Joyce Biography: Family & Associates

- At May 28, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Joyce Biography: Family & Associates

This page profiles biographies of Joyce’s family, friends, and associates. The books are listed by publication date. Clicking a cover image takes you to Amazon.com. When Brazen Head commentary is unavailable, the publisher’s summaries are usually reprinted. If any knowledgeable Joyce reader would like to review, summarize, or provide additional information for any of these “uncommented” books, please drop us a line! Additional Joyce-related biographies may be found by clicking the links below:

Joyce Biography

[Main Page | Biographical Sketch | Chronology | Joyce Biographies | Family & Associates | Memoirs & Photos | Letters | Dublin]

Shakespeare and Company: The Story of an American Bookshop in Paris

Shakespeare and Company

By Sylvia Beach

Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1959

Available online at: Internet Archive

Publisher’s Description: Sylvia Beach was intimately acquainted with the expatriate and visiting writers of the Lost Generation, a label that she never accepted. Like moths of great promise, they were drawn to her well-lighted bookstore and warm hearth on the Left Bank. Shakespeare and Company evokes the zeitgeist of an era through its revealing glimpses of James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, Andre Gide, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, D. H. Lawrence, and others already famous or soon to be. In his introduction to this new edition, James Laughlin recalls his friendship with Sylvia Beach. Like her bookstore, his publishing house, New Directions, is considered a cultural touchstone.

Dear Miss Weaver: Harriet Shaw Weaver 1876-1961

Dear Miss Weaver: Harriet Shaw Weaver 1876-1961

By Jane Lidderdale & Mary Nicholson

Viking, 1971

Available online at: Internet Archive

Bob Williams: Dear Miss Weaver is an extraordinary book. Instead of a brief memorial of little skill, this is an accomplished performance and of a scale (455 pages) suitable to the importance of its subject. The relations between Miss Weaver and Mr Joyce deteriorated in the 30s. The authors detail this with an impartiality which is the more becoming in that one of the writers was Miss Weaver’s niece. There are some bizarre typographical aberrations but no major problems. There are many photographs, including one of Joyce—a formal portrait in profile—that I had never seen before. Certainly worth reading and, since I expect to refer to it often, worth owning too.

Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation

Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation

By Noel Riley Fitch

W.W. Norton & Co., 1985

Available online at: Internet Archive

Tim Miller: Fitch’s book is a gem from start to finish, a definitive guide to the inter-War Paris literary scene as well as Beach’s relationship, as publisher and friend, to James Joyce. The narrative naturally revolves around the hub of literary life in Paris, Beach’s Left Bank bookshop, Shakespeare & Company. Passing through its doors were all the big names (Joyce, Pound, Eliot, etc.), along with a host of other writers, artists, and musicians. Although the historical content is invaluable to any literary enthusiast, the book’s greatest asset is that it is written so competently. Covering such a wide span of time, and involving so many people, the book could easily have become a collection of entertaining anecdotal fragments with little style or organization. Fitch maintains a steady narrative throughout, compelling in both its breadth as well as attention to detail. It is also an engaging and exciting read—as Beach meets with the literary and artistic lights of her day, so does the reader. We feel empathy, energy and enjoyment in the vast panorama of the scene itself, and whether Fitch is describing the high-jinks of the Surrealists or the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses, the reader feels placed in the middle of the action.

Of course, for its detailed description of the publication history of Ulysses alone, the book should be added to the canon of Joyce studies. The quest for a printer who will take on the job all others deem “obscene,” trying to locate people who will even type up the manuscript, dealing with the incessant additions and corrections Joyce made at every stage . . . it seems that the only thing more interesting and difficult that Ulysses itself were the travails of getting it published! It also focuses on the writing and eventual publication of Finnegans Wake. Fitch relates how Joyce and his army of scouts and assistants (Samuel Beckett among them) hunted down obscure words and references, while the first generation of Joyce exegetes (Stuart Gilbert, et. al) offered Joyce enthusiastic encouragement amidst the hostile bafflement of new enemies and old friend such as Ezra Pound.

This leads into perhaps the slowest part of the book, the pre-War Thirties. Having lost some of the wild energy of the Twenties, Shakespeare & Company began to attract a new generation of writers—Jean-Paul Sarte and Simone de Beauvoir among others—but never quite regained its initial glory. By the time World War II breaks out, the book ends in a minor key, recounting how many of the Left Bank’s brilliant minds perished in the war. This is followed by sad endnotes—Joyce’s disillusionment and eventual passing, Pound’s dip into fascism, and finally Beach’s own death.

I cannot stress enough the marvelous tone, pacing, and overall execution that Fitch achieves in this wonderful work. Fitch places the reader directly in the middle of this exciting time, with its flourishing intellects, renaissance of literary styles, and revolutionary blending of arts and cultures. That one feels personally touched by this greatness is a tribute to Fitch and a hearty recommendation for his book.

