Pynchon has written numerous endorsements for his fellow writers, from full-throated recommendations that eventually expand into formal introductions to brief cover “blurbs.” The following collects these endorsements—formal introductions are listed elsewhere on Uncollected Pynchon. The covers selected represent first editions; however, many of these titles are out-of-print, or have changed publishers. For that reason, clicking a cover takes you to the most recent, available, and inexpensive version available on Amazon. In creating this page, Spermatikos Logos would like to acknowledge that we’ve built upon the wonderful work initiated by the

Pomona College site. We are also indebted to the Pynchon Files, Richard Lane’s now-retired Pynchon archive. Additional thanks and credit must be extended to the New York Public Library, and to Amazon.com, whose capsule reviews we borrowed from quite liberally.

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me

Richard Fariña

Original Publishing: Random House, 1966

Pynchon’s old friend from Cornell; he served as Fariña’s Best Man as well as one of his pallbearers. Fariña was also a musician, and is featured

here on the Spermatikos Logos Music Page.

Amazon Synopsis: This is the ultimate novel of college life during the first hallucinatory flowering of what has famously come to be known as The Sixties. Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me follows haunted ur-hippy Gnossos Pappadopoulis upon return to his old university town that’s just tilting into a new era, and Gnossos’ involvement in a swirl of sixties-style drug taking and the search for love and the meaning of it all. It is a hilarious and haunting book.

Pynchon writes: It’s been a while since I’ve read anything quite so groovy, quite such a joy from beginning to end. This book comes on like the Hallelujah Chorus done by 200 kazoo players with perfect pitch, I mean strong, swinging, skillful and reverent—but also with the fine brassy buzz of irreverence in there too. Fariña has going for him an unerring and virtuoso instinct about exactly what, in this bewildering Republic, is serious and what cannot possibly be—and on top of that, the honesty to come out and say it straight. In spinning his yarn he spins the reader as well, dizzily into a microcosm that manages to be hilarious, chilling, sexy, profound, maniacal, beautiful and outrageous all at the same time.

My Escape from the CIA (And Other Improbable Events)

Hughes Rudd

Original Publishing: Dutton, 1966

Unfortunately this book is out of print; but the blurb (thank you NYPL!) suggests that perhaps this work informed some of the thematic material present in Vineland.

Kirkus Reviews: The title story in this collection of thirteen is one of the few “improbable events” that occur and it is no more than a weak playful sketch about a recruit that doesn’t want to be recruited. Mr. Rudd’s two other attempts at humor also seem strained. But where he really succeeds is in the refined cynicism of “Nightwatch at Vernal Equinox” which portrays the synthetic reality of a frowzy Bus Stop restaurant or in the blood and guts agony of his five war stories. He’ll hit you hard with the groping despair of a wounded airman in “The Man on the Trestle,” with the war-madness that overtakes a group of soldiers stationed in Italy in “The Lower Room,” and with the determined callowness of the man stationed in “My House in Heilbronn.” The final piece is non-fiction, a good reportage job of the atmosphere in Oxford, Mississippi after the death of William Faulkner. Ninety-nine and 2/100% purely good.

Pynchon writes: You have a feeling, reading these stories, that Hughes Rudd, like some kind of a satanic Santa Claus, is leading you in under under the shadow of the great, grotesque American Christmas Tree and over to an assortment of gift packages, each one of which is quietly ticking. The explosions may come while you’re reading, or after you’ve finished a particular story. But it’s the thought behind them that really counts: to bring you, ready or not, into the presence of truth. Without copping out behind idle metaphors or irrelevant plot devices, Mr. Rudd has succeeded in telling, with all his reporter’s love of accuracy, and mastery of detail, and irony, and grace, and sometimes terrifying precision, exactly what the hell having to be an American, now, during the years of total war, epidemic anxiety and mass communications whose promise has been corrupted, is really about; where it’s really at. He comes as close to the core of the business as anybody has, because he is not only a writer with an enormous genius for spinning a yarn, but also one whose fine ear is tuned both to the reverberations of global history and to the secret whisperings of the human spirit. It is our good luck as readers to share, and certainly to ponder ourselves, the things he has been listening to.

Looking for Baby Paradise

John Speicher

Original Publishing: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967.

John Speicher was one of the lesser-known Beat writers, a resident of the Village and the author of several excellent books. This novel also features a blurb by Joseph Heller.

Publisher’s Weekly: A strong, disturbing novel, this is, by turns, a horrible, funny, sad and savage picture of human beings who are deprived of practically everything. The central figure is Charlie Kremmel, a social worker in the Washington Heights section of New York City, who is working with every tough kids, among them Hermano Paradiso, “Baby Paradise.”

Pynchon writes: Watch this Speicher cat, he’s a writer of fine and startling talent. His novel is not only funny and frightening, absorbing, compassionate and skillfully-paced, but underneath you can also feel good solid rage, a deep sense of care, and most hopefully a refusal to believe that the world he’s telling about really has to be like it is. For reasons Americans have only lately begun looking into, and in the best sense of the word, “Looking for Baby Paradise” is revolutionary.

DeFord

David Shetzline

Original Publishing: Random House, 1968.

David Shetzline was part of the “Cornell Group” of writers in the late sixties, a group of friends that included Thomas Pynchon, Richard Fariña, and Shetzline’s wife, Mary F. Beal. (Indeed, “Shetzline” is a familiar name for readers of Gravity’s Rainbow!) Dedicated to the memory of Richard Fariña, DeFord is Shetzline’s first novel, and reads like a missing chapter from the lives of Benny Profane and the Whole Sick Crew.

