Deadwood Stage

- At July 04, 2019

- By Great Quail

- In Deadlands

0

0

Oh, the Deadwood stage is a-rolling on over the plains

With the curtains flappin’ and the driver a-snappin’ the reins

A beautiful sky, a wonderful day

Whip-crack-away, whip-crack-away, whip-crack-away!

—“Deadwood Stage,” from Calamity Jane

Overview

Commonly known as the “Deadwood Stage,” the Cheyenne and Black Hills Company Stage and Express connects Cheyenne to Custer City and Deadwood. Operating from 1876 unto the railroad put it out of business in 1887, the Deadwood Stage was one of the most popular and important stage lines of the Wild West—and one of the most frequently robbed! Although this document focuses on the Deadwood Stage, the information may be easily adapted to any western stage line, which used similar coaches and operated along the same basic principles.

History

In 1874, General Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory. Unfortunately for the whites, the Treaty of Fort Laramie acknowledged the Black Hills as part of Sioux territory. This didn’t stop thousands of prospectors and opportunists from flooding the region, and despite initial attempts by President Grant and General Crook to remove them, it was clear the washíchus were not going to honor the treaty established after Red Cloud’s War. The United States attempted to purchase the lands legally, but many Sioux leaders, particularly Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, refused to sell. As tensions mounted towards war, thousands of people continued to settle the Hills, establishing mining camps that evolved into towns such as Custer City and Deadwood. These settlers required equipment and supplies, so three cities emerged as “jumping off points” to the Black Hills—Sioux City, Iowa; Sidney, Nebraska; and Cheyenne, Wyoming. Whichever city could best supply miners and ensure safe travel to the Black Hills was likely to win dominance, and would certainly prosper as gold fever spread across the nation.

Cheyenne

By late 1875, Cheyenne was emerging as the frontrunner. This achievement was not simply a matter of geographical fate. The city’s politicians and businessmen had been vigorously lobbying to attract more “Hillers” into the city. Not only was the “Magic City on the Plains” conveniently located along the Union Pacific Railroad, it was already in possession of a coach line delivering mail to the northern Indian agencies. Owned by a trader named Frank Yates, the line started in Cheyenne and passed through Fort Laramie on its way north to Spotted Tail and Red Cloud. In early 1876, Yates extended service to Custer City, and the “Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage, Mail and Express Line” was born. It proved to be more difficult than Yates had anticipated, and the first successful coach took nearly a week to make the trip.

Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage Company

Fortunately for Yates, rescue was at hand. Just as he realized he might be in too deep, an agent from Gilmer, Salisbury and Patrick arrived in Cheyenne to scout for possible acquisitions. One of the largest stage operators in the West, GS&P had its origins in two earlier transportation titans—Russell, Majors and Waddell, the founders of the Pony Express; and Wells Fargo, the company that maintained the famous Overland Express. On February 12, their agent E.H. “Stuttering” Brown purchased the Cheyenne Black Hills Stage, Mail and Express Line from Yates & Company. Investing over $100,000 into the project, Gilmer, Salisbury and Patrick announced the formation of the “Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage Company.” Brown immediately announced that the new line would take a shorter route to Custer City, bypassing the Indian agencies and connecting Fort Laramie directly with Hat Creek Station. With Brown heading north to organize the details, noted frontiersman Luke Voorhees was dispatched to Cheyenne to serve as General Manager. Famous for discovering gold on the Kootenai River, Voorhees was an industrious pioneer who understood the harsh realities of unforgiving terrain. Setting up office on Ferguson Street, Voorhees worked tirelessly to establish the most efficient routes, develop stations, and purchase the necessary equipment and livestock.

That the stage line was in direct violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty was of little consequence to its owners or future patrons. The majority of whites believed that the Indians had effectively negated the treaty by their recent attacks on rail-workers, pioneers, and soldiers. All that remained was to receive the official blessing of the Federal government, and the Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express would become a reality. As Federal negotiations with the Sioux continued to falter, Wyoming’s territorial governor John Thayer took matters into his own hand. On April 3, 1876, the first Concord coach rattled out of Cheyenne for the Black Hills. Cheyenne could now boast complete service to the Black Hills—arrive by train, stay overnight at one of the Magic City’s fine hotels, and depart in the morning for Custer City. A few months after launching, the route was extended to Deadwood, and the Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express acquired its lasting nickname, the “Deadwood Stage.”

Illustration from Harper’s Weekly

The Route

The Deadwood Stage runs daily, taking between sixty to seventy hours to deliver passengers from Cheyenne’s Inter-Ocean Hotel to Custer City’s Occidental Hotel. From there, it travels another fifty miles to Deadwood, a trip that takes another six to eight hours. The overall route is divided into halves, with the Southern Division passing through the ranches of the Chugwater Valley between Cheyenne and Fort Laramie, and the more perilous Northern Division snaking through the arid buttes and canyons separating Fort Laramie from the Black Hills. Horses are exchanged every ten to fifteen miles at swing stations, with drivers traded out every forty to sixty miles. Obviously, poor weather may slow things down, but the Deadwood Stage has a reputation for skilled drivers and healthy horses, and the coach usually arrives on schedule.

Return Trips

On return trips, gold intended for deposit in Cheyenne or Denver City banks is stored in secured “treasure boxes” located under the passenger seats. More than a few road agents have made themselves rich robbing stagecoaches and dynamiting the lockboxes, so such trips are often accompanied by a “shotgun messenger”—usually a hired gun sharing the driver’s box or strapped to the rear boot. More on this later!

