Joyce Music: Samuel Barber

- At July 20, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

There’s no reason music should be difficult for an audience to understand.

—Samuel Barber

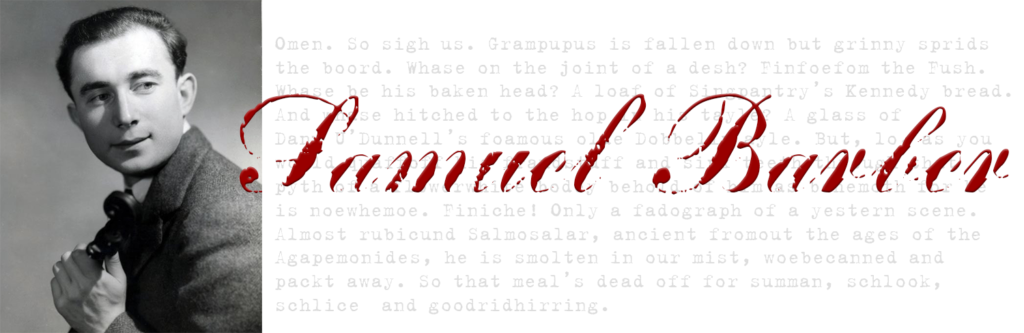

Samuel Barber

(1910-1981)

One of the great Romantics of twentieth-century music, Samuel Osmond Barber II was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania to musical parents who wanted their child to lead a more “normal” life. After composing his first piano piece at age 7, two years later Barber disabused them of that notion with an oft-quoted letter:

Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don’t cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell it now without any nonsense. To begin with I was not meant to be an athlet. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I’m sure. I’ll ask you one more thing.—Don’t ask me to try to forget this unpleasant thing and go play football.—Please—Sometimes I’ve been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad (not very).

Putting aside the dreaded football, Barber wrote his first operetta a year later, and became a professional organist at Westminster Church at age 12. He graduated from the Curtis Musical Institute in Philadelphia in 1934 and continued to study music in Vienna and Rome.

Barber established a name for himself with pieces like Symphony in One Movement and Adagio for Strings, still his most famous composition. After serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II, Barber and his partner, the Italian-American opera composer Gian Carlo Menotti, purchased a sprawling woodland home they named “Capricorn.” Dividing their time between New York City, Mount Kisco, and Europe, the pair lived a Bohemian lifestyle, surrounding themselves with poets, musicians, travelers, and artists. In 1958 Barber won the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his opera Vanessa, which featured a libretto written by Menotti. He won the Pulitzer again in 1962 for his Piano Concerto, commissioned to celebrate the opening of Lincoln Center and premièred by pianist John Browning. Samuel Barber was at the peak of his career.

A musical adventurer, Barber explored a wide range of compositional techniques. Classical structures, late-Romantic chromaticism, the lyricism of Italian opera, twentieth-century dissonance and atonality, jazz, art songs, Tin Pan Alley, Broadway—all were fair game for Barber, alchemized by his genius into something uniquely his own and seamlessly integrated into the Barber sound. A perfectionist, Barber was also a tinkerer, frequently revising his works or creating new works from old. While some contemporary critics and academics disparaged Barber for his unabashed embrace of tonality, audiences adored his works, and he was considered a quintessential American composer both at home and abroad.

Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti (1945)

Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti (1945)

In 1966 Barber composed his third opera, Antony and Cleopatra, based on the Shakespeare play and starring Leontyne Price as Cleopatra. Written to open the Metropolitan Opera House, no expense was spared on Franco Zeffirelli’s lavish production. Sadly, it was this gaudiness and excess—coupled with some ludicrous technical problems—that bombed the opera, and critics were savage in their reviews. Although Barber’s music was spared the worst of the criticism, his name was forever linked with the “hair-curlingly bad” production, a fiasco that served as a “landmark of vulgarity.”

This failure marked a turning point, and Barber fell into a depression. His relationship with Menotti also soured, as Gian Carlo made it perfectly clear his sexual needs included much younger men. The pair officially split in 1970, and Capricorn was placed on the market. Although Barber continued to compose, he spent much of his time in isolation, battling alcoholism and despair. Samuel Barber died of cancer in 1981, tragically believing his star had fallen.