Independent Publisher: In DeFord, a septuagenarian from a long line of losers is passing through New York City when he is felled by a sudden heart attack. Recuperating in a fleabag hotel, he is beset by a deformed Indian named Joe Raven who, having stolen DeFord’s pension check, dogs his footsteps trying to get the old man to sign it over to him. DeFord enlists a drunken painter to help him recover the check. As the painter leads him through the Bowery’s seamy jungle of broken men, DeFord begins to reflect on what may be his first real attachments and last adventure in a long, peripatetic life. DeFord was written in the sixties, and sixties’ spirit and style pervade it. Like Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, … DeFord is filled with baroque characters who have been dropped onto a picaresque landscape. Some of the novel’s situations haven’t aged well, such as the relative ease with which Bowery bums mix with the elite New York art crowd. Characters often seem endlessly self-referential, as well as improbably deep. But the machinations of Joe Raven and his crew to get DeFord’s money are strikingly inventive, while DeFord’s reveries are provocative and often beautiful. DeFord is recommended to readers, who like to immerse themselves in a novel’s characters and are not daunted by an elaborate style.

Pynchon writes: This is an extraordinary book, quickened by honest rage, written with sustained grace; comic; impassioned, and always deeply moving. For at its heart is an awareness that the America which should have been is not the America we ourselves live in; that the dissonances set up between the two grow wider and more tragic. What makes Shetzline’s voice a truly original and important one is the way he uses these interference-patterns to build his novel, combining an amazing talent for seeing and listening with a yarn-spinner’s native gift for picking you up, keeping you in the spell of the action, the chase, not letting go of you till you’ve said, yes, I see; yes, this is how it is.

Nog

Rudolph Wurlitzer

Original Publishing: Random House, 1968

Amazon Synopsis: In Rudolph Wurlitzer’s signature hypnotic and haunting voice, Nog tells the tale of a man adrift in the American West, armed with nothing more than his own three pencil-thin memories and an octopus in a bathysphere.

Pynchon writes: Wow, this is some book, I mean it’s more than a beautiful and heavy trip, it’s also very important in an evolutionary way, showing us directions we could be moving in—hopefully another sign that the Novel of Bullshit is dead and some kind of re-enlightenment is beginning to arrive, to take hold. Rudolph Wurlitzer is really, really good, and I hope he manages to come down again soon, long enough anyhow to guide us on another one like “Nog.”

Dance the Eagle to Sleep

Marge Piercy

Original Publishing: Doubleday, 1970.

Book Description: They call themselves the Indians. Shawn, a magnetic rock star; Corey, part Indian, whose heritage gave the movement its name; Billy, a brilliant young scientist; and Joanna, a pretty runaway “army brat” who survives on pot and sex. Through the experiences of four young revolutionaries, this macabre and moving adventure brings an all-too-possible future into shattering focus. From the author of Women On the Edge of Time.

Pynchon writes: Here is somebody with the guts to go into the deepest core of herself, her time, her history, and risk more than anybody else has so far, just out of love for the truth and a need to tell it. It’s about time.

According to the Pynchon Files, Pynchon also had this to say about the book in a letter to its publisher: “It’s so good I don’t even know how to write a coherent blurb . . . an all-out honest-to-God novel, humanity and love hollering from every sentence and the best set of characters since Moby-Dick or something.”

Ayisha

Helen Noga

Original Publishing: Arbor House, 1972

This book rarely appears on Pynchon Blurb lists, and we have Richard Lane to thank for it. Spermatikos Logos has no idea why Pynchon blurbed the book, or why it’s “bound to cause a stir!” Indeed, we haven’t even confirmed the blurb is true! If any visitor knows better, please don’t burst our Ayisha bubble.

GoodReads: Set in the Middle East in the early part of the twentieth century, this novel portrays the story of a young woman caught in the age-old clash between Armenians and Turks. Ayisha falls in love with Bayazid, who marries her to save her from a barbaric fate.

Pynchon writes: It’s some book and surely bound to cause a stir.

SDS: Ten Years Toward a Revolution

Kirkpatrick Sale

Original Publishing: Random House, 1973

Kirkpatrick Sale, “the first writer ever given access to the SDS archives,” tells the story of the rise and fall of the Students for a Democratic Society.

Pynchon writes: SDS is the first great history of the American prerevolution. . . . It will stand not only on its extraordinary merits because it is a source of clarity, energy and sanity for anyone trying to survive the Nixonian reaction, but also as one book that was there when we needed it the most.

Amazon One

M.F. Beal

Original Publishing: Little, Brown 1975

Mary F. Beal was part of the “Cornell Group” of writers in the late sixties, a group of friends that included Thomas Pynchon, Richard Fariña, and Beal’s husband, David Shetzline. She won the Atlantic Grant for this debut novel, a tale of four radical women and their experiences in a fictionalized Weather Underground. Amazon.com says the novel “exposes the political reasoning, the private sensibilities, the anger and fear of a group of radical activists convinced that America is the enemy and violence their salvation.” Pynchon’s blurb did not actually appear on the book itself, but was used in the NYRB advertisement:

Pynchon writes: I love this book. It is authentic and deeply felt, it moves with grace, speed, and surprise, it makes you feel good and also gets you angry, it takes you into the lives of people you can care about and believe in—especially Kam, who is the most engaging guerrilla to show up in American writing since Hemingway’s Robert Jordan. This is novel-writing the way it should be, all-out, maniacal, professional.

