Kingsport Cult

- At August 22, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Call of Cthulhu

0

0

It is the night-black Massachusetts legendry which packs the really macabre ‘kick’… for certainly, no one can deny the existence of a profoundly morbid streak in the Puritan imagination. The very pre-ponderance of passionately pious men in the colony was virtually an assurance of unnatural crime; insomuch as psychology now proves the religious instinct to be a form of transmuted eroticism precisely parallel to the transmutations in other directions which respectively produce such things as sadism, hallucination, melancholia, and other mental morbidities. Bunch together a group of people deliberately chosen for strong religious feelings, and you have a practical guarantee of dark morbidities expressed in crime, perversion, and insanity.

—H.P. Lovecraft, letter to Robert E. Howard, 4 October 1930

Introduction

The Kingsport Cult was introduced by H.P. Lovecraft in his 1923 story, “The Festival.” Unnamed in the story, the cult was depicted as an order of ancient sorcerers in possession of the Necronomicon and worshipping a Green Flame below the crypts of the Church on Central Hill. Through communion with this Green Flame, the elder cultists achieved longevity by gradually replacing their bodies with vermin. They concealed this horror using loose clothing and waxen masks. In Chaosium’s Kingsport: The City In the Mists, Kevin Ross provided a history of the cult, tracing them back to the Channel Islands and weaving a coherent narrative of their rise and fall. Among other details, the cult was dubbed the “Kingsport Cult,” the church was identified as a Congregational Church, and the Green Flame was named “Tulzscha.” White Leviathan significantly expands the history of the Kingsport Cult and the Green Flame. The following chronicle builds on Lovecraft and Ross, tracing the cult back to its medieval origins and granting it renewed vigor in the mid-nineteenth century.

Kingsport Cult: Founding and Persecution (1180–1722)

If somebody brings up the Templars, he’s almost always a lunatic.

—Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum

The Green Flame may be ancient in origin and global in reach, but the Kingsport Cult is rooted in the Cathar heresies of southern France. As Gnostics, the Cathars believed in a twofold deity: the Invisible Father of the New Testament, and the Fallen Demiurge of the Old Testament. Known as Rex Mundi, or “King of the World,” this latter figure was often conflated with Satan. Once devoutly loyal to the Invisible Father, the Demiurge rebelled and created the world of matter—our world. The Cathars believed that humans are angels who have become engrossed, or trapped, in this material world. Until we break this prison and become beings of pure energy, we are doomed to an endless cycle of reincarnation.

Montségur

While most Cathars peacefully subscribed to traditional Gnostic principles, one sect sought immortality—a sacrament they called Consolamentum—through communion with the Green Flame. Calling themselves the Bons pêcheurs de la flamme viridienne, or the Good Fishermen of the Viridian Flame, they were founded in 1180 by Estienne Mordant, a Templar who brought the Green Flame to Languedoc from Byzantine Anatolia. Although no records of his travels exist, Mordant is thought to have been influenced by the Bogomils, particularly a sect that worshipped the Green Flame under the name of Tulzscha, and associated it with Thoth, the Egyptian god of magic. Mordant’s original followers were known as the Pauvres chevaliers de la flamme viridienne, or the Poor Knights of the Viridian Flame, but after settling in Montségur, he changed their name to Bons pêcheurs. Seeding the Green Flame in the warrens below Montségur’s mountainous pog, the cult developed beliefs so heretical they were quickly shunned by other Cathars. (Interestingly, the word pog is derived from the Latin word for “hill,” the origin of the word “pagan.”)

