Borges Fiction

- At July 22, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

1

1

A book is more than a verbal structure or series of verbal structures; it is the dialogue it establishes with its reader and the intonation it imposes upon his voice and the changing and durable images it leaves in his memory. A book is not an isolated being: it is a relationship, an axis of innumerable relationships.

—Borges Luis Borges, “A Note on (toward) Bernard Shaw”

Borges Works: Fictions & Artifices

The works featured on this page are:

Collected Fictions

Historia universal de la infamia / A Universal History of Infamy

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan

Ficciones

El Aleph / The Aleph and Other Stories

El hacedor / Dreamtigers

Antología Personal / Personal Anthology

Labyrinths

El informe de Brodie / Doctor Brodie’s Report

El libro de arena / The Book of Sand

The Library of Babel (Illustrated)

Everything and Nothing

The books are presented in chronological order; with the exception of Collected Fictions, which takes pride of place at the beginning. All book images include the Spanish first edition where appropriate; subsequent English translations are generally represented by their most “current” covers. Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com, unless it’s the original first edition, which just enlarges the image. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

Collected Fictions

Collected Fictions By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Viking, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

Collected Fictions By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Penguin, 1999 |

In 1999 the literary world celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of Borges’ birth. This “Borges Centennial” was marked by numerous lectures, conferences, and artistic projects, from performances of Borges-themed tango to exhibitions of original manuscripts. One of the most anticipated events was Penguin-Viking’s publication of three massive volumes of Borges’ work, each dedicated to a different genre: his short stories, his non-fiction, and his poetry. It was the first time a single publisher had attempted to collect, curate, and translate the bulk of Borges’ impressive oeuvre, and it was justly celebrated as a watershed of Borges translation.

The first of these volumes was Collected Fictions, released in 1998. Not only could a reader finally hold Borges’ collected fiction in a single volume, many of the stories had been long out of print, or available only in the original Spanish. As such, Collected Fictions is a treasure trove of Borges rarities, from the “universal iniquities” of his youth to his final story, “Shakespeare’s Memory.”

Collected Fictions represents the heroic efforts of a single translator, Andrew Hurley, who brings a marvelous consistency to a diverse body of work spanning half a century. Hurley taps into Borges’ crisp yet sonorous Spanish, giving the stories a natural rhythm and fluidity, and every detail is rendered with a lucid transparency. One senses a kind of rightness, or accuracy, in both word choices and popular idiom. Additionally, Hurley recognizes the wonderful humor in Borges, and many of these stories contain a welcome twinkle of irony. This being said, there are occasions where one misses the poetic liberties taken by earlier translators. For instance, “Funes the Memorious” is now drably rendered as “Funes, His Memory,” and A Universal History of Infamy has been changed to the less stirring and more fussy A Universal History of Iniquity. While some of these older translations may take liberties with Borges’ Spanish, Hurley’s corrections bring to mind Borges’ comment, “The original is not faithful to the translation.” (Twenty years after their publication, Hurley wrote an essay on his challenges translating these works for Inverse Journal.)

Collected Fictions includes the stories found in these previous collections: A Universal History of Infamy (1935), Ficciones (1944), The Aleph (1949), Doctor Brodie’s Report (1970), and The Book of Sand (1975). It extracts the prose pieces from El hacedor (1960) (a.k.a. Dreamtigers) and In Praise of Darkness (1969), but leaves the poetry in these collections for Selected Poems. It also features the four previously-untranslated stories from the “Shakespeare’s Memory” section of Obras Completas 1975-1985. Unfortunately, Collected Fictions does not contain the stories Borges co-wrote with Adolfo Bioy-Casares under the joint pseudonym “Bustos Domecq”; nor does it contain The Book of Imaginary Beings. The anthology closes with an appendix of useful notes. Here Hurley annotates some of the more exotic locations and obscure personalities featured in the stories, and points out nuances that might be missed by a reader unfamiliar with Spanish or its Argentine dialects.

While experienced readers may miss the familiar translations of Anthony Kerrigan, Anthony Alastair Reid, and Norman Thomas di Giovanni; and the omission of the “Bustos Domecq” stories is regrettable, these criticisms should not detract from praising this extraordinary and significant work. If you plan on owning a single volume of Borges’ stories, Collected Fictions is the obvious first choice.

Historia universal de la infamia

A Universal History of Infamy

Historia universal de la infamia By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Editorial Tor, 1935 |

Historia universal de la infamia [1954 Revision] By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1954 Online at: Internet Archive |

A Universal History of Infamy By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni New York: E.P. Dutton, 1972 Online at: Internet Archive |

A Universal History of Infamy By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni London: Allen Lane, 1973 Online at: Teacher’s Crate |

A Universal History of Iniquity

A Universal History of Iniquity (Included in Collected Fictions) By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Viking, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

A Universal History of Iniquity By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Penguin Classics, 2004 |

From August 1933 to January 1934, Borges published a series of biographical sketches in the Buenos Aires newspaper Crítica. “Falsifications and distortions” of stories Borges read elsewhere, each sketch outlines the career of a notorious scoundrel; a lurid account of violence, malfeasance, and betrayal. Borges adopts a sardonic tone throughout the pieces, illuminating his rogues gallery with flashes of paradox and wit and often concluding with an ironic twist. Hovering between biography and fiction, the sketches represent some of Borges’ earliest forays into literary invention. (He would later identify Robert Louis Stevenson, G.K. Chesterton, and the gangster films of Josef von Sternberg as inspirations.)

First Edition

In 1935 Editorial Tor collected these sketches as Historia universal de la infamia, including an additional piece written just for the book—“The Disinterested Killer Bill Harrigan.” To flesh out the book, thesketchess sketches were followed by “Hombre de la esquina rosada,” a short story about a knife-wielding compadrito originally presented under the cautious pseudonym “Francisco Bustos.” Although Borges would later disparage “Man on Pink Corner” as a “laboured composition,” it was his first mature attempt at original fiction, and has been much anthologized over the years. (It also enhanced Borges’ misplaced notoriety as a poet of the barrios!) Historia concludes with “Etcétera,” a section of parodistic fragments which Borges brazenly attributed to authors such as Burton and Swedenborg.

Revision

Borges revised Historia in 1954, adding three additional pieces to the “Etcétera” section: “Mahomed’s Double,” “The Generous Enemy,” and “On Exactitude in Science.” This revision includes a second preface, which begins: “I should define as baroque that style which deliberately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its possibilities and which borders on its own parody.” In an attempt to place distance between himself and his infamous infamies, he dismisses his sketches as the “irresponsible games” of a “shy young man.”