Far Tortuga

Peter Matthiessen

Original Publishing: Random House 1975

Amazon Comments: Far Tortuga tells the story of a handful of superstitious turtle fisherman from Grand Cayman as they begin a voyage late in the hunting season of 1968. Not only do they fight the rising seas, but fight among themselves with results that range from comic to tragic. They encounter rival turtlemen, a frightening white object that hovers just beneath the ocean waves (dead whale?), a mysterious man in a blue boat that speaks not a word, and the desolate island of Far Tortuga. Most of the story is told through the spoken words of the characters, written in Carribean islander dialect that would do Mark Twain proud. However, the printed word is only a part of the story. The simplistic illustrations of Kenneth Miyamoto suggest sunrises, sunsets, night skies, storms and ocean horizons. They compliment the text perfectly and serve as unique dividers between chapters and subchapters. One cannot imagine the book without them.

Pynchon writes: I’ve enjoyed everything I’ve ever read by Matthiessen, and this novel is Matthiessen at his best—a masterfully spun yarn, a little otherworldly, a dreamlike momentum . . . It’s full of music and strong haunting visuals, and like everything of his, it’s also a deep declaration of love for the planet. I wish him and it all kinds of fortune.

Even Cowgirls Get the Blues

Tom Robbins

Original Publishing: Houghton Mifflin 1976

Amazon Synopsis: Starring Sissy Hanshaw—flawlessly beautiful, almost. A small-town girl with big-time dreams and a quirk to match—hitchhiking her way into your heart, your hopes, and your sleeping bags… Featuring Bonanza Jellybean and the smooth-riding cowgirls of Rubber Rose Ranch. Chink, lascivious guru of yams and yang. Julian, Mohawk by birth; asthmatic esthete and husband by disposition. Dr. Robbins, preventive psychiatrist and reality instructor… Follow Sissy’s amazing odyssey from Virginia to chic Manhattan to the Dakota Badlands, where FBI agents, cowgirls, and ecstatic whooping cranes explode in a deliciously drawn-out climax…

Pynchon writes: I did get the advance copy of “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues” but people started borrowing it. “Gee, this is a great book. How come you haven’t read it yet?” Passage of time. Me: “You’re not through with it yet.” “I’m reading it slow. I don’t want it to end.”

When I finally did get hold of it again, I was prepared to hate it. But ended up loving it and reading it slow because I didn’t want it to end. Tom Robbins has a grasp on things that dazzles the brain and he’s a world-class storyteller. This is one of those special novels—a piece of working magic, warm, funny, and sane—that you want to ride off into the sunset with.

I hope the book sells and sells and winds up changing the brainscape of America, which sure could use it.

Thanx, pardners.

The Pagan Blessing

Phyllis Gebauer

Original Publishing: Viking 1979

Amazon Synopsis: When Benito Bazan, a fisherman from a small village in Spain, accidentally discovers two ancient gold statueettes in a cave, his first thought is of a new fishing boat he will now be able to buy. When he examines them more closely, he finds that the figures are of a man and a woman, beautifully fashioned and admirably endowed. Both are smiling. Whe Benito joins them together, he finds their endowmets make a perfect fit. Benito and his wife are the first villagers to gaze upon the lubricious pair, and the effect on them is immediate, overwhelming, and unambiguious. With an ardor and entusiasm neither has felt in years, Benito and his wife make love. Word of the statues and their magical power spreads through the village, and everyone from the mayor down to the local smuggler takes his rolicking part in the action that follows. Here is a comic romp of a novel celebrating the delights and confusion of love.

Pynchon writes: Dear Phyllis. . . Just finished reading “The Pagan Blessing,” and enjoyed it enormously—in fact, loved it. Not just the writing, which is excellent, but also the feeling, the experience, of reading it. I didn’t want your book to end, which usually means I know I’m reading something special. I think you’ve got a lot going here—the locale, which is fascinating and offbeat, characters who are alive and engaging, a clean up-tempo story line, action, color, comedy, romance—you’re right in sync with the “populist” awareness that local is better than centralized, you write about country people without sliding into fake pastoral, and best of all you’ve celebrated here, magically, the simple power of love. In short, it’s a damn good piece of work. Thank you for a delightful, touching, and entertaining journey. ¡Vivan los amantes célticos!

Sounding the Territory

Laurel Goldman

Original Publishing: Knopf, 1982.

Amazon Synopsis: Jay Davidson struggles to cope with the overwhelming chaos and complexities of modern life and to restore himself to sanity following a nervous breakdown.

Pynchon writes: An astonishing piece of work! I wasn’t at all prepared, reading a book full of such laughter and vertigo, to be moved, and touched, as deeply as I was. Laurel Goldman brings to her writing a high-level quality of attention, a demonic sense of humor, a serious respect for life’s darkness—it is writing which is able, in the most surely felt way, to enter a reader’s heart.

Days Between Stations

Steve Erickson

Original Publishing: Simon & Schuster 1985

Synopsis: A fragment of a film, a young woman’s face are the only clues in a man’s search for his past from hallucinatory Los Angeles where the freeways are buried in sand and dust storms obscure the sun to a Paris where the lights have gone out and bonfires burn in the streets. Lives intercut with each other and past joins future in a seamless flow, while the present remains elusive and fleeting. Steve Erickson’s hypnotic, first novel is a dreamscape where imagination and reality collide and merge.

Pynchon writes: Daring, haunting, sensual. . . . Steve Erickson has that rare and luminous gift for reporting back from the nocturnal side of reality, along with an engagingly romantic attitude and the fierce imaginative energy of a born storyteller. It is good news when any of these qualities appear in a writer—to find them all together in a first novelist is reason to break out the champagne and hors-d’oeuvres.

Lion at the Door

David Attoe

Original Publishing: Little, Brown, 1989.