It was not merely their devotion to the Green Flame that branded them apostates. The Bons pêcheurs inverted the Cathar hierarchy, placing the Fallen Demiurge above the Invisible Father and directing their worship to Rex Mundi. They associated the Demiurge with Dagon, the god of the Philistines who was dismembered before the Ark of the Covenant. Jesus Christ was not revered as the Redeemer, but Judas Iscariot, who accepted the burden of becoming the most reviled figure in history. While most Cathars embraced an ascetic lifestyle of pescetarianism and strict abstinence, the Bons pêcheurs wallowed in the material world. Rejecting the Invisible Father as a barren god of sterility and rigid laws, they indulged in debauched orgies around the Green Flame, their worshippers absorbing its cold radiance as the Eucharist of Dagon. Communicants would bleed into a communal chalice and swear fealty to the cult, then Mordant would then place a living worm in their mouths and offer them a drink of blood. The Bons pêcheurs believed that as the body became increasingly consumed by the filth of creation, the soul became paradoxically more pure. (Despite the charges of sodomy and coprophagia later leveled at the Templars, Mordant did not perform the “shameful kiss,” and the consumption of human excrement was only practiced among the most debased cultists.) Once the body had reached Integrum Corruptionem—complete vermification—Consolamentum was attained: the flesh was sloughed off and the soul liberated, flying upward to join the angelic orders. Eventually such angels would be powerful enough to restore Rex Mundi to his shattered throne. The balance finally restored between the spiritual and material worlds, a New Aeon would dawn; literal heaven on earth.

From Montségur to the Channel Islands

In 1212 the Bons pêcheurs were exiled from Montségur by Guilhabert de Castres, the Cathar theologian and soon-to-be bishop. They relocated sixty miles east to the Mediterranean coast, founding a small community called Saint-Iscariot (present-day Saint-Nazaire in the Pyrénées-Orientales). In 1244 the Albigensian Crusade crushed the Cathars at Montségur, and the Inquisition burned 200 heretics under the ramparts of the castle—perhaps not coincidentally, above the very cavern where the Green Flame once resided. Seeing the writing on the wall, the Bons pêcheurs fled north, settling in Provins and thence to Normandy. In the fifteenth century the cult spread to the Channel Islands, where it acquired Anglo-Saxon influences. It was here that some adherents began referring to themselves as the “Covenant of the Green Flame.”