Like many of Borges’ remarks about his own writing, this genial self-effacement misdirects a reader from what is, in truth, an acute self-awareness of his development as an artist. In the twenty years between editions, Borges had published two masterpieces, Ficciones and El Aleph, and French translations of his work were establishing his reputation in Europe. In a very real way, when Borges returned to Historia he closed the arc of a circle—after the 1950s, Borges would shift his creative focus from fiction to poetry, the literary passion that animated his youth. Although a few prose pieces in El Hacedor (1960) and The Book of Sand (1970) bear typical “Borgesian” elements, he would never completely return to the style of Ficciones. In fact, with the help of collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares, Borges went on to whimsically parody his own work—the pieces found in The Chronicles of Bustos Domecq (1969) are the true “deliberate exhaustions,” deconstructing the Borgesian style by extending its aesthetic conceits into the realm of absurdity.

Far from overworked self-parodies, the Historia sketches shimmer with audacity and youthful invention. Here is a creator just coming into his powers, planting the seeds that would soon blossom into a garden of forking paths—there is a direct line from Historia to Ficciones. Despite the modesty of his second preface, Borges surely realized this. After all, in declining to revise the pieces, he archly invoked none other than the Apostle John: “What I have written I have written.” It’s not too difficult to detect a flash of pride behind his ironic bombast. Indeed, several Latin America writers have cited Historia as being particularly inspirational—the surreal sense of authenticity, the fusion of fact and fiction presented with deadpan objectivity, the unabashed fondness for paradox; all of these “Borgesian” elements are hallmarks of the Latin American Boom and so-called “magical realism.”

The Norman Thomas di Giovanni Translation

The first English translation of Historia universal de la infamia was published by E. P. Dutton of New York, who commissioned Norman Thomas di Giovanni to work closely with Borges to ensure faithful renditions. (Details of this project may be found below, under The Aleph and Other Stories, the first such volume released by Dutton.) The 1972 edition gives the following contents, largely identical to the 1954 Spanish revision:

- The Dread Redeemer Lazarus Morell

- Tom Castro, the Implausible Imposter

- The Widow Ching, Lady Pirate

- Monk Eastman, Purveyor of Iniquities

- The Disinterested Killer Bill Harrigan

- The Insulting Master of Etiquette Kôtsuké no Suké

- The Masked Dyer, Hakim of Merv

- Streetcorner Man (di Giovanni’s title for “Hombre de la esquina rosada”)

- Et cetera, including: “A Theologian in Death,” “The Chamber of Statues,” “Tale of the Two Dreamers,” “The Wizard Postponed,” “The Mirror of Ink,” “A Double for Mohammed,” “The Generous Enemy,” and “On Exactitude in Science.”

- Index of Sources

The Dutton translation was acquired in the UK by Allen Lane, and a UK hardcover came out in 1973. In 1975 it was copyrighted by Penguin, who released Historia in paperback as part of the “Penguin Modern Classics” series. Dutton’s US paperback came out in 1979, its lurid James McMullan cover doing little to dispel the notion that Borges was a chronicler of the Buenos Aires underworld!

The Andrew Hurley Translation

Andrew Hurley produced a new translation of Historia for Viking’s Collected Fictions in 1998. Restoring Borges’ “pink” back to di Giovanni’s “Streetcorner Man,” Hurley boldly—and perhaps unwisely—retitled the collection A Universal History of Iniquity. In 2004, Penguin published History as a separate paperback with the following contents:

- The Cruel Redeemer Lazarus Morell

- The Improbable Imposter Tom Castro

- The Widow Ching – Pirate

- Monk Eastman, Purveyor of Iniquities

- The Disinterested Killer Bill Harrigan

- The Uncivil Teacher of Court Etiquette Kôtsuké no Suké

- Hakim, the Masked Dyer of Merv

- Man on Pink Corner

- Et cetera, including: “A Theologian in Death,” “The Chamber of Statues,” “The Story of the Two Dreamers,” “The Wizard that Was Made to Wait,” “The Mirror of Ink,” “Mahomed’s Double,” “The Generous Enemy,” and “On Exactitude in Science.”

- Index of Sources

As a final note, I should mention a curious reversal that would have made Borges smile in amusement. In a case of student surpassing the teacher, Thunder’s Mouth Press uses an excerpt from “Monk Eastman, Purveyor of Iniquities” as the foreword to their edition of Herbert Asbury’s Gangs of New York, the very book that inspired Borges’ Eastman sketch in the first place!

