Period & Setting: 1844-1846

- At August 22, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Call of Cthulhu

0

0

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

—William Faulkner, “Requiem for a Nun”

Introduction

This section offers a glimpse into the history, politics, art, culture, and religion of the mid-nineteenth century. It may be photocopied as a handout, or placed online for player access. Because it’s intended as a resource, it’s chock-full of useful links for gamers who’d like to explore the period further.

Cthulhu by Lamplight

White Leviathan takes place from 1844 to 1846, a period of time that falls squarely in the Victorian era, a familiar setting to enthusiasts of horror and the supernatural. When most gamers imagine a Victorian milieu, they think of Jack the Ripper, Sherlock Holmes, and Dracula. They think of Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Oscar Wilde. The period has been immortalized in countless movies and television shows, from Terror In the Wax Museum to Penny Dreadful. It’s been adapted into steampunk, and explored in roleplaying games like Space 1889 and Deadlands. Chaosium itself has published several Victorian supplements, including Cthulhu by Gaslight, Dark Designs, and Sacraments of Evil.

Well, the Keeper needs to forget all that—or at least, most of it! Everything mentioned above belongs to the late Victorian period. White Leviathan takes place during the time of Edgar Allan Poe and the Brontë sisters: one generation before Captain Nemo launches the Nautilus, two generations before Dr. Jekyll becomes Mr. Hyde, and three generations before Martian tripods stride across Woking. In 1844, Charles Dickens has already haunted Scrooge with the specter of Jacob Marley, but the Brontë sisters won’t summon the ghosts of Wuthering Heights and Thornfield Hall for another three years. Poe’s House of Usher has already fallen, but Hawthorne’s House of the Seven Gables looms just over the horizon.

The 1840s are a decade still shaking off the eighteenth century, and many familiar Victorian tropes do not apply to White Leviathan. Popular photography, electric lighting, the phonograph; all these innovations are years in the future. In 1844, railroads have only begun connecting the cities of the East Coast, and gaslighting and telegraphy are cutting-edge technologies. Indoor plumbing is a luxury. Most ships are powered by sail, more people travel by carriage than locomotive, and the galvanic battery and hydrogen balloon are marvels inspiring early works of science fiction—an unnamed genre still in its infancy. In 1844, the surgical needle has just been invented, the daguerreotype is five years old, and the Colt revolver is a new-fangled oddity. People who can’t afford a cap-and-ball rifle make do with their father’s flintlock. Petroleum has yet to be discovered, hence the international need for whale oil, which lubricates the gears and clockwork of the burgeoning industrial revolution. Whale oil illuminates mid-century darkness, and is used in lamps, candles, lighthouses, and magic lantern shows.

Politics

The campaign begins on October 27, 1844. America’s most recent armed conflict was the lengthy Second Seminole War, fought in Florida between 1835-1842. Many Americans bitterly recall the War of 1812; and the oldest dimly remember the Revolution. Everyone’s grandparents remember George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. In 1844, Abraham Lincoln is a successful lawyer who’s just served three terms in the Illinois House of Representatives. (He’ll be elected freshman Congressman in 1846.)

Slavery remains a terrible reality for many Americans, and the Civil War is a generation away. It is illegal to import slaves into the United States, but Americans born into slavery may still be bought and sold. Baltimore has emerged as a major hub for slave trading, its ships dispatching thousands of enslaved people to the markets of New Orleans and the deep South. Whether to allow slavery in new territories and states is a fractious issue; and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 remains hotly debated. Both sides are entrenching more deeply in their positions, the Democrats generally supporting the spread of slavery and the Whigs generally opposed. Although John C. Calhoun continues to lift his formidable voice in support of the “peculiar institution,” the abolition movement is gaining steam. William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass are household names, and anti-slavery societies have sprung up across the east, many supported by Protestant religious movements. Nat Turner’s slave rebellion occurred in 1831, over a decade ago; but its aftershocks are still being measured by slaveholders and abolitionists alike. The recent Amistad and Creole rebellions have further intensified the issue.