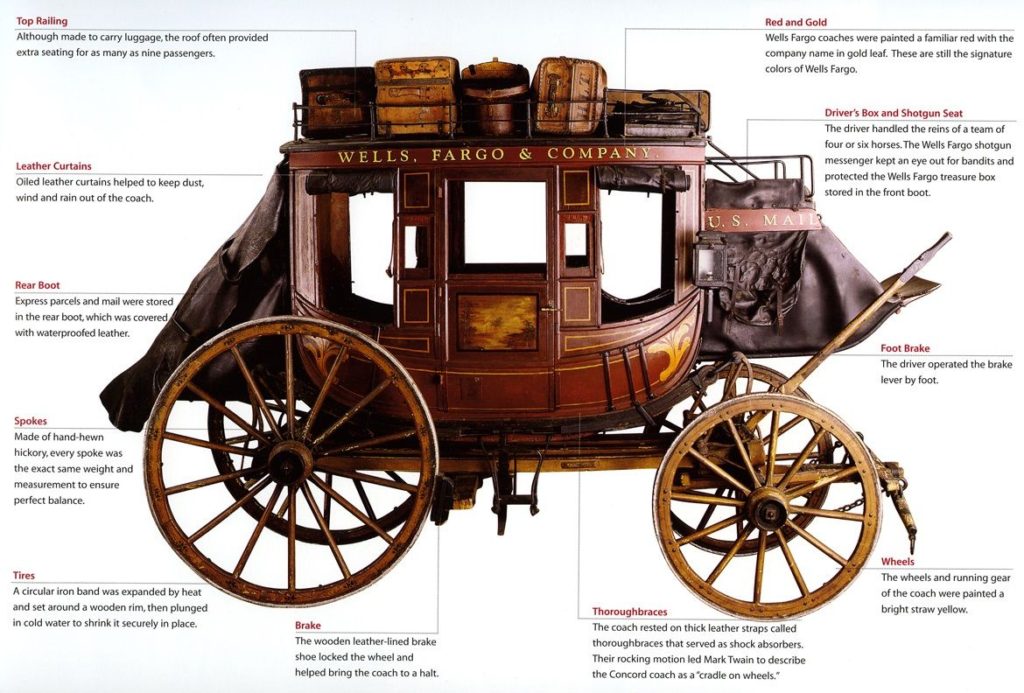

The Concord Coach

The stagecoaches made famous by the West are actually manufactured by the Abbot & Downing Company of New Hampshire, and are called “Concord” coaches after the city of their origin. Made from white oak and ash, and cradled by cured leather thoroughbraces, they are a fusion of artistry and craftsmanship, each coach hand-crafted by a team of 150 employees. The interior of a Concord coach sports plush upholstery stitched by Mary Putnam and features metal scrollwork wrought by Charles Knowlton. Its doors are graced by ornamental panels, each a unique landscape painted by the English artist John Burgum. Concord coaches are painted deep red, which better hides the dust, and given straw-yellow undercarriages. They come in three sizes, intended to hold six, nine, or twelve passengers. Each coach is christened with its own name.

Nine-person Concord coach used by Wells Fargo

The most noteworthy innovation of a Concord coach is its suspension system, a pair of thoroughbraces that replace the springs used by inferior designs. Requiring the hide from a dozen oxen, each thoroughbrace is a three-inch wide, 300-foot long strap of leather looped around itself dozens of times. The twin thoroughbraces cradle the coach, allowing it to sway with shifts in momentum and position. Providing a smoother ride than springs, the thoroughbraces absorb the accustomed shocks of travel, and are superior for the horses as well.

Passengers

The standard interior of a Concord coach is fitted with three cushioned seats, and can pack in nine passengers. Two additional passengers may sit with the driver in his “box,” and the top “dickey seat” has room for four more “hangers-on.” A rear “jump seat” may also be fitted to accommodate four additional riders. Because Chinese passengers were forced to use this notoriously dusty and uncomfortable seat, it is sometimes referred to as the “China seat.”

Concord coaches usually feature two leather compartments called “boots,” one located beneath the driver’s box and one suspended from the rear. Triangular in shape, these compartments are designed to hold mail bags, express packages, cargo, and passenger luggage. When coaches retain “shotgun messengers,” they may ride strapped to the rear boot for the purpose of concealment. On the Deadwood Stage, the driver’s box is sometimes called the “driver’s boot.”

Teams

Many stagecoaches are pulled by a four-horse “hitch,” but a six-horse team is used when extra power is needed. Horses are matched in pairs by temperament, size, and sometimes color. The forward “leaders” are usually the smallest pair, and are trusted to guide the coach and remain alert for danger. The “wheelers” closest to the driver are the largest, and are tasked with steering the coach. In a six-horse hitch, a medium-sized “swing team” in the middle helps shoulder the burden of pulling the coach. Each horse is harnessed with a complex leather “rig” wrapping around its breast, girth, and loins, and sporting two sets of leather straps. The reins, commonly called “ribbons” or “lines,” are used by the driver to control the team, while the “traces” are side straps which connect the horses to the coach itself. The traces are chained to a series of cross-bars called “singletrees,” fixed to a long “whippletree” extending from the forward tongue of the coach. A team’s rig is kept simple and non-ornamental. A long foot-break extending from the carriage allows the driver to slow the coach and avoid obstacles like prairie dog holes.

