Muzzle Rifles

- At December 20, 2016

- By Great Quail

- In Armory, Deadlands

0

0

Rifles Part I. Muzzles, Muskets & Minié Balls

Loading a Flintlock Rifle

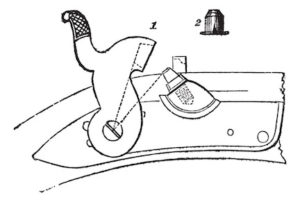

For the first part of the nineteenth century, professional armies fought with the same smooth-bore flintlock muskets as their fathers and grandfathers. It generally takes an experienced soldier between twenty and thirty seconds to properly load a flintlock musket. First, the user has to unseal his pre-measured cartridge of gunpowder, which is usually contained in a paper or linen packet which is bitten open. (Because of the salty nature of gunpowder, this builds up a terrible thirst over the course of a battle, making potable water an essential part of any armed conflict.) Once the gunpowder is poured into the muzzle, the shooter inserts the lead ball, which is encased in a lubricated bit of cloth called “wadding.” Pulling the ramrod from its forestock slot, the shooter tamps the ball home, ensuring firm contact with the propellant charge. The ramrod is then returned to the forestock—unless a panicked soldier leaves it inside the barrel, to be fired along with the bullet!

To fire the musket, the hammer is pulled to half-cock. A small pinch of gunpowder is placed in the “priming pan” located on the right side of the musket. The pan is closed to secure the primer, which brings a metal flange called the “frizzen” into striking position in front of the hammer. The hammer is fully cocked, the musket is aimed, and the trigger is pulled. The hammer dashes the flint against the frizzen, simultaneously creating a spark and pushing open the pan to expose the primer. The priming powder ignites, sending its charge through a flash hole into the chamber to explode the main charge of gunpowder. The lead ball is propelled from the barrel in a cloud of gunsmoke and burning wadding into the heart of the unlucky redcoat, voltigeur, Mysorean rocketeer, Fenian rebel, Mohawk warrior, etc. Because smoothbore muskets have limited effective ranges, the general tactic is to fire a few volleys, fix the bayonet, and rush in for close-quarters combat.

Caplocks

Caplocks

In the 1840s, flintlocks were gradually replaced by percussion locks, or “caplocks.” These firearms are primed using a percussion cap containing an explosive charge of mercury fulminate. To fire a caplock rifle, a percussion cap is placed on a hollow metal “nipple” or “cone” located beneath the hammer. When the trigger is pulled, the hammer strikes the percussion cap, which sends its charge into the breech to ignite the gunpowder. Alternately, the hammer may activate a concealed firing pin rather than directly striking the percussion cap.

Quick Reloading

During particularly frenzied moments, a muzzle-loader can be loaded more quickly by spitting the ball into the barrel without using wadding, firmly tapping the butt onto the ground to seat the ball, and then firing as usual. The lack of wadding decreases accuracy, but skipping the ramrod reduces the loading time by one full action round.

Buck and Ball

Soldiers equipped with muzzle-loaders may use a “buck and ball” load, in which three to six shotgun pellets are positioned in front of a standard caliber bullet. This practice not only adds to the damage caused by a well-aimed shot, but helps increase the average hit ratio when a volley is fired. In game terms, a muzzle-loader shotted with “buck and ball” adds 1d6 DAM to its standard damage rating, but only when striking a target within “Short” range.

Fouling the Barrel

For obvious reasons, black powder weapons must be cleaned regularly, as powder residue in the barrel seriously degrades the accuracy of the firearm. This is usually done by swabbing the barrel with hot water; but if no water is available, a soldier can always urinate down his barrel instead! As the barrel becomes increasingly more fouled, it takes an additional action round to load the firearm, and a –1 accuracy penalty is applied to all Shooting rolls.

Rifling

Aside from trading flint-and-frizzen for percussion caps, the other important innovation to mid-century musketry was “rifling.” A rifled musket has spiral grooves engraved inside its barrel. These grooves impart angular momentum onto the projectile as it leaves the muzzle, acting to stabilize the bullet and increasing its velocity, range, and accuracy. Although effective rifles were developed during Napoleonic times, they were notoriously difficult to maintain. Because of the “lands and grooves” of the rifling, the “windage”—the space between the projectile and the bore—had to be eliminated, so bullets were wrapped in greased patches of leather or linen before they were rammed home. This made rifles harder to load and clean, so they were placed only in the hands of specially-trained squads, Daniel Morgan’s Riflemen, Jefferson Davis’ Mississippi Rifles, or the British “Greenjackets” of Richard Sharpe fame.

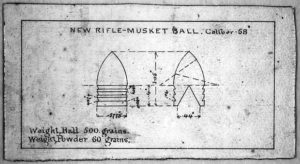

The Minié Ball

It was not until the invention of the Minié ball in 1849 that rifles became commonplace. Designed by French captain Claude-Étienne Minié and refined by James Burton of Harpers Ferry Armory, the Minié ball is a conical-shaped bullet with a hollow base, small enough to load quickly but designed to expand upon firing. This allows the heated bullet to grip the barrel’s rifling and achieve maximum spin as it departs the muzzle. Responsible for much of the devastation during the early Civil War, rifles equipped with Minié balls were first widely used by the British during the Crimean War. Because of their large caliber and their (by modern standards) relatively slow velocity, Minié balls inflict incredible amounts of damage to human flesh—one of the reasons that Civil War doctors were forced to perform so many amputations.

The Armory: Muzzle-Loaders

Long Rifle, “Pennsylvania Rifle,” “Kentucky Rifle”

1700s–1800s, USA, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .25 to .60, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d4 to 2d12, STR d8, Uncommon.

The American love affair with the rifle started long before the Declaration of Independence was signed, and has its origins among German immigrants, who brought their superior rifling techniques to the New World when they settled in Pennsylvania. Looking to arm themselves against the wildness of the American frontier, these gunsmiths proudly established the tradition of the American Long Rifle. Although their handcrafted firearms were originally known as “Pennsylvania” rifles, as pioneers followed Daniel Boone into the west, they acquired the more enduring, if less accurate, name of “Kentucky” rifles. Designed for a wide range of calibers, Kentucky rifles are renowned for the length of their barrels, a characteristic that empowers their treasured accuracy. Indeed, there are examples of Kentucky rifles over seventy inches long and weighing ten pounds!

