Quiddity (Player Version)

- At August 14, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Call of Cthulhu

0

0

Long seasoned and weather-stained in the typhoons and calms of all four oceans, her old hull’s complexion was darkened like a French grenadier’s, who has alike fought in Egypt and Siberia… Her ancient decks were worn and wrinkled, like the pilgrim-worshipped flag-stone in Canterbury Cathedral where Becket bled… She was a thing of trophies. A cannibal of a craft, tricking herself forth in the chased bones of her enemies… A noble craft, but somehow a most melancholy! All noble things are touched with that.

—Herman Melville, “Moby-Dick,” Chapter 16

Introduction: Player’s Version

The players characters’ home-away-from-home for three years, the Quiddity is of central importance to White Leviathan. This section examines the Quiddity in detail. “Part I: Overview” gives her background and introduces basic nautical terminology. “Part II: Sails & Rigging” explores the world of square-rigged sailing ships. It offers more advanced jargon, and describes the fundamentals of sailing. “Part III: Description” details the decks and interior of the Quiddity, from her mermaid figurehead to the captain’s cabin.

Player Note: Learning the Ropes

The following descriptions are designed to introduce just enough jargon to add salt to the game, but not enough to become overwhelming. Don’t worry about absorbing everything in one sitting, and trust that your Keeper will introduce things gradually. Just remember, White Leviathan is a game, and the idea is to have fun. While “learning the ropes” certainly adds authenticity and color to the campaign, White Leviathan may be enjoyed using general terms. Of course, if any player has a particular interest in nautical settings, they should feel free to share that knowledge with the Keeper—a Patrick O’Brian fan makes a wonderful resource!

| Key Terms Having said that, a few key terms must be understood, even by lubbers. The front of a ship is the “bow.” The “prow” is the part of the bow that’s above the water. The rear of the ship is the “stern.” While onboard a ship, “fore” is towards the front and “aft” is towards the rear; when used as prepositions, they become “afore” and “abaft.” The ship’s bottom is the “keel,” which runs from “stem to stern.” The maximum width of the ship is its “beam,” and the distance from the waterline to the keel is its “draft.” The right side of a whaler is the “starboard” side and the left side is “larboard”—whaling ships scorn the new-fangled term “port.” The side facing the wind is “windward,” also called the “weather” side. The side away from the wind is “leeward.” |

Part I. Overview

A ship is largely defined by The Quiddity began her life in 1826 as the Alice Thatcher, a Boston merchantman named after the owner’s wife. After the owner fell from the crosstrees while demonstrating he “can still climb like a monkey,” his bereaved widow sold the ship to the Tuttles. Placed in charge of her conversion to a whaler, Captain Gideon Sleet thought her name an invitation to misfortune—“Might as well call her the goddamn Widowmaker!” Although renaming a ship is also considered bad luck, he rechristened her the Quiddity, a word he’d plucked from the pages of his dusty library. Of course, most sailors don’t know the meaning of the word, and erroneously believe “Quiddity” to be an Indian tribe, or possibly a species of mermaid.

The Quiddity is loosely modeled on two historical whaling ships: the Lagoda, which has been replicated in half-scale at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, and the Charles W. Morgan, now preserved as a floating museum at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut. Both of these ships have been thoroughly documented, providing a ready supply of photographs, models, diagrams, and blueprints that may be cosulted as visual aids. Even better, a trip to Mystic Seaport allows you to actually walk the decks of the Quiddity! (Er, the Charles W. Morgan.)

A ship-rigged Charles W. Morgan. Photograph by Edwin Hale Lincoln.

A ship-rigged Charles W. Morgan. Photograph by Edwin Hale Lincoln.

Crew

When the Quiddity departs Kingsport on November 1, 1844, she has the following officers, passengers, and crew:

Master

Captain Jeremiah Joab

Chief Mate

Mr. William Bliss Pynchon

Second Mate

Mr. Joseph Coffin

Third Mate

Mr. P.H. Whipple

Boatsteerers

Quentin Shaw, Ulysses Dixon, Matty Shoe, Quakaloo

Shipkeepers

Leland Morgan—Blacksmith; Stanley Ruch—Carpenter; Joseph Lovecraft—Cooper; Natty Weeks—Cook; Thomas Plunkett—Steward

Seamen

Peter Veidt, Owen Love, Henry Swain, Ricardo Reis, Pig Bodine, Suresh Joshi, Lou Kanaka, Virgil Caine, Zim Folger, Israel Reed, Tom Redman, Milton Redburn, Tobias Beckett, Duke Nelson, Paddy Garcia, Isaac Townshend, James Cabot, William Crow

Cabin Boy

Benjamin Coffin Warnock

Surgeon

Dr. Montgomery Lowell

Part II. Rigging & Sailing

A ship is largely defined by its sails and rigging. Unfortunately, this is where the nautical jargon becomes the most complicated. The following overview explains the Quiddity’s sail plan in a fair amount of detail. It also covers basic nautical maneuvers, such as tacking and heaving-to. Players less interested in nautical authenticity may skim this section and go right to the “Quiddity Description.” See “Learning the Ropes” above if you seek absolution for just looking at the pretty pictures!

1. Masts

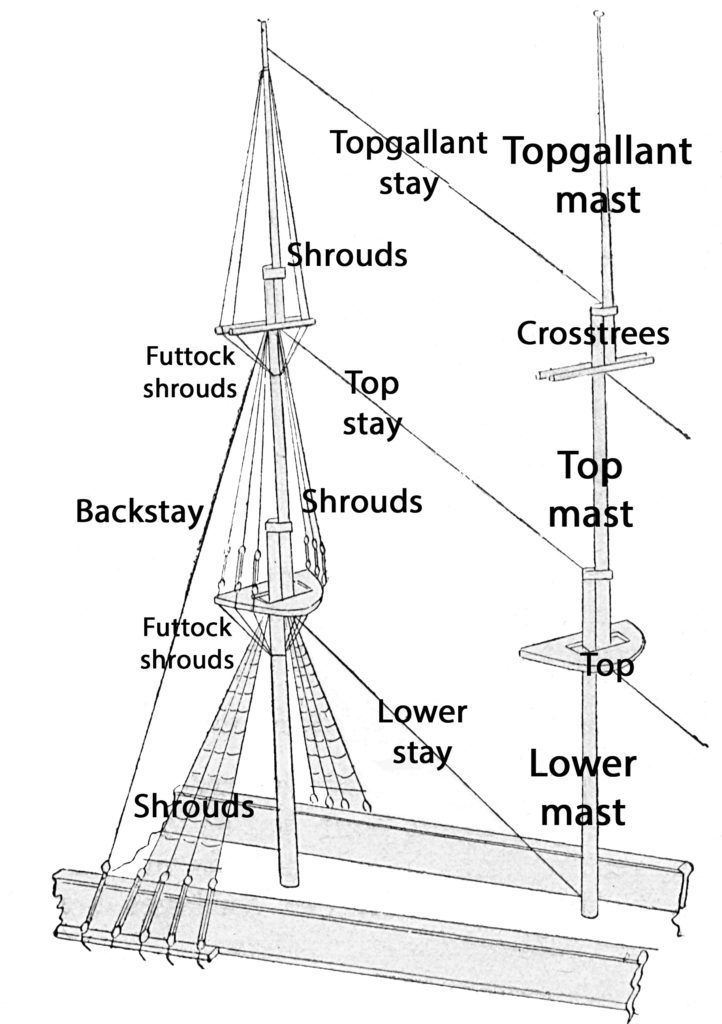

Our voyage into the world of rigging begins with spars, which are sturdy, wooden poles of various sizes and lengths. Vertical spars are called “masts.” The primary job of a mast is to support horizontal spars such as yards, booms, and gaffs—these hold the sails, and are explained below. The Quiddity has three masts, moving from bow to stern: the foremast, the mainmast, and the mizzenmast. Each mast is composed of three shorter masts lashed together: the sturdy lower mast, the narrower topmast, and the narrower-still topgallant mast. The joints where one mast is fastened to another are marked by platforms or struts which anchor the rigging above. The lower platform, where the lower mast joins the topmast, is called the “top.” The higher platform, where the topmast joins the topgallant mast, is called the “crosstrees,” and is formed from two short spars. Each topgallant mast is capped by a wooden disc called a “truck.”

