Borges Collaborations

- At July 31, 2018

- By Great Quail

- In Borges

0

0

This felicitous supposition declared that there is only one Individual, and that this indivisible Individual is every one of the separate beings in the universe, and that these beings are the instruments and masks of divinity itself.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”

Borges Works: Collaborations with Others

Borges enjoyed collaborating with other writers, translators, and artists. He began his career by translating Oscar Wilde, helped his father write a historical novel named El Caudillo, and worked closely with his sister Norah to illustrate his early poems. He produced dozens of works with Adolfo Bio Casares, some including Silvina Ocampo and Xul-Solar. Borges frequently struck up friendships with his translators, and his work with Norman Thomas di Giovanni is considered definitive by many English readers. His penultimate work was a travelogue written with his future wife, María Kodama.

This page profiles all of Borges’ collaborations which have been translated and published in English—and a few which have not. For a full bibliography of Borges’s Spanish-language collaborations, consult the Borges Center. The works are listed in chronological order:

Antiguas literaturas germánicas / Ancient Germanic Literatures (1951)

El “Martín Fierro” (1953)

El libro de los seres imginarios / The Book of Imaginary Beings (1957–1969)

Introducción a la literatura inglesa / An Introduction to English Literature (1965)

Literaturas germánicas medievales (1965)

Introducción a la literatura norteamericana / An Introduction to American Literature (1967)

Atlas (1984)

Borges’ many collaborations with Adolfo Bioy Casares are located under Collaborations with Bioy Casares. All book images include the Spanish first edition where appropriate; subsequent English translations are generally represented by their most “current” covers. Clicking the image of a book takes you directly to Amazon.com, unless it’s the original first edition, which just enlarges the image. Wherever possible, links to the Internet Archive are provided. These “online editions” may or may not match the exact edition of the corresponding book.

Antiguas literaturas germánicas

Ancient Germanic Literatures

Antiguas literaturas germánicas

By Jorge Luis Borges & Delia Ingenieros

Mexico: Fonda de Cultura Económica, 1951

Ancient Germanic Literatures

By Jorge Luis Borges & Delia Ingenieros

Translated by M.J. Toswell

ACMRS Press, 2014

The product of Borges’ fascination with Teutonic verse, this book collects essays on Anglo-Saxon, Germanic, Icelandic, and Scandinavian literature. It contains “La poesía de los escaldos” (“The Poetry of the Skalds”), an updated and somewhat tempered version of “Noticia de los kenningar,” an essay with a twenty-year history of revisions from Sur to Las kenningar to Historia de la eternidad. (See Borges Nonfiction for details.)

The title page of Antiguas literaturas germánicas credits Delia Ingenieros as Borges’ co-author. The daughter of Argentine essayist and philosopher José Ingenieros, Delia was a writer and magician who would later pursue a career in biology. She was also the sister of Cecilia Ingenieros, one of Borges’ early unrequited loves. Delia Ingenieros had previously collaborated with Borges on the short story “Odin,” which had been published in the Antología de la literatura fantástica in 1940. The exact nature of her collaboration with Borges on Antiguas literaturas germánicas is unknown; it’s likely she helped organize his research and took dictation as his eyesight failed. (A pattern to be repeated throughout the remainder of Borges’ life.)

English Translation

In 2014 medievalist and Anglo-Saxon scholar M.J. Toswell published the first English translation of Antiguas literaturas germánicas for the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Correcting several of Borges’ inconsistencies and mistranscriptions, Toswell remarks in her introduction that “errors in Borges’ understanding, which are rare, have been left untouched.” (She also concludes with some fond amusement, “The judgments he makes are sometimes quirky, but always justified and intelligent; it is worth reading Borges on medieval Germanic texts.”) The contents of the 2014 English translation are as follows:

Preface and Acknowledgments (M.J. Toswell)

Borges and Medieval Germanic Literature (M.J. Toswell)

Note on the Text (M.J. Toswell)

Prologue

1. Ulfilas

2. The Literature of Anglo-Saxon England

3. Scandinavian Literature

4. German Literature

Appendix 1. The Flight of Walter of Aquitaine

Appendix 2. Ariosto and the Nibelungenlied

Bibliography

In 1965 Borges expanded and revised his survey as Literaturas germánicas medievales, now crediting María Esther Vásquez as his collaborator. (See below.)