Intended to be passed down from one generation to the next, many Kentucky rifles are works of art, featuring polished stocks of curly maple, elaborate engravings, and decorative inlays. Most contain a patchbox in the stock, and the powder horn, leather shooting bag, and shoulder sling are often as ornately designed as the rifle they accompany. Although by 1876 most Kentucky rifles are found decorating somebody’s wall, more than a few trespassers, cattle rustlers, and stray Yankees have discovered their stubborn capacity to resist obsolescence.

Intended to be passed down from one generation to the next, many Kentucky rifles are works of art, featuring polished stocks of curly maple, elaborate engravings, and decorative inlays. Most contain a patchbox in the stock, and the powder horn, leather shooting bag, and shoulder sling are often as ornately designed as the rifle they accompany. Although by 1876 most Kentucky rifles are found decorating somebody’s wall, more than a few trespassers, cattle rustlers, and stray Yankees have discovered their stubborn capacity to resist obsolescence.

|

|

| Examples of powder horns and shooting bags | |

Charleville Musket

1717–1840, France, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .69, Range 9/90/180, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/4, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Uncommon.

Le fusil modèle 1766

Descended from the French hunting guns of the seventeenth century, the musket that would be carried by France’s soldiers for the next 120 years was first introduced as “le fusil modèle 1717.” In 1728, a third barrel band was added, and the “Charleville” musket attained the basic form it would possess all the way to the Napoleonic Wars. Exported to the American colonies, the modèle 1763 and modèle 1766 were used by colonists against the British, while the French soldiers who came over with General Rochambeau carried the new modèle 1777. Although these muskets were produced at four different locations, the Americans referred to them collectively as “Charlesville” muskets, after Charleville-Mézières, the main French armory in Ardennes. The name stuck, and even modern French sources refer to them as “fusils Charleville.”

The main competitor of the Charleville was the British “Brown Bess” musket. Because the smaller bore of the Charleville is closer in diameter to its .69 caliber ammunition, the Charleville is more accurate than the Brown Bess, but fouls quickly and is more difficult to load. However, the Charleville is sturdier than its British counterpart. Its three barrel bands reinforce the musket when the bayonet is attached, and during close-quarters combat, the patte de vache or “cow’s foot” stock may be used as a heavy cudgel.

Fusil modèle 1777

The most enduring model of Charleville musket was also the last, the modèle 1777, which carved a cheek-rest into the stock and introduced a handsome brass flash pan and bridle. The modèle 1777 persisted through three separate modifications, including a “correction” made by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1800 known as the “le fusil modèle 1777 corrigé en l’an IX.” With over seven million produced, the modèle 1777 was carried across Europe by Napoleon’s Grande Armée, and became the most widely-used musket in history. The modèle 1777 spawned numerous imitations, such as the Austrian Model 1798, the Prussian Model 1808, and the majority of American muskets rolling from the armories at Springfield and Harpers Ferry.

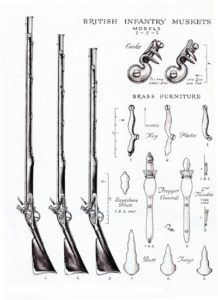

Land Pattern Flintlock Musket, “Brown Bess”

1722–1832, UK, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .75 bore/.69, .705, .72 balls, Range 8/75/150, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/4, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Common.

Produced for well over a century, the British Land Pattern musket was issued in many various lengths and designs, all of which were collectively referred to as the “Brown Bess.” Equipped with a .75 caliber bore, soldiers using the musket were generally issued smaller diameter balls, usually .69 or .705 caliber. This made loading considerably easier as the barrel became fouled; however, the additional windage between bore and barrel significantly reduced the accuracy of the musket. Although the French Charleville musket was more exact, the British soldiers trained to use the Brown Bess were less concerned with precision than with volume. Discharging their muskets in alternating volleys, a battalion of redcoats could sustain an almost continuous wall of fire at advancing troops, sending wave upon wave of lead balls crashing into the bodies of charging crapuads, highlanders, Teagues, Punjabis, and of course, upstart colonists.

Dating from before the Jacobite uprisings and used until well after the Napoleonic Wars, Brown Bess muskets were so prolific that many remained in circulation for decades after they were replaced by percussion rifles. Many later-period Brown Bess flintlocks were also converted to caplocks. The end of the Napoleonic Wars left Britain with a surplus of Brown Bess muskets, many of which were sold off around the world. They were used extensively by Mexican forces during the Mexican-American War, and some were sold to the Confederacy during the early days of the Civil War. Indeed, the 17th South Carolina equipped eight of their companies with percussion-converted Brown Bess muskets.

Nock Volley Gun

1779–1804, UK, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .46, Range 2/4/40, Capacity 7, Rate of Fire 1/7, DAM 6d10/3d10/1d10, STR d10, Very rare. Notes: Damage is not figured solely on caliber, as it’s unlikely all seven balls will fire, let alone strike the same target. Damage is calculated like a shotgun, with three separate DAM ratings tied to the S/E/L ranges.

Designed by British engineer James Wilson and produced by London gunsmith Henry Nock, the thirteen-pound “Nock gun” is an example of a volley gun, a firearm equipped with multiple barrels. The Nock gun sports seven 20” smooth-bore barrels, each of which must be separately loaded through the muzzle. When the shooter pulls the trigger, the primer ignites the charge in the central barrel, which sparks the surrounding six barrels through six internal vents. All seven barrels fire simultaneously, hurling a cloud of lead at the deeply unfortunate targets.

Designed by British engineer James Wilson and produced by London gunsmith Henry Nock, the thirteen-pound “Nock gun” is an example of a volley gun, a firearm equipped with multiple barrels. The Nock gun sports seven 20” smooth-bore barrels, each of which must be separately loaded through the muzzle. When the shooter pulls the trigger, the primer ignites the charge in the central barrel, which sparks the surrounding six barrels through six internal vents. All seven barrels fire simultaneously, hurling a cloud of lead at the deeply unfortunate targets.

Purchased by the Royal Navy, the Nock gun was a “deck sweeper,” a gun intended to be fired by sailors wishing to smartly repel unwanted boarders or tear up enemy rigging. In reality, it suffered from several flaws, not the least of which was its tremendous recoil—the backwards force exerted by discharging a fully-loaded Nock gun was known to dislocate a man’s shoulders, and could leave bruises on even the hardiest of shooters! Also, the gunpowder flash and burning wadding sometimes ignited the rigging of the very ship the user was trying to protect; and the act of tilting the gun downwards could cause loaded balls to become unseated or even roll out. Additionally, it was a rare volley that actually fired all seven barrels, and sometimes confused shooters would unwittingly double-shot unfired barrels upon reloading. Tedious to load, difficult to wield, and dangerous to use, the Nock gun went through a few iterations until the Royal Navy retired it in 1804.