Recent newsworthy events include the Panic of 1837, which touched off a depression that lasted until 1843, the forcible opening of China for trade, and whether or not the recently-declared Republic of Texas should be annexed to the United States. This latter issue will trigger America’s next war.

The 1844 Election

The year 1844 is an election year, and an unusual one at that. The current President is John Tyler, who was sworn into office after William Henry Harrison died one month into his term. An unpopular president, Tyler was dubbed “His Accidency” by his own party, who were affronted by his pro-slavery positions and his refusal to enact Whig policies. The majority of Tyler’s cabinet resigned, the Whigs expelled him from the party, and he came close to impeachment. In modern terms, the Whigs “primaried” Tyler, and are running the popular Henry Clay against Democratic candidate James K. Polk of Tennessee. A virtual unknown, Polk has capitalized on America’s hunger for expansion and has been conducting a belligerent campaign bolstered by strong nationalist sentiments. A few weeks after White Leviathan begins, Clay loses the election to Polk, “Napoleon of the Stump,” returning the party of Andrew Jackson to power. Within a decade, the Whigs would collapse entirely. Many northern Whigs allied with Free-Soilers to establish the Republican Party, while southern Whigs joined the “Know Nothings” to form the nativist American Party.

The Polk Presidency

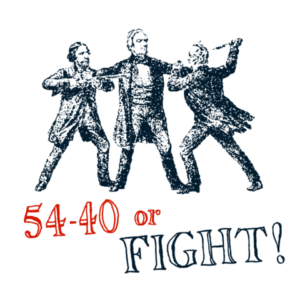

While American politics are not the primary focus of White Leviathan, most of the campaign unfolds under the Polk Presidency, a period marked by aggressive expansionism. Indeed, the industry of whaling and the opening of the Pacific are part and parcel with this period of American imperialism, so a few words may help set the stage. An unwavering disciple of manifest destiny, President Polk oversaw a term that resulted in significant territorial acquisitions. Florida entered the Union on March 3, 1845, and Texas was annexed on December 29, 1845, bringing the number of states to 28. “Young Hickory” also set his sights on the Oregon Country, a massive territory “shared” between the U.S. and Great Britain since 1818. As Oregon Fever propelled increasingly more Americans westward, Polk began a dangerous game of chicken with the British over the partitioning of this disputed land. British hawks wanted control of the territory down to the 42nd parallel, while their Yankee counterparts demanded possession all the way up to Russian Alaska, hence the Democrat’s bellicose slogan, “54°40’ or Fight!”

After a tense period of brinksmanship and saber rattling, Polk narrowly avoided war, and negotiations with Britain in 1846 established the familiar border at the 49th parallel. That same year, Polk launched the Mexican-American War, a shockingly successful adventure that resulted in the 1848 acquisition of present-day California and most of the American Southwest.

After a tense period of brinksmanship and saber rattling, Polk narrowly avoided war, and negotiations with Britain in 1846 established the familiar border at the 49th parallel. That same year, Polk launched the Mexican-American War, a shockingly successful adventure that resulted in the 1848 acquisition of present-day California and most of the American Southwest.

The United States was finally in a position to realize its dream of being a continental empire, with Pacific ports ready to capitalize on the markets of China and Japan. For generations Americans had looked backwards, across the Atlantic to Europe; suddenly the Pacific assumed its rightful place as an American frontier, every bit as exciting as the Wild West. This cultural “construction” of the Pacific became a powerful center of intellectual gravity, igniting a constellation of romantic associations, shaping the fiction of Herman Melville, and attracting the American imagination from Moby-Dick to South Pacific—not to mention H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu!”

International Politics

Internationally, mid-nineteenth century Europe is still reeling from the Napoleonic Wars. Revolution is spreading through Europe like a slow, inexorable fire, fueled by liberal political principles and rekindled feelings of nationalism. Britain remains a powerful bulwark against anti-monarchial sentiment, and has just won the controversial “Opium War” with China. The conflict revealed unexpected weaknesses in the Qing Empire, placed Hong Kong under British control in 1842, and opened China to more aggressive trading policies. Elsewhere the fleets of Britain, the United States, and Europe compete for trade throughout India and Asia, while the Ottoman Empire staves off decline through intense programs of modernization throughout Turkey. Japan is in the final years of the Tokugawa Shogunate, a decade away from ending centuries of rigid isolationism. Meanwhile in Paris, Karl Marx has just met Friedrich Engels, who showed the radical young editor his manuscript of The Condition of the Working Class in England. The Communist Manifesto is right around the corner.