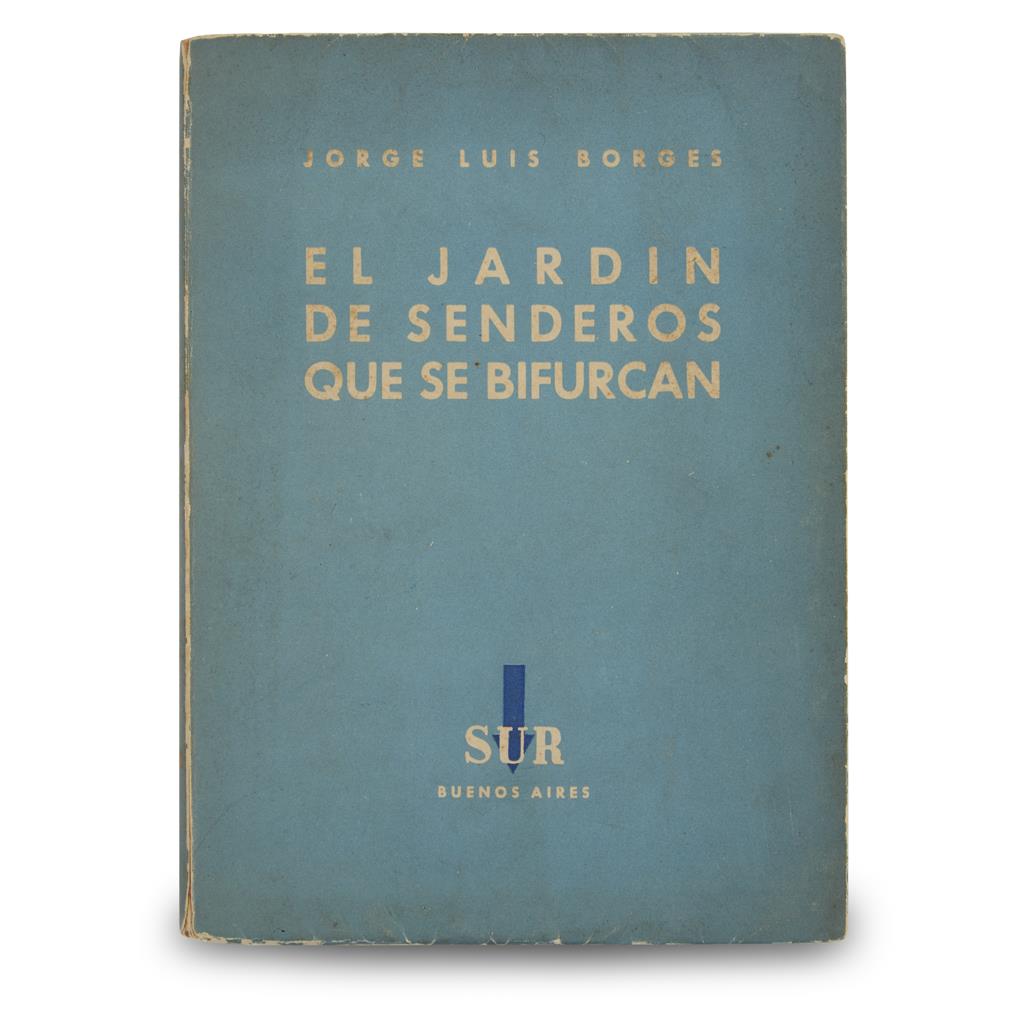

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Sur, 1941

Translated as “The Garden of Forking Paths,” this collection of stories represents Borges’ attempt to re-establish himself as a writer after a near-fatal illness. Because El jardín forms part of the better-known Ficciones, it is described in detail below.

