Borges – Biographies

- At October 13, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

To think of him is to think of an intimate friend, one we have never seen but whose voice we know and every day miss.

—Jorge Luis Borges on Oscar Wilde, Atlas, 1984

Borges Biographies & Memoirs: Biographies

This page profiles English-language biographies of Borges. They are listed in chronological order of publication. Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

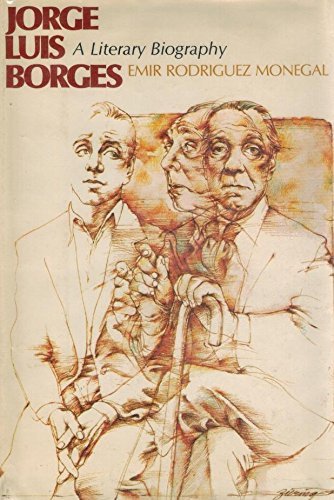

Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography

Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography

By Emir Rodríguez Monegal

Paragon House, 1978

Online at: Internet Archive

Emir Rodríguez Monegal was a Uruguayan writer, editor, and critic, the founder of numerous Hispanic literary magazines, and a powerful advocate for Latin American writers in North America. Published in 1978, Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography was the first major biography of Borges available in English, and remained “the” Borges biography for nearly twenty years.

Monegal’s biography has much to recommend it, and his position as a literary critic is evident in his insightful discussions of Borges’ writing. However, many have complained of factual inaccuracies—modern Borges scholars have cited over sixty errors—and Monegal’s style is often dry and pedantic. He is fond of projecting his own theories into his subject, a disagreeable approach that feels like amateur psychoanalysis. (Fellow Borges biographer James Woodall correctly called the book “humorless.”) Despite its flaws and idiosyncrasies, Jorge Luis Borges: A Literary Biography remains an indisputably important work, and all modern Borges scholarship is indebted to Monegal.

Hispanics of Achievement: Jorge Luis Borges

Hispanics of Achievement: Jorge Luis Borges

By Adrian Lennon

Chelsea House, 1992

Online at: Internet Archive

Part of an educational series produced for U.S. school libraries—hence the patronizing title—Lennon’s slim biography is surprisingly charming, filled with photographs and amusing illustrations. As one might expect from a book intended for students, Lennon writes in a simple, direct style; sticking to the basic facts, avoiding critical judgments, and maintaining an upbeat tone. Nevertheless, he makes good use of the format, and his cheerful enthusiasm keeps the pages turning. (An author of mystery novels, Lennon is also an engaging wordsmith; this book is actually a “good read.”) In short, Lennon’s Jorge Luis Borges makes a handsome introduction to Borges for students, their parents, or curious chemistry teachers passing the library bookshelf.

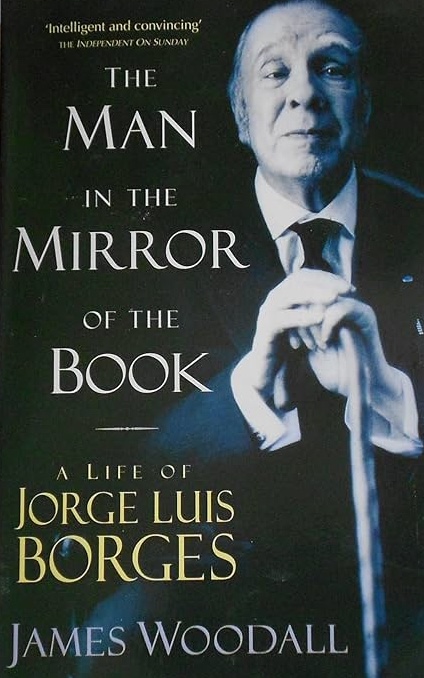

The Man in the Mirror of the Book

a.k.a. Borges: A Life

The Man in the Mirror of the Book By James Woodall Hodder & Stoughton 1996 |

Borges: A Life By James Woodall Basic/HarperCollins 1996 Online at: Internet Archive |

The 1990s were a fascinating decade for Borges scholarship. Borges himself had only recently died, leaving his estate in the hands of his young widow, María Kodama. His 100th birthday was right around the corner, and the publishing word was preparing to honor the Borges Centennial with a rich slate of new translations. His musical collaboration with Astor Piazzolla, El tango, was re-recorded, and the explosive growth of the Internet resulted in numerous Borges web sites, including The Garden of Forking Paths. There was a Borges renaissance afoot; and while lacking the excitement of discovery that marked Borges’ emergence onto the international stage in 1961, it certainly cemented his posthumous reputation as one of the great twentieth century writers. Who needed a Nobel Prize when you had become a global phenomenon?