Religion

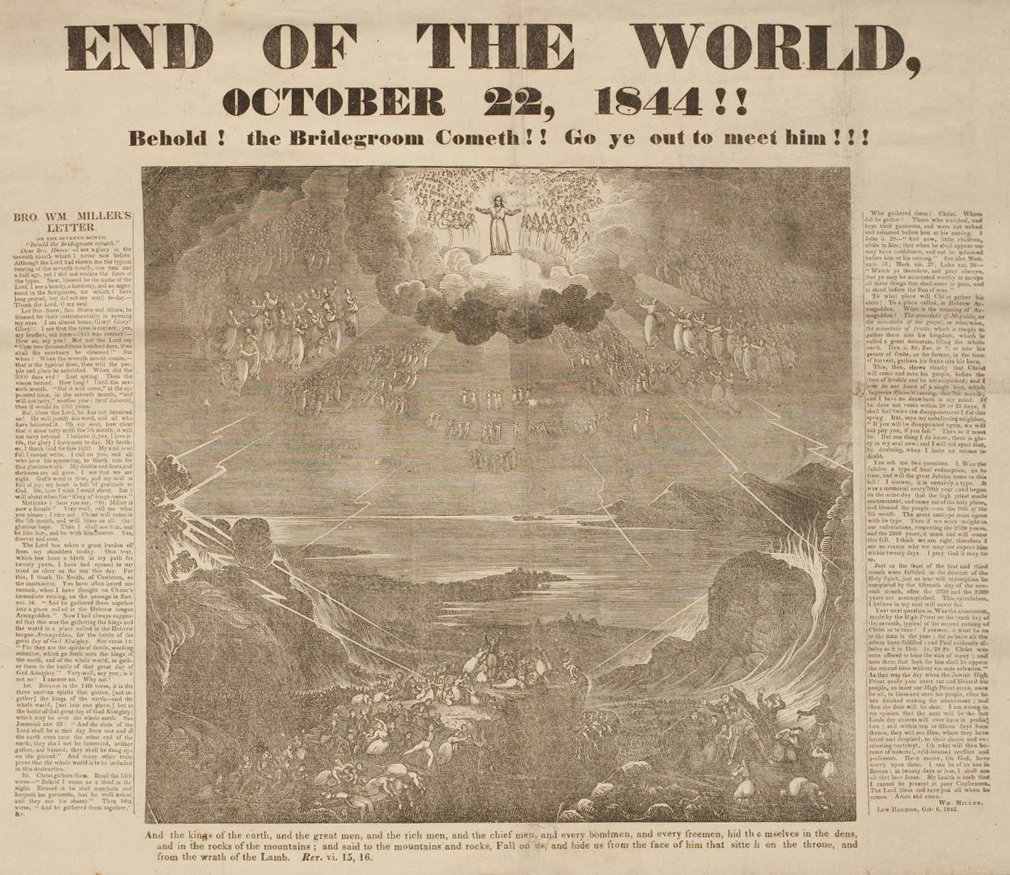

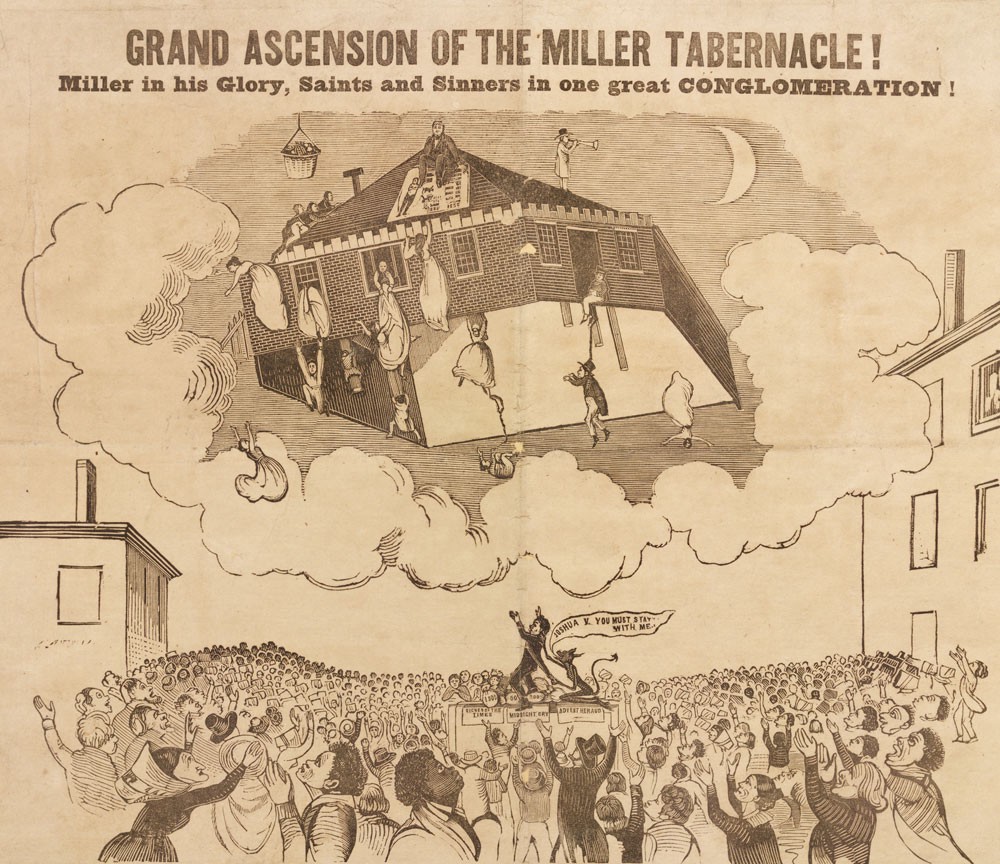

In 1844 America is at the tail end of the Second Great Awakening, a fifty-year period of Protestant revivalism that spawned dozens of religious movements in New York, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Tennessee. So many of these fiery movements emerged from upstate New York it would soon be nicknamed the “Burned-over district.” The two with the most lasting impact are Mormonism and Millerism, both of which recognize 1844 as a watershed year.

On June 27, 1844, Mormon founder Joseph Smith, Jr. was martyred in his Illinois jail, and Brigham Young took command of the Latter Day Saints in Nauvoo. Young would eventually move the Mormons to Utah territory and transform them into a small nation. The year 1844 was even more important to the Millerites. In 1831, a New York farmer and lay preacher named William Miller founded a Christian cult based on his belief in the imminent return of Jesus. The Jubilee date was eventually determined as October 22, 1844. Of course, the Rapture failed to materialize. Some Millerites lost their minds after the so-called Great Disappointment, but Millerism survived, transforming into Seventh-Day Adventism, which originally believed “the door had shut to heaven” on that day. In 1843 a Millerite named Belle Baumfree, the mother of a Nantucket whaler, changed her name to Sojourner Truth.

The mid-century also saw the development of “New Thought,” a spiritual movement founded on the work of mesmerists, mentalists, and healers such as Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, a New Hampshire clockmaker who taught a doctrine that prefigured twentieth-century “Positive Thinking.” Mesmerism and hypnotism were all the rage, and were frequently combined with the work of mystic philosophers such as Emmanuel Swedenborg. Indeed, Mary Baker Eddy was one of Quimby’s “patients,” and would incorporate his ideas in the founding of Christian Science in 1879.

The Mythos

In terms of the Mythos, 1844 is four years after the death of Friedrich Wilhelm von Junzt and the publication of Die Unaussprechlichen Kulten, two years after the crew of the Kingsport fishing vessel Sabrina were slaughtered off the coast of Innsmouth, and the very year Enoch Bowen returns from Egypt and Dr. Drowne warns Providence about the Starry Wisdom Church. It is two years before Innsmouth will be ravaged by Deep Ones. And of course, 1844 is the year that the player characters sail on the final voyage of the Quiddity.