El “Martín Fierro”

El “Martín Fierro”

By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero

Buenos Aires: Columba, 1953

Online at: Internet Archive

The early 1950s saw Borges and his circle adopting a fiercely anti-Peronista stance, rejecting the surge of nationalism and xenophobia that followed in the wake of Perón’s constitution of 1949 and his landslide electoral victory in 1951. It was this atmosphere that precipitated Borges’ enduring speech, “The Argentine Writer and Tradition,” delivered to the Colegio Libre de Estudios Superiores in 1951 and later published in Sur and Discusión. It was an exciting time for Borges on a more personal level as well—he had just become romantically involved with a dancer named Margarita “Margo” Guerrero.

Like many of Borges’ female friends and companions, Guerrero assisted the increasingly blind writer by taking dictation. Their first major project together was El “Martín Fierro,” Borges’ critique of the epic poem El gaucho Martín Fierro. Written in the 1870s by the poet José Hernández, Martín Fierro is often called the Argentine Don Quixote, and is considered a foundational work of Argentine literature. As a lifelong admirer of the poem, Borges praises Hernández and gauchesco poetry in general, particular the early payadas written by poets like Hernández who actually lived the “gaucho” lifestyle. His effusive praise is tempered by misgivings about repeating the past—Borges expresses some disdain for lesser poets who merely “impersonated” these forms, and rejects any political agenda that would confine Argentine letters to a rigidly nationalist form of literature. On the other hand, Borges scorns critics who deny the unique Argentine character of the poem, especially those who regard Martín Fierro as a mere extension of Spanish literature.

History has not recorded the extent of Guerrero’s collaboration with Borges on El “Martín Fierro,” but when it was published in 1953, Borges insisted her name be included on the title page. The book has never been published in English translation.

El libro de los seres imginarios

The Book of Imaginary Beings

Manual de zoología fantástica

By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero

Mexico: Fonda de Cultura Económica, 1957

Online at: Internet Archive

El libro de los seres imginarios By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero Illustrations by Silvio Baldessari Buenos Aires: Editorial Kier, 1967 |

El libro de los seres imginarios By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero Buenos Aires: Emecé Editores, 1978 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Book of Imaginary Beings By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero Translation and revisions by Norman Thomas di Giovanni New York: E.P. Dutton, 1969 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Book of Imaginary Beings By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero Translation and revisions by Norman Thomas di Giovanni New York: Avon, 1970 Online at: Internet Archive |

The Book of Imaginary Beings

By Jorge Luis Borges & Margarita Guerrero

Translation by Andrew Hurley. Illustrations by Peter Sís

Viking, 2005

Online at: Internet Archive

In the early 1950s, Borges was romantically involved with a dancer named Margarita “Margo” Guerrero. She was an avid believer in the occult, and the pair often visited esoteric bookstores together. She even convinced Borges to write the script for a supernatural ballet called La imagen perdida. (“The Lost Image,” the script for which has been lost.) Energized by her interest in the bizarre, Borges enrolled Guerrero to assist him in creating a fantastic bestiary. Unfortunately, the atmosphere was not conducive to a peaceful working environment—Guerrero had a tempestuous personality, and Borges occasionally joked he was living under a “reign of terror.” Still, he loved her dearly, and was heartbroken when Margo broke off their relationship. Although Guerrero never gave her reasons, a mutual friend believed she had become tired of Borges’ “literary obsessions.” A few years later, Borges published the bestiary as Manual de zoología fantástica, the work that would eventually become The Book of Imaginary Beings.