This renaissance called for an updated biography. First published in the U.K. as The Man in the Mirror of the Book, James Woodall’s study of Borges is an attempt to make a “considerable improvement” upon Monegal’s Borges: A Literary Biography. In his introduction, Woodall compares Monegal’s work to Herbert Gorman’s seminal biography of James Joyce, an early attempt to capture Joyce’s life. Important but deeply flawed, Gorman’s book was eventually replaced by Richard Ellmann’s masterpiece, James Joyce. Given Woodall’s comparison—and it’s a fair one—the reasonable question arises, does Woodall’s biography stack up to Ellmann’s?

As Woodall himself would probably agree, the answer is “no.” While Borges: A Life is a solid biography, it’s not aiming for the sheer completeness of Ellmann’s James Joyce, let alone critically-acclaimed works like Caro’s epic on Lyndon B. Johnson, Joshi’s minute-by-minute reanimation of H.P. Lovecraft, or Parker’s generous study of Herman Melville. Borges: A Life is a well-written and enjoyable “one volume” biography intended for the average reader. Woodall keeps his personal thoughts to a minimum, rarely offering interpretations of Borges’ writing and refraining from the amateur psychoanalysis biographers often find irresistible. Woodall keeps his focus on Borges’ life and the reception and impact of his work.

Borges: A Life is not without its detractors. Critics have found numerous faults with Woodall’s work, from nit-picking the absence of this or that influence on Borges’ style to the more serious accusation that Woodall misunderstands Borges’ place in Hispanic literature. Personally, I find myself frustrated by his lack of literary analysis, and wish Woodall would have gone deeper into Borges’ texts. The most prevalent critique is the biography’s lack of color and detail; scanning contemporary reviews, adjectives like “serviceable,” “solid,” and “straightforward” make frequent appearances.

These are valid criticisms; but it remains important to consider the time in which Woodall was doing his research. Following Borges’ death, the state of Borges scholarship was rife with discord and controversy—much original material remained scattered, whether in the hands of private collectors or jealously guarded by friends and relations. At the center of this controversy was María Kodama, who maintained a famously tight hold on the Borges estate until her death in 2023. Writing a comprehensive Borges biography is no simple task, and among other things, it would have required Kodama’s complete cooperation. Although she agreed to be interviewed for Woodall’s book, she declined to grant it “authorization,” nor would she provide a blurb or any form of recommendation. Simply put, Kodama denied Woodall the resources he needed as a professional biographer.

Woodall’s trials with Kodama are the focus of the book’s “Afterword,” and make fascinating reading, if occasionally suggesting the tart smack of sour grapes. (The Economist accused him of “sulking.”) However, it is not cynical to mention that soon after The Man in the Mirror of the Book was published, another Borges biography hit the shelves, Edwin Williamson’s Borges: A Life. Published by Viking, a company with a long association with Borges, Williamson had the full support of María Kodama, and several critics have noted that his biography presents her in a rather positive light. The situation is further complicated by the names of the two biographies. When The Man in the Mirror of the Book was published in the United States and Canada in 1996, it was retitled as Borges: A Life. Why Williamson’s biography confusingly adopted that same name in 2004 is open to speculation.

As of today, Woodall’s Borges: A Life is one of three significant Borges biographies available in English. Standing between Monegal’s flaws and Williamson’s peculiarities, Woodall’s book splits the difference in terms of length, breadth, and depth. For the general Borges enthusiast, this gives Woodall’s readable biography a Goldilocks appeal—Borges: A Life may be “just right.”

Borges: A Life

Borges: A Life

By Edwin Williamson

Viking, 2004

Online at: Internet Archive

The Borges Centennial of 1999 was the culmination of a decade that saw a significant increase in Borges scholarship across the world, from the foundation of Borges-related organizations to the release of Viking’s new translations. This renaissance called for an updated Borges biography, and two writers stepped forward to fulfill that task for the English-speaking world. The first was James Woodall, who published The Man in the Mirror of the Book, reviewed above. The second was Edwin Williamson, who published Borges: A Life several years later.