Art, Literature & Music

In Western art, the 1840s are a transitional period between the Romanticism of the early century and the Realism that would emerge after the revolutions of 1848. J.M.W. Turner is nearing the end of his career, Eugène Delacroix has peaked, and Gustave Courbet is just getting noticed. Still, Romanticism is hardly dead. The Hudson River School is about to produce its famous “second generation,” and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood will be formed in 1848. Symbolism, Impressionism, and Surrealism are decades in the future.

J.M.W. Turner’s Slave Ship (1840)

J.M.W. Turner’s Slave Ship (1840)

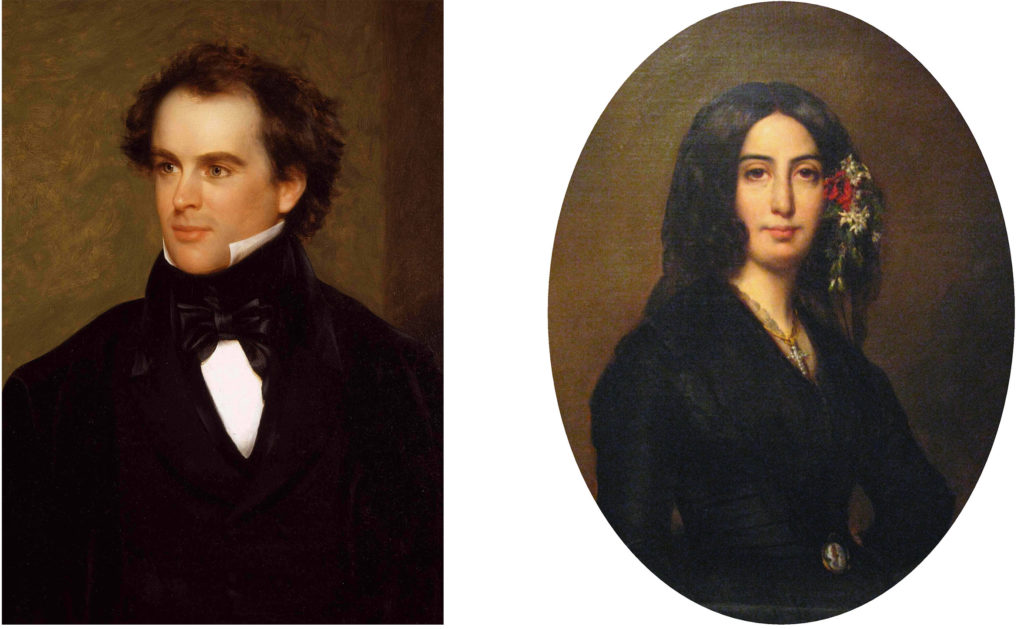

In literature, Britain’s great generation of Romantic poets have passed away, leaving only William Wordsworth, who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1843. Lord Alfred Tennyson has recently revised his Arthurian poem “The Lady of Shalott.” He’ll be appointed Poet Laureate after Wordsworth dies in 1850, his mythical themes inspiring the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. In 1844 Charles Dickens is becoming a household name, having published Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol. Germany is also transitioning from Romanticism. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe died in 1832, and Heinrich Heine has relocated to Paris, becoming increasingly involved in leftist politics. Meanwhile, George Sand, Victor Hugo, and Honoré de Balzac continue to rule the French literary scene. For those with more swashbuckling tastes, Alexandre Dumas has just published The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, but English translations won’t arrive until 1845 and 1846 respectively.

In the United States, the most famous writers are Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, with Cooper’s The Deerslayer hitting the shelves in 1841. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is just getting started, Nathaniel Hawthorne is struggling for wider recognition with Twice-Told Tales, and Edgar Allan Poe is five years from his untimely death. Herman Melville has yet to write a novel; but having been recently been discharged from the Navy, is about to set his pen to Typee. Transcendentalism is on the rise, with The Dial launching in 1840 and Emerson publishing his second series of Essays in 1844.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1840) and George Sand (1838)

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1840) and George Sand (1838)

While Romanticism is waning in art and literature, it still dominates the world of music. Frédéric Chopin is nearing the end of his tragically short career, while Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann, and Charles-Valentin Alkan are in their primes. Living in Dresden, Richard Wagner premièred his haunted opera The Flying Dutchman in 1843, and has begun work on Tannhäuser, which he’ll complete in 1845.