Springfield Musket, U.S. Model 1795 to U.S. Model 1840

1795–1840, USA, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .69, Range 8/80/160, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/4, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Common.

U.S. Model 1816 Type II musket, based on the French fusil modèle 1777 “Charleville” musket

Named after America’s first national armory, “Springfield” muskets were actually produced all over the United States, from the federal armories at Springfield and Harpers Ferry to the workshops of dozens of private contractors, the largest of which was Eli Whitney in New Haven. To fully understand the history of this famous smoothbore musket—and the Springfield Civil War rifles that followed—some background on the history of Springfield Armory may be useful.

Springfield Armory

The United States’ most famous armory has its roots in the founding of the country. Recognizing the need for a federal arsenal, in 1777 George Washington traveled to Springfield, Massachusetts, to survey a bluff above the Connecticut River used as a training ground for local militia. Recommended to him by General Henry Knox, the location was ideal, sitting astride a nexus of rivers and roads, yet protected from naval attack by Enfield Falls. Agreeing with Knox that “the plain just above Springfield is perhaps one of the most proper spots on every account,” General Washington founded the “Arsenal at Springfield” with David Ames as its chief superintendent. As the Revolutionary War progressed, the Springfield Arsenal produced cartridges, repaired weapons, and stored munitions. After the Revolution, new barracks and workshops were added, and Springfield quickly emerged as the largest arsenal in the fledging United States of America.

The Model 1795 Musket

During the Revolution, the rebellious colonists were primarily armed with Brown Bess muskets, imported Charleville muskets, or their own personal “Pennsylvania” rifles. In 1794, Congress authorized funds for the construction of two federal armories—the first at Springfield Arsenal, and a the second at Harpers Ferry in Virginia. That same year, the government issued its first procurement order for American-made infantry muskets. Because many state arsenals possessed a ready supply of French components, these American-made muskets were to be based on the “Charleville Pattern,” or the fusil modèle 1763 familiar from the days of the Revolution. A year later, the first “Model 1795” muskets were produced at Springfield Armory. With Harpers Ferry still setting up shop, the government placed an additional order for 40,000 more muskets in 1798. This order was distributed among private contractors, each of whom was provided with a few Springfield muskets as examples. The new century opened with Harpers Ferry coming online, and soon “contract models” began supplementing the federal output—or not; as several contractors failed to fulfil their order. With no real system of standardization in place, these muskets varied in length, bore diameter, appearance, and overall quality. There were even differences between Harpers Ferry muskets and Springfield muskets. Despite their myriad differences, today these guns are collectively known as “Model 1795” muskets. Those considered to meet the highest standards of quality were the muskets produced at Springfield Armory, and those manufactured in New Haven by Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin.

U.S. Model 1795 musket with post-1799 eagle stamp. Based on the French fusil modèle 1763 “Charleville” musket

U.S. Model 1795 musket with post-1799 eagle stamp. Based on the French fusil modèle 1763 “Charleville” musket

Eli Whitney & Whitneyville

One of the fathers of American industrialism, Eli Whitney enters this story in 1798. Sensing an opportunity to test his theories about the advantages of mass production and interchangeable parts, the ambitious Whitney contracted with the government to make 10,000 muskets. Starting from scratch, Whitney spent the first two years building and equipping a factory at Mill Rock, Connecticut. Purchasing an old grist mill, he rebuilt the dam and used running water to power his tools. Whitney designed numerous specialized machines, established foundries and waterwheels, and constructed barracks to house his trained workers. His goal was to achieve a level of precision and standardization not found at the federal armories; or indeed, anywhere. Unfortunately, Whitney had spent all of his allotted time building machines instead of muskets, and was forced to travel to Washington D.C. to plead for more time. Impressed by Whitney’s ingenuity and sensing the potential of his methods, President Jefferson extended his contract, and by 1809, the “Whitneyville” factory delivered all 10,000 muskets. More than this, Whitney had laid the foundation for the mass production of firearms, with the War of 1812 ensuring a steady supply of work. After Eli Whitney retired, Whitneyville was passed to his sons, with his nephew Eli Whitney Blake taking over Harpers Ferry Armory in 1842. During this time, the Whitney family maintained a close relationship to Springfield Armory, with numerous Springfield patterns being mass-produced at Whitneyville. In time, New Haven became known as “America’s arsenal.” Samuel Colt used Whitneyville to manufacture his early revolvers in the 1830s, and in 1858, Eli Whitney III rented space to Oliver Winchester, who used it to produce his “New Haven Volcanic Arms” repeaters.

Springfield Muskets, U.S. Model 1812 to U.S. Model 1842

The armories at Springfield and Harpers Ferry continued to improve their musket patterns, and in 1799 Springfield Armory began stamping its lockplates with the now-iconic eagle. The years between 1795 and 1842 saw a wide variety of .69 caliber muskets, with increasing levels of standardization elevating the overall quality. Produced in time for a second war against Britain, the Model 1812 was based on the Charleville modèle 1777. The improved Model 1816 retained the basic Charleville pattern, with the Model 1822, Model 1835, Model 1840 muskets offering only minor improvements. The Model 1842 upgraded the Model 1840 to a caplock, and has the distinction of being Springfield’s last smoothbore musket. (It’s also the first Springfield pattern to be copied at South Carolina’s newly-established Palmetto Armory in 1851.) Starting with the Model 1855, rifles would become the order of the day. Nevertheless, many older Springfield muskets were converted to percussion locks, and more than a few were used in the first years of the Civil War.

Pattern 1800 Infantry Rifle, “Baker Rifle”

1801–1837, UK, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .625, Range 15/150/300, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Rare.

After being “exposed” to American Long Rifles during the Revolutionary War, the British decided to experiment with rifled muskets, and eventually settled upon Whitechapel gunsmith Ezekiel Baker’s design. Loosely based on the German “Jäger” rifle, Baker’s final model was a full 12” shorter than the Brown Bess, and featured a 30” barrel with seven rectangular grooves. A fairly handsome firearm, the Baker Rifle sports a raised cheek-piece, a scrolled brass trigger guard, and a brass patchbox containing the crucial cleaning kit. Like all rifles, the Baker took longer to load and required more attentive cleaning than a smoothbore musket, but its increased accuracy was more than adequate compensation to the “Chosen Men” who carried it. The rifle’s most famous advocate was Lt. Colonel Richard Sharpe, whose best marksman, Daniel Hagman, once brought down a French artillerist from 700 yards away.