Masts are bolstered by a network of rigging. The lines that support a mast from the fore and aft are called “stays.” The lines that support a mast from the sides are called “shrouds.” The shrouds supporting the lower mast are attached to “chainplates” on the ship’s flanks. These also provide ready grips for pirates crawling up the side with knives clenched in their teeth! The shrouds supporting the upper masts are anchored to the top and the crosstrees. They’re crossed by horizontal “ratlines,” which give sailors footholds when climbing the rigging. The ratlines gives shrouds their characteristic web-like appearance. On some ships, wooden “battens” are used instead of ratlines. In order to stabilize the upper rigging, the top and crosstrees require “futtock shrouds.” These webs of rope connect the sides of each platform to the mast below.

Over the Top

The futtock shrouds offer sailors a unique challenge. When a sailor is going aloft, he first climbs the lower shrouds using the ratlines. Upon nearing the “top,” he must reach up to the futtock shrouds to continue his climb. In other words, the sailor must lean backwards and climb upside-down for a spell! Now, because this is terrifying, most ships possess “lubber holes.” These are openings in the platform that allow a climber to skip the futtock shrouds and simply pass through the hole to reach the top. Experienced sailors scorn this convenience and always go “over the top,” the origin of the popular phrase. Once the top has been gained, the process must be repeated to reach the crosstrees—but now the sailor is even higher above the deck. For safety’s sake, a ship’s rigging must be kept tarred, mended, and tidy. A sailor’s life depends on it!

Standing Masthead

Sailors dispatched aloft for lookout duty stand on the crosstrees, their arms wrapped around the topgallant mast for support. (A Pacific whaler scorns the semi-enclosed crow’s nest used in the Greenland fishery, and metal lookout hoops weren’t added until later in the nineteenth century.) The mastheads are manned from the moment the ship leaves port; from sunrise to sundown, under all weather conditions except for storms and dangerous heat. Usually the foremast and mainmast lookouts are posted, but a scout may be sent up the mizzenmast if needed. Foremasthands and harpooneers alike are expected to stand lookout. Because standing masthead is a common shipboard duty, Climb rolls are only needed under adverse conditions. Lookouts take turns in two-hour shifts. When a spout is sighted, the lookout points and cries, “There she blows!” or, if the whale is seen to breech, “There she breeches!” An officer calls up for more information, and the boats are launched. Some sailors loathe lookout duty, while others prize the solitude. Standing masthead is a prime time for daydreaming, and is favored by sailors with a philosophical bent—it’s an excellent place for an Idea roll. However, a lookout must remain cautious. If a pleasant reverie slips into a doze, or boredom tarnishes into dullness, a carless sailor may find himself tumbling to deck!

Spotting a Whale

Under fair conditions, a spouting whale may be seen up to eight miles away. This requires a Spot Hidden roll, with each additional whale granting a +1D10 bonus die, up to a maximum of +3D10. Once a lookout has spotted a whale, he may identify its species with a Whalecraft roll. After three successful calls, that species may be automatically identified.

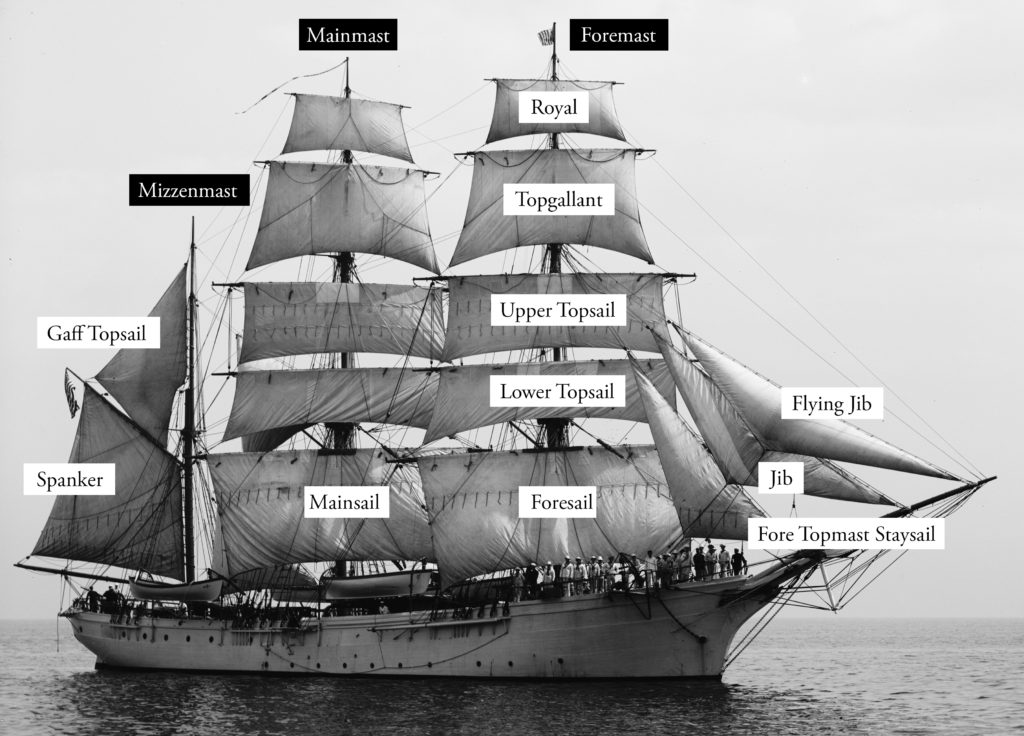

2. Sails

Sails are broadly divided into two types, depending on how they align with the ship’s keel. “Square” sails are set perpendicular to the keel, and “fore-and-aft” sails are parallel with the keel. Square sails are trapezoidal in shape—again, “square” refers to their alignment with the keel—and are the primary sails that propel the ship forward. They’re suspended from “yards,” horizontal spars that give the mast its cruciform appearance. The ends of a yard are called “yardarms.” Yards may be partially rotated around the mast to allow the sails to catch the wind; this is called “trimming” the sails, and is accomplished by hauling on “braces,” long ropes attached to the yardarms. Braces run down to the deck level, allowing sailors to control the yards more readily. Ropes running underneath each yard provide footholds for sailors working the yard; these are called “Flemish horses,” or just “horses.”

The Quiddity’s foremast carries four sails, listed in order of increasing elevation: the foresail, also known as the fore course; the fore topsail, the fore topgallant, and the fore royal. This pattern is repeated at the mainmast, which holds the mainsail or main course, the main topsail, the main topgallant, and the main royal. Larger ships may also carry “skysails” and “moonrakers,” but these are rare on a whaler. If the weather is fair and the captain’s in a hurry, the yards are extended and studding sails are set. Projecting from either side of their working sail like giant ears, “stuns’ls” allow the ship to harness all available wind power.

Fore-and-aft sails are aligned parallel with the keel. The most common is the “staysail,” a triangular sail with its leading edge attached to a stay. Found at the front of a ship or suspended between masts, staysails assist in reaching and tacking, and provide extra stability for a ship under full wind. Staysails located at the front of the ship are called “jibs,” with the celebrated flying jib being the ship’s leading sail. Sails in front of the foremast are collectively called “headsails.” Fore-and-aft sails may also be mounted to spars projecting from the mast. By rotating around the mast, these spars allow the sail to swing back and forth as needed. A spar holding a fore-and-aft sail from the top is called a “gaff,” while a “boom” secures the sail from the bottom. The Quiddity’s mizzenmast supports a pair of fore-and-aft sails: a gaff topsail and a “spanker,” sometimes called a “driver.” Both are used for steering.