Publisher’s Weekly: In the bleak and impoverished setting of England’s industrial Midlands, first novelist Attoe fleshes out with vivid, visceral immediacy the painful deformation and extinction of the human spirit by trans-generational drunkenness, family violence and incest. There are shades of D.H. Lawrence in Hazel Sapper’s 1940s’ childhood as the daughter of a brutishly abusive miner father. She comforts and renews herself in the powerfully evoked surrounding countryside with Rosko, her bosom friend. Attoe has a wonderful ability to summon up and celebrate the natural world without lapsing into sentimentality. (In one memorable incident, Hazel falls in with a poacher named Pockets, who, to the little girl’s dismay, roasts her a hedgehog in a ball of mud over an open fire.) To survive with his spirit intact, Rosko flees his own abusive home, disappearing into the woods and leaving Hazel desolate and numb. Related initially by Hazel as a child, the novel’s viewpoint shifts to her emotionally stunted daughter in the late ‘70s, further illuminating the tragic dimensions of Hazel’s suffering, and then to Rosko upon his belated return. All the characters’ voices ring true and the narrative evinces the seemingly effortless command one expects of a seasoned writer rather than a promising neophyte.

Pynchon writes: In a quietly passionate voice that speaks to our hearts, David Attoe has brilliantly, honorably imagined himself into lives whose truths we recognize, lives otherwise only lost, and with his eloquent care, rescued them from the silence.

Destiny Express

Howard A. Rodman

Original Publishing: Atheneum, 1990.

Publisher’s Weekly: In the late winter of 1933, German director Fritz Lang prepares to release a new movie. He is troubled by the disintegration of his marriage to screenwriter Thea von Harbou and by ominous Nazi policies that are driving many Jews and leftists to flee. (Lang bumps into Helene and “Bert” Brecht as they entrain for Prague.) Lang pines for Thea (involved with a young American), tries to lose himself in work and fights the studio’s cancellation of his movie’s release. When Goebbels asks him to head “a new program for the cinema,” the director must decide whether he will leave Germany. Scriptwriter and journalist Rodman adapts expressionist film techniques—crosscutting, minute observation, symbolism, the enhancement of mood by the play of light and shadow—to nice effect. Movie buffs will also enjoy the insider references in this quirky but compelling novel.

Pynchon writes: Daringly imagined and darkly romantic—a moral thriller.

Stone Junction: An Alchemical Potboiler

Jim Dodge

Original Publishing: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990

Back Cover: Stone Junction is a wise and wildly imaginative novel about Daniel Pearse, an orphaned child who is taken under the wings of the AMO-Alliance of Magicians and Outlaws. An assortment of sages sharpen Daniel’s wide-eyed outlook until he has the concentration of a card shark Zen master, via apprenticeships in meditation, safecracking, poker, and the art of walking through walls. The AMO know wizards are made, not born, and this unconventional education sets Daniel on the trail of a strange, six-pound diamond sphere, held by the U.S. government in a New Mexico vault, rumored to be the Philosopher’s Stone or the Holy Grail. Shadowing the slippery netherworlds of role-playing games like Magic or Dungeons & Dragons, Daniel’s quest to retrieve the magic stone and discover who killed his mother becomes a bravura act of storytelling, both a free-spirited adventure and a parable about the powers within us all.

Pynchon writes: Here is American storytelling as tall as it is broadly imagined and deeply felt, exuberant with outlaw humor and honest magic. Reading “Stone Junction” is like being at a nonstop party in celebration of everything that matters.

Pynchon penned a lengthy introduction to the second edition, the full text of which may be read

here.

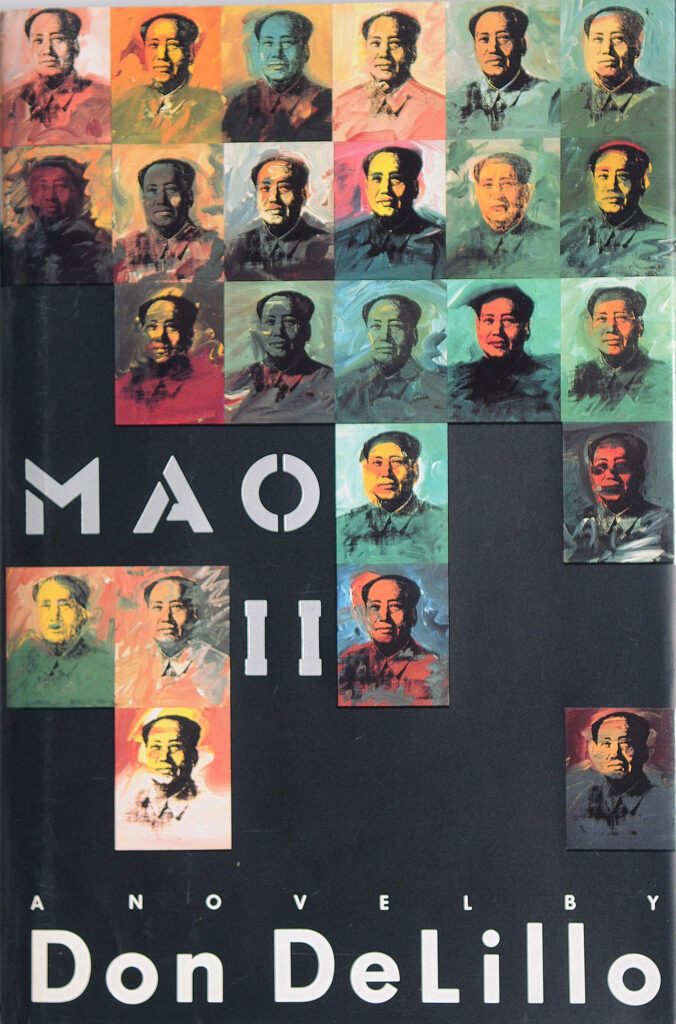

Mao II

Don DeLillo

Original Publishing: Viking, 1991

Amazon Synopsis: Don DeLillo’s follow-up to Libra, his brilliant fictionalization of the Kennedy assassination, Mao II is a series of elusive set-pieces built around the themes of mass psychology, individualism vs. the mob, the power of imagery and the search for meaning in a blasted, post-modern world. Bill Gray, the world’s most famous reclusive novelist, has been working for many years on a stalled masterpiece when he gets the chance to aid a hostage trapped in a basement in war-torn Beirut. Gray sets out on a doomed, quixotic journey, and his disappearance disrupts the cloistered lives of his obsessed assistant and the assistant’s companion, a former Moonie who has also become Bill’s lover. This haunting, masterful novel won the PEN/Faulkner Award in 1992.