Hawken Rifle

1823–1862, USA, muzzle-loaded flintlock/caplock. Caliber .50 to .69, Range 25/250/500, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d10 to 2d12, STR d6, Rare.

Produced by Jacob and Samuel Hawken in St. Louis, Missouri, “Hawken rifles” were among the most accurate and reliable examples of the “plains rifle,” a shorter descendent of the Kentucky long rifle. Prized by explorers, trappers, forty-niners, and buffalo hunters, each Hawken rifle is uniquely hand-crafted, and sports an octagonal barrel bored for any number of calibers ranging from .50 to .69. Their stocks are usually fashioned from maple or walnut, and often feature a curved “beaver’s tail” cheek piece. Most Hawken rifles are equipped with double-triggers, with the rear “set” trigger unlocking the front “hair” trigger, which may then be pulled using a minimal amount of pressure. This double-trigger configuration allows the shooter to customize his trigger-pull, which improves the accuracy of the rifle but reduces the chance for accidental discharge. Hawken rifles are quite beautiful but were tremendously expensive, and were favored by a diverse range of pioneers from Kit Carson to Porter Rockwell.

Jennings Repeating Flintlock Rifle

1821, USA, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .44, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 12, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d8, STR d8, Exceptionally rare. Notes: On a critical failure, a random number of remaining rounds discharge uncontrollably, each at a –4 Shooting penalty. This damages the barrel, which requires a workshop and a Repair roll to fix. If three or more rounds are accidentally discharged, the shooter takes 2d6 DAM. Reloading the Jennings takes three action rounds per load.

This bizarre muzzle-loader is the work of Isaiah Jennings of New York City, and is an example of a “superimposed” rifle, in which alternating sequences of powder and ball are loaded into the barrel and ignited through separate touchholes. The entire lockplate slides backwards along the frame as the loads are discharged from front to rear, with the metal ball behind each charge acting to seal the bore and prevent multiple discharge. The strange “centipede” appearance of the Jennings rifle is the result of its multiple touchhole covers. Each “apron” must be individually lifted to expose the touchhole and allow the lockplate to slide into position. An automatic priming system dispenses priming powder when the hammer is cocked.

Like many of Isaiah Jennings’ firearms, his Repeating Flintlock is built on a brass frame and features a skeleton-style buttstock inset with a wooden shoulder rest. Jennings produced only a few of these rifles, ranging in capacity from three to twelve shots. An exceptionally long rifle, the 21-inch octagonal barrel may be quickly removed by turning a screw where it joins the frame.

Ellis-Jennings Repeating Flintlock Rifle

1828–1829, USA, muzzle-loaded flintlock. Caliber .54, Range 10/100/200, Capacity 4, Rate of Fire 1/3, DAM 2d10, STR d8, Very rare. Notes: On a critical failure, a random number of remaining rounds discharge uncontrollably, each at a –4 Shooting penalty. This damages the barrel, which requires a workshop and a Repair roll to fix. If three or more rounds are accidentally discharged, the shooter takes 2d6 DAM. Reloading the Ellis-Jennings takes three action rounds per load.

This rifle was produced by Robert & J.D. Johnson of Middletown, Connecticut under contact from the New York State Militia to manufacture 520 repeating rifles using the Jennings patent. Built on the Model 1817 “Common Rifle,” the Ellis-Jennings features a self-priming system developed by Rueben Ellis of Albany, the contractor who secured the deal. Like its all-metal forefather, the Ellis-Jennings is a “superimposed” rifle, in which alternating sequences of powder and ball are loaded into the barrel and ignited through separate touchholes. The entire lockplate slides backwards along the frame as the loads are discharged from front to rear, with the metal ball behind each propellant charge acting to seal the bore and prevent multiple discharge. Each touchhole is fixed with a swiveling “apron” cover that must be individually lifted to expose the touchhole and allow the lockplate to slide into position.

Four-Shot Ellis-Jennings. Note the Ellis self-priming system attached to the pan.

The Ellis-Jennings Repeating Flintlock was considered an oddity even at the time, and history has not recorded whether all 520 models were delivered, let alone used in the field. The majority were chambered for four superimposed loads, but a few experimental models were produced using extended frames and chambered for ten superimposed loads. Rarer still was a twelve-shot “sporting” rifle, loaded from the breech and featuring a brass stock and barrel.

Kendall Underhammer Rifle

1835–1848, USA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .40 to .54, Range 30/300/600, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d6+1d8 to 2d10, STR d6, Very rare. Note: Kendall rifles produced in the 1840s are stamped “Kendall & Lawrence,” or “Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence.”

Born in Windsor, Vermont in 1807, Nicanor Kendall was the son of a local blacksmith. One day as a young man, he and his fiancée Laura Hubbard were enjoying a sleigh ride when Kendall spotted a squirrel in a tree. Deciding to impress his betrothed with a blasted rodent, Kendall retrieved his rifle from beneath his driver’s robe. In his haste, the flintlock’s hammer snagged on the blanket and the rifle suddenly discharged, injuring young Kendall’s hand and blasting a bullet through the top of his Laura’s hair. This frightening incident led Kendall to pursue a patent for a firelock in which the hammer was positioned beneath the frame, leaving the top of the gun unencumbered and reducing the chance the cocking spur might be accidentally snapped. Although several “underhammer” designs had already been patented, Kendall’s model was safer, and because it required fewer sophisticated parts, less expensive as well.

After serving an apprenticeship with renowned Windsor gunsmith Asa Story, Kendall began producing his patented firearms at a factory run by his father-in-law, Asahel Hubbard, the inventor of the rotating hydraulic pump. In order to cut down on labor costs, Hubbard’s pump factory was located inside the Vermont State Prison, where Hubbard paid the state for work done by its convicts. Kendall followed the same model, farming out unskilled labor to prisoners and reserving the more detailed work for his paid employees. Working in tandem with the simplicity of his design, this system allowed Kendall to manufacture inexpensive but reliable rifles—it also ensured a steady supply of workers who would never make demands or go on strike! Kendall’s first significant order came from Texas, which was gearing up for eventual war with Mexico and looking for a less costly alternative to the Springfield musket.

Eventually Asahel Hubbard sold the rights to his hydraulic pump and turned over the workshop entirely to his son-in-law. Hubbard moved to Davenport, Iowa, to work as a government surveyor. Kendall expanded his operations, producing his patented underhammer rifles and pistols, but also making shotguns and harmonica rifles. His firearms developed a reputation for elegance, featuring sleek lines, decorative brasswork, and stocks of curly maple. Engraving was common, some of it done by prison inmates. Indeed, the work of bank forger Christian Meadows became so well known, the governor of Vermont offered him a pardon, and Meadows spent the rest of his life working in Windsor as an engraver!