Bark-Rigging

A vessel’s sail plan helps determine what type of ship it is. Like many whalers, the Quiddity is a “bark”—she carries square sails on her foremast and mainmast, and fore-and-aft sails on her mizzenmast. Bark-rigging allows a ship to be managed with a reduced crew, such as during a whale hunt. The Salmon P. Chase above provides an excellent example of bark-rigging. The only difference is her “double topsail.” An innovation originating with clipper ships in the early 1840s, double-topsails weren’t used on whalers until much later. The Quiddity carries single topsails, which are notoriously unwieldy.

| Using Photographs as Visual Aids There are no contemporary photographs of the Charles W. Morgan. Many early twentieth-century photos show the Morgan as ship-rigged, which means all three masts are rigged with square sails. The Lincoln photograph is a good example of this. On the other hand, while modern photos of the Morgan are quite spectacular, they depict her with double-topsails. While these details are hardly game-breaking, groups dedicated to authenticity should keep this in mind when using visual aids! |

Parts of a Sail

Our salty discourse continues with the anatomy of a sail. On a triangular fore-and-aft sail, the edge facing forward is the “luff,” the edge facing aft is the “leech,” and the bottom is the “foot.” The topmost corner where the leech meets the luff is the “head.” The fore corner where the luff meets the foot is the “tack.” The aft corner where the leech meets the foot is the “clew.” On a quadrilateral fore-and-aft sail such as a spanker, the top edge is called the head; the fore corner is the “throat,” and the aft corner is the “peak.” A square sail maintains these basic terms: the top edge is the head, the bottom the foot, and the sides the leeches. However, when the wind is coming across the beam, the “weather leech” may be called the “luff.” The top corners are “head cringles” and the bottom corners are clews; although the clew facing the wind may be called the “tack.”

Reefing

A sail does not have to be completely unfurled. A portion of its canvas may be rolled up to reduce its surface area. This is called “reefing” the sail. Most large sails like courses and topsails have two or three distinct “reef points” marked by rows of dangling straps. Untying the reef points of a “shortened” sail is called “shaking out” a reef.

3. Lines

Generally speaking, sailors refer to ropes as lines, and each has its own special name. (Are you surprised?) Shrouds, stays, ratlines, and braces have already been discussed. The lines used to haul up spars, sails, and flags are called “halyards.” “Clewlines” are connected to the clews of a sail, and lift the sail; as are “buntlines,” which run across the body of the canvas. “Sheets” are also connected to the clews of a sail, and are used to stretch out the corners.

| Talk Like a Sailor! Sailors often slur the syllables of nautical words, much the way Gloucester is pronounced “Gloster,” or boatswain is pronounced “bosun.” For instance, mainsail is pronounced “mains’l,” staysail is “stays’l,” and studding sail is “stuns’l.” Topgallant is pronounced “t’gallant,” and topgallant sail becomes the even-more bizarre “t’garns’l.” The words “line” and “mast” are slurred as well, usually pronounced “lin” and “m’st” when following another word. For instance, ratline sounds like “ratlin,” bowline is “bowlin,” and mainmast topsail becomes “mainm’st tops’l.” Nor is this confined to rigging. Bulwark and gunwale are pronounced “bullark” and “gunnel,” and of course forecastle is “fowks’l.” Also, just to make things more confusing, forward is pronounced “fo’ard,” leeward is “loo’ard,” and in the 1840s, block-and-tackle was pronounced “block-and-tay’kl.” |

4. Under Sail

The art of sailing requires many arcane evolutions, each with its own esoteric vocabulary of terms, phrases, and slang. While much of this can be safely ignored for White Leviathan, a few basic maneuvers may provide useful while navigating the Quiddity. Put as simply as possible, sailing directly downwind is called “running,” and sailing across the wind is “reaching.” Square-rigged vessels are essentially built to run with the wind, and aren’t very good on a “beam reach,” where the wind is blowing perpendicular to the hull. Sailing against the wind is more tricky, and is made possible by Bernoulli’s Principle. The bow is angled into the wind, and the yards are braced so the sails are “close-hauled” with the wind. This deforms their shape into something similar to an airplane wing, with the pressure differential generating lift from the leeward side. This lift is opposed by the force of the water against the keel and rudder. The resulting vector pushes the ship forward, but at an angle. It also tilts, or “heels” the ship leeward. Unfortunately for the Quiddity, square-riggers aren’t good at sailing close to the wind, and only move forward at a 60-70° angle. A ship moving thusly is said to be on the windward “tack,” whether that’s starboard or larboard.

While this provides forward motion, it also carries the ship increasingly off course. Eventually the ship must turn and move forward in the opposite direction. Turning a ship’s bow against the wind is called “tacking,” and requires some deft handling of the sails. Not only must the ship be turned directly into the “eye” of the wind—an action that spills the wind and “luffs” some sails while “backing” others against the mast—the wind must be regained on the opposite tack as quickly as possible. Sailors pride themselves on their ability to tack quickly and cleanly—nothing appears more lubberly than botching a tack, a time-consuming mistake called “missing stays.” A stalled ship is at the mercy of the wind and waves, and is said to be “in irons.” By making a series of tacks, a ship may travel against the wind in a zig-zag pattern. This is called “beating” into the wind.

An alternative to tacking is “wearing,” in which a ship turns to place its stern against the wind, then swings around to reverse direction. While easier to accomplish than tacking, wearing requires more space, takes more time, and moves the vessel in a loopy, corkscrew pattern that’s “two steps forward; one step back.” However, despite these disadvantages, most square-rigged ships prefer wearing to tacking, especially with less experienced crews. Although the following diagrams depict a ship-rigged vessel, the bark-rigged Quiddity makes similar maneuvers, with the spanker taking a supporting role from the mizzenmast.

|

|

|

Tacking and beating windward. Sails are luffing at point 3

|

Wearing from a larboard to starboard tack, and the resulting forward motion

|

The final maneuver is “heaving to,” which slows or halts the momentum of the ship. This is performed by arranging the sails and rudder to play against each other. It usually involves “backing the sails”—a kind of reverse where the wind plasters the canvas against the mast. “Heave to” is also slang for stopping the ship. For instance, “What an island! We hove to and dropped anchor, and the native girls swam out to meet us!”

Part III. Quiddity Description (Keeper)

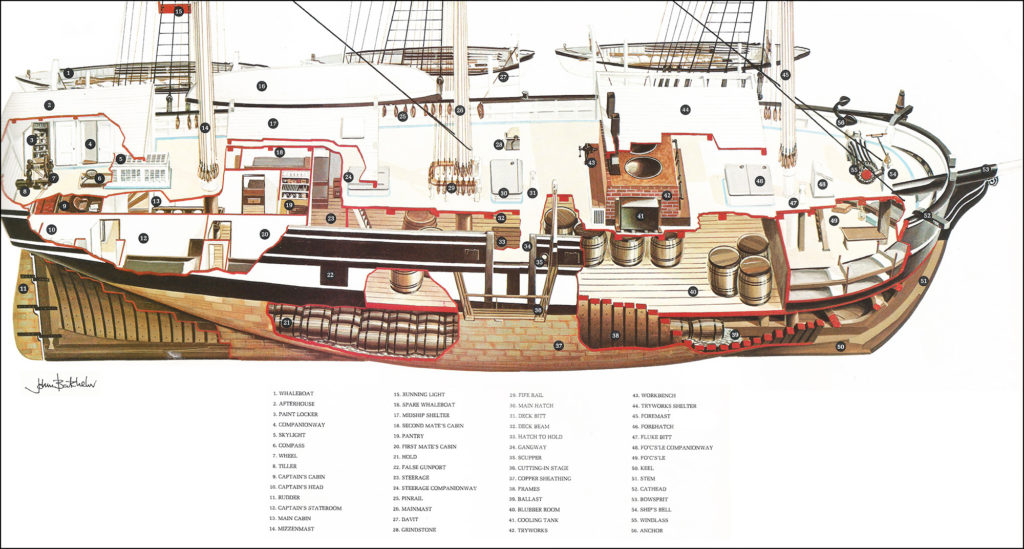

The following is a spoiler-free description of the Quiddity from stem to stern. Until the time that White Leviathan gains original artwork, this section is borrowing the Lagoda cutaway from A.B.C. Whipple’s The Whalers, Time-Life Books, 1979. As this book is regrettably out of print, John Batchelor’s magnificent drawing has been replicated below. Click the image to enlarge. Throughout the following text, numbers in parentheses correspond to numbers on Batchelor’s diagram.

1. General Appearance

Made from solid oak with a copper-fastened bottom, the Quiddity is a sturdy whaler of average size: 371 tons. Rigged as a bark and fitted with five whaleboats, she’s 108 feet long with a beam one-quarter that length and a draft of 18 feet. She carries an ample midship shelter and an afterhouse covering her steering wheel, but her tryworks are fully exposed. The Quiddity is painted handsomely, black and white with vermillion trimming and the usual false gunports. A large American flag is flown from her aft rigging, and a gaily-painted mermaid pennant flutters from her mainmast. She sports her name in bold letters on her stern, and the ship’s harpoons are engraved with a stylized “Q.” Although the Quiddity has logged only three voyages as a whaler, she’s well-appointed for her purpose, boasting scrimshaw decorations and a bowsprit lined with whale teeth. Her hemp lines are sturdy, and Mr. Pynchon makes sure the ropes are well-tarred and the deck holystoned to perfection.