Mid-Century Horror

Turning to a subject close to a Keeper’s dark heart, horror is a well-known genre to mid-century readers, although not by that name. Contemporary readers are more likely to call such stories “supernatural,” “Gothic,” or even “Germanic.” The term Gothic comes from Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story (1764), and was meant to evoke a distant, quasi-medieval atmosphere redolent with secrets. (Walpole mischievously claimed his novel was a “rediscovered” sixteenth-century manuscript.) Otranto touched off a Gothic craze, and writers such as Ann Radcliffe rose to prominence on the strength of books like The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne (1789) and The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). By the turn of the century, Gothic novels were already being satirized, most notably by Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey (1803). The Romantic generation triggered a second wave of Gothic narratives, infused with late Romantic ideals and featuring “modern” anti-heroes. The most famous example is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus (1818), often considered the first science fiction novel. There’s also John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), which introduced the world to Lord Ruthven, and Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), a Faustian parody of Lord Byron.

While supernatural elements were commonplace in nineteenth-century American fiction and permeated the works of Irving, Hawthorne, and Melville, most Gothic narratives in the States revolved around more lurid topics such as Indian captivity and rape. In America, the most famous Gothic novelists were Charles Brockden Brown and George Lippard. Brown is the author of Wieland (1798), a story that combines murder, mesmerism, and mania with spontaneous human combustion. In 1845, George Lippard would publish The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monk Hall. Set in a Philadelphia club that functions as brothel, this muckraking tale of debauchery and hypocrisy would become America’s best-selling novel until unseated by Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852. However, despite Lippard’s contemporary popularity, the figure we most associate with mid-century horror is his friend Edgar Allan Poe, whose stories were written between 1833-1849.

The God of Fiction

In October 1844, Edgar Allan Poe is living in New York City, where he works at the New-York Mirror. A poet, reviewer, and sharp-penned satirist, Poe’s fictional “articles” cover a breathtaking range of subjects and styles: comedic parodies of Romanticism and transcendentalism, Gothic “grotesques and arabesques,” metaphysical dialogues, stories of deductive “ratiocination,” and scientific hoaxes involving balloons, space travel, and mesmerism. A somewhat tragic figure whose wife died from consumption, Poe remains burdened by debt, has a reputation as a drunkard, and struggles with editors over everything from meeting deadlines to toning down his macabre excesses. While modern critics debate whether Poe’s early horror stories were meant as Gothic parodies, by 1844 he’s published his most famous works, with The Raven and “The Cask of Amontillado” soon to follow. In five years, he will die in Baltimore of “mysterious” causes. His poem Annabel Lee will be posthumously published in his obituary.

Pym Illustration by Frédéric Lix and Yan’ Dargent (1864)

Pym Illustration by Frédéric Lix and Yan’ Dargent (1864)

While Poe’s 1838 novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket is among White Leviathan’s primary inspirations, Poe is discussed at length because he profoundly influenced H.P. Lovecraft, who declared him the “God of Fiction.” Poe’s impact on Victorian literature is impossible to overstate. His fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin paved the way for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, while stories like “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” prefigured the “scientific romances” of Jules Verne. He was translated into French by nonother than Charles Baudelaire and into Spanish by Jorge Luis Borges. Reading Edgar Allan Poe is an excellent way to soak up the atmosphere of America in the 1840s, and a few of his more nautically-inclined tales are referenced in the “Bibliography.” Like Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, White Leviathan occupies a world coexisting with Poe’s fiction, where Arthur Gordon Pym is considered a “real” figure, and Poe merely his ghostwriter. Tekeli-li!

White Leviathan > Introduction

[Back to Campaign Introduction |White Leviathan TOC | Forward to Keeper’s Introduction]

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 4 October 2021

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

White Leviathan PDF: [TBD]