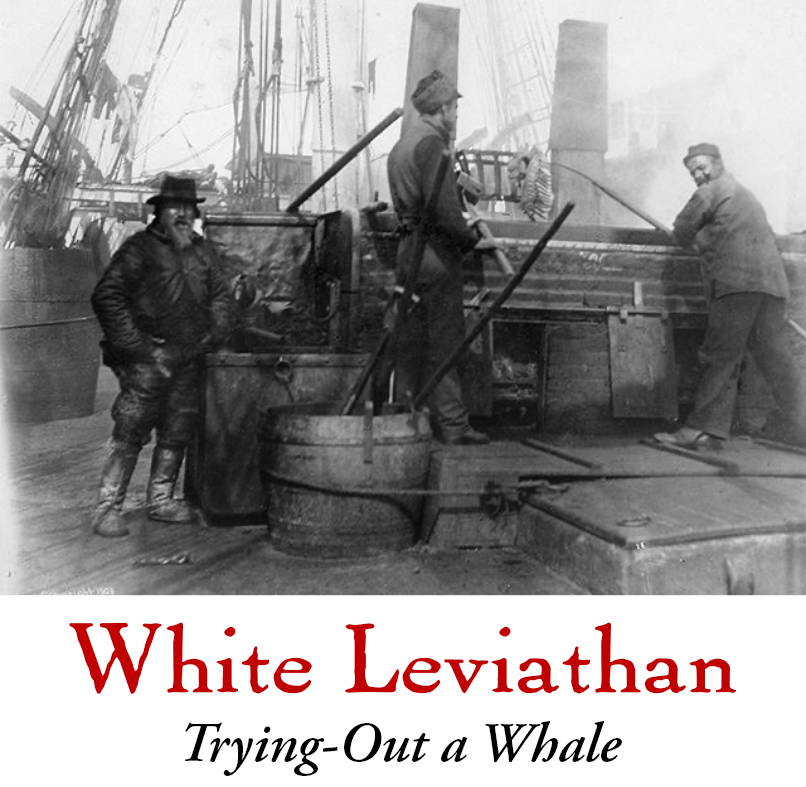

Trying-Out a Whale

- At September 17, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Call of Cthulhu

0

0

The ivory Pequod was turned into what seemed a shamble; every sailor a butcher. You would have thought we were offering up ten thousand red oxen to the sea gods…The heavers forward now resume their song, and while the one tackle is peeling and hoisting a second strip from the whale, the other is slowly slackened away, and down goes the first strip through the main hatchway right beneath, into an unfurnished parlor called the blubber-room. Into this twilight apartment sundry nimble hands keep coiling away the long blanket-piece as if it were a great live mass of plaited serpents. And thus the work proceeds; the two tackles hoisting and lowering simultaneously; both whale and windlass heaving, the heavers singing, the blubber-room gentlemen coiling, the mates scarfing, the ship straining, and all hands swearing occasionally, by way of assuaging the general friction.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, Chapter 67

Introduction

The process of cutting-in and trying-out a whale is the elaborate system in which the blubber of a whale is stripped and rendered into precious oil. It can take three days to process a large whale, during which time the crew works in six-hour “try-watches” around the clock, taking their meals on the fly and sleeping in filth-encrusted clothing. Commonly known as “boiling,” this work transforms the ship into a slaughterhouse: blood and oil cover the decks, greasy smoke churns from the try-pots, and the blubber room is crammed with oozing strips of flesh.

Blubber

Despite what lubbers imagine when they hear the word “blubber,” a whale’s blubber is neither soft nor gelatinous. Encasing the whale like a thick rind, blubber is compact, tough, and rubbery; 8-15” inches thick and oozing with oil. It’s protected by a patina of black skin, so thin it can be scraped off with a fingernail. Notwithstanding its toughness, blubber is easily separated from the body—not unlike the skin of an orange.

Roleplaying the Butchery

The first time the player characters hunt, kill, and butcher a whale should be a grand, roleplaying set-piece, with the Keeper sparing no gory detail. Greenhorns are often shocked by the brutality and sheer scale of the process, even those accustomed to butchering farm animals. The Keeper is welcome to call for Sanity rolls along the way, usually for a 0/1 loss.

