Borges Poetry II – Mid-Career

- At August 07, 2018

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

Poetry is a mysterious chess, whose chessboard and whose pieces change as in a dream and over which I shall be gazing after I am dead.

—Jorge Luis Borges, revised preface to “The Self and the Other,” 1969.

Borges Works: Poetry II

This page presents Borges’ poetry published in the 1960s, a decade marked by several sprawling collections that changed quickly across several revisions. The collections are presented in chronological order.

El hacedor / Dreamtigers (1960)

Para las seis cuerdas (1964)

El otro, el mismo (1969)

Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com, unless it’s the original first edition, which just enlarges the image. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

El hacedor

The Maker/Dreamtigers

El hacedor

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1960

Dreamtigers

By Jorge Luis Borges

Prose translations by Mildred Boyer, poetry translations by Harold Morland. Introduction by Miguel Enguídanos

University of Texas Press, 1964

In the early 1960s, Borges had finally achieved international fame, and his works were being translated and published in French, English, Italian, and German. Unfortunately for his publishers in Argentina, Borges had not written any new books in several years. As Borges recalled to Richard Burgin in a 1967 interview:

I said “I haven’t any book.” And then my editor said to me, “Oh yes you have. If you go through your shelves or drawers you’ll find odds and ends. Maybe a book can be evolved from them.” So I think I remember it was a rainy Sunday in Buenos Aires and I had nothing whatever to do…so I thought I’ll look over my papers. Maybe I’ll find something in my drawers. I found cuttings, old magazines, and then I found that there was the book all ready for me.

That book was El hacedor. Four years later it was translated into English and published as Dreamtigers.

A beautiful collection of poems, meditative prose fragments, and unsettling parables, the pieces of El hacedor reflect their scattered origin, conjured from exile and suffused with the pensive melancholy of a rainy Sunday afternoon. (To borrow Borges’ description of his “Dreamtigers,” they seem “submerged and chaotic.”) A dreamy feeling of dislocation and impending revelation drifts through the pieces, which are marked by surreal twists and ambiguous endings. It is easy to see El hacedor as a mid-career turning point, a farewell to the passions of youth and an acknowledgment of an uncertain future. Its format helped shape the remainder of Borges’ career, an eclectic convergence of genres that would find its most faithful successor in Atlas.

Although Borges referred to El hacedor as a “crazy-quilt patchwork,” he considered the book to be his most intimate work, and his best. It contains numerous celebrated pieces, including “Borges and I,” “The Yellow Rose,” and “On Exactitude in Science.” It also features one of Borges’ most famous poems, “El otro tigre,” or “The Other Tiger.” Described by Borges as a “parable” about “the futility of art,” the poem describes three tigers—the first an aesthetic image, the second a living animal, and the third a more sublime ideal:

Let us look for a third tiger. This one

will be a form in my dream like all the others,

a system, an arrangement of human language

and not the flesh-and-bone tiger

that, out of reach of all mythologies,

paces the earth. I know all this; yet something

drives me to this ancient, perverse adventure,

foolish and vague, yet still I keep on looking

throughout the evening for the other tiger,

the other tiger, the one not in this poem.

Another standout is “Límites,” an eight-line inscription included in the “Museum” section and falsely attributed to a fictional poet from Uruguay. Borges’ first statement of what would become a recurring theme in his later work, “Limits” explores the inexorable reduction of possibilities across the span of one’s lifetime:

There is a line by Verlaine that I will not remember again.

There is a street nearby that is forbidden to my feet.

There is a mirror that has seen me for the last time.

There is a door I have closed until the end of the world.

Among the books in my library (I’m looking at them now)

Are some I will never open.

This summer I will be fifty years old.

Death is using me up, relentlessly.

In the same interview quoted above, Borges tells Burgin that the subject felt so completely novel, it gave him the thrill of discovery—“I’m almost as lucky as if I were the first man to write a poem about the joy of spring, or the sadness of the fall or autumn.” Borges returned to “Límites” a few years later, expanding it into a full poem for El otro, el mismo, and then again under the title “La cifra.” The theme continued to haunt Borges’ life, finding its most desolate expression in “A Dream in Germany,” a narrative from 1984’s Atlas.

