Joyce Audio – Joyce in His Own Voice

- At November 07, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Joyce Audio: Joyce in His Own Voice

Hear: Joyce reading from Ulysses

Audio PlayerHear: Joyce reading from Anna Livia Plurabelle (Finnegans Wake)

Audio PlayerIn the 1920s, James Joyce made two recordings of himself reading from his works. The first was an excerpt from the “Aeolus” episode in Ulysses. The second was an excerpt from Anna Livia Plurabelle, a “tale” from Work in Progress that would later conclude Book I of Finnegans Wake. The history of these recordings is outlined below, largely drawn from Joyce’s own letters and the memoirs of Sylvia Beach. This is followed by descriptions of the recordings, information on where to obtain them, and additional resources for those interested in learning more.

The Joyce Recordings: A Brief History

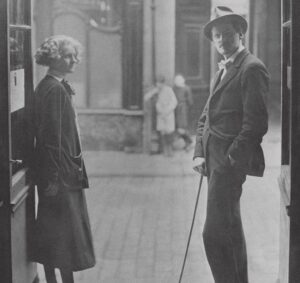

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in Paris

The 1924 Ulysses Recording

His Master’s Voice

In 1924, Sylvia Beach suggested to James Joyce that he record himself reading from Ulysses. As Beach recounts in her 1959 memoir, Shakespeare and Company:

In 1924, I went to the office of His Master’s Voice in Paris to ask them if they would record a reading by James Joyce from Ulysses. I was sent to Piero Coppola, who was in charge of musical records, but His Master’s Voice would agree to record the Joyce reading only if it were done at my expense. The record would not have their label on it, nor would it be listed in their catalogue.

Some recordings of writers had been done in England and in France as far back as 1913. Guillaume Apollinaire had made some recordings which are preserved in the archives of the Musée de la Parole. But in 1924, as Coppola said, there was no demand for anything but music. I accepted the terms of His Master’s Voice: thirty copies of the recording to be paid for on delivery. And that was the long and the short of it.

In contemporary letters to Harriet Shaw Weaver and French poet Valery Larbaud, Joyce suggests he’s going to read from the “Sirens” episode:

To HARRIET SHAW WEAVER

16 November 1924

8 Avenue Charles Floquet, Paris VII

Dear Miss Weaver: Many thanks for Penguin Island. I shall read it again in English. I hope you liked it.

I did not succeed in seeing Dr Borsch till last night. The very latest is that he is to do the operation on me on 27 instant—for cataract. I confess this novelty made me feel somewhat ill. He says I will regain my sight after it. Have I cataract as well? Or was he waiting for it to mature? I know nothing about this or what the results of such an operation are and I am too tired to ask any more questions. Ainsi soit-il.

In the meantime I am preparing for it by trying to learn a page of the Sirens for the record and by pulling down more earthwork. The gangs are now hammering on all sides. It is a bewildering business. I want to do as much as I can before the execution. Complications to right of me, complications to left of me, complex on the page before me, perplex in the pen beside me, duplex in the meandering eyes of me, stuplex on the face that reads me. And from time to time I lie back and listen to my hair growing white. . . .

To VALERY LARBAUD

MS. Bib. Munieipale, Vichy

20 November 1924

8 Avenue Charles Floquet, Paris VII

Dear Larbaud: Thanks for the typescript. It almost finishes the question but there are just two points I would like to discuss. Can Mrs Nebbia and yourself come here and have tea on Friday 29 at 4.30. We could discuss it then. Morel has done, it seems, 100 pages of Ulysse. I shall look up this matter of the German rights before you come. I am not free till the 28 as on the 27 I have to read part of the Sirens for a gramophone record.

There is bad news too. I have cataract. The doctor did not tell me till a few days ago. I am to be operated on the 31.? Et j’en ai marre!

Kind regards from us to Mrs Nebbia and yourself

Sincerely yours

JAMES JOYCE

At the last minute, Joyce changed his mind about his reading selection, switching from the “Sirens” episode to “Aeolus.” Beach describes the decision in her memoirs:

Joyce had chosen the speech in the Aeolus episode, the only passage that could be lifted out of Ulysses, he said, and the only one that was “declamatory” and therefore suitable for recital. He had made up his mind, he told me, that this would be his only reading from Ulysses.

I have an idea that it was not for declamatory reasons alone that he chose this passage from Aeolus. I believe that it expressed something he wanted said and preserved in his own voice. As it rings out—“he lifted his voice above it boldly”—it is more, one feels, than mere oratory.