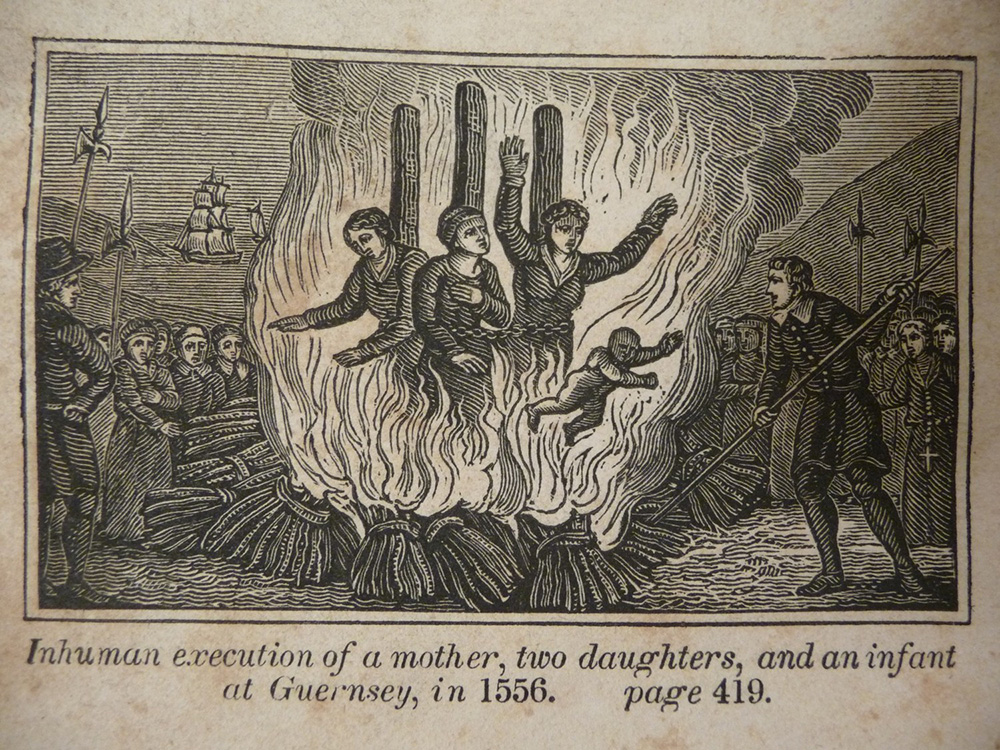

By the early sixteenth century, the Bons pêcheurs had strayed considerably from their Gnostic origins, and were devolving into a simple witch cult. Even the word “Covenant” was shortened to “coven.” The Jersey coven had replaced Dagon with Baphomet, while on Alderney the Bon pêcheurs were indistinguishable from pagan witchcraft. Only the Guernsey coven maintained the Old Ways. Guided by an energetic woman named Bertrane Quaripel, a direct descendent of Estienne Mordant, the coven communed with the Green Flame at La Catioroc and maintained the Cathar eucharist.

The Covenant was introduced to the Mythos in 1595, when Bertrane Quaripel acquired an incomplete copy of John Dee’s Necronomicon. She believed its strange deities were culled from the antiquated religions of Babylon and Egypt, and referred to their worship as l’Ancienne Religion, or “The Old Religion,” a name still used by the Bons pêcheurs to describe the Mythos. To the Guernsey Coven, Cthulhu was just another version of Rex Mundi, and was simply conflated with Dagon. When Quaripel’s granddaughter Perotine Cauchés used the Necronomicon to summon a Byakhee, the startling appearance of the familier was likened to the demons of Revelation; further proof that l’Ancienne Religion and the Coven’s debased Catharism shared the same essential roots.

As the seventeenth century lurched towards the British Civil Wars and Cromwell’s grim Commonwealth, the Channel Islands were gripped by increasing Presbyterian zeal. Soon the Covenant found the banked fires of Inquisition were being eagerly rekindled by Protestants. As more witches were consigned to the flames—typically dropped into a bonfire at the end of a noose—the Bons pêcheurs escaped to the New World, settling in Newfoundland, New Jersey, and New England. In 1639 Kingsport was established in Massachusetts, with Innsmouth following in 1643.

Kingsport

Among Kingsport’s founders were three influential witches: Perotine Cauchés, already 138 years old; Denys de Quetivel, the most formidable of the Jersey wizards; and Malachi Hogg, a pirate captain from Sark. Originally not a Bons pêcheur, Hogg—the spelling would later change to Hoag—embraced the Covenant after he was falsely accused of witchcraft in Guernsey, the bailiff having cut off his ear and whipped him in the public square. The Green Flame was seeded in the caverns below Kingsport’s Central Hill, and Fishermen’s Chapel was erected in the woods near Nanepashemet Creek.

After a half-century of tranquility, witchcraft hysteria finally caught up with the Covenant in 1692. Denys de Quetivelwas hanged with twelve other “witches,” six of whom were innocents swept up in the righteous frenzy. After a brief resurgence under the charismatic Father Rufus Cheever, the Covenant was dealt another blow in 1722, when Kingsport mayor Eben Hall arrested the “St. Michael’s witches” after their Yuletide ritual. Nobody was executed, but thirteen cultists committed suicide on the Gravesend prison hulk. (See “Brief History of Kingsport” in Chapter 1 for details of these events.)

Expanded Horizons (1723–1762)

It was around this time that Abner Ezekiel Hoag enters the picture. One of the witches hanged in 1692 was a Kingsporter named Exekiel Diamond. His daughter was a midwife named Phebe Ann, who fled to New Plymouth to escape her father’s fate. There, she married a Congregationalist printer named Isaiah Hoag, the grandson of Kingsport founder Malachi Hogg and the nephew of hanged witch Lobelia Tuttle. Isaiah was renowned for his brave stand against the witchcraft hysteria sweeping the colonies. An ardent pamphleteer, he pleaded with New Englanders to show greater compassion, humility, and temperance in their feverish embrace of these “reckless” trials. His pamphlets dared to question the motives of accusers, upheld the good name of Salem’s John Alden, and even called upon Britain to forcibly intervene. It went over about as well as one might expect, and Isaiah and Phebe Ann were driven from town. They relocated in Arkham in 1696. Isaiah abandoned printing for trading, and shrewdly invested in Kingsport’s burgeoning shipping industry. Abner Ezekiel Hoag, their only child, arrived a year later. Somewhat portentously, he was born in the caul.