Wells Fargo Concord coach with a six-horse team

The Driver

Colloquially known as a “jehu,” or sometimes “Brother Whip” or just “Charlie,” a stagecoach driver is the captain of his overland vessel. He is a lonely and romantic figure, generally muscular and quick-witted, necessarily good-humored, and accustomed to ice in his beard or sunburn on his face. The Deadwood Stage employs only veteran drivers, and tasks their drivers to follow a strict code of conduct. A driver must be an excellent horseman, is not allowed to drink or use foul language, and is forbidden to enter the coach during inclement weather. Naturally, they may not sleep on duty, but experienced jehus know how to take light catnaps on easy stretches. A driver controls his team using a whip, usually a five-foot length of hickory sprouting an eighteen-foot lash. A good jehu never whips his horses, but uses the sound of the whipcrack to control his team. He must be a “knight of the ribbons,” coaxing the maximum amount of power from his team while producing the minimum amount of stress. Horses must be kept sleek and “filled out,” and free from injury or sickness. An incompetent driver who lashes his horses, neglects their feeding and grooming, or exhausts his team during a run is soon replaced.

Travel

First class “express” tickets from Cheyenne to Deadwood are $20, the equivalent of $450 today. Second ($15) and Third Class ($10) tickets are available, but these extend the time by two days per downgrade. These inferior tickets may require passengers to ride “mud wagons,” less-comfortable conveyances such as mail coaches or even freight wagons.

Travel Conditions

Despite the modern amenities afforded by the Concord coach itself, any extended ride in a stagecoach is dirty, dusty, and unconformable. No matter the class of ticket held by a passenger, they are expected to get out and walk when conditions require. Coaches may be lightened to better pass flooded areas, or may be floated across swollen rivers. Heavy “drags” may be fixed to the rear to help descend steep inclines. Passengers are expected to assist with breakdowns and delays, and every veteran passenger has stories of being recruited to push a coach from the mud, being denied the comfort of riding with the driver, or being forced to wait outside the coach for hours during a repair. Coaches become hot and stuffy in warm weather, and transform into iceboxes in winter. In colder climes, a stagecoach may be stocked with buffalo robes, and heated bricks wrapped in gunny sacks are used as foot-warmers. Most express routes travel through the night, and sleep is often an impossibility. According to an account published in 1867 by Silas Seymour, Incidents of a Trip Through the Great Platte Valley, to the Rocky Mountains, and Laramie Plains:

Your friends on the front seat get their legs tangled and twisted up with yours, or you get yours twisted and tangled up with theirs—you don’t exactly know which; and, in short, everybody wakes up chaotic and confused, not to say dismal and cross. Of course you try it again after a while you wrap your robes still better about you, you adjust your legs more carefully than before, and settling down again into your corner, think now you will surely get a good sleep. However, you hardly get to nodding fairly, before there comes a repetition of your former dismal experiences, and so the night wears on like a hideous dream. A series of unusual jolts and bumps disgusts every one with even the attempt to sleep, and presently all hands drift into a general talk or smoke. The history of one night is the wretched history of all—only such successive one, as you advance, becomes “a little more so.” Long before reaching Fort Bridger, we were in a sort of half-comatose condition, with every bone aching, and every inch of flesh sore, and with the romance of stage-coaching gone from us forever. Now, if a man’s body were made of india-rubber, or his arms and legs were telescopic, so as to lengthen out and shorten up, perhaps such continuous travelling would not be so bad. But, as it is, I confess, it was a great weariness of the flesh, and looking back on it now, with the Pacific Railroad completed—its express trains and palace-cars in motion—I don’t really see how poor human nature managed to endure it.

Another wonderful description of a stagecoach ride comes from Mark Twain in his 1872 travelogue, Roughing It:

Our coach was a swinging and swaying cage of the most sumptuous description—an imposing cradle on wheels. It was drawn by six handsome horses…We sat on the back seat, inside. About all the rest of the coach was full of mail bags—for we had three days’ delayed mail with us. Almost touching our knees, a perpendicular wall of mail matter rose up to the roof. There was a great pile of it strapped on top of the stage, and both the fore and hind boots were full. We had twenty-seven hundred pounds of it aboard, the driver said—‘a little for Brigham, and Carson, and ‘Frisco, but the heft of it for the Injuns, which is powerful troublesome ‘thout they get plenty truck to read.’ But as he just then got up a fearful convulsion of his countenance which was suggestive of a wink being swallowed by an earthquake, we guessed that his remark was intended to be facetious, and to mean that we would unload the most of our mail matter somewhere on the Plains and leave it to the Indians, or whosoever wanted it.

Whenever the stage stopped to change horses, we would wake up, and try to recollect where we were—and succeed—and in a minute or two the stage would be off again, and we likewise. We began to get into country, now, threaded here and there with little streams. These had high, steep banks on each side, and every time we flew down one bank and scrambled up the other, our party inside got mixed somewhat. First we would all lie down in a pile at the forward end of the stage, nearly in a sitting posture, and in a second we would shoot to the other end and stand on our heads. And we would sprawl and kick, too, and ward off ends and corners of mail-bags that came lumbering over us and about us; and as the dust rose from the tumult, we would all sneeze in chorus, and the majority of us would grumble, and probably say some hasty thing, like: ‘Take your elbow out of my ribs! Can’t you quit crowding?’