Partly inspired by Borges’ childhood visits to the zoo, The Book of Imaginary Beings is a whimsical bestiary of creatures drawn from myth, legend, and fiction, ranging from the “A Boa A Qu,” the spiritual incarnation of a staircase in Rajasthan; to the “Zaratan,” an island-sized leviathan that gobbles up careless mariners. Each creature is presented with a brief history and notes, written with Borges’ usual seamless blend of fact and fiction. Because his “facts” here concern mythical creatures, the sketches are even more ambiguous than usual, and one is never quite sure when Borges is faithfully reporting, freely adapting, or cheerfully inventing. Of course, that’s part of the charm, and Borges’ introduction invites his readers to approach the book with the curiosity, confusion, delight, and terror of a child’s trip to the zoo; to “dip into it from time to time, in much the same way one visits the changing forms revealed by a kaleidoscope.”

Publication History

The kaleidoscope metaphor is perhaps more apt than Borges intended. The Book of Imaginary Beings has a dizzying and fractured history, and exists in numerous incarnations. Furthermore, nobody really knows the extent of Margo Guerrero’s involvement. She certainly took Borges’ dictation, but did she suggest some of the creatures and creatively collaborate? Or was she just playing the role of muse?

To summarize the book’s publication history as concisely as possible, Manual de zoología fantástica was published in Mexico and Buenos Aires in 1957 by Fonda de Cultura Económica. The “Manual of Fantastic Zoology” featured eighty-two entries loosely arranged in alphabetical order, preceded by a prológo signed by “J.L.B.” and “M.G.” and dated “Martínez, January 29, 1954.” A decade later, a revised edition was published by Kier in Buenos Aires. Featuring thirty-four additional entries, the book was retitled El libro de los seres imginarios, given a new preface, and illustrated by Silvio Baldessari.

Silvio Baldessari’s Cheshire Cat

New York publisher E.P. Dutton acquired the English rights, and in 1969 Norman Thomas di Giovanni worked with Borges to produce a “revised, enlarged, and translated” version. (This was di Giovanni’s first Borges translation!) Four new entries were included and several others expanded, and the book was published without illustrations. A new preface was added to embellish the 1957 and 1967 prefaces. A year later the Avon paperback came out, but “Margaritta Guerro” had her name misspelled on the title page. In 1978, Borges’ Argentine publisher Emecé Editores issued a version similar to the 1967 Kier paperback. In order to avoid copyright infringements, Baldessari’s illustrations were omitted, the entries were jumbled around, and none of the English material was included.

The Viking Centennial Edition

When it came time for the Borges Centennial in 1999, Andrew Hurley was naturally selected to produce a new translation. Deciding to honor the most “recent” Emecé version and omit the additional material included in the di Giovanni translation, the book was slated to be released by Viking with illustrations by the incomparable Edward Gorey. Tragically, Gorey’s death in 2000 placed this book in the category of “heartbreaking might-have-beens,” a tantalizing library of the imagination that includes Jodorowski’s Dune and Wagner’s opera about Jesus. With Gorey struck with an axe or devoured by mice, Viking tapped Czech-American illustrator Peter Sís for the task.

Like all of Hurley’s translations, his Book of Imaginary Beings is concise and direct, and is wholly consistent with his excellent work on Collected Fictions. While I lament Hurley’s decision to drop the four “American” entries—even if they might have been di Giovanni’s work instead of Borges’—his welcome “Translator’s Note” offers a lucid and detailed description of the book’s tortuous history. He also includes a useful section of end notes, a valiant attempt to track down and annotate Borges’ original sources.

I wish I could be as positive about Peter Sís’ quirky illustrations. I know some readers consider them charming, but I find them unbearably precious, the work of a children’s illustrator whose “real” audience is sophisticated parents. While nobody could have topped Edward Gorey, I would have preferred modern illustrations with more character, detail, and humor. (Gahan Wilson, Erol Otus, Jason Thompson, or John Kenn Moretnsen come to mind.) I also question the criteria used to select which “imaginary beings” earned artistic embellishment; especially because the book contains only a handful of illustrations. Why depict such well-known creatures as the minotaur and the dragon? Surely the six-legged antelope and the squonk would have been more imaginative choices?