Becoming Routine

Trying-out a whale is a remarkable process; but it becomes routine during the course of a three-year voyage. After all, a whaleship is basically a floating abattoir, and its workers quickly acclimatize to their roles as nautical butchers. By the time the player characters are onto their third or fourth whale, they’ll have become hardened killers, and there’s no need for greenhorn Sanity checks. Indeed, experienced hands learn to appreciate the trying-out in all its terrible glory—after all, each captured whale makes the voyage more profitable and brings them that much closer to home. After the first whale is tried-out, subsequent whales may be butchered with less attention to roleplaying the details, until eventually a whole month may be passed with, “You captured seven whales over the last few weeks—well done!” Of course, a few “Cutting-In Incidents” may keep the players on their toes, especially during rough seas.

Cutting-In & Trying-Out

The following outline describes the stages in rendering a dead whale to precious oil. For details on hunting and killing whales, see “Hunting Whales.”

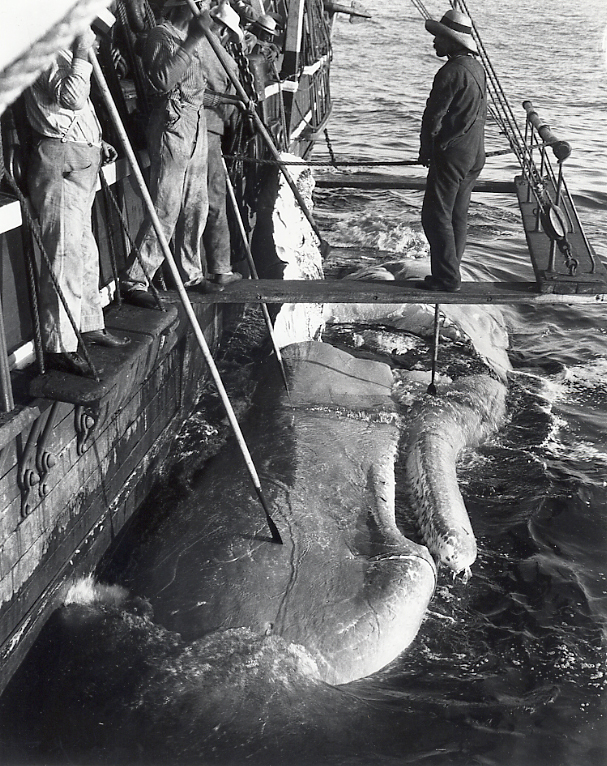

1. Securing the Whale

After a slain whale is towed back to the ship, its carcass is secured to the starboard flank. This is done by passing heavy chains around its flukes and hoisting the whale against the side, with the head pointing aft to reduce forward drag. If possible, the ship’s larboard side is turned leeward so the extra pressure on the sails counteracts the mass of the whale.

Next, the ship’s “cutting-stage” is lowered over the whale. Composed of three wide planks like the perimeter of a rectangle missing a side, the Quiddity’s cutting-stage also contains a small rail. The cutting-stage allows the men to get close to the whale and begin the process of stripping its blubber. Because the platform becomes slippery, the men are secured to the rails by “monkey ropes” tied to their waists.

From this point on, the bloody carcass begins to attract sharks. These voracious scavengers are the main reason a whale is tried-out as fast as possible, day or night—if not, there’d be little left to boil! In shark-infested waters, the sea below the cutting-stage churns with sharks, and the danger to workers on the platform is quite real. They are protected by sailors armed with 15-20’ spades, who to keep overly-ambitious sharks at bay with sharp, sudden jabs.

2. Removing the Blubber

In order to remove the blubber, the ship’s cutting tackle comes into play. A 150-pound “blubber hook” is fixed to a block-and-tackle system fastened to the lower masthead and connected to the windlass by a series of ropes and pulleys. (The blocks of the cutting tackles are customarily painted green.) A man, often a harpooneer, is attached to a monkey rope and lowered onto the body of the whale. He uses a spade to hack a hole into the whale’s blubber just between the eye and the flipper. The blubber hook is lowered down, and the harpooneer slips the hook through the hole and secures it fast. (If the seas are rough, this job may take several attempts—quite a nerve-wracking proposition if there’s sharks snapping at the man dangling above them! An Operate Heavy Machinery roll may be required.)