Pynchon writes: This novel’s a beauty. DeLillo takes us on a breathtaking journey, beyond the official versions of our daily history, behind all easy assumptions about who we’re supposed to be, with a vision as bold and a voice as eloquent and morally focused as any in American writing.

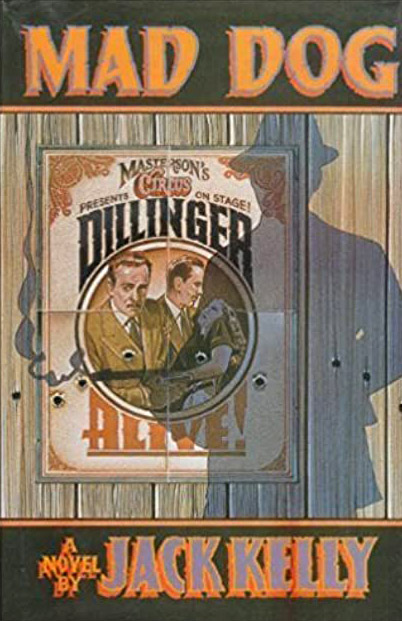

Mad Dog

Jack Kelly

Original Publishing: Atheneum, 1992.

Kirkus Reviews, 1 January 1992: While John Dillinger roams the Midwest robbing banks and breaking hearts, a minor flimflam man takes the Hoosier as his role model and finds professional success—in this melancholy criminal study by the author of Apalachin (1987) and Protection (1989). The nameless co-protagonist of Kelly’s deft study of unsophisticated crime in an unsophisticated place and time is a down-at-the-heels con artist—one who makes his living selling miraculous, vaguely electric “Kaiser Belts” to impotent rubes until he is arrested and nearly lynched after being mistaken for America’s most wanted criminal. The medicine man takes his sketchy resemblance to Dillinger to a one-ring circus and builds a successful sideshow act impersonating the bank robber, portraying his latest crimes, and telling the folks how he feels. The circus and the criminal work the same territory—the underpopulated and underpaid heart of America at the height of the Depression—allowing the impersonator to get closer and closer to his model, eventually even meeting Billie Frechette, Dillinger’s half-Indian mistress. Abandoned by Dillinger shortly before his Main Street execution, Billie herself turns to the performance circuit, parading before the crowds of small-town people who instinctively recognized her boyfriend as one of their own and who can never hear enough about him. Kelly occasionally succumbs to the temptations of poetry and elevated style, but for the most part he is bang-on in this poignant black-and-white sketch of inept crimes, modest criminals, and gray times.

Pynchon writes: Lyrical and fast-driving, this tale of Dillinger’s last days restores to us with brilliant fidelity a long-unredeemed part of our true outlaw heritage.

We’ve Had A Hundred Years of Psychotherapy And The World’s Getting Worse

James Hillman & Michael Ventura

Original Publishing: Harper Collins, 1992.

Amazon Comment: An unflinching critique of modern psychotherapy. In this stream-of-consciousness assay of modern psychotherapy, James Hillman and Michael Ventura pull no punches in their thoughtful and provocative conversations and letters. The interplay of Ventura’s relentless questioning and Hillman’s acerbic and, at times, seemingly heretical replies strip the clothes off the emperor of modern psychotherapy. The synergy created in the authors’ conversations and exchange of letters in worth the price of admission alone. This book is essential reading for those willing to question the value and values of modern psychotherapy and its grip and the psyche of Western culture.

Pynchon writes: This provocative, dangerous, and high-spirited conversation sounds like one that many of us have been holding with ourselves, more and less silently, as times have grown ever darker. Finally somebody has begun to talk out loud about what must change, and what must be left behind, if we are to navigate the perilous turn of this millennium and survive. For bravely lighting up these first beacons in the night, Ventura and Hillman deserve our thanks as well as our closest attention.

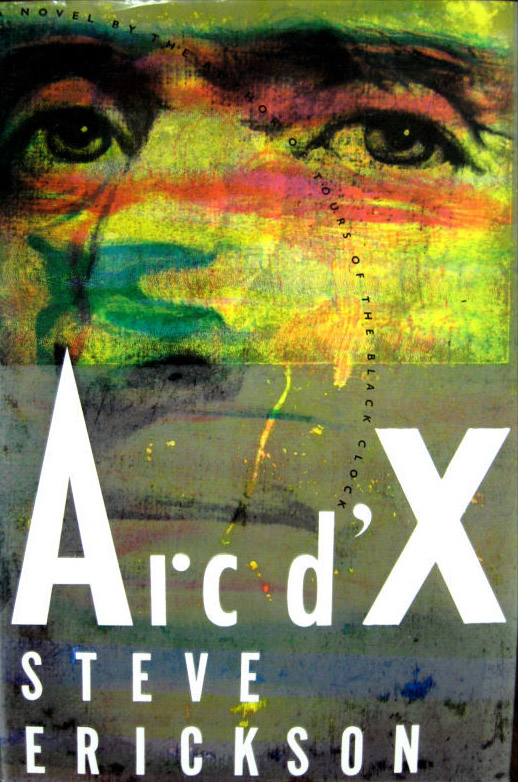

Arc d’X

Steven Erickson

Original Publishing: Poseidon Press, 1993.