Additional Information

The Wikipedia Page for The Book of Imaginary Beings gives the complete table of contents, with links to Wikipedia entries for each creature. Melanie Nicholson wrote an interesting paper on The Book of Imaginary Beings for The Journal of Modern Literature. Called “Necessary and Unnecessary Monsters,” it’s available at JSTOR.

Introducción a la literatura inglesa

An Introduction to English Literature

Introducción a la literatura inglesa

By Jorge Luis Borges & María Esther Vásquez

Buenos Aires: Editorial Columba, 1965

An Introduction to English Literature

By Jorge Luis Borges & María Esther Vásquez

Edited and translated by L. Clark Keating & Robert O. Evans

University Press of Kentucky, 1974

In 1963 Borges befriended a young woman who worked at the National Library—María Esther Vásquez. The girlfriend of a writer and critic who had personally championed Borges’ work, Vásquez was forced to witness her lover’s suicide when he shot himself over a romantic rival. In March 1964 Borges asked Vásquez to accompany him on a tour of Europe, starting at a writer’s conference in Berlin and passing through Denmark to Paris, England, Scotland, Sweden and Spain. The couple grew close during their travels, and became even closer upon returning to Buenos Aires. It is not known whether there was a romantic relationship—Borges was a few decades older than Vásquez—but most sources agree it was probable, though marriage was out of the question. In any event, like Delia Ingenieros and Margo Guerrero before her, María Esther Vásquez helped Borges with his writing, assisting with research and taking dictation. Their first collaboration was Introducción a la literatura inglesa, a brief “Introduction to English Literature” that traced the development of English letters from Beowulf to modern verse.

In 1974 L. Clark Keating and Robert O. Evans translated the book into English for the University of Kentucky, the same team that translated Borges’ later Introduction to American Literature. (The English translations were done in the reverse order of the Spanish publications.)

Literaturas germánicas medievales

Literaturas germánicas medievales By Jorge Luis Borges & María Esther Vásquez Buenos Aires: Falbo, 1965 |

Literaturas germánicas medievales By Jorge Luis Borges & María Esther Vásquez Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1978 |

In 1963 Borges and his young assistant—and possible lover—María Esther Vásquez toured Germany, Denmark, Britain, Scotland, and Sweden. Upon returning to Buenos Aires, Borges revisited his 1951 book Antiguas literaturas germánicas. The text was rearranged, revised, and expanded with the help of Vásquez. It was also given a new name, published as Literaturas germánicas medievales by Falbo in 1965. (As a dramatic side note, Borges’ mother was reported to have been “furious” to see Vásquez’s name accompanying that of her son. Edwin Williamson recounts the story in Borges: A Life.) In 1978 the text was acquired by Emecé Editores, revised again, and published with illustrations.

In 2014 medievalist and Anglo-Saxon scholar M.J. Toswell translated Antiguas literaturas germánicas into English. In her introduction, she explains her decision to translate the first edition instead of the revised edition as a preference for Borges’ “earliest and deepest reactions, the product of the younger mind in enthusiasm and in first discovery of the material.” She refers to the 1965 revision as “a somewhat more scholarly work” that “offers more extensive analysis, though its base throughout is the first text, sometimes rearranged and with some added paragraphs of information.”

Introducción a la literatura norteamericana

An Introduction to American Literature

Introducción a la literatura norteamericana

By Jorge Luis Borges & Esther Zemborain de Torres

Buenos Aires: Editorial Columba, 1967

Online at: Internet Archive

An Introduction to American Literature

By Jorge Luis Borges & Esther Zemborain de Torres

Edited and translated by L. Clark Keating and Robert O. Evans

1. University Press of Kentucky, 1971

2. New York: Schocken, 1974

Online at: Internet Archive

In 1967 Borges published Introducción a la literatura norteamericana. Originally intended as notes for his students, the slim book contains fourteen brief essays about United States literature loosely organized by theme. Although the collection is ostensibly a collaboration with Esther Zemborain de Torres—a somewhat wealthy woman with whom Borges had a lifelong friendship—Borges’ introduction does not delineate their roles, and it’s difficult to determine the extent of their work together. Indeed, her name only appears on the title page: “JORGE LUIS BORGES (de la Universidad de Buenos Aires) en colaboración con Esther Zemborain de Torres.”