Nicanor Kendall’s workshop was also used to manufacture the designs of other inventors, such as the bizarre Bennett & Haviland Many-Chambered Revolving Rifle and the Whittier Revolving Rifle, which bears a striking relation to Kendall’s elegant firearms.

Robbins & Lawrence Company

In 1838, a young Army veteran and gunsmith named Robert Smith Lawrence came to work for Nicanor Kendall. Brilliant, energetic, and ambitious, Lawrence was appointed foreman of the prison workshop within six months. Soon, the two men became partners, and in 1843 they established a gun shop along Mill Brook in Windsor. The following year a retired lumber magnate named Samuel E. Robbins became a major investor, and in 1844 “Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence” was awarded a government contract for ten thousand U.S. Model 1841 percussion rifles. They immediately purchased additional land and began constructing a factory dedicated to the principle of interchangeable parts. Recruiting workers from Whitneyville and Springfield Armory, Robbins, Kendall & Lawrence developed new machines and techniques, successfully fulfilling the demanding contract and joining Eli Whitney and Simeon North at the vanguard of the modern firearms industry.

Feeling overwhelmed by the scope of this new operation, Nicanor Kendall sold his shares to Robert Lawrence and followed Laura’s father to Iowa, where he found work with the railroad. The spirit of invention remained in the family—Asahel Hubbard’s son Coleman became Secretary of Whitney Arms Company during the Civil War, and his nephew George Hubbard invented the coffee percolator in 1876.

Animated by the impressive energy of Robert S. Lawrence, the newly-reorganized “Robbins & Lawrence Company” soon emerged as one of the most advanced factories of the burgeoning American firearms industry. A cradle of innovation, some of the illustrious names connected to Robbins & Lawrence include Lewis Jennings, Benjamin Tyler Henry, Horace Smith, Daniel Wesson, and Christian Sharps. Even R&L’s eventual bankruptcy proved fertile, as Samuel Colt purchased their machines to improve the Springfield rifle, and Oliver Winchester picked up Benjamin Tyler Henry, who would go on to invent the Henry repeater. All of these historical relationships and connections are explored throughout the pages of the Deadlands Armory.

Robbins & Lawrence Company in Windsor, Vermont

Brunswick Rifle

1836–1885, UK, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .704 “belted,” Range 20/200/400, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d12, STR d6, Rare.

Intended to replace the Baker flintlock rifle, the first Brunswick rifle rolled from Enfield’s Royal Small Arms Factory in 1836, and passed through several iterations before being formally retired from production a half-century later. With its unique two-groove rifling, the Brunswick fired a special “belted” ball designed to snugly fit its twin spirals. Although these winged balls achieved more accurate results than standard rounds, they had to be oriented correctly before fitting into the muzzle, and required specialized bullet molds to manufacture. Tricky to load and easy to foul, the Brunswick was never as widely admired as the Baker, and eventually developed a reputation as being “difficult.” Nevertheless, over a thousand were sold to the Confederacy, and the Brunswick was the rifle of choice for the 26th Louisiana Infantry.

|

|

|

| Brunswick muzzle | Brunswick bullet mold | Brunswick “belted” ball |

U.S. Model 1841 Percussion Rifle, “Harpers Ferry Rifle,” “Mississippi Rifle”

1846–1861, USA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .54, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Rare. Notes: Despite being designed in 1841, the rifle was not put into mass production until 1846. Some Model 1841 rifles were later re-bored to accept the .58 Minié ball. These variants inflict DAM 1d10+1d12.

In 1842 Eli Whitney Blake, the nephew of Eli Whitney, was appointed head of Harpers Ferry Armory in Virginia. Charged with the development of the new U.S. Model 1841, Blake hired Thomas Warner of Springfield Armory as his foreman. A vigorous proponent of standardization, Warner had developed a reputation for bringing Springfield Armory up to the highest standards of precision. Blake and Warner brought the same attention to detail to Harpers Ferry, ensuring that firearms made from both Federal armories would possess interchangeable parts. During this time, Harpers Ferry produced the U.S. Model 1841 Percussion Rifle, the first percussion rifle to be adopted by the U.S. military.

Because rifles were considered more difficult to load and maintain than smoothbore muskets, they were issued only to specialized units. During the Mexican-American War, Colonel Jefferson Davis of Mississippi’s 155th Infantry Regiment requested that his men be armed with “Harpers Ferry” rifles, but his request was denied by General Winfield Scott. Appealing directly to President James K. Polk, the future President of the Confederacy was granted his wish, and his regiment was issued the new Model 1841. The 155th became known as the “Mississippi Rifles,” and won glory during the Battle of Buena Vista, where Jefferson Davis issued his famous command, “Stand fast, Mississippians!” Ever since then, the “Harpers Ferry” rifle has been better known as the “Mississippi Rifle.”

Widely considered to be an exceptionally handsome firearm, the Model 1841 has a lacquered stock of Pennsylvania-grown black walnut, sports all brass furnishings, and features a brass patchbox. Like most U.S. firearms, many private workshops also contracted to produce the pattern, including Eli Whitney of New Haven, E. Remington of New York, Robbins & Lawrence of Vermont, George W. Tyron of Philadelphia, and the Palmetto Armory of Columbia, South Carolina, who used equipment purchased from Tyron. In 1861, Colt purchased five thousand Model 1841 rifles, re-bored them to fit the contemporary .58 caliber round, and refitted them with Colt sights and Colt bayonets.

Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket

1853–1867, UK, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .577-68-530 Pritchett, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Common.

With the introduction of the Minié ball, rifles were finally made practical for the common soldier, and the Royal Small Arms Factory responded with the .705 caliber Pattern 1851 Rifle-Musket, the first Enfield rifle designed to accept the new type of round. This model was quickly supplanted by the smaller-caliber Pattern 1853 Enfield, one of the most successful rifles of the mid-century. Used to great effect during the Crimean War (1853–1856), the P53 Enfield was prized for its accuracy, its durability, and its comparatively light weight. Set with an adjustable rear ladder sight, the rifle has a 39” barrel, and fires a .577 “Pritchett” style Minié ball. Fortunately for shooters “across the pond,” the P53 also accepts the standard American .58 Minié-Burton round. Smuggled to the CSA in large numbers during the early 1860s and copied by many southern armories, Confederate use of the firearm was phased out after the Macon “Dixie” rolled out in 1867. In further tribute to its versatility, the Pattern 53 Enfield was the basis for the famous Snider-Enfield, originally a “conversion” that transformed the P53 into a breech-loaded rifle.