Kirkus Reviews, 1 February 1993: A bold and occasionally brilliant interpretation of American history—but marred by a too obvious cerebration that numbs, turning original ideas into mere conceits. Appropriating the rumored liaison between Thomas Jefferson and the slave Sally Hemings, Erickson (Tours of the Black Clock, 1989, etc.) makes that relationship not only a recurring event in the following centuries but uses it as a metaphor for a conflict between the heart and history. For Erickson, this relationship personifies Jefferson’s inability to separate history—the need to further human freedom—from the “pursuit of happiness”—the needs of his heart. This, the novel suggests, is the same conflict that has also shaped America’s destiny. And beginning with Jefferson’s childhood memory of a slave burned at the stake and ending as the millennium threatens cataclysmic disaster, this conflict is repeatedly reenacted and dissected. In settings that include revolutionary Paris; a sinister city-state ruled by the Primacy; and a millennial Berlin abandoned by most of its inhabitants, characters resembling the original lovers repeat their first encounter. There’s a rape that becomes a lasting but flawed love reminding Jefferson of his dereliction of ideals, and Sally of her connivance in her continued enslavement. All encounters, whether in the Fleurs d’X, a bar in the red-light area of the Primacy, or in a deserted Berlin hotel are explorations of the intersection—the arc of x—between “history’s denial of the human heart,” on the one hand, and, “on the other, history’s secret pursuit of the heart’s expression.” Which makes for relentless intellectualizing and even more constrained characters as America and the lovers never quite resolve their destructive contradictions, and the “pursuit of happiness”remains “the most forbidden artifact of all.” Much fine writing and many provocative ideas, but nothing connects—ever—even at the many proffered intersections. Clever but cold.

Pynchon writes: Mind-warping in its vision, absolute in its integrity, Arc d’X is classic Erickson—as daring, crazy, and passionate as any American writing since the Declaration of Independence.

Evolove (Poems)

John Berenzy

Original Publishing: 1993

Again, thanks to Richard Lane for this one. We have no other information about this book of poetry, or how it earned a cursory nod from the Pynch.

Pynchon writes: Got it, Read it, Enjoyed it.

CivilWarLand in Bad Decline

George Saunders

Original Publishing: Riverhead Books, 1996

Joanne Wilkinson from Booklist, 1 January 1996: Saunders presents his unique vision of America in the near future in this debut collection of short stories. In a landscape littered by gutted Wal-Marts and condemned Arbys, Saunders’ astoundingly naive characters encounter high-tech absurdity and savage cruelty. Throughout this collection, the author parades one stunning image after the next: see-through cows, a virtual-reality entrepreneur who off-loads and sells his own memories for $3,000 per decade, a cheesy theme park with a SafeOrgy Room and shrink-wrapped clients. These stories are all of a piece, all stamped with Saunders’ hallucinatory, feverish images, so that there is no clear line of demarcation between his pieces. That seems a small quibble, though, in view of his uncanny ability to take readily recognizable elements from the present and warp them just enough to scare and dazzle his readers. These stories are inventive, hilarious, and terrifying.

Pynchon writes: An astoundingly tuned voice—graceful, dark, authentic, and funny—telling just the kinds of stories we need to get us through these times.

Sewer, Gas & Electric: The Public Works Trilogy

Matt Ruff

Original Publishing: Aspect, 1998

Amazon Comment: The closest fictional relatives of Sewer, Gas & Electric may not be books at all but visionary movies like Brazil and Blade Runner. A comic writer and Information Age social satirist of the first water, Matt Ruff has one of the most fertile imaginations you’ll come across, and the confident chops to string the fruits of this inventive intelligence together. The story is set in a near-future Manhattan of mile-high skyscraper construction projects, eco-terrorism, man-eating mutant sewer-dwelling white sharks and even more dangerous corporations.

Pynchon writes: A post-Millennial spectacular — dizzingly readable!

Dreamland: Travels Inside the Secret World of Roswell and Area 51

Phil Patton

Original Publishing: Villard, 1998

Kirkus Reviews, 1 July 1998: Thomas Pynchon meets Hunter S. Thompson (stylistically) in a novelistic account of the US government’s secret air base known as “Area 51.” Area 51 is a chunk of desert in the southwest the size of Belgium. Beside it lies a nuclear testing site. Both are products of the Cold War, when it was believed air power and nuclear power would combine to keep America safe. Area 51 is a secret place, it exists on no maps. It came into being so aircraft, like the U-2, that could spy on the Soviet Union and China might be tested and perfected. Its so secret that it is in effect a black hole that draws to it the paranoid, conspiracy buffs, the just plain loony. There are the “youfers” who search for, and find, UFOs flying above Area 51; there are the “black-plane watchers” who search for ultra- top-secret aircraft. This is the world Patton (Made in the USA, 1992; Open Road, 1986) takes us into. He travels beyond the physical location of Area 51 to the psychic location of those who must believe that in the sky exists a world we are not meant to know. He travels to Roswell, N.M., the birthplace of UFO conspiracy theories, to conventions of alien abductees, to a bar in the desert called the Little A ‘Le’ Inn, where sky watchers share their stories. Why do they believe what they believe, “see” what they “see”? Patton ponders the Jungian notion that flying saucers are “symbolical rumors.” Or perhaps in a Cold War world that, as he writes, would “routinize Doomsday . . . bureaucratize Armageddon” (and this world is not long gone), it takes mystery and the unexplained to give us a sense of common humanity. Patton allows us to question who is loony and who is not. A fascinating meditation on delusion and desire, this is an American tale.