Never a member of the Bons pêcheurs, Isaiah’s disdain for Puritan sanctimony caused him to turn a blind eye to the genuine witches in his midst. Nor did he believe in “hocus pocus, dancing goats, and general black cattery.” His son, however, was a different story. By the age of thirteen, Abner was already at sea, bragging about the “witchcraft” in his blood and proving himself quite the young hellion. In 1712, Abner was introduced to the Marshes of Innsmouth, where he first learned about the Necronomicon and the Kingsport Cult. Intrigued by the tales of l’Ancienne Religion, he was even more captivated by young Bathsheba Marsh. They only slept together once, but it was enough. Forced into marriage at the age of fifteen, Abner remained ashore just long enough to welcome his daughter Nerissa. He returned a year later and sired a son, Ethan, before shipping out on a Tuttle merchantman. After several years of Hoag’s pointed absence, the Marshes raised the children in Innsmouth without his further involvement.

The Ponape Scripture

Isaiah and Phebe Ann Hoag died of measles in 1713. Before he passed, Isaiah entrusted his business interests to his partner Mayhew Corben, whose son Douglas was Abner’s best friend. While too young and impulsive to be “lashed to a counting house desk,” Abner and Douglas proved very capable leaders in the rum-and-copra trade. Quickly gaining command of their own ships, they were formally inducted into the Covenant in 1725, part of a new wave of initiates in the wake of Mayor Hall’s arrests. Both would soon discover evidence of Green Flame worship outside of New England; Captain Corben in the West Indies, and Captain Hoag on Ascension Island in the Pacific. Although Mayor Hall ordered Corben’s Hellene sunk outside of Kingsport, Hoag and the Ponape Scripture made it safely home in 1735. His discovery created quite a stir among the surviving members of the Covenant. Here was a manuscript that described the Green Flame, and provided evidence of its worship beyond the Bons pêcheurs. It also hinted at some older and more complete text, a history of the Green Flame and its arcane powers that predated the Necronomicon.

The R’lyeh Text

In the years following Douglas Corben’s death, Abner Hoag befriended his cousin Isaiah Tuttle, a bookish young officer who’d served under Hoag before commanding his own ship. A promising scion of the Tuttle shipbuilding clan, Isaiah’s branch of the family became involved in the Kingsport Cult after his grandfather James Tuttle married Malachi’s daughter, Lobelia Hogg. (Both James and Lobelia were hanged in 1692.)

Using information provided by Hoag, Captain Tuttle sailed to the Caroline Islands and followed a trail of clues westward. In 1756 he discovered a copy of the R’lyeh Text near Angkor Wat. Written in Middle Khmer on a series of palm-leaf manuscripts, the book was accompanied by mysterious diagrams inscribed on plates of lacquered wood. Returning to Kingsport with a Cambodian translator named Lon Dara, Isaiah spent the next few years studying its secrets and regrouping the Bons pêcheurs. He was aided by his wife Rowena, a self-taught “antiquarian” from Kingsport’s eccentric Orne family. Learning about the existence of the Ancestors, the trio connected Dagon and the Green Flame with K’th-oan-esh-el and the K’th-thyalei. The R’lyeh Text also shed light on the Necronomicon, revealing a more coherent mythology behind Cthulhu and his minions. After half a millennia of Gnosticism and witchcraft, the Bons pêcheurs became a true Mythos cult.