Introducción a la literatura norteamericana was translated into English in 1971 for the University of Kentucky Press, who advertised the anthology as an “outsider’s view” of “the literary achievement of the United States.” While modern readers are more likely to acquire the book specifically because that outsider is Jorge Luis Borges, the book’s “Translator’s and Editor’s Preface” is a work of art in itself, a veritable time-capsule of mid-century academic myopia. It begins with the self-defensive notion that American literature must no longer “defend itself”—really? this written in 1971?—and quickly espouses the typical Boomer disdain for genre fiction, a prejudice that Borges himself does not possess, and so casually destroys in his survey. The editors are “surprised” by Borges’ inclusion of Ellery Queen, refer to Western fiction as “what we sometimes call horse opera,” and measure Ray Bradbury by his success at the cinema. (It’s instructive to recall that Fahrenheit 451 was filmed by François Truffaut; and say what you will about the French, they appreciated such “genre” writers as Poe and Lovecraft long before American academia!)

This pearl-clutching before the Gates of Western Culture finally breaks the string with this amazing sentence, best read aloud in a Transatlantic accent and surrounded by potted ferns: “It is, of course, debatable whether popular literature deserves critical recognition; but from the point of view of the outsider, the non-American, who reads American literature for enjoyment and for what it can tell him about the culture of the United States, the esoteric genres have a rightful place.” Oh, thank you great minds of the University of Kentucky! However, it’s the jacket flap that offers the most amusing observation, written entirely without irony: “Especially to be remarked in this collection are the sections on New England puritanism and transcendentalism—elements of the American experience most foreign perhaps to the Latin sensibility.” Yes, Borges, the epitome of Latin passion and sensuality!

As for the content itself, the best summary was provided by Mary G. Berg, who reviewed the anthology for Modern Fiction Studies in their “Tribute to Borges” issue, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Autumn 1973). She writes:

An Introduction to American Literature is one of many critical studies and students’ outlines written by Borges (in extensive collaboration with others), and, like all of these, it is of great interest to anyone who is curious about Borges in his role as a teacher and reader although even in this limited respect, it provides only a merest fragmentary glimpse. The translators attempt to justify the publication of the book by describing it as an “objective” overview of American literature, insisting that “Borges shows the world how others see us” although they admit that “surely Borges himself would consider it a trifle.” The text is disappointing—a series of sketchy notes overburdened with factual detail (birth, death, and educational data) and only occasionally illuminated by Borges’ eccentric summary judgments—and it totally fails to live up to its translators’ claim that it presents a coherent vision of American literature. However, if an Introduction is read as a collection of Borges’ epigrammatic personal pronouncements about certain books he has enjoyed, the essay assumes a certain charm, and the patchwork of unexpected quotations and arbitrary lucidity (amidst the trivia) adds to what we know of Borges’ view of American literature as it has been so much better expressed in dozens of other essays and introductions he has written. It clearly delights Borges to think of Thoreau not reading newspapers (“superfluous since to read the account of one fire or one crime is to know them all”) or of Longfellow consoling himself during the Civil War by translating Dante’s Divine Comedy (like the narrator of Borges’ “Tlön, Ugbar, Orbis Tertius,” who seeks refuge in Browne’s Urn Burial as totalitarianism takes over the world). Borges feels free to single out Hawthorne’s “Wakefield” and Poe’s “The Philosophy of Composition” for analysis, to dismiss Mark Twain’s humor (his “jokes, reaching us now, seem a little tired”) while comparing Huckleberry Finn, Kim, and Don Segundo Sombra and juxtaposing some of the most diverse writers (again reminiscent of the consideration in “Tlön…” of the Tao Te Ching and the 1001 Nights as works of the same “interesting homme de lettres”).