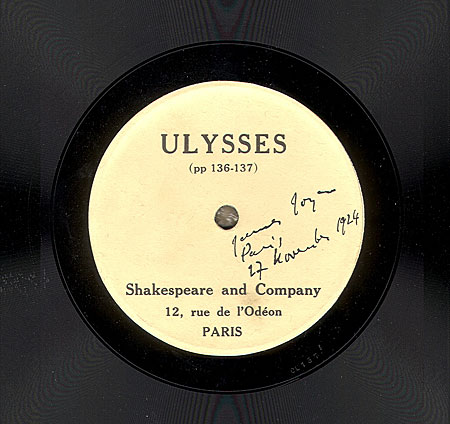

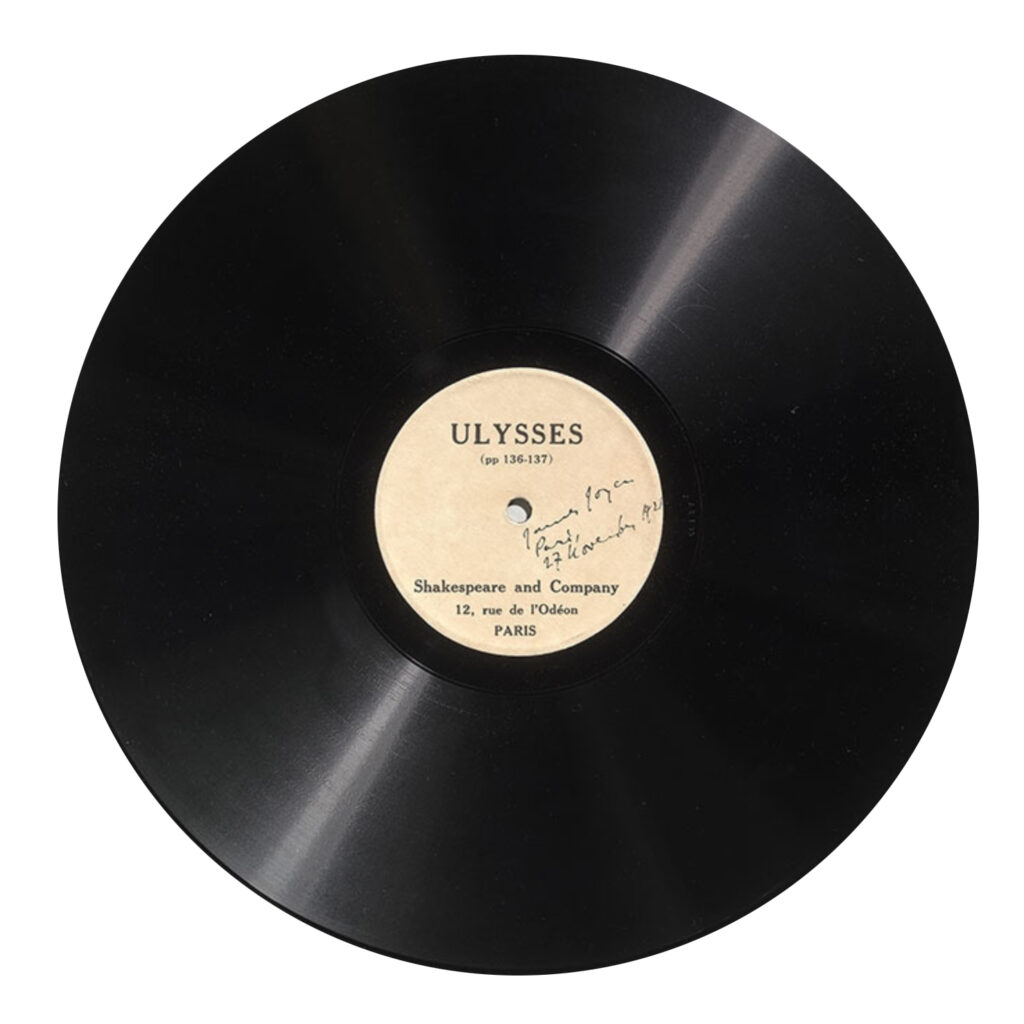

Suffering from a cataract and uncharacteristically anxious, Joyce made the recoding on 27 November 1924. Thirty copies of the 12-inch, 78-rpm record were pressed into shellac. As promised, the recording advertised “Shakespeare and Company” rather than HMV, and Joyce signed and dated each label.