In 1762 Bathsheba Hoag died, and Abner was reunited with her family in Innsmouth. By that time, Nerissa had become a mother of her own, marrying her cousin Jeremy and giving birth to a son named Randall Marsh. (His daughter Flora would later move to Arkham and marry Charles Warnock. Their son Seth Warnock would be a future member of the Covenant and Captain Joab’s closest friend.) Ethan had also married, settling down in Arkham with a respectable Christian woman named Bertha Lapham. Having broken ties with his “heathenish” family, Ethan Hoag attended the funeral alone, departing Innsmouth the moment his mother was in the ground.

Bathsheba’s funeral provided the opportunity for an intermural exchange of knowledge, and both cults developed plans for expanding their understanding of Dagon. Although neither group realized it at the time, they would eventually diverge sharply in their beliefs, with Kingsport devoting itself to the Green Flame, and Innsmouth seeking prosperity through the practical worship of Dagon.

The Tuttle/Black Macy Union (1763-1818)

“Woman, go below and seek thy God. I fear not the witches on earth or the devils in hell!”

—Thomas Macy, founder of Nantucket, to his wife during a storm at sea

Soon after he returned to Kingsport, Abner Hoag heard rumors that a small coven in Nantucket was quietly practicing witchcraft. Now in his sixties, Hoag traveled to Nantucket to meet this group, a tangled knot of Macys, Coffins, and Husseys at the fringe of Quaker society. Although the rumors were true, their “witchcraft” amounted to little more than esoteric family traditions carried across the sea from Southwest England. The so-called “Black Macys” believed their forefathers had learned black magic from the Nephilim, fallen angels trapped in the material world. They had no written scriptures, and sadly for Hoag, their oral tradition was a confused muddle of English folklore and Elizabethan occultism. However, at the roots of this farrago was something more authentic, and a few of their “fallen angels” bore names from the Necronomicon. They were also familiar with the Voorish sign, a “blessing” learned by their ancestors in their dreams. Hoag absorbed what he could from the dubious Quakers, and in return taught them about the Covenant.

Mary Coffin Macy

In a case of history repeating itself, Hoag again became enamored with the daughter of his host. Unlike Bathsheba Marsh, who knew little about her family’s blasphemous practices, Mary Coffin Macy was a Black Macy through-and-through. She was born in 1735 during rare appearance of the northern lights. Her father was Captain Peleg Coffin, the grandson of Nantucket founder Tristram Coffin, a man who spoke to angels in his dreams. Her mother was Delilah Hussey, a self-proclaimed “changeling” disowned after her parents found her dancing naked in the surf. Shortly after Mary was born, Peleg Coffin was killed during an attempted mutiny off the coast of the Azores. In 1740, Delilah married her husband’s best friend, Zachary Macy. A descendant of Nantucket founder Thomas Macy, “Black Zack” had been Captain Coffin’s protégé, and raised his friend’s daughter as his own. Their considerable wealth shielded the family from harm, but even so, the “Black Macys” were generally shunned by polite company.

Although Mary was thirty-eight years younger than Abner, his preternaturally youthful appearance was part of his appeal—Mary and her family wanted access to the Covenant’s occult powers. Zachary and Delilah enthusiastically blessed the union, and Mary and Abner were married at sea by Captain Isaiah Tuttle. In 1764, Barzillai was born. Knowing that “Coffin” was a more fortuitous name in Nantucket, Abner insisted his son be given Mary’s surname. Two years later, Hoag sailed for England to acquire the Cthaat Aquadingen. He never arrived, his ship lost off the coast of Ireland.

Hoag’s death was a blow to both clans, but life carried on. Following in his father’s footsteps, young Barzillai Coffin went to sea at the age of thirteen. By the age of twenty-two, he was master of his own whaling ship. Mary never had the chance to extend her life through the Green Flame. In 1783, she was found dead in a pigsty, naked and straddling a broom. Zachary blamed her death on a “nervous heart,” but everyone knew she had poisoned herself with belladonna while attempting to fly.