Publisher’s Description: This book, An Introduction to American Literature, is truly a distinctive volume. In it the internationally known Argentine writer and critic Jorge Luis Borges offers a fresh and personal view of the literature of the United States. He touches not only upon most of the major works and writers but also upon such manifestations of popular culture as the western, the detective story, science fiction, and even the oral poetry of the American Indian. Although Borges writes briefly, even succinctly, his comments are notable for their critical insight. He reveals in almost every sentence a keen understanding of American culture. Especially to be remarked in this collection are the sections on New England puritanism and transcendentalism—elements of the American experience most foreign perhaps to the Latin sensibility. Borges has organized his work on esthetic and personal grounds; he has written on those authors and works that have appealed to him. At the same time the fundamental purpose of the book, he says, “has been to encourage an acquaintance with the literary evolution of the nation which forged the first democratic constitution of modern times.”

What began as a guide to study for his Argentine students becomes for Americans a fresh and many-faceted view of their literature.

An Introduction to American Literature contains fourteen essays:

- Origins

- Franklin, Cooper, & the Historians

- Hawthorne and Poe

- Transcendentalism

- Whitman & Herman Melville

- The West

- Three Poets of the Nineteenth Century

- The Narrators

- The Expatriates

- The Poets

- The Novel

- The Theater

- The Detective Story, Science Fiction, & the Far West

- The Oral Poetry of the Indians

- Appendix: Some Historical Dates

- Notes

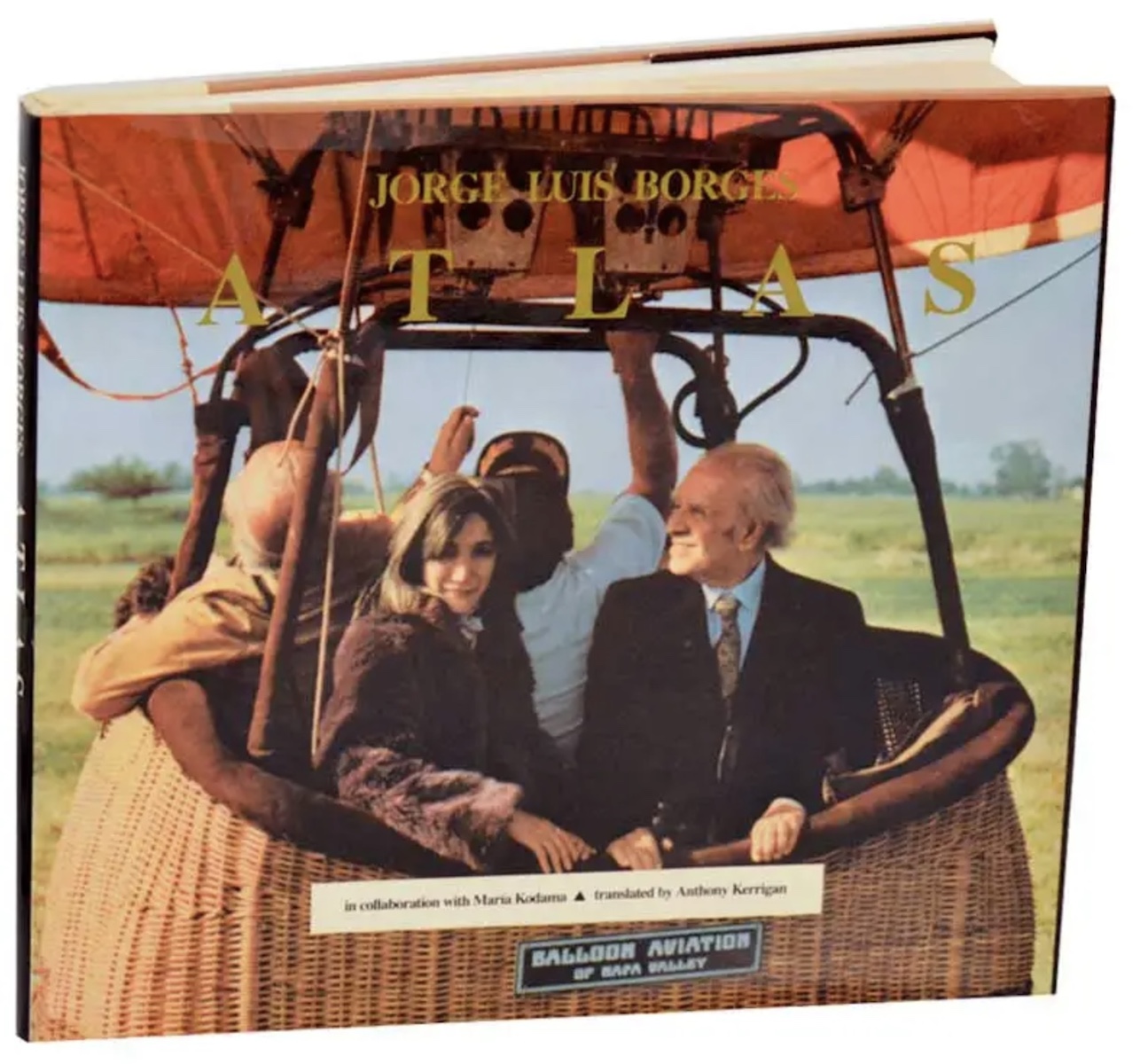

Atlas

Atlas

By Jorge Luis Borges & María Kodama

Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1984

Atlas

By Jorge Luis Borges & María Kodama

Translation by Anthony Kerrigan

New York: E.P. Dutton, 1985