From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

The Rarest Publication

The recording was considered little more than a novelty, and was not placed on sale—the copies were simply distributed among Joyce’s friends and associates. Unfortunately, neither Beach nor Joyce understood the recording process, and they failed to secure the master. As Beach explains,

How I regret that, owing to my ignorance of everything pertaining to recording, I didn’t do something about preserving the “master.” This was the rule with such records, I was told, but for some reason the precious “master” of the recording from Ulysses was destroyed. Recording was done in a rather primitive manner in those days, at least at the Paris branch of His Master’s Voice, and Ogden was right, the Ulysses record was not a success technically. All the same, it is the only recording of Joyce himself reading from Ulysses, and it is my favorite of the two. [Ogden and the second recording are explained below.]

The Ulysses record was not at all a commercial venture. I handed over most of the thirty copies to Joyce for distribution among his family and friends, and sold none until, years later, when I was hard up, I did set and get a stiff price for one or two I had left.

Discouraged by the experts at the office of the successors to His Master’s Voice in Paris, and those of the B.B.C. in London, I gave up the attempt to have the record “re-pressed”—which I believe is the term. I gave my permission to the B.B.C. to make a recording of my record, the last I possessed, for the purpose of broadcasting it on W. R. Rodgers’ Joyce program, in which Adrienne Monnier and I took part.

Anyone who wishes to hear the Ulysses record can do so at the Musée de la Parole in Paris, where, thanks to the suggestion of my California friend Philias Lalanne, Joyce’s reading is preserved among those of some of the great French writers.

Most of the original records have broken or disintegrated over the years. As suggested by the Morgan Library, which displayed a copy of the record during its “One Hundred Years of Ulysses” exhibition, “to this day, it remains Joyce and Beach’s rarest ‘publication.’”

The 1929 Anna Livia Plurabelle Recording

The Tyranny of Grammatical Good Form

One of the “family and friends” who heard the 1924 recording was the philosopher and linguist Charles Kay “C.K.” Ogden, the inventor of “Basic English.” An enthusiastic supporter of Joyce, Ogden had taken a curiously different tack on his own creative journey—he believed the English language could be distilled into 850 essential words! A fellow iconoclast, in 1909 Ogden established the Heretic Society of Cambridge to freely discuss matters of politics, religion, and science. The Society drew such thinkers as George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell, C.K. Chesterton, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and even Virginia Woolf. In 1912 Ogden founded Cambridge Magazine, which counted George Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy, and Siegfried Sassoon as contributors.

An “early adopter” of recording technology, Ogden believed that records had tremendous potential for the instruction of language. His “Orthological Institute” in Cambridge featured a suite of cutting-edge recording equipment, and had already recorded George Bernard Shaw. As Beach remarked in her memoirs, it was Odgen’s opinion that HMV botched the 1924 recording. He offered Joyce the chance to make a new recording at his more sophisticated studio in Cambridge.

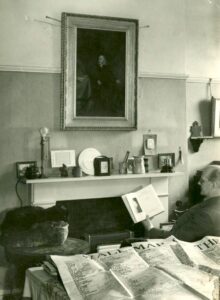

C.K. Ogden in his study. Photo from McMaster University Library

C.K. Ogden in his study. Photo from McMaster University Library

By that time, Joyce had moved on from Ulysses—well, aside from all the headaches involving errors, translations, legal concerns, and pirated copies!—and had begun writing Work in Progress, a series of linguistically adventurous episodes that would become Finnegans Wake. In 1928 Joyce published the most famous of these episodes, Anna Livia Plurabelle, the riversong that would later conclude Book I of Finnegans Wake. The following year Joyce published Tales Told of Shem and Shaun, subtitled as “Three Fragments from Work in Progress.” Prompted by Beach, Joyce asked C.K. Ogden to supply the preface. Published by the wonderfully-named Black Sun Press in Paris, the book included the famous “symbol of Joyce,” Portrait of the Author by Constantin Brancusi.

“Tales Told of Shem and Shawn,” with Brancusi’s “portrait” and Odgen’s preface. From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

“Tales Told of Shem and Shawn,” with Brancusi’s “portrait” and Odgen’s preface. From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Some Scheme About Making Records

The same month that saw the Parisian publication of Tales, Joyce visited the Orthological Institute to record himself reading from Anna Livia Plurabelle. Richard Ellmann describes the encounter in James Joyce, his massive biography published the same year as Beach’s memoirs and featuring the same Brancusi drawing:

In August 1929 the Joyces went to Bristol… They paid Claud Sykes a visit at Letchworth, and Joyce was glad to hear of a local resident named Gale who was like Earwicker; he succeded in obtaining a photograph of him. At Drinkwater’s suggestion, he consulted a London ophthalmologist, Dr. Euston. He found time also to record the last pages of Anna Livia for Ogden at the Orthological Institute; the pages had been prepared for him in half-inch letters, but the light in the studio was so weak that Joyce still could not read them. He had therefore to be prompted in a whisper throughout, his achievement being, as Ogden said, all the more remarkable.