Road Agents

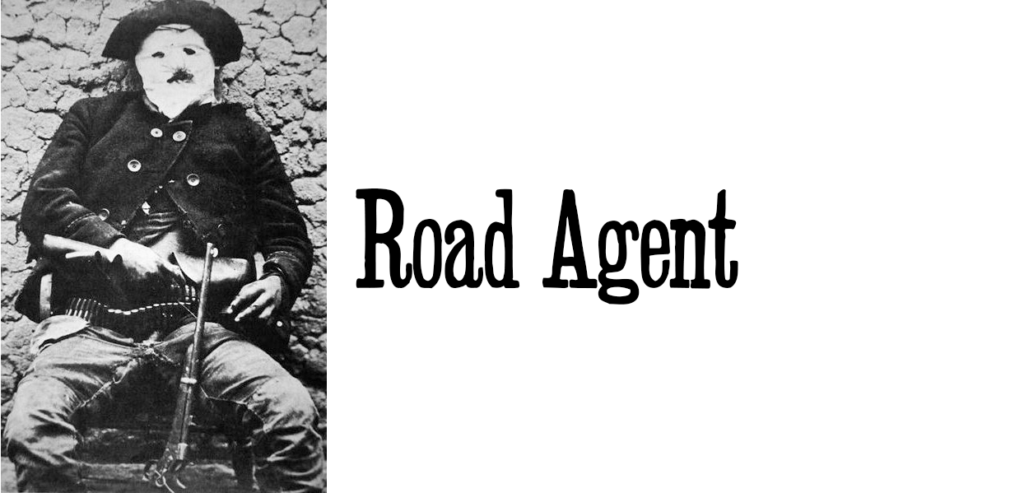

Foul weather, bad roads, and sleepless nights are not the only misfortunes that plague stagecoach passengers. Robbers and highwaymen known as “road agents” are also a risk, particularly on the Deadwood Stage, which is known for its lucrative shipments of gold and currency. Customarily operating in gangs, road agents work along remote stretches of road where they can find easy concealment. Their modus operandi is to stop the coach and order the passengers to disembark. Hands are placed in the air, valuables are surrendered, and cargo is thoroughly searched. If the coach is carrying mail, that is rifled for valuables as well. If the coach features a lockbox, the chest is jimmied or simply unbolted and retrieved wholesale for later opening. Obstreperous passengers and drivers are sometimes tied to the coach wheels.

Road agents frequently wear masks or hoods, but many infamous outlaws are known by name, and have developed perverse relationships with certain drivers—“Well, hello Bill! You know the drill—hands up. Sorry it has to be your coach again, pardner!” Many road agents are allied with insiders as well, informants who advise them on which coaches are safe to rob, which carry armed escorts, and which may be traps prepared by clever detectives. Such insiders may be disgruntled employees or crooked lawmen, but are more often prostitutes, barkeeps, and gamblers who keep their ears open and expect a kickback. Belle Siddons, the “Queen of Deadwood” was one such woman, a faro dealer who directed her lover’s gang to rob passengers she knew were carrying large sums of money or precious valuables.

Recreation of a stagecoach robbery, 1911

Despite what’s depicted in the movies (or the staged photograph above), most stagecoach robberies are carried off with little violence. Road agents realize that committing murder—especially shooting a beloved driver or a well-connected VIP—brings down a significant amount of heat, often triggering an extensive manhunt and perhaps getting the U.S. Army involved. The majority of road agents are cagey and risk-averse, and generally target coaches lacking an armed escort. Still, if a coach is known to contain valuable cargo, it may be worth a gunfight and a few months on the lam!

Security

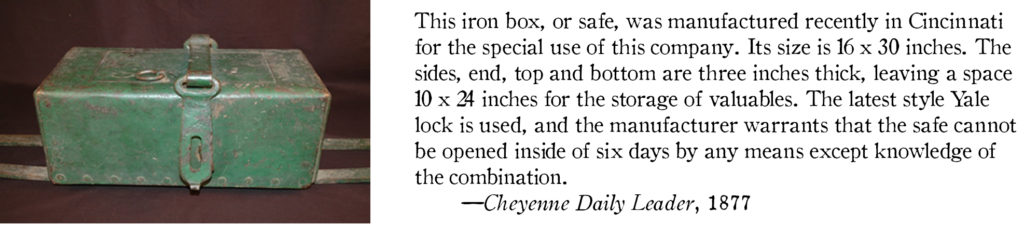

The traditional method of securing valuables during transport was to place them in a “treasure box”—a locked, wooden chest bolted to the coach’s floor. These were hardly an obstacle for dedicated road agents, who simply picked the lock or used dynamite to blow open the box. In 1877, the Cheyenne & Black Hills Company commissioned a treasure box especially designed to thwart road agents. Manufactured in Cincinnati, the chest was lined with thick steel and secured with a Yale lock guaranteed to befuddle thieves for “six days.” Bearing a coat of green paint, it quickly earned the nickname “the salamander.”

Unfortunately, the salamander didn’t perform as advertised, and even Luke Voorhees managed to break the lock within a few hours! Nevertheless, it remains better than a wooden chest, and while it won’t stop the most dedicated road agents, it provides a deterrence factor for casual thieves and offers some peace of mind for bankers.

The Monitor

As the Black Hills became more lucrative, the amount of gold, specie, and valuable paperwork being shipped back and forth between Deadwood and Cheyenne reached record levels. These “treasure coaches” necessitated an increase in security, and armed “specials” and “outriders” were added, some to scout the upcoming terrain, and some to escort the coach itself. The road agents responded in kind, and gangs grew larger, meaner, and more violent—real money was at stake, not just a handful of coins and pocket watches! In response, the Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage Company sought to bolster the physical integrity of the treasure coaches themselves.

In May 1878, the first Monitor coach went into service. Dubbed “Old Ironsides,” it was designed and constructed by A.D. Butler of Cheyenne at the cost of $31,000. The Monitor was fortified with quarter-inch steel plates, featured a salamander bolted to its floor, and had room for two shotgun messengers who took aim through a pair of portholes. A few months later a second Monitor rolled out of Butler’s shop, this one christened “Johnny Slaughter” after the popular driver slain by road agent Robert McKimie.