Soon after Borges’ divorce from Elsa Astete Millán, he developed an acquaintance with a student who attended his lectures—María Kodama, an Argentine with Japanese ancestry. She agreed to work as his secretary, and eventually their association blossomed into a collaborative friendship. Throughout the seventies and early eighties, Borges and Kodama traveled the world, trips she documented through her camera, while he recorded his thoughts and impressions. In 1983 the poet Alberto Girri suggested Kodama’s photographs and Borges’ prose could be “interwoven into a prudently chaotic book,” and Enrique Pezzoni, the literary advisor to Penguin’s Editorial Sudamericana and Spanish translator of Moby-Dick, heartily agreed. The end result was Atlas, published in 1984 and immediately translated into English by Anthony Kerrigan.

Presenting their travels as a mythic journey of discovery through time and space, Atlas is the aesthetic and spiritual successor to 1960’s El hacedor (Dreamtigers), and includes dreams, parables, poems, and reflections. Some of these refer directly to accompanying photographs and locations, while others are decidedly disconnected. When Borges’ text and Kodama’s photographs are in close alignment, such as the pages describing their balloon ride in California, Atlas reads like a diary, offering a rare glimpse into the couple’s private life. When word and image are only tenuously linked, the book becomes dreamy and contemplative, the space between the their perceptions revealing the borders between interior and exterior worlds. Often this sense of dislocation approaches the melancholy, and death is frequently on the poet’s mind. Indeed, the strongest piece in Atlas is “A Dream in Germany,” an extension of a theme Borges first expressed in the poem “Límites” from El hacedor. Eliciting wonder and sadness in the same setting, it is worth quoting in full:

Early this morning I dreamed a dream which left me confounded; only later could I put it in some order.

Your forebears engender you.