Meanwhile back in Kingsport, study of the R’lyeh Text continued. Although Lon Dara had returned to Cambodia before the Revolution, with the help of his extensive notes and Rowena’s opium-induced insights, the Tuttles had translated much of the manuscript, and even worked out some of its mysterious codes and diagrams. In 1787 they presented their progress to their fellow Bons pêcheurs. Now the de facto leaders of the cult, Isaiah and Rowena announced the Covenant’s next move—to locate the mysterious islands mentioned in the Ponape Scripture and confirmed by the R’lyeh Text. They believed these islands contained relics of ineffable power: the Head and Hands of Dagon. To accomplish this task, they’d need ships capable of wandering the Pacific Ocean. And thanks to Abner Hoag’s son in Nantucket, they had the perfect allies.

Whaling Comes to Kingsport

In 1788 Isaiah and Rowena’s son, Franklin Tuttle, was dispatched to Nantucket to learn the secrets of whaling from the Black Macys. He brought along his wife Eliza Illsley and their daughter Anna. A charming young woman of seventeen, Anna was immediately smitten with Zachary’s grandson, a dashing captain named Absalom.

The marriage of Anna Tuttle and Absalom Macy was celebrated on June 21, 1789 at the old Fishermen’s Chapel in Kingsport. The happy couple returned to Nantucket, but their union was the last straw for the god-fearing Quaker community. It was one thing to believe in fairy magic and talking angels; it was another to marry a Kingsport coof and take business off the island. The Black Macys went from being discreetly shunned to openly reviled.

After a few months of negotiation, Zachary and Isaiah decided to merge more than their bloodlines; they would become a single business guided by one religion. In 1790 the Black Macys relocated to Kingsport, completing a union that began in 1762. They brought along their intimate knowledge of whaling. It was the perfect solution to the Covenant’s problem. Not only could they openly explore the Pacific, they’d make a great deal of money in the process! The first Kingsport whaling ship was launched in 1792. Christened the Anna, she was captained by Barzillai Coffin, and made her first successful cruise along the coast of Chile. Believing it best to operate as openly as possible, the families shared their resources with other Kingsport merchants and builders. Soon Kingsport was floating several whaling vessels, most of them unconnected to the Bons pêcheurs.

Return of the Prodigal Son

In 1799, the Covenant was shocked by the return of Abner Ezekiel Hoag. Over 100 years old but not looking a day over 70, the Covenant’s oldest member had spent the last thirty-three years roaming the planet and studying the Green Flame. He’d been to Ireland, Cornwall, England, the Channel Islands, Provins, Languedoc, Lombardy, Rome, Crete, Macedonia, Anatolia, and even the Holy Land. And now more than ever, Hoag was convinced that Dagon’s return was immanent; and the instrument of that return would the Bons pêcheurs. Declining the Tuttles’ offer to assume leadership of the Covenant, Hoag retired to his crumbling residence on Green Lane and devoted himself to studying the R’lyeh Text.

The New Century

The end of the eighteenth century saw a turnover in Covenant membership as the old guard stepped down, died off, or faded away. Franklin Tuttle went mad, and was confined to live his remaining years in the attic of Tuttle Manor. Black Zack Macy and his son Ezekiel, Absalom’s father, died in the Tempest of 1800, killed when the storm collapsed their home on Stratton Point. Rowena Tuttle retired from Covenant politics to focus on translating Perotine Cauchés’ grimoire, Le livre de la méchanceté. There were material setbacks as well. The War of 1812 sank three whaling ships and dealt a financial blow to the Tuttle empire. Fortunately, the family’s investments in the shipbuilding industry allowed them to weather a crisis that nearly wrecked the Kingsport economy.

These losses were balanced by an influx of new blood and fresh ideas. New York lawyer Benjamin Sleet brought his legal acumen to the Bons pêcheurs, while Franklin and Eliza’s son Fletcher Tuttle exchanged traditional witchcraft for financial wizardry. On account of her husband’s madness, Eliza was discreetly allowed to become Benjamin Sleet’s mistress. Although she died during childbirth, her son Gideon Sleet became one of the Covenant’s most enterprising sea captains. He was joined by Ezra Coffin, Barzillai’s oldest son; and Seth Warnock, Abner Hoag’s great-great grandson through his first marriage to Bathsheba Marsh.