Once the blubber is hooked, a mate on the cutting stage begins hacking into the whale with a spade, outlining a 3-5 foot wide strip. By the efforts of twelve crewmen sweating at the windlass, the blubber hook is raised, perhaps to the sound of a capstan shanty. This first strip is often difficult to wrench free, and the ship may lean over, groaning in protest. But with a great snapping sound, the strip of blubber tears from the whale, the ship lurches back into position, and the first “blanket piece” is raised. From here on the work is much easier, and the blubber parts willingly, needing only a few custodial chops from the spademan to keep it peeling along the “scarf” as the whale rolls ponderously below.

By the time the blanket reaches the top of the tackle, it’s about 15-20 feet long, 3-5 feet wide, and weighs over a ton. A another hole is cut near the bottom, and a second blubber hook is inserted. A harpooneer then uses the long, sharp “boarding sword” to sever the strip above the second hook, which takes up the duty of peeling the whale. By this manner (as Melville states, “precisely as an orange is sometimes stripped by spiralizing it”), the whale is flensed in one continual strip, with the carcass of the whale rolling below and flooding the sea with blood and oil.

When the last strip of blubber has been removed, the mates cry “Five and forty more!” meaning 45 more barrels of oil. This traditional call is given no matter the size of the whale. Often it’s followed by “All hands aft to splice the main-brace,” which signals a break after the cutting-in, allowing the men to receive a tot of rum before the boiling begins.

3. The Blubber Room

Guided by men with gaffs, the blanket piece is lowered through the hatch and coiled on the floor of the blubber room. It’s reduced to smaller pieces by half-naked men, often crawling on their hands and knees. The men work in pairs: a pike-and-gaff man and a spademan. The gaff man hooks onto the blubber to prevent it from sliding on the oily, blood-soaked floor, while his partner climbs atop the blanket, chopping it into smaller “horse pieces” with his spade. As Melville writes, “If he cuts off one of his own toes, or one of his assistants’, would you be very much astonished?” Because blubber is so resilient, spades must be constantly sharpened and re-sharpened. This work is usually done by the blacksmith, “humping away” at his grindstone.

4. Mincing

The average size of a horse-piece is 3-4 feet long and 6-8 inches wide. These are transported back on deck, where a crewman uses a two-handled “chopping blade” to mince them into thin squares connected to each other by a spine. These pieces are called “books,” and the individual squares “Bible-leaves.” The goal is to mince the leaves as thinly as possible, which allows them to be rendered more quickly. Positioned by a wooden horse braced against the bulwarks, the worker drops his books into a tub, from whence they’re carried to the tryworks and forked into the trypots.

Pieces of blubber that resist mincing or have abnormal bits of whale flesh stuck to them are called “fat lean,” and are dumped in a barrel. After a few days broiling in the sun, these slimy chunks of “stink” are sorted by hand. Those which have loosened up are dispatched to the trypots. Pieces deemed beyond redemption are tossed to the sharks. Needless to say, this is a most unpleasant task, as the decaying flesh is putrid and gives off a terrible stench.

The Grandissimus

The Quiddity takes part in an unusual tradition, one that is not shared by all whalers. After the first bull is captured, the mincer and two associates sever and flay its penis. This loose skin is turned inside out, stretched, and left in the rigging to dry. Once it’s ready, a few deft cuts transform the casing into a sleeveless cassock, worn by the mincer as he performs his duties.

5. The Tryworks

The tryworks are where slabs of whale blubber are rendered into oil. The Quiddity’s tryworks consist of two 250-gallon iron cauldrons nestled in a brick kiln. Using kindling, a fire is lit beneath them, a fire which will subsequently be maintained by feeding it “cracklings,” or used-up scraps of blubber. The firebox is separated from the deck by a brick reservoir called a “duck pen.” This protects the wooden deck from the intense heat. Two copper cooling tanks are located on either side of the kiln. Starting up and directing the tryworks is the job of the second mate, and the harpooneers usually take shifts rendering the blubber. It takes about an hour to prepare one pot of oil.