Of the two, only Williamson, a professor at Oxford University, obtained the full cooperation of María Kodama, Borges’ widow and executor. Denied this access, Woodall produced an enjoyable but simple book, one that adhered to the facts, but was accused of frequent omissions and misunderstandings. Williamson’s biography, however, is quite a different affair. Longer and more intensely researched than Woodall’s book of the same name, Williams Borges: A Life doesn’t merely provide additional details, it attempts to psychoanalyze Borges and explain the hidden meanings behind his writing. Williamson’s biography portrays Borges’ life as a Freudian journey passing through multiple stages of romantic and sexual frustration, only to achieve a kind of loving redemption at the conclusion.

This narrative is both the strength and weakness of the book. On one hand, Borges himself becomes a literary character in his own right, and the reader finds it easy to sympathize with his ups and downs. The reader is given an “origin story”—Borges is born in a library, the product of an absent father and an overbearing mother. This compelling character proceeds to a life of heartbreak and disillusionment. A “mama’s boy” unable to engage with mature women, he lives his fantasies through the vivid dreamworlds of fiction, caught between the “illicit dagger” of his father and the “ancestral sword” of his mother. (No, really—“the conflict rooted in his childhood between the ancestral sword, associated with Mother, which conferred honor, distinction, legitimacy, and the dagger, associated with Father, which symbolized the illicit energy of excluded desires.”) Only upon the death of his mother does Borges find redemption, breaking his “psychological fetters” and finally embracing the healing power of love. And that love is naturally María Kodama.

While this narrative makes a gripping read, it occasionally elides Borges’ own statements and opinions as expressed in numerous interviews and essays. As some critics of the book have noted, Williamson is reluctant to offer primary sources, and spends much time paraphrasing, speculating, and suggesting ulterior motives. Like many writers with a Big Idea, Williamson attempts to fit every detail into his ideological framework. (As the German writer Björn Quiring has remarked, “Save me from a curator with an idea.”) Sometimes this approach pays off, as when Williamson contextualizes Borges’ fraught relationships with Estela Canto and Norah Lange. At other times it feels like academic B.S., such as his appraisal of “The Aleph”—“The Aleph would come to represent an abiding aspiration to achieve a unity of being in which the self could be fully realized yet integrated in the objective reality of the world.” At his worst, Herr Doktor Williamson robs Borges of agency, transforming him into a Freudian puppet of subconscious forces—“…this story addresses Borges’s old anxieties about being a coward… He was caught in his double bind once more, paralyzed by his instinctive reluctance to submit to his mother, yet bereft of any faith in his own capacity to rebel.”

The enjoyment one is likely to obtain from Borges: A Life can be predicted by one’s response to these excerpts. Readers who go in for that sort of psychological drama will certainly find the book more palatable than those who prefer a less obtrusive biographer. (As for myself, I thoroughly enjoyed the book, but shook my cranky fist at Williamson on more than once occasion!) Curiously, Williamson displays little interest in Borges as a writer, and readers expecting to learn more about the “stories behind the stories” will be sorely disappointed. Too many important works are produced out of thin air, with Williamson clearly more interested in their psychological import than their literary impact.

Borges: A Life works best when Williamson sets aside his psychoanalysis and explores the cultural and political nuances of the period. His descriptions are always vivid, and he depicts pre-War Buenos Aires with a palpable excitement, whether following the literary feuds sparked by the spirited bohemians at Martín Fierro or unraveling the internecine entanglements of Borges’ many friends and associates. Williamson is an astute commentator on politics, and his analysis of Borges’ political development is a strength of the book praised by numerous reviewers.

Edwin Williamson’s Borges: A Life is extremely well-written and always interesting; but the intense focus he brings to Borges’ environment blurs when it falls upon Borges himself. Ultimately, each reader must decide how much weight to assign Williamson’s psychological interpretations. But until something better comes along, Borges: A Life stands as the most complete Borges biography available in the English language.