The contents of El hacedor are listed below. Every poem and narrative from El hacedor is found in Dreamtigers, but the English book does not contain the Spanish originals, in parallel text or otherwise. The thirty poems found in Viking’s Selected Poems are marked by asterisks, some which were published under different English titles. The prose pieces found in Viking’s Collected Fictions are marked by a plus sign (+), and may also have been given different titles. There are some pieces that have been duplicated, appearing in both volumes. Additionally, some of El hacedor’s parables appear in New Direction’s Labyrinths, which was published two years before Dreamtigers.

Part I

- A Leopoldo Lugones (“To Leopold Lugones”)*+

- El hacedor (“The Maker”)*+

- Dreamtigers*+

- Diálogo sobre un diálogo (“Dialogue on a Dialogue”)+

- Las uñas (“Toenails”)+

- Los espejos velados (“The Draped Mirrors”)+

- Argumentum ornithologicum+

- El cautivo (“The Captive”)+

- El simulacro (“The Sham”)+

- Delia Elena San Marco+

- Diálogo de muertos (“Dead Men’s Dialogue”)+

- La trama (“The Plot”)+

- Un problema (“A Problem”)+

- Una rosa amarilla (“The Yellow Rose”)*+

- El testigo (“The Witness”)+

- Martín Fierro+

- Mutations+ [Added to a later edition of El hacedor]

- Parábola de Cervantes y del Quijote (“Parable of Cervantes and Don Quixote”)*+

- Paradiso, XXXI, 108*+

- Parábola del palacio (“Parable of the Palace”)*+

- Everything and Nothing*+

- Ragnarök*+

- Inferno, I, 32+

- Borges y yo (“Borges and I”)*+

Part II

- Poema de los dones (“Poem about Gifts”)*

- El reloj de arena (“The Hourglass”)*

- Ajedrez (“The Game of Chess”)*

- Los espejos (“Mirrors”)*

- Elvira de Alvear

- Susana Soca

- La luna (“The Moon”)*

- La lluvia (“The Rain”)*

- A la efigie de un capitán de los ejércitos de Cromwell (“On the Effigy of a Captain in Cromwell’s Armies”)

- A un viejo poeta (“To an Old Poet”)

- El otro tigre (“The Other Tiger”)*

- Blind Pew

- Alusión a una sombra de mil ochocientos noventa y tantos (“Referring to a Ghost of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Odd”)

- Alusión a la muerte del coronel Francisco Borges (1835–74) (“Referring to the Death of Colonel Francisco Borges”)

- In memoriam: A.R.

- Los Borges*

- A Luis de Camoens (“To Luis de Camoëns”)

- Mil novecientos veintitantos (“Nineteen Hundred and Twenty-Odd”)

- Oda compuesta en 1960 (“Ode Composed in 1960”)

- Ariosto y los árabes (“Ariosto and the Arabs”)*

- Al iniciar el estudio de la gramática anglosajona (“On Beginning the Study of Anglo-Saxon Grammar”)*

- Lucas, XXIII (“Luke XXII”)*

- Adrogué*

- Arte poética*

- Museo (“Museum”):

- Del rigor en la ciencia (“On Exactitude in Science”)*+

- Cuarteta (“Quatrain”)*

- Límites (“Limits”)*

- El poeta declara su mombradía (“The Poet Declares His Renown”)*

- El enemigo generoso (“The Magnanimous Enemy”)*

- Le regret d’Héraclite (“The Regret of Heraclitus”)*

- In Memoriam J.F.K.+ [Added to the fourth edition of El hacedor, 1964]

- Epílogo (“Epilogue”)*

Note on the American Title

The most accurate translation of El hacedor is “The Maker,” but American editors were worried the term had overt religious connotations in English, and failed to capture the multiple valences of the Spanish title. A parallel of the Anglo-Saxon “Shaper” from Beowulf, El hacedor could certainly mean Creator, but was also meant to evoke Homer, Borges, and the mysterious act of creation itself. Instead, they named the collection after the third piece in the book, “Dreamtigers.” A meditation on the futility of the imagination to represent the real, “Dreamtigers” already possessed an English title, and seemed to embody the spirit of the book quite nicely. The modern Viking editions of Borges correctly refer to El hacedor as “The Maker,” but the title Dreamtigers is more frequently used—especially because Dreamtigers is still in print, and does considerably more justice to El hacedor than Viking, which only translates half the book and splits it across two volumes!