Canyon Springs Robbery

Old Ironsides was the target of the Deadwood Stage’s most outrageous crime, the Canyon Springs Robbery. On September 26, 1878, an unknown gang ambushed the Monitor, greeting it with a hail of gunfire as it pulled into Canyon Springs Station thirty-seven miles south of Deadwood. The driver Gale Barnett and two shotgun messengers, Gale Hill and Eugene Smith, were wounded; and a telegraph operator named Hugh Campbell was shot dead. The road agents made off with the salamander, which contained $27,000 in gold bullion, diamonds, and jewelry.

The bloody crime launched one of the biggest manhunts in Deadwood history. Sheriff John Manning, Seth Bullock, and Daniel Boone May were involved, and dozens of road agents, horse thieves, and former stage employees were rousted, many of whom claimed no involvement. Thomas Jefferson “Duck” Goodale eventually proved to be one of the ringleaders, but he made a daring escape from a moving train while being transported to custody. Former Quantrill raider Archie McLaughlin was also involved, and when apprehended by vigilantes, he implicated his lover, Belle Siddons. McLaughlin was hanged regardless of his confession, and the “Queen of Deadwood” made a suicide attempt with morphine. The uncompromising response of the legal authorities might have been draconian, but it was effective—the Deadwood Stage was never victimized by another major robbery.

Final Days

In 1883, Buffalo Bill Cody launched “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World,” a grand spectacle he toured across the United States and Europe. One of the show’s highlights was the “Rescue of the Deadwood Stage,” a fictionalized re-enactment of an Indian attack on a stagecoach thwarted by a posse of heroic cowboys. Cody purchased one of Luke Voorhees’ Concords for $1800. Named the Wyoming, the coach was supposedly once ridden by Buffalo Bill himself, and was actually attacked by the Sioux a few years prior. He hired former Deadwood Stage driver Tom Duffy to handle the ribbons, while his Indian performers carried out the daring attack.

One of the most famous anecdotes involving the reenactment comes from Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Celebration in 1886, where Buffalo Bill produced his Wild West spectacular in front of the assembled royalty of Europe. Cody was asked by the Prince of Wales if he and his friends could ride in the coach during the “attack,” and the impresario agreed. The Prince’s “friends” were in fact four kings, the rulers of Belgium, Denmark, Saxony and Greece. After the thrilling sequence had concluded, the future King of England made a poker-related joke—“Colonel, you’ve never held four kings like these!” Buffalo Bill effortlessly responded, “Sure I’ve held four kings; but four kings and the Prince of Wales makes a royal flush, and that is unprecedented!”

Buffalo Bill and his troupe pose in front of the Wyoming

The final coach of the Deadwood Stage, ready to depart from Cheyenne’s Inter-Ocean Hotel, 19 February 1887

The End of the Road

One year later in 1887, the railroad finally put the Deadwood Stage out of business. On February 19, a final ceremonial coach was loaded up outside Cheyenne’s Inter-Ocean Hotel. Although the company’s oldest driver, “Uncle John” Nunan was scheduled to take the reins, a night of drunken celebration left him too tender to fulfill his duty. The ribbons were passed to the taciturn and reliable George Lathrop, and the coach rattled off to the Black Hills amidst a cheering crowd. While Buffalo Bill’s beleaguered Concord would continue to thrill audiences until 1915, the days of the Deadwood Stage had finally come to an end.

Well, there are some things a man just can’t run away from.

—The Ringo Kid, Stagecoach

Stagecoach-Related Game Mechanics

In Deadlands 1876, the Deadwood Stage has just been established, and is currently operating amidst the Great Sioux War. As the pace of gold mining in the Black Hills accelerates, plans are in the works for the iron-clad Monitor stagecoaches; but as of 1876, transporting precious cargo is still risky, with Persimmon Bill and Dunc Blackburn actively robbing coaches along the Northern Division. Additionally, the recent spate of Indian attacks has put a damper on casual travel, and the Cheyenne & Black Hills Company has begun hiring mounted escorts north of Fort Laramie. This situation presents a wealth of role-playing opportunities; from long, tense, uncomfortable rides suitable for character-driven discourse, to exciting attacks, chases, and feats of derring-do. The following mechanics are designed to help a Marshal run stagecoach-related encounters and resolve various conflicts. But first, a note on the Savage Worlds Driving skill.

Driving (Agility)

In Deadlands 1876, the Driving skill is applicable to any vehicles hitched to horses, mules, or oxen. These include carts, wagons, carriages, and coaches. The higher the Driving skill, the more animals may be controlled, with the general rule of Driving skill minus 2 = number of animals. Therefore a Driving skill of d4 is required to control a single-horse cart or a two-horse team, a Driving skill of d6 may manage a four-horse team, and a Driving skill of d8 permits the operation of a six-horse team. This skill is useful for freighters, muleskinners, and bullwhackers as well, who often manage wagons by walking alongside their teams. A Driving roll is not required for the normal operation of a vehicle, but may be called for unusual circumstances—fording a river, managing a coach up or down a steep gradient, getting a coach unstuck from mud, controlling spooked horses, racing or reckless driving, and maintaining coolness under combat situations.

Heroics Involving a Moving Coach

The following guidelines assume a stagecoach is moving at maximum speed, about 10-12 miles per hour. If the coach is moving more slowly, the Marshal may reduce damage penalties. All combat taking place on a moving coach suffers a –2 action penalty, but passengers inside the coach are granted +4 cover. A character with the Steady Hands Edge ignores this –2 penalty.