Ficciones

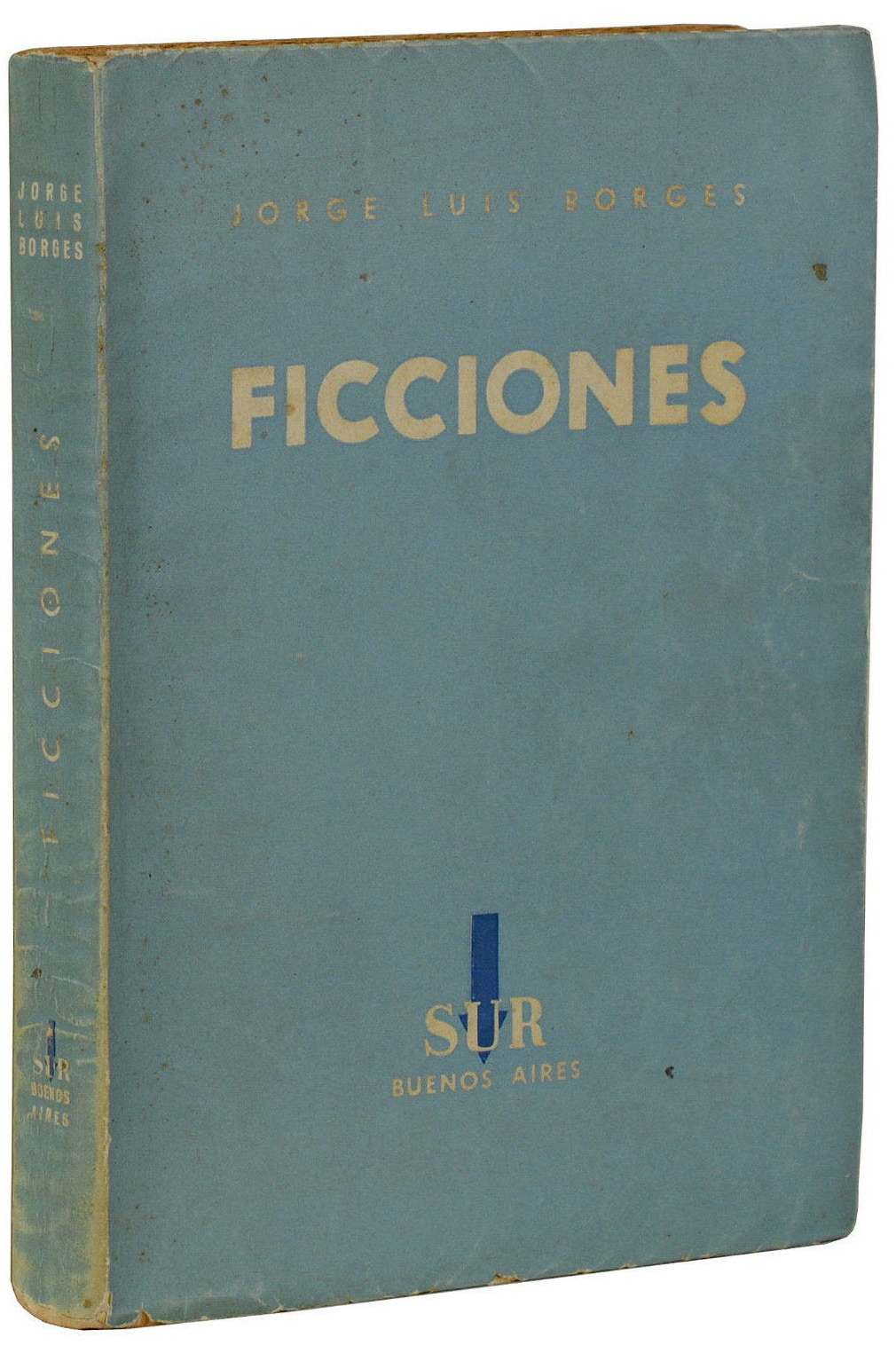

Ficciones By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Sur, 1944 |

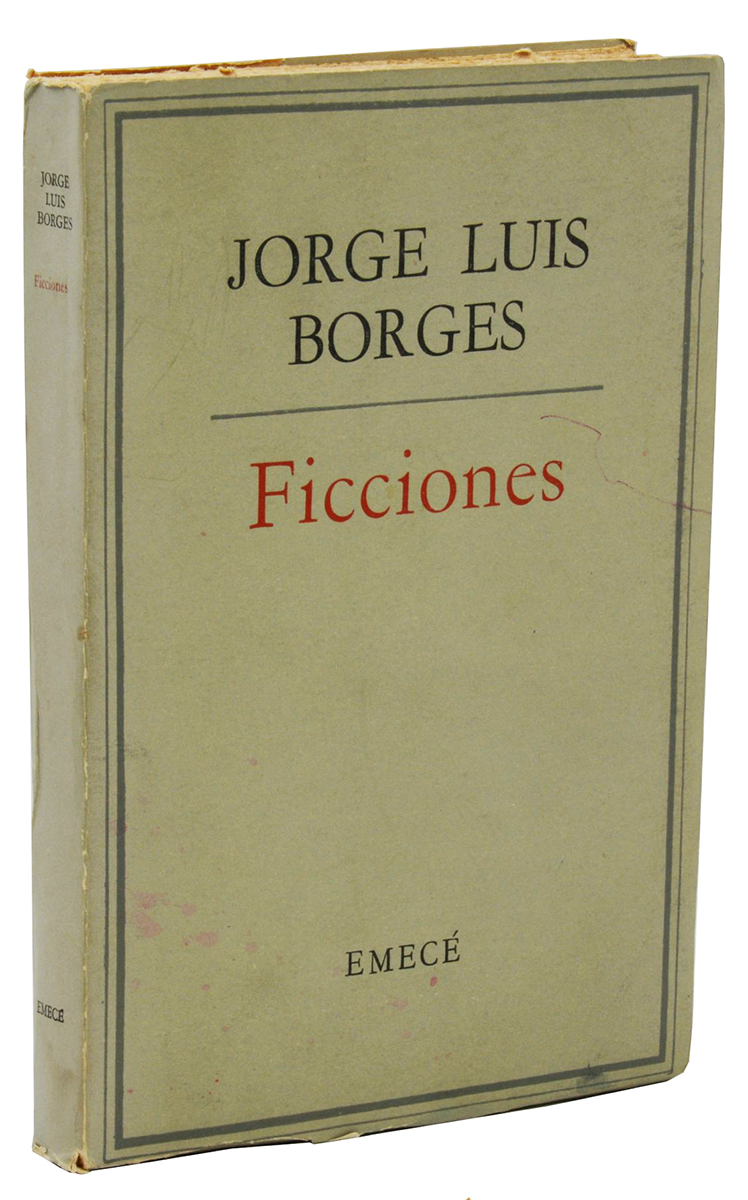

Ficciones By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1956 Online at: Internet Archive |

Ficciones |

Ficciones |

Ficciones |

Ficciones

(Included in Collected Fictions)

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Andrew Hurley

Viking, 1998

Online at: Internet Archive

In 1941, Borges published El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan, or “The Garden of Forking Paths,” a collection of seven new stories plus an earlier story called “The Approach to al-Mu’tasim.” This was followed by nine additional stories under the title Artifices. In 1944, El jardín and Artifices were bundled together and published as Ficciones. (Although the title means “Fictions,” the original Spanish title is always retained for English translations.) A cornerstone of postmodern literature, Ficciones is Borges’ most enduring and influential work.

Ficciones is divided into two sections: “The Garden of Forking Paths,” which contains the contents of the original El jardín collection, and the later “Artifices.” Although the stories of the “Garden” section are generally longer and somewhat more fantastical than those in “Artifices,” all the stories in Ficciones explore the labyrinthine nature of reality and the impact of language on literature, philosophy, metaphysics, and theology. Many stories describe or even review imaginary books penned by fictional authors, and more than a few engage in flights of meta-reality where reality and fiction are seamlessly intertwined. The contents are given below, presented with the original Grove Press titles:

The Garden of Forking Paths

- “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” A reference to an imaginary country leads the author deeper into a different linguistic and metaphysical reality.

- “The Approach to Al-Mu’tasim.” A review of a mystery novel concerned with the quest for an unreal person.

- “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.” Borges explains why Menard’s twentieth century version of Don Quixoteis superior to that of Cervantes, despite being identical.

- “The Circular Ruins.” A mystic visionary attempts to dream a human into being.

- “The Babylon Lottery.” The Kafkaesque history of a society ruled by the random, invisible, and godlike Company.

- “An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain.” Reviews of three strange pieces of fiction by a very unusual author.

- “The Library of Babel.” The tale of a man, perhaps Borges himself, a caretaker in an infinite library.

- “The Garden of Forking Paths.” A mystery about an impossible book and a mythical labyrinth.

Artifices

- “Funes, the Memorius.” A nineteen year old invalid reveals that language is an inadequate tool for those who can forget nothing.

- “The Form of the Sword.” The tale of an Irish expatriate and the scar on his face.

- “Theme of the Traitor and Hero.” When history repeats literature, looking deeper reveals the hand of hidden forces.

- “Death and the Compass.” A detective story in which the ineffable name of God is the principal clue.

- “The Secret Miracle.” A writer’s final days under a Nazi death sentence.

- “Three Versions of Judas.” A review of the work of Nils Runeberg, a modern heresiarch, and his views on the nature of Judas Iscariot.

- “The End.” A completion of José Hernández’ great folk poem about Martín Fierro.

- “The Sect of the Phoenix.” The sectarians are a cult that have survived the ages, judiciously keeping the secret which unites them.

- “The South.” In this semi-autobiographical tale, a copy of the Thousand and One Nights precipitates the strange sickness of an Argentine nationalist.