Additional Information

The translation of “El otro tigre” quoted above is by Alastair Reid. The translation of “Límites” is by Kenneth Krabbenhoft, who renders the title as “Boundaries” in Viking’s Selected Poems. The entire text of Dreamtigers is available online at The Floating Library. You can read the 1969 revised edition of El hacedor in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF.

Para las seis cuerdas / Milongas

For the Six Strings / Milongas

Obra poética 1923-1964

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1964

Milongas

By Jorge Luis Borges

Illustrations by Ana María Moncalvo

Buenos Aires: Ediciones Dos Amigos, 1983

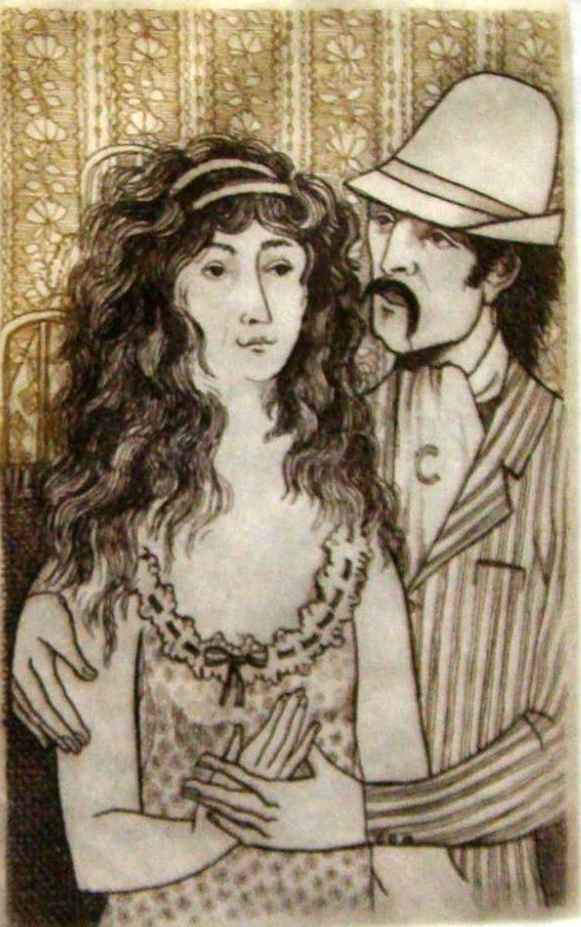

In 1964 Emecé Editores published a fourth edition of Borges’ collected poetry, Obra poética 1923-1964. All the poems that hadn’t been previously collected were compiled under the title “El otro, el mismo,” or “The Self and the Other.” The final section of “El otro, el mismo,” was entitled “Para las seis cuerdas,” or “For the Six Strings,” and consisted of milongas and poems related to music. A year later, Emecé published Para las seis cuerdas as a stand-alone volume with illustrations by Héctor Basaldúa.

The original 1965 edition of Para las seis cuerdas features the nine poems listed below, with the poems included in Selected Poems, 1923-1967 marked by plus-signs (+) and those found in Viking’s Selected Poems marked by asterisks (*). English titles defer to the 1999 Selected Poems.

- Buenos Aires

- Milonga de dos hermanos (“Milonga of the Two Brothers”)+

- ¿Dónde se habrán ido? (“Where Could They Have Gone?”)*

- Milonga para Jacinto Chiclana

- Milonga de Nicanor Paredes (“Milonga of Don Nicanor Paredes”)*

- Un cuchillero en el norte (“A Blade In the Northside”)*

- El títere

- Alguien le dice al tango

- Milonga de los morenos

- Milonga para los orientales

- Los compadritos muertos

Many of the poems in Para las seis cuerdas are written as “milongas,” a type of Argentine folk song that evolved into the tango; or as Borges calls it, “the street ballads of the barrios.” Their themes are familiar to readers of Borges’ earlier work, and include gauchos, war heroes, brothels, vengeance, tango, and of course, murder. Needless to say, most of the milongas do not end well for their titular characters, and it’s a rare poem not pierced by a dagger or bullet!