With the introduction of the Minié ball, rifles were finally made practical for the common soldier, and the Royal Small Arms Factory responded with the .705 caliber Pattern 1851 Rifle-Musket, the first Enfield rifle designed to accept the new type of round. This model was quickly supplanted by the smaller-caliber Pattern 1853 Enfield, one of the most successful rifles of the mid-century. Used to great effect during the Crimean War (1853–1856), the P53 Enfield was prized for its accuracy, its durability, and its comparatively light weight. Set with an adjustable rear ladder sight, the rifle has a 39” barrel, and fires a .577 “Pritchett” style Minié ball. Fortunately for shooters “across the pond,” the P53 also accepts the standard American .58 Minié-Burton round. Smuggled to the CSA in large numbers during the early 1860s and copied by many southern armories, Confederate use of the firearm was phased out after the Macon “Dixie” rolled out in 1867. In further tribute to its versatility, the Pattern 53 Enfield was the basis for the famous Snider-Enfield, originally a “conversion” that transformed the P53 into a breech-loaded rifle.

Windsor Enfield

During the height of the Crimean War, demands for the P53 became so intense that Great Britain licensed the pattern to the Robbins & Lawrence Company of Windsor, Vermont, an American armory with a solid reputation for mass-producing quality firearms. Unfortunately, the Crimean War ended halfway through their production run, and the Crown cancelled the contract, forcing R&L into bankruptcy. Anticipating a possible renewal of interest in the P53, Samuel Colt purchased the R&L equipment cheaply at auction. Meanwhile, many of the remaining “Windsor Enfields” found their way into American hands—particularly Southern American hands

Lorenz Rifle

1854–1860, Austria-Hungary, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .54, Range 40/400/800, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d10, STR d6, Uncommon. Note: These statistics are for the “medium range” Lorenz.

Designed in 1854 by Austrian lieutenant Joseph Lorenz, this rifle replaced the Augustin rifled musket of the previous generation. The sheer size of the Austro-Hungarian Empire necessitated a large number of firearms, and the Lorenz was mass-produced at numerous manufacturers over the course of the mid-1850s. As a result, the Lorenz suffered from a lack of quality control, with some rifles being more shoddily crafted than others. Nevertheless, the Lorenz slowly made its way into the hands of Austrian forces, and was produced in three variants—short, medium, and long-range. The primary difference between these models was the degree of “twist” to the rifling, with the long-range sharpshooter model having the most spirals.

Many Lorenz rifles made their way to America for the Civil War, with the Union placing an order for 230,000 and the Confederacy receiving around 100,000. Possessing the same uneven quality as they did in Europe, the rifles were either cherished or reviled, with those bearing the Vienna Arsenal stamp considered the most reliable. Some were re-bored to accept the .58 rounds more common to the Springfield or Enfield. Used all the way past the Siege of Vicksburg, the Lorenz was the third most common muzzle-loader of the Civil War.

This Lorenz was carved by a Civil War veteran

1867 Wänzl Rifle

Beginning in 1867, the Austrians began converting thousands of Lorenz rifles into breechloaders. Known as Wänzl rifles, they were chambered for the 14x33mm Wänzl rimfire cartridge.

Springfield U.S. Model 1855 Rifled Musket

1855–1860, USA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .58 Minié-Burton, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Uncommon. Notes: If using the Maynard tape primer system, the Rate of Fire is 1/3, but a roll of Natural 1 results in a misfire. Weighing nine pounds and sporting a 40” barrel, the Springfield Armory’s U.S. Model 1855 Rifled Musket was the first American firearm to effectively use the .58 caliber Minié-Burton ball. Adopted for official Army use by Mississippi Rifle enthusiast and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the Model 1855 proved itself far superior to the smoothbore muskets of the previous generation. Utilizing the unique “Maynard tape” system, a paper spool of percussion caps was automatically spring-fed into place when the hammer was cocked. Although this system was meant to accelerate the loading process, in actual practice, the tape grew damp, the caps misfired, and the spring mechanism malfunctioned. As a result, many soldiers opted to use percussion caps instead of the Maynard tape. The design was modified slightly in 1858, adding a patchbox to the buttstock for storing a greased cloth. A rear flip-up “leaf” style sight was added, and the brass nosepiece was replaced with iron.

Weighing nine pounds and sporting a 40” barrel, the Springfield Armory’s U.S. Model 1855 Rifled Musket was the first American firearm to effectively use the .58 caliber Minié-Burton ball. Adopted for official Army use by Mississippi Rifle enthusiast and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, the Model 1855 proved itself far superior to the smoothbore muskets of the previous generation. Utilizing the unique “Maynard tape” system, a paper spool of percussion caps was automatically spring-fed into place when the hammer was cocked. Although this system was meant to accelerate the loading process, in actual practice, the tape grew damp, the caps misfired, and the spring mechanism malfunctioned. As a result, many soldiers opted to use percussion caps instead of the Maynard tape. The design was modified slightly in 1858, adding a patchbox to the buttstock for storing a greased cloth. A rear flip-up “leaf” style sight was added, and the brass nosepiece was replaced with iron.

Despite the modern designation of “Springfield” in its name, the U.S. Model 1855 Rifled Musket was also produced at Harpers Ferry. Because thousands of Model 1855 rifles were stored in southern arsenals in 1861, it became a popular Confederate weapon during the first years of the Civil War. It also became the template for the future Richmond Armory rifles, produced on equipment salvaged from Harpers Ferry after the armory was abandoned by its Federal garrison on April 18, 1861.

Whitworth Rifle

1857–1865, UK, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .451 Whitworth, Range 90/900/1800, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 2d8, STR d6, Rare. Note: If the Shooter is using Whitworth hexagonal rounds, the range is increased to 100/1000/2000.

During the Crimean War, British engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth developed a new kind of hexagonal-bore rifling that proved effective in increasing the range and accuracy of brass howitzers. In 1857, Sir Joseph applied this technique to small arms and produced the world’s first genuine sniper rifle. Forty-nine inches in length and weighing over nine pounds, the Whitworth Rifle is capable of reaching an extreme range of 2000 yards, a significant improvement over the Pattern 1853 Enfield. Chambered for the smaller .451 round, to unlock the rifle’s true potential the shooter needs to employ hexagonally-shaped rounds designed to fit Whitworth’s rifling.