Sylvia Beach goes into greater detail:

The Ulysses recording was “very bad,” according to my friend C. K. Ogden. The Meaning of Meaning by Mr. Ogden and I. A. Richards was much in demand at my bookshop. I had Mr. Ogden’s little Basic English books, too, and sometimes saw the inventor of this strait jacket for the English language. He was doing some recording of Bernard Shaw and others at the studio of the Orthological Society in Cambridge and was interested in experimenting with writers, mainly, I suspect, for language reasons. (Shaw was on Ogden’s side, couldn’t see what Joyce was after when there were already more words in the English language than one knew what to do with.) Mr. Ogden boasted that he had the two biggest recording machines in the world at his Cambridge studio and told me to send Joyce over to him for a real recording. And Joyce went over to Cambridge for the recording of “Anna Livia Plurabelle.”

So I brought these two together, the man who was liberating and expanding the English language and the one who was condensing it to a vocabulary of five hundred words. Their experiments went in opposite directions, but that didn’t prevent them from finding each other’s ideas interesting. Joyce would have starved on five or six hundred words, but he was quite amused by the Basic English version of “Anna Livia Plurabelle” that Ogden published in the review Psyche. I thought Ogden’s “translation” deprived the work of all its beauty; but Mr. Ogden and Mr. Richards were the only persons I knew about whose interest in the English language equaled that of Joyce, and when the Black Sun Press published the little volume Tales Told of Shem and Shaun, I suggested that C.K. Ogden be asked to do the preface.

How beautiful the “Anna Livia” recording is, and how amusing Joyce’s rendering of an Irish washerwoman’s brogue! This is a treasure we owe to C. K. Ogden and Basic English. Joyce, with his famous memory, must have known “Anna Livia” by heart. Nevertheless, he faltered at one place and, as in the Ulysses recording, they had to begin again.

Ogden gave me both the first and second versions. Joyce gave me the immense sheets on which Ogden had had “Anna Livia” printed in huge type so that the author—his sight was growing dimmer—could read it without effort. I wondered where Mr. Ogden had got hold of such big type, until my friend Maurice Saillet, examining it, told me that the corresponding pages in the book had been photographed and much enlarged. The “Anna Livia” recording was on both sides of the disc; the passage from Ulysses was contained on one. And it was the only recording from Ulysses that Joyce would consent to.