Jorge Luis Borges

(Critical Lives Series)

Jorge Luis Borges

By Jason Wilson

Reaktion Books, 2006

This slim, 150-page biography of Borges was published in 2006, following closely in the wake of James Woodall’s The Man in the Mirror of the Book and Edwin Williamson’s Borges: A Life. Part of Reaktion Book’s “Critical Lives” series, Jorge Luis Borges is designed for readers looking for a shorter read than Woodall or Williamson’s more comprehensive biographies.

This is an admirable goal; but Jorge Luis Borges suffers from several critical flaws. The first is Wilson’s inability to maintain a coherent narrative. The chapters are laid out in chronological order: Borges’ birth and childhood in Buenos Aires, his adolescence in Geneva, his enthusiastic return to Argentina, the avant-garde years, his middle-aged success, and finally his twilight years and death. And while Wilson follows this overall arc, each chapter is riddled with disorienting jump-cuts and cross-references. One moment Borges is a child in Palermo; the next we’re offered his mature insights and reflections on the local color; then he’s whisked to Geneva for a few sentences before being quickly returned to Argentina—all in the same paragraph. One gets the impression that Wilson has adopted a Tralfamadorian point of view, observing the 4-D complexity of Borges’ life and drawing cross-connections as they occur to him. This may be fine for readers already familiar with Borges’ biography; but for those who haven’t read Woodall or Williamson, the result is a tangled narrative that frustrates the ability to construct a linear sequence where point A leads to point B and thence logically to C.

Perhaps appropriately, this is best illustrated by Wilson’s discussion of “The Aleph.” Identified by Wilson as the short story most critical to understanding Borges himself, “The Aleph” is first mentioned on page 23 during the discussion of Borges’ parents and last mentioned on page 145 when Borges is near death. The story is referred to again and again, each time Wilson describing how some facet relates to Borges’ private life—it’s “sexy dedicatee” Estela Canto, the possible inspirations for Beatriz Viterbo and Carlos Argentino Daneri, the story’s physical location, Borges’ depression, disillusionment, and insomnia, and so on. Unfortunately, the plot of “The Aleph” is never coherently described, its details doled out in piecemeal fashion across the narrative. Borges doesn’t even “write” the story until page 126, at the end of the book’s penultimate chapter. While there’s some ironic value in unfolding “The Aleph” across the entirety of Borges’ life, even a reader familiar with the story may find himself confused by the haphazard way Wilson introduces and dispatches characters and themes. And that’s just one example.

This chronological disorder results in much awkward signposting throughout the narrative. Borges’ infamous “accident” is mentioned numerous times before it occurs. María Kodama is introduced as someone the reader should already know. Borges’ various unrequited loves are shuffled around with little differentiation or context. Besides making the narrative needlessly convoluted, this asynchronous approach drains the biography of dramatic impact. We already know so many things about the “future” Borges that when these events finally occur in the “present” the reader often thinks, “Wait, didn’t this already happen?”

Wilson’s fondness for convolution extends to his writing style. Sentences that begin on one subject take bizarre twists to land elsewhere, resulting in clumsy constructions that feel like poor translations. This sense of awkwardness is compounded by puzzling word choices. For instance, we read that “Their public feud was definitive when Martínez Estrada later supported the 1959 Cuban revolution (and travelled there to write about it.).” Was definitive? Or, “To test if this accident had affected his mind and left him witless, Borges stumbled onto a new kind of short story that compacted his book-reviewing and essays with the kind of stories Edgar Allan Poe wrote.” The word “stumble” implies serendipity or accident, not design. You do not test something by stumbling; although stumbling onto something new might be a result of that test. (Not to mention the inelegance of “witless” and “compacted.”) Wilson also relies too much on parentheses, overloading his sentences with asides, extensions, and afterthoughts. At one point in Jorge Luis Borges I counted 9 out of 12 sentences in a row that contained parenthetical expressions!

Overall, Jorge Luis Borges reads like a first draft in need of an editor; an impression only confirmed by its numerous errors. The Nobel Prize is referred to as the “Noble Prize.” The much-abused word “literary” is used incorrectly. Wilson claims that Labyrinths was the English title for the translation of El Aleph, when in fact it was a compilation of Borges’ work. The book also contains several typos.