Boarding a Moving Coach, Unmounted

An unmounted character may make an attempt to grab onto a moving coach and board it. This is a very dangerous proposition, and requires an Agility roll vs. Target Number 8. If the roll is failed, the character takes 2d6 DAM. If the roll is successful, the character must make an additional roll of Strength vs. TN-4 in order to hang on. A failure wrenches the character from the coach, causing 2d6 DAM.

Boarding a Moving Coach, Mounted

A character on horseback has a much better chance of boarding a moving coach. First, the character must make a serial Riding roll vs. TN-6 in order to line up with the coach. Then, the invader must make an Agility roll vs. TN-4 in order to grab onto the coach and pull herself from her horse. A failure results in the rider falling from her horse and suffering 3d6 DAM.

Being Flung from a Moving Coach

A character who is unwillingly thrown from a moving coach has a single opportunity to grab onto the side and prevent himself from falling off. This requires an Agility roll vs. TN-8. Failure to make this roll results in a violent impact with the ground, causing 3d6 DAM. The Marshal may add additional damage depending on the type of terrain. In the case of Incapacitation or Death, the Marshal may rule that the character has fallen under the wheels of the coach or has become trampled by the horses

Jumping from a Moving Coach

A character who plans to deliberately jump from a moving coach is better able to prepare herself for impact. She must make an Agility roll vs. TN-6. A success allows the jumper to make a free Soak roll to absorb the 2d6 DAM incurred upon landing. The Marshal may add additional damage depending on the type of terrain and the starting position of the jump.

Jumping Onto a Horse

Every movie Western featuring an attack on a stagecoach eventually has a character jumping onto the back of a horse hitched to the coach. If this is done from a mounted position, the above rules for “Boarding a Moving Coach” apply, but the Target Number of the Agility roll is raised to TN-8. All damage penalties for failure are increased to 6d6 to represent the possibility of being trampled by horses or drawn under the wheels of the coach. If the driver or passenger attempts to board a horse, the Target roll remains TN-6.

Freeing a Horse

Once a character successfully jumps onto a horse, she may free it by unshackling or cutting through the traces, reins, and related support components. This requires three successful Riding rolls vs. TN-6, which means it requires at least three action rounds. A raise earns a +2 on the next roll. Once a horse is unharnessed, it requires a Riding roll vs. TN-6 to maintain control of the horse, otherwise it breaks free and escapes! If a horse is unhitched from the team, the driver must make a Driving roll vs. TN-6 or lose control of the coach, which has its speed diminished by half. A Critical Failure results in the coach flipping over, inflicting 3d6 DAM on all passengers.

Finding Oneself Underneath a Moving Coach

For the ultimate in heroics, a character may find himself clinging to the undercarriage of a racing coach! Getting there requires a Climbing roll vs. TN-6; a Critical Failure results in falling to the ground and suffering 3d6 DAM. If the Climbing roll is successful, a character may move under the coach by making an Agility roll vs. TN-6. Failure results in a slip for 1d6 DAM and necessitates a Strength roll vs. TN-6 to hang on. A Critical Failure on the Agility roll, or a normal failure on this Strength roll results in a fall, which brings the always-enjoyable 3d6 DAM. To climb up the sides of the coach, another Climbing roll vs. TN-6 must be made, with the same penalties for failure as above. If the character wishes to perform some other task, such as securing dynamite under the coach or hacking through the whippletree with a tomahawk, the Marshal should increase the Target Number of all relevant actions by 4!

Personalities

Marshals wishing to use a stagecoach in their game may need relevant non-player characters. The following statistics may be used as NPC templates for an experienced driver, a capable shotgun messenger, and a professional road agent. If the Marshal wishes these figures to be Extras, he can strike their Edges and lower a few skill ratings. If he’d like to transform them into Wild Cards, he may boost their stats and adds a few additional Edges. If a Marshal would like to research actual historical personages, a list of historical (and fictional!) names follows each profile.

And the watchman told, saying, He came even unto them, and cometh not again: and the driving is like the driving of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he driveth furiously. And Joram said, Make ready. And his chariot was made ready. And Joram king of Israel and Ahaziah king of Judah went out, each in his chariot, and they went out against Jehu, and met him in the portion of Naboth the Jezreelite. And it came to pass, when Joram saw Jehu, that he said, Is it peace, Jehu? And he answered, What peace, so long as the whoredoms of thy mother Jezebel and her witchcrafts are so many?

—2 Kings 9:20-22

Statistics

AGL d8, SMT d6, SPT d6, STR d10, VIG d10, PAR 6, TGH 7. Wounds 3/I. Hindrances: Cautious, Overconfident, or Quirk. Edges: Beast Bond, Professional (Driver), Steady Hands. Skills: Climbing d6, Driving d12+1, Fighting d8, Gambling d6, Notice d8, Pioneering d6, Repair d6, Riding d8, Shooting d8, Survival d6, Taunt d6, Throwing d6. Attack: Model 1873 Winchester carbine, Cal .44-40, RoF 1, DAM 2d6; Coach gun, 12-Gauge, RoF 1, DAM 1-3d6; Colt 1873 SAA revolver, Cal .45, Cap 6, RoF 1, DAM 2d8; Whip, DAM 1d6+d8 AGL.

Description

Sometimes known as a “jehu,” a stagecoach driver is accustomed to long hours and arduous conditions. The Deadwood Stage is justly lauded for hiring superior drivers, good-humored professionals who treat their horses with respect and avoid excess “chin music.” The driver sits in the front box or “boot,” and is forbidden to drink, swear, or enter the coach during inclement weather. Deadwood drivers customarily wear fringed, buckskin gauntlets and buffalo overcoats held tight with a wide, three-buckle belt. Many favor Stetson hats in summer and Scottish caps in winter, and all know the feel of rain, hail, snow, the blazing sun, and biting gnats.