2. Masts & Spars

A) Masts

The Quiddity has three masts, moving from bow to stern: the foremast (45), the mainmast (26), and the mizzenmast (14). The Quiddity’s masts are painted white. Each features an 8”-wide brass band encircling the mast at eye-level. These bands are inscribed with constellations, their Latin names engraved in handsome Roman capitals. The foremast features circumpolar constellations, the mainmast depicts the Zodiac, and the mizzenmast shows prominent Southern constellations. Spare spars are lashed vertically to the mainmast, and extra poles for lances and harpoons are lashed to the foremast.

B) Bowsprit and Catheads

The “bowsprit” (53) is the long spar projecting from the ship’s prow. Its job is to anchor the forestays—the taut cables that secure the masts. It also contains the jib-boom, which secures the triangular jib-sails leading the ship. The “catheads” (52) are located on either side of the bowsprit. These sturdy extensions stay the jib-sail lines and help fasten the anchors to the bulwarks. The Quiddity’s catheads are capped in bronze, each cheerfully molded in the face of a grinning cat. The term is also used as a verb: “to cat-head an anchor” means to fasten it tightly to the side of the ship. The ship’s figurehead is mounted just beneath the bowsprit.

3. Figurehead

Carved by Erasmus Doppler & Sons, the Quiddity’s figurehead is a naked mermaid with flowing red hair. Her upper body is painted white with rosy-red nipples—no modesty here! Her lower body takes the shape of a scaly fish, her viridian flukes curled beneath the bowsprit. She emerges from a burst of carved foam; elegant rococo waves flecked with Marsh gold. Informally dubbed “Flora” by Captain Sleet, the mermaid is commonly called “Quiddy”; or when the sailors are in a more saucy mood, “Cunny Quid.”

4. Whaleboats

The Quiddity has five whaleboats (1) prepared on arched davits (27). The three boats on the larboard side are the “mate’s boats.” The two boats on the starboard side are the “captain’s boat” and the “spare boat.” Two additional spares are inverted atop the midship shelter (16). The elevation of the boats may be adjusted to accommodate wind and weather, and during particularly fierce storms, they may be removed from their davits and lashed to the deck. When a whale is sighted, the boats are lowered from the davits using a pulley system. Whaleboats are described further under “The Whaleboat.”

5. Decks & Bulwarks

A) Decks

The Quiddity’s deck is a level surface running from the windlass to the stern taffrail. The area behind the mainmast is commonly referred to as the “quarterdeck,” though it lacks the increased elevation customary to that hallowed region. As dictated by nautical tradition, the quarterdeck is reserved for officers and shipkeepers. The only foremasthands allowed to approach are the designated helmsman and the cook’s assistants.

B) Bulwarks

The “bulwark” is the part of the hull that extends past the deck—it’s essentially the wall surrounding the deck. (Not to be confused with “bulkhead,” which is an interior, load-bearing wall.) The ship’s gangway (34) is located amidships on the starboard side. The bulwarks on either side can be removed to facilitate lowering the cutting stage. Rain or seawater that collects on deck is drained through the “scuppers,” channels located along the lower bulwarks.

C) Rails

The bulwarks are set with “pinrails” (25), slotted pegboards used to secure lines of rigging. The removable pegs are called “belaying pins.” Lines are secured by wrapping them around the belaying pin in a figure-8 pattern. Belaying pins are quite sturdy, and may be added or removed as needed. They also make handy clubs during a sudden fracas!

The base of the mainmast is surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped railing called a “fife rail” (29), a free-standing pinrail used to secure the halyards. Like most whalers, the Quiddity’s bulwarks are set with “lashrails” where casks of hot oil are secured for cooling. A spare topmast is fastened to the larboard lashrail. The ship’s stern railing is the “taffrail.” The ship’s life buoy is located here, mounted on a spring and trailing a length of sturdy hemp. Little more than a floating cask, the buoy is lined with segments of rope ending in knotty “Turk’s-heads,” so-called for their resemblance to a “Mussulman’s” turban.

D) Hatches and Companionways

The interior of the ship may be accessed through hatches and companionways. A “hatch” is just an opening on deck, while a “companionway” is a ladder or stairs. The Quiddity has five hatches and companionways. Moving fore-to-aft, the first is the fo’c’s’le companionway (48). Sheltered inside a wooden “scuttle” resembling a tiny hut, it’s found between the windlass and the foremast. Next is the forehatch (46), located just behind the foremast and providing access to the blubber room. The main hatch (30) is directly in front of the mainmast. It provides access to the blubber room, along with the hold below that. A smaller “booby hatch” afore the midship shelter opens on the steerage companionway (24). And finally, the cabin companionway (4) is reached through a door in the afterhouse.

6. Additional Deck Features

A) Windlass (55)

Used for hauling up the anchors, cutting-in whales, and raising new masts, the windlass is a horizontal cylinder, or “barrel,” fixed between two iron “cheeks.” Iron rods bolted along the wooden barrel provide additional support for the anchor cables. The windlass is turned by manual labor: sailors insert handspikes into the top of the barrel and crank down with all their might. After a 90° rotation, the handspike is removed and re-inserted at the top. It requires sixteen men to operate at full power. (A later innovation replaced the handspikes with a pair of pumping handles.)

B) Ship’s Bell (54)

The ship’s bell is located above the windlass. A bronze bell with a pleasant and sonorous tone, it was cast in Arkham and is engraved with the name “QUIDDITY.” The rim is chased with constellations, including Orion the Hunter and Cetus the Whale.

C) Head

Most whalers do not feature a privy for the foremasthands, who “do their duty” over the side of the ship. However, if a woman is to become a permanent fixture onboard the Quiddity, a small wooden outhouse is constructed along the larboard bulwark near the windlass. Waste is channeled down a zinc chute directly over the side of the ship. This privy is meant for the sailors, thus sparing the woman the sight of indecent acts. The woman herself uses a chamber pot in the “henhouse.”

D) Forge

During the first week of Pacific whaling, the ship’s portable forge is hauled up on deck and lashed to the foremast. From then on it operates continuously, the blacksmith attending to a myriad of harpoons, lances, spades, knives, pikes, gaffs, and hooks.

E) Bilge Pump

Located behind the mainmast fife rail, the Quiddity’s bilge pump is powered by two long pump-handles. It requires four men to work efficiently. It can also be used to pump seawater through a canvas hose.

F) Deck Prisms

Thick wedges of glass set into the planking, deck prisms allow sunlight to pass into the interior. Their shape is designed to amplify the light. Being somewhat fragile, deck prisms are only located above the steerage section and the main cabin. Also, common foremasthands don’t need such luxuries as daylight!

7. Anchors

The Quiddity features two large anchors (56), one on either side of the bow. Each is attached to a prodigious iron chain, commonly called a cable. The standard length of a cable is 120 fathoms, or 720 feet. In fact, sailors use “cable” as a unit of length—“There’s a mermaid two cables off the starboard bow! Oh, wait, it’s just another sea-cow.” The cables originate in the anchor locker, sometimes called the “chain pit,” a rectangular cabinet in the center of the hold. The cables are threaded through anchor pipes and emerge on deck just behind the mainmast. They run along the deck to the windlass, which provides the mechanical power needed to raise and lower the anchors, and thence forward to the “anchor deck.” An elevated, triangular platform tucked into the bow of the ship, this sturdy area shelters the cables as they pass through the “hawse pipes” and out the “eyes” on either side of the bow. The anchor deck also protects and reinforces the mainmast forestays.

Charles W. Morgan windlass and anchor deck. Note pinrail at right. Photo by Daryl Carpenter.

Charles W. Morgan windlass and anchor deck. Note pinrail at right. Photo by Daryl Carpenter.

When not in use, the anchors are secured to catheads and lashed to “anchor boards” along the bulwarks. Occasionally the anchor cables are hauled from the chain pit and cleaned. This is an unpleasant task, as the sailors must chip, scrape, and pound the rust from the iron links. Working under the hot sun, it may take several days to complete the overhaul. The cleaned cables are thoroughly greased and returned to the chain locker.