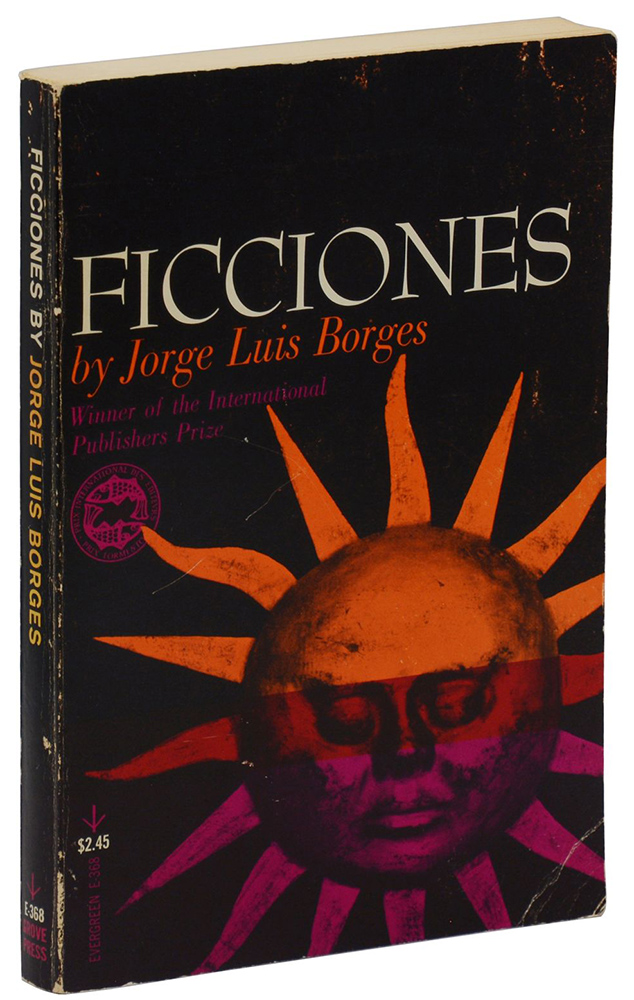

While Ficciones brought Borges some recognition in the Spanish-speaking world, it wasn’t until the collection was translated into French in 1951 that his name traveled deeper into Europe. In 1961 Borges won the first-ever Formentor Prix International, a new award dedicated to honoring those authors whose work will “have a lasting influence on the development of modern literature.” Conceived and awarded by a panel of five international publishers—including New York’s Grove Press—the first prize of $10,000 was divided between Borges and the Irish expatriate Samuel Beckett. Although neither Borges nor the Prix Formentor were well known to the world at large, one of the benefits of the award was the translation and publication of the recipient’s work in each country represented by the panel: Spain, Italy, England, the United States, and Germany. Grove Press published an English translation of Ficciones in 1962, and Borges was soon catapulted into the international spotlight.

Notes on Ficciones

A masterpiece of modern literature, I recommend Ficciones to anyone and everyone. I believe these stories comprise some of the most powerful thoughts about reality put to paper under the guise of fiction. While it would be both inaccurate and an exaggeration to suggest that Borges “invented” postmodernism with these works, their impact upon modern literature is incalculable. European OuLiPo, American postmodernism, the Latin American “Boom,” avant-garde science fiction, literary fantasy, modern weird fiction, literary and cultural criticism, even comic books—an exhaustive catalog of writing influenced by Borges would not only fill this site, it would overflow into countless other anthologies, magazines, and libraries.

So which version of Ficciones should you purchase? Because Viking’s Collected Fictions contains Ficciones and much more, it seems like an obvious choice. However, as much as I respect Andrew Hurley’s translations, the original team assembled by Grove Press produced the “classic” edition of Ficciones—a more poetic King James version compared to a more accurate New Revised Standard, if you will! (This team included Anthony Kerrigan, Anthony Bonner, Alastair Reid, Helen Temple, and Ruthven Todd.) Therefore I recommend purchasing Ficciones separately, preferably in addition to Collection Fictions. Although the Grove Press paperback is less expensive, the hardcover edition from Knopf’s “Everyman’s Library” series deserves special note, and its introduction, short biography, and chronology are worth the extra price.

El Aleph

The Aleph and Other Stories

El Aleph By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada, 1949 |

El Aleph By Jorge Luis Borges Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1957 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Aleph and Other Stories 1933-1969

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

New York: E. P. Dutton, 1970

Online at Internet Archive

The Aleph and Other Stories (Included in Collected Fictions) By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Viking, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Aleph and Other Stories By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Penguin Classics, 2004 |

Originally published in 1949, El Aleph was the second major collection of Borges’ short stories, many of which had appeared in various Argentine literary magazines. In many ways a sequel to Ficciones, the stories of El Aleph find Borges obsessed with the same philosophical themes: the relationship between consciousness and reality, the mystical significance of language and symbols, the mysteries of time and eternity, and the limits of obsession itself. Other familiar elements include copious labyrinths, reviews of fictional books, a casual mixing of reality and invention, and a return to Argentine’s colorful history of gauchos. While the stories are still remarkable, El Aleph lacks the striking originality and urgency of Ficciones—with the notable exceptions of “The Immortal,” “The Zahir,” and “The Aleph,” one of Borges’ most famous creations. Still, it remains an essential and important collection.

Although it took a few editions to stabilize, the seventeen stories in the “final” El Aleph are below, presented with di Giovanni’s titles:

- “The Immortal.” A man’s quest for the City of the Immortals brings him face to face with the Absolute.

- “The Dead Man.” A story of revenge and betrayal among knife-wielding gauchos.

- “The Theologians.” An exploration of the line between heresy and orthodoxy.

- “Story of the Warrior and the Captive.” A barbarian who becomes enlightened and a civilized woman who prefers the savage are found to be more similar than not.

- “A Biography of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz (1829-1874).” A gloss on the gauchesco poem Martín Fierro.

- “Emma Zunz.” A tale of justice and displacement.

- “The House of Asterion.” The inhabitant of an infinite house tells a familiar story.

- “The Other Death.” The subtle effects upon reality when God grants two deaths to the same man.

- “Deutsches Requiem.” A convicted and condemned Nazi chillingly justifies his atrocious actions.

- “Averroës’ Search.” Without a frame of reference, can there be a clear picture of the unknown?

- “The Zahir.” A random memory becomes a destructive spiritual predator.

- “The God’s Script.” In a Spanish prison, an Aztec priest struggles to understand the nature of godhood.

- “Ibn-Hakam al-Bokhari, Murdered In His Labyrinth.” A “closed-room” murder mystery set in the heart of a domestic maze.

- “The Two Kings and the Two Labyrinths.” A lost page from the Thousand and One Nights.

- “The Waiting.” An obsessed ex-criminal prepares to meet his enemy.

- “The Man on the Threshold.” A review of a mystery novel concerned with the quest for an unreal person.

- “The Aleph.” A man trying to recreate the world through poetry shows his friend the Universe below a staircase.

Notes on the English Translations of El Aleph

El Aleph has traveled a long and winding road. In the late 1960s, New York’s E.P. Dutton published a survey of Borges’ fiction, much of it still unavailable in English. The series was edited and translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni, who worked closely with Borges in Buenos Aires to produce translations “in collaboration with the author.” Working in various sessions from 1967–1972, their goal was to make Borges’ stories “read as though they had been written in English.” Closely connected to Allen Lane and Penguin in the UK, all of Dutton’s editions were published in England shortly after their United States premieres. Eventually Penguin acquired Dutton; but sadly the United States editions were allowed to slip out of print. (This was amended in the late 1990s, when new translations by Andrew Hurley were commissioned by Viking, the imprint of Penguin responsible for first publishing Gravity’s Rainbow.)

Although the Grove translation of Ficciones had been in print since 1962, its successor was still largely unknown to the English-speaking world. Unfortunately, El Aleph presented a bit of a problem, as Dutton could not secure the translation rights for “Los teólogos,” “Deutsches Requiem,” “La busca de Averroës,” and “El Zahir.” Rather than publish an incomplete book, Dutton decided to produce a collection that would showcase a broader range of Borges’ fiction. The result was 1970’s The Aleph and Other Stories 1933–1969. Although the majority of its stories were taken from El Aleph, it was fleshed out with pieces from other sources, including new translations of “The Circular Ruins” and “Death and the Compass.” To round off the collection, Borges provided commentary on the stories, and the book ended with “An Autobiographical Essay,” a substantial piece written by Borges in English with the help of di Giovanni. Many of these new translations appeared in the New Yorker during this time, including the autobiographical essay, and over the next few years Dutton and di Giovanni helped cement Borges’ reputation in the United States.