One of the most famous drivers of the Deadwood Stage was Johnny Slaughter, the son of “Judge” John Slaughter, the city marshal of Cheyenne. A friendly and popular driver, in 1877 Slaughter was murdered by the road agent Robert McKimie in a botched hold-up. Other famous drivers of the Deadwood Stage include “Owl-Eyed Tom” Cooper, said to be the “best six-horse stage driver in the United States”; Tom Duffy, who later drove the coach in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, John “Swift Man” Higby, known for his recklessly fast runs; “Uncle John” Bugler Nunan, the oldest driver to handle the ribbons, and George Lathrop, an associate of Luke Voorhees and later author of Memoirs of a Pioneer, entrusted with the final run of the Deadwood Stage in 1887. Famous cinematic jehus include Buck from Stagecoach, whose general competence is masked by his irrepressible fondness for offbeat conversation; Rattlesnake, the perpetually dyspeptic driver from Calamity Jane; and “Six-Horse” Judy from The Hateful Eight, named because she’s “the only Judy you’ve ever seen can drive a six-horse team.”

No wise man ever took a handgun to a gun fight.

—Wyatt Earp

Statistics

AGL d8, SMT d6, SPT d8, STR d6, VIG d8, PAR 7, TGH 6. Wounds 3/I. Hindrance: Code of Honor. Edges: Alertness, Danger Sense, Steady Hands. Skills: Climbing d6, Driving d4, Fighting d10, Intimidation d8, Investigation d6, Notice d10, Repair d4, Riding d8, Shooting d10, Stealth d4, Streetwise d6, Survival d8, Tracking d6. Attack: Double-barreled shotgun, 12-Gauge, RoF 1-2, DAM 1-3d6; Colt 1873 SAA revolver, Cal .45, Cap 6, RoF 1, DAM 2d8.

Description

A shotgun messenger is an armed guard hired to protect a stagecoach’s passengers and cargo. While he commonly rides in the box alongside the driver, he may also be concealed inside the coach or strapped to the rear boot. The best-known shotgun messenger of the Deadwood Stage was Daniel Boone May, “the fastest gun in the Dakotas,” once described by Ambrose Bierce as possessing the “quickest movement that I had ever seen in anything but a cat.” Other Deadwood messengers include Jesse Brown, John Cochran, Scott “Quick Shot” Davis, John Denny, Charley Hayes, Galen E. Hill, William Rafferty, Robert McReynolds, Bob Paul, Billy Simple, C.A. Skinner (killed by road agents in 1877), and Captain A.M. Willard, one of Seth Bullock’s Deadwood deputies. Wyatt and Morgan Earp also famously served as a shotgun messengers.

Andy Devine and George Bancroft as Buck and Marshal “Curley” Wilcox from Stagecoach

Well, I guess you can’t break out of prison and into society in the same week.

—Ringo Kid, Stagecoach

Statistics

AGL d8, SMT d6, SPT d6, STR d10, VIG d8, PAR 7, TGH 7. Wounds 3/I. Hindrance: Wanted. Edges: Followers, Thief. Skills: Climbing d6+2, Demolitions d6, Driving d4, Fighting d10, Gambling d8, Intimidation d10, Lockpicking d8+2, Notice d6, Riding d8, Shooting d10, Stealth d6+2, Streetwise d10, Survival d10, Taunt d6, Tracking d6. Attack: Repeating rifle, Cal .44, RoF 1, DAM 2d6; Colt 1873 SAA revolver, Cal .45, Cap 6, RoF 1, DAM 2d8.

Description

The average road agent is a member of a gang, and may be a deserter, a failed miner, or even a disgruntled former employee. Some are professional thieves drawn to the stage routes as a step along the outlaw career path from cattle rustling to train robbery. The leader of an outlaw gang is always a Wild Card, and generally sports a colorful name, a Trademark Weapon, and a suitably nefarious backstory. He may have an extra few Edges, such as No Mercy and Steady Hands, and a superior Shooting Skill. His lieutenants are Face Cards, and his crew are Extras.