Kedging

The Quiddity’s larboard anchor is smaller than the starboard anchor, and is sometimes used for “kedging,” a maneuver used to pull a vessel forward using an anchor. For example, if the ship becomes stuck on a reef. The anchor is transported to a fixed point, perhaps an outcropping of rock or another part of the reef. The windlass is used to winch the ship forward, hopefully freeing it from its precarious position. Sometimes called “warping,” this maneuver may also be employed to move a ship against the wind.

8. Cutting-Stage

The cutting-stage (36) is a portable platform lowered over the side of the ship so workers can access a dead whale. It’s made from three wide planks fastened together to resemble the perimeter of a rectangle with one side missing. A running handrail provides additional support. When not in use, the cutting-stage is stored in a raised position above the bulwarks near the gangway.

9. Tryworks

The tryworks (42) are where slabs of whale blubber are rendered into oil. The Quiddity’s tryworks consist of two 250-gallon iron cauldrons nestled in a brick kiln. The firebox is separated from the deck by a brick reservoir called a “duck pen.” This protects the wooden deck from the intense heat. Starting up and directing the tryworks is the job of the second mate, and the harpooneers usually take shifts rendering the blubber. Two copper cooling tanks (41) are located on either side of the kiln. (See “Trying-Out a Whale” for details.)

A Popular Hiding Place

Occasionally during the night watches, sailors are known to lift the cover from a try-pot and sneak inside the cauldron for a nap. If caught, this brings a terrible reprimand. On the Quiddity’s last cruise, Mr. Whipple punished a derelict greenhorn by ordering him confined inside a trypot for an afternoon of roasting in the hot sun!

Homeward Bound!

A common ritual onboard a homeward-bound whaler is to disassemble the tryworks and throw them into the sea, brick by brick. For vessels returning from long voyages, this includes the iron trypots as well, which have become weakened from years of frequent use. The ritual is accompanied by much celebration.

The Fire of ‘39

Some whalers enclose their tryworks inside a wooden shelter. This protects the tryworks from rain and prevents sparks from reaching the rigging. The Quiddity used to be such a ship. Then one night in 1839, heavy seas roiled the cauldrons and the shelter caught fire. Spreading on a burning slick of oil, the blaze consumed half the deck. Two seamen lost their lives—Hank Illsley, a Kingsporter who perished when the shelter collapsed, and Harry Kanaka, a Hawaiian who leapt overboard to extinguish himself and was never seen again. Veterans of that voyage remember the night vividly, and a few bear physical scars: Peter Veidt’s left hand was burned, and Natty Weeks carries a warped checkerboard on his back where flaming rigging smoldered into his flesh, the tar preventing its quick removal. Second mate Jacob Macy received the worst of it, forced into retirement with a disfigured face. Rather than re-build the shelter, the crew unanimously opted to leave the tryworks uncovered, rain be damned. The two lost sailors are memorialized by inscriptions engraved on the new cauldrons: HENRY BARTHOLEMEW ILLSLEY, HARPOONEER, 1812-1839, GOD REST HIS SOUL on the larboard pot, and HARRY KANAKA, 1818-1839, HOME AT LAST on the starboard pot. Seamen who never knew these sailors have somewhat disrespectfully dubbed the pots “Hank and Harry.”

10. Workbench & Hen-Coop

A) Workbench (43)

Located behind the tryworks, the workbench contains the majority of the ship’s tools for carpentry and general repairs. A vice is mounted on the larboard side, and the ship’s grindstone (28) is located just behind the bench. Stanley Ruch, the Quiddity’s carpenter, is very protective of his space, and seamen are not expected to fiddle around with his tools. The bench is decorated by two hex signs, carefully carved from wood and gaily painted—a Wilkommen double-distelfink, and an 8-pointed “Abundance & Goodwill” star.

B) Hen-Coop

The space between the legs of the bench is floored and slatted, used as a hen-coop for the officer’s chickens. The steward Thomas Plunkett dislikes the hens intensely, but Ruch treats them affectionately, and has named several of the more idiosyncratic birds. The ship’s swine are also found in this area, but their numbers diminish steadily as the voyage progresses.

11. Midship Shelter

Located between the mainmast and mizzenmast, the midship shelter or “forward house” (17) is little more than a wooden canopy stretched across the width of the ship. Offering some protection from the elements, the shelter contains a cabinet of spare tools and four vegetable bins. Racks mounted under the ceiling support numerous spades, harpoons, and lances, while pegs around the outside edges are hung with pails and buckets. On top of the roof are skids for two spare whaleboats (16), lashed upside-down to protect against rain. Because skid-beams are called “gallows,” Whipple occasionally uses this grim term to refer to the entire shelter—“Say that again, cachorro, and you’ll be hanging from the gallows!”

A) Steerage Companionway

The steerage companionway is located just afore the midship shelter, protected by the “booby hatch.”

B) The Henhouse

If it becomes necessary to berth a woman onboard the Quiddity, the carpenter is ordered to construct a small cabin at the rear of the midship shelter. While the “henhouse” offers some privacy, it’s necessarily cramped, containing only a small bunk, a newly fashioned sea-chest, and a chamber pot. Portholes admit fresh air and sunlight, but the ship can’t spare extra glass, so they’re covered by wooden shutters. The occupant is free to customize the henhouse as she sees fit.

13. The Afterhouse

The afterhouse or “hurricane house” (2) is a roofed shelter that covers the quarterdeck behind the mizzenmast. It contains an alley cutting through the center, dividing the structure into larboard and starboard halves. The shelter ends three feet from the taffrail, forming a narrow stern balcony. (This is different from the Charles W. Morgan’s afterhouse depicted below, which encloses the stern.) Supplies are lashed to the top of the afterhouse, including spare poles, oars, line-tubs, and extra whaleboat gear.

From Ben Lankford’s “Charles W. Morgan,” 1997

From Ben Lankford’s “Charles W. Morgan,” 1997

A) Skylight (5)

The ship’s skylight is a long wooden rectangle set with leaded glass windows. It begins a few feet behind the mizzenmast and runs along the deck into the afterhouse, terminating just before the helm. Its purpose is to let sunlight into the cabin below. The wooden panes are hinged, which allows the circulation of fresh air when weather permits. A brass plaque mounted at the aft end of the skylight is engraved:

THE WIND AND WAVES ARE ON ALWAYS ON THE SIDE OF THE ABLEST NAVIGATORS.

—EDWARD GIBBON

The ship’s parrot, Loki, is often found perched in a cage suspended below the skylight, hanging above the table of the main cabin. During storms, the skylight is covered with a canvas tarpaulin.

B) Compass and Binnacle

Suspended in the skylight coaming above the captain’s desk is the ship’s “transparent” two-sided compass (6). This clever design allows both the captain in his cabin and the officer on deck to take their bearings. A wooden binnacle near the helmsman holds a second compass, a sextant, the ship’s lead, an hourglass, spare oil, and a lamp that’s kept burning twenty-four hours a day. The captain’s spyglass is also stored here, and expensive model from Spencer Browning & Rust.

C) Cabin Companionway (4)

Located at the larboard fore of the afterhouse, this door opens on a cramped staircase leading to the cabin below. Foremasthands are not allowed to enter without permission. A row of wooden bins mounted above the staircase serves as the Quiddity’s flag locker.

D) Paint Locker (3)

Situated directly aft the companionway, the ship’s paint-locker contains flammable items such as paint, tar, and varnish. It’s generally kept locked; as Whipple says, “To prevent the scurvy dogs from drinking the goddamn varnish!”

E) Galley

The galley is located at the starboard fore of the afterhouse. It’s the usual place to find Natty Weeks. A scrimshaw cross decorates the wall, along with an expensive whetstone he’s possessed since Baltimore. The Quiddity’s “doctor” keeps a clean galley, scouring his cookware with lye he derives from a pan of ashes. Natty named the cast-iron stove “Bertha” for no reason he cares to disclose. The two-pronged fork used to dish out salt junk is traditionally called “the tormentor.” One night last voyage, Stanley Ruch used Morgan’s forge to added a little devil-tail to the end.