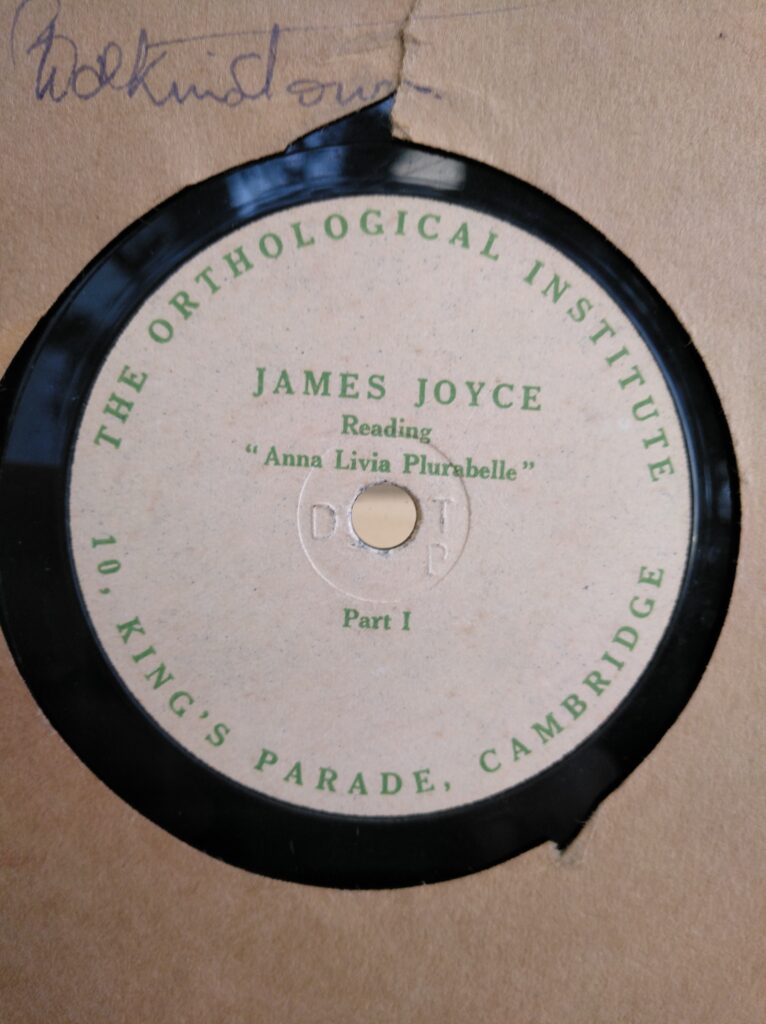

Like the Ulysses recording, the Cambridge record was a 12-inch, 78-rpm shellac album, but this one was double-sided, the reading divided into Part I and Part II. As Ogden had promised, the Cambridge recording was higher quality than the HMV record, and sold for £2 2s. When Faber & Faber published the first English edition of Anna Livia Plurabelle in June 1930, it contained an insert advertising “Mr Joyce’s own reading of the last four pages of Anna Livia Plurabelle” as produced by the Orthographical Institute.

From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

From the “Kelly” Collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Ghost Experience

Prior to giving them to Sylvia Beach, Joyce kept Ogden’s enlarged sheets at his Parisian apartment. On 30 November 1929, Sergei Eisenstein paid a visit to Joyce. The Russian fimmaker was particularly struck by Joyce’s poor vision, and described the meeting as a “ghost experience” on account of the dim lighting and shadows. After discussing Anna Livia Plurabelle, Joyce handed Eisenstein the “giant meter-wide sheet of paper, filled with gigantic lines of gigantic letters” and urged Eisenstein to follow along with the gramophone recording. Eisenstein recorded his impressions in his 1946 autobiography, Immoral Memories:

How in character that is with the author! How in tune with that magnifying glass with which he scans the microscopic convolutions of the mysteries of literary language! How symbolic for the path of his roaming along the winding inner movement of emotion and the inner structure of internal speech!

Although the Cambridge recording of Anna Livia Plurabelle sold out its first run, historical accounts of the process are somewhat muddled. The price was halved for the second run, but it seems the pressings were handled by HMV. In a letter dated 5 October 1930, Joyce complains about the disc—and Ogden’s apparent lack of sustained interest in the endeavor—to the wife of Joyce’s biographer, Herbert S. Gorman:

I cannot get any satisfaction about that A.L.P. disc and I wish Mr Gorman could bring the matter up in conversation if and when he meets T.S. [Eliot]. The idea was Ogden’s but he is now quite off it and a sale of 5 discs a year is absurd.

Nevertheless, Joyce was satisfied enough to recommend the process to James Stephens in a letter dated the following day, 6 October 1930:

I hope you got the A.L.P. disc I sent you safely. Perhaps you could see Ogden (address Royal Societies’ Club). He and T.S. Eliot have some scheme about making records of writers. The H.M.V. factory is not progressive enough. You ought to read or speak some of your work or perhaps we can still manage our 2-sided disc.

In 1951 the James Joyce Society of New York released a double-LP box set entitled “Meeting of the Joyce Society at the Gotham Book Mart, October 23rd, 1951—Finnegans Wake.” Produced by Folkways Records, the disc contained numerous readings and lectures, along with the 1929 Joyce recording. (The set also includes a reading by Joseph Campbell.) In 1954 Gotham Book Mart released a replica of the original two-sided 78 rpm. After that, the cat was out of the bag, and both Joycean recordings were subsequently released many times on vinyl, cassette, and compact disc. Of course, today these historic recordings are widely and freely available on the Internet.

Afterword: What about the “Argus Book Shop” Pressing?