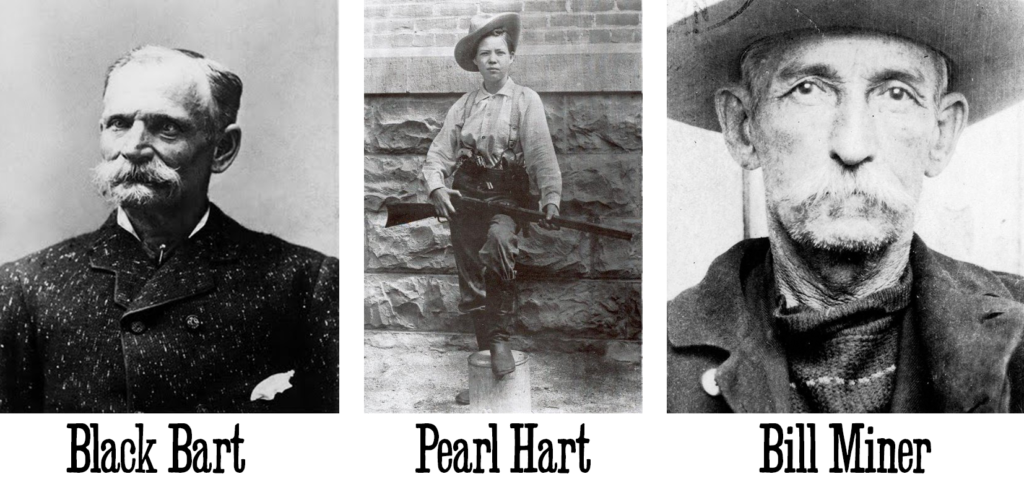

Needless to say, any outlaw worth his salt has robbed a few stagecoaches, including Sam Bass, William Collins, Jesse and Frank James, and Dutch van der Linde. But a few road agents who plagued the Deadwood Stage in particular include William “Persimmon Bill” Chambers, who murdered E.H. “Stuttering” Brown in 1876; Duncan “Dunc” Blackburn, whose rampant crimes resulted in Seth Bullock losing reelection as sheriff of Deadwood; and Robert “Little Reddie” McKimie, a member of the Collins Gang who murdered Johnny Slaughter. Other famous road agents include Charles “Black Bart” Bolles, who robbed coaches in California and Oregon; Bill “The Gentleman Bandit” Miner, author of numerous polite hold-ups in California and British Columbia, William Brazelton, active in New Mexico and Arizona and pictured above wearing a hood; and Peal Hart, the Canadian “Bandit Queen” who robbed coaches in Arizona.

Sources & Notes

Sources

I consulted several books while writing this piece, the most useful being The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express Routes by Agnes Wright Spring, published in 1948 by the University of Nebraska Press and reprinted by Big Byte Books in 2016. While Spring is not the most organized writer, and her mid-century racial and political biases are painfully evident, she offers a tremendous amount of historical detail, from the names of the artisans who decorated the Concord coaches to anecdotes regarding long-forgotten station agents. My secondary resource was Assault on the Deadwood Stage: Road Agents and Shotgun Messengers by Robert K. DeArment. The anecdote about Buffalo Bill and the Prince of Wales comes from Cody’s own memoir, The Life and Adventures of “Buffalo Bill.” Mark Twain’s Roughing It begins with a colorful description of a ride on a mail coach. The Ambrose Bierce quote about Daniel Boone May is found in “A Sole Survivor” from Bits of Autobiography.

Articles and Web Sites

As usual, I am indebted to Geoff B. Dobson’s terrific Wyoming Tales and Trails. A veritable one-man Wikipedia of Western history, Dobson’s site was also my source for Seymour’s quote from Incidents of a Trip Through the Great Platte Valley. Also helpful were Peter Anthony Adams’ Abbot-Downing Concord Coach Page, Dick Eastman’s Abbot-Downing’s Concord Coaches page, the Equine Heritage Institute’s Virtual Horse Museum, and “Stagecoach Terms and Slang” from the Legends of America’s Stagecoach Page. Gregory Michno’s “Stagecoach Attacks—Roll ‘Em” for HistoryNet has some colorful tales about the perils of overland travel. Some other interesting articles relating to stagecoaches include Paul Hedren’s “Chamber of Horrors: ‘Persimmon Bill’ Chambers” for Wild West magazine, and Kat Eschner’s “The Poetic Tale of Literary Outlaw Black Bart” for Smithsonian.com. And if you want to know the exact details of a Concord coach—and I mean exact—you can recreate one with the help of Bob Crane’s PDF guide to “Modeling the Concord Stage Coach!”

Films & Video

Wells Fargo released a ten-minute video “The Making of a Stagecoach Photo Shoot” that features lovely scenes of a six-horse team in action. The companion clips are even more informative, particularly “Building the Coach” and “Training the Team.” Getty Images hosts a wonderful clip of a stagecoach moving at maximum speed. The cheesy-but-fun Arizona Ghostriders host a YouTube segment on “Stagecoaches in the Old West.”

Three feature films that depict dramatic stagecoach rides are John Ford’s 1939 classic Stagecoach, Quentin Tarantino’s “white western” The Hateful Eight, and the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, with “The Mortal Remains” vignette taking place inside a stagecoach interior. There’s also the 1986 “remake” of Stagecoach with Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. (Though, technically, they were more like highwaymen, right?) And of course, I’d be remiss not mentioning Calamity Jane from 1953, featuring Doris Day as mid-century cinema’s most repressed and angry lesbian. I’m not too proud to admit I own this movie on Blu-ray. You have to see her singing “The Deadwood Stage!” Whip-crack-away!

Images

The image in the main banner is lifted from an 1877 illustration depicting eager Hillers departing Cheyenne for Deadwood, and was first published in Leslie’s Illustrated News. The illustration of the coach carrying a bevy of ladies is from a contemporary Harper’s Weekly. The photograph of the Wells Fargo Concord coach comes from Dick Eastman’s site, and was adapted from an article originally published by Wells Fargo. The original photograph with captions may be viewed below. The lovely sepia photo comes from Montana’s Treasure State Lifestyles page. The image of the Wells Fargo six-horse hitch is from a Wells Fargo advertisement. The photograph of a stagecoach holdup is from a 1911 recreation, and has numerous versions across the Internet. The photograph of the “salamander” treasure box is from the Wyoming State Museum. I also used three stills from John Ford’s Stagecoach—Andy Devine as the driver, George Bancroft as shotgun messenger, and the entire cast gathered before the titular stagecoach. The image of the two shotgun messengers is from 1888. The hooded road agent is a photograph of Arizona outlaw William Brazelton. All other photographs and illustrations are in the public domain or were found unattributed.

Author: A. Buell Ruch

Last Modified: 4 July 2019

Email: quail (at) shipwrecklibrary (dot) com

PDF Version: [Coming Soon]