” and a melodramatic “I hear an army.” While it doesn’t approach the intensity of Gweneth-Ann Jeffers’ recording thirty years later, Maurice’s final “Why have you left me alone” conveys genuine anguish. The album also features the entirety of Three Songs, op. 45. Maurice drenches “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” with despair, her final “Amen” a resigned passing unto death.

Barber: Three Songs op. 10; “In the dark pinewood” (1988)

Piano: Tan Crone

Soprano: Roberta Alexander

CD: Barber: Songs. Etcetera KTC 1055 (1988)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Released in 1988 on Etcetera, this set features the soprano Roberta Alexander accompanied by pianist Tan Crone. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, the CD contains Three Songs op. 10, Nuvoletta, “Solitary Hotel,” and “In the dark pinewood.” Alexander also recorded a version of “I hear an army” with full orchestra.

|

|

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 10 (1994)

Piano: Roger Vignoles

Baritone: Sir Thomas Allen

CD: Barber: Dover Beach. Virgin Classics 7243 5 45033 2 0 (1994)

Reissue CD: American Classics: Samuel Barber. EMI Classics 50999 6 95232 2 9 (2009)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

This collection was originally issued on CD by Virgin Classics Digital. It was reissued in 2009 by EMI with a different name, a new cover, and five additional tracks: the songs of Despite and Still, op. 41, with Eric Cutler singing tenor and Bradley Moore on piano. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, both versions contain Three Songs op. 10 and “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose,” but only the 2009 EMI release features “Solitary Hotel.” The Robert Vignoles/Thomas Allen songs were recorded at St. George’s Church in Bristol in April 1993. Allen has a strong, resonant baritone and Vignoles is a capable accompanist, but there’s nothing to recommend this disc over the superior DG set released that same year. There’s also a hollowness to the sound quality that one associates with budget releases. Despite and Still fares better than the earlier recordings, but it’s safe to give this collection a pass.

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 10 (1998)

Piano: Graham Johnson

Soprano: Ann Murray

CD: Irish Songs Bid Adieu. Forlane 16784 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Canadian soprano Morna Ann Murray shows off her classical chops by including Barber on this compilation of “Irish” songs—well, his lyricist was Irish, right? Along with such traditional classics as “Star of the County Down” and “The Roving Dingle Boy” we find Barber’s Three Songs op. 10. The result is exactly what one expects—very dramatic readings with plenty of vibrato, accompanied by a relentlessly dynamic piano. Drenched in sentimentality and showy theatrics, these renditions wouldn’t seem out of place in an Irish drawing room. Which means, Joyce probably would have loved them! Nuvoletta fares better than the Chamber Music pieces, and Murray is clearly having fun with the offbeat lyrics. Her “first by ones and twos, then by threes and fours” scampers along with delightful merriment, and she mercifully refrains from over-doing the “O! O! O! Par la pluie!” cadenza. For those more interested in the “song” part of Barber’s “art-songs,” Murray’s performance may be just the ticket.

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 10; “In the dark pinewood” (2007)

Piano: Julius Drake

Baritone: Gerald Finley

CD: Songs by Samuel Barber. Hyperion CDA67528 (2007)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

This set features the Canadian baritone Gerald Finley—“Doctor Atomic” himself—accompanied by his long-time musical partner, the English pianist Julius Drake. It contains Three Songs op. 10 and “In the dark pinewood.” Featuring a dry production with a broad soundstage, the songs have an immediacy many earlier recordings lack, and Finley’s flexible baritone is always a delight. Drake matches Finley’s changing moods and phrasings with elegant sensitivity, more a partner in a duet than a traditional accompanist. The Joycean highlight is “I hear an army,” an excellent showcase for the theatricality Finley honed portraying Don Giovanni and J. Robert Oppenheimer. Like all Finley/Drake collaborations, highly recommended.

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 10 (2012)

Piano: Stephen de Pledge

Soprano: Gweneth-Ann Jeffers

CD: Mélodies Passagères: The Songs of Samuel Barber. Quartz QTZ2079 (2012)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

Featuring British soprano Gweneth-Ann Jeffers and Kiwi pianist Stephen de Pledge, this collection takes its name from Barber’s suite of Rilke settings. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, the album contains Three Songs op. 10, Nuvoletta, and “Solitary Hotel.”