The Aleph and Other Stories, 1933–1969 contains the following works:

- The Aleph

- Streetcorner Man

- The Approach to al-Mu’tasim

- The Circular Ruins

- The Life of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz (1829–1874)

- The Two Kings and Their Two Labyrinths

- The Dead Man

- The Other Death

- Ibn-Hakam al-Bokhari, Murdered In His Labyrinth

- The Man on the Threshold

- The Challenge

- The Captive

- Borges and Myself

- The Maker

- The Intruder

- The Immortals

- The Meeting

- Pedro Salvadores

- Rosendo’s Tale

- An Autobiographical Essay

- Commentaries

After the Dutton The Aleph and Other Stories 1933–1969 went out of print, American readers were forced to wait until 1998 for Viking’s Collected Fictions, which restored the original stories of El Aleph in new Hurley translations. In 2004, the Aleph stories were finally published as an individual book, Penguin Classic’s The Aleph and Other Stories—although a better title might have been Aleph and the Maker, as this 2004 edition also includes prose pieces from 1960’s El hacedor! Alas, Borges’ “Autobiographical Essay” has yet to be reprinted. That, along with Borges’ own commentary, makes finding a copy of Dutton’s The Aleph and Other Stories worth the effort.

El hacedor

The Maker / Dreamtigers

El hacedor

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1960

Online at: Internet Archive

Dreamtigers

By Jorge Luis Borges

Prose translations by Mildred Boyer, poetry translations by Harold Morland. Introduction by Miguel Enguídanos

University of Texas Press, 1964

Online at Internet Archive

The Maker

(Included in Collected Fictions)

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Andrew Hurley

Viking, 1998

Online at: Internet Archive

In the early 1960s, Borges had finally achieved international fame, and his works were being translated and published in French, English, Italian, and German. Unfortunately for his publishers in Argentina, Borges had not written any new books in several years. As Borges recalled to Richard Burgin in a 1967 interview:

I said “I haven’t any book.” And then my editor said to me, “Oh yes you have. If you go through your shelves or drawers you’ll find odds and ends. Maybe a book can be evolved from them.” So I think I remember it was a rainy Sunday in Buenos Aires and I had nothing whatever to do…so I thought I’ll look over my papers. Maybe I’ll find something in my drawers. I found cuttings, old magazines, and then I found that there was the book all ready for me.

That book was El hacedor. Four years later it was translated into English and published as Dreamtigers.

The contents of El hacedor are listed below. Every poem and narrative from El hacedor is found in Dreamtigers, but the English book does not contain the Spanish originals, in parallel text or otherwise. The thirty poems found in Viking’s Selected Poems are marked by asterisks, some which were published under different English titles. The prose pieces found in Viking’s Collected Fictions are marked by a plus sign (+), and may also have been given different titles. There are some pieces that have been duplicated, appearing in both volumes. Additionally, some of El hacedor’s parables appear in New Direction’s Labyrinths, which was published two years before Dreamtigers.

Part I

- A Leopoldo Lugones (“To Leopold Lugones”)*+

- El hacedor (“The Maker”)*+

- Dreamtigers*+

- Diálogo sobre un diálogo (“Dialogue on a Dialogue”)+

- Las uñas (“Toenails”)+

- Los espejos velados (“The Draped Mirrors”)+

- Argumentum ornithologicum+

- El cautivo (“The Captive”)+

- El simulacro (“The Sham”)+

- Delia Elena San Marco+

- Diálogo de muertos (“Dead Men’s Dialogue”)+

- La trama (“The Plot”)+

- Un problema (“A Problem”)+

- Una rosa amarilla (“The Yellow Rose”)*+

- El testigo (“The Witness”)+

- Martín Fierro+

- Mutations+ [Added to a later edition of El hacedor]

- Parábola de Cervantes y del Quijote (“Parable of Cervantes and Don Quixote”)*+

- Paradiso, XXXI, 108*+

- Parábola del palacio (“Parable of the Palace”)*+

- Everything and Nothing*+

- Ragnarök*+

- Inferno, I, 32+

- Borges y yo (“Borges and I”)*+

Part II

- Poema de los dones (“Poem about Gifts”)*

- El reloj de arena (“The Hourglass”)*

- Ajedrez (“The Game of Chess”)*

- Los espejos (“Mirrors”)*

- Elvira de Alvear

- Susana Soca

- La luna (“The Moon”)*

- La lluvia (“The Rain”)*

- A la efigie de un capitán de los ejércitos de Cromwell (“On the Effigy of a Captain in Cromwell’s Armies”)

- A un viejo poeta (“To an Old Poet”)

- El otro tigre (“The Other Tiger”)*

- Blind Pew

- Alusión a una sombra de mil ochocientos noventa y tantos (“Referring to a Ghost of Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Odd”)

- Alusión a la muerte del coronel Francisco Borges (1835–74) (“Referring to the Death of Colonel Francisco Borges”)

- In memoriam: A.R.

- Los Borges*

- A Luis de Camoens (“To Luis de Camoëns”)

- Mil novecientos veintitantos (“Nineteen Hundred and Twenty-Odd”)

- Oda compuesta en 1960 (“Ode Composed in 1960”)

- Ariosto y los árabes (“Ariosto and the Arabs”)*

- Al iniciar el estudio de la gramática anglosajona (“On Beginning the Study of Anglo-Saxon Grammar”)*

- Lucas, XXIII (“Luke XXII”)*

- Adrogué*

- Arte poética*

- Museo (“Museum”):

- Del rigor en la ciencia (“On Rigor in Science”)*+

- Cuarteta (“Quatrain”)*

- Límites (“Limits”)*

- El poeta declara su mombradía (“The Poet Declares His Renown”)*

- El enemigo generoso (“The Magnanimous Enemy”)*

- Le regret d’Héraclite (“The Regret of Heraclitus”)*

- In Memoriam J.F.K.+ [Added to the fourth edition of El hacedor, 1964]

- Epílogo (“Epilogue”)*

A beautiful collection of poems, meditative prose fragments, and unsettling parables, the pieces of El hacedor reflect their scattered origin, conjured from exile and suffused with the pensive melancholy of a rainy Sunday afternoon. (To borrow Borges’ description of his “Dreamtigers,” they seem “submerged and chaotic.”) A dreamy feeling of dislocation and impending revelation drifts through the entire collection, which is marked by surreal turns, ambiguous endings, and a vague sense of loss. Its peculiar format helped shape the remainder of Borges’ career, an eclectic convergence of poetry, prose, and parable that would find its most faithful successor in Atlas. It would be nearly a decade until Borges’ next collection of short stories, and those would have an entirely different tone; from this point on, Borges generally considered himself a poet.