Nora: The Real Life of Molly Bloom

Nora: The Real Life of Molly Bloom

By Brenda Maddox

First Edition: Houghton Mifflin, 1988

Current: Mariner Books, 2000

Available online at: Internet Archive

Brenda Maddox (1932-2019) was an American-born writer and book critic who lived in Wales with her husband, Sir John Maddox, a British scientist who edited Nature magazine. Although her books cover subjects ranging from Victorian geology to her own personal life, Lady Maddox was primarily a biographer, and has written about W.B. Yeats, D.H. Lawrence, Elizabeth Taylor, Rosalind Franklin, George Eliot, James Watson, and Margaret Thatcher. Many of these biographies focus on their subjects’ unusual romantic relationships. Published in 1988, Nora: The Real Life of Molly Bloom was the first extensive biography of Joyce’s wife, Nora Barnacle. (The British title was simply, Nora: A Biography of Nora Joyce.) The book was a finalist for the National Book Award, and remains Maddox’s best-selling work. In 2000, Nora was transformed into a full-length motion picture starring Susan Lynch as Nora Barnacle and Ewan McGregor as James Joyce. Maddox’s book was re-issued with a new cover featuring a still from the movie.

Rebecca Sullivan: In 1904, having known each other for only three months, a young woman named Nora Barnacle and a not-yet famous writer named James Joyce left Ireland. He had refused to marry her, proclaiming his adamant opposition both to the institution of marriage and to the institution that would solemnize their vows. Yet this unholy exit from a struggling land was the beginning of an amazing partnership—and eventual marriage—which endured for thirty-seven years. Brenda Maddox’s biography of Nora Joyce is a remarkable social history, revealing much about Irish life and character and providing a vivid reconstruction of the elegantly vagabond existence of the perversely charming and brilliant writer and his little Irish entourage. The book is about Nora, who emerges as a unique and fascinating character, but ultimately it is a portrait of her relationship with James Joyce and of the impact she had on his work. Nora is Joyce’s “Portable Ireland,” and he uses her words, her experiences, and her soul to create his female characters. Brenda Maddox presents the evolution of Nora from the unsophisticated but not simple Irish maid to the worldly woman whom Joyce introduces as Molly Bloom in Ulysses and Gretta Conroy in “The Dead.” Their union is complicated, committed, and sometimes shocking, yet Nora emerges as a warm, intelligent woman who was a powerful force behind one of the great literary figures of the twentieth century.

John Stanislaus Joyce: The Voluminous Life and Genius of James Joyce’s Father

John Stanislaus Joyce: The Voluminous Life and Genius of James Joyce’s Father

By John Wyse Jackson & Peter Costello

St. Martin’s Press, 1998

Available online at: Internet Archive

Born in Kilkenny, John Wyse Jackson (1953-2020) was an antiquarian bookseller and writer. He has written extensively about Flann O’Brien and Oscar Wilde, penned a biography of John Lennon, and collaborated with Bernard McGinley to produce the lavishly annotated James Joyce’s Dubliners: The Illustrated Edition. In 1998 Jackson teamed up with Peter Costello (James Joyce: The Years of Growth) to write a comprehensive biography of James Joyce’s father. Kirkus published an informative summary in 1998:

In this exhaustive work, Dubliners and Joyce scholars Jackson and Costello (the latter the author of James Joyce, 1993) portray the Joyces’ paterfamilias as a colorful figure from a fading world, and his orbit as a priceless source for much of James’ fiction. Write Jackson and Costello, “in a real sense John Stanislaus Joyce is the ur-author of Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.” A supporter of Irish nationalist Charles Stewart Parnell and Irish home rule, John Stanislaus Joyce (1849-1931) is described as his son’s primary literary inspiration and as providing the context to almost everything he wrote. The only son of James Augustine Joyce and Ellen O’Connell, John entered Queen’s College, Cork, in 1867, but he would not complete his higher education. He began his professional career as an accountant in Cork. Money was a lifelong struggle; though he was never quite officially bankrupt, the family moved residences, as the authors show, with shocking frequency, and John changed employers constantly. A prideful father, John watched his eldest (and favored) son, James, abandon his medical studies in Paris for journalism and later fiction writing. James, they say, was always “eager to draw on his father’s memories and extravagant idioms,” including a deathbed interview arranged to create lasting documentation of John’s world. (James also built up character sketches in his notes, some reproduced here, for use in his fiction.) Jackson and Costello are likewise determined to locate, or at least observe, James’s countless real-life sources—names, places, characters, anecdotes—in his father’s “voluminous” life and milieu. They recount the aging John’s bestowing custodianship of the Joyce family portraits to his son in a symbolic passing of the family torch. Later, in Zurich, James would “turn memory into literature.” A readable biography, undeniably a useful contribution to Joyce studies, though overlong and over-detailed for most casual fans.

—Copyright ©1998, Kirkus Associates, LP.