However, the Covenant’s most formidable new initiate was Judge Return-to-Dust Whicher. An intellectual in the mold of Perotine Cauchés and Rowena Tuttle, Judge Whicher was a Puritan theologian who became one of Kingsport’s most dynamic Selectmen. In 1809 Whicher accomplished what Abner Hoag could not: he returned from England with a copy of the Cthaat Aquadingen. Forming an unlikely alliance with the reclusive Hoag, Whicher helped modernize the Covenant, shedding the trappings of witchcraft accumulated during the previous centuries and rebuilding on contemporary Masonic foundations. In 1811, Sleet, Baker & Blood was founded to manage the Covenant’s legal affairs. The Bons pêcheurs renaissance culminated in 1818 with the announcement of the Great Work, the Covenant’s plan to resurrect Dagon. (See “Background Part 3” for details.)

The Contemporary Covenant (1819-1844)

Today’s Covenant is smarter and more organized than the witch cult broken by Eben Hall, and can even afford to laugh at the grotesque public depictions of “Old Mother Cawches” and the “diabolical” Father Cheever. Ironically, the greatest benefit to the contemporary Covenant has been modernity itself: nineteenth-century America has few believers in sorcery, and even most religious leaders regard the witch hunts of the colonial era with shame and disgust. As Professor Van Helsing remarks in the 1931 film Dracula—“The strength of the vampire is that people will not believe in him!”

Current Leadership

The Covenant is still led by Isaiah Tuttle, a 136-year-old mass of worms driven by an unholy will to complete the Great Work. Although he’s neither as ancient nor knowledgeable as Abner Ezekiel Hoag, the Covenant patriarch refrains from politics, and is content to quietly “advise” until the Day of Resurrection is at hand. Rowena Tuttle declined the Rite of Consolamentum, but remains alive at 119, and continues her lifelong project to completely decipher the R’lyeh Text. After this venerable trio comes Absalom Macy, 84 years old but looking like a man in his 60s. Like Rowena, “Old Abe” has declined vermification, and remains content follow Hoag and the Tuttles until he joins his beloved Anna in Paradise. Now 80 years old, Barzillai Coffin is nominally a Bons pêcheur elder, but like Rowena and Absalom, he refuses to extend his life. Having outlived two wives, Old Barzo plans to die peacefully of “natural old age.” Although rumors of his repentance and conversion to Quakerism are unfounded, the oldest surviving Black Macy has indeed resettled in Nantucket, and has little to do with the Covenant’s daily affairs.

Moving from the shadows, the most powerful active member of the Covenant is Judge Return-to-Dust Whicher, a pillar of the Kingsport community at age 66. Next is Absalom’s 54-year old son Isaac Macy, Worshipful Master of the Kingsport Freemasons; followed by Gideon Sleet, his nephew Jacob Macy, and Gideon’s son Addison. Although Fletcher Tuttle is still alive, he constrains himself to offering financial assistance from his comfortable retirement in Boston.

Actively pursuing the Covenant’s goals on the four oceans are, in order of seniority: Ezra Coffin on the island of Kith Kohr, Seth Warnock’s son Nathaniel Warnock on the Aldebaran, Jeremiah Joab and William Pynchon on the Quiddity, Tarrant Hussey on the Celaeno, Ichabod Allen on the Tethys, Samuel Blood’s son Julian Blood on the Persephone, Peleg Baker on the Spindrift, and Lazarus Sleet on the Dragonspark.

Supporting these Quéraudes—Bons pêcheurs who have attained the Fifth Degree or higher—are dozens of lesser cultists scattered throughout Kingsport and Essex County. Generally unaware of the Great Work, they range from promising Freemasons to “useful idiots” cultivated for their advantageous social positions. Two likely to be encountered by the player characters include Reverend Thomas Jane Ruggles at the Congregational Church, and Alan B. Rooke at the Kingsport Library. Technically, Lady Jezebel is a Second Degree initiate, but she’s been considered inactive since her estrangement from Gideon Sleet. (For a complete explanation of Covenant Degrees and powers, see “Kingsport Cult Degrees.”)