Staples

Though spread between the galley, pantry, and hold, this is a good place to list the ship’s culinary supplies: flour, meal, mess beef, prime pork, pork hams, mackerel, tongues and sounds, codfish, molasses, vinegar, lemon syrup, pickles, sugar, butter, cheese, raisins, rice, dried apples, beans, peas, corn, potatoes, onions, cabbages, souchong tea, chocolate, mustard, black pepper, cayenne pepper, ginger, allspice, cloves, cinnamon, saleratus, pepper sauce, table salt, sweet oil, coffee, and cheap barley coffee. (Most of this is reserved for the cabin; the forecastle rarely sees anything but salt junk and burgoo!) The “medicinal stores” include lime juice, wine, apple-jack, brandy, gin, and rum. There’s also several kegs of beer, but this must be consumed early in the voyage before it spoils.

F) Stowage

Colloquially known as the “bosun’s locker,” this storeroom holds extra rope, tackle, hatchets, paintbrushes, and other equipment needed by the deck crew. It also contains three sets of iron shackles and bilboes, “just for emergencies.”

G) Helm

At the stern of the Quiddity is the “shin-breaker,” the ship’s steering mechanism (7). A large wheel mounted on the end of a heavy tiller (8), the shin-breaker is raised a few inches off the deck. When the wheel is turned, a system of ropes and pulleys moves the tiller into a new position, with the rudder below amplifying the change of direction. A wooden housing behind the helm covers the tiller. Opening its lid exposes the rudder below, offering a clear view down to the water. After a greenhorn named John Starbuck was caught using the housing as a toilet, the crew began calling it the “Starbuck head.”

Steering the Ship

A shin-breaker is a challenging helm to manage. During heavy seas, the motions of the rudder cause the mechanism to swing back and forth. The helmsman needs to match his Strength against the Strength of the ocean, determined by the Keeper. A failure demands a Dodge roll to avoid being knocked over by the tiller, inflicting 1D3–1 points of damage.

H) Toolchests

The blacksmith and cooper’s tool chests are located outside the afterhouse. Resting on short skids and covered by tarpaulins, the starboard side is reserved for the cooper, and the larboard for the blacksmith. A row of wooden buckets hangs above each skid, and the area below is occupied by vegetable bins.

14. The Forecastle

Commonly abbreviated fo’c’s’le and pronounced “FOWK’sl,” the ship’s forecastle is the seaman’s home-away-from-home (49). Positioned inside the bow of the ship, the room is triangular in shape, surrounded by a double row of bunks on all three sides. (The Quiddity forecastle has 20 bunks.) The mattresses are stuffed with straw and corn-husks, thereby earning the traditional name of “donkey’s breakfast.” Lice and bedbugs are unfortunately common. Calico curtains hanging from each bunk provide the only privacy. The sailor’s sea-chests are placed on the floor in front of the bunks, where they double as seats. The forecastle is accessible through a companionway (48) located just in front of the foremast. The ladder touches down between two vertical columns: the shaft of the foremast piercing the compartment abaft the ladder, and a square column near the front of the forecastle. Designed to strengthen the windlass, this column supports a small wooden table where the men can socialize.

Fo’c’s’le Life

In some ways, the forecastle is little more than a floating tenement, and makes for some uncomfortable living during three long years at sea. Not only is it cramped, dark, and airless, the bow is the area of the ship most sensitive to motion—there’s a reason the captain sleeps at the stern! Over time, the forecastle acquires the odors one might expect: sweat, stale tobacco smoke, wet clothing, and general mustiness prevail. Food is lowered in buckets, and cockroaches tend to congregate at the strangest of places at seemingly random times. But still, the sailors make do the best they can, and attempt to enliven their home with music, card-playing, and sea-stories.

Development

As the voyage progresses, the forecastle gradually acquires a lived-in appearance: hanging clothing, strewn books and magazines, notices posted to the foremast, scrimshaw projects in various stages of completion—the typical bric-à-brac of a sailor’s life. Ricardo Reis hangs a polished steel mirror on the mast, and Jimmy Cabot turns his artistic prowess to graffiti, creating cheerfully pornographic displays along the wooden surfaces. Chess emerges as a popular diversion, with Veidt’s scrimshaw chessmen competing on a board carved directly into the table. As whales are tried-out, the compartment becomes increasingly more greasy. Uncharacteristically for a whaler, the Quiddity’s officers evince a genuine concern over the cleanliness of the forecastle. As Joab is fond of saying, “Men forced to live in filth like swine are likely to become as swine: there’s no greater Circe than a fo’c’s’le pigsty!” The men sardonically refer to the monthly forecastle scrubbings as “mucking the stable.”

15. Blubber Room

The blubber room (40) is a large compartment located between the forecastle and the steerage section. In order to provide more room for the hold below, the blubber room has an unfortunately low ceiling. Head injuries are common, and the men often work on their hands and knees. Hatches along the floor provide access to the hold.

Barry Moser, “Cutting blanket pieces into horse pieces.”

Barry Moser, “Cutting blanket pieces into horse pieces.”

Chopping Blubber

When a whale is being cut-in, the blanket pieces are lowered down the main hatch and curled on the blubber room floor. Each weighing over a ton, the blankets are reduced by half-naked men working in pairs: a pike-and-gaff man and a spademan. The gaff man hooks the blubber to prevent it from sliding on the oily, blood-soaked floor, while his partner climbs atop the blanket, chopping it into smaller “horse pieces” with his spade. As Melville writes, “If he cuts off one of his own toes, or one of his assistants’, would you be very much astonished?” Indeed, the Quiddity’s best spademan, Ao’nalu, is missing two of his toes. Ao’nalu’s gaff-man is Israel Reed, who’s rather fond of his toes, and maintains a constant state of caution Whipple refers to as “womanish.” Reed is also responsible for the blubber room’s most colorful graffiti. He’s created numerous anthropomorphic whales based on particular crewmen, along with witty cartoons playing on puns such as salt junk, horse piece, Bible leaves, nippers, and so on.

16. Steerage

The steerage section (23) is located between the blubber room and the cabin. It’s home to the “steerage gang,” the collective that includes the harpooneers and idlers. The steerage is divided into two main compartments, and is accessed through the “booby hatch” (24) in front of the midship shelter.

A) Boatsteerers’ Quarters

The larboard compartment contains four bunks, occupied by Quentin Shaw, Ulysses Dixon, Matty Shoe, and Quakaloo. Cramped but greatly preferrable to the forecastle, the compartment contains a narrow table and a rack of harpoons with whetstones, ropes, and spare poles.

B) Idlers’ Quarters

The starboard compartment is home to Seph Lovecraft, Leland Morgan, Stanley Ruch, Natty Weeks, and Thomas Plunkett. As the eldest sailor, Ruch is in charge of these quarters, and he keeps a tidy ship. A few Pennsylvania Dutch hex signs adorn the wall, and an apple crate fastened to Lovecraft’s bunk contains old books and magazines. Graffiti is strictly forbidden. Ruch sleeps very comfortably, under a quilt counterpane made by his mother Nellie. Each panel features colorful farm scenes.

C) Cabin Boy’s “Berth”

Benjamin Warnock sleeps on a hammock slung near the companionway. He’s afforded little privacy, and is available for sudden errands, noisome tasks, and shipboard pranks.

D) Officer’s Head

Located by the door to the cabin, this small privy is reserved for mates, boatsteerers, and idlers. Mounted above the door are the jaws of a great white shark, harpooned by Quentin Shaw and bleached to a snowy white. This has given rise to an assortment of euphemisms for using the privy—“Gotta feed the shark” being a typical example.

17. Cabin & Mess

The reasonably-spacious main cabin (13) is where the officers and steerage gang dine and socialize. It’s painted white with vermillion trim, and the skylight above keeps things bright and sunny. A metal cage hangs inside the skylight coaming, one of Loki’s many habitats. Three framed paintings are screwed into the bulkheads. The first is an exciting depiction of a whaling hunt, painted by Ichabod Allen in 1834; the second is a painting of the Quiddity, commissioned from New York artist Cornelius Wyatt; the third is a stormy portrait of Captain Seth Warnock, painted by nonother than Mary Brody in the “good old days.” It bears the inscription: “HE MAKETH A PATH TO SHINE AFTER HIM; ONE WOULD THINK THE DEEP TO BE HOARY.”

A) Mess Table

The mess table surrounds the mizzenmast housing, and is set with “fiddles”—brackets that hold the plates in place during heavy weather. Despite this, the table’s surface is scored from countless knives, which are frequently driven into the wood to keep dishes from sliding around. The benches have hinged backs, and are lowered when not in use to make more space. Each bench opens up to reveal additional storage.