Lucia Joyce: To Dance In the Wake

Lucia Joyce: To Dance In the Wake

By Carol Loeb Shloss

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2003

Picador, 2005

Available online at: Internet Archive

Carol Loeb Schloss is an English professor at Stanford University. She has written books on Flannery O’Connor and American photography; but her most famous work is Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake, a biography of James Joyce’s daughter. It’s a controversial book, frequently criticized for its romanticized portrayal of Lucia’s schizophrenia. Schloss depicts Lucia as a victim of her family’s shame, a secret muse Joyce vampirically drained for inspiration to write Finnegans Wake. This portrayal ran afoul of the Joyce Estate, and Stephen Joyce demanded FS&G delete certain key elements of Schloss’ research before printing. The publisher complied. (Though whether they broke up the type and burned the copies is a matter of speculation.)

When reviewers subsequently pilloried Schloss for essentially “making things up” to support her thesis, she created a “author’s cut” of the book on a privately-owned Web site. The Joyce estate attacked her legally, and Shloss responded with a suit of her own, accusing Stephen Joyce of attempting to “interfere with [her] research, to stop publication of her book, to damage her relationship with her employer, and to misuse the copyrights they control.” The suit was settled in 2009, and Schloss was awarded $240,000 in attorney fees. Her legal statement pulled no punches: “the cost of litigating this case, which was substantial, was a direct result of the Estate’s assiduous and energetic efforts to prevent Shloss from exercising the rights the U.S. copyright laws encourage, and its ‘scorched earth’ approach to litigating the early stages of the case to see if it could bully Shloss into capitulation.” It was a hard-fought victory against the much loathed (and feared) Joyce Estate, and a powerful statement in support of academic freedom. Unfortunately Shloss was too exhausted by the affair to push a revised edition into print. Hopefully one day Joyce fans will be able to read the definitive version of this fascinating and provocative biography!

Publisher’s Description: Most accounts of James Joyce’s family portray Lucia Joyce as the mad daughter of a man of genius, a difficult burden. But in this important new book, Carol Loeb Shloss reveals a different, more dramatic truth: Lucia’s father not only loved her but shared with her a deep creative bond. His daughter, Joyce wrote, had a mind “as clear and as unsparing as the lightning.” Born at a pauper’s hospital in Trieste in 1907, educated haphazardly in Italy, Switzerland, and Paris as her penniless father pursued his art, Lucia was determined to strike out on her own. She chose dance as her medium, pursuing her studies in an art form very different from the literary ones celebrated in the Joyce circle and emerging, to Joyce’s amazement, as a harbinger of modern expressive dance in Paris. He described her then as a wild, beautiful, “fantastic being” who spoke to “a curious abbreviated language of her own” that he instinctively understood—for in fact it was his as well. The family’s only reader of Joyce’s work, Lucia was a child of the imaginative realms her father created. Even after emotional turmoil wreaked havoc with her and she was hospitalized in the 1930s, Joyce saw in her a life lived in tandem with his own. Though most of the documents about Lucia have been destroyed, Shloss has painstakingly reconstructed the poignant complexities of her life—and with them a vital episode in the early history of psychiatry, for in Joyce’s efforts to help his daughter he sought out Europe’s most advanced doctors, including Jung. Lucia emerges in Shloss’s account as a gifted, if thwarted, artist in her own right, a child who became her father’s tragic muse.

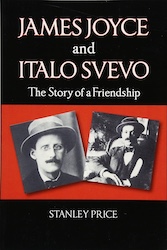

James Joyce and Italo Svevo: The Story of a Friendship

James Joyce and Italo Svevo: The Story of a Friendship

By Stanley Price

Somerville Press, 2016

While living in Trieste, James Joyce gave English lessons to Aron Hector “Ettore” Schmitz. A non-observant Jew who became a non-practicing Catholic, Schmitz was also a writer, having published two unsuccessful novels under the pen-name Italo Svevo. The two men struck up a friendship, and Joyce encouraged Schmitz to keep writing. He would eventually publish a classic of Italian modernism in 1923, La coscienza di Zeno, famous for its “unreliable narrator.” Meanwhile, Joyce would incorporate some of his friend’s characteristics into the indomitable Leopold Bloom.

Terence Killeen gave Price’s book a favorable review in the Irish Times:

Price brings a freshness of perception and considerable extra detail to the story of this relationship. He charts the parallels between the lives of these two figures, explores their relationship with sympathy, understanding and humour; commenting on Schmitz’s efforts to solace himself with music for his lack of success as a writer, he writes: ‘Joyce and Svevo found consolation for their frustrations in very different sorts of bars.’ His book is a fitting tribute to one of the most productive relationships of both writers’ lives. One might say that Joyce owed Svevo for his role in the creation of Leopold Bloom, and he repaid that debt handsomely by his part in ensuring Svevo’s lasting fame. Joyce, moreover, borrowed Livia Schmitz’s beautiful first name, and her hair, for the Anna Livia of Finnegans Wake.

Joyce Biography

[Main Page | Biographical Sketch | Chronology | Joyce Biographies | Family & Associates | Memoirs & Photos | Letters | Dublin]

Authors: Allen B. Ruch, Bob Williams, Rebecca Sullivan & Tim Miller

Last Modified: 12 June 2024

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com