Many of these pieces were written for a collaborative project with Argentine composer Astor Piazzolla, who set Borges’ lyrics to music on the 1965 recording El tango. As described by Piazzolla scholar John Turci-Escobar:

Piazzolla set all but three of the poems that Borges included in this collection. It seems unlikely that Borges presented “Los compadritos muertos” to Piazzolla since it features hendecasyllable verses, not the characteristic octosyllable versification of these tangos and milongas. Considerations of content, not form, may have excluded “¿Dónde se habrán ido?”: its use of the ubi sunt convention overlaps with that in the poem “El tango”, which appears on the first track of the album. The existence of a prior setting of “Milonga de dos hermanos” by Guastavino may explain why Piazzolla avoided recording or publishing it. Conversely, the fact that Piazzolla avoided recording or publishing “Milonga para los orientales” may explain why it was eventually set by José Basso. To my knowledge, these are the only concordances of Borges milonga texts.

In 1969, Borges revised Para las seis cuerdas for Obras completas, moving “Buenos Aires” and “Los compadritos muertos” back to “El otro, el mismo,” striking “Alguien le dice al tango,” and adding three more milongas: “Milonga de Albornoz,” “Milonga de Manuel Flores,” and “Milonga de Calandria.” In 1970 this arrangement was published as a second edition of Para las seis cuerdas, restoring “Los compadritos muertos” as the final poem. (“Milonga de Albornoz” may be found in both English compilations.)

Milongas

In 1983, Ediciones Dos Amigos in Buenos Aires published Milongas, a book of Borges’ milongas featuring illustrations by Ana María Moncalvo. Milongas features all the relevant poems from Para las seis cuerdas, plus a new piece entitled “Milonga del infiel,” originally written for the tango composer Sebastián Piana.

Additional Information

Ana Cara-Walker explores Borges’ Para las seis cuerdas in her 1983 paper, “Borges’ Milongas: The Chords of Argentine Verbal Art.” John Turci-Escobar discusses Borges and Piazzolla in his 2011 paper, “Rescatando al Tango para una Nueva Música: Reconsidering the 1965 Collaboration Between Borges and Piazzolla.” You may view some of Moncalvo’s artwork in the Milongas at the J. Willard Marriott Library in Utah. You can read the 1969 revised edition of Para las seis cuerdas in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF. You can read the 1972 English translations in Selected Poems, 1923-1967, available as a 375-page PDF.

El otro, el mismo

The Self and the Other

El otro, el mismo

By Jorge Luis Borges

Illustrations by Raúl Soldi

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1969

Online at: Internet Archive

In 1964 Emecé Editores published a fourth edition of Borges’ collected poetry, Obra poética 1923-1964. All the poems that hadn’t been previously collected were compiled under the heading “El otro, el mismo,” or “The Self and the Other.” Borges made a few more revisions for the second edition, Obra poética 1923-1966. In 1969 Emecé produced Obras completas, or “Complete Works,” and Borges made his most extensive revisions, adding new prefaces to each collection and consigning unliked poems to oblivion. Emecé used the opportunity to finally publish El otro, el mismo as a stand-alone volume with illustrations by painter Raúl Soldi. Curiously, they included all the poems from El hacedor and Para las seis cuerdas, bringing the book’s page count to 263!

The 1969 edition of El otro, el mismo features the 118 poems listed below, which includes every poem from El hacedor, and poems that appeared in Para las seis cuerdas, published in 1965. Poems marked by an asterisk (*) are found in Viking’s Selected Poems, which include fifty poems from El otro, el mismo, thirteen from El hacedor, and five from Para las seis cuerdas. Poems included in Selected Poems, 1923-1967 are marked by a plus-sign (+), which also includes “Lines I Might Have Written and Lost Around 1922” and “The Labyrinth.” English titles defer to the 1999 Selected Poems.

- Prólogo (“Prologue”)*

- A Leopoldo Lugones (“For Leopoldo Lugones”)*

- Insomnio

- Two English Poems

- La noche cíclica (“The Cyclical Night”)+*

- Del infierno y del cielo (“Of Heaven and Hell”)*

- Poema conjectural (“Conjectural Poem”)+*

- Poema del cuarto elemento (“Poem of the Fourth Element”)*

- A un poeta menor de la antología (“To a Minor Poet of Greek Mythology”)+*

- Página para recordar al Coronel Suárez, vencedor en Junín (“A Page to Commemorate Colonel Suárez, Victor at Junín”)+*