On the far frontier of the deserts stand dusty classrooms or, if one prefers, dusty storerooms, with parallel rows of worn-out blackboards whose length is measured in leagues, or in leagues of leagues. The precise number of storerooms is not known; doubtless they are many. In each one there are nineteen rows of blackboards and someone has covered them with words and with Arabic numerals written in chalk. The door to each classroom is a sliding door, in the Japanese manner, and made of rusted metal. The writing starts in the left-hand margin of the blackboard and begins with a word. Under it is another and they all follow the strict alphabetic order of encyclopedic dictionaries. The first word is, let us say, Aachen, the name of a city. The second, immediately below it, is Aare, the river of Bern. In third place is Aaron, of the tribe of Levi. Then come abracadabra, and Abraxas. After each one of these words is affixed the precise number of times you will see, hear, remember or use it during the course of your life. The number of times you will pronounce, between the cradle and the grave, the name of Shakespeare or of Kepler, is indefinite, but certainly not infinite. On the last blackboard in a remote classroom is the word Zwitter, German for hermaphrodite, and under it you will use up the number of images of the city of Montevideo which has been assigned to you by destiny, and you will go on living. You will use up the number of times assigned to you to articulate this or that hexameter, and you will go on living. You will use up the number of times your heart has been assigned a heartbeat, and then you will have died.

When this happens the chalk letters and numbers will not immediately be erased. (In each instant of your life someone modifies or erases a figure.) All this serves a purpose we will never understand.

Another standout piece in Atlas is even more personal. Called “My Last Tiger,” Borges begins by enumerating his lifelong fascination with tigers, then describes his experience in a “zoological garden” named Mundo Animal. As the guest of honor, Borges is carefully seated while the zookeeper delivers a living tiger for him to pet. The narrative is certainly charming for any reader familiar with Borges’ fondness for tigers, but its ambiguous title is what really strikes home. It’s possible that “My Last Tiger” acknowledges the flesh-and-blood animal as the capstone and culmination of a lifetime of fictional tigers, painted tigers, and dream tigers. However, one can’t avoid the more obvious meaning. Borges’ awareness of his diminishing years—the erasure of the final chalk tiger from his blackboard—seems more genuine that his reflections on Turkey, which conclude with the witty and hopeful paradox, “Doubtless we should return to Turkey to begin its discovery.”

Atlas reproduces María Kodama’s photographs in black and white, and while they certainly contribute to the book, the majority fall into the category of “Borges looking at something,” or simply depict common monuments and landmarks. Only a few transcend the ordinary vacation photo to capture something essential. The first shows Borges looking up at the Hagia Sophia. Well-framed and expertly composed, the photo is animated by Borges’ unfeigned expression of childlike wonder. The second shows the writer’s hand resting on the inscriptions carved into a Shinto shrine, a subtle but reverent evocation of the accompanying parable—“the visages of divinities are undecipherable kanji.”

The third is inarguably the best photograph in Atlas. Occupying the entire page facing Borges’ remarks on the Cretan Labyrinth, the photograph shows a weary Borges taking a quick rest, leaning on his cane as he seats himself on the crumbling ruin. His hair is tousled, his hands are seamed with age, and his mouth seems open in mid-sentence; or perhaps he’s just catching his breath. It is the one moment in Atlas where the photograph renders the accompanying text superfluous; in this photograph, María Kodama says more about “the labyrinth of time” and “being Borges” than anything else in the book.

Two years later, Jorge Luis Borges and María Kodama were married. On June 14, 1986, at the age of 86, Jorge Luis Borges died of liver cancer in Geneva, a city he commemorated in Atlas by declaring, “I know that I will always return to Geneva, perhaps after the death of my body.”

Borges Works

Main Page — Return to the Borges Works main page and index.

Fictions and Artifices — Short stories; the core Borges works.

Nonfiction — Collections of essays and criticism.

Collaborations with Bioy Casares — Fiction and anthologies written or edited with Adolfo Bioy Casares.

Poetry Compilations — Selections of Borges’ verse translated into English and published as compilations.

Poetry I — Early post-ultraísmo poetry, 1923 to 1943.

Poetry II — Mid-career collections from 1944 to 1969.

Poetry III — Late poetry books from 1969 to 1985.

Lectures, Conversations, and Interviews — Collections of Borges’ lectures, conversations, and interviews.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 14 August 2024

Main Borges Page: The Garden of Forking Paths

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com