Coda: The Covenant and the Cthulhu Mythos

It may seem strange that the Covenant directs its worship to Dagon and not Cthulhu. After all, the R’lyeh Text centers on Cthulhu, as do the Black Book Codices. However, the Bons pêcheurs are not a Cthulhu cult, and have no desire to awaken the Dead Dreamer. Their goal is to achieve paradise on earth—the rest of the cosmos can take care of itself. As the Covenant deepened their understanding of l’Ancienne Religion over the centuries, three schools of thought emerged regarding Cthulhu and the Great Old Ones: the Traditionalists, the Zealots, and the Quaripels.

Of these three coteries, the Traditionalists have the most adherents. Also known as the Gnostics, and sometimes pejoratively as the Templars, Traditionalists like Isaiah and Rowena Tuttle regard the Mythos as an evolution of the Cathar heresies of Estienne Mordant. Not ready to abandon a Judeo-Christian universe, they believe the Great Old Ones are archons, fallen angels, and demons. They acknowledge the undeniable terror and strangeness of these “Others,” but how are they truly different from the Nephilim of Genesis, the monsters of Job, the angels of Ezekiel, or the visions of John the Revelator?

In 1735 Abner Ezekiel Hoag brought the Ponape Scripture to Kingsport. Fascinated with l’Ancienne Religion since his first exposure to the Necronomicon, Hoag saw the Ponape Scripture as a radical break from the Covenant’s hoary tradition of witchcraft and Gnosticism. Unlike the Tuttles, Hoag didn’t require medieval Christianity as a scaffold for this terrible new pantheon. The discovery of the R’lyeh Text only strengthened his belief: the Great Old Ones were alien monstrosities in a godless universe. The best humans could hope for was cosmic indifference. During a heated debate over the Ponape Scripture, Rowena mocked Hoag as a “goddamn zealot.” Hoag nodded in recognition and proudly adopted the label as his own. Hoag and fellow Zealots like Ezra Coffin and William Pynchon take the Mythos literally. While they are dedicated to resurrecting—and controlling—Dagon, they feel it’s best to step quietly around Cthulhu and the “Others.”

In 1817, Judge Return Whicher printed a tract for private distribution among his fellow Quéraudes. Entitled A Modern Theological Response to Bertrane Quaripel and the Guernsey Coven, the pamphlet gave voice to those Bons pêcheurs who rejected the Tuttles’ Gnosticism and Hoag’s fundamentalism. Whicher argued that the more outré elements in l’Ancienne Religion were simply “Ancestor mythology.” Stories of Cthulhu’s extraterrestrial origin and his wars among the Great Old Ones should be read as allegories; an Ancestor Book of Genesis. The ancient authors of the R’lyeh Text merely added their own version of the story to an older myth, like the Bible repeating the Great Flood of Sumerian legend, or the Romans pillaging the Greeks. For this reason, the Guernsey Coven was actually correct when they conflated Cthulhu with Dagon—it’s all the same basic story. Although his argument was more sophisticated than Quaripel’s Dee-influenced witchcraft, Whicher and supporters such as Barzillai Coffin and Fletcher Tuttle were quickly dubbed the “Quaripels.”

While these coteries differ in their philosophical approach to l’Ancienne Religion, they are united in their goal to complete the Great Work. Whether you name him K’th-oan-esh-el, Dagon, or Satan, Rex Mundi must be liberated from his prison if humans are to achieve divinity. There is only One Demiurge, One Resurrection, One Apocalypse, One Great Work, and One Covenant of the Green Flame.

White Leviathan > Keeper’s Information

[Back to History of Dagon | White Leviathan TOC | Forward to The Great Work]

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 9 March 2024

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

White Leviathan PDF: [TBD]