- Mateo, XXV, 30 (“Matthew XXV: 30”)+*

- Una brújula (“Compass”)+*

- Una llave en Salónica

- Un poeta del siglo XIII (“A Poet of the Thirteenth Century”)+*

- Un soldado de Urbina (“A Soldier of Urbina”)+*

- Límites [De estas calle…] (“Limits”)+*

- Baltasar Gracián*

- Un sajón (449 A.D.) (“A Saxon”)+*

- El Golem (“The Golem”)+*

- El tango

- Poema de los dones (“Poem about Gifts”)+*

- El reloj de arena (“The Hourglass”)*

- Ajedrez (“The Game of Chess”)+*

- Los espejos (“Mirrors”)*

- Elvira de Alvear+

- Susana Soca+

- La luna (“The Moon”)*

- La lluvia (“The Rain”)+*

- A la efigie de un capitán de los ejércitos de Cromwell (“On the Effigy of a Captain in Cromwell’s Armies”)

- A un viejo poeta (“To an Old Poet”)

- El otro tigre (“The Other Tiger”)+*

- Blind Pew

- Alusión a una sombra de mil ochocientos noventa y tantos (“Referring to a Ghost of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Odd”)+

- Alusión a la muerte del coronel Francisco Borges (1835–74) (“Referring to the Death of Colonel Francisco Borges”)+

- In memoriam: A.R.

- Los Borges+*

- A Luis de Camoens (“To Luis de Camoëns”)

- Mil novecientos veintitantos (“Nineteen Hundred and Twenty-Odd”)

- Oda compuesta en 1960 (“Ode Composed in 1960”)

- Ariosto y los árabes (“Ariosto and the Arabs”)*

- Al iniciar el estudio de la gramática anglosajona (“On Beginning the Study of Anglo-Saxon Grammar”)+*

- Lucas, XXIII (“Luke XXII”)+*

- Adrogué*

- Arte poética+*

- El otro

- Una rosa y Milton (“A Rose and Milton”)+*

- Lectores (“Readers”)+*

- Juan, I, 14 (“John I: 14”)*

- El despertar (“Waking Up”)*

- Buenos Aires

- A quien ya no es joven (“To One No Longer Young”)+*

- Alexander Selkirk*

- Odisea, libro vigésimo tercero (“Odyssey, Book Twenty-Three”)+*

- El

- Sarmiento

- A un poeta menor de 1899 (“To a Minor Poet of 1899”)+*

- Texas+*

- Composición escrita en un ejemplar de la gesta de Beowulf (“Poem Written in a Copy of Beowulf”)+*

- Hengist Cyning+

- Fragmento (“Fragment”)+

- A una espada en Yorkminster (“To a Sword at York Minster”)*

- A un poeta sajón (“To a Saxon Poet”)+

- Snorri Storluson (1179-1241)+

- A Carlos XII (“To Charles XII of Sweden”)+

- Emanuel Swedenborg+*

- Jonathan Edwards (1703-1785)+*

- Emerson+*

- Edgar Allan Poe+

- Camden, 1892+*

- París 1856+

- Rafael Cansinos-Asséns+

- Los enigmas (“The Enigmas”)+*

- El instante (“The Instant”)*

- Al vino

- Soneto al vino

- 1964*

- El hambre

- El forastero (“The Stranger”)*

- A quién está leyéndome (“To Whoever Is Reading Me”)*

- El alquimista (“The Alchemist”)*

- Alguien (“Someone”)+*

- Everness+*

- Ewigkeit+

- Edipo y el enigma (“Oedipus and the Enigma”)+*

- Spinoza+*

- España

- Elegía (“Elegy”)*

- Adam Cast Forth+*

- A una moneda (“To a Coin”)+*

- Otro poema de los dones (“Another Poem of Gifts”)+

- Oda escrita en 1966 (“Ode Written in 1966”)+*

- El sueño (“Dream”)*

- Junín+

- Un soldado de Lee (1862) (“A Soldier Under Lee”)+

- El mar (“The Sea”)+*

- Una mañana de 1649 (“A Morning of 1649”)+*

- Buenos Aires

- A un poeta sajón (“To a Saxon Poet”)*

- Al hijo (“To the Son”)*

- El Puñal (“The Dagger”)+*

- Los compadritos muertos

- Para las seis cuerdas:

- Milonga de dos hermanos (“Milonga of the Two Brothers”)+

- ¿Dónde se hábran ido? (“Where Can They Have Gone?”)*

- Milonga de Jacinto Chiclana

- Milonga de don Nicanor Paredes*

- Un cuchillero en el norte (“A Blade in the Northside”)*

- El títere

- Milonga de los morenos

- Milonga de los orientales

- Milonga de Albornoz.+*

- Museo:

- Cuarteta (“Quatrain”)*

- Límites (“Limits”)*

- El poeta declara su mombradía (“The Poet Declares His Renown”)*

- El enemigo generoso (“The Magnanimous Enemy”)*

- Le regret d’Héraclite (“The Regret of Heraclitus”)*

Because they were written as individual pieces, the poems of El otro, el mismo lack the cohesive unity of Borges’ earlier collections, and many are variations on related themes, described by Borges himself as “Buenos Aires, the cult of my ancestors, the study of the German language, [and] the contradiction between the passing of time and the ego which endures.” Nevertheless, in his 1969 preface Borges describes El otro, el mismo as his favorite collection, and it features two poems he discussed extensively in contemporary interviews.

The first, “El Golem,” is one of Borges’ longer poems. A retelling of the Jewish fable, Borges uses the legendary monster to explore the relationship between creator and creation, whether the rabbi and his golem, God and the rabbi, or the poet and his poem:

So, composed of consonant and vowels,

there must exist one awe-inspiring word

that God inheres in—that, when spoken, holds

Almightiness in syllables unslurred.

[…]

Thirst to know things only known to God,

Judah León shuffled the letters endlessly,

trying them out in subtle combinations

Till at last he uttered the Name that is the Key.

[…]

In his hour of anguish and uncertain light,

upon his Golem his eyes would come to rest.

Who is to say what God must have been feeling,

Looking down and seeing His rabbi so distressed?

The second of Borges’ personal favorites is “Límites.” Bearing the same title as the eight-line “inscription” from El hacedor, the new “Limits” continues the original’s theme, presenting the slow march of time as a progressive delimiting of a man’s possible experiences. Although the poem has been frequently translated, it lacks the immediacy and power of its shorter precursor. Where the original ended starkly with “This summer I will be fifty years old. / Death is using me up, relentlessly,” the expanded version concludes on a more philosophical note:

At dawn I seem to hear the turbulent

murmur of the crowds milling and fading away;

they are all I have been loved by, forgotten by;

space, time, and Borges are now leaving me.

Another fascinating aspect of El otro, el mismo is its extended prologue. While Borges’ new prefaces for Fervor de Buenos Aires, Luna de enfrente, and Cuaderno San Martín were animated by the need to explain away his youthful indiscretions, the poems of El otro, el mismo received a more balanced treatment. Written shortly after he finished the Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard, the preface of El otro, el mismo opens a discussion of poetry that rolls across his next few prologues, a wandering and congenial conversation that takes a decade to unwind. Borges concludes his preface with lines as beautiful and mysterious as any poem to follow:

The roots of language are irrational and of a magical nature. The Dane who pronounced the name of Thor or the Saxon who uttered the name of Thunor did not know whether these words represented the god of thunder or the rumble that is heard after the lightning flash. Poetry wants to return to that ancient magic. Without fixed rules, it makes its way in a hesitant, daring way, as if moving in darkness. Poetry is a mysterious chess, whose chessboard and whose pieces change as in a dream and over which I shall be gazing after I am dead.

Additional Information

The translation of “El Golem” quoted above is by Alan S. Trueblood. The translation of “Límites” is by Alastair Reid. The excerpt from the prologue was translated by Alexander Coleman. Many of the poems from the 1964 El otro, el mismo are online at Literatura. You can read the 1969 revised edition of El otro, el mismo in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF. You can read the 1972 English translations in Selected Poems, 1923-1967, available as a 375-page PDF.

Borges Works

Main Page — Return to the Borges Works main page and index.

Fictions and Artifices — Short stories; the core Borges works.

Nonfiction — Collections of essays and criticism.

Collaborations with Bioy Casares — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Collaborations with Others — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with others.

Poetry Compilations — Selections of Borges’ verse translated into English and published as compilations.

Poetry I — Early post-ultraísmo poetry, 1923 to 1943.

Poetry III — Late poetry books from 1969 to 1985.

Lectures, Conversations, and Interviews — Collections of Borges’ lectures, conversations, and interviews.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 12 August 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com