Easily fouled and expensive to produce, the Whitworth’s popularity was generally restricted to specialists and sharpshooters; but with one of Colonel Davison’s telescopic sights fixed to its left side, the Whitworth could be brutally effective. Sold to the Confederacy during the early days of the Civil War, the Whitworth was valued for its ability to pick off Federal officers and artillery crews. The Whitworth’s most famous victim was Union general John Sedgewick, who was sniped at the Battle of Spotsylvania from nearly 1000 yards away. Reputedly, Sedgewick’s last words were, “What? Men dodging this way for single bullets? I’m ashamed of you, dodging that way. They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance!”

Richmond Armory Rifles

1861–1865, CSA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .58 Minié-Burton, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Uncommon.

Richmond Armory 1861 Type I Rifled Musket.

Richmond Armory 1861 Type I Rifled Musket.

When Virginia seceded from the Union in April 1861, the Federal garrison stationed at Harpers Ferry attempted to burn the armory and destroy the equipment. Fortunately for the Confederacy, they were thwarted by locals sympathetic to secession, and much of the armory’s equipment was salvaged. Dispatched to Richmond during the first Confederate occupation, the equipment was used to produce Southern “copies” of the U.S. Model 1855 Rifled Musket. Because these were intended to be fitted with the Maynard tape priming system, their lockplates featured a distinctive “humpback” shape. This holdover distinguishes the early “Type I” Richmond rifles from the later “Type II” and “Type III” variants, which were made from original dies and more closely resemble the U.S. Model 1861 Springfield. Richmond Armory produced each of these three types in three variants, distinguished by the lengths of their barrels: a 25” carbine, a 30” artillery musketoon, and a standard 40” rifled infantry musket.

Richmond Armory 1865 Type III Rifled Musket

Historically, the Richmond Armory lasted until the end of the Civil War. In Deadlands 1876, the opening of the New Macon Armory at Griswoldville in 1866 signaled the beginning of a more robust Confederate arms program, and Richmond Armory was repurposed to produce firearms based on New Macon patterns such as the P67 Dixie and the P74 Manassas.

Fayetteville Armory

The Fayetteville Armory also received equipment from Harpers Ferry, and produced between eight to nine thousand rifles in North Carolina. These went through a similar production run, with each model from “Type I” to “Type IV” decreasing the size of “humpback” and aligning itself more closely with the U.S. Model 1861. Starting with the “Type III,” Fayetteville rifles sported distinctive S-shaped hammers.

Fayetteville Type III Rifled Musket

Fayetteville Type III Rifled Musket

Cook & Brother Rifle

1862–1864, CSA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .58, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Common.

In 1855, English expatriates Ferdinand W.C. Cook and his brother Francis L. Cook moved from New York to New Orleans. When the Civil War broke out, they began manufacturing high-quality rifles and carbines based on the Pattern 1853 Enfield, famously boasting “that rifles could be made here as well as in Yankee land or in Europe.” In 1862 Union encroachment necessitated a harried relocation to Athens, Georgia, where they continued to make infantry rifles, artillery musketoons, and cavalry carbines, now featuring a distinctive Confederate flag stamped on the lockplate. Generally considered one of the finest armories in the South, Cook & Brother produced nearly eight thousand superbly-crafted firearms for the Confederate cause.

With the threat of Sherman looming over Georgia, Ferdinand Cook helped organize his workers into the 23rd Georgia Local Defense Battalion, a volunteer militia dedicated to protecting Confederate arms production. On November 22, 1864, Major Ferdinand Cook and his battalion fought in the Battle of Griswoldville, after which they were sent to defend Hardeeville, South Carolina from Union attempts to cut the railroad from Charleston to Savannah. On December 11, Major Ferdinand Cook was shot and killed by a Federal sharpshooter, effectively ending the business of Cook & Brothers, which was seized by the Union after the War. In Deadlands 1876 the surviving brother, Captain Francis Cook, assisted in the rebuilding of Griswoldville and now serves as a director at the New Macon Armory.

Historical Confederate Armories & Deadlands 1876

During its short lifetime, the Richmond Armory produced more guns than all the other Confederate armories combined, with Fayetteville coming in second, and Cook & Brother earning top scores for quality. For Deadlands campaigns requiring additional detail and authenticity, the Marshal is invited to research Confederate firearms produced at state armories in Asheville, Columbus, Tallassee, Pulaski, and Grenville; as well as private gunsmiths such as Clapp, Gates & Company at the Cedar Hill Foundry in North Carolina; Dickson & Nelson in Adairsville, Georgia; H.C. Lamb in Jamestown, North Carolina; and Mendenhall, Jones & Gardner in North Carolina. Most produced copies of Springfield rifles or the British P53 Enfield, but some Confederate gunsmiths experimented with designs of their own, such as Jere Tarpley’s Breech-Loading Carbine or the Rising Breech Carbine produced by Bilharz, Hall & Company in Virginia. As usual, Flayderman’s Guide has all the relevant details.

Springfield Model 1861 Rifled Musket

1861–1872, USA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .58 Minié-Burton, Range 50/500/1000, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Very common. Note: The above statistics may also be used for the 1861 “Colt Special” and the later Model 1863 Springfield.

In 1861, the Springfield Armory replaced the expensive and unreliable Maynard tape system with a standard percussion lock, and the U.S. Model 1861 Rifled Musket was introduced to immediate acclaim. As the burgeoning Civil War and the destruction of Harpers Ferry Armory sharply increased the demand for new rifles, Springfield licensed its patent to several private contractors, including Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company, which had recently purchased the equipment Robbin & Lawrence had used to make the Pattern 1853 “Windsor” Enfield. Although Colt promised to faithfully reproduce the Springfield, he used the Enfield equipment to produce a hybrid model, using Enfield rifling and introducing some “improvements” to Springfield’s pattern by removing the bolster screw, retooling the gun bands, and adding the Enfield’s S-shaped hammer.

Detail of the “Colt Special,” based on the Pattern 1853 Enfield.

Detail of the “Colt Special,” based on the Pattern 1853 Enfield.

Although the U.S. government was initially furious at Colt, he argued that his “minor” improvements resulted in a superior rifle. Given their desperate need for new firearms, the Army honored the contract, and the “Colt Special” proved to be quite popular. Indeed, after Samuel Colt died in 1862, they grudgingly honored him by incorporating some of his changes into the U.S. Model 1863, the last muzzle-loader to be produced at the Springfield Armory. The most commonly-used rifle of the early Civil War, many muzzle-loaded Springfield rifles were later converted to breech-loading “Trapdoor Springfields.”