Pynchon writes: A mind-opening tale of trespass and revelation, of road adventures, of technothriller hardware, of saucer folks, and aerospace outlaws—as well as a daring account of our history through the Cold War and beyond by what we have seen, and often wish we had not seen, in the hazardous dreamscape of the American Sky.

The Restraint of Beasts

Magnus Mills

Original Publishing: Flamingo, 1998

This novel was nominated for the Booker Prize, and comes from an author who shares Pynchon’s UK agent.

Amazon Comment: Good fences may make good neighbors, but in Magnus Mills’s first novel, bad fences make for high tension indeed. An eerie noir fable told in a grim, deadpan voice, The Restraint of Beasts begins as an unnamed English fence builder finds himself promoted to foreman over Tam and Richie, two undermotivated Scots laborers. They’ve just been sent out to fix a high-tension fence when events go horribly awry—and that’s just the beginning. For the rest of the novel, as his charges drink, smoke, loaf, and pound the occasional post, things go wrong over and over again. In a sense, that’s all you can truly rely on in Mills’s fictional world. . . In between placing Kafkaesque obstacles in his narrator’s path, Mills seeds his debut with small, darkly comic touches: Tam’s father, whom we last see erecting a stockade round his house “to stop you from coming home any more”; the sound of Richie’s Black Sabbath tapes “slowly being stretched in an under-powered cassette player”; the caravan’s encroaching squalor; An Early Bath for Thompson, the book that Richie tries without success to read. No doubt about it, The Restraint of Beasts is a strange novel that only grows stranger as it progresses; with luck, it augurs more brilliant, odd work from Mills.

Pynchon writes: A demented, deadpan comic wonder, this rude salute to the dark side of contract employment has the exuberant power of a magic word it might possibly be dangerous (like the title of a certain other Scottish tale) to speak out loud.

Slackjaw

Jim Knipfel

Original Publishing: J.P. Tarcher 1999

Jim Knipfel has chronicled his descent into blindness through his memorable columns in the

New York Press. His Web site is

Slackjaw Online.

Synopsis: A columnist for the New York Press provides the story of a young writer surviving the onslaught of retinitis pigmentosa, a rare genetic disease the final result of which is blindness.

Pynchon writes: Slackjaw is an extraordinary emotional ride through the lives and times of reader and writer alike. It is maniacally aglow with a born storyteller’s gifts of observation, an amiably deranged sense of humor, and a heart too bounced around by his history, and ours, not to have earned Mr. Knipfel, at last, an unsentimental clarity that is generous and deep. What begins as a cautionary tale turns out to be, after all, an exemplary American life. The Park Service ought to be charging admission. Long may he continue to astonish us.

Unedited Blurb (From Slackjaw Online): Thank you for giving me the chance to read Jim Knipfel’s “Slackjaw.” It is an extraordinary emotional ride, through the lives and times of reader and writer alike, maniacally aglow with a born storyteller’s gifts of observation, an amiably deranged sense of humor, and a heart too bounced around by his history, and ours, not to have earned Mr. Knipfel, at last, an unsentimental clarity that is generous and deep. What begins as a cautionary tale turns out to be, after all, an exemplary American life. The Park Service ought to be charging admission. Long may he continue to astonish us.

The Testament of Yves Gundron

Emily Barton

Original Publishing: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2000

The first novel from Brooklyn writer and yoga instructor Emily Barton.

Kirkus Reviews, 1999: A brilliant debut skillfully blends creation myth and folk tale with subtle criticisms of both depersonalized technological advancement and the kind of insularity that breeds and overvalues both tradition and ignorance. Barton’s ingenious tale takes the form of an autobiographical document written by the eponymous Yves, a farmer in the landlocked village of Mandragora, which initially seems by virtue of place and personal names to be located somewhere in eastern Europe during the late Middle Ages. But, we soon learn, the land beyond Mandragora’s neighboring mountains lies across a body of water from Scotland; the period is actually an approximate present time when US Navy aircraft fly nearby; and Mandragorans compose and perform elaborate chants that imitate the structure and content of blues songs. Yves’s “testament” recounts, in a beautifully manipulated voice whose semi-formal cadences have a faintly antique ring, his serendipitous “invention” of the harness, which instantly alters his own and his neighbors’ lives changes quickened when a young American anthropology student, Ruth Blum, arrives, bonds rapidly with Yves’s family, stimulates further “Inventions” (such as the four-wheeled cart and the paving of roads), and falls in love with Yves’s chaste and contemplative brother Mandrik le Chouchou, himself a traveler who, like Marco Polo, had returned home with glorious tales about the prosperous cities of the Orient. The story of how Mandragora (another word for mandrake, the plant reputedly capable of inducing a soporific state) “progresses,” from primitivism through (rudimentary) mechanization to a sobered comprehension of (in Ruth’s words, about her own civilization) “what we’ve strayed from, what we once had and have since lost” is powerfully conveyed through a flexible narrative that’s a pitch-perfect imitation of first-person historical reconstruction, complete with (often very amusing) footnotes and comments from Yves’s “editor.” A commanding and extraordinarily accomplished debut.

Pynchon writes: Blessedly post-ironic, engaging and heartfelt—a story that moves with ease and certainty, deeply respecting the given world even as it shines with the integrity of a dream.