There is some bibliographical confusion as to whether or not Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabelle recording was ever re-recorded by the Argus Book Shop in Chicago. After all, no less authorities than Slocum and Cahoon mention this “pressing” in their celebrated 1953 Bibliography of James Joyce, although they uncharacteristically offer no further details. After attempting to track down this “Argus” recording, I’ve come to the conclusion that it does not exist. It seems the confusion was created by something the Argus Book Shop did publish in 1935: a musical setting of Anna Livia Plurabelle, scored by Hazel Feldman for piano and voice. According to Feldman, she was inspired by hearing the 1929 recording of Joyce’s reading, and her score attempts to evoke the musicality of his voice. The score was published as Anna Livia Plurabelle, with “Text by James Joyce, Music by Hazel Feldman.” Limited to 350 copies signed by Feldman, it was accompanied by a pamphlet by Martin Ross entitled Music and James Joyce. To the best of my knowledge, Feldman’s piece has never been commercially recorded, and the Argus Book Shop—which did indeed have a loose relationship with Shakespeare and Company, once writing Sylvia Beach for a deluxe edition of Pomes Penyeach—never re-recorded or distributed Joyce’s Cambridge recording. It seems likely the initial error was Slocum and Cahoon’s, and has been simply replicated throughout various Joyce papers, Joycean Web sites, and articles about the recording.

The Recordings

Ulysses (pp. 136-137)

Ulysses (pp. 136-137)

Read by James Joyce

Shakespeare & Company, 1924

Recorded at HMV, Paris

Available at: Brazen Head MP3| YouTube | Amazon CD

The Ulysses reading is taken from the “Aeolus” episode. Joyce reads the second half of “IMPROMPTU” and most of “FROM THE FATHERS,” the scene where Professor MacHugh recites Gerald Fitzgibbon’s speech comparing the Irish to the Israelis under the rule of Egypt. Joyce does not read the text verbatim, but makes changes apparently on the fly, altering a few words, reorganizing long sentences, and simply omitting some sentences altogether. (The text printed below reflects Joyce’s reading as recorded, with all his changes intact.) The recording quality is poor, and Joyce’s voice is muffled under an unfortunate amount of hiss and static.

IMPROMPTU

[…]

He began:

—Mr Chairman, ladies and gentlemen: Great was my admiration in listening to the remarks addressed to the youth of Ireland a moment since by my learned friend. It seemed to me that I had been transported into a country far away from this country, into an age remote from this age, that I stood in ancient Egypt and that I was listening to the speech of a highpriest of that land addressed to the youthful Moses.

His listeners held their cigarettes poised to hear, their smoke ascending in frail stalks that flowered with his speech. Noble words coming. Look out. Could you try your hand at it yourself?

—And it seemed to me that I heard the voice of that Egyptian highpriest raised in a tone of like haughtiness and like pride. I heard his words and their meaning was revealed to me.

FROM THE FATHERS

And it was revealed to me that those things are good which yet are corrupted which neither if they were supremely good nor unless they were good could be corrupted. Ah, curse you! That’s saint Augustine.

—Why will you jews not accept our language, our religion and our culture? You are a tribe of nomad herdsmen: we are a mighty people. You have no cities nor no wealth: our cities are hives of humanity and our galleys, trireme and quadrireme, laden with all manner merchandise furrow the waters of the known globe. You have but emerged from primitive conditions: we have a literature, a priesthood, an agelong history and a polity.

Nile.

Child, man, effigy. By the Nilebank the babemaries kneel, cradle of bulrushes: a man supple in combat: stonehorned, stonebearded, heart of stone.

—You pray to a local and obscure idol: our temples, majestic and mysterious, are the abodes of Isis and Osiris, of Horus and Ammon Ra. Yours serfdom, awe and humbleness: ours thunder and the seas. Israel is weak and few are her children: Egypt is an host and terrible are her arms. Vagrants and daylabourers are you called: the world trembles at our name.

A dumb belch of hunger cleft his speech. He lifted his voice above it boldly:

—But, ladies and gentlemen, had the youthful Moses listened to and accepted that view of life, had he bowed his head and bowed his will and bowed his spirit before that arrogant admonition he would never have led the chosen people out of their house of bondage, nor followed the pillar of the cloud by day. He would never have spoken with the Eternal on Sinai’s mountaintop nor ever have come down with the light of inspiration shining in his countenance and bearing in his arms the tables of the law, graven in the language of the outlaw.