It’s the opus 10 Chamber Music songs that command the most attention here. Traditionally sung by a baritone, these songs are illuminated quite differently by Jeffers’ soprano, a tone frequently noted for its brightness and vibrato. “Rain has fallen” floats like an ethereal dream, gently buoyed by de Pledge’s responsive piano. “Sleep now” begins much the same, but its “unquiet” turn feels particularly sharp and anxious, shot through with spiky notes before slowly fading back into a dream. As usual, “I hear an army” is the main event, pushed into the stratosphere by Jeffers’ operatic soprano. As often happens when a familiar song is sung by someone of the opposite gender, it takes on unexpected nuances and new shades of meaning—think of the liberation of Patti Smith’s “Gloria,” or the desperation of Jack White’s “Jolene.” Here Joyce’s charging army seems less a manifestation of the singer’s unleashed emotions than a threat against her very safety, a symbol of her betrayal that threatens to overwhelm her. This is especially noteworthy in the final stanza. “My heart, have you no wisdom thus to despair” is quietly voiced from a place of complete brokenness; but as the repetitions of “my love” gather momentum, the song climaxes in an outburst of righteous anger: “why have you left me alone?” With most baritone singers, the emphasis falls on “alone,” but Jeffers makes it clear her concern is “why.”

Jeffers gives Nuvoletta an adroit reading that takes full advantage of her range, milking “O! O! O! Par la pluie!” for all its worth. Her phrasing takes cues from Leontyne Price’s original, but unfolds at the contemporary faster tempo. Fortunately Jeffers’ operatic stylings are not at the expense of Joyce’s wordplay, and she’s the first recorded singer to pronounce “squir’ls” as a pun on “squires.” (Or maybe “squeals?”)

Of all the Joyce-related songs on this recording, “Solitary Hotel” is the weakest. De Pledge is too forward in the mix, obscuring Jeffers’ hushed intonations and clashing against her soaring moments of alarm. The production is additionally hampered by too much echo; a problem with the piano throughout the set, but especially troublesome here. Nor does Jeffers bring anything particularly interesting to the song, playing it for melodrama rather than nuance. Many sopranos have recorded “Solitary Hotel” since the release of Mélodies Passagères, and most have showed more sensitivity to the delicacy of Barber’s setting and mood.

Although I would have preferred a dryer production and more evenly-balanced piano, Mélodies Passagères is an essential Barber recording, despite the occasional misstep.

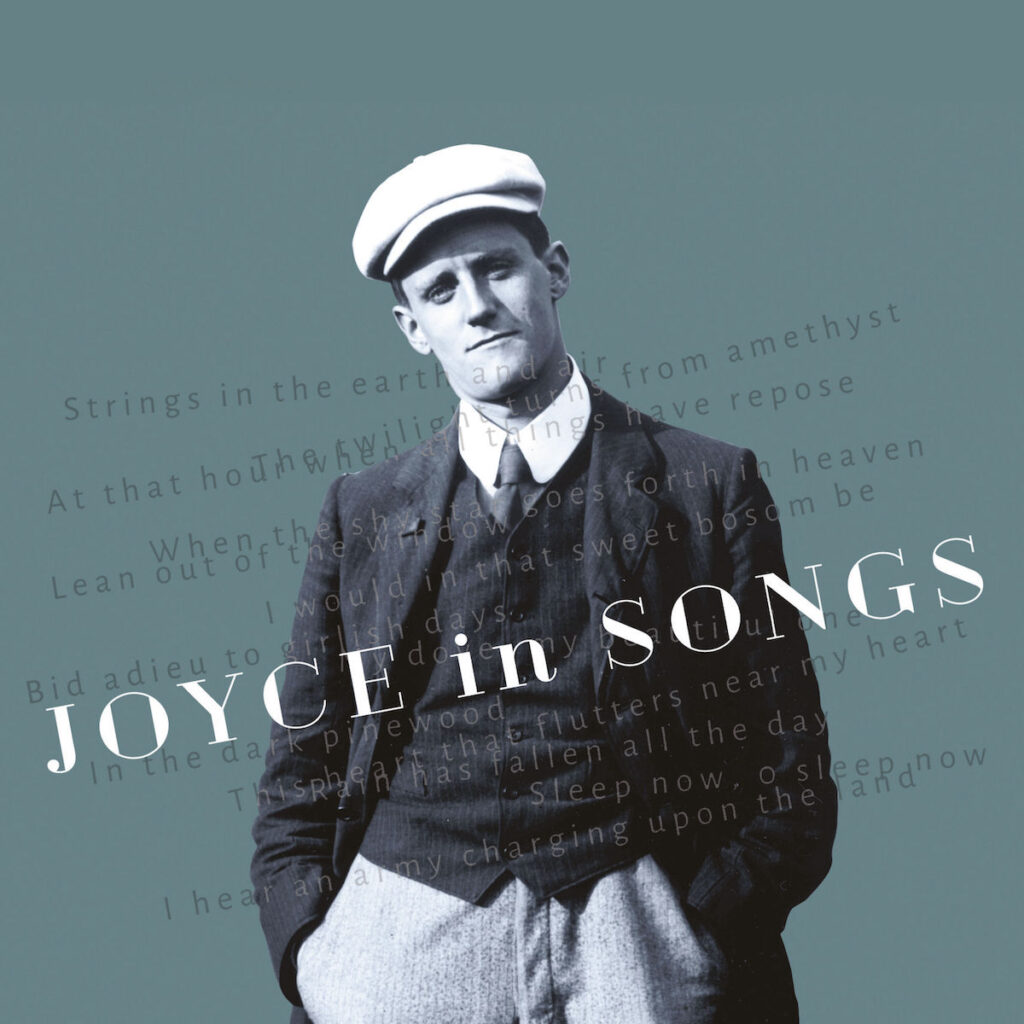

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 10 (2024)