A confraria dos espadas

Rubem Fonseca

Original Publishing: 1998

According to the Pynchon Files, this Brazilian collection of short stories earned a blurb from the Man. The Portuguese title may be translated as The Brotherhood of Swords.

Translated from the Portuguese from Amazon: There is no escapist relief in the literature of Rubem Fonseca, and A confraria dos espadas is no exception. All the tales have characters who, in one way or another, go after her “little death,” an expression of French origin that designates orgasm. And, even when no one dies, we come to the end with the impression of having witnessed some variant of the act of dying. Pleasure and death are the theme of the eight stories gathered in the book: they guide the hedonism present in each attitude of the characters.

Pynchon writes: Cada livro dele não é só uma viagem que vale a pena: é uma viagem de algum modo necessária. (“His every book isn’t merely a worthwhile trip; in some ways, it’s a necessary trip.”)

The Verificationist

Donald Antrim

Original Publishing: Knopf, 2000

Kirkus Reviews: Antrim’s novels are so hilariously inventive, so audacious, and so full of a unique blend of ideas and pratfalls that it’s hard to find another contemporary writer to compare him to: Pynchon on lithium? Barthelme on laughing gas? Tom, a psychoanalyst from the prestigious Krakower Institute, decides to gather his other teaching colleagues together for a series of informal suppers to share experiences, gossip, and of course new ideas about “the seemingly endless task of reconciling classical metapsychology to our particular branch of Self/Other Friction Theory.” And what less threatening and more informal venue could he choose than the “Pancake House & Bar?” Among Tom’s colleagues are Manuel Escobar, a suave “Kleinian” therapist who may be suffering from ethical vagueness; the bumptious, uncouth Richard Bernhardt, a group counselor and Tom’s enemy; and the warmly supportive Maria. Matters turn strange when Tom, in an attempt to lighten everyone’s mood, decides to instigate a food fight with a nearby table of prissy child psychologists. The disapproving Bernhardt locks him in a bear hugand somehow thrusts him into an out-of-body experience. For the rest of the night a part of Tom’s consciousness hovers near the ceiling of the pancake house, watching and commenting on the increasingly acrimonious and libidinous pursuits below. The conversations of Tom’s colleagues are rendered in a pitch-perfect parody of psychoanalytic groupspeak, while contrasting nicely with the heated debates over theory and practice are all-too-fleshly appetites and resentments. As matters deteriorate, the situation becomes more and more absurdly hilarious; no one writes better slapstick than Antrim. Tom’s fate is both inevitable and moving. A hilarious send-up of psychoanalysis and a deeply original meditation on the nature of identity. Antrims distinctive, high-octane comedy of ideas may prove dizzying for some. Those who persevere will find themselves, like Tom, seeing matters in a distinctly new way.

Pynchon writes: Donald Antrim is in top form with this high-spirited hallucination, whose characters, undeniably ourselves, carry on engagingly and shamelessly, in an off-the-wall, not to mention off-the-ceiling, environment that is also the world we know, and sometimes wish we didn’t.

The Black Veil: A Memoir with Digressions

Rick Moody

Original Publishing: Little Brown & Company, 2002

Joanne Wilkinson from Booklist: Anyone who has read Moody’s fine fiction (Purple America, 1997; Demonology, 2001) will recognize the voice here: painfully funny, heavily italicized, frequently obsessional, frequently riveting. His memoir covers the years of his early adulthood, when he was often depressed and regularly medicated himself with large amounts of alcohol and drugs. He eventually ended up in a psychiatric hospital, which helped him regain his footing. Convinced that his tendency toward melancholy is a family tradition, Moody researches his lineage, finding a kindred soul in Handkerchief Moody, on whom Hawthorne based his short story “The Minister’s Black Veil” (all of Moody’s chapter titles are taken from this story). This is no ordinary memoir because it seeks to meld the personal and the historical, not always successfully. You would be hard pressed to find a more accurate, more eloquent account of the first, hesitant attempts to find one’s place in the world, which are often accompanied by confusion and loneliness. But Moody’s obsession with his genealogy and the metaphoric implications of a veil (he even attempts to make and wear one that covers his face) is less compelling. He warns readers right up front: “Obsession has its blind spots, it is occasionally inexplicable, it is worrisome, it is amazing and sometimes charming” So is he.

Pynchon writes: Rick Moody, writing with boldness, humor, generosity of spirit, and a welcome sense of wrath, takes the art of the memoir an important step into its future.

The Buzzing

Jim Knipfel

Original Publishing: Vintage Books 2003

Publisher Synopsis: Meet Roscoe Baragon—crack reporter at a major (well, maybe not that major) metropolitan newspaper. Baragon covers what is affectionately called the Kook Beat—where the loonies call and tell him in meticulously deranged detail what it’s like to live in their bizarre and lonely world. Lately Baragon’s been writing stories about voodoo curses and alien abductions; about fungus-riddled satellites falling to earth and thefts of plumbing fixtures from SRO hotels by strange aquatic-looking creatures. Not exactly New York Times material. Maybe it’s the radioactive corpse that puts him over the edge. Or maybe it’s the guy who claims to have been kidnapped by the state of Alaska! But Baragon is now convinced that a vast conspiracy is under way that could take the whole city down–something so deeply strange that it could be straight out of one of the old Japanese monster movies that he watches every night before he goes to sleep. But stuff like this only happens in the movies. Right?

Pynchon writes: The Balzac of the bin is at it again. With this paranoid Valentine to New York—and to a certain saurian colossus noted for his own ambivalent feelings about large cities—Mr. Knipfel now brings to fiction the welcome gifts which distinguished his previous books—the authenticity, the narrative exuberance, the integrity of his cheerfully undeluded American voice.

0

0