The Cooling Process

Each trypot yields four barrels of oil. When ready, this tried-out oil is poured into a cooling tank, and fresh blubber is forked into the pot. Sailors often drop by to refill their lanterns or fry biscuits in the cooling oil. After the oil has reached a more reasonable temperature, it’s decanted into six-barrel casks. These are secured to the ship’s lashrails for a few additional days of cooling and maintenance. This calls for tireless attention from the cooper, who must monitor the contraction of the barrel’s staves and hoops and prevent leaking. Indeed, every sailor is expected to assist in this duty, “for now, ex officio, every sailor is a cooper.” After the casks have finished cooling, they’re lowered into the hold for storage. Once the whale has been boiled, the trypots are soapstoned and scoured with lye until bright and shining clean, then covered with wooden tops.

Operating the Tryworks

The first time a greenhorn mans the tryworks calls for a Whalecraft roll, with a failure earning a hot splash of oil for 1D4 HP damage. This roll is repeated until the sailor is successful, or the Keeper decides to punish the hapless fellow with a “Trying-Out Incident.” Once a seaman has become accustomed to the tryworks, Whalecraft rolls are only required for adverse conditions such as rough seas or sudden changes in weather. Failures may trigger a random “Trying-Out Incident.”

South Sea Whalers Boiling Blubber by Oswald Brierly (1876)

South Sea Whalers Boiling Blubber by Oswald Brierly (1876)

Hellship

Operating continually for three days and nights, the tryworks transform a whaler into a lurid hellscape. The glow from the fire illuminates the sails with flickering orange light, sparks must be constantly attended, and the men are covered with filth. The stench is indescribably awful, and the oily, black smoke covers everything with a greasy miasma. Melville’s description from Chapter 96 of Moby-Dick is essential reading for Keepers:

By midnight the works were in full operation. We were clear from the carcase; sail had been made; the wind was freshening; the wild ocean darkness was intense. But that darkness was licked up by the fierce flames, which at intervals forked forth from the sooty flues, and illuminated every lofty rope in the rigging, as with the famed Greek fire. The burning ship drove on, as if remorselessly commissioned to some vengeful deed… The hatch, removed from the top of the works, now afforded a wide hearth in front of them. Standing on this were the Tartarean shapes of the pagan harpooneers, always the whale-ship’s stokers. With huge pronged poles they pitched hissing masses of blubber into the scalding pots, or stirred up the fires beneath, till the snaky flames darted, curling, out of the doors to catch them by the feet. The smoke rolled away in sullen heaps. To every pitch of the ship there was a pitch of the boiling oil, which seemed all eagerness to leap into their faces. Opposite the mouth of the works, on the further side of the wide wooden hearth, was the windlass. This served for a sea-sofa. Here lounged the watch, when not otherwise employed, looking into the red heat of the fire, till their eyes felt scorched in their heads. Their tawny features, now all begrimed with smoke and sweat, their matted beards, and the contrasting barbaric brilliancy of their teeth, all these were strangely revealed in the capricious emblazonings of the works. As they narrated to each other their unholy adventures, their tales of terror told in words of mirth; as their uncivilized laughter forked upwards out of them, like the flames from the furnace; as to and fro, in their front, the harpooneers wildly gesticulated with their huge pronged forks and dippers; as the wind howled on, and the sea leaped, and the ship groaned and dived, and yet steadfastly shot her red hell further and further into the blackness of the sea and the night, and scornfully champed the white bone in her mouth, and viciously spat round her on all sides; then the rushing Pequod, freighted with savages, and laden with fire, and burning a corpse, and plunging into that blackness of darkness, seemed the material counterpart of her monomaniac commander’s soul.