There are more problems with Jorge Luis Borges than its convoluted structure and writing style. Like too many biographers, Wilson appoints himself as his subject’s psychoanalyst. Yes, Wilson met Borges “briefly and formally” several times. But this hardly gives him license to make authoritative claims, and he frequently reduces psychological complexities to simple, cause-and-effect relationships: this particular thing happened to Borges, which explains that exact personality trait or literary response. While Wilson’s desire to “place his subject on the couch” is not as obnoxious or pervasive as Edwin Williamson’s, Wilson sees Borges as a sexually inept “mama’s boy” who suffered from crippling depression and sexual dysfunction, a reading he applies mechanically to explain most of Borges’ writing. (He even wonders if Borges was “a masturbator,” whatever that means!) There’s also Wilson’s tendency to make totalizing statements with little supporting evidence. For instance, here’s the conclusion he draws from a young Borges encountering Ulysses:

Argentine avant-garde writing was tepid compared to Joyce. No academic distance in any of Borges’s reading; in fact, a kind of transference, an identity of reading. Borges became Joyce.

No, Borges most certainly did not become Joyce—except in the broad, Borgesian sense that any reader “becomes” the writer he’s currently reading. Borges never completed Ulysses, and expressed mixed feelings about Finnegans Wake. While assertions like this abound throughout Jorge Luis Borges, Wilson’s own “transference” with his subject reaches its peak when he parenthetically intrudes on a discussion of “Death and the Compass” with this editorial comment:

(that ‘interminable’ is a typically odd Borgesian adjective; I’d have written ‘pervasive.’)

Well, I’m glad to know that…?

The few successes of Jorge Luis Borges are modest, but commendable. Despite his flaws as a biographer, Wilson clearly knows his subject. The book is strongest when discussing Borges’ relationships with his friends and rivals, especially those figures underserved by previous biographers—Carlos Mastronardi, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Leopoldo Marechal, Alberto Hidalgo, etc. The chapter on Borges’ youthful life in the literary cafes of Buenos Aires is the best part of the book. It’s clearly the period of Borges’ life that holds the most interest to Wilson, and these pages sparkle with witty observations and insightful commentary about the nature of intellectual friendships and rivalries. It’s the only point in the biography that Borges emerges as something other than a self-loathing figure in the midst of a depression.

Borges’ main creative period is reserved for the biography’s penultimate chapter. The classic stories are discussed briefly, including “Pierre Menard,” “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” “The Library of Babel,” “The Zahir,” and of course “The Aleph.” Wilson tends to focus on the personal aspects of these stories, seeing them as “dark and nightmarish” allegories of Borges’ miserable life leavened by occasional bursts of self-deprecating humor. And while there’s obviously some truth to this, Wilson rarely places them in any broader context. There’s no real discussion about why these stories are so groundbreaking, or what impact they had on the literary world. A casual reader may be left to wonder at Wilson’s later remark that The Garden of Forking Paths was “the most revolutionary book ever published in Argentina, possibly in Spanish.” It’s like focusing on Kafka’s estrangement from his father in “The Metamorphosis” without mentioning that Gregor Samsa turned into a monstrous insect.

The biography quickly loses interest in Borges after he goes blind in the late 1950s. The Formentor Prize is mentioned, but undervalued in terms of impact, and El Hacedor is virtually dismissed—though Wilson takes a peculiar dig at the “foolish” U.S. title of Dreamtigers. Borges’ life between 1955 and 1986 is covered in 18 pages, a series of skipping stones flicked across three decades: Borges’ first marriage, his friendship with Norman Thomas di Giovanni, the latter stories and poetry, some travel, his relationship with María Kodama, his death in Geneva.

All in all, Jason Wilson’s Jorge Luis Borges is a disappointing and inadequate work, inelegantly written and poorly edited. While the chapters on Borges’ early life among the cafés of Buenos Aires are worth reading, newcomers looking for a short biography of Borges may come away more confused than enlightened.