B) Pantry

Accessed through the forward bulkhead, the narrow pantry contains the ship’s cookware, spices, and basic foodstuffs. The captain’s meals are often prepared here, sometimes with the assistance of the cabin boy.

C) Bookshelf

A bookshelf mounted on the starboard bulkhead holds fifty titles, black ribbons stretch across the spines to hold them in place. The collection is surprisingly worldly, and includes a Bible, Nathaniel Bowditch’s American Practical Navigator, several volumes of Shakespeare, Poe’s Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, Shelley’s Frankenstein, the Newgate Calendar of 1826 (“comprising interesting memoirs of the most notorious characters”), a battered copy of Redburn’s Nuka Hiva, George Walker’s The Three Spaniards (a shipboard favorite), the Jarvis Don Quixote, Dante’s Inferno, Chapman’s translations of Homer, a volume of Lord Byron, and a generous helping of Sir Walter Scott, Washington Irving, and James Fenimore Cooper. An untouched copy of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations has been filed upside-down. A pair of sensational anthologies show the most wear, those being: The Pirate’s Own Book: Authentic Narratives of the Most Celebrated Sea Robbers; and An Authentic Account of the Most Remarkable Events: Containing the Lives of the Most Noted Pirates and Piracies, Also, the Most Remarkable Shipwrecks and Disasters On the Seas. There’s also Captain Johnson’s trusty The Histories of the Pyrates, Vol. II. The most recent addition is The Life of Samuel Comstock, the Terrible Whaleman, published in 1840 by the mutineer’s own brother, William Comstock.

While the foremasthands have their own books in circulation (typically adventure stories and pornography), Captain Joab has instituted a shipboard library policy. Any man, even the lowliest forecastle jack, may request to borrow a single book. This request is made through the steward, Thomas Plunkett. However, if the book is returned in an unsatisfactory condition, the borrower is docked the cost of the volume and denied further use of the library. In order to facilitate this open-minded policy, Joab has ordered Plunkett to post a list of titles in the forecastle. Of all the sailors, Owen Love, Israel Reed, Zimri Folger, Isaac Townshend, and James Cabot take the most advantage of the policy. The surly Plunkett is less than thrilled with his added responsibilities.

D) Entrances & Exits

Being the social hub of the Quiddity, the cabin sports numerous entrances and exits. These differ a bit from the Lagoda diagram, and follow the arrangement found on the Charles W. Morgan. A narrow door on the forward bulkhead leads to the steerage section. This door can be locked from the cabin to bar entrance during the officers’ mealtimes. The larboard bulkhead contains two doors, one to the mates’ quarters and one to the first mate’s stateroom. The staircase to the afterhouse is located at the larboard aft—the cabin companionway (4) described above. The captain’s cabin is accessed through a door on the aft bulkhead. All of these locations are details further below. Unlike the steerage quarters, all rooms connected to the cabin feature portholes, including the pantry.

18. Mates’ Quarters

The mates’ quarters (18) are occupied by Mr. Joseph Coffin and Mr. P.H. Whipple, although Stanley Ruch has added an extra bunk for Dr. Montgomery Lowell. While Whipple’s a bit of a slob, the player characters are welcome to furnish the room as they see fit. The bulk of Lowell’s scientific equipment is stored in the captain’s cabin.

19. First Mate’s Stateroom

Located abaft the mates’ quarters, the stateroom of Mr. William Pynchon is a model of decorum. Painted white with vermillion trim, the walls are decorated with a daguerreotype of the House of the Seven Gables and a painting of Sag Harbor. A small desk illuminated by a polished lantern holds the ship’s log, Pynchon’s stylized whaling stamps, and a set of steel Atwood pens in a Japanned box. Although Pynchon is a voracious reader, his stateroom contains only a handful of books: a ragged first-edition Bowditch, a modest Bible, Lucretius’ De rerum natura, a collection of Aristophanes plays, an 1827 printing of William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and a battered copy of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound.

20. Captain’s Cabin

The Quiddity boasts a beautiful captain’s cabin, furnished from dark, polished wood and sporting a Persian rug. It’s larger than most whaler’s cabins, and speaks of the Quiddity’s origins as a merchantman. The skylight and stern windows offer generous amounts of sunlight, and brass lanterns provide ample illumination during evening hours. The traditional captain’s couch occupies the stern, its plush red panels perfect for napping, as Joab is wont to do—he disdains the gimbaled bed in his stateroom. Mounted above the couch are two Kentucky rifles, both kept immaculately clean. A blunderbuss hangs below the rifles. Set into the bench supporting the couch are three paneled doors; within the captain keeps various supplies, including extra lanterns and flints, powder & shot for the firearms, and twenty-three bottles of quality red wine. Lowell’s scientific supplies are stored here as well.

The larboard bulkhead features a mahogany bookcase holding the captain’s navigational texts, maps, and his own personal library. The starboard bulkhead is adorned with a painting of Kingsport Head at sunset, the western rocks aglow with bloody twilight and the ocean engulfed in blackness. A lone ship occupies the horizon, its flaming trypots illuminating a serpentine plume of smoke before vanishing in gloom. The frame reveals the title: Starless and Bible Black. A fearsome harpoon is mounted below the painting. Beaten back into shape and refitted to its original pole, this was the iron Joab used to harpoon his first whale onboard the Phebe Ann in 1818. A brass plaque contains an inscription:

AND WHAT I SHOULD BE, ALL BUT LESS THAN HE

WHOM THUNDER HATH MADE GREATER?

A) Joab’s Desk

Joab’s desk is positioned beneath the skylight, affording an easy view of the “transparent” compass suspended above. A handsome and sturdy desk, it boasts an expensive globe laid with colored enamels, an elaborate writing set, a brass desk-lamp powered by spermaceti candles, a stunning chess set, and a wooden perch where Loki squawks contentedly while the captain works. (Plunkett is less happy about cleaning the bird’s droppings.) The desk has three drawers. The upper two contain stationery, stamps, a magnifying glass, and maps. The bottom drawer is locked.

Joab’s Chess Set

Joab’s expensive chess set was custom-made in Innsmouth. Black is represented by whalers carved from stained wood, with seamen as pawns, a blacksmith and cooper as rooks, harpooneers as knights, mates as bishops, a chief mate as queen, and a salty captain as king. White is represented by scrimshaw sea-creatures carved from whalebone, with flying-fish as pawns, walruses as rooks, narwhals as knights, squid as bishops, a mermaid as queen, and a sperm whale as king. The mermaid is an exact replica of Cunny Quid. When not in use, the set is stored in a leather case. Joab occasionally allows the officers to use it, but they must play in the main cabin.

B) The Firearms

Joab’s Kentucky rifles are works of art, hand-crafted by a Pennsylvania gunsmith and further engraved by Valentine & Howell. The wood is etched with nautical themes, and the stock features a brass patchbox inscribed with a compass rose. The hexagonal barrels are made from Damascus steel. It’s expressly forbidden for anyone except Joab to even touch the rifles. Less ornate is the ancient blunderbuss hanging below the rifles—the very piece Joab used as a crutch when he emerged from his delirium, it still bears a stain where it thumped Watts across the head.

C) The Bookcase

Joab’s library includes Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Virgil, Cicero, Ovid, Plutarch, and Dante; the collected works of Shakespeare; Kit Marlowe’s Faust; selected volumes of Milton, Pope, and Dryden; Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; and Goethe’s Faust, which he’s currently reading for the first time, struggling valiantly through the German. There’s also several volumes of the second Panckoucke edition of Napoleon’s Description de l’Égypte. Although Joab disdains the “effete” Romantics, he can quote most of Paradise Lost by heart, and King Lear moves him to tears. Two recent acquisitions have been spending more time on Joab’s desk than his bookshelf. The first is William Comstock’s Voyage to the Pacific, which tells of the author’s deadly encounter with Mocha Dick onboard the Nantucket whaler General S. The second is Jeremiah Reynolds’ pamphlet Mocha Dick or The White Whale of the Pacific. Although Reynolds claims to have met the man who killed Mocha Dick in 1829, Joab contemptuously overlooks this ridiculous assertion.

D) The Slop Chest

A trunk near the bookcase serves as the Quiddity’s slop chest, a kind of “company store” where the crew may purchase tobacco, spare clothing, coats, mittens, razors, knives, and anything else they might have lost or forgotten to pack. Items purchased from the slop chest are recorded on a ledger maintained by the third mate. The price is significantly marked up from shore value, and deducted from the sailor’s lay at the end of the voyage.