Although Borges referred to El hacedor as a “crazy-quilt patchwork,” he considered the book to be his most intimate work, and his best. It contains numerous celebrated pieces, including “Borges and I,” “The Yellow Rose,” and “On Exactitude in Science.” It also features one of Borges’ most famous poems, “El otro tigre,” or “The Other Tiger.”

Note on the American Title

The most accurate translation of El hacedor is “The Maker,” but American editors were worried the term had overt religious connotations in English, and failed to capture the multiple valences of the Spanish title. A parallel of the Anglo-Saxon “Shaper” from Beowulf, El hacedor could certainly mean Creator, but was also meant to evoke Homer, Borges, and the mysterious act of creation itself. Instead, they named the collection after the third piece in the book, “Dreamtigers.” A mediation on the futility of the imagination to represent the real, “Dreamtigers” already possessed an English title, and seemed to embody the spirit of the book quite nicely. The modern Viking editions of Borges correctly refer to El hacedor as “The Maker,” but the title Dreamtigers is more frequently used—especially because Dreamtigers is still in print, and does considerably more justice to El hacedor than Viking, which only translates half the book and splits it across two volumes!

Additional Information

Dreamtigers is also detailed under the “Borges Poetry” section of the site, with a greater emphasis on its poetic contents. The entire text of Dreamtigers is available online at The Floating Library. You can read the 1969 revised edition of El hacedor in Obras completas 1923-1974, available online as an 1170-page PDF.

Antología Personal

Personal Anthology

Antología Personal

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Sur, 1961

Personal Anthology

By Jorge Luis Borges

Edited by Anthony Kerrigan, translations by Anthony Kerrigan, et. al.

New York: Grove Press, 1967

Online at Internet Archive

Published in the United States by Grove Press in 1967, Personal Anthology is exactly what the title declares—Borges personally selected these pieces was a showcase for his work. A combination of short stories, essays, and poetry, the pieces in Personal Anthology were arranged by Borges and Kerrigan to reflect “sympathies and differences” rather than chronological sequence. Personal Anthology bears a similarity to the later Labyrinths, but contains more poetry and fewer short stories.

- Foreword (by Anthony Kerrigan, Dublin, 1967)

- Prologue (by J. L. Borges, Buenos Aires, 16 August 16, 1961)

- Death and the Compass

- The Plot

- The South

- A Page to Commemorate Colonel Suarez, Victor

- The Dead Man

- Matthew 25:30

- Funes, the Memorious

- A New Refutation of Time

- Limits

- The Circular Ruins

- Chess

- The Golem

- Inferno I, 32

- The Other Tiger

- A Yellow Rose

- Baltasar Gracian

- To an Old Poet

- Parable of the Palace

- The Wall and the Books

- The Enigma of Edward Fitzgerald

- Ariosto and the Arabs

- Averroës’ Search

- A Soldier of Urbina

- The Maker

- Everything and Nothing

- From Someone to No One

- Forms of a Legend

- The Zahir

- The Aleph

- The Cyclical Night

- Allusion to a Ghost of the Eighteen-nineties

- The Tango

- Biography of Tadeo Isidoro Cruz

- The End

- Story of the Warrior and the Captive

- The Captive

- Paradiso XXXI, 108

- Luke 23

- The Witness

- The Modesty of History

- The Secret Miracle

- Conjectural Poem

- The Gifts

- The Moon

- The Art of Poetry

- Borges and I

- Poem Written in a Copy of Beowulf

- Editor’s Epilogue: An exchange of letters between Anthony Kerrigan and Alastair Reid

Labyrinths

Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings By Jorge Luis Borges Translated and edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. Introduction by André Maurois. New York: New Directions, 1962 Online at Internet Archive |

Labyrinths [Revised] By Jorge Luis Borges Translated and edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. Introduction by William Gibson New York: New Directions, 2007 Online at Internet Archive |

Published the same year as Grove Press’ translation of Ficciones, New Direction’s Labyrinths was instrumental in establishing Borges’ reputation in the United States, and was many Americans’ first introduction to Borges. Edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby, Labyrinths gathers together thirteen stories from Ficciones, ten stories from El Aleph, ten essays from Discusión and Otras inquisiciones, and eight “parables” from El hacedor. The stories from Ficciones are different translations from those published by Grove Press, which makes the collection essential for any Borges completist. Along with Yates and Kirby, additional translators included Anthony Kerrigan, L.A. Murillo, Dudley Fitts, John M. Fein, Harriet de Onás, and Julian Palley. The contents are as follows:

Fictions

- Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

- The Garden of Forking Paths

- The Lottery in Babylon

- Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote

- The Circular Ruins

- The Library of Babel

- Funes the Memorious

- The Shape of the Sword

- Theme of the Traitor and the Hero

- Death and the Compass

- The Secret Miracle

- Three Versions of Judas

- The Sect of the Phoenix

- The Immortal

- The Theologians

- Story of the Warrior and the Captive

- Emma Zunz

- The House of Asterion

- Deutsches Requiem

- Averroes’ Search

- The Zahir

- The Waiting

- The God’s Script

Essays

- The Argentine Writer and Tradition

- The Wall and the Books

- The Fearful Sphere of Pascal

- Partial Magic in the Quixote

- Valéry as Symbol

- Kafka and His Precursors

- Avatars of the Tortoise

- The Mirror of Enigmas

- A Note on (toward) Bernard Shaw

- A New Refutation of Time

Parables

- Inferno, I, 32

- Paradiso, XXXI, 108

- Ragnarök

- Parable of Cervantes and the Quixote

- The Witness

- A Problem

- Borges and I

- Everything and Nothing

- Elegy (Added in 1964)

The original 1962 edition of Labyrinths borrowed a French preface from the colorful writer André Maurois, and featured an introduction by editor and translator James E. Irby. The 1964 “augmented” edition added a short chronology of Borges’ life, and concluded with the poem “Elegy.” In 1984, a hardcover edition was published by the Modern Library. In 2007, New Directions finally revised Labyrinths. They updated the chronology, “corrected” the original translations, and replaced Maurois’ preface with an “invitation” penned by science-fiction writer William Gibson. They also changed the cover for the first time since John F. Kennedy was president. (I’m actually a bit disappointed by that extravagance, but at least the cover remains black and white!)