6. The Remains of the Whale

Searching for Ambergris

As the flensing proceeds, a mate may probe the whale’s intestines for ambergris. It’s fairly rare, and only appears in sick whales. (See “Sperm Whale” for details.)

The Jaw

After the blubber has been stripped from the whale, the whale is rolled on his back and the jaw pried open. Its lips and tongue are removed for trying-out. Gripped tightly in a noose of chains from the cutting-tackle, the jaw is pulled up, and the mates use their long spades to peel back the muscle and sever the jaw from the skull. The jaw is brought on deck and cleaned, then allowed to rot just long enough to loosen the teeth. The teeth and bone of sperm whales are valuable for scrimshaw and for fashioning various useful implements, including peg-legs for dismasted captains.

Severing the Head

After the jaw has been removed, the whale must be decapitated. The mates sever the vertebrae with their cruel spades and hack off its head, allowing the flensed carcass to sink into the sharky depths. (The British call this useless remainder the “kreng.”) The head, which weighs between 12-17 tons, is secured at the stern of the ship. When the crew is ready, it’s hoisted up by the gangway for further processing. The “junk” is removed and tried-out separately from the body blubber. (See “Sperm Whale” for details.)

7. Bailing the Case

The final step in butchering the whale is to bail the case—the reservoir of spermaceti located in the whale’s prodigious forehead. The head is hoisted up to the gangway, and a mate or harpooner uses spades to “find the case” while trying not to spill any precious spermaceti. The case is then bailed, or scooped clean with conical buckets. (It’s not unknown for mates to order smaller seamen to go inside the case for this work!) The average case can hold up to 500 gallons of spermaceti oil. Spermaceti is aromatic and clear, but begins to solidify upon contact with the cooler air. So that it doesn’t clump before trying-out, a group of crewman are often recruited to hand-squeeze the oil in tubs. (Chapter 94 of Moby-Dick is quite famous for its generous description of this brotherly process.) Because spermaceti melts easily, it takes only a moment in the trypots, and is stored in special casks. Strangely enough, some men enjoy bailing the case, as spermaceti oil is considered quite pleasant to touch, and brings some relief from harsh weather conditions!

8. Stowing Down and Cleaning Up

After the whale has been exhaustively tried-out, the ship is vigorously cleaned from top to bottom. Whale-parts are jettisoned, the rigging and decks are scrubbed of soot, the cooled casks are stored below, the try-pots are scoured with soapstone and lye, equipment is sharpened, cleaned, and stowed, and the blubber room is washed to the best of the sailors’ ability. The whale himself lends to this process: the edges of his flukes are cut into “lippers” used to squeegee the decks, spermaceti oil is used as a cleaning agent, and lye made from his burned ashes scours the filth of his passing.

Sources and Notes

While this piece drew on many helpful resources, including Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, the best nonfiction book about the ins-and-outs of whaling remains Clifford W. Ashley’s The Yankee Whaler. And special thanks to Eric Jay Dolin for unearthing the amazing example of nineteenth-century writing that follows these acknowledgements!

Images

All of the photographs used in this section are from the famous book, Cutting In a Whale: A Series of Twenty-Five Photographs. Published in 1903 by H.S. Hutchinson & Company, these photos are among the most authentic—and gruesome!—records of the trade. They were taken onboard the whaler California while operating along the Japan Ground. The painting South Sea Whalers Boiling Blubber is by the incomparable Oswald Brierly (1817–1894).

To turn out at midnight & put on clothes soaked in oil—to go on deck & work for Eighteen hours among blubber—slipping—& stumbling on the sloppy decks—till you are covered from crown to heel with oil…to dream you are under piles of blubber that are heaping & falling upon you till you wake up with a suffocating sense of fear & agony… to be weary—dirty—oily—sleepy—sick—disgusted with yourself & everybody & everything…to go through such a scene, I confess the very thought turns my stomach.

—William A. Abbe, Logbook of the Atkins Adams, 17 July 1869

White Leviathan > The Quiddity and Whaling

[Back to Hunting Whales | White Leviathan TOC | Forward to Quiddity Random Tables]

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 27 August 2023

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

White Leviathan PDF: [TBD]