Piano: Stanisław Bromboszcz

Baritone: Maciej Bartczak

CD: Joyce In Songs. CD Accord ACD310 (2024)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist]

This Polish album showcases songs inspired by the poetry of James Joyce. It includes Samuel Barber’s Three Songs, op. 10 and “Solitary Hotel,”

Józef Świder’s Chamber Music suite, three Chamber Music songs from Ben Moore, and two world premieres: Wojciech Stępień Wind Whines, a setting of three poems from Pomes Penyeach; and Marta Kleszcz’s Two Songs, settings of Chamber Music Poem XI and Poem XIV. The set concludes with Joyce’s friend Edmund J. Pendleton’s “Bid Adieu,” with lyrics adapted from Poem XI. All the pieces are sung by Polish baritone Maciej Bartczak, who is accompanied on piano by Stanisław Bromboszcz.

Bartczak has a lovely baritone; a bit fuzzy at the edges, but possessing a wide emotional range. His “Rain has fallen” is among the saddest versions I’ve heard, while “Sleep now” is cradled in a gentle hush. He’s unable to shake a Polish accent that occasionally distorts the English lyrics, but his sincerity carries the listener through these melancholy landscapes. Not so with “I hear an army.” The song’s galloping pace and frantic lyrics expose Bartczak’s linguistic limitations, and his delivery is comically bad. While one can overlook—or even appreciate—a mild accent, Bartczak hammers the lyrics over an Eastern European anvil until prose and meter are bent hopelessly out of shape: “I hear an army charting up of th’lend, and the T’UNder of horsezzPLANging, foam-and-all-their knees, erro-GENT inbleck armer, be’hinthem stend…” It’s that bad. Additionally, he makes some inexplicable decisions in phrasing that swallow up key words.

Fortunately Bartczak’s accent is less distracting on “Solitary Hotel.” He approaches the song like a storyteller, unfolding the narrative with a theatrical intensity over Bromboszcz’s pensive piano.

All in all, this recording is most valuable as a showcase for lesser-known Polish composers such as Józef Świder, Wojciech Stępień, and Marta Kleszcz. If you’re mostly interested in the Barber songs, much better options are available. (To be fair, the same can be said about Ben Moore’s songs, three of which were covered by Deborah Voigt on All My Heart.)

Online Video

There are dozens of performances of Barber’s Chamber Music songs available on YouTube. The following is just a sample:

Barber: “Sleep now”

Soprano: Esther Hinds, Piano: Samuel Barber

A live performance from 1977 featuring Barber himself on piano.

Barber: Three Songs, op. 10

Baritone: Maurice Lenhard, Piano: Noritaka Tsutsui

A live performance from 23 July 2015, recorded at the Hochschule für Musik Trossingen.

Barber: “I hear an army”

Baritone: Simon Barrad, Piano: Joel Papinoja

A live performance from 18 January 2017, recorded at the Helsinki Music Centre.

Barber: Three Songs, op. 10

Baritone: Mauro Borgioni, Piano: Filippo Farinelli

A live performance from 17 September 2018, recorded at San Filippo Neri’s Church in Perugia during the “Sagra Musicale Umbra” festival. Farinelli and Borgioni would later go on to record a complete set of Barber songs for Brilliant Classics.

Additional Information

Samuel Barber Wikipedia Page

The Wikipedia entry on Samuel Barber borrows much of its material from Barber Heyman’s biography.

Library of Congress Samuel Barber Collection

The Library of Congress holds several of Barber’s works available for viewing as PDFs, including the original scores to “Rain has fallen,” “Solitary Hotel,” and “I hear an army.”

Samuel Barber: Other Joyce-Related Works

Samuel Barber Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Samuel Barber profile.

Nuvoletta (1947)

A playful song with lyrics adapted from Finnegans Wake.

“Solitary Hotel” (1969)

From Despite & Still, this song has lyrics adapted from Ulysses.

Fadograph of a Yestern Scene (1971)

A short orchestra piece inspired by a line in Finnegans Wake.

“Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” (1972)

This song is based on James Joyce’s translation of a German poem by Gottfried Keller. It’s about a man who is buried alive.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 30 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com