E) Captain’s Stateroom

Joab’s personal stateroom is located between the main cabin and the starboard hull, and is accessible through a door on the starboard side of the captain’s cabin. It features a sunken bed on gimbals, a closet and a dresser, a washstand and mirror, and access to a private head. A painting of the Janus is screwed into the wall near the porthole above the bed. It shows the ship at dawn near a tropical island, its rigging aglow with beams of golden light.

E) Entering the Cabin

The door to the captain’s cabin is usually closed. All comers must knock and receive permission to enter. This includes Pynchon and Dr. Lowell, who is authorized to use the cabin two hours each day. When Joab and Lowell are away from the cabin, it’s kept locked, and only Joab and Plunkett have keys.

21. The Hold

The ship’s hold is accessible through a grating in the steerage section and a large hatch in the blubber room. Damp and stuffy, the hold is populated by the usual complement of rats and cockroaches. Everything is stored in casks, even spare sails—otherwise the rats chew through it all. As stores and provisions are consumed, the emptied casks are filled with whale oil. Casks are stored on their sides and stacked into two tiers, the “riders” staggered across the grooves formed by the “ground” tier below. The spaces between stowed casks are called “cuntlines,” an expression fairly obvious in origin. The casks are stabilized by wedges of cordwood called “dunnage.” Wooden railings or “pen boards” may be slotted in place throughout the hold to provide additional support. In the tropics, the hold is pumped full of seawater every few days, then drained the following day. Not only does this prevent shrinkage, it keeps vermin under control and helps monitor potential leakage—careful watch is kept on how much oil is mixed with the outgoing water. At the bottom of the hold is the ballast, a sturdy mixture of good Kingsport stone.

A) Provisions

The hold contains most of the provisions for the outward leg of the journey. The supplies include, but are not limited to: 100 barrels of salt beef, 100 barrels of salt pork, 130 barrels of flour, 20 barrels of dried fruit, 2000 gallons of molasses, 1120 pounds of coffee, 3000 pounds of tobacco, 2200 cigars, 38 pecks of salt, 170 pounds of nutmeg, 35 pounds of ginger, 320 pounds of tea, 2 complete suits of sails, 36 pairs of suspenders, 850 buttons, and 175 harpoons. The hold also contains casks of water. The ground-tier casks are filled with saltwater for additional ballast, while the riders contain fresh water for drinking.

Barrels of Fun!

A cask is a cylindrical container used for storage. It’s composed of wooden staves held together by iron hoops. The flat end is called the “head.” The edge of the cask that extends past the head is the “chine.” (Modern usage has transformed this into “chime.”) A cask containing a liquid is tapped through a hole called a “bung.” Casks are longer than they are wide, and have a bulge in the middle. This bulge is called the “bilge,” and makes the cask easier to manipulate that a cylindrical “drum.” When on its side, a cask may be rolled or rotated, and a single seaman may tip the cask upright by a series of increasing wobbles. Lighter casks are lifted using an iron “chine hook,” a hinged clamp that grips the chines and offers a convenient handle. Heavier casks are hoisted using light tackles called “burtons.”

Although the word “barrel” is often used interchangeably with cask, a barrel denotes a cask of a certain size. The standard barrel of whale oil contains approximately 32 gallons. A whaleship carried casks of many sizes, storing everything from molasses to sails. The following list is English in origin, and there are many variations: liquids vs. dry goods, U.S. vs. Imperial measurements, etc. But this should do fine for the Quiddity:

| Cask | Capacity in gallons |

| Firkin | 5 |

| Keg or breaker | 10 |

| Barrel | 32 |

| Tierce | 42 |

| Hogshead | 63 |

| Puncheon | 84 |

| Pipe or butt | 126 |

| Tun | 252 |

B) Anchor Locker

Commonly referred to as the “chain pit,” the anchor locker is a rectangular cabinet housing the anchor cables. It’s located abaft the bilge pump, and extends from the hold up through the blubber room.

C) Bilge

For all practical purposes, the bilge is the lowest part of the hull, designed to collect water from the inevitable leaks common to all wooden ships. Also, heavy seas and rain contribute their fair share. A byword for filthy waste, “bilgewater” is an unpleasant blend of fouled water, oil, whale blood, pitch, urine, and rat droppings. It’s pumped out regularly using the pump on deck. Because the bilge is divided by the keel, the plural is sometimes used, such as, “The bilges are full.” The bilge is accessible through hatches in the hold.

Keepers and players interested in learning more about whaling ships and sailing may find dozens of resources online. However, White Leviathan may be enjoyed without knowing the difference between tacking and wearing, or what it means to stow dunnage in the larboard cuntlines. If a group is more “Pirates of the Caribbean” than “Master and Commander,” that’s totally fine, and you can always skate by with nonsensical jargon: “Make sure you reef the scuppers before the ratlin’ slips the hawser, ye scurvy dogs!” Just remember, a failed Seamanship roll always earns the scorn of one’s shipmates.

Sources & Notes

Four books have been particular useful in creating the Quiddity, all of which include excellent illustrations: Clifford W. Ashley’s The Yankee Whaler (Dover 1926), A.B.C. Whipple’s The Whalers (Time-Life 1979), John F. Leavitt’s The Charles W. Morgan (Mystic Seaport Museum 1998), and Ben Lankford’s Instruction Manual: New Bedford Whaling Bark Charles W. Morgan (Model Shipways 1997). Another fantastic resource is John Fleming’s Charles W. Morgan Model Ship Site. An exhaustive record of Fleming’s painstaking reconstruction of a miniature whaling ship, this blog offers a master course in model shipbuilding. There’s also the 1922 silent film Down to the Sea in Ships, which features the Charles W. Morgan and the Wanderer; although the whaling sequences were filmed on a fishing schooner tricked out as a whaler. Also recommended is the video, “How to Sail a Full-Rigged-Ship—The Sørlandet,” which has an unbeatable opening theme! And finally, I’d like to thank Nathan Rumney and Mary K. Bercaw-Edwards of Mystic Seaport, who helped me hammer down numerous minute details. Any mistakes and inaccuracies are my own.

Historical Notes

The Quiddity is a fictional ship, much like the Pequod. As such, I’ve taken artistic liberties to make it more colorful and interesting than its historical counterparts. Most whaling vessels were filthy, ramshackle affairs designed to maximize profit—they wouldn’t feature brass bands engraved with constellations or commissioned works of art! However, aside from such embellishments, I tried to make the Quiddity as authentic as possible. Keepers are welcome to make any alterations that better suit their campaign, from re-rigging the masts to installing a crow’s nest. The important thing is to have fun, and every playthrough of White Leviathan should feature a unique version of the Quiddity!

Images

Much thanks to the late John Henry Batchelor, whose wonderful diagram of the Lagoda has been borrowed to illustrate the Quiddity. The etching at the top of the page is based on Sir Oswald Brierly’s 1876 watercolor, South Sea Whalers Boiling Blubber. The photograph of the Charles W. Morgan at dock is by Edwin Hale Lincoln; I made Photoshop alterations to banish a few twentieth-century intrusions. The photograph of the Salmon P. Chase is from the Library of Congress; the labels are my own addition. The mast diagram and the illustration of belaying pins were borrowed from Wikimedia Commons. The illustrations for “tacking” and “wearing” are courtesy of Tim Migaki, and were derived from R.G. Grant’s Battle at Sea. The photographs of the Morgan’s deck are by Daryl Carpenter, Ben Lankford, and myself. The photo of the tryworks is from Cutting In a Whale: A Series of Twenty-Five Photographs, published in 1903 by H.S. Hutchinson & Company. Barry Moser’s illustration of the blubber room is from the magnificent 1981 UCP Moby-Dick—my favorite of the many illustrated editions of Melville’s novel. I found the Pennsylvania Dutch hex signs online. Both were uncredited, so I claim them as my birthright! (Ya, Ich kann’ bissel Deitsch schwetze! Stanley der Schreiner iss mei Graempaepp.)

White Leviathan > The Quiddity and Whaling

[Back to Quiddity (Keeper’s Version) | White Leviathan TOC | Forward to Life on a Whaling Ship]

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 13 March 2022

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

White Leviathan PDF: [TBD]