James Joyce Reading Anna Livia Plurabelle

James Joyce Reading “Anna Livia Plurabelle”

Read by James Joyce

Orthological Language Institute, 1929

Recorded at Orthological Language Institute, Cambridge

Available at: Brazen Head MP3 | YouTube | Amazon CD

While Joyce speaks softly, this recording is higher in quality than the HMV Ulysses, and it’s a pure delight to hear Joyce lilting his way through the Wakean language of his own invention. As with his reading of Ulysses, Joyce makes a few subtle changes to the text as he reads; but whether those were intentional or products of his failing eyesight remains a mystery. The text below is faithful to Joyce’s recording rather than the source material:

Well, you know or don’t you kennet or haven’t I told you every telling has a tailing and that’s the he and the she of it. Look, look, the dusk is growing. My branches lofty are taking root. And my cold cher’s gone ashley. Fielhur? Filou! What age is at? Its saon is late. ‘Tis endless now senne eye or erewone last saw Waterhouse’s clogh. They took it asunder, I hurd thum sigh. When will they reassemble it? O, my back, my back, my bach! I’d want to go to Aches-les-Pains. Pingpong! There’s the Belle for Sexaloitez! And Concepta de Send-us-pray! Pang! Wring out the clothes! Wring in the dew! Godavari, vert the showers! And grant thaya grace! Aman. Will we spread them here now? Ay, we will. Flip! Spread on your bank and I’ll spread mine on mine. Flep! It’s what I’m doing. Spread! It’s churning chill. Der went is rising. I’ll lay a few stones on the hostel sheets. A man and his bride embraced between them. Else I’d have folded and sprinkled them only. And I’ll tie my butcher’s apron here. It’s suety yet. The strollers will pass it by. Six shifts, ten kerchiefs, nine to hold to the fire and one for the code, the convent napkins twelve, one baby’s shawl. Good mother Jossiph knows, she said. Whose had? Mutter snores? Deataceas! Wharnow are alle her childer, say? In kingdome gone or power to come or gloria be to them farther? Allalivial, allalluvial! Some here, more no more, more again lost alla stranger. I’ve heard tell that same brooch of the Shannons was married into a family in Spain. And all the Dunders de Dunnes in Markland’s Vineland beyond Brendan’s herring pool takes number nine in yangsee’s hats. And one of Biddy’s beads went bobbling till she rounded up lost histereve with a marigold and a cobbler’s candle in a side strain of a main drain of a manzinahurries off Bachelor’s Walk. But all that’s left to the last of the Meaghers in the loup of the years prefixed and between is one kneebuckle and two hooks in the front. Do you tell me that now? I do in troth. Orara por Orbe and poor Las Animas! Ussa, Ulla, we’re umbas all! Mezha, didn’t you hear it a deluge of times, ufer and ufer, respund to spond? You deed, you deed! I need, I need! It’s that irrawaddyng I’ve stoke in my aars. It all but husheth the lethest zswound. Oronoko! What’s your trouble? Is that the great Finnleader himself in his joakimono on his statue riding the high horse there forehengist? Father of Otters, it is himself! Yonne there! Isset that? On Fallareen Common? You’re thinking of Astley’s Amiptheayter where the bobby restrained you making sugarstuck pouts to the ghostwhite horse of the Peppers. Throw the cobwebs from your eyes, woman, and spread your washing proper. It’s well I know your sort of slop. Flap! Ireland sober is Ireland stiff. Lord help you, Maria, full of grease, the load is with me! Your prayers, I sonht zo! Madammangut! Were you lifting your elbow, tell us, glazy cheeks, in Conway’s Carrigacurra canteen? Was I what, hobbledyhips? Flop! Your rere gait’s creakorhueman bitts your butts disagrees. Amn’t I up since the damp dawn, marthared mary allacook, with Corrigan’s pulse and varicoarse veins, my pramaxle smashed, Alice Jane in decline and my oneeyed mongrel twice run over, soaking and bleaching boiler rags, and sweating cold, a widow like me, for to deck my tennis champion son, the laundryman with the lavandier flannerls? You won your limpopo limp from the husky hussars when Collars and Cuffs was heir to the town and your slur gave the stink to Carlow. Holy Scamander, I sar it again! Near the golden falls. Icis on us! Seints of light! Zezere! Subdue your noise, you hamble creature! What is it but a blackburry growth on the dwyergray ass them four old coldgers owns. Are you meanem Tarpey and Lyons and Gregory? I meyne now, thank all, the four of them, and the roar of them, that draves that stray in the mist and old Johnny MacDougal along with them. Is that the Poolbeg flasher beyant, pharphar, or a fireboat coasting nyar the Kishtna or a glow I behold within a hedge or my Garry come back from the Indies? Wait till the honeying of the lune, love! Die eve, little eve, die! We see that wonder in your eye. We’ll meet again, we’ll part once more. The spot I’ll seek if the hour you’ll find. My chart shines high where the blue milk’s upset. Forgivemequick, I’m going! Bubye! And you, pluck your watch, forgetmenot. Your evenlode. So save to jurna’s end! My sights are swimming thicker on me by the shadows to this place. I sow home slowly now by own way, moyvalley way. Towy I too, rathmine.