While only the passage of time can reveal which artists are destined for greatness, it’s safe to say that Samuel Barber’s star is still shining brightly. While his operas aren’t staged as often as they deserve, his Adagio for Strings has gracefully entered the canon, and his art songs are constantly being re-discovered by performers and audiences hungry for sophistication and beauty. There’s a wit to Barber’s music, an élan more often associated with composers like Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, and George Gershwin than his classical contemporaries such as Aaron Copland, Walter Piston, or even his own partner, Gian Carlo Menotti. Barber’s music is beautiful, yes; and emotional, but it never resorts to gimmickry or cheap sentimentality.

Barber frequently turned to literature for inspiration, and the list of writers he’s set to music is impressive: James Agee, Matthew Arnold, W.H. Auden, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Henry Davies, Robert Graves, A.E. Housman, Langston Hughes, Rainer Maria Rilke, Theodore Roethke, William Shakespeare, Percy Bysshe Shelley, James Stephens, Algernon Swinburne, W.B. Yeats—just to name a few! But of all these, James Joyce was his favorite, inspiring nine wonderful songs and one instrumental.

Joyce-Related Works

Songs from Chamber Music (1935-1937)

These six songs are settings of poems from Chamber Music.

Nuvoletta (1947)

A playful song with lyrics adapted from Finnegans Wake.

“Solitary Hotel” (1969)

From Despite & Still, this song has lyrics adapted from Ulysses.

Fadograph of a Yestern Scene (1971)

A short orchestra piece inspired by a line in Finnegans Wake.

“Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” (1972)

This song is based on James Joyce’s translation of a German poem by Gottfried Keller. It’s about a man who is buried alive.

A Finnegans Wake Ballet?

According to James P. Sullivan writing in the James Joyce Quarterly, Samuel Barber was planning on scoring a ballet based on Finnegans Wake:

[Padraic Colum] even prepared the scenario for a ballet version of Finnegans Wake (with choreography by British expatriate Anthony Tudor, then of the American Ballet Theatre, and music by the American composer Samuel Barber, one of the most anticipated collaborations of the post-war period).

This proposed ballet is not mentioned in Heyman’s definitive biography of Samuel Barber, nor anywhere else I could locate on the Internet. If any visitor has any information about this Wakean project, please contact the Brazen Head!

The young people are not interested in writers. Mrs. Yeats lives on, forgotten, and Maud Gonne, the flashing beautiful one, is an old lady now, and it bores people when she is mentioned… The Abbey Theatre burned down, Joyce but a man who wrote dirty books… I walked through St. Stephen’s Green and the court at Trinity College and thought about all this, and how beautiful the first chapter of “Ulysses” is, and the Tower scene by the sea (so many towers—which one was it?) and was glad to hop on my little plane again and leave this strangely dead city.

—Samuel Barber, after a disappointing visit to Dublin in 1952

Additional Information

Additional Information

Samuel Barber Wikipedia Page

The Wikipedia entry on Samuel Barber borrows much of its material from Barber Heyman’s biography.

Library of Congress Samuel Barber Collection

The Library of Congress holds several of Barber’s works available for viewing as PDFs, including the original scores to “Rain has fallen,” “Solitary Hotel,” and “I hear an army.”

ClassicalNet Samuel Barber Page

A nice Barber biography is available on ClassicalNet.

Gay Influence: American Composer Samuel Barber

Terry’s “Gay Influence” blog features an informative post about Barber and Menotti.

Samuel Barber: Absolute Beauty

The Web page for H. Paul Moon’s 2017 documentary about Samuel Barber.

“A Cup of Tea, a Fireplace and the Cows”

Playbill, 2 November 2007. Mary Jane Phillips remembers Samuel Barber and Gian Carlo Menotti.

The Life and Music of Samuel Barber

5 March 2010, NPR. An appreciation of Samuel Barber by Ted Libbey.

Selected Books

Samuel Barber: The Composer and His Music

By Barbara B. Heyman

First Edition: Oxford University Press, 1992

Second Edition: Oxford University Press, 2020

Barbara Heyman’s definitive biography was instrumental in creating the Brazen Head’s Samuel Barber pages. Her research is cited and quoted almost everywhere people write about Barber, from the Samuel Barber Wikipedia page to the Knowles essay referenced below.

Bronze by Gold: The Music of Joyce

Edited by Sebastian D.G. Knowles

Garland Publishing, 1999

This collection of essays on the topic of Joyce and music features Sebastian D.G. Knowles’ “Opus Posthumous: James Joyce, Gottfried Keller, Othmar Schoek, and Samuel Barber.” It’s an extensively researched and surprisingly readable analysis of Barber’s Joyce settings, particularly “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose.”

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com