Remington Model 1863 Percussion Contract Rifle, “Zouave”

1863–1865, USA, muzzle-loaded caplock. Caliber .58 Minié-Burton, Range 60/600/1200, Capacity 1, Rate of Fire 1/5, DAM 1d10+1d12, STR d6, Rare. Note: The 1868 rolling-block conversion is Caliber .58 centerfire. In the years before the Civil War, E. Remington & Sons of Ilion, New York had developed a pretty solid reputation producing contract Model 1841 “Mississippi” rifles for the U.S. Government. When it came time to deliver another batch in 1863, Remington found themselves coming up short. Turning a problem into an opportunity, Remington offered to lower their prices if the U.S. Government would award them a new contract for 40,000 Model 1861 rifles. Uncle Sam agreed, and Remington completed the last of the Mississippi rifles in January 1864. However, much as Colt did with the Model 1861, Remington took the liberty of “improving” the aging pattern, making the hammer more responsive, case-hardening the lock, and adding brass furnishings. Handsome, accurate, and reliable, today the “Model 1863” is widely considered to be one the finest muzzle-loaders of the era. It is also one of the last.

In the years before the Civil War, E. Remington & Sons of Ilion, New York had developed a pretty solid reputation producing contract Model 1841 “Mississippi” rifles for the U.S. Government. When it came time to deliver another batch in 1863, Remington found themselves coming up short. Turning a problem into an opportunity, Remington offered to lower their prices if the U.S. Government would award them a new contract for 40,000 Model 1861 rifles. Uncle Sam agreed, and Remington completed the last of the Mississippi rifles in January 1864. However, much as Colt did with the Model 1861, Remington took the liberty of “improving” the aging pattern, making the hammer more responsive, case-hardening the lock, and adding brass furnishings. Handsome, accurate, and reliable, today the “Model 1863” is widely considered to be one the finest muzzle-loaders of the era. It is also one of the last.

Historically, the Model 1863 rifles came too late in the War to have any impact, and there is no evidence they were ever used. Known to collectors as “Zouave” rifles, the origin of the name is debated—some believe it’s on account of their flashy appearance; others contend they were actually issued to a company of New York Zouaves. In the fictional milieu of Deadlands 1876, the Model 1863 was indeed issued, and quickly became the favorite of the Zouave and Chasseur regiments of New York and Pennsylvania. Many of these muzzle-loaded rifles were later converted to rolling-blocks, which the new Remington Model 1877 “Centennial Gotham” will shortly replace.

This modern reproduction was made by Miroku Firearms of Japan, but represents a fine Deadlands Zouave rifle as customized for Colonel Edward Brush Fowler of the 14th Regiment New York State Militia, the famous “Brooklyn Chasseurs.”

<< Rules | Innovations | Breech | Revolving | Repeaters | Bolt-Action >>

Sources & Notes

Books

To create this resource, I leaned heavily on Norm Flayderman’s Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms. Featuring photographs and detailed descriptions of thousands of antique firearms, this is an essential resource for any historical gaming campaign, and Flayderman’s Guide introduced me to several of the more bizarre weapons described in the Deadlands Armory. To flesh out some of the statistical details, I turned to John Walter’s Rifles of the World. I also recommend Dennis Adler’s Guns of the American West and David Miller’s Illustrated Book of Guns. Both feature historical notes and full-color illustrations of the West’s most iconic firearms, many of which are museum pieces photographed especially for these books.

Internet

Of course, the Internet was crucial for my research. The Web is filled with antique firearm collectors, and much of the information in the Armory was gathered from gun-ownership forums, antique auction sites, and the homepages of Civil War reenactors. Anyone interested in the historical firearms described in the Armory can find a wealth of additional information online, including videos of many of these guns being loaded and fired—sometimes by authentically-costumed reenactors! But without a doubt, the most useful resource on obscure firearms is Ian McCollum’s Forgotten Weapons. Perpetually cheerful and possessing a dry sense of humor, McCollum works in conjunction with auction houses to produce short videos spotlighting authentic antique firearms. McCollum explains their history, carefully reveals their inner workings, and sometimes takes them to the firing range. I also relied on Wikipedia, Antique Arms, and the Firearms History, Technology & Development blog.

Image Credits

Many of the photographs of firearms used in the Armory have been “borrowed” from online sources. Because most owners of vintage firearms are good-natured folk with a passion for promoting their hobby, I have no doubt they’ll be happy to see their photographs used to promote a wider understanding of antique weaponry. Having said that, if anyone is offended that I’m using an image without proper authorization, please contact me and I’ll remove it immediately. Many photographs depict modern reproductions, usually manufactured by Uberti, Pietta, Pedersoli, Cimarron, Taylor’s, or Dixie Gun Works. I favor these photographs because they make the gun look contemporary, something a Deadlands character might purchase in a gun store or pry from the cold, dead fingers of his enemy. When I could not find a shiny new replica, I usually turned to vintage gun auctions. The four best resources for detailed images of antique firearms are the Rock Island Auction Company, James D. Julia Auctioneers, College Hill Arsenal, and the Collectors Archives from Collectors Firearms, Inc. Thank you!

Specific Online Sources

The following sites were invaluable in creating this resource: Joseph G. Bilby’s The Brown Bess Musket for Warfare History Network, The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop, the article on the Whitney Kennedy Large Frame Lever Action Rifle at Antique Arms, the appropriately-named Matthew Sharpe’s “Nock’s Volley Gun” for American Rifleman, Chris Eger’s piece on the Nock gun for Guns.com, which also features videos of the gun being fired, the Springfield Armory Museum for the Ellis-Jennings Repeating Flintlock, Harry Ridgeway’s collection of percussion caps, Craig L. Barry and Curt-Heinrich Schmidt’s U.S. Percussion Rifle, Model 1841 for “Wearing of the Gray,” the Civil War Arsenals page on the Maynard Tape system, Eric Ortner’s piece on the Maynard tape system originally appearing in the Civil War Courier, a fine Guns.com article on the Whitworth sniper rifle, another page on the Whitworth from The Long Roll and the Lost Cause blog, White Muzzleloading’s page on the P53 Enfield, the College Hill Arsenal’s informative page on Cook & Brother, and Curt Heinrich-Schmidt’s history of the somewhat-mysterious Remington Model 1863 Zouave for Civil War Reenactors Forum.

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 12 August 2023

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

PDF Version: Deadlands Armory – Rifles 1. Muzzle-Loaders