Borges

Borges By Adolfo Bioy Casares Destino, 2009 Online at: Internet Archive |

Borges By Adolfo Bioy Casares Introduction by Alberto Manguel Translation by Valerie Miles New York Review of Books, 2025 |

Soon to be translated into English by Valerie Miles, this massive biography of Borges was written by his friend and collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares. Garden editor Gabriel Mesa provides the following comments on the original Spanish-language publication:

At almost 1700 pages, Borges is a massive tome composed of those extracts from the diaries of Adolfo Bioy Casares that feature Jorge Luis Borges. The fact that Bioy Casares kept a diary for over fifty years and that he and Jorge Luis were best friends, with Borges dining at his house several times a week, explains the gargantuan amount of material. Bioy Casares worked with editor Daniel Martino to prepare the book for publication beginning in 1996, but was not able to see it in print before he died in 1999. Borges was not published until September of 2006, fully seven years later.

Borges in substantial part consists of a detailed recounting of the hundreds of conversations between Borges and Bioy Casares over the years, most of which happened over dinner. As a result, they are literally “table talk.” Bioy Casares writes on January 12, 1948, “Borges come en casa” (“Borges dines at [our] home”), and this sentence or some variation thereof will be repeated dozens of times over the coming years. (Famous diaries all seem to have their own repetitive mantra—witness Pepys’ “And so to bed.”) For those wondering how Bioy Casares kept such close recall over what Borges said at each encounter, the answer is that he took notes, dutifully recording Borges’ bon mots, ideas, impressions and opinions, positive or negative. It is clear that from the beginning Bioy Casares had an eye to recording these entries for posterity; the intimate portrait of a great man, as revealed in writing by his closest friend. The parallel to Boswell and Johnson is no accident; Bioy Casares himself translated Boswell’s Life of Johnson into Spanish, no mean task.

Much of the delight of Borges lies in hearing Jorge Luis and Bioy Casares openly opine and gossip about everything (and everyone) under the sun. They are very critical, very pointed and very funny, although (for the most part) not unkind. Most of their arrows are aimed at fair targets—coddled Argentine high society ladies, vain and untalented writers, pompous critics and so on. A description of one entry may be sufficient to convey the flavor:

On June 18, 1956, Borges dines at chez Casares. They do not dine alone, however, but in the company of the Cuban novelist Virgilio Piñera (Rene’s Flesh, Cold Stories), the Argentine writer Rodolfo Wilcock (The Temple of Iconoclasts) and two others. There is a discussion about Bioy Casares’ reluctance to lecture in public. Borges muses on the difference between a private conversation and a lecture, observing that it is in the nature of a conversation for the participants to seek to “apoderarse del silencio” (“control the silence”). There follows a conversation about ignorant Argentine writers, with anecdotes. Borges tells the story of one writer who read some novels by Dickens and couldn’t stop telling everyone about it; when he started mentioning their titles another writer took out his notebook and dutifully began writing them down. Borges finds this hilarious. Reference is also made to another writer, a poet who numbered every five of his verses, apparently because he once saw it done in a book of poems by Luis Góngora, not realizing that this was not an affectation of Góngora’s but a simple reading aid inserted by the book’s publisher. The conversation then turns to literary matters, with Piñera voicing an appreciation of H.P. Lovecraft, indicating that he is “superior to Bradbury, the Poe of his time.” After the other guests have left, Borges begs to differ, noting to Bioy Casares that Lovecraft is “cheap,” and that “the Poe of our time, or the Dostoyevsky of our time, if any, are not writers that imitate or are similar to Poe or Dostoyevsky. They will have to be original and extraordinary writers, not facsimiles of anybody.” All this in one evening, with much left out.

A word of caution—as with all diaries, Bioy Casares’ is a reflection of its time and employs language at times that today we would find offensive. For example, from the above description of the 1956 entry I left out the fact that Bioy Casares knows Virgilio Piñera and his companion to be homosexual, and uses very crude wording to describe their sexual orientation. That said, it is worth remembering that Buenos Aires in the 1950s would have been a very homophobic environment; the fact that Bioy Casares invited two gay men to dine at his house is an indication of a more tolerant outlook. Also hard to square with modern mores is the omission (with a few exceptions) of Silvina Ocampo from the diaries—she was not only Bioy Casares’ wife, but a talented author in her own right, and an important collaborator of Borges’, as well as being (one imagines) responsible for the meals Borges ate every night at her house. The oversight is unfortunate and leaves a sour taste.