Ah, but she was the queer old skeowsha anyhow, Anna Livia, trinkettoes! And sure he was the quare old buntz too, Dear Dirty Dumpling, foostherfather of fingalls and dotthergills. Gaffer and gammer we’re all their gangsters. Hadn’t he seven dams to wive him? And every dam had her seven crutches. And every crutch had its seven hues. And each hue had a differing cry. Sudds for me and supper for you and the doctor’s bill for Joe John. Befor! Bifur! He married his markets, cheap by foul, I know, like any Etrurian Catholic Heathen, in their plinky lemony creamy birnies and their turkiss indienne mauves. But at milkidmass who was the spouse? Then all that was was fair. Tys Elvenland! Teems of times and happy returns. The seim anew. Ordovico or viricordo. Anna was, Livia is, Plurabelle’s to be. Northmen’s thing made southfolk’s place but howmulty plurators made eachone in person? Latin me that, my trinity scholard, out of eure sanscreed into oure eryan. Hircus Civis Eblanensis! He had buckgoat paps on him, soft ones for orphans. Ho, Lord! Twins of his bosom. Lord save us! And ho! Hey? What all men? Hot? His tittering daughters of. Whawk?

Can’t hear with the waters of. The chittering waters of. Flittering bats, fieldmice bawk talk. Ho! Are you not gone ahome? What Thom Malone? Can’t hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying waters of. Ho, talk save us! My foos won’t moos. I feel as old as yonder elm. A tale told of Shaun or Shem? All Livia’s daughtersons. Dark hawks hear us. My ho head halls. I feel as heavy as yonder stone. Tell me of John or Shaun? Who were Shem and Shaun the living sons or daughters of? Night now! Tell me, tell me, tell me, elm! Night night! Telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night!

Bibliography

Beach, Sylvia. Shakespeare and Company: The Story of an American Bookshop in Paris. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1959.

Cornwell, Neil. James Joyce and the Russians. Palgrave Macmillan, 1992.

Curtin, Adrian. “Hearing Joyce Speak: The Phonograph Recordings of Aeolus and Anna Livia Plurabelle as Audiotexts.” James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Winter 2009), pp. 269-284.

Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce. Oxford University Press, 1959.

Joyce, James. Edited by Stuart Gilbert & Richard Ellmann. Letters of James Joyce, Vol. I, II, & III. Faber and Faber/Viking, 1966.

Loukopoulou, Elena. “Joyce’s Progress Through London: Conquering the English Publishing Market.” James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 4 (Summer 2011), pp. 683-710.

Murphet, Julian; Helen Groth & Penelope Hone, eds. Sounding Modernism: Rhythm and Sonic Mediation in Modern Literature and Film. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

Sailer, Susan Shaw. “Universalizing Languages: Finnegans Wake Meets Basic English.” James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Summer, 1999), pp. 853-868.

Slocum, John J. and Herbert Cahoon. A Bibliography of James Joyce (1882–1941). Yale University Press, 1953.

Tóibín, Colm, ed. One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Penn State University Press, 2022.

Werner, Gösta and Erik Gunnemark. “James Joyce and Sergej Eisenstein.” James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Spring, 1990), pp. 491-507.

Additional Information

Joyce’s Recording of Ulysses

From the stellar “One Hundred Years of Ulysses” Exhibit at the Morgan Library Museum in New York City.

Joyce’s Recording of Anna Livia Plurabelle

From the stellar “One Hundred Years of Ulysses” Exhibit at the Morgan Library Museum in New York City.

Joyce’s ALP Notes to Ogden

Peter Chrisp’s FW blog features the explanatory notes on Anna Livia Plurabelle Joyce sent to C.K. Ogden, who published them in Psyche magazine, April 1932, vol XII, no. 4, pp.86-95.

Sounds Difficult: James Joyce and Modernism’s Recorded Legacy

Damien Keane, “Sounding Out!” Blog. An interesting essay about Joyce’s ALP recording and the composer Hazel Feldman.

Joyce Audio

[Main Page | His Own Voice | Collections | Dubliners | Portrait | Ulysses | Finnegans Wake | Drama & Poetry | Biography & Criticism | Miscellany]

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 7 January 2023

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com