Labyrinths was designed as an introduction to Borges, and nearly sixty years later, in remains an ideal place for the beginner to start.

El informe de Brodie

Doctor Brodie’s Report

El informe de Brodie

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1970

Online at: Internet Archive

Doctor Brodie’s Report

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Norman Thomas di Giovanni

New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972

Online at Internet Archive

Brodie’s Report (Included in Collected Fictions) By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Viking, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

Brodie’s Report By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Penguin Classics, 2005 |

Originally published as El informe de Brodie on 7 August 1970, these stories were written in the late 1960s in loose collaboration with Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Surprisingly removed from the mind-bending tales of fabulism found in Ficciones and El Aleph, with few exceptions—the most notable being the title story, fashioned after Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels—these stories return to the obsessions of Borges’ youth, and conjure a vanished Argentina populated by gauchos, fallen women, tango dancers, and knife-fighting compadritos. All the usual suspects are here, but depicted with more irony and distance than the younger Borges brought to his “fevers” of Buenos Aires.

The original Spanish edition contains the following stories, presented here with their Hurley titles:

- Foreword (by Borges and di Giovanni, Buenos Aires, 29 December 1970)

- The Interloper

- Unworthy

- The Story from Rosendo Juárez

- The Encounter

- Juan Muraña

- The Elderly Lady

- The Duel

- The Other Duel

- Guayaquil

- The Gospel According to Mark

- Brodie’s Report

The first English translation was produced by E.P. Dutton. As with The Aleph and Other Stories, Norman Thomas di Giovanni worked closely with Borges in Buenos Aires to collaborate on translations. As Borges remarks in his foreword, the writing and translation were essentially simultaneous, producing a set of translations born from the same “mood” as the stories themselves. The titles of the Dutton edition—which names the book Doctor Brodie’s Report—are as follows:

- Foreword (by Borges and di Giovanni, Buenos Aires, 29 December 1970)

- Preface to the First Edition (by Borges, Buenos Aires, 19 April 1970)

- The Gospel According to Mark

- The Unworthy Friend

- The Duel

- The End of the Duel

- Rosendo’s Tale

- The Intruder

- The Meeting

- Juan Muraña

- The Elder Lady

- Guayaquil

- Doctor Brodie’s Report

- Afterword (by Borges, Buenos Aires, 29 December 1970)

- Bibliographical Note

This Dutton translation was acquired in the UK by Allen Lane/Penguin, and an Allen Lane UK version came out in 1974. In 1976 it was copyrighted by Penguin, which kept the British book in circulation long after the American original slipped out of print. In 1998 Andrew Hurley produced a new translation for Viking’s Collected Fictions, dropping “Doctor” from the title. In 2005, Hurley’s translation of Brodie’s Report was published as an individual book by Penguin Classics.

El libro de arena

The Book of Sand

El libro de arena

By Jorge Luis Borges

Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1975

Online at: Internet Archive

The Book of Sand

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translations by Norman Thomas di Giovanni and Alastair Reid

New York: E. P. Dutton, 1977

Online at: Internet Archive

The Book of Sand (Included in Collected Fictions) By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Viking, 1998 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory By Jorge Luis Borges Translation by Andrew Hurley Penguin Classics, 2007 |

Originally published in 1975, the original Spanish edition contains the following stories, presented here with their 1999 Hurley titles:

- The Other

- Ulrikke

- The Congress

- There Are More Things

- The Sect of the Thirty

- The Night of the Gifts

- The Mirror and the Mask

- “Undr”

- A Weary Man’s Utopia

- The Bribe

- Avelino Arredondo

- The Disk

- The Book of Sand

- Afterword (by Borges, Buenos Aires, 3 February 1975)

The English version of this collection was published by E.P. Dutton, with Norman Thomas di Giovanni doing the accustomed translation. Oddly, the Dutton edition included “The Gold of the Tigers,” a section of poetry culled from El oro de los tigers and La rosa profunda and translated by Alastair Reid. The titles of the Dutton edition follow the original, although di Giovanni renders the title of the ninth story more poetically as “Utopia of a Tired Man.”

The story “There Are More Things” is dedicated “To the memory of H.P. Lovecraft,” and is generally considered an interesting but ultimately unsuccessful Lovecraft pastiche.

The Dutton edition was published in England by Allen Lane/Penguin in 1979. In 1998 Andrew Hurley produced a new translation for Viking’s Collected Fictions. In 2007, Hurley’s translation of The Book of Sand was bundled with four late Borges stories and published as The Book of Sand and Shakespeare’s Memory by Penguin Classics. Previously only available in Viking’s Collection Fictions, these stories had originally appeared in the Spanish-only Obras Completas 1975-1985. They include “August 25, 1983,” “Blue Tigers,” The Rose of Paracelsus,” and Borges’ final story, “Shakespeare’s Memory.”

The Library of Babel

The Library of Babel

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translation by Andrew Hurley

Illustrations by Erik Desmazieres

Boston: David R Godine, 2000

An illustrated version of Borges’ short story “The Library of Babel” from Ficciones.

Everything and Nothing

Everything and Nothing

By Jorge Luis Borges

Translations by Donald A. Yates, James E. Irby, & Eliot Weinberger

New York: New Directions, 1999

As with Viking’s Collected Fictions, the release of Everything & Nothing coincided with the Borges Centennial. It’s a fairly modest book, collecting some of Borges’ best-known stories and essays. Hardly essential, it makes one wonder why New Directions didn’t take the opportunity to publish an updated, revised and expanded version of Labyrinths instead.

- Introduction (by Donald A. Yates)

- Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote

- Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius

- The Lottery in Babylon

- The Garden on Forking Paths

- Death and the Compass

- The Wall and the Books

- Kafka and his Precursors

- Borges and I

- Everything and Nothing

- Nightmares

- Blindness

Borges Works

Main Page — Return to the Borges Works main page and index.

Nonfiction — Collections of essays and criticism.

Collaborations with Bioy Casares — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Collaborations with Others — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with others.

Poetry Compilations — Selections of Borges’ verse translated into English and published as compilations.

Poetry I — Early post-ultraísmo poetry, 1923 to 1943.

Poetry II — Mid-career collections from 1944 to 1969.

Poetry III — Late poetry books from 1969 to 1985.

Lectures, Conversations, and Interviews — Collections of Borges’ lectures, conversations, and interviews.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 26 July 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Rodigo

It is good to read about fiction and poetry, but unfortunately here in Brazil they do not value reading very much, especially in relation to fiction. Until a little while ago, I didn’t know Borges.

Congratulations! Interesting text!