María Kodama became famously irate at the publication of Borges, incensed at the fact that Bioy Casares was revealing private conversations in which Borges spoke disparagingly of other writers. Her reference to Bioy Casares, in a 2012 interview in Manhattan, as “Borges’ Salieri” resulted in a significant outcry by the Argentine literary establishment, who felt Bioy Casares was being unfairly maligned. That said, Kodama’s concerns are understandable. In the very same diary entry discussed above, Borges and Bioy Casares speak disparagingly of Ernesto Sabato (The Tunnel) and make fun of his having proclaimed himself the “Argentine Dostoyevsky” after having read Crime and Punishment. Borges then pronounces The Tunnel “slight.” It is worth remembering that Borges and Sabato engaged in a wonderful series of dialogues 18 years later that were published as Diálogos in 1976. It is unknown whether Sabato ever knew of this comment, but it’s also not clear that it matters much anymore, especially when you consider that nearly all of the people Borges and Bioy Casares gossiped about until Borges’s death over 30 years ago have likely passed away themselves. And whatever indiscretions Borges may have committed, one assumes he did so in the full knowledge that Bioy Casares was not only acting as his friend and interlocutor but also as a faithful scribe.

Borges contains a 64-page glossary of proper names with short descriptions of the individuals mentioned in the diaries but, alas, no index—an unforgivable omission hopefully corrected in a subsequent edition.

Georgie & Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife: The Untold Story

Georgie & Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife: The Untold Story

By Norman Thomas di Giovanni

The Friday Project, 2014

This biography was written by Borges’ celebrated English-language translator, collaborator, and friend, Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Despite this friendship—or perhaps because of it—Georgie & Elsa is not the expected fond memoir, but a searing tell-all that portrays Elsa as a vain and shallow “bitch,” Borges’ mother as a controlling harridan, and Borges as an impotent mama’s boy whose marriage was an “inexplainable and mysterious mistake.” Di Giovanni himself is cast in the role of Borges’ accomplice, the best friend who helps the hapless writer extract himself from the disastrous relationship.

Although Norman Thomas di Giovanni has a reputation for being flinty, it’s still a surprise to encounter such harsh descriptions and unflattering portraits of Borges and his inner circle. The book centers on Borges’ awkward relationship with Elsa, but it’s not difficult to detect the looming presence of Borges’ second wife, María Kodama, who was rarely on good terms with her husband’s old friends. After Kodama took control of the Borges estate, she severed ties with Norman Thomas di Giovanni, forcing his translations out of print and terminating his most lucrative stream of revenue.

Not a few critics have wondered if the unsavory tang of Georgie & Elsa is not the aftertaste of this sour relationship. Still, some critics have praised its forthrightness, such as Carlo Gébler, who applauds di Giovanni for providing “a real corrective to the Borges industry and the nonsense that industry promulgates.”

From the publisher, an imprint of HarperCollins:

Jorge Luis Borges, known as Georgie to his friends, married Elsa Astete Millán in 1967. Borges was sixty-eight years old at the time of the wedding; Elsa, a widow, with a son in his twenties, was eleven years younger. It proved to be a tempestuous and eventful marriage that would leave an indelible mark on the remainder of Borges’ life, but their relationship has been largely glossed over by previous biographers. This is because the one person who knew all the details has refused to speak about it.

Until now.

Norman Thomas di Giovanni worked with Borges in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in Buenos Aires from late 1967 to 1972 and thereafter sporadically until Borges’s death in 1986. During their first period together di Giovanni spent more time with the couple than did almost anyone else. He was privy to the private side of their relationship and to its sudden decline. It was di Giovanni who helped the demoralized Borges by organizing and arranging his divorce and at the same time rescuing his library and smuggling him out of Buenos Aires to avoid the wrath of Elsa and her lawyers.

The book is based on the author’s extensive collection of original material in the form of diaries, notebooks, letters, manuscripts, and photographs, most of which has never before been seen. It provides a unique insight into one of the few true geniuses of literature.

Borges Biography & Memoir

Main Page — Return to the Borges Biography & Memoir main page and index.

Biographical Sketch — The Garden’s biographical sketch on Borges.

Borges Memoirs — This page details memoirs about Borges by his friends and associates.

Authors: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 3 December 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com